Abstract

Park managers are increasingly faced with responding to the recent rise of those experiencing unsheltered homelessness residing in urban green spaces. In response, researchers have explored and attempted to mitigate a variety of negative social and ecological impacts associated with unsheltered homelessness in urban parks. However, these impacts are often mitigated through the enforcement of policies criminalizing homeless park use or through environmentally harmful changes to landscapes. To help generate more equitable and beneficial solutions to unsheltered homelessness in urban green spaces, this study based in the United States interrogated a variety of stakeholders’ perspectives, including park managers, local community members, and relevant social service organizations. Overall, data expressed how unsheltered homelessness and related cyclical mitigations negatively affected the social and environmental benefits of urban park systems, as well as illuminating the need for a more informed citizenry about the challenges facing individuals experiencing homelessness through public education. Implications for urban park managers and stakeholders are discussed.

Introduction

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates thirty-two per cent of the approximate 549,928 people experiencing homelessness in the United States remain unsheltered (Henry et al., 2016). Many of the unsheltered portions of the homeless population take up residence in public parks. Homelessness has been intertwined with United States parks since the establishment of New York City’s Central Park in 1858 (Whitaker and Browne, 1973). Despite the longstanding presence of individuals experiencing homelessness in parks, the use of public parks by those experiencing homelessness has only recently caught the attention of those responsible for managing urban green spaces. These park managers are usually employees of municipal agencies. Though the origin of growing concern is unknown, the rising costs and hazardous employee conditions related to addressing unsheltered homelessness in parks is a likely contributor (Baur et al., 2015; Braun, 2017). In response to this growing concern, researchers have begun to look at the mitigation strategies used in urban green spaces to reduce the social and environmental impacts associated with homelessness in parks (Bottorff et al., 2012; Baur et al., 2015). We know little however about the effect that proposed mitigations have on the people experiencing homelessness who live in public parks.

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of strategies used by those responsible for urban green spaces to mitigate the complex social and environmental impacts of unsheltered homelessness in parks. We did this by asking what the perceived social and environmental impacts of unsheltered homelessness in parks were, how park managers worked to mitigate those impacts, how mitigation strategies help or hinder the effort to resolve unsheltered homelessness in parks, and how community stakeholders could better work together to address unsheltered homelessness in parks. Hartvigsen et al. (2016) defines an unsheltered person as one who uses public or private spaces void of sleeping accommodations. This study refers to four park stakeholder groups: park managers, who are those responsible for the maintenance of urban green spaces as park managers; housed park users, who are not experiencing homelessness; unhoused park users, who are experiencing homelessness, and park residents, who are experiencing homelessness and residing in parks. Park residents were the primary focus of this study.

In terms of homelessness in parks, the persistent nature of park resident use suggests the unsheltered portion of the homeless population has the greatest impact on parks. A significant amount of literature has documented the negative social and environmental impacts of park residents. Environmental impacts involved damage to the soil, vegetation, and water sources of areas occupied by park residents, while social impacts included housed park user avoidance of areas occupied by park residents due to unpleasant sights, sounds, and smells generated by park residents (Baur et al., 2015; Bottorff et al., 2012; Southard, 1997). The mitigation strategies currently identified by the literature include the use of set campsites, policy and education regarding park use, and collaboration with social service providers (Baur et al., 2015; Borchard, 2009; Egan, 1992; Hodgetts and Stolte, 2015; Klitzing, 2003; Southard, 1997; Spier, 1994). However, attempting to control the negative impacts of park residents can lead to cyclical and extremely costly mitigation strategies (Baur et al., 2015; Southard, 1997). Within a national forest boundary, the United States Forest Service (USFS) spends tens of thousands of dollars repeatedly cleaning and removing trash due to park residents’ simply relocating to other areas of the forest (Baur et al., 2015). Preemptive mitigation strategies aimed at resolving homelessness in parks are largely unimplemented, include collaboration with social service providers, and connect campsites with social service providers (Baur et al., 2015; Bottorff et al., 2012; Egan, 1992). Mitigation strategies that help resolve unsheltered homelessness at large may better address negative social and environmental impacts.

An understanding of park residents may help develop mitigation strategies aimed at resolving unsheltered homelessness. Such mitigations must consider the barriers park residents face in resolving their unsheltered homelessness. The personal, societal, and structural barriers faced by those experiencing homelessness range from mental illness (Perreault et al., 2013) to extreme poverty (Hodgetts et al., 2014), and combine to create a state of homelessness which is difficult to overcome. These difficulties are exacerbated by revanchist state policies that criminalise or further condemn individuals facing homelessness through punitive structures (e.g., DeVerteuil, 2006; Hennigan and Speer, 2018; Mitchell, 2003).

