Abstract

Public urban greenspace provides myriad benefits, including health and wellbeing, ‘community cohesion… and local economic growth’ (House of Commons, 2017: 3). As other ‘Third Place’ (Oldenburg, 1989) types, including leisure centres (Conn, 2015), have closed, greenspace’s popularity continues to increase (Heritage Lottery Fund, 2014).

Yet, public sector funding cuts (Stuckler et al, 2017) have forced local authority prioritisation of statutory services (Dickinson and Marson, 2017). Resulting reliance on the voluntary sector is leading to geographical inequalities in greenspace provision (Molin and van den Bosch, 2014). This shift in policy-focus and funding-allocation, and consequent community-responsibilisation for greenspace ‘place-keeping’ (Mathers et al, 2015: 126) means that neglected greenspaces face a ‘vicious circle of decline’ (House of Commons, 2017: 31) and could lead to the production of ‘contested spaces’ (Barker et al, 2017: i).

Whilst the systemic notion of boundary critique (Churchman, 1970; Ulrich, 1996) has been applied within other contexts, this case study seeks to contribute to the literature by applying boundary critique as a methodology for developing a more holistic understanding of greenspace management, and offering solutions to the quandaries faced.

Background

It is widely accepted that quality greenspace provides many benefits (House of Commons, 2017); for example, the promotion of mental well-being (Porcherie et al, 2018) through facilitating concentration and relaxation (World Health Organization, 2016; Branas at al., 2011), and ‘social sustainability’ (Dempsey et al, 2011: 291). Greenspace also supports physical health by encouraging people to exercise, which in turn helps in ‘reducing obesity and improving cardiovascular and respiratory health’ (Branas et al, 2011: 1296). In terms of the financial benefits generated, a recent report notes how London’s public parks alone ‘have a gross asset value in excess of £91 billion’ (Vivid Economics, 2017: 3). Such fiscal values result from greenspaces’ ability to:

improve an area’s attractiveness, increase property values, encourage local investment, generate local business revenue, create and safeguard jobs, enable volunteering, learning and development, and protect homes and businesses from flood risk (The Land Trust, 2018: 3).

Yet, despite such multitudinous advantages, there is a negative correlation between greenspace’s rising popularity (Natural England, 2015) and the dwindling funding underpinning it (House of Commons, 2017; Association for Public Service Excellence, 2017; Greenspace Scotland, 2018). As predicted (Heritage Lottery Fund, 2014), such fiscal reductions have resulted in a loss of staff and skills, reduced maintenance and a resulting decline in quality, and geographical inequity (Heritage Lottery Fund, 2016; Glaister, 2016; GreenSpace Scotland, 2018). As greenspace provision becomes a ‘Cinderella service’ (National Audit Office, 2006: 1), there are also concerns about environmental justice (Wolch et al, 2014; Jennings et al, 2017). Such challenges can be exacerbated by the conflicting goals and values of greenspace stakeholders. A recent consultation noted how:

the demands of sectional interests… often define themselves against other park user interests—e.g. parents of young children versus dog walkers, sports enthusiasts versus quiet recreational users, cyclists versus pedestrians on the footpath network, residents of neighbouring streets who value beauty and tranquillity versus users from further afield attending sports events or community festivals (Parliament.UK, 2017, para 41).

This multi-faceted backdrop indicates the manifestation of an increasingly complex conundrum for those involved with greenspace management. This paper proposes that any sustainable, long-term solution may require the development of a thorough, more holistic understanding of the problems posed to identify potential solutions. It explores whether the application of the systemic notion of boundary critique as a methodology could generate such a comprehensive appreciation of greenspace management through identifying key stakeholder groups, capturing their perceptions through a range of participant-led activities, and involving participants in a ‘member-check process’ (Thomas, 2017: 23). Whilst there is no consensus over what constitutes greenspace, this paper adopts the approach taken by Lee et al. referring to ‘greenspace’ as a ‘park in an urban setting’ (2015: 132).

Despite numerous calls to address the various issues posed to greenspace management, for example through the development of different funding models and the imposition of statutory obligations, (The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, 2006; Topping and Taylor, 2016; Open Spaces Society, 2017; Dickinson, Bennett and Marson (2018)), the Government has yet to take action. This study considers whether such reluctance may stem from the array of stakeholder groups involved with greenspace (Azadi et al., 2011), their differing needs and the resulting potential for inter-group conflict (House of Commons, 2017).

Different stakeholder groups seek to use greenspace in different ways. This can exacerbate the problems already presented by depleted local authority budgets (Association for Public Service Excellence, 2017), particularly in deprived areas (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2015), and lead to the production of ‘contested spaces’ (Barker et al., 2017: i). ‘Multi-stakeholder involvement’ (Azadi et al., 2011) also presents potential issues for ‘green space governance’ (Rosol, 2010). Potentially differing agendas can be aggravated by pressures on local authorities to demonstrate overall value at a time when public finances are already challenged (Local Government Association, 2014), and there is increased demand for housing and workplaces within the urban environment (Centre for Cities, 2015).

Against such a backdrop, this paper explores whether greenspaces could be viewed ‘as if’ they are systems (Stacey, 2011) through: the identification of different stakeholder groups involved in managing greenspaces; an exploration of their perceptions of both the value and importance of greenspace, and the challenges faced by greenspace management; and the consideration of any inter-group accords or tensions and the potential rationale for them. The consideration of greenspaces through such a systemic lens facilitates an opportunity for investigating the potential for boundary critique to be applied as a methodology for: altering stakeholders’ perceptions of what is pertinent; unifying their ideas about greenspaces’ purpose (Ulrich, 1996; Midgley and Pinzon, 2011); and encouraging a more holistic understanding about the challenges faced and potential solutions. Whilst boundary critique has been applied within other settings, for example the development of housing services for older people (Midgley et al., 1997) and conflict prevention (Midgley and Pinzon, 2011), this paper contributes to the existing literature by evaluating the application of boundary critique as a methodology within the context of greenspace management.

The authors believed that this methodology may be appropriate for a number of reasons; namely, because the quandaries faced by stakeholders involved in greenspace management are complex (Bannon, 1972); previous strategies have failed (House of Commons, 2017); there can be inadequacies in the supporting datasets available (Feltynowski et al., 2018); and conflicts in decision-making may have to rely upon political judgement for resolution (Rittel and Webber, 1973). In terms of systems thinking, such strands can be classified together as ‘wicked problems’ (Rittel and Webber, 1973: 155). Following Churchman’s argument that ‘whoever attempts to tame part of a wicked problem, but not the whole, is morally wrong’ (1967: 142), this paper applies boundary critique as a methodology for the development of a more complete understanding of the quandaries facing greenspace management and potential solutions. Such comprehensiveness could facilitate more effective, mutually acceptable decision-making by creating ‘synergies between the environmental, economic, social and governance factors involved’ (Glasson and Cozens, 2010: 25).

