Abstract

Issues of sustainable development, liveable cities, green infrastructure, and urban ecosystem services currently receive attention from researchers and decision-makers. Furthermore, the benefits to public wellbeing and health of high quality open spaces and green areas are now undisputed (e.g. Simson, 2008; Booth, 2005, 2006). However, with increasing pressure on urban landscapes for competing uses like housing-development green-spaces are under threat. Furthermore, austerity-driven cuts to local authority budgets mean loss of core services and skills relating to open-space management and planning. Some local authorities such as Newcastle City Council are withdrawing all expenditure on parks and community spaces. With major challenges in providing good quality urban green-spaces, the loss of most local authority countryside management services from 2008 onwards, reflects bigger problems (see Rotherham, 2014, 2015 for example).

Within this wider scenario has been the growing importance of Public Private Partnerships (PPP) to deliver core environmental and green-space services in many urban areas. These have been seen as possible fixes for the current waves of austerity cuts and many local authorities such as Sheffield City Council have gone down this route. Nevertheless, real costs (financial and otherwise) of Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs) are now emerging (Syal, 2018). There are also issues of public access to information once contracts become ‘commercially sensitive’ and of profit-driven delivery of core ‘public benefit’ services. These changes threaten ‘local environmental democracy’ as part of a wider shift in democratic processes (Flinders, 2012, 2017).

This paper examines wider issues of austerity-driven cuts to green-space services, of PFI projects, and of local environmental democracy. It takes the Sheffield street-trees initiative as an exemplar case-study to interrogate the broad concerns.

Introduction

In the context of long-term ‘austerity’ and severe cuts in local authority services, matters such as nature conservation, countryside management, tree and woodland management, and other local environmental services are under stress (e.g. Rotherham 2013, 2015; Johnston, 2017). With services like highways maintenance and tree-care subject to resource cuts and privatisation, central government has advocated devolution of local decision-making and of democratic processes (e.g. Anon., 2010). However, these two drivers of change, (in urban environments especially), produce tensions between communities, local politicians, private sector contractors, and environmental activists.

In this article we bring this situation into sharp focus through a case study of Sheffield’s street-trees. Sheffield’s trees have become a controversial topic of debate and conflict as a result of a largescale tree-removal programme tied to a large highways maintenance PFI project running over 25 years. Although there was already concern for street trees as disputed environmental resources in the UK (Rotherham, 2010a, 2010b) this particular dispute has grown into a globally-recognised environmental campaign focusing on the perceived breakdown of established processes and protocols of green-space and community engagement and ‘ownership’. Sheffield City Council has pressed for custodial sentences for unhappy citizens objecting to tree removal. The conflict has incurred large costs to the local authority and community, with over one million pounds additional expenditure associated with demonstrations, legal processes, and compensation to the private-sector partner (Anon., 2017; Hobson, 2016; Cumber, 2017; Burn, 2018; Done-Johns, 2018).

The Sheffield case-study follows a long period since the late 1970s when Sheffield City Council had a reputation as a leading local authority on both environmental issues and in terms of the positive engagement of local people in woods, trees and countryside management issues (e.g. Anon., 1987a; Anon., 1987b; Anon., 1987c; Anon., 1990; and Bownes et al., 1991). Furthermore, since the 1960s, Sheffield prided itself as the ‘Clean Air City’, having taken radical steps to reduce the gross air pollution of the 1960s and earlier times (Rotherham, 2014, 2018). Additionally, in recent decades the city boasted of its rich heritage of eighty or more ‘ancient woodlands’ (Jones, 2009), and in 1961, former Poet Laureate the late Sir John Betjeman described leafy Broomhill as England’s prettiest suburb; further immortalised in his 1966, poem ‘An Edwardian Sunday’ (Darn, 2018; Sheffield Star, 2009). At the core of the image of Sheffield ‘the green city’ is its remarkable heritage of street trees (Anon.3, 1987). This pride in green heritage, and commitments made by the Council to the community such as its Nature Conservation Strategy (Bownes et al., 1991) in which the street trees are highlighted as the key to forging, strengthening and creating ‘green corridors’, has triggered strong reactions to the mass felling. It is this on-going situation and its wider ramifications that we address in this article.

The core argument of this article is that a paradox exists – ‘the street-tree paradox’. Scientific evidence demonstrates significant societal benefits from urban street-trees (social, economic, environmental, well-being-related, etc.) and yet political (local government reforms) and ‘post-crisis’ financial tools appear to endanger the number and health of street-trees in many cities within and beyond the UK. This article explored the ‘street tree paradox’ and its ecological and political implications.

Research questions

The paper raises a number of questions of which the following are central to our arguments:

- Is there a conflict between evidence of environmental, economic, and social benefits associated with urban street-trees and the directions of national political policies and their local manifestations?

- Can the example of urban street-tree management be taken as a ‘lightning rod’ for wider matters of local, environmental democracy?

- Does the case study as presented suggest fundamental problems in the adoption of PFI projects for delivery of local environmental services?

Methodological approaches

The research involved a mixed-methods approach built upon long-term observational studies of local government countryside services (including an England-wide survey of local authorities) (Rotherham, 2015) and detailed case study of recent events in the English city, Sheffield. The case study combined ethnographic fieldwork with semi-structured interviews (see Flinders and Wood, 2018) plus action research with involved groups and organisations. There were four major public-facing meetings with key experts and stakeholders: 1) ‘Sheffield Street Trees’ – public meeting hosted by the Green Party, October 2013, St Mary’s Community Centre; 2) ‘Action for Woods & Trees’ community event, Friday 15th and Saturday 16th May, St Mary’s Community Centre, Bramall Lane, Sheffield; 3) ‘Action for Woods & Trees – Discovering and Protecting Sheffield’s Woodland Heritage’, Saturday 8th October 2016; 4) ‘The Sheffield Street Trees debacle – an avoidable crisis’, Sheffield Hallam University, Tuesday 6th December, 2017].