The personal and structural barriers faced by park residents suggest researchers look beyond the social and environmental impacts of park residents. A critical theory approach works to comprehend and dissolve the barriers that power structures render to the resolution of unsheltered homelessness (Kincheloe et al., 2018). Understanding homelessness and considering appropriate mitigations requires a systematic approach that simultaneously addresses the power dynamics of key stakeholders and the potential of environmental inequalities posed by mitigation strategies. Critical theory provides possibilities for environmental justice via social transformation (Giroux, 2003). Social transformation may take the form of public education, park use policy, advocacy, collaborative federal, state, city and non-profit initiatives, and many others. The goal of such social transformation must be inclusive of equitable access of park residents, local (and global) environmental health, and needs of park residents, as well as park managers. The use of critical theory to identify the structural and societal barriers faced by park residents working to resolve homelessness contributes to a clearer picture of the consequential burdens unsheltered homelessness places on public parks. Such insights may identify potential mitigation strategies intended to alleviate the barriers faced by park residents and preclude the subsequent park burdens.

An environmental justice framework (EJF) may encourage new ways of working with park residents (Taylor et al., 2007). Adoption of EJF works to combat environmental inequality by focusing on the “intersection between environmental quality and social hierarchies” (Pellow, 2000: 582). Echoing to work of Egan (1992) and Baur et al. (2015), an EJF calls park managers to work collaboratively with local communities, including park residents and social service providers, to plan for new recreational programming, facilities, and parks that are representative of the recreational and health needs of the whole community (Taylor et al., 2007). An EJF, informed by a critical qualitative exploration with community stakeholders, worked to unearth environmental inequality by questioning social inequity and environmental burdens that resulted from current mitigations.

Urban parks and homelessness

Existing studies have explored the perceived effectiveness of mitigation for homelessness in urban parks, often from a variety of community stakeholder perspectives. Based on qualitative data gathered from park residents, Rose (2015) suggested critical engagement with unsheltered homelessness through political activism may combat the societal and structural inequalities faced by park residents. Displacement of those facing unsheltered homelessness from parks and open spaces is often explained in terms of human and environmental health, regardless if such claims are justified (Rose, 2017). Further, critical qualitative engagement with unsheltered homelessness in parks has demonstrated that park residents’ performances of gender/masculinity (Rose and Johnson, 2017) and their connections with the local environment were both implicated in framing parks as “home” (Rose, 2014). These studies contribute to understanding park resident perceptions of urban green spaces and the form potential societal and structural change may take, but are not inclusive of the potential impact of mitigations on park residents or the perspectives held by other community stakeholders.

Homelessness impacts communities and individuals, and contextualizing these impacts provides a helpful prerequisite to addressing the impacts of homelessness in public parks. Homelessness is incredibly complex and there are many paths into homelessness, including personal, structural, and societal constraints.

On an individual level, trauma, mental illness, substance abuse, and others serve as risk factors for homelessness (Perreault et al., 2013). Structural barriers generate a great deal of stress for those facing the harsh conditions of homelessness, and include poverty, unstable or economically inaccessible housing, unemployment, realities of shelter life, work related problems if employed, displacement, the criminalization of homelessness, and the current state of homeless services (Borchard, 2009; Goodman et al., 1991; Hodgetts et al., 2014; Klitzing, 2003; Milburn and D’Ercole, 1991; Thompson et al., 2006; Thrasher and Mowbray, 1995; Wehman-Brown, 2015). Chronic stress builds as structural barriers combine to discourage the resolution of homelessness, especially among women (Klitzing, 2003). The National Alliance to End Homelessness (2017) found multifaceted structural barriers for those experiencing unsheltered homelessness with unsafe shelter conditions and restrictive assistance rules related to time, gender, pets, sobriety, employment, and faith-based activities. A critical examination of mitigations may identify opportunities to alleviate any contributions to the resolution of unsheltered homelessness among park residents.

Societal barriers take the form of detrimental societal perceptions. Despite the personal and structural barriers faced by those experiencing homelessness Hodgetts and Stolte (2015) reported a public narrative describing homelessness as a choice. Additionally, many housed members of society feel those experiencing homelessness are not part of their community (Wehman-Brown, 2015). Such societal misconceptions of homelessness are especially dangerous for park residents, as Rose (2017) and Bonds and Martin (2016) found those experiencing homelessness were viewed as supposed environmental “contaminants” who require clean up or removal.

A lack of homeless services makes spaces like public parks essential resources and places of refuge for unsheltered people. Casey et al. (2007) found unsheltered women preferred public spaces to institutionalised environments because they were practical, positive spaces in which to live and survive. Those who experience unsheltered homelessness use creativity to avoid contradicting the informal rules of public space by blending in, disguising socially unacceptable activities, limiting belongings, and avoiding peak business hours (Casey et al., 2007; Rose, 2017). These societal barriers reinforce Taylor et al.’s (2007) call for an EJF as a way to critically examine mitigation strategies in an effort to develop park management plans reflective of the health and recreational needs of an entire community.