Greenspaces as systems

In this context, greenspaces can be considered as systems which: have a purpose (Churchman, 1968), are bounded in time and space, interact with a wider environment and have a boundary (see also Flood, 2010; Stacey, 2011; Midgley, 2000; Ulrich, 2012; Easterby-Smith and Lyles, 2011; Senge, 1990). Central to this concept is the idea of emergence which, in the context of greenspace, could happen when the consideration of the inter-related components of greenspace as a whole results in a number of revelations (Ulrich, 2012). Such components may arise from the diversity of greenspace stakeholders and their motivations and needs. This paper explores whether a particular element of systems thinking, boundary critique (Ulrich, 1996; Midgley and Pinzon, 2011), could be applied as a methodology to facilitate a more holistic understanding of greenspace stakeholders’ contested drivers and desires. Such foundational understanding could help to improve decision-making around the most efficient and effective means for utilising dwindling budgets to sustain the long-term future of greenspace.

As part of this, Ackoff (1979) suggests that managers do not solve problems, they manage messes; problems are dynamic and interrelated, and an optimal solution for an individual element may not be the appropriate solution for the whole mess. In order to address such ‘mess’, Ackoff (1979) argues that systems thinking in challenging reductionism enables a process of defining the system (here, the greenspace); understanding the behaviour within the containing whole (here, the wider environment within which the greenspace exists); and the purpose of that system (here, the purpose of the greenspace). Whilst there is considerable literature on the issues faced by those who manage greenspace, much of it focuses on individual elements, for example income-generation through user-charging schemes, (see for example Dickinson and Marson, 2017). Jansson and Lindgren (2012: 139) argue for a more holistic understanding of greenspace management and recognise the complexity involving different actors, elements and relationships. Mathers et al (2015), in presenting a model of partnership capacity, recognise a range of themes that combine to provide a wider understanding of the nature of a management partnership. Yet this still maintains a single focus, that of partnership capacity, and obtains views from a limited range of voices. This paper adopts boundary critique as a methodology for investigating the management of greenspace as a holistic system; generating an overview of the key components comprised within the greenspace conundrum and exploring any interconnectivity between them as a whole. In capturing the multiple voices, competing definitions and conflicts within a green space system, an appreciation of complexity is achieved through a more holistic understanding.

In practice, there are many distinct approaches to systems thinking arising from conflicting ontological, epistemological, and methodological viewpoints. Drawing upon what is defined as hard systems thinking, Senge (1990) described it as learning to think of the organisation as a system; namely, viewing it as real. Conversely, adopting a soft systems approach, Flood (2010) argues that organisations, such as greenspaces, are social systems that are socially constructed and, as Checkland states (2012: 467), intellectual devices to ’structure debate about possible and desirable change’. This establishes the perspective of viewing an organisation or social structure ‘as if’ it was a system to paint a rich and complex picture, rather than providing the means to an objective view of reality. Midgley (2000) suggests that system boundaries are mental constructs of a personal and social nature that define limits and are perceived as being arbitrary and arguable. The definition of the boundary and the boundary judgement will influence how any problem is viewed, understood and addressed; defining what is pertinent and who may contribute. As such, this paper explores how boundary critique could provide a means of understanding of greenspace as a system of interest (Churchman, 1979).

The systemic idea of boundary critique (Ulrich, 1996) is a method that is used to explore and understand dramatic situations through participative reflective discussion and systemic intervention (Midgley and Pinzon, 2011). Ulrich (1996), Midgley and Pinzon propose a theoretical notion of boundary critique as having implications for conflict prevention, and argue that this concept can explain:

the link between people’s value judgements (about what purpose it is right to pursue) and boundary judgements (what they see as relevant to those purposes).

how situations involving people who make different value and boundary judgements can result in entrenched conflict.

how people can reframe their understandings of the conflict thereby making progress in addressing it by exploring different perspectives on their boundaries of concern (2011: 1543).

Considering greenspaces within a system boundary would enable stakeholder participants to ‘structure a debate about possible and desirable change’ (Checkland, 2012: 468) and ‘define the limit of knowledge that is regarded as pertinent’ (Midgley and Pinzon, 2011: 1545). This empowers both systematic critical evaluation (Ulrich, 2012) and rigorous self-reflection to constantly challenge stakeholder participants’ assumptions (Churchman, 1970).

The application of systems thinking through boundary critique to greenspace management requires all stakeholder participants to be ‘swept in’ (Ulrich, 2012, 1310) to the process to help generate a completeness of understanding. Yet, attempts to ensure such wholeness are contradictory as they require a boundary to be drawn to determine which stakeholder participants are either included in, or excluded from, the process. Therefore, the ‘sweep in’ can never capture the entire system; there is a bounded nature creating a partiality. Recognising such issues, ‘sweep in’ becomes the process of unfolding the necessary boundary judgements (Reynolds, 2004). Such a view acknowledges both the political and power aspects within the decision-making process that emerge from choices taken over who should and who should not be included within the system, but also from the perceptions of the various stakeholder groups. This paper explores whether systemic thinking around the notion of boundary critique has methodological implications for understanding greenspaces. Boundary critique implies a social constructionist methodology (Stacey, 2011) and therefore a method that could capture the multiple voices of stakeholder participants within the defined system of greenspace.

This paper explores whether boundary critique could be applied as a methodology through encouraging participant-led, reflective discussion to capture a range of stakeholders’ perceptions about the issues facing greenspace management. The research aims to utilise this systemic lens to identify any interconnections between these component issues to help generate a more holistic understanding of the management of greenspace as a social system. This paper seeks to utilise such boundary critique to answer the following three research questions. First, what are the key issues which confront greenspace management? Secondly, to what extent is boundary critique beneficial as a methodology for application within the context of greenspace management? Finally, how do the findings generated from such an application of boundary critique develop stakeholders’ understanding with a view to improving decision-making around greenspace management?

Methodology

The aim of the research is to explore the applicability of the systemic idea of boundary critique as a methodology to aid understanding of a particular greenspace site. The research adopted a case study approach of working with a defined greenspace site to generate the depth of understanding needed (Yin, 2018). Viewing the greenspace ‘as if’ a social system implies a subjective epistemology arising from the view of a social constructed social world which led the researchers to adopt an inductive methodology.

The researchers sought guidance from a local authority in the identification of the greenspace site; the only requirements being that it was situated within Yorkshire, and that it had been causing its stakeholders some concern. In response, the local authority identified a park site which comprised over 10 hectares, and included: play areas, sports pitches, open grassland, and heavily-wooded embankments. It was situated in a built-up area on the outskirts of a city, and had been identified by the local authority as a priority site for the injection of funding.

