Abstract

This paper examines socio-spatial inequalities with reference to the post-Olympics East Village – the former Athletes’ Village – located in Stratford in the London Borough of Newham. The East Village neighbourhood has been praised within urban policy circles because of its mixed-tenure housing, including a relatively high percentage of ‘affordable housing’. It is also claimed to be a space of social mixing, including in relation to the rest of East London. This paper examines these claims with reference to research undertaken at the East Village with residents and officials. Survey data reveals how East Village is a majority white neighbourhood with a large professional-managerial ‘salariat’, and as such is quite distinct in both class and ethnic terms from the rest of Stratford and Newham. These social differences are reflected in the interview data which examine how ‘othering’ processes occur on the part of middle-class East Village residents, both externally in relation to the rest of Stratford, but also internally within East Village itself. These residents display a ‘mixophobic’ (Bauman, 2013) reaction towards Stratford via territorial stigmatisation, and towards East Village social renters via housing tenure stigmatisation. The aims of social mixing and affordable housing are far from being realised within the East Village regeneration scheme.

Introduction

This paper examines socio-spatial inequalities in relation to the regeneration of East London. It focuses on ‘social mixing’ and ‘affordable housing’ policies with reference to research undertaken on the East Village – the rebranded London 2012 Olympic Games’ Athletes’ Village – located within the Stratford area of the London Borough of Newham.

Poverty, deprivation and overcrowding are of long-standing nature in East London, currently the most ethnically diverse part of the UK (Lindsay, 2008; Elahi and Khan, 2016; White, 2020). The rationale for the regeneration element of the London 2012 Olympic Games was to bequeath a ‘legacy’ to the six Host Boroughs – Barking and Dagenham, Hackney, Newham, Greenwich, Tower Hamlets and Waltham Forest – which would mean that their deprivation levels would ‘converge’ with the rest of London over a 20-year period (Cohen and Watt, 2017). The London Candidature File – the bidding document that the London 2012 team presented to the International Olympic Committee – recognised the great need for affordable housing in East London (London 2012, 2004). Therefore, a key part of the legacy was the creation of new housing in and around the Olympic Park, and one of the major sites for achieving this legacy was and is the mixed-tenure East Village: ‘With a good number of family-sized homes, the East Village would provide much-needed affordable housing for east Londoners and, for many, this will be the Olympic Legacy’ (Meredith, 2012).

This paper interrogates these policy aims and claims regarding social mixing and affordable housing by drawing upon research with East Village residents and officials, as well as documentary analysis. The paper begins by outlining the East London context, one characterised by entrenched poverty and deprivation, but also by a series of regeneration programmes including Stratford City and the 2012 Olympic Games which have had dramatic impacts on Newham and especially on the Stratford area. The literature regarding social mixing and affordable housing is then discussed before we outline the East Village residential development and summarise the research methods. The empirical findings are presented in three sections. First, the East Village residents’ socio-demographic profiles in terms of class, ethnicity and age are analysed and compared to the Stratford and New Town ward and the borough of Newham. Second, the socio-spatial perceptions and experiences of middle-class East Village residents are analysed vis-à-vis the rest of Stratford, and third their socio-spatial perceptions and experiences are analysed in relation to social renters within East Village. The conclusion highlights increased socio-spatial inequalities within Newham, and how the policy notions of social mixing and affordable housing are ideological rather than substantive in relation to the East Village neighbourhood.

Inequality, regeneration and gentrification in East London

East London has been a byword for housing squalor and poverty dating back to Charles Booth’s poverty studies at the end of the 19th century, and there is evidence that overcrowding remained persistent in certain areas of East London from the 1880s right up until 2001 (Lindsay, 2008). If anything, poverty and deprivation intensified in East London during the late 20th century due to widespread unemployment and job losses resulting from deindustrialisation and closure of the docks (Foster, 1999; Hamnett, 2003).

As a response to such disadvantage, East London has been one of the UK’s major laboratories for urban regeneration, not only in terms of small-scale area-based initiatives, but also via major regeneration projects such as the 1980s’ London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC), Stratford City, and the 2012 Olympic Games (Foster, 1999; Bernstock, 2014, 2020). These large-scale regeneration programmes embraced extensive private residential and commercial property redevelopment, and they have certainly resulted in a dramatic physical transformation of the Docklands and Stratford areas of East London. What is questionable is how far such programmes have improved the lives of existing Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) and white working-class populations, many of whom continue to struggle with low income, precarious employment, overcrowding, homelessness and displacement (see inter alia Foster, 1999; Bernstock, 2014; Elahi and Khan, 2016; Kennelly, 2016; Thompson et al., 2017; Vadiati, 2020; Watt, 2020; White, 2020, 2021; Gillespie et al., 2021).

There is evidence from income data and the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) that aggregate levels of poverty and deprivation in East London have declined since the early 2000s, although the significance and causes of this decline remain the subject of debate (Hanna and Bosetti, 2015; Franshen, 2017). At the same time, such quantitative studies acknowledge that East London continues to experience severe problems: ‘inner East boroughs still have the highest proportions nationally of children and old people living in poverty [in England]’ (Hanna and Bosetti, 2015: 9). Furthermore, five out of the six Olympics Host Boroughs (except Greenwich) were ranked among the twenty most deprived local authorities in England in 2015, with Newham as the eighth most deprived (Smith et al., 2015: 47). Such persistent problems were recently spotlighted by how three East London boroughs – Newham, Barking and Dagenham, and Redbridge – formed the ‘Covid Triangle’ where Covid infections were amongst the highest in the country, reflective of the ongoing poverty, deprivation and overcrowding that continues to scar the lives of East Londoners and especially those from BAME backgrounds (Raval, 2021).