Addressing personal, structural, and societal barriers in a timely manner is essential to effectively mitigate the impacts of unsheltered homelessness in parks. Southard (1997) found park residents living on rural public parklands could be divided into separatists, voluntary nomadics, and economic refugees. In this typology, separatists lived independently and steered clear of the public eye, while voluntary nomadics lived openly in communities with many vehicle-based homes. Similar to unsheltered women, recently displaced economic refugees preferred the autonomy of public spaces while working to get rehoused (Southard, 1997). Time may be an important factor in the resolution of unsheltered homelessness in public parks. Southard (1997) suggested park resident groups were fluid, and the longer an economic refugee resided in a park, the more likely they were to become a voluntary nomadic. The transition from short to long-term park resident demonstrates the importance of breaking down barriers for recently displaced park residents.

Mitigating the effects of homelessness in parks

A small portion of potential mitigation strategies address the barriers faced by park residents. Egan (1992) suggested a collaborative approach could help park managers address the multifaceted issue of homelessness in parks. Further, Baur et al., (2015) found collaborative partnerships may provide park residents with opportunities to resolve their unsheltered homelessness. Such partnerships could help homeless service providers minimise the barriers associated with unsheltered homelessness and decrease public park dependence among park residents.

Historically, policy creation, implementation, and enforcement have been used to discourage or eliminate unhoused park use and this should be approached with caution (Bonds and Martin, 2016; Taylor et al., 2007). Despite the presence of policy, Baur et al. (2015) found park managers felt their policies were sufficient, and they lacked the staffing needed to enforce policies among unhoused park users. The establishment of camping sites intended for unhoused park users may help concentrate the park resident population and ease connection with social services (Baur et al., 2015). The USFS worked in collaboration with the local community to gather support and funding for a campground designated for those experiencing homelessness residing in Umpqua National Forest, Oregon (Egan, 1992). An exploration of current park policy, policy effectiveness, the park’s capacity to enforce policy, and the impact of policy on park residents helps determine park policy effectiveness and equitability.

Societal barriers to unsheltered homelessness may be counteracted by promoting diversity and inclusion within urban public parks. Young (1990) claimed those who live in urban spaces are more likely to have relationships with people holding different worldviews without demanding conformity. Exposure to diversity may help housed park users build tolerance for park residents (Jacobs, 1961). Kosnoski (2011) applied this acceptance through exposure to public parks, describing parks as spatially mediated spaces to facilitate a culture of tolerance and fluid identities. Public education may help facilitate the transition of parks and open spaces into more mediated public spaces, more tolerant of park residents.

Study purpose and research questions

The purpose of this study was to the examine role of strategies used by park managers in mitigating the complex social and environmental impacts of unsheltered homelessness in parks on the Jordan River Parkway (JRP) in Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. The JRP is a 45-mile long urban riparian trail maintained by a variety of county and city park agencies. In contrast to the dispersed recreational opportunities provided by the vast openness of most urban green spaces, the JRP funnels recreational users to a single trail that runs longitudinally along a narrow riparian corridor. The JRP was selected for the large concentration of park residents, related social and environmental impacts, and mitigation strategies employed by park management. Mitigation strategies were assessed by engaging with key stakeholders, including park management agencies, park residents, and community organizations connected with the JRP. This study examined how unintended structural and societal barriers might be created by well-intentioned mitigation strategies designed to reduce park residents’ social and environmental impacts along the JRP. Further research questions included:

- What do park managers, public service providers, and park residents perceive as the current social and environmental impacts of park residents along the JRP?

- What are park managers doing to mitigate those impacts?

- How do those mitigation strategies help or hinder the effort to resolve unsheltered homelessness along the JRP?

- How might park managers, park residents, and social service providers better work together to address unsheltered homelessness along the JRP?

Methods

This study examined the complexities of mitigating unsheltered homelessness on the JRP using in-depth semi-structured interviews to gather a variety of perspectives from community stakeholders. A qualitative research design supported the exploration of the complex and sensitive nature of the homelessness in parks phenomenon (Creswell, 2015). Findings arose from 19 in-depth semi-structured interviews with park residents, park managers, and social service providers. Participants included five park residents, eight park agency staff, and six local social service providers connected with the JRP.

A convenience sampling method was used to meet the sensitive and nomadic nature of unsheltered homelessness, the limited number JRP-specific park agency staff, and the limited number of local social services employees connected with unsheltered homelessness on the JRP. The researcher volunteered with outreach teams to gain access to park residents on the JRP. In contrast to one-time interviews with park and social service staff, the researcher gradually and continually engaged with park residents to build trust, and subsequently conducted a series of in-depth interviews over a two-month period. Interviews were based on participants’ experiences with unsheltered homelessness on the JRP and ranged from sixteen minutes to two hours. Questions included individual experiences of or with park residents, the perceived social and environmental impacts of park residents, the mitigation strategies used for the impacts identified, and the perceived effectiveness of the mitigation strategies identified. Audio recordings were later transcribed and analyzed.