Further validation was provided by thirty-year-long ‘action research’ and observation by one of the authors (Rotherham) as a lead officer for Sheffield City Council in the 1980s and 1990s. This role involved formulating and consulting on policies for countryside, ecology, woodlands and trees throughout Sheffield. He was subsequently involved in community-liaison and work with expert advisors to the ‘Sheffield Street Tree’ campaign.

The structure of the paper

Following this introduction, the paper is structured in three further sections: 1) Exploration of the changing political context in which the politics of urban green-space takes place. Its main argument is that combined economic austerity and political reform increase vulnerability of urban street-trees to irrational short-term incentives that overlook their wider value; 2) A case-study of ‘No Stump City’ which we argue, provides an almost perfect microcosm of the empirical manifestation of broader issues and themes discussed earlier. This, we suggest, redefines relationships between people, place, and policy-making in the politics of urban green-space; 3) Having reviewed the case-study, the final section briefly explores the wider implications of tensions raised in the article. This focuses on environmental governance in an age of austerity, the pathologies of public-private partnerships in a social context defined by anti-political sentiment, and finally ‘the politics of co-production’.

The main concluding argument is that the international controversy and discussion provoked by the Sheffield street-trees issue may reflect street-trees emerging as a lightning-rod for far broader social concerns about how we ‘do’ politics, in general, and local environmental politics, specifically. The extreme responses and deep-felt public sentiments in Sheffield may stem from the elimination of local stakeholders and their environmental resources from decision-making processes. This in turn reflects cuts in local governance and publicly-accountable local services.

Part I – Austerity and the politics of urban green space

Urban street-trees are increasingly threatened by long-term under-funding of essential maintenance and harsh cuts to local government services in recent decades (Rotherham, 2015). In urban environments and with climate change impacts, trees are stressed and need on-going care and maintenance. Support delivered by local authorities requires adequate funding and specialist skills (Booth, 2005, 2006). With a climate of budget- and service-cuts, local councils have removed specialist tree-care services, and greatly reduced highway tree maintenance budgets.

It is unsurprising that local government may prefer tree removal to expensive, on-going maintenance. Big, mature trees may present significant insurance risks with on-going professional and legal debates about what may be considered reasonable professional competence for tree condition survey and assessment. For trees on private land adjacent to highways this can become significant; increasingly so with societal culture of blame, litigation, and compensation. For landowners and local authorities with big trees, risks rather than benefits become the focus (Rotherham, 2010b). Whilst in recent years, approaches to risk have become more pragmatic (addressed by nationally-agreed standards), the situation still worries landowners with large highway trees (Rotherham, 2010b). For individual urban householders, big street trees close to buildings can be a serious concern in terms of damage, leaf-fall, shade, and liability (Rotherham, 2010b). Yet large ‘forest trees’ can, with good management, do very well. Furthermore, these big trees provide significant ecosystem services such as climate-change mitigation, flood-proofing, and biodiversity benefits. Smaller trees (ornamental cherries and almonds) also cause serious damage to pavements and other built structures but again are highly valued by local communities (Rotherham, 2010b).

With enforced economic austerity, particularly since the 2008 downturn, local authority funding from UK central government has fallen with impacts of resource reductions highlighted for local authority countryside, woodland, tree management, and associated environmental services (Rotherham, 2015). Rotherham (2010a, 2010b) noted the developing schism between some professionals in the arboricultural industry with responsibilities for highway tree maintenance and those with wider community and environmental perspectives. There are divergent views on ‘whose’ trees these were and ‘who’ should decide their management or removal, as observed by the authors at an international conference ‘Do street trees have a future?’, which included a discussion about street trees (Rotherham, 2010a). At one extreme were professionals considering all aspects of street-tree management to be their sole domain; at the other, were stakeholders suggesting trees belonged to the community. Furthermore, for urban communities, highway trees were hugely important to local environmental quality, biodiversity, heritage, and sense of place (Rotherham, 2010b, 2013, 2015). Rotherham (2010b) provided the first in-depth analysis and breakdown of complex social and planning interactions based around issues of street-tree management. These have since emerged to be tested through growing, locally-based disputes around Britain with street-tree maintenance and replacement contracts passed to private-sector businesses through PFI projects. The Sheffield case is perhaps best-known but only one of many around the country, with further examples to be found in Newcastle, Birmingham and Southampton.

To more fully understand the tensions and disputes it is necessary to explore how local government policies and strategies developed over recent decades, how these engaged local communities and experts, and how key processes have changed through political influences and austerity. These matters are, we assert, central to the Sheffield dispute. A brief overview of these issues follows: see Rotherham (2014; 2015) for more detailed analysis

From the 1960s, through the 1970s, and into the 1980s, concerns rose over environmental issues amid calls for improved local environmental quality and access to better green-spaces. Furthermore, with the emergence of national, regional, and local conservation and environmental NGOs, local activists became increasingly influential in the media, lobbying, and local politics. In cities like Sheffield this was often through the medium of the ruling political group in the Council. The local political structures themselves had strong local democracy and accountability with hierarchies of council committees reporting to the main committee. Every ward member served on at least three committees / sub-committees, each with a chair and deputy chair. The Council Leader appointed by the ruling political party, oversaw the process and was served by paid directors of various City Council Departments. Additional to the above, the ward councillors were involved and engaged in local matters in their individual wards

The system was strong in terms of thorough ‘processes’ of discussion, determination, and accountability to develop and implement strategy and policy. Its weakness was bureaucracy and potential for political influence through interest groups and cliques. However, the system did ensure that city councillors had access to key information and could seek to influence policy decisions and outcomes. Furthermore, the Council Leader and other senior figures had access to professional specialist advisors on matters such as local economic development and environmental issues.