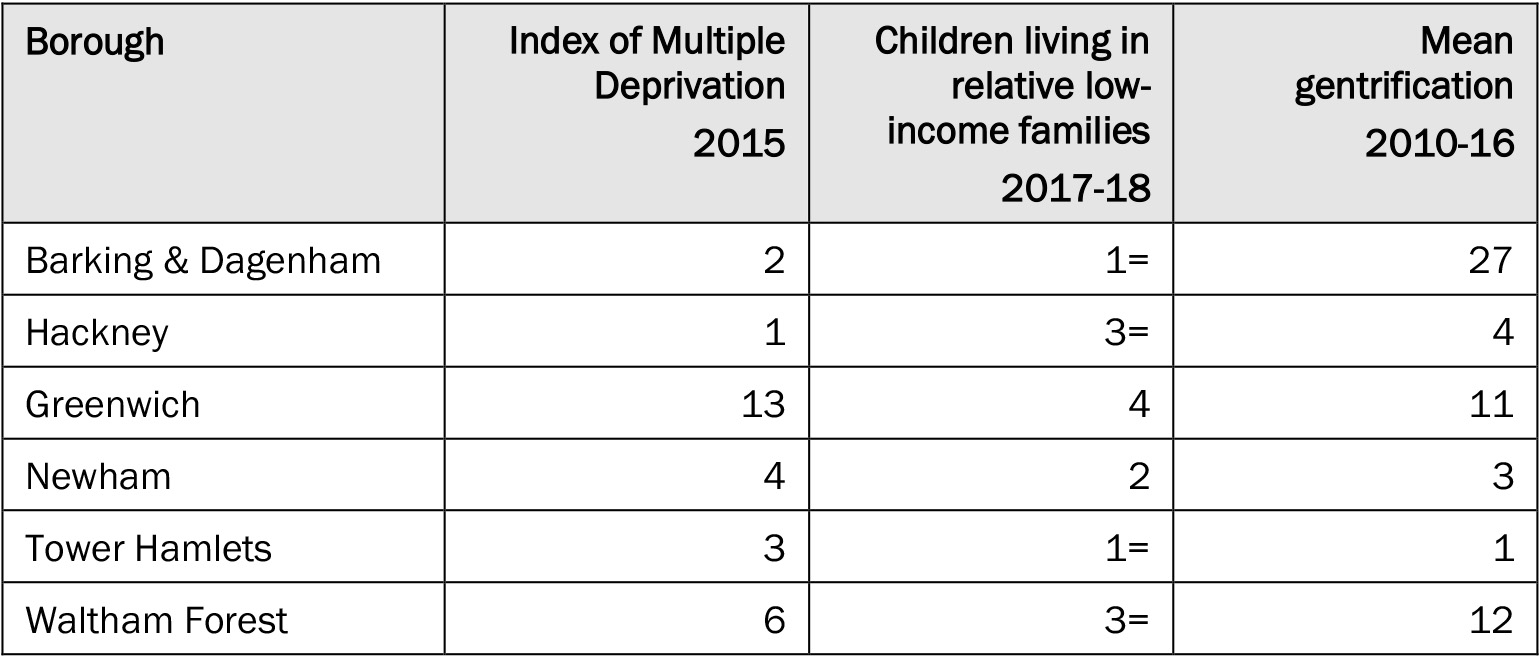

Table 1 shows the 2015 IMD rankings for the six Host Boroughs within London’s 33 local authorities (32 boroughs plus City of London). These boroughs (bar Greenwich) occupied five of the six worst ranked positions in London. Similarly, Table 1 shows how the Host Boroughs were also ranked high among London local authorities in terms of child poverty – children living in relative low-income families. Paradoxically, Table 1 also indicates how three out of the four local authorities which gentrified most across London between 2010 and 2016 were Host Boroughs; respectively Tower Hamlets (1st), Newham (3rd) and Hackney (4th) (Almeida, 2021: 10). What is striking about Table 1 is how these three boroughs appear at the top of both the IMD and child poverty London local authority rankings, but also for the gentrification index rankings. Therefore, these three East London boroughs are experiencing widening socio-spatial inequality, predicated upon ongoing poverty and deprivation co-existing with increased gentrification. This represents part of London-wide polarising trends under neoliberalism involving growing inequality and residential segregation at multiple spatial scales including expanding enclaves for the super-rich and elite, widening inequality between neighbourhoods (Cunningham and Savage, 2017; Shi and Dorking, 2020; Yee and Dennett, 2021), and heightened ‘micro-segregation’ within neighbourhoods consisting of ‘stark income polarities and distinct spatial geographies at a micro-scale’ (Keddie and Tonkiss, 2010: 67).

Regeneration is by no means the sole cause of gentrification in London (Hamnett, 2003, 2021; Keddie and Tonkiss, 2010; Almeida, 2021; Yee and Dennett, 2021). Nevertheless, regeneration has contributed towards ‘state-led gentrification’ which has been prominent in those inner London areas, such as the Elephant and Castle in Southwark and Woodberry Down in Hackney, which have been subject to large-scale physical renewal due to social housing estate demolition and redevelopment (Watt, 2021). State-led gentrification has also occurred in those parts of Newham which have witnessed property-based regeneration due to schemes such as the Canning Town and Custom House regeneration project, Stratford City and the 2012 Games (Bernstock, 2014; Watt, 2013, 2021). Such regeneration initiatives, alongside the earlier LDDC, have resulted in a plethora of professional jobs and new private housing that has primarily benefitted white middle-class incomers – gentrifiers – rather than the existing local multi-ethnic working-class population (Foster, 1999; Keddie and Tonkiss, 2010; Bernstock, 2014; Vadiati, 2020; Watt, 2021). A recent report by Almeida (2021: 10 and 49) has demonstrated how the high average level of gentrification within Newham is skewed by the intense gentrification that has occurred in the Stratford area where the East Village and many of the new upmarket housing developments are located. Such developments have emerged out of the Stratford City and 2012 Olympics regeneration schemes which themselves reflect Newham Council’s conscious strategy to drive Newham in general and Stratford in particular ‘upmarket’ via adopting a strategy of increased market housing to attract higher-income groups while neglecting new social housing provision (Bernstock, 2014, 2020; Watt and Bernstock, 2017) – aka state-led gentrification (Watt, 2013, 2021).

Social mixing, ‘affordable housing’ and class distinction

Social mixing – the development of new-build mixed-tenure neighbourhoods consisting of properties for private sale and/or rent alongside social rental housing – emerged as a prominent urban policy theme during the 1990s and has subsequently become policy orthodoxy across many parts of the world (Levin et al., 2022). Social mixing aims to promote ‘mixed communities’ whereby poor/working-class social tenants benefit socially and economically from living in close spatial proximity to affluent middle-class homeowners, for example via raising their aspirations and providing ‘bridging social capital’ in Robert Putnam’s terms (Watt, 2021). However, existing research provides limited evidence for such beneficent tenure mixing (Tunstall and Lupton 2010; Levin et al., 2022). On the contrary, many studies underscore how social mixing via new-build developments contributes towards heightened class and racialised divisions, including tenure stigmatisation by affluent homeowners directed against spatially proximate poor social tenants who in London are also often from BAME backgrounds (Davidson, 2010; Bretherton and Pleace, 2011; Lindsey, 2012; Horgan, 2020; Watt, 2021; Levin et al., 2022). Studies of mixed-tenure neighbourhoods in England have however tended to focus on private homeowners alongside social renters, with Bretherton and Pleace (2011) being one exception in also examining shared owners, a tenure category that is pertinent to the East Village case study examined here.

The second policy area that this paper examines is affordable housing. Although affordable housing was previously equated with social rental housing (provided by local authorities and housing associations), since 2000 it has become an increasingly polymorphic term. Affordable housing currently covers several intermediate tenures in-between social renting and market housing including shared ownership (part-buy, part rent), shared equity (shared ownership, no rent), and intermediate rent consisting of properties let at either 70 or 80 per cent of the market level (Preece et al., 2020; Sagoe et al., 2020). However, the umbrella term ‘affordable housing’ is increasingly regarded as a misnomer, especially in London where it ‘comprises anyone from council tenants spending an average £120 per week to those paying 80 per cent of market rents, a rate far exceeding feasible limits for working-class residents’ (Almeida, 2021: 17; see also Preece et al., 2020; Sagoe et al., 2020).

This paper draws upon Pierre Bourdieu’s (1984) theorisation of the relationship between social class and space, as well as Zygmunt Bauman’s concept of ‘mixophobia’ (2013). For Bourdieu (1984), class inequality is based not only on economic hierarchies, but also on cultural processes of distinction. Spatialising Bourdieu’s approach facilitates an understanding of how class inequalities are inter-meshed with physical space (Savage, 2011). Drawing on Bourdieu’s work, Davidson (2010) argues that the formation of a middle-class habitus in the residential ‘field’ may rely on the presence of the ‘other’, who, however, must be kept at a distance. Boundaries and oppositions are therefore not simply a consequence of class distinction, but are rather central to it, and developments are built in such a way that homeowners’ contact with social difference is minimised (ibid.). This creates ‘oases’ of socio-spatial exclusion predicated on fostering ‘selective belonging’ – a spatially restrictive place belonging based on middle-class sharing and valorising of an immediate privileged residential space, while nearby class and racialised ‘others’ are kept at a ‘safe’ distance (Watt, 2009).

Processes of social distinction may cause negative emotions in relation to class and racialised ‘others’ (Sibley, 1995). Bauman (2013: 31) associates the way in which the white middle classes experience otherness in contemporary cities with ‘mixophobia’, as manifested through feelings of anxiety about diversity and the drive towards residential ‘islands of similarity and difference’. Avoiding contact with otherness facilitates feelings of comfort and ease whereby there is a ‘natural fit’ between the residential neighbourhood as a field and the middle-class habitus – as in selective belonging (Watt, 2009).

East Village development and research methods

This paper is based upon primary research undertaken during 2017 which received ethical approval from the Department of Geography at Birkbeck, University of London (Corcillo, 2021). One primary data source used here is the resident East Village Survey (EVS). The EVS self-completion questionnaire was disseminated to 250 residents in three East Village locations: the gym, health centre and most popular café. Of these, 211 were completed. Questions covered residents’ previous address, length of residence, satisfaction with their neighbourhood and flat, housing tenure and socio-demographic backgrounds.