Findings

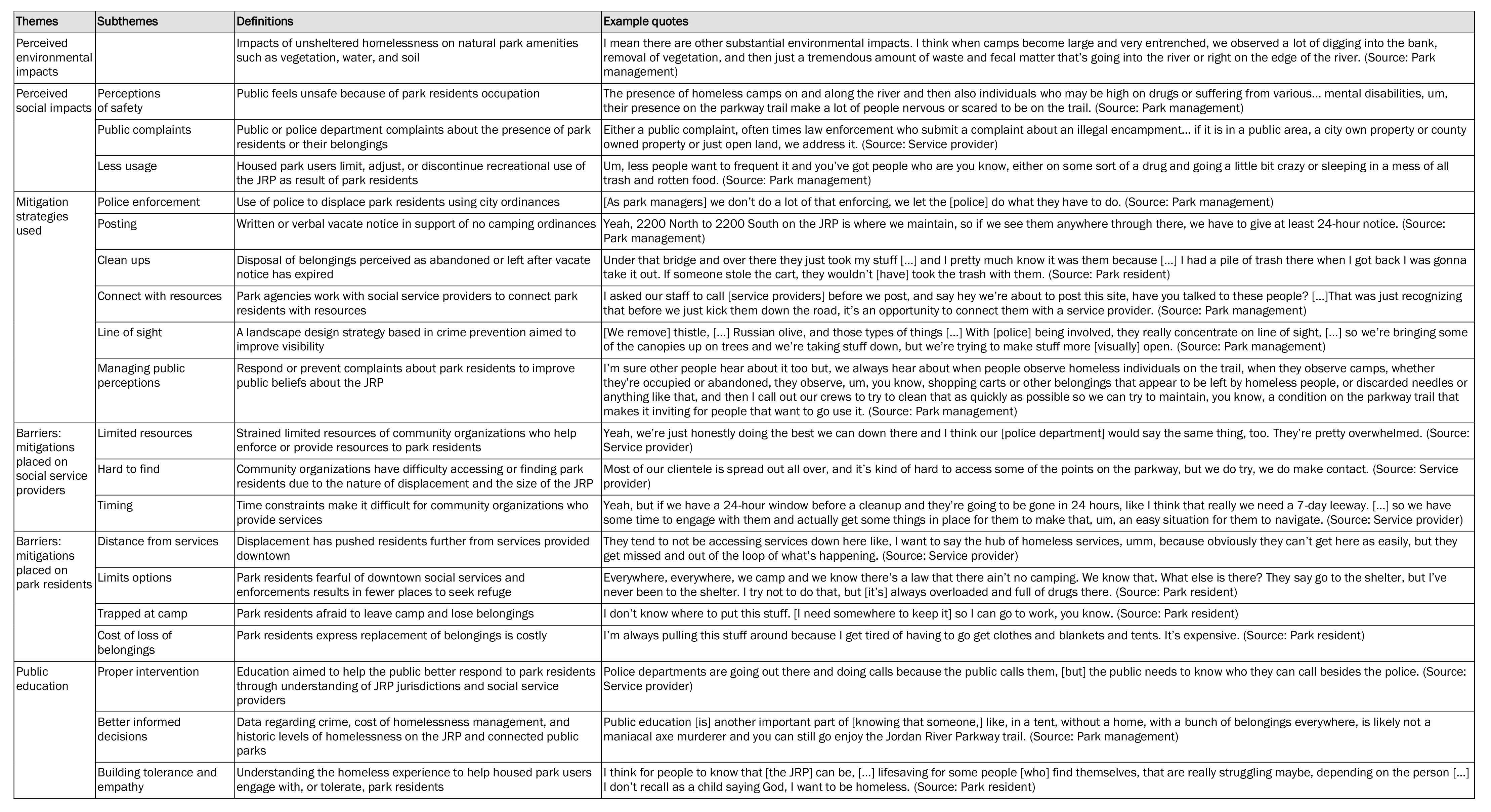

Theme development drew from a hybrid approach of thematic analysis. The hybrid mix combines Boyatzis’s (1998) data-driven inductive approach and Crabtree and Miller’s (1999) deductive a priori template of codes approach. Deductive thematic analysis based on the research questions informed deductive themes of perceived social and environmental impacts of park residents, mitigation strategies used, how identified mitigations hinder the resolution of unsheltered homelessness, and the role of public education in improving collaborative efforts to address unsheltered homelessness. After working with existing a priori themes, additional subthemes were then inductively developed from the data. A codebook (Table 1, below) was developed by combining deductive themes and inductive subthemes. Six dominant themes include perceived environmental impacts, perceived social impacts, mitigation strategies used, barriers mitigations placed social service providers, barriers mitigations placed on park residents, and the opportunity to address unsheltered homelessness in park through public education, while 20 subthemes were developed within the themes. Definitions of the subthemes are also provided, as well as a representative quote extracted from the in-depth semi-structured interview data.

