Abstract

Tens of thousands of women and children are forced to relocate in the UK to escape domestic violence in a mass of individual and hidden journeys. As Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the UK, the state should have duties to minimise their losses, and support their resettlement; but such duties are not currently acknowledged at either local or national scale. The scale of government is crucial in understanding – and potentially addressing – this failure; and the gendered and spatial inequalities that result. Domestic violence services – such as women’s refuges – are generally provided at the scale of local government; whereas women commonly cross administrative boundaries to seek help. Women who stay put, remain local or go elsewhere as part of their help-seeking strategies need different types of services; highlighting the service infrastructure that should be developed to address their rights and needs. This article presents analysis of administrative data from services – over 180,000 records of service access by women in England over 8 years – highlighting the patterns of flows between local authorities and within regions; and concluding with the inappropriateness of focusing service responses on the local authority scale. It uses this evidence to argue for policy and practice changes that could journeyscape the current service landscape to ensure a more effective response, based on the rights and needs of women and children. An overview of Part 4 of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 is presented to indicate how it fails to address the regional and national scale of women’s domestic violence journeys.

Introduction

Violence against women is internationally recognised as a human rights violation (UN CEDAW Committee, 2017), meaning that any individual help-seeking due to abuse, and any state or community responses to such help-seeking must be considered within a human rights framing. This article focuses on a particular aspect of violence against women – abuse within adult interpersonal relationships, which may be termed domestic violence or domestic abuse – and a particular form of help-seeking: geographical relocation. Such relocation is common, involving tens of thousands of women and children in the UK every year, but continues to be under-recognised in research, policy, law, and practice. Because the relocation is forced by the human rights violation of violence against women, the individuals should be recognised as Internally Displaced Persons (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 1999; 2004), placing duties on the state to minimise their losses and support their resettlement, including via sufficient service provision, such as women’s refuges/shelters (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2017). Not only is this rights-based framing not recognised in UK law and policy, the state responses in terms of services and funding continue to be fragmented and insufficient (Imkaan, 2018; Women’s Aid, 2021). Both internationally, and within the nations of the UK, there are inconsistent responses, varying over time and place, rather than a sustained infrastructure of support that addresses both individual needs and structural inequalities and rights.

The focus of this article is domestic violence journeys – geographical relocations forced by the abuse and by seeking help, support, and resettlement – but that is not intended to imply that it is the ideal or only strategy of help-seeking. Many women and children stay put and seek help; and some are able to stay physically and emotionally safe because of action taken against the perpetrator. This clearly should be their right. However, the current situation in the UK, as in most states, is that perpetrators are not sufficiently held to account to stop the threat they cause (Ofsted et al., 2017; Coy and Kelly, 2019); and many women – entirely rationally – do not use statutory processes because they know that they will not work. It is important to note that this also renders them invisible to the key data sources used for needs assessments and decisions on service provision (ONS, 2020). However, relocation is currently a strategy pursued by tens of thousands of women and children, and therefore argued here to be a key concern for policy and practice responses. At every stage of women’s domestic violence journeys there is an interplay between force and agency (Bowstead, 2017a): the language of ‘help-seeking strategies’ is not intended to imply that women have unfettered options and the freedom to plan complex strategies, but that they have degrees of agency within the constraints of the force from the abuser and the limited options of service provision and eligibility. From a rights-based framing, policy and law should enable individuals’ rights to a violence-free life, and to minimise the losses and harms of abuse. Domestic violence journeys within the UK should not be forced or constrained by the state, in the same way that they should not be forced or constrained by the abuser. Women and children should be enabled to journey as far as they need, and stay as near as they can: the concept of ‘journeyscapes’ (Bowstead, 2018b), and the role of the state should be to journeyscape an otherwise potentially hostile terrain. It is not for the state to determine whether or not abused women and children journey; but it is a duty of the state to respond appropriately with law, policy, and provision to enable – to journeyscape – any journeys that are made.