The researchers adopted the principles of boundary critique (Ulrich, 2012) as a methodology to generate data which would provide them with a holistic understanding of the contested quandaries (Midgley and Pinzon, 2011) facing the management of the greenspace and offer new ways of thinking about potential solutions. Snow-ball sampling techniques (Biernacki and Waldorf, 1981) were used to identify 10 participants from a spectrum of different stakeholder groups who were broadly involved in the management of the greenspace. These groups included: the local authority (both officers and managers), the police, volunteers and event organisers.

The researchers conducted in-person, semi-structured interviews with the participants, designing-in boundary critique methodology by including a range of different, participant-led activities. These activities challenged participants to explore their understanding of: the site, its purpose, its challenges and potential solutions. First, drawing on photo-elicitation techniques (Harper, 2002), each of the participants was invited to bring with them five photographs depicting issues which they believed were faced by or within greenspace generally. One participant indicated that they would prefer to participate in a walking interview (Jones et al., 2008) instead, identifying aspects that they would have photographed on the way. During the interviews, participants were asked to: explain the photographs, describe the issues that they identified and discuss why these issues were important to them. The researchers used the photographs to facilitate an open, challenging and reflective conversation about the greenspace. This activity was participant-led, with the interviewer providing prompts to ensure understanding.

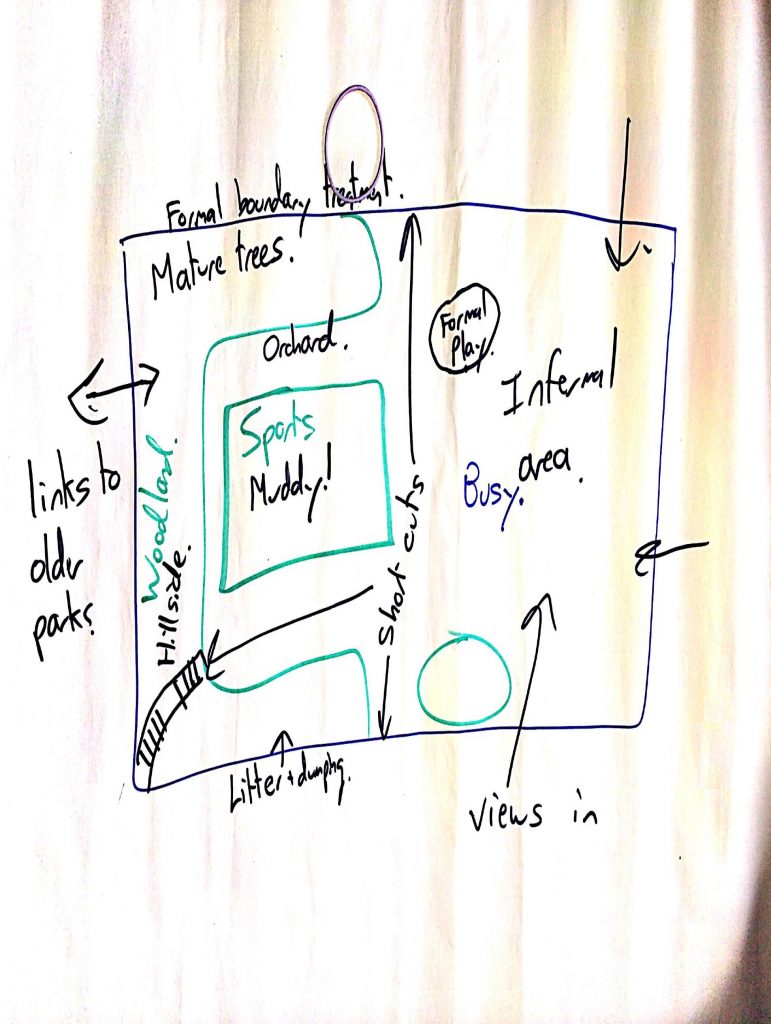

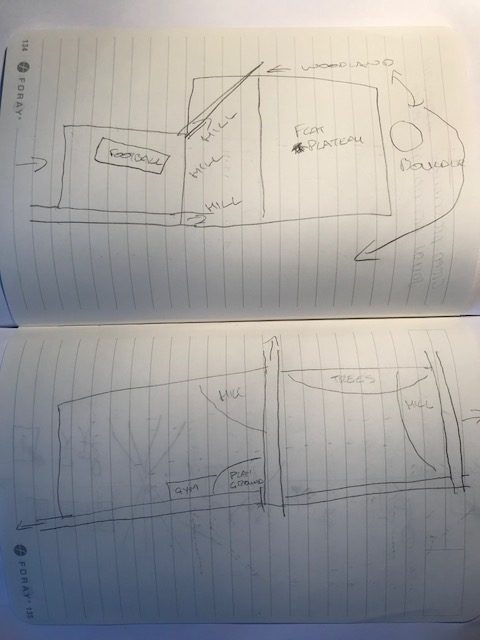

Secondly, during the interviews, each participant was asked to draw a map of the site to facilitate a ‘rich picture’ (Checkland, 1975: 281) (see for example Figure 1). The literature indicates how rich pictures can be used as a means of expressing understanding, and encouraging creative thinking, as participants can communicate more fully through the use of impressions and symbols rather than be limited by the use of words alone (see for example, Wheeldon and Faubert, 2009). From previous experience, the researchers have found that imagery captures the subjective along with fact, and enables the expression of feeling along with the physical reality. Through this second participant-driven activity, the participants were each asked to explain their pictures; providing a running commentary as to what they were drawing and why, and engaging in an open, reflective conversation of the issues they had raised, their significance and, in many cases, how they might be addressed.

Finally, the researchers also adopted timeline mapping procedure (Kolar et al., 2015) to encourage each participant to lead on a reflective conversation as they talked through a particular issue facing the site. These discussions covered the actions that were taken (or not) to resolve the issue and how the participant felt at each point of the process, in order to understand the challenges presented by the mechanisms involved in operating and managing the site (see for example Figure 2).

Each interview took between 45 and 60 minutes to complete and was digitally recorded and transcribed. The researchers thematically coded the transcriptions (Nowell et al., 2017), both on an individual basis and through a process of ‘debriefing’ (Given, 2008: 200) to discuss the ‘rich picture[s]’ (Checkland, 1975: 281) generated for meaning. Mind mapping practice was also used to ‘galvanise’ the data analysis (Burgess-Allen, 2010: 413).

In line with the principles of boundary critique, the researchers also produced a preliminary findings paper and shared it with the participants. They invited participants’ comments as part of a ‘member-check’ process (Thomas, 2017: 23) to assess whether the application of boundary critique as a methodology had developed participants’ understanding of the management issues faced at the site and potential solutions.

Findings

In seeking to identify potential solutions to the quandaries faced by greenspace management, and as discussed in more detail within the methodology section, the researchers adopted a bi-partite approach to the application of boundary critique as a methodology. First, to help identify the interrelated component parts of the greenspace as a system, the researchers conducted interviews, involving a series of participant-led activities, with an array of stakeholder groups involved in greenspace management. Second, to facilitate a holistic consideration of such component parts, the researchers invited further participant input through a member-check process (Thomas, 2017: 23).