Findings and discussion

Interview data clarified the complex convergence of the social and environmental systems involved in mitigating unsheltered homelessness on the JRP. Critical theory helps unearth the environmental inequality of mitigating unsheltered homelessness. Participants revealed the social and environmental impacts of park residents while park managers described the current strategies used to mitigate the impacts identified. Social services providers and park residents described the negative impact mitigations posed to the resolution of unsheltered homelessness. All participants expressed how a unified need for public education could help community stakeholders’ work to address unsheltered homelessness in parks.

Perceived environmental and social impacts

Unsheltered homelessness resulted in a number of negative social and environmental impacts, supporting previous research (Baur et al., 2015; Southard, 1997). “Waste” was the most significant impact reported by all participants and ranged from litter, such as clothing, furniture, and electronics, to buckets of human faeces. Park managers further explained the waste left along the river corridor presented significant environmental concerns, as decomposing waste could affect the quality of the soil, air, and water.

Park managers further described how the presence of park residents and related waste negatively impacted the social value of JRP. The most evident social reaction came in the form of numerous public complaints to park agencies, health departments, and police departments regarding the occurrence of waste left by park residents. The visible presence of waste, in combination with the reported erratic behavior of park residents, discouraged recreational use, volunteer events, outdoor education classes, and organised canoe or bike rides along the JRP. The public reaction aligns with the public view of park residents outside of a community (Wehman-Brown, 2015) and as environmental contaminants who require clean up or removal (Bonds and Martin, 2016; Rose, 2017). Such public beliefs may bring about negative connotations for the JRP and discourage recreational use by the greater community.

Mitigating negative public perceptions about homelessness greatly concerned park agencies. Frequent patrols and clean ups were used to quickly address, and avoid future, public complaints, again aligning with previous literature suggesting that the public and many agencies view unsheltered homelessness as an environmental contamination (Bonds and Martin, 2016; Rose, 2017). Public requests to remove park infrastructure, such as benches, or vegetation conducive to park residents, were common. Park agency staff showed varying levels of comfort with removal-related mitigation strategies.

Mitigation strategies

A variety of strategies were used to mitigate the negative social and environmental impacts of park residents. In addition to the removal of supposedly problematic vegetation and park infrastructure, park managers collaborated with a number of community organizations to enforce camping ordinances, discard park resident belongings, and placate various public complaints. Park agency staff reported spending up to fifty percent of maintenance time “posting” vacate notices and discarding abandoned park resident belongings. Such mitigations also support the findings of Bonds and Martin (2016) and Rose (2017), and work against the reality of limited housing resources, extreme poverty, and other multi-level barriers park residents face in resolving their unsheltered homelessness.

Park managers stated patrols and the removal of vegetation and park infrastructure were also used to discourage future park resident occupancy. Removal worked to improve visibility and conform to crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED), a technique cited by police and park maintenance staff. Some park agencies used volunteer labor and off-season projects to clear weeds and vegetation that can harbor park residents. A park manager describes:

Well the problem… you eliminate the habitat for [park residents and] they move on, but resources are scarce, and if we pull out the phragmite and the olives and the tamarisks that provide the cover for them. Within five or ten years, it grows back and provides the [park resident] habitat.

Such dehumanizing perceptions of park residents exemplify a belief that those experiencing homelessness are not of the community (Wehman-Brown, 2015). After vegetation was removed, patrols averted the reoccupation of park residents. Activation, or the encouragement of increased housed user park use with a variety of coordinated recreational activities, was also suggested to balance housed and unhoused use but, other than looped trails, the nature of the JRP made it difficult to activate.

Mitigations discouraged the resolution of unsheltered homelessness

Park residents shared that mitigation strategies discouraged the survival of individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness and resolution of unsheltered homelessness. Financial resources of park residents were extremely limited, many living on less than $11 a day, and unable to readily replace belongings. Clean-ups frequently cost park residents belongings needed to survive on the JRP. A park resident described the cost of losing belongings:

We’re like, come on man, let us get our shit. [Police said] you were warned, […] Kenny [had] been off doing whatever downtown. He come back two days later, no camp […] no nothing, no trees. Nothing, he just laid down [and] he froze to death.