The extent and scale of domestic violence journeys are striking (Bowstead, 2015a), and raise key issues to be explored in this article about the intersection between the scale of government and the scale of needs. Needs may be expressed locally but it is a mistake to think they are necessarily generated locally – or that the solutions or responses can or should be locally restricted or boundaried. Responses to domestic abuse include service provision, both specialist such as women’s refuges, and more generic accommodation and support services. This complex range of provision varies from place to place (Coy et al., 2009, 2011; Women’s Aid, 2021), not least due to the competitive context of service funding and provision; between service providers and between local authorities, especially neighbouring ones. Increasing devolution of responsibilities to the local authority scale in England, especially since the Localism Act of 2011 (DCLG, 2011), has not always been accompanied by appropriate resources or by evidence that such duties can be effectively discharged at such a local scale (LGA, 2020). A combination of competition and marketisation of service provision has resulted in a simultaneous up-scaling and down-scaling of governance (Swyngedouw, 2005) so that at the local level service provision may be commissioned locally but contracts are awarded to less-local large-scale providers. Local commissioning processes create greater local differentiation, at the same time as it can be politically expedient to bemoan a ‘postcode lottery’ (DAC, 2021). It is clear that the geographical scale of service provision is often not evidence-based, in terms of what is properly local and at what scale (Clarke, 2013; Gore, 2018). National Government currently only provides guidance to support local commissioning (Home Office, 2016) rather than justifying or evidencing why such commissioning should be only local in the first place. Cox argues that ‘the status quo in England is contriving to create the worst of both worlds: postcode lotteries at the local level and a centralised economy at the national level’(2014: 158).

Therefore, though domestic violence needs may be expressed by help-seeking in local places, it is not necessarily the case that localities can be assumed to be homogenous with ‘a commonality of interest and identity’ (Jacobs and Manzi, 2013: 38). In addition, it is necessary to understand what forces people to move into and out of localities – indicating that needs are generated socially rather than locally. Whilst domestic violence service provision is devolved to local authorities, for example, the welfare and benefits system is not devolved to local authorities (Parvin, 2009). Jacobs and Manzi therefore argue that ‘we can also raise the question as to what scale the “local” should operate’ (2013: 39). This article will address this question in terms of domestic violence journeys, using administrative data to analyse the scale of women’s help-seeking within local authority areas and across local authority boundaries; and therefore the scale at which rights and provision should operate. This article addresses women’s help-seeking, but notes that men do seek help due to domestic violence. Analysis of the administrative data indicates that women are in the vast majority, even more so in terms of relocating, and that men’s help-seeking strategies are significantly different (See Bowstead, 2018a for further details).

The methodology will be outlined in the next section, followed by the research analysis in terms of scale of help-seeking and scale of government, including the distinctive role of women’s refuges. Some implications for policy and provision of the mis-match between the different scales are then discussed, with some conclusions on the current situation of domestic abuse responses in England.

Methodology and limitations

The analysis presented in this article is based on a mixed methods research project, but the focus here is on the use of administrative data from the Supporting People Programme (ODPM, 2002), which included a wide range of accommodation and non-accommodation services from 2003-2011. The processing and use of such service monitoring data is discussed in detail in another article (Bowstead, 2019a), but the focus here is on the records of service access in England where the primary reason was women ‘at risk of domestic violence’. In terms of location/relocation, at the point of accessing service support women may ‘stay put’, ‘remain local’ (within the same local authority), or ‘go elsewhere’ (across a local authority boundary) (Bowstead, 2021a). For example, out of 25,557 cases of service access in 2010-11, 31 per cent stay put, 32 per cent remain local, and 37 per cent go elsewhere. Whilst the annual number of women and children staying put and accessing support increased over the years of data collection, the numbers relocating to access services did not correspondingly reduce; so this indicates the increasing provision of non-accommodation services addressed unmet need, rather than significantly reducing the need to relocate (Bowstead, 2021a). Similarly, local authorities with higher levels of service provision had higher rates of both remaining local and going elsewhere, indicating that local service provision enables different types of help-seeking, rather than simply preventing the need to relocate across local authority boundaries. A limitation of administrative data is that they record what happened but cannot indicate what an individual wanted to happen in terms of service access. However, they provide a large scale of evidence that would otherwise be unavailable: focusing here on when the individual had changed accommodation at the point of accessing the service, there is a consistent annual total of approximately 18,000 cases per year, with around 9,500 women (over half with children) migrating across local authority boundaries to access services (i.e. ‘go elsewhere’) and around 8,500 relocating within their local authority (i.e. ‘remain local’).