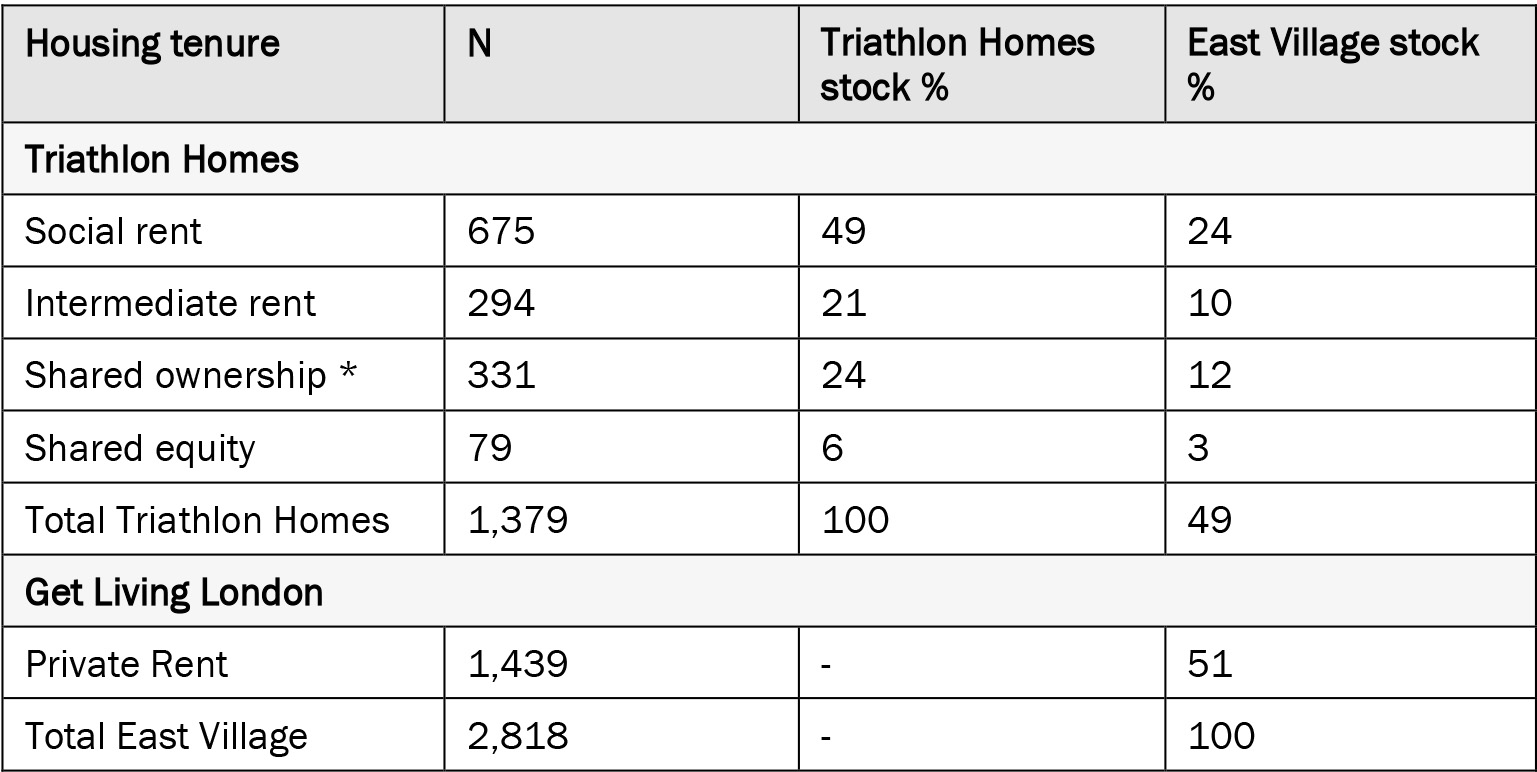

The EVS is not based upon a statistically representative sample of the resident population (approximately 6,000). Furthermore, the EVS under-represents social renters who make up 24 per cent of the total East Village households, as seen in Table 2 below, but only 18 per cent of the EVS sample. This latter discrepancy is likely to reflect how middle-class people are generally more willing than working-class people to participate in social research (Savage, 2015). We have attempted to counter-balance this by reweighting the EVS respondents by tenure such that the total East Village percentages in Tables 3 and 4 below reflect the actual percentage size of housing tenures within East Village in Table 2. Regarding representativeness, the EVS ethnic profile (discussed below) is very similar to that identified by Bernstock (2020) based upon data supplied by Triathlon Homes. We therefore argue that while the EVS is not based upon a statistically representative sample, it nevertheless provides a credible indicative summary of the neighbourhood’s socio-demographic profile. This profile can then be used alongside data from the 2011 Census to facilitate a socio-demographic comparison between the East Village neighbourhood, Stratford and Newham.

In addition to the EVS, the paper draws upon 49 semi-structured interviews with residents plus interviews with two housing managers. Residents were approached through invitation letters, emails, door knocking, as well as by asking survey participants if they were willing to be interviewed. Resident interviewees include 15 private renters, 15 social renters, 11 shared owners (two of whom had ‘staircased’ up to 100% ownership), and eight intermediate renters. Residents were asked about their homes, neighbourhood, surrounding areas and housing management. Housing manager interviewees were asked about planning, housing and place-making. Interviews lasted between 30 to 90 minutes. An inductive-iterative approach was adopted in order to work between the theoretical and conceptual framings and empirical material. Finally, the Triathlon Homes manager who was interviewed provided a range of unpublished policy documents on East Village housing tenure distribution and allocation policies.

The London Candidature File acknowledged the chronic need for affordable and social housing in East London, and indicated how the Athletes’ Village would be reconverted into a socially mixed development after the 2012 Olympic Games (London 2012, 2004). East Village had to compensate for the loss of 450 social housing tenancies in Stratford, caused by the demolition of the Clays Lane estate to make space for the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park and Athletes’ Village (Bernstock, 2014). The other reason for a high provision of social/affordable housing was the idea of compensating lower levels of these housing products in the plans for the other housing developments around the Park (ibid.). Dale Meredith (2012), the former managing director of Triathlon Homes, stated that ‘it is crucial that East Village residents encompass as broad a range of lifestyles, family sizes and life stages as possible’. Thus, nearly half (49 per cent) of the 2,818 East Village homes are ‘affordable’, while the remaining 51 per cent are private homes for rent (London 2012, 2004).

Ownership and governance of the Athletes’ Village properties and land – the rebranded East Village – is divided between two organisations: Qatari Diar Delancey (QDD) which owns and manages the private housing stock and also owns the freehold, and Triathlon Homes which owns and manages the affordable housing. Table 2 shows the East Village housing tenure pattern in 2018, although QDD subsequently received planning permission to develop 2,000 additional privately rented properties that are under construction (Interview, QDD manager).

The Triathlon Homes’ partners are two housing associations – East Thames and Southern Housing Group – and property developer First Base. In 2009, Triathlon Homes purchased the then Athletes’ Village 1,379 affordable housing units which comprised a mixture of social rent, intermediate rent, shared ownership and shared equity. In this case, intermediate rent means that 88 of these properties are let at 70 per cent of the market level, and 206 are let at 80 percent of the market level (Triathlon Homes, 2016, 2018). In 2011, Qatari Diar Delancey – a joint venture between Qatari Diar (the sovereign investment fund of the Qatari royal family) and British property developer Delancey – purchased the remaining 51 per cent of the East Village, together with the freehold. QDD has renamed the neighbourhood East Village, and has set up Get Living London (GLL) as their housing management arm (Bernstock, 2014; GLL, 2016). QDD’s properties are let on a private rental basis.