Displacement also pushed many park residents further south on the river and away from downtown services. The loss of belongings and fear of displacement also caused worry among park residents and drove many to minimise belongings, and minimise the length of time spent at camp. A park resident explains:

I’m in this bind. Nothing I can do about it, I got to have these blankets and change of clothes, but when I have to get up and move it really ain’t got. [raises voice and paces] I really don’t know too many people around here and people I do, it’s kinda unreal, they got a house, I can’t pull it [shopping cart] into their garage or driveway. […] I don’t know where to put this stuff so I can go to work, you know.

Rose (2017) found similar experiences among urban municipal park residents who avoided leaving belongings unattended after all of their belongings, including identification and cash, had been discarded. Displacement and fear of lost belongings kept many park residents from leaving camp to access social or employment services.

Mitigation strategies also created barriers for social service providers seeking to appease and resolve the harsh conditions of unsheltered homelessness on the JRP. Many police departments, health departments, and social service providers did not have the equipment or workers needed to meet the current demand for enforcement, mitigation, or services related to homelessness. Social service providers with outreach programs had difficulty accessing the JRP, especially during winter months when the paved trail was covered in snow, and struggled to keep up with the frequent relocation of park residents. Additionally, outreach workers stressed that successful service intervention takes time. The limited time and large volume demands of current mitigation strategies kept outreach workers from building the relationships and coordinating the services needed to secure housing or drug rehabilitation for park residents.

A unified call for public education

All participants considered public education as essential to responding to homelessness in parks. Public education was believed to help the public reflect on responses to park residents, foster tolerance, and ease the current demands for mitigation. Specific education suggestions included statistics about crime on the JRP to help diminish the fear of park residents and recreational use. Understanding the multifaceted needs of park residents, related service providers, and park agency approaches to park residents may deter public complaints. For people less familiar with homelessness, the ability to identify organizations responsible for the JRP, the individual needs of park residents, and the availability of social service providers may lessen the number of complaints to police, health, and parks departments. As one park manager explained:

I don’t think that throwing all of our public lands resources into addressing homeless camps is the best approach, not just because it seems like a cyclical problem and it’s not a permanent improvement, I think that by and large people tend to overreact about the impact of homeless camps on our property and a large part comes from a somewhat irrational fear of people who are different because they don’t have a home and I think[…], if we could just be a little more comfortable with the existence of homeless people in our society, we could put money into things that are more positively impactful for everyone.

Such beliefs align with Kosnoski (2011) as parks can act as mediated spaces for urban diversity and acceptance of worldviews outside ourselves. Public education may help the public grow more tolerant, and accepting, of park residents.

Conclusions

This study examined the effects of strategies used to mitigate the perceived environmental and social impacts of park residents on the resolution of unsheltered homelessness in parks. To better understand these effects, we critically explored the perceived social and environmental impacts of park residents, the mitigation strategies used, the impact mitigations had on those working to resolve unsheltered homelessness, and the need for future collaboration. Findings from these research questions and implications for park managers point toward a need for more just and equitable engagement with unsheltered homelessness in parks and open spaces.

First, park managers were readily able to identify the social and environmental impacts of park residents. The social and environmental impacts reported aligned with those documented by previous research (Baur et al., 2015; Bottorff et al., 2012; Southard, 1997). Park managers are closely familiar with the social and physical spaces under their jurisdiction, and often notice small and large changes that take place on a daily, weekly, and/or seasonal basis. For these reasons, impacts were clear to them. Simultaneously, park managers felt unable and untrained to appropriately address unsheltered homelessness, and often indicated that engaging with park residents was not their responsibility. Homelessness, then, was seen as having proximal impacts but distal solutions, creating a sense of unease for park managers engaging with unsheltered homelessness. Because of these reasons and likely others, there was a dehumanizing aspect of many park managers’ perspectives of unsheltered homelessness that warrants further analyses and interrogation.

Second, park managers attempted to mitigate various social and environmental impacts of park residents in a number of ways. The bulk of reported mitigations focused on reacting to the immediate negative impacts of homelessness, and failed to address broader conditions concerning unsheltered homelessness that led park residents to live on the JRP. The costly and cyclical aspects of managing the negative impacts of homelessness in parks noted by Baur et al. (2015) may be resultant of mitigations failing to address the unsheltered homelessness of park residents. Further research may expand on whether the feelings of inadequacy and exemption voiced by park management in relation to the resolution of unsheltered homelessness relates to the reactionary nature of current mitigations.

Third, study findings provide additional insights into how current mitigations discourage the resolution of unsheltered homelessness in parks. Park residents and social service providers reported mitigations involving frequent displacement postings and short vacate times to be problematic. The displacement, belonging loss, and strain on limited resources resulted in park residents lengthening stays on the JRP. For this reason, enforcing mitigations based in park use policy do not discourage or eliminate homelessness in parks as previously suggested (Bonds and Martin, 2016; Taylor et al., 2007). Rather, these mitigation strategies counterintuitively seem to contribute to increased dependency on parks for residency, as a single episode of unsheltered homelessness – which might be overcome relatively quickly – is complicated and exacerbated by displacement and loss of possessions. Findings further support Taylor et al. (2007) who suggested working collaboratively with community organizations and members could help develop recreational opportunities reflective of community needs. Future studies documenting the use of limited posting, lengthened vacate times, and coordination with social service providers would aid in further understanding how mitigations may encourage the resolution of unsheltered homelessness.