There are eight years of individual level data on service access, made available for research under Special Licence (DCLG and University of St Andrews, 2012), and just under four years of data on service exit. Such data are no longer available (Centre for Housing Research, 2015), not least due to commercial concerns in a competitive tendering context (Imkaan and Women’s Aid, 2014; Women’s Aid, 2021). Many of the services still exist, and will be generating monitoring data, though there have been significant funding cuts (Towers and Walby, 2012). However, the data are not being de-identified, aggregated and made available for research, making any comprehensive England-wide conclusions and plans harder than they were before 2011.

The data are therefore increasingly historic, but unusually comprehensive in being de-identified and at the individual scale; and including local authority locations. In addition, they provide evidence on individuals otherwise excluded from the statistics that often drive decision-making (ONS, 2020). These women on the move are automatically excluded from the sampling frame of social surveys, such as the Crime Survey, which only includes the population in households in settled accommodation but is widely used as a key data source on domestic abuse. In including a wide range of service provision – not just services designated for domestic violence support – the data also include far more nuances of what women did to access services, including in the absence of specialist domestic abuse provision. The data therefore reflect an aspect of demand, within constraints and limitations, and therefore reveal a lot more than has been evidenced before about women’s domestic violence help-seeking. As well as datasets from service access and exit, a linked dataset was created across service access and exit for the same individuals. The linked dataset therefore records the three local authority locations (before, during and after) for each individual service access, identifying whether there was relocation and/or internal migration between local authorities at each stage, Many women and children may have multi-stage journeys (Bowstead, 2017b, 2017a), but such geocoding analysis does indicate the journeys associated with each service access, and enables aggregation into flow maps and diagrams at different scales, as discussed in the next section.

Scale of help-seeking, scale of Government

Previous publications from this research have highlighted women’s three help-seeking strategies in terms of place: stay put, remain local and go elsewhere; and the different characteristics of people, place, provision and referrals that might make different strategies more likely (Bowstead, 2021a). However, in terms of England, the Government continues to devolve duties to the local authority scale of government. In terms of the most recent focus on responses to domestic abuse, the Government places duties on Tier 1 authorities: Counties and Unitaries (Home Office, 2020a). If this scale were based on women’s and children’s needs, then we would expect such authorities to be largely self-contained in terms of service access due to domestic violence. However, that is not the case, with over a third of all service access being across local authority boundaries (Bowstead, 2021a), and a much higher proportion when we consider domestic violence refuges.