Several existing studies discuss various policy and sociological aspects of the East Village. For example, Humphry (2017) queries the notion of East Village as forming a cohesive and inclusive community, while Cohen (2017) analyses emergent tensions between social tenants and other residents. Humphry (2020) examines Triathlon Homes’ social housing allocation policies and practices. Our paper advances on these existing studies by drawing upon a broader evidence base (including survey research), but also one which has been collected in the later period when East Village was fully occupied and hence at the stage when the full implications of social mixing and affordable housing policies have become clearer. Watt and Bernstock (2017) and Bernstock (2020) have outlined how a socio-spatial distinctiveness between ‘Old and New Stratford’ has been created out of the various regeneration programmes, with Old Stratford being the un-regenerated area dominated by the existing multi-ethnic, working-class population, and the affluent New Stratford comprising regenerated areas including East Village. In the rest of this paper, we interrogate socio-spatial inequalities in Newham, including this emergent Old/New Stratford segregation, with reference to East Village and also how such inequalities are perceived and experienced by middle-class East Village residents.

Class, ethnic and age profile of East Village, Stratford and Newham

This section examines to what extent the East Village is socio-demographically similar or different from surrounding East London areas. It does so by comparing the 2017 EVS data on occupational class, ethnic background and age with equivalent 2011 Census data for both the Stratford and New Town ward and the borough of Newham (albeit with the caveat that there is a six-year gap between the Census and EVS).

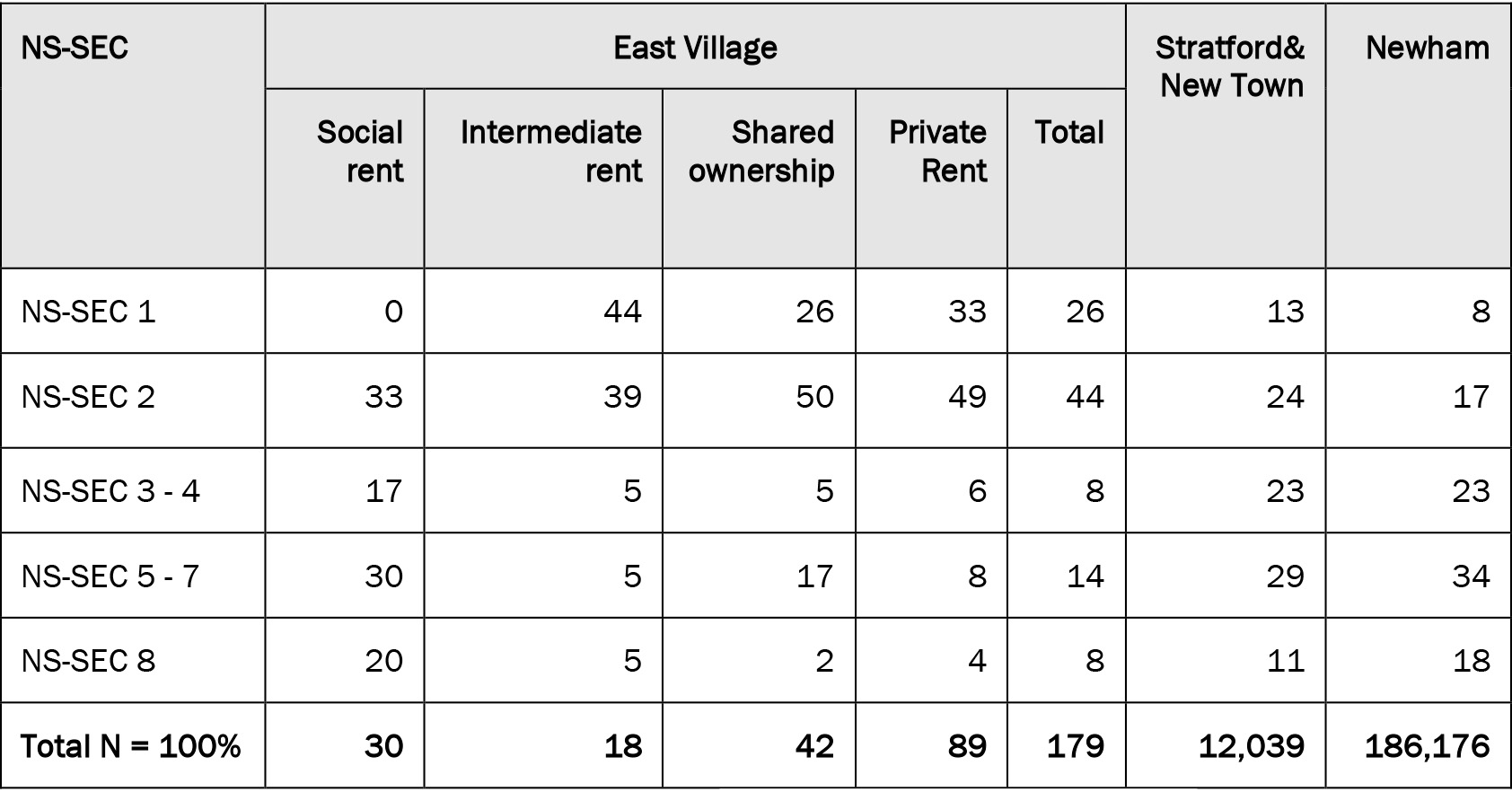

Table 3 summarises EVS respondents’ occupational class using the National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification [NS-SEC] and compares this to Stratford and New Town Ward, as well as Newham as a whole. NS-SECs 1 and 2 (higher and lower managerial and professional occupations respectively) form the ‘salariat’ or ‘service class’ and are ‘clearly middle class’ (Savage, 2015: 44). It is also this professional-managerial salariat/service class which is typically identified with gentrification in London (Hamnett, 2021; Yee and Dennett, 2021). However, one distinctive feature of London’s widening inequality is how the city functions as the premier location for what Cunningham and Savage (2017) refer to as the ‘elite’ section within the service class, that is the higher professionals and managers in NS-SEC 1 with the most economic capital. For this reason, we have separated NS-SEC 1 from NS-SEC 2 in Table 3. We have grouped the remaining occupational NS-SECs into two: an intermediate class of NS-SEC 3 and 4 (administrative and own-account occupations); and a routine/manual class of NS-SECs 5, 6 and 7 (technical, semi-routine and routine occupations). In addition, Table 3 includes NS-SEC 8 consisting of the never worked and long-term unemployed (after long-term unemployed), although we omit full-time students.

Taking NS-SEC 1 and 2 together, Table 3 shows that 70 per cent of EVS respondents were in the professional-managerial salariat compared to 37 per cent in Stratford and New Town and just 25 per cent of Newham residents. The equivalent figures for NS-SEC 1 indicate even wider relative differentials at 26 per cent, 13 per cent and 8 per cent respectively. Such findings demonstrate the distinctive and dominant affluent middle-class presence in East Village compared to surrounding areas, and highlight its gentrified character. By contrast, routine/manual occupations (NS-SEC 5-7) comprise just 14 per cent in the East Village compared to over twice that in both Stratford (29 per cent) and Newham (34 per cent). The long-term unemployed comprise 8 per cent of the EVS compared to 11 per cent in Stratford and 18 per cent in Newham. The East Village therefore contains a much smaller proportion of the most disadvantaged NS-SECs than either Stratford or Newham.

Turning to tenure divisions within East Village, three findings emerge. First, is that social renting is a sharp outlier tenure. Not only is it the only tenure with a minority (33 per cent) salariat population, but half of social renters are from the two lowest NS-SEC clusters (5-7 and 8) compared to 19 per cent for shared owners, 12 per cent for private renters, and just ten per cent for intermediate renters. Second, that the NS-SEC profile for the EVS social renters is much closer to the overall profiles for both Stratford/New Town and Newham.

Third, and most striking from the sociological perspective of understanding affordable housing, is that not only is the market-cost private rental sector (PRS) numerically dominated by the professional-managerial salariat (82 per cent), but so are the two intermediate ‘affordable’ tenures – intermediate rent (83 per cent) and shared ownership (76 per cent). In fact, nearly half (44 per cent) of intermediate renters are from the elite NS-SEC 1 (higher professionals and managers), even higher than the 33 per cent in the PRS. Therefore, the supposedly ‘affordable’ intermediate rent and shared ownership tenures are occupied by the same privileged class niche as private renting, which also contributes towards the deficient nature of social mixing strategies in the neighbourhood. The entry criteria mean that East Village intermediate renters and shared owners must be employed, their housing costs cannot make up more than 45 per cent of their net income, and they can have a gross household income of up to £90,000 per annum (Triathlon Homes, 2013, 2016; UK Government, 2018). This income cap is high, such that even some households in the most affluent 10 per cent of the London population could fit (Trust for London, 2017). Shelter (2013: 8) estimates that an intermediate rental East Village 1-bedroom flat set at 80 per cent of the market rental rate equates to 52 per cent, 46 per cent and 41 per cent of median wages in Hackney, Newham and Tower Hamlets respectively.