Five key themes emerged from the findings. Through the discussion of these findings, the researchers aim to demonstrate the potential for the application of boundary critique as a methodology within the context of greenspace management. The emerging themes were: visibility, communication and perceptions, responsibility and engagement, resourcing, and purpose and identity. Whilst each of these themes will be considered separately, the following discussion also seeks to demonstrate the inextricable links between them in its exploration of the three research questions posed: the identification of the key issues confronting greenspace management, the evaluation of boundary critique as a methodology, and the extent to which its application develops stakeholders’ understanding.

Visibility

This comprised two elements: visibility for site-users and visibility of governance. First, participants believed that visibility into parks was ‘critical to safety… especially in urban parks in poorer parts of town’; describing how a lack of sightlines (see for example Figure 3) had the potential to make parks ‘real no-go zone[s]’ (Council Manager 1) because ‘if other people are using [the site] then people feel safer’ (Council Officer 3). In terms of the site itself, Council Officer 1 suggested that ‘unless you live locally, you don’t know what’s down there’. Whilst participants agreed that increased visibility into the site could dissuade users from engaging in anti-social behaviour, each stakeholder group identified different anti-social behaviours as being particularly problematic. These included: ‘litter, graffiti, bonfires’ (Council Officer 3), ‘fly-tipping… vandalism… off-road bikes, quad bikes, motorbikes’ (Council Manager 2), ‘drug dealing activity’ (Police Officer 1), and ‘graffiti’ (Volunteers 1 and 2). This indicates how the application of boundary critique as a methodology can reveal different participants’ value judgments (about what purpose it is right to pursue) and boundary judgements (about what they perceive as relevant to those purposes). As Midgley and Pinzon (2011: 1543) suggest, such differences in judgements can result in entrenched conflict between stakeholder groups. As this paper will go on to discuss, this indicates how the adoption of a systemic approach could lead to a more complete understanding of the conflicts that may prevent anti-social behaviour being addressed effectively. These findings contributed to suggestions that the current system of greenspace management may compromise stakeholders’ ability to care, which emerged as a recurrent theme throughout the findings.

In terms of governance visibility, Council Officer participants recalled how, before the restructuring, they used to have ‘quite a site presence’ (Council Officer 1); carrying out daily litter-picking, doing risk assessments to inform work programmes, and participating in volunteer group initiatives. Council Officer 2 expressed regret that their ‘all-singing, all-dancing’ role had since ‘fallen by the wayside’. Volunteers similarly lamented that they had ‘lost the [Council’s] dedicated team element’ (Volunteer 1). This similarly reflects Midgley and Pinzon’s research which recognised the link between people’s value judgements and their boundary judgements. These findings illustrate the existence of both frustration and conflict; participants indicated that they knew what is right but felt unable to pursue action that they deemed to be relevant.

Communication and perceptions

The findings indicate the importance of stakeholder perceptions and communications in determining greenspace use and governance. Local authority participants noted public perception, or boundary critique, that greenspaces situated in the south and southwest of the city (which tend to have a wealthier demographic) are prioritised over parks in the north and the northeast leading to conflict between users and officials, when:

the truth is actually that we spend more in the north and northeast of the city, but because of the vandalism and antisocial behaviour we have to take the equipment out, things get burnt, there is broken glass, the paths get churned up and there is quad biking, dog fouling and flytipping, and you do not get that to the southwest to the same degree… it just doesn’t happen (Council Manager 2).

This indicates how the northern and north eastern greenspaces demand more local authority budget, yet the results go unnoticed given that the budget tends to be spent on replacing damaged equipment, rather than upgrading it.

It appears that budget-cuts and consequent restructures fuel such misconceptions. Council officers governing the site reported their inability to manage it as closely as they once did; instead of attending meetings with both neighbourhood action groups and local councillors, they noted how things are ‘more done by emails’ (Council Officer 2). Coupled with their broadening remits, local authority participants reported their incapacity to foster the same levels of communication and trust with other stakeholder groups, leading to a sense of detachment. Related to this, Volunteer 1 also lamented the time it took for decisions to be taken, noting how ‘the process takes so long that the people aren’t there at the end of the process who started it and you’re getting constant replacements’. In a similar vein, Volunteer 2 noted how restructuring has resulted in Council officers changing ‘that many times… you can’t really point a finger and say he was responsible, or not’; all conditions that compromise the ability to care.

The findings suggest that recent media coverage may have exacerbated these issues creating misperceptions and conflict between what is understood to be acceptable and what is required to achieve that, for example greater visibility. Whilst local authority participants acknowledged the benefits of cutting back vegetation to increase visibility, they wondered whether they were ‘brave enough’ (Council Officer 1) because they risked upsetting certain stakeholder groups. Yet none of the participants from the other groups suggested that they would have any objection to such work. This led to the researchers questioning the underpinning rationale for such perceptions and whether the continued media attention may have created a self-perpetuating myth. Relating to this, Midgley and Pinzon (2011: 1543) describe how different value and boundary judgements can result in entrenched conflict and that through the application of boundary critique, people can reframe their understandings and explore their boundaries of concern. This could potentially lead to more effective decision-making, for example about the prioritisation of greenspace management issues and resulting spending.

The findings indicate the Council participants’ recognition that, particularly in the current austere climate, any greenspace action plan needs to take into account local community perceptions. Depending on the scale of the initiative, participants reported utilising a ‘variety of routes’ to seek engagement, including leaflet drops, online consultation, and community meetings (Council Manager 1). They also identified the challenges that reduced staffing caused, particularly the generation of distance between the various stakeholder groups. The findings suggest how the lack of resources had compromised participants’ ability to proactively care for the site, and how local authority restructuring had led to divisions of responsibility and a lack of consistency in understanding of purpose and direction. Participants reported how this disassociation had frustrated the realisation of improvement initiatives; for example, Volunteer 2 noted how a bench ‘wasn’t put where we requested it…. There was a lady who came from the housing with us to take the photos to request where we wanted it, which was half way up the road and it was put very close to one that was already there.’

Drawing these points together, this second theme of communication and perceptions suggests that if local authority officers are unable to consult as widely or deeply as they would like, they will be unable to garner a rounded view of challenges faced and any appetite for potential solutions. Secondly, the community may perceive such apparent lack of consultation as indicating insufficient concern which may result in their disengagement.

Responsibility and engagement

In terms of allocating responsibility for greenspace, participants fell short of apportioning blame, recognising the increasingly challenging circumstances within which other stakeholder groups operate. Volunteer 1 noted the importance of volunteering ‘particularly now that the council is not able to do as much’ but also reflected on how this problem was exacerbated by the dwindling numbers of volunteers. Council Manager 1 similarly identified ‘community ownership’ and support networks as being important; noting how having ‘people who really care about sites’ being ‘the eyes and ears’ and ‘there to be on to things, on to the police, on to community support workers or… politicians when things aren’t right’, could lead to greenspace’s transformation.