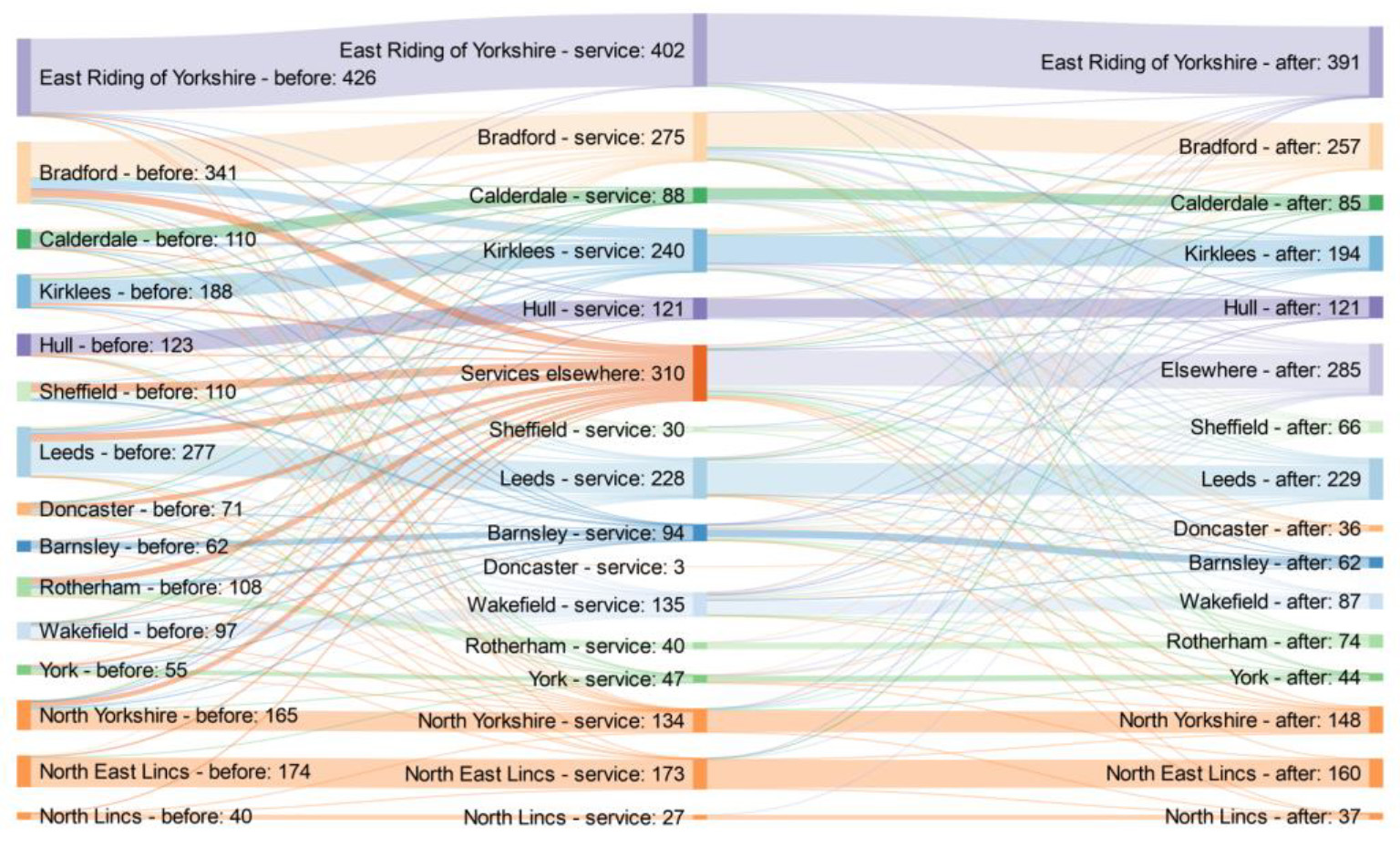

Figure 1 shows the domestic violence journeys of 2,347 women (just under half with children) from Tier 1 authorities in the region of Yorkshire and The Humber. These are all individuals who relocated at the point of accessing a service; and the services include women’s refuges, other types of temporary accommodation, as well as relocation and accessing non-accommodation support services due to domestic violence. It records the aggregate flow from the authority before accessing a service, to the location of the service, and the location on leaving the service. Whilst the numbers are often similar across all three stages, there are significant flows between local authorities, as well considerable flows to services elsewhere in the country, with two-thirds of those remaining elsewhere after leaving such services (rather than returning to the region).