Fourth, the findings of this study suggest public education may be a collaborative opportunity community stakeholders agree upon. In the case of park residents, social change would likely take the form of a unified public education initiative as a way to address societal influences of environmental inequality and suggestions for mitigation strategies that balance the social hierarchy and environmental quality of the JRP. A persistent public narrative to remove park residents may simply be a concentrated manifestation of the social inequity faced by those experiencing homelessness. A call for public education supports Kosnoski (2011) who suggested parks were spatially mediated spaces that facilitated cultural tolerance. Public education may be the best approach to a highly controversial collision of inequitable social and environmental systems, as it provides park managers with an opportunity to collaborate with social service organizations in an effort to transform costly mitigation strategies into spatial mediation of diversity in urban green spaces. Such actions could foster the inclusion of the unsheltered members of our communities.

Many challenges remain for those interested in thoughtfully and compassionately addressing unsheltered homelessness in parks and open spaces. Challenges for managing urban green spaces include better identifying mitigation strategies that target underlying factors of unsheltered homelessness rather than proximate behaviors. If so, the potential for more lasting interventions is substantially improved. A critical perspective notes that incorporating the social inequity faced by park residents provides a more holistic perspective for park managers seeking to mitigate the effects of unsheltered homelessness. Further, an EJF allows those experiencing unsheltered homelessness and the community organizations tasked with resolving unsheltered homelessness to become part of the resolution of unsheltered homelessness within urban green spaces. A critically inclusive approach could lead urban green spaces all members of the community can come to enjoy.

We would like to thank all those individuals who shared their knowledge and experiences with homelessness on the Jordan River Parkway. Thanks also to research committee members, Dr. Jeff Rose, Dr. Dan Dustin, Dr. Adrienne Cachelin, and Dr. Megha Budruk, for their guidance in undertaking this research.

Milo Neild, 411 N. Central Avenue Suite 750 Arizona State University Phoenix, AZ 85004-2163. Email: mneild@asu.edu

Baur, J., Cerveny, L. and Tynon, J. F. (2015) Homelessness and Long-Term Occupancy in National Forests and Grasslands. Available at: scholarworks.umass.edu [Accessed: 09/10/17]

Bonds, E., and Martin, L. (2016) Treating People Like Pollution: Homelessness and Environmental Injustice. Environmental Justice, 9, 5, 137-141. CrossRef link

Borchard, K. (2009) Between poverty and a lifestyle: The leisure activities of homeless people in Las Vegas. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 39, 4, 441-466. CrossRef link

Bottorff, H., Campi, T., Parcell, S., and Sbragia, S. (2012) Homelessness in the Willamette National Forest: A Qualitative Research Project (Master’s capstone project). Available at: scholarsbank.uoregon.edu [Accessed: 09/10/17]

Boyatzis, R. (1998) Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Braun, C.E. (2017) Hazards of Homeless Encampments and Working in Urban Environments. ASSE Professional Development Conference and Exposition. American Society of Safety Engineers.

Casey, R., Goudie, R. and Reeve, K. (2007) Resistance and identity: homeless women’s use of public spaces. People, Place and Policy Online, 1, 2, 90-97. CrossRef link

Crabtree, B. and Miller, W. (1999) A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In: Crabtree, B. and Miller, W. (ed) Doing qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 163–177.

Creswell, J.W. (2015) Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Boston: Pearson Education.

DeVerteuil, G. (2006) The local state and homeless shelters: Beyond revanchism? Cities, 23, 2, 109-120. CrossRef link

Egan, T. (1992) Shelter for the Rural Homeless: Trees and Sky. The New York Times, [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1992/05/11/us/shelter-for-the-rural-homeless-trees-and-sky.html [Accessed: 06/12/2018]

Giroux, H.A. (2003) Critical theory and educational practice. In: Darder, A., Baltodano, M. and Torres, R.D (eds) The critical pedagogy reader. London: Routledge, 27-56.