By the 1980s, it was clear to senior local politicians and officers that ‘environment’ and ‘countryside’ (including woods and trees) were issues of importance and political significance. To most effectively address these matters alongside the more-established issues of housing, health, planning, transport and highways, education, and economic development, it was necessary to a) establish internal specialist advisory services, b) set-up specialist and public consultations on strategies and policies with implementation programmes against agreed targets, and c) employ teams of officers to deliver necessary work.

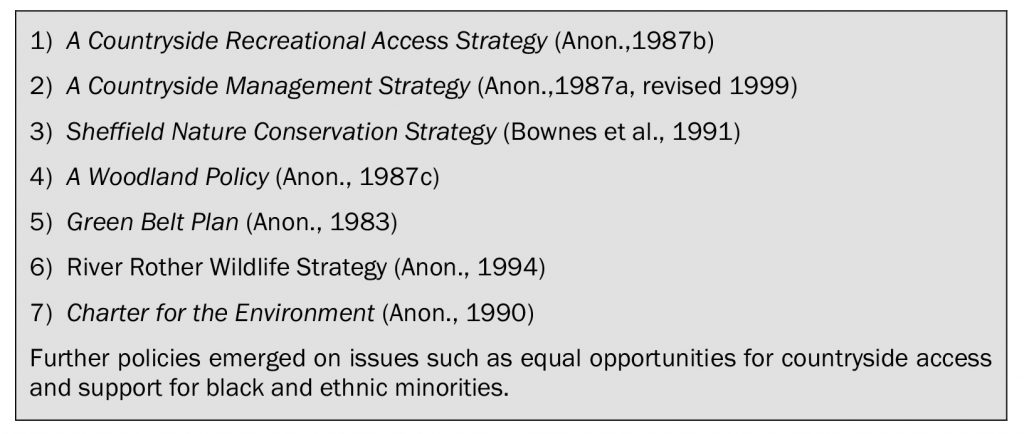

A major driver was the 1960s emergence of the Countryside Commission (Rotherham, 2015) to present local authorities with ideal models for environmental improvement, countryside management, and community involvement (Countryside Commission, 1978, 1979, 1981, 1987). Not only was there guidance on strategy and policy, but there were also central government financial incentives to help local authorities adopt tested models to enhance achievement. An additional stimulus to conservation-related strategies and policies was the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act (Anon., 1981); the first national legislation addressing nature conservation issues holistically. One policy directive that followed the Act was the ‘Planning Policy Guidance’ directing all public bodies and major utilities to ‘take nature conservation into account’ when deciding their strategies and activities. In Sheffield (a major metropolitan district that subsumed functions from the old South Yorkshire County Council in the early 1980s), priority areas for countryside and environmental policy were: a) countryside access, b) countryside management, c) nature conservation, and d) trees & woodlands. Some examples of policies are given in Box 1.

In the 1990s, key policy thrusts changed with the 1992 Rio Convention to ideas based around ‘sustainable development’ (Brundland, 1987) and linked to the ‘Agenda 21’ declaration. Agenda 21 was a non-binding action plan of the United Nations from the Earth Summit (UN Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992). This is an action plan for the UN and partners like other global organisations, and national governments, carried out at local, national, and global levels. In the UK, the Environment Act of 1995 (Anon., 1995) placed a duty on Ministers to guide environmental agencies on objectives and how they contribute to sustainable development. In particular, many local authorities such as Sheffield City Council adopted Local Agenda 21 coordinated by a ‘Local Environment Forum’ and less-formal community-facing liaison forums.

By the late 1990s, nature conservation responded with national conservation agency and NGO ‘Biodiversity Action Plans’ (BAPs) interpreted locally by LBAPs. But by the 2000s, with local authority resources increasingly depleted the processes were largely devolved to local Wildlife Trusts (in Sheffield for example, see S&RWT (2012)). Key local authority services of countryside management, tree and woodland management, and ecological advisory provision lost both resources and political influence.

Under the coalition government came policies for local government based around the ‘Big Society’ (Cabinet Office, 2010), and ‘localism’, and strengthening of New Labour’s solution to local authority funding though Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs). The Localism Act (Anon., 2011) aimed to devolve powers from English local government to move decision-making from central government to individuals and communities at neighbourhood level. However, as the Sheffield case-study shows, the results have sometimes been catastrophic for democratic processes. Rapidly-shrinking local authority budgets and related service-cuts have led to partnerships between major, resource-rich, multi-national companies and local government.

Unexpected consequences of PFI agreements run counter to localism and ‘Big Society’ agendas with contractual issues that are normally subject to scrutiny and public transparency, being classed as commercially confidential and access often tightly restricted. Finally, an additional policy change between New Labour and Coalition governments was the closure of Regional Development Agencies (RDAs) which previously provided regional resources and direction for environmental matters. This left policy matters of constituent local authorities more isolated since the RDAs previously set regional targets for environmental sustainability that influenced street-tree management.

In the early 2000s a significant change occurred with most local authorities moving from committee-based governance to centralised decision-making by a small executive group. This was a shift from ‘power-sharing’ to ‘power-hoarding’ with local executives having reduced constraints on decision-making and resource allocation. The reform agenda was to streamline local democracy to decision-making by small Westminster-type executive groups accountable to ‘backbench’ councillors (in between elections) and the public (at elections). This shift in the nature of local governance, combined with pressures of central government-imposed cutbacks, is the institutional context understanding the street tree problem.

Part II – ‘No stump city’: a case-study of urban governance

These changes in political process had major implications for street-tree decision-making. As stated by the responsible Sheffield cabinet member, he ‘……was the democratic process and there was no need for further public consultation. The proposals from AMEY passed over his desk and he approved them as the democratically-elected member….’ (Councillor Jack Scott, Green Party community meeting, October 2013).