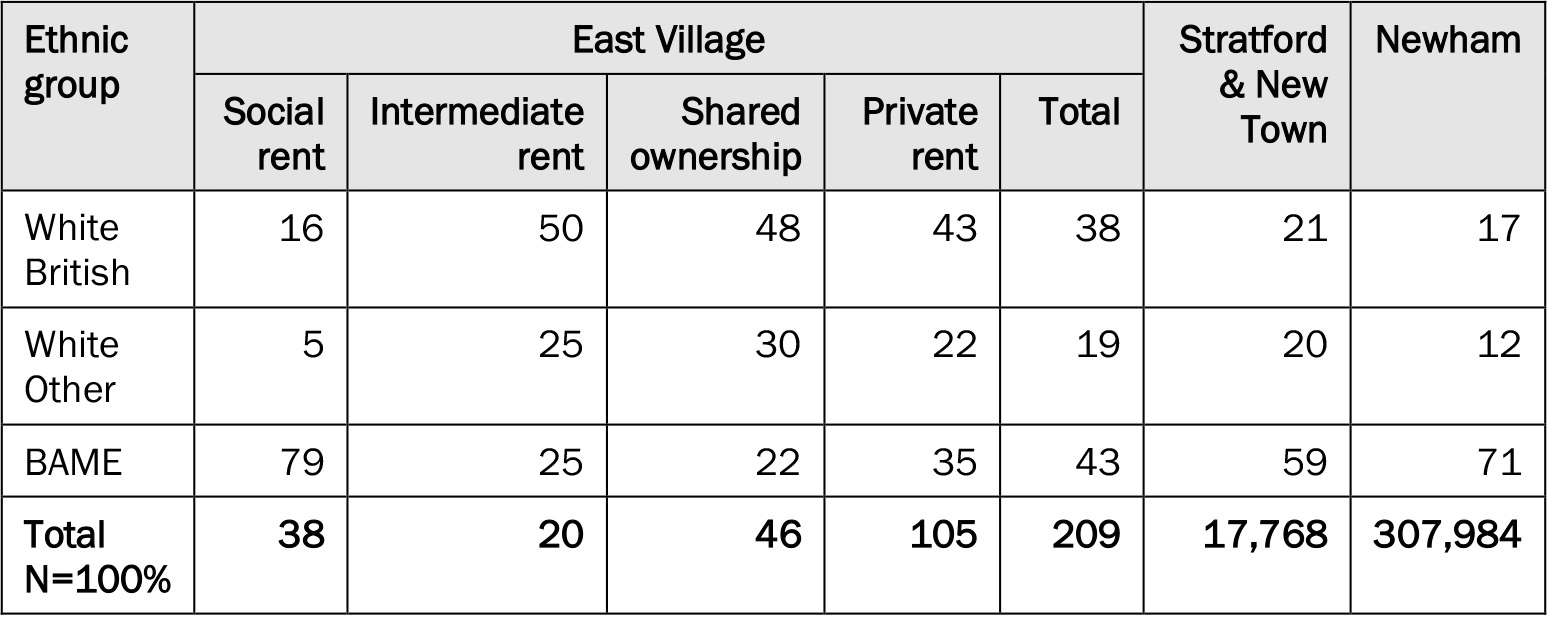

According to the 2011 Census, Newham is the most ethnically diverse local authority in the UK with the largest BAME population (71 per cent) and the lowest proportion of white British (17 per cent), with the remainder white Other (12 per cent). As Table 4 shows, Stratford and New Town is somewhat less ethnically diverse than Newham as a whole since 59 per cent of the population are from BAME backgrounds, 21 per cent are white British and 20 per cent white Other. However, as with social class, East Village has a distinct ethnic profile compared to both Stratford and Newham since it has a majority white population (38 per cent white British and 19 per cent white Other) and much smaller BAME population at 43 per cent.

Tenure is, however, highly significant for ethnicity. As with occupational class, the clear outlier tenure within East Village is social renting which has an ethnic profile much closer to the Newham average, since 79 per cent of social tenants are from BAME backgrounds, while only 16 per cent are white British and five percent are white Other. By comparison, the combined white British and white Other groups form the majority within private renting (65 per cent), but also in two other affordable tenures (78 per cent in shared ownership and 75 per cent in intermediate rent). Concomitantly, BAME residents form minorities in shared ownership (22 per cent) and intermediate rent (25 per cent), as well as the PRS (35 per cent). The fact that these two nominal ‘affordable’ tenures have a larger proportion of white residents than private renting suggests that their capacity to attract privileged households has a pronounced racialised/ethnic as well as class dimension.

So far, we have identified East Village as a gentrified, majority white enclave within a deprived multi-ethnic borough. However, as Barwick (2018) argues, the debate on social mixing tends to mis-represent ethnic minorities as forming a homogeneous disadvantaged group. By contrast, our analysis shows that while the white British and white Other groups combined account for 68 per cent of NS-SEC 1 and 2, just under one third are from BAME backgrounds. Therefore, there is a significant BAME presence among professional-managerial East Village residents.

In terms of age, the EVS sample is more youthful than both the Stratford and Newham populations. Ninety per cent of EVS respondents were aged between 18-44 including 23 per cent aged 18-24. This compares to 76 and 20 per cent respectively in Stratford and New Town, and 69 and 18 per cent respectively in Newham (2011 Census). However, private renters were the most youthful tenure within East Village since 33 per cent of these were aged 18-24, compared to just 10 per cent for both social and intermediate renters, and 17 per cent for shared owners. At the elderly end of the age scale, only one person (a mere 0.5 per cent) in the EVS sample was aged 65 and over compared to seven per cent in Stratford and nine per cent in Newham.

To conclude this section, we have established the distinctive socio-demographic profile of East Village. It has a much more substantial professional-managerial salariat presence, as well as larger white and youthful population than Stratford and New Town and even more so compared to Newham, a deprived multi-ethnic borough. However, the social class and ethnic backgrounds of the two East Village intermediate affordable tenures (shared ownership and intermediate renting) are far more closely aligned to the PRS than social renting. Social tenants are the distinct outlier tenure within the East Village since they have the most disadvantaged occupational class profile and also the largest BAME population proportion. In the following two sections, we focus on the socio-spatial perceptions and experiences of those professional and managerial interviewees who comprise the dominant class group within the residential field of the East Village but also within the surrounding Stratford area.

Territorial stigmatisation – the ‘rest of Stratford’

In this and the following section, we draw on interview data from 26 salariat/service-class interviewees living in those three tenures – PRS (7), intermediate renting (8) and shared ownership (11) – which, as highlighted above, share very similar occupational class profiles. Of these, 20 were either white British or white Other and the remaining six had BAME backgrounds. We discuss two socio-spatial ‘othering’ processes that this dominant class articulates and mobilises in order to distinguish themselves from spatially proximate subordinate groups. This section examines how ‘external othering’ occurs involving territorial stigmatisation directed against the ‘rest of Stratford’, while the following section analyses the ‘internal othering’ process based upon housing tenure stigmatisation directed against social renters within East Village itself.

We established above how a socio-spatial divide exists between the predominantly gentrified East Village neighbourhood and the nearby surrounding poorer and more ethnically diverse ‘rest of Stratford’. Class and ethnic socio-spatial differences between East Village and the surrounding area emerged in the interviews with professionals and managers vis-à-vis the commonplace notion that Stratford contains two distinct ’sides’ or ‘worlds’.