Participants suggested that the ‘transient’ nature of local residents (Council Officers 1 and 2), and their resulting lack of ties to the site, could play a key role in its demise. Conversely, they recognised how issues could also arise when stakeholder groups take too much interest in their local greenspace. Flagging issues with ‘gang activity’ (Police Officer 1), participants reported how some greenspace-users ‘territorially patch’ parks as if they ‘own’ them, which discourages use by other stakeholder groups (Council Manager 1). Such evidence of conflicting uses provides another example of the value of boundary critique as a methodological approach for exploring how situations, such as greenspace management, which involve multiple stakeholder groups with different value and boundary judgements, can result in entrenched inter-group conflict.

Resourcing

Participants lamented the continued lack of greenspace resources; expressing their frustration at ‘putting new stuff in if it’s not maintained’ to the point that they ‘would rather not put anything in’ at all (Council Officer 2). They suggested that such previous wastages arose from the adoption of a ‘conveyor belt delivery’ system (Council Manager 1). They revealed their recognition of the importance of adopting a more considered, sequencing approach when addressing greenspace management issues; putting in housing and landscaping greenspace first, before investing in play and outdoor gym equipment, which could otherwise be vandalised.

Reflecting the findings above which indicate that diminished resourcing leads to stakeholders’ inabilities to care, the data disclosed evidence of park-users taking action themselves, in one instance creating their own litter bin (Figure 4). Yet, the findings demonstrated how the local authority could not rely on such voluntary action to plug all of the gaps left by dwindling local authority resources, particularly given the ageing populations and diminishing membership of some volunteer groups.

The findings suggest that such issues are heightened by the park’s array of uses. One local authority participant reported previously having capacity to work with the local community to develop children’s play space (Figure 5) and, by doing so, fostering community relations. Reflecting on the conflicted nature of greenspace usage (referred to above), he also regretted how such play spaces can attract other stakeholder groups, such as drug-users, which can make the site dangerous for children playing there in the day.

Participants noted that the transient nature of local park users; how they spend limited periods of time living in the area before moving elsewhere. They suggested that such transiency leads to inadequate commitment to, and engagement with, the site. Such disregard compromises the development of other stakeholder groups’ knowledge around the needs of these users, adversely affecting their ability to care.

This theme similarly identifies: a range of individual components affecting greenspace management, including the unavailability of resources and stakeholder responses. In drawing out the level of interconnections between such component parts, it contributes to the development of a more holistic understanding of the issues facing greenspace management.

Purpose and identity

Participants recalled the important work previously done by different volunteer groups to improve the site, although some relayed concerns about the piecemeal approach taken. They also noted some stakeholders’ enthusiasm to pay for new play equipment but their reluctance to fund the maintenance of it. Both of these insights suggest the need for the generation of a more complete, overall understanding and a joined-up approach to help direct the depleted resources available for the site.

Some participants strongly believed that the site’s identity, purpose and branding needed addressing to encourage users to feel that it was a park. Council Officer 3 disclosed that they could not ‘even sum up what the site was about’. Police Officer 1 suggested that investment of ‘money to create football pitches and things like that’ was needed to give the site ‘more of a purpose other than a green piece of field’. Participants suggested that the site’s lack of purpose had contributed to the disconnected approach taken to improving it which had resulted in crumbling facilities and an inappropriate design, which included split-sited playgrounds and an illogical, disintegrating network of paths (see for example Figure 6).

Finally, as part of this theme, participants agreed that the site requires further resourcing to facilitate change. Yet most of them could not identify what would constitute successful change. This led to the researchers considering whether the site’s lack of clear purpose compromises its stakeholders’ ability to reach decisions on how to enhance the space for its users.

This theme highlights how the application of boundary critique as a methodological approach within this context has revealed the multi-faceted nature of the issues facing greenspace management and the potential interconnectivity between them. The findings demonstrate: stakeholders’ recognition that current approaches to greenspace management are disjointed, stakeholders’ aspirations for change, and a lack of stakeholder consensus around such a strategic and operational vision.

Taking the five themes together, the adoption of this systemic methodological approach has: facilitated a participant-led exploration of the challenges facing greenspace; identified multiple, complex issues (for example around spending strategies, community engagement, and incompatible greenspace usage); and generated a more complete understanding of stakeholders’ frustrations resulting from diverging value and boundary judgements, and the resulting, conflicts that can ensue. As Midgley and Pinzon (2011) suggest, such a holistic understanding could help to resolve these existing conflicts and prevent potential tensions arising in the future.

Checking understanding and closing the loop

As previously noted, and to reflect the principles of boundary critique as a methodology, the authors presented these findings to the participants through a ‘member-check process’ (Thomas, 2017: 23); inviting them to consider the extent to which the findings affected their understanding of the site’s issues and potential solutions. Some of the participants reported that the findings reflected their expectations but noted that there were a number of issues they had not fully appreciated.

First, participants expressed surprise that some stakeholders were concerned about the potential political consequences of the removal of vegetation to create sightlines. Conversely, one local authority participant recalled being ‘approached four or five times’ by local residents to fell more trees to provide them with ‘more light or better views.’

In a similar vein, participants agreed that stakeholder communication was a key issue. Local authority participants reported how they were’ trying very hard… to have an active Twitter and Facebook feed’ (Council Manager 2) and their own parks’ website page to help them engage with the local community on greenspace issues. Yet, participants from the community groups reported a level of disconnect that compromised stakeholders’ ability to care. There was also evidence of disassociation between perceptions of what was needed. Whilst local authority participants were keen to promote greenspaces to encourage their use and upkeep, and ‘advocat[e] for additional resources’, other stakeholder groups suggested how ‘some facilities may only need a clean or a coat of paint… to encourage more usage’.

Participants reported their interest in being provided with a summary of other stakeholder groups’ perceptions and believed that similar findings could also emerge if the study was replicated on other greenspaces across the city. There were suggestions that these findings could be useful for informing future approaches to ‘encouraging use’ and ‘upkeep’ of greenspaces and ‘advocating for additional resources’ to support them.

Evaluation of the application of boundary critique as a methodology within the context of greenspace

In seeking to answer the three research questions posed which concern: the key issues confronting greenspace management, the evaluation of boundary critique as a methodology, and the extent to which its application develops stakeholders’ understanding, the authors recognise that inclusion also implies exclusion (Reynolds, 2004). In doing so, they note the impossibility of ‘sweep[ing] in’ all of the different greenspace stakeholder groups (Churchman, 1967). The authors acknowledge that the paper’s remit of greenspace management meant that they did not speak with those users who engage in anti-social behaviour at the site. Particularly given the levels of participant concern about anti-social behaviour, and their beliefs that it compromised perceptions of safety at the site, future studies could invite the views of those involved in anti-social behaviour to generate a fuller understanding. Whilst the findings from this study indicate how visibility, presence of authority and thoughtful design can improve greenspace, the authors believe that there may be scope for designing-in other strategic elements; for example, education, communication and development of trust between different stakeholders to encourage cohesiveness in approach.