In 2007, Sheffield City Council commissioned York-based Elliott Consultancy to report on its highways trees. Around three per cent of the city’s street-trees (approximately 1,000 trees) might need to be removed. This was the result of long-term neglect dating back to the 1980s. Ten years later nearly 7,000 street trees had been felled with reports of plans to fell up to 17,500 more (i.e. 50 per cent)1 most of which are completely healthy (Bramley, 2018; Clark, 2018; Burn, 2018a; Sheffield Tree Action Groups, 2018). This issue informs and underpins a broad range of tensions, contradictions and challenges for local governance, in general, and ecological governance, in particular. This section does not provide detailed accounts of this case-study as several reports and explanatory documents already exist. Instead we provide a brief overview to explore the core argument about the ‘street-tree paradox’; the tension between increasing evidence of socio-economic benefits of street-trees and of systematic felling of street-trees to save money. Sheffield is one example of this phenomenon but it is not unique. Newcastle-upon-Tyne has cut 8,414 street-trees, Birmingham 9,200 in seven years, and the London boroughs, 47,000 (Pidd, 2018; Kirby, 2017).

The Sheffield ‘Streets Ahead’ project is a 25-year Private Finance Initiative (PFI) undertaking transformation works on Sheffield’s roads, pavements and bridges which includes improvement and on-going maintenance of roads, footways, highway trees, traffic signals, and street-lights. By 2012 / 2013, major problems emerged with tree-related aspects and the community-interface of the tree removal and replacement. Following a rise in public anxiety, a meeting between one of the authors (Rotherham) and AMEY’s street tree managers revealed that AMEY had signed the street-tree work as a peripheral element to the core highways-engineering element of the £2.4 billion contract. Furthermore, they had no knowledge of existing City Council strategies or policies relating to trees, environment, nature conservation, or public engagement. It became clear that AMEY had not considered local environmental policies (or associated constraints or costs), and neither had the City Council officers negotiating the contract raised environmental concerns. By 2013, as tensions across the city rose, both organisations (i.e. Sheffield City Council and AMEY) in the PFI partnership found themselves locked into legally-binding contracts ignoring tree conservation commitments. Additionally, each party used the contract to engage in ‘blame games’ (Hood, 2010) whereby each party deflected responsibility for inability to stop felling healthy street-trees.

AMEY officers were advised the situation was ill-advised, untenable, and likely to be environmentally-damaging and unpopular. Public-facing interactive meetings with expert and stakeholder presentations and panels were held in 2013 and 2014, followed by ‘Action for Woods and Trees’ workshops in May 2015, October 2016, and an evening event in November 2016.

Throughout the early public debate City Council and AMEY both claimed that they were only doing what the commissioned independent report (Elliott Consultancy Limited, 2007) had advised. However, in 2016 it was clarified that the review did not support the actions later taken by Sheffield City Council. Details of the Elliott findings confirmed that the recommendations were:

- Approximately 10,000 trees needed some form of remedial treatment.

- 25,000 trees required no work at present.

- Of those requiring work: »25 – immediate priority »1,200 – within 1 month priority »3,000 – within 3 months priority »4,000 – within 9 months »2,000 – if budget allowed.

Furthermore, the work recommended was as follows:

- 1,000 Felled;

- 1,500 To deadwood or crown-clean;

- 2,900 To crown-lift;

- 550 To crown-reduce;

- 241 To crown-reduce or consider removal.

Importantly, the report did not suggest that 70% of the street-trees were nearing the end of their life; something reported by both AMEY and Sheffield City Council in defence of their actions which by 2017 had already felled 5,000+ trees.

A survey report by Crane (2016) highlighted how professional standards of arboricultural ‘good practice’ had not been followed and that there were no genuine practical reasons for most removals. Very often two adjacent trees exhibited exactly the same degree of minor disruption to kerbs – or similar issues – but just one of the trees had been condemned. In January 2017, the Institute of Chartered Foresters published a report stating:

Sheffield was widely hailed as one of Europe’s greenest cities, but it is rapidly gaining an international reputation as the place where they are felling street trees on an industrial scale. Local democracy seems to be unravelling before an international audience as the wishes of local communities are ignored and healthy trees with decades of life left in them are felled causing significant loss of tree benefits. It is a political problem and it will be for the politicians to find a solution, with issues way beyond the remit for tree experts to resolve (Barrell, 2017).

A further report by qualified arborists in March 2017 supported the conclusions of previous expert reports. It also calculated that using the standard Capital Asset Value for Amenity Trees (CAVAT) methodology, street-trees with a total asset value of over £66 million had been lost to the city (see also Nielan, 2016). The Council admitted that in their appraisal, no asset valuation had been undertaken (SCC, 2016, 1). A host of professional bodies, arboriculturalists, and technical engineering specialists has examined the Sheffield street-tree policy and the conclusion of Steve Frazer (2017), writing for the Landscape Institute, was: ‘That I am aware of, there are no public examples of a technical expert independent of the contract in support of the current council policy for felling.’2

Issues that have proved especially contentious included the felling of World War One memorial trees (see Halliday, 2017). This was despite considerable public protest and appeals from the descendants of the fallen for whom the trees are a memorial. Another controversy concerns the ‘Independent Tree Panel’ which was established retrospectively by Sheffield City Council, but whose recommendations were mostly over-ruled by AMEY contractors. It was recently announced that the authority was to pay AMEY an additional £700,000 in compensation for delays resulting from the deliberations of the panel (Burn, 2018b).

In June 2018, the Secretary of State for Environment appointed a national ‘Tree Champion’ to stop the unnecessary felling of trees and boost planting rates, with the intention of ‘bring[ing] together mayors, city leaders and local government to prevent the unnecessary felling of street trees, while also backing the introduction of a new duty for councils to properly consult communities before removing trees’ (see Laville, 2018). This case-study leads to consideration of the wider implications.