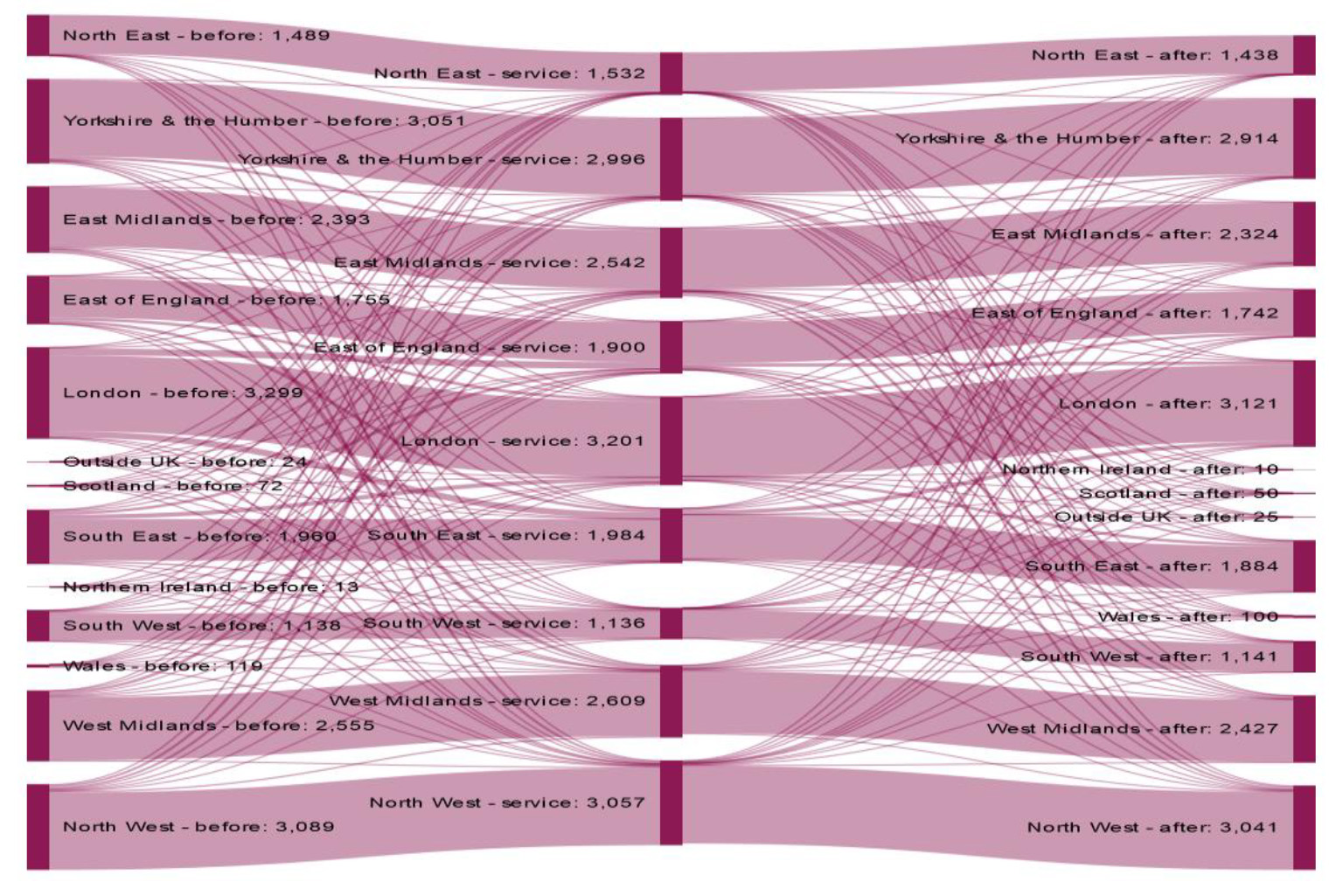

Though there are clearly domestic violence journeys out of the region, the majority stay within the same region, and Figure 2 shows that regions are much more self-contained than Tier 1 authorities. Regions vary, ranging from 93 per cent of help-seeking journeys from the North East remaining within that region, to 87 per cent from Yorkshire and The Humber, and 75 per cent from London (as the least self-contained region).