Stratford as a whole is like two worlds, you’ve got this side and then you’ve got the other side and it’s completely different. The population, there’s a lot of ethnic minorities and Eastern Europeans on the other side; and here I think there’s mainly white British young professionals. I found maybe some immigrants but not as many as on the other side, so yeah it’s completely different! (Alexander, 27, male, white British, NS-SEC 1, intermediate renter)

Interviewees described how they were living in a ‘bubble’ which was, according to Alan, explicitly ‘gentrified’ and also ‘really nice’.

East Village is a bubble, really nice, gentrified, a lot of investments, really nice shops, the flats are really nice. It’s a bubble, completely different from Stratford and the rest of East London. It’s a really nice bubble! (Alan, 27, male, white British, NS-SEC 1, leaseholder)

Butler (2003) identified living in a ‘bubble’ as a prominent place image among white, affluent gentrifiers in the North London Borough of Islington who live in close spatial proximity with diversity but have very limited social contact with it. In contrast to the positive appreciation of their immediate environment within the East Village itself – living in a bubble – mixophobic feelings (Bauman, 2013) were commonly expressed regarding the lower-class, ethnically diverse ‘rest of Stratford’ which was outside of and set apart from East Village.

I think there is a real divide between what is now being built out of the East Village. It’s kind of like a bubble around everywhere else. Because I think there’s a lot of poverty that we don’t see until we leave this East Village bubble. Here is where posh people live, if you want to put it that way, and then there is the rest of Stratford, that it’s old and it’s not very nice to live in. I think there is a very clear divide between this is the new and this is the old. This is where you know people with a bit more money can afford, and that is where people who don’t have that much money can go to live (Jade, 27, female, white Canadian, NS-SEC 2, intermediate renter).

Hence, the first ‘othering’ process consists of widespread negative reactions by middle-class East Villagers towards this other ‘not very nice’ space – in other words, territorial stigmatisation (Horgan, 2020). Such stigmatisation emerged in interviewees’ accounts of the 1970s’ built Stratford Centre shopping mall located in the ‘rest of Stratford’. This mall, which is directly opposite the more recent and much larger, upmarket Stratford Westfield mega-mall, provides low-cost, ethnically diverse shops and market stalls and is well-used by Stratford and Newham residents including as a hang-out for local multi-ethnic youth (Kennelly, 2016). However, it is a place that held little appeal for professional-managerial East Village residents who either avoided it or went there warily.

There’s not much going on in the rest of Stratford, and I’m not sure what the ownership is but I don’t know why the old Stratford Centre… I don’t know why it’s still there. It’s just… It’s ugly! There’s nothing good happens in there. I don’t know why it’s still there to be honest. But maybe people just refuse to develop it. I don’t know but I just never go there. I just live in the new stuff. There’s nothing going on in Stratford to be honest (Jack, 39, male, white British, NS-SEC 2, private renter).

If Jack avoided the Stratford Centre because it contained nothing of value as far as he was concerned, others went there but described the users of this space in mixophobic terms. The Stratford Centre has a public right of way through it so it is not locked during the night. Due to the worsening homelessness situation in Newham, this mall has provided a nightly safe space for the borough’s burgeoning population of rough sleepers (BBC News, 2018). Stephen illustrates how the Stratford Centre ‘feels very East London’ with its anxiety-provoking ‘sketchy’ people.

The old Stratford Centre on the other side of Stratford it feels very East London. Maybe it’s because buildings are older, and if you walk through Stratford Centre at night, there’s a lot of people who are sleeping rough in there. And that makes me feel aware… Not in danger but that I have to be aware of my personal safety a bit more because there is a real risk that I might be robbed or something like that. You know the feeling when there is a lot of people who don’t have a lot around me… There’s a few people around that look a bit sketchy, some people obviously on drugs (Stephen, 39, male, white Australian, NS-SEC 1, private renter).

The East London symbolic otherness of the ‘rest of Stratford’ stands in stark binary contrast to the privileged enclave-feel of the East Village which is geographically located within East London, but socially set apart. This othering is evident in the quote below, where the expression ‘Olympic Village’ is used to reinforce the socio-spatial boundaries between the East Village and the surrounding abject spaces that have not yet been ‘cleaned up’ aka regenerated (Campkin, 2013).

It’s a bit rough when you walk out of the Olympic Village towards the other side. The canals on that side [Hackney Wick], that feels a bit less safe. It’s probably because they are not as well cleaned up I guess, and it’s probably the same in Stratford. I only go to Stratford if I need to go to the post office in the Stratford Centre (Antonella, 29, female, white British, NS-SEC 2, intermediate renter).

Mixophobic anxieties about visible deprivation and diversity characterise affluent East Villagers’ accounts of leaving their ‘bubble’ to venture into the ‘urban badlands’ in the other Stratford. These feelings reflect the East Villagers’ selective belonging (Watt, 2009) – a strong positive place attachment to their immediate neighbourhood dominated by ‘people like them’, combined with a sense of discomfort predicated on the lack of ‘fit’ between their privileged middle-class habitus within the working-class, multi-ethnic space of the rest of Stratford. However, not all East Village professional-managerial interviewees expressed such a lack of fit. Linda, for example, worked in Stratford and had developed a familiarity with it, which meant she did not share the same anxieties as her neighbours. Nevertheless, she acknowledged the socio-spatial separation between East Village and the rest of Stratford.

I think it’s got quite a different feel to East Village, it does feel quite separated in many ways which is a shame because that should be part of Stratford rather than being a separate place. It does feel that there is one side of the railway track and another side of the railway track (Linda, 27, female, Asian, NS-SEC 2, leaseholder).

Tenure stigmatisation – social renters

The second othering process is based upon housing tenure and consists of negative reactions towards social renters within East Village. Such tenure stigmatisation regarding social renters is widespread (Horgan, 2020; Watt, 2021), and a Triathlon Homes manager acknowledged its presence at East Village (see also Cohen, 2017):

We have a problem in our society, that we tend to want to hate poor people, and I see evidence of that on the Village. So one of the things I have to deal with is a lot of overt and sometime covert criticism of the social renters and that’s a struggle.

Among the middle-class interviewees, tenure stigmatisation was prominent among shared owners most of whom explicitly criticised the behaviour of social renters. These two groups of residents were often physically proximate since they lived in the same blocks of flats, albeit on different floors with the social renters typically occupying the lower floors – an example of ‘vertical micro-segregation’ (Maloutas and Botton, 2021). The shared owners tended to attribute anti-social behaviour – in the form of noise, littering in the communal areas, and drug usage – to the presence of social renters.

There was a group of people in my block who were that sort of behaviour. They didn’t fit in. I think they got kicked out in the end. They were smoking inside and putting cigarettes out on the carpet and leaving drinks in the lift, and to a degree I saw drug dealers coming to the buildings. I don’t really know what the make-up in my building is, but if you have got affordable or some other type of affordable rent, or people who don’t care, that’s what you’re gonna get (Thomas, 36, Male, white South-African, NS-SEC 1, shared owner).

One noteworthy aspect of this quotation is that while shared owners are officially affordable housing residents themselves, Thomas did not self-identify as such. Instead, the ‘affordable’ people were those ‘others’ who engage in anti-social behaviour. Bretherton and Pleace (2011) have also shown how shared owners tend to disavow their own affordable housing status and instead stigmatise social renters as not being ‘like them’. In effect, the social renters’ presence within East Village is questioned; they are considered a deviant, abject lower-class and racialised ‘other’ (Sibley, 1995).

We have the people downstairs who are living in the council places. Not so much now, but at some points we had some disturbance at night, it’s just a problem which is down to socio-economic background. Some of them don’t really understand what area they are living in. Some of the things I’ve heard is some people from Eastern Europe for example who tend to have different sleeping habits, and that caused a problem. Some people who are living in council flats… I don’t have proof, but sometimes I was walking around the area and I was smelling weed (Marine, 32, female, white European, NS-SEC 1, shared owner).

The expression “don’t really understand what area they are living in” displays the inconsistency of the Olympic Legacy objective to deliver a genuinely socially mixed development. The lifestyles of ‘respectable’ middle-class residents are normalised, while certain minority ethnic ‘others’ are regarded as illegitimate within the area. While tenure stigmatisation by shared owners towards social renters was routine, it was not ubiquitous. Enrique and his partner, for example, felt like outsiders among what they considered the predominant socially conservative mind-set among the East Village shared owners who engaged in tenure-based stereotyping.