Part III – Implications

Our central argument is the emergence of a ‘street-tree paradox’ in many cities and towns. This paradox revolves around the need to balance increasing evidence of socio-economic value of trees with the pressures to govern in an age of austerity when felling street-trees to save future maintenance costs seem politically attractive. It is suggested that that the paradox is ultimately irrational since social, environmental, and economic benefits of street-trees far outweigh financial costs of maintenance. However, in the case of Sheffield, the existence of a long-term PPP has to a great extent severed traditional connections between governors and governed to leave the public frustrated by a lack of political responsiveness. Although the broader implications of this case-study are many and complex, it is possible to tease out three main insights, each with wider implications for environmental governance. They also take us from a macro-political focus on public governance and increasingly blurred boundaries between public and private sectors, to a meso-political focus on community-engagement mechanisms, co-design, co-production and co-delivery of services. The arguments progress to micro-level consideration of individuality and why street-trees matter.

The case-study provides an almost perfect example of what Peters and Pierre (2004) described as ‘the Faustian bargain’ of contemporary public governance. The ‘bargain’ is relatively simple in that private sector organisations promise to increase levels of economic efficiency and save money. But this is at the cost of democratic process in terms of the derogation of traditional forms of political accountability, expectations of transparency and freedom of information, and the transfer of public funds into private profits. This interpretation ‘fits’ the Sheffield case-study. In a time of extreme financial cutbacks the Council reluctantly traded a degree of direct democratic control for undertakings in relation to low-cost service provision not possible through direct public provision. When significant sections of the local community complained about the nature of this ‘bargain’ in relation to street-trees the local political system was unable to resolve the tensions. Local democracy had been short-circuited or decommissioned resulting in a policy breakdown that has attracted major international attention, at times descending into farce.

The problem with the ‘bargain’ offered by PPPs such as the Sheffield example is that they are unable to deliver efficiency savings initially promised. The vaunted ‘risk-transfer’ on which the deal is based fails to materialise. When problems occur the public sector is often obliged to ‘step in’ and resume control because vital public services cannot be allowed to simply ‘fail’ like private market commodities. Put slightly differently, the ‘rule of rescue’ (Flinders and Wood, 2015) prevents the public sector from taking full advantage of the theoretical ‘deal’ or ‘bargain’ because it cannot simply walk away. Interesting in the Sheffield case-study, and demanding further research, is the manner in which the City Council consistently refused to engage even in conversations about the possibility of ‘rescuing’ the street-trees through contractual renegotiation. The City Council insisted that it was too expensive to renegotiate and therefore its hands are tied. However, nobody outside a handful of senior councillors, council officers and AMEY-staff are actually privy to the detailed provisions for amendment within the contract. They cannot therefore make a reliable assessment of the true costs of (non-)action.

It is possible to position this case-study within a vast body of literature on the ‘end’, ‘suicide’ or ‘survival’ of democracy (Flinders, 2012; 2017; Finders and Wood, 2015, 2018). This literature all tends to highlight the rise of anti-political sentiment and deep social frustrations that ‘everyday’ political experiences like those associated with the Sheffield street-trees may fuel. However, such broad analytical horizons are side-lined by the need to focus-down on why this case-study matters in understanding the potential role of local communities in policy-making.

The economic austerity imposition of far-reaching budgetary cuts on local authorities has created challenges for local politicians and officials in making difficult decisions about reduction or termination of specific public services. In many ways the great theoretical benefit of PPPs is that they offer ‘more for less’ in service delivery whilst also offering ‘buy now, pay later schemes’. The financial costs of projects are to a large part deferred into the future. In this way, PPPs offer a tool of ‘depoliticisation’ in that responsibility for key public services transfer away from the direct control, and direct responsibility, to organisations having only tenuous relationships with the public. This triggers concerns about the ‘hollowing-out’ of local democracy.

However, there are alternative ways of dealing with difficult decision-making in times of increasing demands but shrinking resources. These may involve deepening democratic structures and engaging with communities through commitment to co-design, co-creation, or co-production of public services. In these cases local authorities work in partnership with communities to address funding challenges. The United Kingdom has been at the forefront of this agenda and the co-production of many public services is currently an administrative fashion within the public sector. For example, the Local Government Association’s New Conversations: LGA Guide to Engagement (2017), provides step-by-step guidance for local authorities, framing co-production in terms of money-saving and public trust-building potential. It encourages local authorities to not just embrace co-production but to ‘surpass expectations’.

Initiating co-productive relationships in designing and delivering public services is generally viewed as a way to re-engage local communities, building trust with service-users, draw on previously untapped civic capacities, and trigger ‘democratic innovation’ (Smith, 2009). The tension within this agenda and with the launch of any ‘new conversations’ is that it relies on those wielding constitutional power at the local level (i.e. portfolio-holding councillors) being willing or brave enough to open-up policy-space to new voices and ideas. The hope is to find new ways or resources through which austerity impacts might be managed in the least problematic manner. Nevertheless, research reveals that many politicians are unwilling to innovate or take risks that may dilute their power. In other cases, processes of co-design, co-creation, and co-production have been launched as token gestures that mask the continuation of elite, insular political structures (Flinders, 2012; 2017; Finders and Wood, 2015, 2018). As Archon Fung argued, ‘In most contexts, the organizations and leaders who possess the resources and authority to create significant participatory governance initiatives simply lack the motivation to advance social justice through those projects’ (Fung, 2015, p.521). Criticisms have also been made of the limitations of co-production in the UK government’s ‘Big Society’ initiative (Martin, 2012) and the engagement of patients in ‘co-productive’ health policy initiatives (Carter and Martin, 2017).

Conclusions

This article asked three main questions and many lesser ones. Firstly we considered whether there are conflicts between evidence of environmental, economic, and social benefits associated with urban street-trees and the directions of national political policies and their local manifestations. It is clear that the case study established that this is so. Second we raised the question of whether urban street-tree management might be a ‘lightning rod’ for wider matters of local, environmental democracy, and again we argue that this is the case. Finally, the work asked if the case study suggests fundamental problems in the adoption of PFI projects for delivery of local environmental services, and again, we suggest that it does.