Goodman, L., Saxe, L. and Harvey, M. (1991) Homelessness as a psychological trauma: Broadening perspectives. American Psychologist, 46, 11, 1219–1225. CrossRef link

Hartvigsen, A., Frost, P., Coulam, B., Agardy, A., Tolman, A., Gray, A., Sorenson, B., Quackenbush, K., Kohler, T. and Hardy, J. (2016) State of Utah 2016: Comprehensive Report on Homelessness. Salt Lake City: Department of Workforce Services. Available at: utah.gov [Accessed: 11/12/17]

Hennigan, B. and Speer, J. (2018, online first) Compassionate revanchism: The blurry geography of homelessness in the USA. Urban Studies. CrossRef link

Henry, M., Watt, R., Rosenthal, L. and Shivji, A. (2016) The 2016 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Washington DC: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Available at: hudexchange.info [Accessed: 10/14/17]

Hodgetts, D., Stolte, O. and Groot, S. (2014) Towards a relationally and action-orientated social psychology of homelessness. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8, 4, 156–164. CrossRef link

Hodgetts, D. and Stolte, O. (2015) Homeless people’s leisure practices within and beyond urban socio-scapes. Urban Studies, 53, 5. CrossRef link

Jacobs, J. (1961) The death and life of great American cities. New York: Vintage.

Kincheloe, J.L., McLaren, P., Steinberg, S.R. and Monzo, L.D. (2018) Critical Pedagogy and Qualitative Research: Advancing the Bricolage. In: Denzi, N. and Lincoln, Y. (ed) The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 235-260.

Klitzing, S.W. (2003) Coping with chronic stress: Leisure and women who are homeless. Leisure Sciences, 25, 2-3, 163-181. CrossRef link

Kosnoski, J. (2011) Democratic vistas: Frederick Law Olmsted’s parks as spatial mediation of urban diversity. Space and Culture, 14, 1, 51-66. CrossRef link

Manning, R E. and Anderson, L.E. (2012) Managing outdoor recreation: Case studies in the national parks. Wallingford: CABI. CrossRef link

Milburn, N. and D’ercole, A. (1991) Homeless women: Moving toward a comprehensive model. American Psychologist, 46, 11, 1161.

Mitchell, D. (2003) The right to the city: Social justice and the fight for public space. New York: Guilford Press.

National Alliance to End Homelessness (2017) Unsheltered Homelessness: Trends, Causes, and Strategies to Address. Washington DC: National Alliance to End Homelessness. Available at: https://endhomelessness.org [Accessed: 04/15/18]

Pellow, D. (2000) Environmental Inequality Formation. American Behavioral Scientist, 43, 4, 581–601. CrossRef link

Perreault, M., Jaimes, A., Rabouin, D., White, N. D. and Milton, D. (2013) A vacation for the homeless: Evaluating a collaborative community respite programme in Canada through clients’ perspectives. Health & social care in the community, 21, 2, 159-170. CrossRef link

Rose, J. (2014) Ontologies of socioenvironmental justice: Homelessness and the production of social natures. Journal of Leisure Research, 46, 3, 252-271. CrossRef link

Rose, J. (2015) Ethnographic research for social justice: Critical engagement with homelessness in a public park. In: Johnson, C. and Parry, D. (eds.) Fostering social justice through qualitative inquiry: A methodological guide. San Francisco, CA: Left Coast Press, 129-160.

Rose, J. (2017) Cleansing public nature: landscapes of homelessness, health, and displacement. Journal of Political Ecology, 24, 1, 11-23. CrossRef link

Rose, J. and Johnson, C.W. (2017) Homelessness, nature, and health: Toward a feminist political ecology of masculinities. Gender, Place & Culture, 24, 7, 991-1010. CrossRef link

Spier, J.G. (1994) Municipal park usage by the homeless: a policy investigation (Master’s thesis). Available at: scholarworks.sjsu.edu [Accessed 10/12/2017]

Southard, P.A. (1997) Uneasy sanctuary: Homeless campers living on rural public lands. Visual Studies, 12, 2, 47-64. CrossRef link

Stolte, O. and Hodgetts, D. (2015) Being healthy in unhealthy places: Health tactics in a homeless lifeworld. Journal of Health Psychology, 20, 2, 144–153. CrossRef link

Taylor, W.C., Floyd, M.F., Whitt-Glover, M.C. and Brooks, J. (2007) Environmental justice: a framework for collaboration between the public health and parks and recreation fields to study disparities in physical activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 4(s1), S50-S63. CrossRef link

Thompson, S.J., McManus, H., Lantry, J., Windsor, L. and Flynn, P. (2006) Insights from the street: perceptions of services and providers by homeless young adults. Evaluation and Program Planning, 29, 1, 34–43. CrossRef link

Thrasher, S.P. and Mowbray, C.T. (1995) A strengths perspective: An ethnographic study of homeless women with children. Health & social work, 20, 2, 93-101. CrossRef link

Wehman-Brown, G. (2015) Home Is Where You Park: It Place-Making Practices of Car Dwelling in the United States. Space and Culture, 19, 3, 251-259. CrossRef link

Whitaker, B. and Browne, K. (1973) Parks for People. New York: Schocken Books.

Young, I.M. (1990) Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press.