Reflecting on the techniques used to apply boundary critique as a methodology for exploring greenspace, the authors believe that the ‘rich pictures’ (Checkland, 1975: 281) generated from the participant-led activities, namely: photo-elicitation, mapping and timeline exercises, helped to occasion deeper, and more comprehensive conversations, revealing participants’ key concerns and underpinning rationale (Harper, 2002). Yet, they also found that the use of such tools does require some prior training, understanding and confidence in use. In addition, whilst the depth of findings produced can be rewarding, making sense of the myriad data generated takes time. This suggests that the application of boundary critique as a methodology may not necessarily be appropriate for wider use by any greenspace stakeholders who face particular constraints around either time and/or budget, especially given the diminishing resources available within the current austere climate. Yet, the authors propose that there may be scope to adapt the academically robust method required for this paper to make it more accessible for use, for example through dispensing with the costly transcription of interviews.

In terms of next steps, the local authority has confirmed that it will be drawing on funds (generated from agreements entered into under s.106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended), and public health budgets), to make a series of improvements to the site. The aim is to make the site ‘more welcoming, accessible and safer’ and to improve both the paths’ network and facilities for both play and sports. Whilst it is beyond the scope of this paper, the authors are looking to follow the implementation of: the improvements programme, any steps that may be taken to ensure effective communication with all stakeholder groups at key stages of the process, and any changes in actual, or perceived, usage.

Conclusion

The five themes which emerged from the data point to the ‘ability to care’ as a boundary of concern for the site. This was a central, unifying and emergent issue that came to light through this bi-partite application of boundary critique as a methodology. The contribution made through the participant-led interviews and debriefing with an array of stakeholder groups, is demonstrated by the local authority’s participants’ lack of recognition that their own diminished resources compromises other stakeholders’ ability to care. The findings demonstrate how local authority participants’ capacity to care was compromised by factors including: a restructuring of staff teams leading to broader remits and reduced foci; divisions of responsibility and differing awareness of their impact; and reductions in staff capacity, coupled with increasing pressures to demonstrate value. As a consequence, the formal and (perhaps more importantly) informal contact between local authority participants and users was reported as being compromised and this has limited the ability of motivated stakeholders to have their desired levels of impact on greenspace management. The participant-led nature of the activities during the interviews took the conversations in ways which may not have otherwise emerged through more traditional researcher-led interviews where conversations can be more limited by the researcher’s own frame of reference (see, for example, Bourke, 2014).

The application of boundary critique as a systems thinking methodology within the context of greenspace management has indicated how the combination of these elements can contribute to a self-perpetuating situation of ‘fragmented’ local authority service provision (Public Sector Executive, 2016). This can increase opportunities for anti-social behaviour, and lead to greenspaces becoming ‘fuse areas’ (Barr and Pease, 1990: 309) and reaching a ‘tipping point’ (House of Commons, 2017: 4) from which they can descend into a ‘vicious circle of decline’ (House of Commons, 2017: 31). The unwavering focus on cost and resulting community-responsibilisation compromises proactive ‘place keeping’ (Mathers et al., 2015: 126), particularly at sites with transient populations.

The authors’ exploration of greenspace through the application of boundary critique methodology has facilitated opportunities for both ‘individual and collective reflection’ (Säde‐Pirkko, 2005) which revealed stakeholders’ ‘place attachment’ (Kimpton et al., 2014). The ease with which participants were recruited through snowball sampling technique, (Atkinson and Flint, 2004), and the findings generated, suggest that participants really care about the site. Fostering such emotional connection is important to create a ‘sense of place’ (Beidler and Morrison, 2016: 206) and a ‘place-based community’ (Blandy, 2018: 140). Yet, whilst ‘collective perceptions of poor environmental quality… [can] act as a catalyst for socially cohesive activity and interaction’ (Dempsey et al., 2011: 292), the findings suggest that a range of other elements are also needed to safeguard access to quality greenspace (House of Commons, 2017). The reductionist-driven fragmentation acts to prevent such socially-cohesive activity. A boundary critique approach to site-management, which considers the problems facing greenspace management in a holistic way, could involve the creation of additional greenspace networking groups and the rethinking of responsibilities to maintain a more consistent site presence to foster the development of informal relationships between greenspace management and site-users.

Whilst participants have since reported that a proposed improvement programme at the site is progressing, the local authority will need to develop such relationships to facilitate more inclusive, meaningful consultation to ensure that the site meets a clarified purpose which better serves its users’ needs. Nurturing such community engagement should also help to develop more ‘natural surveillance’ (Bogar and Beyer, 2015: 161), and encourage the community to develop their sense of ‘collective efficacy’ (Blandy, 2007: 47; Wen et al, 2006: 2575; Higgins and Hunt, 2016). The study demonstrates how the application of the boundary critique methodology within the context of greenspace management contributes towards a more complete understanding. This could support, as appropriate, the defensibility of such spaces (Newman, 1973) and ‘situationally prevent’ (Clarke and Weisburd, 1994: 165) their decline through anti-social behaviour.

Overall, the findings suggest that the ongoing quandaries faced by managers may mean that the multitudinous benefits provided by greenspaces are in danger of being jeopardised unless steps are taken to facilitate clearer, and more consistent, stakeholder thinking about greenspaces’ purpose and future. When resources are limited, the need to justify value becomes increasingly important. Without a clear understanding of purpose and benchmark of success, the authors question how value can be judged. The holistic approach adopted for this study can facilitate the development of such definitions of purpose and success, and provide a more rounded judgement of the contribution from, and the needs of, such greenspaces. Stakeholder groups need to recognise the benefits of developing a more holistic understanding, and utilise their combined existing passions for greenspace to work together to identify ways of ensuring more effective inter-stakeholder group communication, resource-identification and allocation to support community-responsibilisation.

The application of the systemic method of boundary critique as a methodology has provided a more holistic understanding of the contested boundaries of concern (Midgley and Pinzon, 2011) confronting a greenspace. Whilst this method is resource-intensive and relies on stakeholder engagement, it generates a more complete appreciation that stakeholders value. With adaptation, it may be applicable for the exploration of spaces facing similarly complex quandaries in quests for the identification of potential solutions and more effective decision-making.

The authors would like to thank the Department of Law & Criminology at Sheffield Hallam University for funding this research and Dr James Marson for his helpful suggestions on an earlier version of this article.