Locating this common tension between aspirations, policy and practicality back within the bounds of our research and case study is interesting. The study highlights a stark ‘rhetoric-reality gap’ on the part of the City Council. As Sheffield City Council’s own State of Sheffield (2017) report acknowledged ‘There is very clearly a public appetite to participate in consultation, be involved in the co-design of services and other processes, in influencing and shaping plans and actions’. This report concluded that ‘[M]ore should be done to inform people, engage them in developing policy and contributing to service provision.’ And yet this pronouncement completely overlooks how a significant section of the city’s population had been campaigning for a greater role in co-designing specific local service (i.e. street-tree policy) for several years.

This brings us to our final theme and to a focus on the micro-politics of ‘everyday’ life and why street-trees seem to inflame such intense political passions. This is a critical point. Although our case study focuses on Sheffield as an extreme example of ‘the politics of street-trees’ it is possible to highlight similar tensions, debates and campaigns all over the world. This is illustrated by Jill Jones’ book Urban Forests (Jones, 2016). So what makes street-trees apparently so important to their local communities? From the research for this case-study two issues appear critical. The first relates to the role of emotions and the pace of modern life. What Zygmunt Bauman (2000) labelled ‘liquid modernity’ has undermined a number of social anchorage points through which people make sense of the world. It has also demanded increasing levels of mobility and professional change. In this context, the street-tree may assume a socially symbolic role in the sense of its tangible solidity, its physical anchorage to a specific place, its ability to become a marker-point in people’s lives that reflects the passage of time and the seasons. A tree is tactile and shapes the urban environment; often shaping everyday life in subtle ways only missed once it is gone. Maybe the street-tree’s role is as a physical and symbolic reference point for local communities. This is where children may climb and families picnic, people seek shelter or shade in, or simply admire the colour of the blossom or the richness of the autumnal leaves. In a historical period where stability appears increasingly precarious as a social commodity, street-trees become potentially salient political issues (often to the surprise of local politicians).

That politicians are often surprised when plans to fell street-trees generate such emotionally-charged backlash provides a link with a second key issue that of trees as ‘lightning rods’. What is particularly interesting about the Sheffield research was how the street-tree protests evolved to become a far wider campaign about the nature of local democracy. Put slightly differently, the street-trees issue became a ‘lightning rod’ through which a whole range of frustrations and concerns about the nature of contemporary politics was channelled and focused. This was reflected in the emergence of a local campaign called ‘It’s Our City!’ with its roots in the street-tree campaign but focused on wholesale reform of local governance. This grew to the extent that in June 2018 it launched a campaign to secure a local referendum on whether to reintroduce the traditional committee-based decision-making system within the City Council. This was to shift back to a power-sharing model of governance with the power of the Leader significantly reduced. Whether this referendum will happen is uncertain, as it requires a petition to be signed by over five per cent of the city’s eligible voters. However, it is clear that political decisions to remove street-trees based on financial calculations in a period of austerity is interpreted by many local people as symptomatic of broader concerns about politicians being ‘disconnected’, ‘out of touch’, ‘irrational’, or ‘uncaring’. Whether such interpretations are fair or valid is beyond the scope of this concluding section. Politics is, as Bernard Crick explained in his classic book In Defence of Politics (Crick, 1962), inevitably messy. Nevertheless, what appears clear is that the politics of street-trees matter due to physical and representational location at the intersection of people, place, and policy-making.

2 Sheffield City Council’s arguments in favour of felling frequently refer to a street tree survey conducted by Elliott Consultancy in 2007. Council documents and statements by councillors and AMEY have claimed that this report states that 75% of the city’s trees were reaching the end of their natural life (e.g. Dore, 2017). This claim is not actually supported by the Elliott survey which suggested that 1,000-1,241 street trees (i.e. 3% of the total stock) were in need of replacement; and 4,950-5,191 (14%) needed some maintenance work but certainly not felling.

Dr Ian Rotherham, Department of the Natural and Built Environment City Campus, Howard Street, Sheffield, S1 1WB. Email: i.d.rotherham@shu.ac.uk

Adams, J. (2007) Dangerous Trees? Arboricultural Journal, 30, 2, 95-104. CrossRef linkAnon. (1981) Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. London: HMSO.

Anon. (1983) Green Belt Plan. Sheffield: Sheffield City Council.

Anon. (1987a) A Strategy for Countryside Management. Sheffield: Sheffield City Council.

Anon. (1987b) Out and About in Sheffield’s Countryside. A Statement of the City Council’s policies on Access to Sheffield’s Countryside. Sheffield: Sheffield City Council.

Anon. (1987c) Woodland Policy. Sheffield: Sheffield City Council.

Anon. (1990) Charter for the Environment. Sheffield City Council, Sheffield

Anon. (1994) River Rother Wildlife Strategy. Matlock, Derbyshire: Derbyshire County Council and partners.

Anon. (1995) Environment Act 1995. London: The Stationery Office.

Anon. (1999) A Strategy for Countryside Management. Sheffield: Sheffield City Council.

Anon. (2010) Building the Big Society. London: Cabinet Office.

Anon. (2011) Localism Act 2011. London: The Stationery Office.

Anon. (2017) Sheffield trees dispute: Council legal costs hit £250K. BBC News, 28 September 2017. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-south-yorkshire-41417810

Anon. (2018) i-Tree Eco. US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service, Davey Tree Expert Company, International Society of Arboriculture, Society of Municipal Arborists, Arbor Day Foundation, and Casey Trees. Forest Research. Available at: https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/research/i-tree-eco/ [Accessed: June 2018]

Ball, D.J. (2007) The Evolution of Risk Assessment and Risk Management’: A Background to the Development of Risk Philosophy. Arboricultural Journal, 30, 2, 105-112. CrossRef link

Barrell, J. (2014) BS 8545: more of the same or something different? Municipal Tree Officers Association Newsletter, (Summer 2014).