The comment [by shared owners] often has been ‘these social housing people’. They [shared owners] put a label. They consider that everybody living there is the same kind of person, to some level dehumanising this kind of people. Saying you know like grouping them all like kind of beasts! They don’t use the word ‘beasts’ but they say like ‘the social housing people’. They use the ‘they’, there is common use of ‘they’, like ‘they are all the same’. So my point is there have been minimal episodes of kind of not respecting the communal areas, and the response has been quite harsh from the other people that are shared owners (Enrique, 36, male, white European, NS-SEC 2, shared owner).

Helen, an intermediate renter who lived in a mixed-tenure block, also negatively associated the nearby presence of social housing with ‘noisy’ children in the courtyards.

If we want to sit outside, we’ll go to the Park or the canal. [The courtyard] is very noisy, there’s always kids playing there. Like the ground floor they are all social housing and they are very noisy. There’s about ten people living in each house. It’s very strange! (36, female, white British, NS-SEC 2)

Although tenure stigmatisation existed among the middle-class private and intermediate renting interviewees, on the whole this was less prominent among them compared to the shared owners. Indeed, many private and intermediate renters appeared to neutrally blank out the presence of social renters in the neighbourhood. Three factors help to explain this differential response. First is the micro-geography of housing tenure distribution whereby many PRS properties are located in separate mono-tenure blocks – horizontal micro-segregation – hence private tenants are simply less likely to have social renting neighbours compared to shared owners. The second factor is that while most of the private and intermediate renting interviewees enjoyed living in East Village and appreciated its amenities, they tended to have either non-existent or minimalistic interaction (saying ‘hello’ and taking in parcels) with neighbours living in the same blocks as themselves, for example:

I never see them! [the neighbours]. I never see them, I never hear them, but everyone I do come across in the Village is just very nice, […] but I don’t come across them very much. I’ve been here for 10 months and I’ve seen people on my floor less than 10 times. I just never see anyone, I don’t know why (Jack, 39, male, white British, NS-SEC 2, private renter).

To be honest I don’t see them [the neighbours] very often, you know just when you go down the lift and you might see them and say ‘hello’. Occasionally we might take a parcel for them or something like that, but we’re just so busy in our lonely world that we don’t really interact as much with our neighbours {Zara, 30, female, Asian, NS-SEC 2, intermediate renter).

Such limited neighbouring patterns are probably related to how the private and intermediate renters were more likely to have a shorter-term engagement with East Village compared to either the shared owners or social renters.

The third explanatory factor is how the shared owners have financially invested in their homes via property ownership unlike either the private or intermediate renters, and this was something that the Triathlon manager thought was significant.

So I would say there’s the social renters and then everybody else. If you are an intermediate renter, you are passing through. But the shared owners own part of their property, and therefore this is their investment, and they want their investment to be protected and to grow! So everything that jeopardises that…

Hence, the shared owners regarded the littering in the communal areas (blamed on social renters), as an issue that devalued their stake in their properties.

Conclusion

Although parts of Newham and especially Stratford are gentrifying, these remain predominantly multi-ethnic areas with a substantial working-class presence as well as extensive and intensive poverty, deprivation and housing disadvantage (Almeida, 2021; Gillespie et al., 2021; Watt, 2020, 2021; Yee and Dennett, 2021). As White (2020: 120) notes, ‘Newham may have pockets of gentrification, but it is still a poor borough’. Despite the policy hype surrounding mixed-tenure and affordable housing provision in post-Olympics East London, this paper has employed quantitative and qualitative data to reveal how East Village is one such pocket or ‘bubble’ of gentrification in Newham. The mixed-tenure East Village is a majority white, young/middle-aged neighbourhood, one that is dominated by a professional-managerial salariat – the class which is most associated with gentrification (Hamnett, 2021). Not only is East Village a gentrified neighbourhood, it is even a residential site for potential ‘elite formation’ (Cunningham and Savage, 2017) within East London given its high proportion of higher professionals and managers in NS-SEC 1.

We have shown how the majority of privately rented East Village properties are occupied by professionals and managers who can afford the expensive rents, but also how this same salariat/service class predominates in the two intermediate affordable tenures – shared ownership and intermediate renting. By contrast, social renting is the clear outlier tenure within East Village given how its occupational and ethnic profiles are sharply differentiated from the other three tenures and are also much closer to the Newham, and Stratford and New Town averages.

The interview data illustrate processes of selective belonging (Watt, 2009) whereby the middle-class East Village residents living in private renting, intermediate renting and shared ownership regard their neighbourhood as a socially distinct, privileged ‘bubble’ surrounded by a deprived and ethnically diverse area. As such, we identified two class and racialised othering processes. First, professional-managerial residents display a mixophobic (Bauman, 2013) reaction encompassing feelings of discomfort and anxiety towards an ‘external other – ’the ‘rest of Stratford’ – a territorially stigmatised place that they either avoided or visited warily. Secondly, East Village social renters – whose class and ethnic backgrounds are most similar to Stratford and Newham residents – are seen as an ‘internal other’ and especially by shared owners who stigmatise social renters as being ‘unlike them’ despite the fact that both tenures have an official ‘affordable’ status (Bretherton and Pleace, 2011). Therefore, not only is shared ownership a de facto gentrified tenure since it’s primarily occupied by the professional-managerial salariat, but this privileged class also engages in socio-spatial exclusionary practices regarding proximate social renters within the East Village residential field. In general, the socio-spatial distinction of those inhabiting a middle-class habitus is emphasised vis-à-vis both internal and external class and racialised ‘othering’ (Davidson, 2010).

Much of the so-called ‘affordable housing’ in East Village is occupied by affluent middle-class professionals and managers who are not in the desperate housing need that far too many Newham residents – and especially those from BAME backgrounds – experience (Thompson et al., 2017; Watt, 2020; Gillespie et al., 2021). The social mixing which East Village supposedly represents conceals socio-spatial segregation patterns and processes operating at two spatial scales. First, segregation between East Village – part of the regenerated and gentrified ‘New Stratford’ – and the spatially proximate but socially distant ‘rest of Stratford’ aka the working-class and multi-ethnic ‘Old Stratford’. Second, ‘micro-segregation mechanisms and processes’ (Maloutas and Botton, 2021: 2) which occur within East Village in relation to housing tenure in both vertical and horizontal forms. Not only do our findings reinforce widespread academic scepticism regarding the efficacy of mixed-tenure neighbourhoods in general (Tunstall and Lupton, 2010; Levin et al., 2022), they also highlight how the Olympics’ ‘inclusive’ legacy and social mixing goals are far from being realised in practice (see Cohen, 2017; Humphry, 2020; Bernstock, 2020). In conclusion, this paper has highlighted how the twin policy pillars of the East Village promotional lexicon – affordable housing and social mixing – provide an ideological gloss on a reality involving profound socio-spatial inequalities and segregations.

Piero Corcillo and Paul Watt, Department of Geography, Birkbeck University of London, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HX. England. Email: pcorci01@mail.bbk.c.uk / p.watt@bbk.ac.uk

Almeida, A. (2021) Pushed to the margins: Gentrification in London in the 2010s. London: Runnymede Trust.

Barwick, C. (2018) Social mix revisited: within- and across-neighbourhood ties between ethnic minorities of differing socioeconomic backgrounds. Urban Geography, 39, 916-934. CrossRef link

Bauman, Z. (2013) Liquid modernity. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

BBC News (2018) Stratford shopping centre shelters dozens of homeless, BBC News. [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-england-london-44551135 [Accessed: 11/04/2022].

Bernstock, P. (2014) Olympic housing. A critical review of London 2012’s legacy. Farnham: Ashgate.

Bernstock, P. (2020) Evaluating the contribution of planning gain to an inclusive housing legacy: a case study of London 2012. Planning Perspectives, 35, 927-953. CrossRef link

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction. London: Routledge.