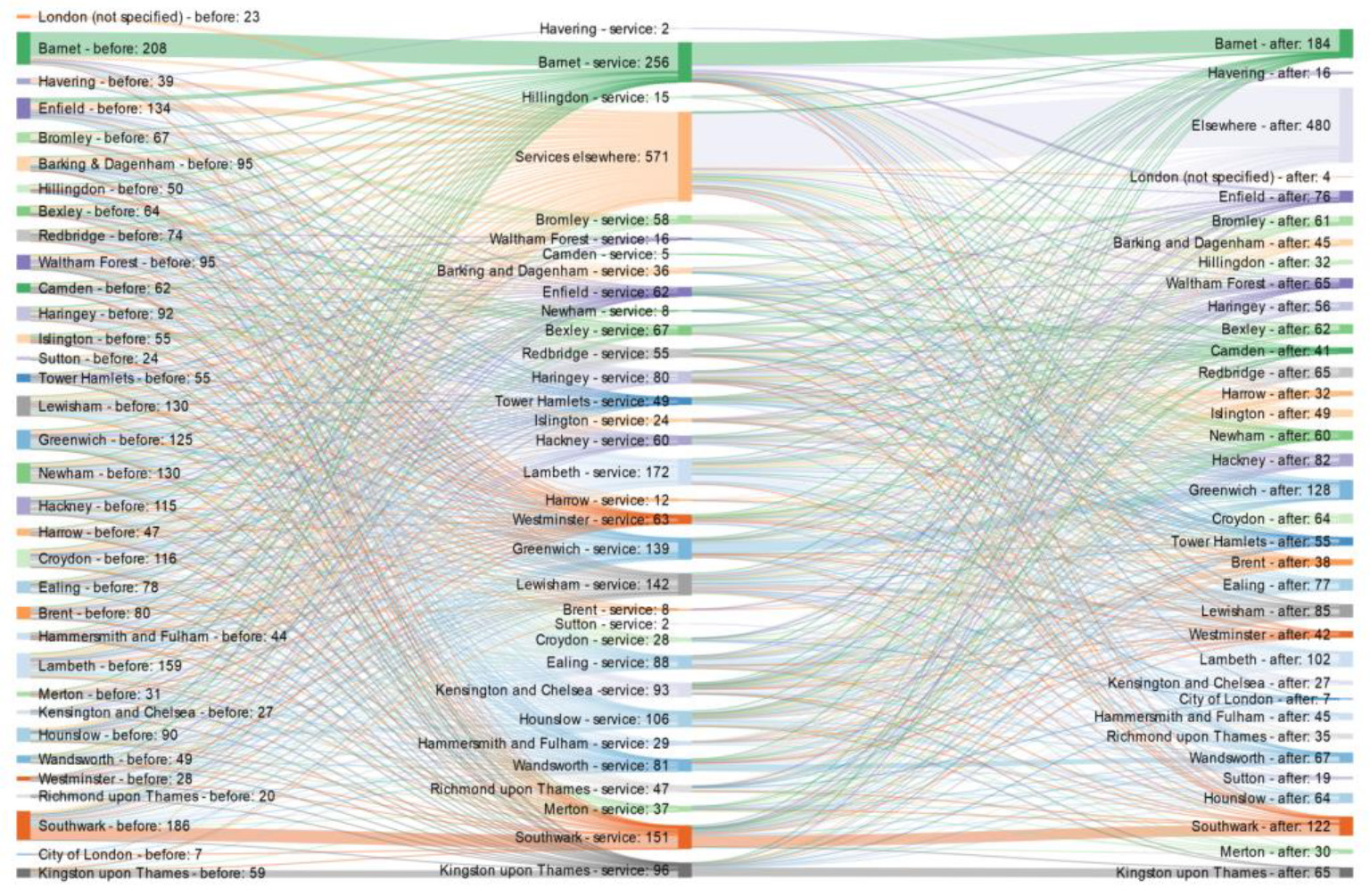

Overall, despite the uneven geography of the UK (Beatty and Fothergill, 2016) women tend to go from everywhere to everywhere that provides services – and to similar types of places when they can (Bowstead, 2015a). But that lack of overall net effect risks obscuring the mass of relocation of women and children due to abuse – the spatial churn below the surface. Not only is London the least self-contained English region, but Figure 3 shows the high level of domestic violence journeys between London Boroughs by the 2,658 women (just under half with children). Though nearly a quarter of London women go elsewhere to services, a third of these (as with Yorkshire and The Humber) return to the region after leaving the support service.