Barrell, J. (2017) Tree benefits; the missing part of the street tree cost benefit analysis equation. Available at: https://www.charteredforesters.org/2017/02/tree-benefits/

Bauman, Z. (2000) Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Blunt, S.M. (2008) Trees and Pavements – Are They Compatible? Arboricultural Journal, 31, 2, 73-80. CrossRef link

Booth, J.A. (2005) Street trees – A Sustainable Stakeholder Strategy. Unpublished MSc Dissertation. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University.

Booth, J.A. (2006) Developing a Sustainable Community Strategy for Street Trees II. Arboricultural Journal, 29, 3, 185-202. CrossRef link

Bownes, J. S., Riley, T. H., Rotherham, I. D. and Vincent, S. M. (1991) Sheffield Nature Conservation Strategy. Sheffield: Sheffield City Council.

Bramley, E.V. (2018) For the chop: the battle to save Sheffield’s trees. The Guardian, Sunday 25th Feb 2018. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/feb/25/for-the-chop-the-battle-to-save-sheffields-trees

Britt, C. and Johnston, M. (2008) Trees in Towns II: A New Survey of urban trees in England and their condition and management. London: Department for Communities and Local Government.

Brundland G.H. (ed.) (1987) Our Common Future (The Brundtland Report). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

BSI (2010) BS 3998: 2010 Recommendations for Tree Work. Bristol: British Standards Institution.

BSI (2012) BS 5837: 2012 Trees in Relation to Design, Demolition and Construction – Recommendations. Bristol: British Standards Institution.

Burn, C. (2018a) Sheffield Council has been forced to reveal a hugely-controversial PFI highways maintenance contract contains a target to cut down almost half of the city’s 36,000 street trees and replace them with saplings. Yorkshire Post, Saturday 10 March 2018. Available at: https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/our-region/south-yorkshire/sheffield/sheffield-council-forced-to-reveal-target-to-remove-17-500-street-trees-under-pfi-deal-1-9056942

Burn, C. (2018b) Sheffield Council pays £700,000 compensation bill for tree-felling delays. Yorkshire Post, Monday 18 June 2018. Available at: https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/sheffield-council-pays-700-000-compensation-bill-for-tree-felling-delays-1-9210254

Carter, P. and Martin, G. (2017) Engagement of patients and the public in NHS sustainability and transformation: An ethnographic study. Critical Social Policy, 38, 4, 707-727. CrossRef link

Clark, J. (2018) Sheffield Council reveals plan to chop almost half city’s street trees. New Civil Engineer, 12 March, 2018. Available at: https://www.newcivilengineer.com/business-culture/sheffield-council-reveals-plan-to-chop-almost-half-citys-street-trees/10029005.article

Countryside Commission (1978) Local Authority Countryside Management Projects: A guide to their organisation. Cheltenham: Countryside Commission.

Countryside Commission (1979) Countryside Rangers and Related Staff. Cheltenham: Countryside Commission.

Countryside Commission (1981) Countryside Management in the Urban Fringe, Report No. CCP 136. Cheltenham: Countryside Commission.

Countryside Commission (1987) Recreation 2000. Policies for Enjoying the Countryside, Report No. CCP 234. Cheltenham: Countryside Commission.

Crick, B. (1962) In Defence of Politics. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Cullen, S. (2007) Putting a Value on Trees: CLTA Guidance and Methods. Arboricultural Journal, 32, 1, 21-44. CrossRef link

Cumber, R. (2017) Tree-felling panel expected to cost Sheffield tax-payers at least £1m. Sheffield Star, Friday 12 May 2017. Available at: https://www.thestar.co.uk/our-towns-and-cities/sheffield/tree-felling-panel-expected-to-cost-sheffield-tax-payers-at-least-1m-1-8540349

Darn, R. (2018) Exploring the suburbs of Sheffield. Yorkshire Life, 16th August 2018. Available at: https://www.yorkshirelife.co.uk/out-about/places/sheffield-suburbs-1-5635507

Done-Johns, A. (2018) Sheffield tree felling cost police £47K in overtime in less than a month. Sheffield Star. April 20th 2018. Available at: https://www.thestar.co.uk/news/sheffield-tree-felling-cost-police-47k-in-overtime-in-less-than-a-month-1-9127654

Elliott Consultancy Ltd (2007) Sheffield City Highways Tree Survey 2006 – 2007. York: Elliott Consultancy Ltd.

Ennos, R. (2012) Quantifying the cooling benefits of trees. In: Johnston, M. and Percival, G. (eds) Trees, People and the Built Environment. Forestry Commission Research Report. Edinburgh: Forestry Commission.

Flinders, M. (2012) Defending Politics: Why Democracy Matters in the 21st Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. CrossRef link

Flinders, M. (2017) What Kind of Democracy is This?: Politics in a Changing World. Bristol: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Flinders, M. and Wood, M. (2015) When Politics Fails. New Political Science, 379, 3, 363-81. CrossRef link

Flinders, M. and Wood, M. (2018) Nexus Politics. Democratic Theory, 5, 2, 56-81. CrossRef link

Fung, A. (2015) Putting the public back into governance. Public Administration Review, 75, 4, 513-522. CrossRef link

Gill, S., Handley, J., Ennos and A. and Pauleit, S. (2007) Adapting Cities for Climate Change: The Role of Green Infrastructure. Built Environment, 3, 1, 115-133. CrossRef link

Halliday, J. (2017) Sheffield council votes to fell trees planted in memory of war dead. The Guardian, Thursday 14th December 2017. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/dec/14/sheffield-council-votes-fell-trees-planted-memory-war-dead

Helliwell, R. (2008) Amenity Valuation of Trees and Woodlands. Arboricultural Journal, 31, 3, 161-168. CrossRef link

Hobson, D. (2016) Council claim it will cost £26 million to save Sheffield trees. Sheffield Star, Monday 08 February 2016. Available at: https://www.thestar.co.uk/news/council-claim-it-will-cost-26-million-to-save-sheffield-trees-1-7718982

Hood, C. (2010) The Blame Game. Princeton: Princeton University Press. CrossRef link

Johnston, M. (2010) Trees in Towns II and the Contribution of Arboriculture. Arboricultural Journal, 33, 1, 27-41. CrossRef link

Johnston, M. (2017) Street Trees in Britain – A History. Oxford: Windgather Press.