Jill Dickinson, Department of Law and Criminology, Heart of the Campus Building, Collegiate Crescent, Sheffield, S10 2BP. Email: jill.dickinson@shu.ac.uk

Ackoff, R.L. (1979) Resurrecting the future of operational research. Journal of the operational research society, 30, 3, 189-199. CrossRef link

Association for Public Service Excellence (2017) Redefining Neighbourhoods: beyond austerity? Available at: http://www.apse.org.uk/apse/assets/File/Neighbourhood%20Services%20(web).pdf [Accessed: 31/05/18].

Atkinson, R. and Flint, J. (2004) Snowball Sampling. In: Lewis-Beck, M. S., Bryman, A., and Futing Liao, T. (eds) The SAGE encyclopedia of social science research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd, 1044-1047.

Azadi, H., Ho, P., Hafni, E., Zarafshani, K. and Witlox, F. (2011) Multi-Stakeholder Involvement and Urban Green Space Performance. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 54, 6, 785-811. CrossRef link

Bannon, J. J. (1972) Problem-Solving in Recreation and Parks. USA: Sagamore Publishing LLC.

Barker, A., Booth, N., Churchill, D. and Crawford, A. (2017) The Future Prospects of Urban Public Parks: findings – informing change. Available at: https://futureofparks.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/26/2017/07/Job-38853 Future-of-Parks-Findings-Report.pdf [Accessed: 01/06/18].

Barr, R. and Pease, K. (1990) Crime Placement, Displacement, and Deflection. Crime and Justice, 12, 277-318. CrossRef link

Beidler, K. J. and Morrison, J. M. (2016) Sense of place: inquiry and application. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 9, 3, 205-215. CrossRef link

Biernacki, P. and Waldorf, D. (1981) Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10, 2, 141-163. CrossRef link

Blandy, S. (2007) Gated communities in England as a response to crime and disorder: context, effectiveness and implications. People, Place and Policy Online, 1, 2, 47-54. CrossRef link

Blandy, S. (2018) Gated communities revisited: defended homes nested in security enclaves. People, Place and Policy, 11, 3, 136-142. CrossRef link

Bogar, S. and Beyer, K. M. (2015) Green Space, Violence, and Crime: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 17, 2, 160-171. CrossRef link

Bourke, B. (2014) Positionality: Reflecting on the Research Process. The Qualitative Report, 19, 33, 1-9.

Branas, C. C., Cheney, R. A., MacDonald, J. M., Tam, V. W., Jackson, T. D. and Ten Have, T. R. (2011) A Difference-in-Differences Analysis of Health, Safety, and Greening Vacant Urban Space. American Journal of Epidemiology, 174, 11, 1296–1306. CrossRef link

Burgess-Allen, J. (2010) Using mind mapping techniques for rapid qualitative data analysis in public participation processes. Health Expectations: an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 13, 4, 406-415. CrossRef link

Centre for Cities (2015) Urban Demographics: why people live where they do. Available at: http://www.centreforcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/15-11-02-Urban-Demographics.pdf [Accessed: 01/06/18].

Checkland, P. (1975) The Development of Systems Thinking by Systems Practice – a methodology from an action research program. Progress in Cybernetics and Systems Research, 2, 278 – 283.

Checkland, P. (2012) Four Conditions for Serious Systems Thinking and Action. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 29, 465-469. CrossRef link

Churchman, C. (1967) Wicked Problems. Management Science, 14, 4, B141-B142.

Churchman, C.W. (1968) The systems approach. New York: Delacourt Press.

Churchman, C.W. (1970) Operations research as a profession. Management Science, 17, 2, 37-53. CrossRef link

Churchman C. W. (1979) The Systems Approach and Its Enemies. Basic Books: New York.

Clarke, R. V. and Weisburd, D. (1994) Diffusion of Crime Control Benefits: Observations on the Reverse of Displacement. In: Clarke, R.V. (ed.) Crime Prevention Studies, 2, New York: Criminal Justice Press.

Conn, D. (2015) Olympic legacy failure: sports centres under assault by thousand council cuts. The Guardian, [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2015/jul/05/olympic-legacy-failure-sports-centres-council-cuts [Accessed: 11/06/18]

Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S. and Brown, C. (2011) The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Defining Urban Social Sustainability. Sustainable Development, 19, 289–300. CrossRef link

Dickinson, J., Bennett, E. and Marson, J. (2018) Challenges Facing Green Space: Is statute the answer? Journal of Place Management and Development. CrossRef link

Dickinson, J. and Marson, J. (2017) Greenspace Governance: Statutory Solutions from Scotland? Statute Law Review, 00, 00, 1–13. CrossRef link

Easterby-Smith, M. and Lyles, M.A. (2011) Handbook of organizational learning and knowledge management. 2nd ed., United States of America: Wiley.

Feltynowski, M., Kronenberg, J., Bergier, T., Kabisch, N., Laszkiewicz, E., Strohbach, M. W. (2018) Challenges of urban green space management in the face of using inadequate data. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 31, April, 56-66. CrossRef link

Flood, R.L. (2010) The relationship of ‘systems thinking’ to action research. Systems Practice Action Research, 23, 269 – 284. CrossRef link

Given, L. M. (2008) The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Vols. 1-0). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. CrossRef link

Glaister, D. (2016) Public parks ‘nightmare’ funding crisis. The Guardian, [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2016/oct/23/public-parks-nightmare-funding-crisis-parliament-inquiry [Accessed: 08/11/18].

Glasson, J. and Cozens, P. (2010) Making communities safer from crime: An undervalued element in impact assessment. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 31, 1, 25-35. CrossRef link

Greenspace Scotland (2018) The Third State of Scotland’s Greenspace Report. Greenspace Scotland. Available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1aQLMu60G5WRi4QKBCuZJ92oT8eM2sxd3/view [Accessed: 08/11/18].

Harper, D. (2002) Talking about pictures: a case for photo-elicitation. Visual Studies, 17, 1, 13-26. CrossRef link

Heritage Lottery Fund (2014) State of UK Public Parks. Heritage Lottery Fund. Available at: https://www.hlf.org.uk/state-uk-public-parks-2014 [Accessed: 08/11/18].

Heritage Lottery Fund (2016) State of UK Public Parks. Heritage Lottery Fund. Available at: https://www.hlf.org.uk/state-uk-public-parks-2016 [Accessed: 08/11/18].

Higgins, B. R. and Hunt, J. (2016) Collective Efficacy: Taking Action to Improve Neighborhoods. National Institute of Justice Journal, 277, 18-21.

House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee (2017) Public Parks: Seventh Report of Session 2016-17. House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmcomloc/45/45.pdf [Accessed: 25/07/17].