The distinctive role of women’s refuges

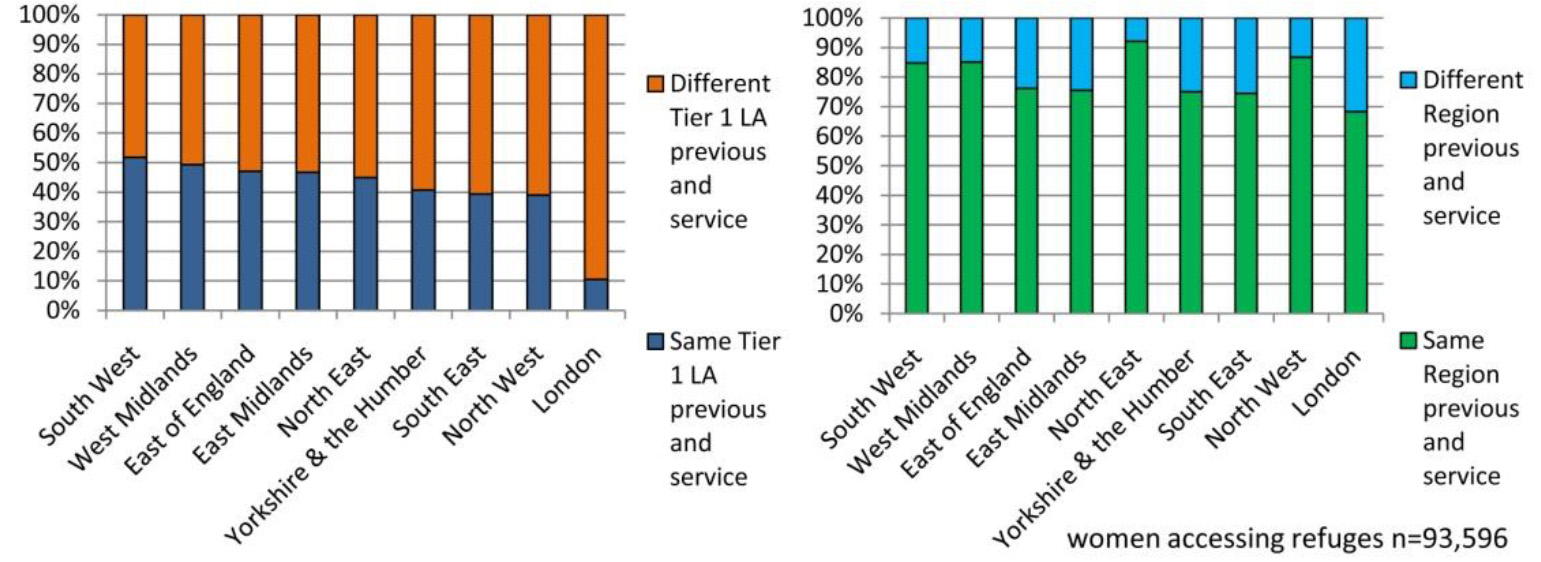

The evidence presented so far is for women’s help-seeking to a range of different accommodation services, and non-accommodation services such as floating support, outreach, and resettlement. However, it is important to note that women’s domestic violence refuges have a distinctive role for women and children escaping to an unknown place, and needing holistic and specialist support (Bowstead, 2015b, 2019b). Though all accommodation services involve a relocation journey, refuges are much more likely to be accessed across even Tier 1 local authority boundaries, with such journeys making up around 70 per cent of those accessing refuges in comparison with 36 per cent of those accessing other types of accommodation services (Bowstead, 2021a). Figure 4 shows on the left that all regions have at least half of women accessing refuges in a different County or Unitary local authority rather than remaining local, whereas, on the right, the majority remain in the same region when they go elsewhere.

Local authorities are clearly very far from being self-contained in terms of what women and children need in the context of how and where services are provided, and the mis-match between the scale of service provision – local authorities – and the scale of help-seeking – which may be regional or even further, is especially acute for the specialist provision of women’s domestic violence refuges.

Implications for policy and service provision

Patterns of women’s help-seeking are not merely of research interest but have consequences because of the implications of the scale mis-match in terms of policy and service provision. Women are often not free to seek support services in whatever location they need, or wherever they find themselves, because the local authority scale provision is often constrained by local authority scale eligibility criteria (Reis, 2019; DAHA and Women’s Aid, 2020). As a condition of local authority funding, domestic abuse services – including refuges – may be required to operate local quotas or constrained catchment areas. In addition, the administrative data presented here often represent a high point of such service capacity, with cuts and restrictions to services since 2011 (Towers and Walby, 2012; Children England, 2017). Domestic violence services can be especially vulnerable to local funding cuts both specifically (Imkaan, 2018; Women’s Aid, 2021) and as collateral damage because of being non-statutory services for local authorities during a time of austerity policies (Bennett et al., 2015). In contrast, a needs-led, rights-based approach to tens of thousands of women and children internally displaced due to domestic abuse would recognise the duty on the national state to provide an infrastructure of a range of services of sufficient capacity, across the whole country, without administrative barriers to access whenever and wherever needed.