Jones, J. (2016) Urban Forests: A Natural History of Trees and People in the American Cityscape. Viking Press, New York.

Jones, M. (2009) Sheffield’s Woodland Heritage. 4th Edition. Sheffield: Wildtrack Publishing.

Kirby, D. (2017) Revealed: The trees on our streets are being felled at a rate of 58 a day. i-News, Friday March 31st 2017. Available at: https://inews.co.uk/news/environment/revealed-suburban-trees-felled-rate-58-day/

Laville, S. (2018) Michael Gove appoints UK ‘Tree Champion’. The Guardian, 13 June 2018. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/jun/13/michael-gove-appoints-uk-tree-champion

Lockhart, J. (2009) Green Infrastructure: The Strategic Role of Trees, Woodlands and Forestry. Arboricultural Journal, 32, 1, 33-50. CrossRef link

Maher, B.A., Ahmed, I.A.M., Davison, B., Karloukovski, V. and Clarke, R. (2013) Impact of Roadside Tree Lines on Indoor Concentrations of Traffic-Derived Particulate Matter. Environ. Sci. Technol, 47, 23, 13737-13744. CrossRef link

Martin, G. P. (2012) Public deliberation in action: emotion, inclusion and exclusion in participatory decision making. Critical Social Policy, 32, 2, 163-183. CrossRef link

National Tree Safety Group (NTSG) (2011) Common Sense Risk Management of Trees, Guidance on trees and public safety in the UK for owners, managers and advisers. Edinburgh: Forestry Commission.

Papastavrou, V. (2010) Determining Pedestrian Usage and Parked Vehicle Monetary Values for Input into Quantified Tree Risk Assessments – Two Case Studies from Urban Parks in Great Britain. Arboricultural Journal, 33, 1, 43-60. CrossRef link

Peters, G. and Pierre, J. (2004) ‘Multi-Level Governance and Democracy: A Faustian Bargain?’ In: Flinders, M and Bache, I. (eds.) Multi-Level Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. CrossRef link

Pidd, H. (2018) Newcastle fells more trees than any other UK council. The Guardian, Sun 3rd June 2018. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jun/03/newcastle-fells-more-trees-than-any-other-uk-council

Price, C. (2007) Putting a Value on Trees: an economist’s perspective. Arboricultural Journal, 30, 1, 7-20. CrossRef link

Rotherham, I.D. (2010a) The Politics and Economics of Urban Street Trees. Unpublished paper presented at ‘Do street trees have a future?’ UNESCO UK-MAB UCL Wednesday 12th May 2010, unpublished conference paper.

Rotherham, I.D. (2010b) Thoughts on the Politics and economics of Urban Street Trees. Arboricultural Journal, 33, 2, 69-76. CrossRef link

Rotherham, I.D. (2013) The impacts on active countryside tourism of the rise and fall of countryside management. Proceedings of Active Countryside Tourism, Leeds, 23-25 January 2013, Leeds.

Rotherham, I.D. (2014) Eco-History: A Short History of Conservation and Biodiversity. Cambridge: The White Horse Press.

Rotherham, I.D. (2015) The Rise and Fall of Countryside Management. London: Routledge. CrossRef link

Rotherham, I.D. (2018) Steel City: An Illustrated History of Sheffield’s Industry. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing.

Sheffield Star (2009) The curse of Betjeman. Sheffield Star, 8th July, 2009. Available at: https://www.thestar.co.uk/lifestyle/features/the-curse-of-betjeman-1-289383

Sheffield Tree Action Groups (2018) 5,500 of Sheffield’s street trees have been chopped down in the last five years – another 12,000 will go over the next 20 years. Available at: https://savesheffieldtrees.org.uk/

Simson, A. (2008) The Place of Trees in the city of the Future. Arboricultural Journal, 31, 2, 97-108. CrossRef link

Stovin, V.R., Jorgensen, A. and Clayden, A. (2008) Street Trees and Stormwater Management. Arboricultural Journal, 30, 4, 297-310. CrossRef link

S&RWT (2012) Sheffield Local Biodiversity Action Plan. Sheffield: Sheffield and Rotherham Wildlife Trust.

Syal, R. (2018) Revealed: the £200bn cost of PFI projects. The Guardian, Thursday 18th January 2018, p1.

Thomas, A.M., Pugh, A., MacKenzie, R., Whyatt, J.D. and Hewitt, C.N. (2012) Effectiveness of Green Infrastructure for Improvement of Air Quality in Urban Street Canyons. Environ. Sci. Technol, 46, 14, 7692-7699. CrossRef link

TDAG (2012) Trees in the Townscape: A Guide for Decision Makers. London: Trees and Design Action Group TDAG.

TDAG (2014) Trees in Hard Landscapes: A Guide for Delivery. London: Trees and Design Action Group TDAG.

Trowbridge, P.J. and Bassuk, N.L. (2004) Trees in the Urban Landscape: Site Assessment, Design, and Installation. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons, Inc.

UK Roads Liaison Group (2013) Well-Maintained Highways – Code of Practice for Highway Maintenance Management. London: UKLRG.