Bretherton, J. and Pleace, N. (2011) A difficult mix: issues in achieving socioeconomic diversity in deprived UK neighbourhoods. Urban Studies, 48, 3433-3447. CrossRef link

Butler, T. (2003) Living in the bubble: gentrification and its ‘others’ in north London. Urban Studies, 40, 2469-2486. CrossRef link

Campkin, B. (2013) Regenerating London: Decline and regeneration in urban culture. London: I.B. Tauris. CrossRef link

Cohen, P. (2017) A place beyond belief: hysterical materialism and the making of East 20. In: Cohen, P. and Watt, P. (eds) London 2012 and the post-Olympics city: A hollow legacy? London: Palgrave Macmillan, 139-177. CrossRef link

Corcillo, P. (2021) Social mixing and the London East Village: Exclusion, habitus and belonging in a post-Olympics neighbourhood. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Birkbeck, University of London.

Cunningham, N. and Savage, M. (2017) An intensifying and elite city. City, 21, 25-46. CrossRef link

Davidson, M. (2010) Love my neighbour? Social mix in the London gentrification frontier. Environment and Planning A, 42, 525-544. CrossRef link

DWP [Department for Work and Pensions] (2020) Children in low income families – local area statistics, 2014 to 2019. DWP. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/children-in-low-income-families-local-area-statistics-201415-to-201819 [Accessed: 04/04/2022].

Elahi, F. and Khan, O. (2016) Ethnic inequalities in London. London: Runnymede Trust.

Foster, J. (1999) Docklands: Cultures in conflict, worlds in collision. London: UCL Press.

Fransham, M. (2017) Changing deprivation in East London. University of Oxford. Available at: https://www.geog.ox.ac.uk/news/articles/170320-changing-deprivation.html [Accessed: 07/04/2022].

Gillespie, T., Hardy, K. and Watt, P. (2021) Surplus to the city: austerity urbanism, displacement and ‘letting die’. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 1-17. CrossRef link

GLL [Get Living London] (2016) About Get Living London and East Village. Internal GLL document. Unpublished.

Hamnett, C. (2003) Unequal city: London in the global arena. London: Routledge. CrossRef link

Hamnett, C. (2021) Veni, vidi, gentri? Social class change in London and Paris: gentrification cause or consequence? Urban Geography, 42, 1045-1053. CrossRef link

Hanna, K. and Bosetti, N. (2015) Inside out: The new geography of poverty and wealth in London. London: Centre for London.

Horgan, M. (2020) Housing stigmatization: a general theory. Social Inclusion, 8, 8-19. CrossRef link

Humphry, D. (2017) ‘The best new place to live’? Visual research with residents in East Village and E20. In: Cohen, P. and Watt, P. (eds) London 2012 and the post-Olympics city: A hollow legacy? London: Palgrave Macmillan, 179-204. CrossRef link

Humphry, D. (2020) From residualisation to individualization? Social tenants’ experiences in post-Olympics East Village. Housing, Theory and Society, 37, 458-480. CrossRef link

Keddie, J. and Tonkiss, F. (2010) The market and the plan: housing, urban renewal and socio-economic change in London. City, Culture and Society, 1, 57-67. CrossRef link

Kennelly J. (2016) Olympic exclusions: Youth, poverty and social legacies. London & New York: Routledge. CrossRef link

Levin, I., Santiago, A.M. and Arthurson, K. (2022) Creating mixed communities through housing policies: global perspectives. Journal of Urban Affairs, 44, 291-304. CrossRef link

Lindsay, J. (2008) Measuring the persistence of poverty in East London. Information, Society and Justice, 2, 37-45.

Lindsey, I. (2012) Social mixing: a life in fear. Urbanities, 2, 25-44. CrossRef link

London 2012 (2004) London candidature file. London 2012 bidding team. Available at: https://library.olympics.com/Default/doc/SYRACUSE/28313/london-2012-candidate-city-dossier-de-candidature-london-2012-candidate-city-candidature-file-comite [Accessed: 12/04/2022].

Maloutas, T. and Botton, H. (2021) Vertical micro-segregation: is living in disadvantageous lower floors in Athens’ apartment blocks producing negative social effects? Housing Studies. CrossRef link

MHCLG [Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government] (2015) English Indices of Deprivation 2015. MHCLG. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2015 [Accessed: 04/04/2022].

Meredith, D. (2012) The Olympic Legacy, creating a new community for London in Stratford. The Guardian, [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/housing-network/2012/jul/19/olympic-legacy-social-housing-east-village [Accessed: 14/05/2022].

Preece, J., Hickman, P. and Pattison, B. (2020) The affordability of ‘affordable’ housing in England: conditionality and exclusion in a context of welfare reform. Housing Studies, 35, 1214-1238. CrossRef link

Raval, A. (2021) Inside the ‘Covid Triangle’: a catastrophe year in the making. FT Magazine, [online] Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/0e63541a-8b6d-4bec-8b59-b391bf44a492 [Accessed: 01/04/2022].

Sagoe, C., Weekes, T. and Stratton, E. (2020) A capital in crisis. London: Shelter.

Savage, M. (2011) The lost urban sociology of Pierre Bourdieu. In: Bridge, G. and Watson, S. (eds) The New Blackwell companion to the city. Malden, MA: Wiley- Blackwell, 511-520. CrossRef link

Savage, M. (2015) Social class in the 21st century. London: Penguin. CrossRef link

Shelter (2013) When the golden dust settles: Housing in Hackney, Newham and Tower Hamlets after the Olympic Games. London: Shelter.

Shi, Q. and Dorling, D. (2020) Growing socio-spatial inequality in neo-liberal times? Comparing Beijing and London. Applied Geography. 115. CrossRef link

Sibley, D. (1995) Geographies of exclusion. London: Routledge.

Smith, T., Noble, M., Noble, S., Wright, G., McLennan, D. and Plunkett, E. (2015) The English Indices of Deprivation 2015: Research report. London: Department for Communities and Local Government.

Thompson C., Lewis D. J., Greenhalgh T., Smith N. R., Fahy A. E. and Cummins S. (2017) ‘I don’t know how I’m still standing’: a Bakhtinian analysis of social housing and health narratives in East London. Social Science & Medicine, 177, 27-34. CrossRef link

Triathlon Homes (2013) Shared Ownership, Shared Equity and Intermediate Market Rent Allocation Policy. Internal Triathlon Homes document. Unpublished.

Triathlon Homes (2016) Intermediate market rent re-let Policy. Internal Triathlon Homes document. Unpublished.

Triathlon Homes (2018) Triathlon Homes tenures breakdown. Internal Triathlon Homes document. Unpublished.

Tunstall, R. and Lupton, R. (2010) Mixed communities: Evidence review. London: DCLG.

UK Government (2018) Affordable home ownership scheme. UK Government. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/affordable-home-ownership-schemes [Accessed: 14/05/2021].

Vadiati, N. (2020) The employment legacy of the 2012 Olympic Games: A case study of East London. Singapore: Palgrave Pivot. CrossRef link

Watt, P. (2009) Living in an oasis: middle-class disaffiliation and selective belonging in an English suburb. Environment and Planning A, 41, 2874-2892. CrossRef link

Watt, P. (2013) ‘It’s not for us’: regeneration, the 2012 Olympics and the gentrification of East London. City, 17, 99-118. CrossRef link

Watt, P. (2020) ‘Press-ganged’ generation rent: youth homelessness, precarity and poverty in East London. People, Place and Policy, 14, 128-141. CrossRef link

Watt, P. (2021) Estate regeneration and its discontents: Public housing, place and inequality in London. Bristol: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Watt, P. and Bernstock, P. (2017) Legacy for whom? Housing in post-Olympic East London. In Cohen, P. and Watt, P. (eds), London 2012 and the Post-Olympics city: A hollow legacy? London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 91-138. CrossRef link

White, J. (2020) Terraformed: Young black lives in the inner city. London: Repeater Books.

Yee, J. and Dennett, A. (2021) Stratifying and predicting patterns of neighbourhood change and gentrification: An urban analytics approach. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 00, 1–21. CrossRef link