Jansson, M. and Lindgren, T.(2012) A review of the concept ‘management’ in relation to urban landscapes and green spaces: Toward a holistic understanding. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 11, 139-145. CrossRef link

Jennings, V., Floyd, M.F., Shanahan, D., Coutts, C. and Sinykin, A. (2017) Emerging issues in urban ecology: implications for research, social justice, human health, and well-being. Population and Environment, 39, 1, 69-86. CrossRef link

Jones, P., Bunce, G., Evans, J., Gibbs, H. and Ricketts Hein, J. (2008) Exploring space and place with walking interviews. Journal of Research Practice, 4, 2, Article D2.

Kimpton, A., Wickes, R. and Corcoran, J. (2014) Greenspace and Place Attachment: Do Greener Suburbs Lead to Greater Residential Place Attachment? Urban Policy and Research, 32, 4, 477-497. CrossRef link

Kolar, K., Ahmad, F., Chan, L. and Erickson, P. (2015) Timeline Mapping in Qualitative Interviews: a study of resilience with marginalized groups. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14, 3, 13-32. CrossRef link

Lee, A. C. K., Jordan, H. C. and Horsley, J. (2015) Value of urban green spaces in promoting healthy living and wellbeing: prospects for planning. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 8, 131–137. CrossRef link

Local Government Association (2014) Under Pressure: How councils are planning for future cuts. Local Government Association. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/under-pressure-how-counci-471.pdf [Accessed: 01/06/18].

Mathers, A., Dempsey, N. and Froik-Molin, J. (2015) Place-keeping in action: Evaluating the capacity of green space partnerships in England. Landscape and Urban Planning, 139, July, 126-136. CrossRef link

Midgley, G. (2000) Systemic Intervention. New York: Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers.

Midgley, G., Munlo, I. and Brown, M. (1997) The theory and practice of boundary critique: developing housing services for older people. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 49, 5, 467-478. CrossRef link

Midgley, G., and Pinzon, L. (2011) Boundary critique and its implications for conflict prevention. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 62, 1543–1554. CrossRef link

Molin, J. F. and van den Bosch, C.C.K. (2014) Between big ideas and daily realities: the roles and perspectives of Danish municipal green space managers on public involvement in green space maintenance. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 13, 553-561. CrossRef link

National Audit Office (2006) Enhancing Urban Green Space. National Audit Office. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2006/03/0506935.pdf [Accessed: 08/11/18].

Natural England (2015) Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment: The national survey on people and the natural environment. Natural England. Available at: http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/6579788732956672?category=47018 [Accessed: 31/05/18].

Newman, O. (1973) People and Design in the Violent City. United States of America: Architectural Press.

Nowell, L. S., Morris, J. M., White, D. E. and Moules, N. J. (2017) Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16, 1–13. CrossRef link

Oldenburg R. (1989) The Great Good Place: cafés, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangout and how they get you through the day. Paragon House: New York.

Open Spaces Society (2017) We call for duty on local authorities to protect parks and green spaces. Available at: https://www.oss.org.uk/we-call-for-duty-on-local-authorities-to-protect-parks-and-green-spaces/ [Accessed: 09/11/18]

Parliament.UK (2017) What challenges are facing the parks sector? Competing demands and tensions between park users. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmcomloc/45/4506.htm [Accessed: 01/06/18].

Porcherie, M., Lejeune, M., Gaudel, M., Pommier, J., Faure, E., Heritage, Z., Rican, S., Simos, J., Cantoreggi, N .L., Roué Le Gall, A., Cambon, L. and Regnaux, J. (2018) Urban green spaces and cancer: a protocol for a scoping review. British Medical Journal Open, 8, e018851. CrossRef link

Public Sector Executive (2016) Public Health Cuts Creating a False Economy and Risk Widening Inequalities. Available at: http://www.publicsectorexecutive.com/Public-Sector-News/public-health-cuts-creating-a-false-economy-and-risk-widening-inequalities [Accessed: 09/06/18].

Reynolds, M. (2004) Churchman and Maturana: Enriching the notion of self-organisation for social design. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 17, 6, 539-555. CrossRef link

Rittel, H. W. J. and Webber, M. M. (1973) Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences, 4, 155-169. CrossRef link

Rosol, M. (2010) Public participation in post-Fordist urban green space governance: the case of community gardens in Berlin. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34, 3, 548-63. CrossRef link

Säde‐Pirkko, N. (2005) Individual and collective reflection: how to meet the needs of development in teaching. European Journal of Teacher Education, 28, 2. 209-219.

Senge, P.M. (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday Currency.

Stacey, R. D. (2011) Strategic management and organisational dynamics: The challenge of complexity. (6th ed). Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Stuckler, S., Reeves, A., Loopstra, R., Karanikolos, M. and McKee, M. (2017) Austerity and Health: the impact in the UK and Europe. European Journal of Public Health, 27, 4, 1827.

The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (2006) Paying for parks: eight models for funding urban green spaces. The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110118111034/http://www.cabe.org.uk/files/paying-for-parks.pdf [Accessed: 08/11/18].

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2015) The cost of cuts: the impact on local government and poorer communities. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Available at: https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/Summary-Final.pdf [Accessed: 01/06/18].

The Land Trust (2018) The Economic Value of our Greenspaces. Available at: https://thelandtrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/The-economic-value-of-our-green-spaces.pdf [Accessed: 31/05/18].

Thomas, D. R. (2017) Feedback from research participants: are member checks useful in qualitative research? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 14, 1, 23-41. CrossRef link

Topping, A. and Taylor, M. (2016) Hundreds of thousands call for legal protection of UK parks. The Guardian, [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/sep/30/hundreds-of-thousands-call-for-legal-protection-of-uk-parks [Accessed: 08/11/18].

Ulrich, W. (1996) Critical Systems Thinking for Citizens: a research proposal. Hull: University of Hull Centre for Systems Studies. CrossRef link

Ulrich, W. (2012) Operational research and critical systems thinking – an integrated perspective of part 1: OR as applied systems thinking. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 63, 1228 – 1247. CrossRef link

Vivid Economics (2017) Natural Capital Accounts for Public Green Space in London. Report prepared for Greater London Authority, National Trust and Heritage Lottery Fund. London.gov. Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/11015viv_natural_capital_account_for_london_v7_full_vis.pdf [Accessed: 31/05/18].

Wen, M., Hawkley, L. C. and Cacioppo, J. T. (2006) Objective and perceived neighborhood environment, individual SES and psychosocial factors, and self-rated health: An analysis of older adults in Cook County, Illinois. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 257–259. CrossRef link

Wheeldon, J. and Faubert, J. (2009) Framing Experience: Concept Maps, Mind Maps, and Data Collection in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8, 3, 68-83. CrossRef link

Wolch, J. R., Byrne, J. and Newell, J. P. (2014) Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landscape and Urban Planning, 125, May, 234-244. CrossRef link

World Health Organization (2016) Urban Green Spaces and Health: a review of evidence. World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/321971/Urban-green-spaces-and-health-review-evidence.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed: 30/05/18].

Yin, R. K. (2018) Case Study Research and Applications: Design and methods. (6th ed). USA: Sage Publications Inc.