Beyond the impact of the last decade of Government policies and action or inaction on issues that impact on women’s domestic violence journeys and rights, there has been specific legislation: Domestic Abuse Act 2021 (a ‘landmark Bill’) which claims to ‘help transform the response to domestic abuse, helping to prevent offending, protect victims and ensure they have the support they need’ (Home Office, 2021a: 1). However, it is weak and potentially counter-productive in terms of recognising and responding to the tens of thousands of women and children who cross local authority boundaries.

The Government has not provided guarantees on women’s refuges and considers them alongside other forms of accommodation services (termed ‘safe accommodation’ (Home Office, 2021b), despite the evidence presented in this article, and elsewhere, about how refuges are distinctively crucial to particular types of help-seeking. The Government has not recognised the regional and national scale of domestic abuse help-seeking and has instead, in Part 4 (UK Parliament, 2021), devolved to Tier 1 local authorities the decisions on service capacity, catchment areas, eligibility criteria and needs assessment. The Government has stated that it will not require a minimum level of service provision and that local authorities should ensure provision based on their own needs assessments. The Statutory Guidance Framework, under consultation for six weeks over the summer of 2021, states that ‘tier one local authorities must meet the needs of all victims including those who present from outside of the locality’ (Home Office, 2021c: 85) without any understanding of how someone would be able to ‘present’ in an area if the service provision is not available; or how the level of need to be able to present could or should be assessed so that such service provision is provided. It therefore creates a perverse incentive for local authorities to minimise service provision so that it is not available for women to ‘present’ themselves to as they seek help across local authority boundaries. Conversely, the fact that only around 30 per cent of women accessing refuges do so within their local authority (Quilgars and Pleace, 2010; Bowstead, 2015b) would mean that local authorities really should take the refuge capacity indicated by their local needs assessment and more than triple it to calculate the capacity actually needed within their local area (based on the calculation Local Need x (100/30)). They are unlikely to do this.

Local authorities are only required to publish their strategies and will not be required to publish their needs assessments; and the guidance (MHCLG Domestic Abuse Team, 2021: 6) on carrying out such crucial exercises is not currently publicly available, though has been seen by this author. However, the research evidence discussed in this article has shown how the local authority scale is frequently too small a scale for domestic abuse help-seeking: evidence that was provided to Government in numerous consultations (Home Office, 2020b; MHCLG, 2019a, 2019b, 2021a, 2021b). To the extent that the Government acknowledges that ‘Many survivors fleeing domestic abuse will travel across borders in order to seek help and move away from the perpetrator’ (Home Office, 2021c: 85), it nevertheless provides a tool of needs assessments by Tier 1 local authorities that could be used to ensure that survivors will not be able to access services in another local authority. Cross-border help-seeking is only mentioned in terms of survivors trying to arrive – present – in a different area, and not in terms of any duties of support for those leaving a local authority. In an already hostile landscape for women and children’s domestic violence journeys, Part 4 of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 provides perverse incentives to under-assess cross-border needs and help-seeking, which the draft guidance framework does not prevent. Unlike a Private Members Bill under the Coalition Government, which would have required service eligibility on the basis of need ‘not on the basis of the location of the place of abode of the person seeking accommodation’ and required that accommodation ‘must not be restricted to solely those from within the local authority’s boundaries’(Baker, 2014: 1), the legislation does not address the current barriers to help-seeking across local authority boundaries. Instead, national Government places the duty on local government ‘to help ensure all victims will be able to access the support they need, when they need it’ (Home Office, 2021c: 85) with a funding allocation which will not be ringfenced (MHCLG, 2021c, 2021d).

Rather than devolving to the local scale, the evidence discussed above shows that the regional scale is much more self-contained in terms of domestic abuse help-seeking. It is therefore ironic that the Government has decided that the regional scale is only relevant for London, the least self-contained region in England. Uniquely, for London, the Greater London Authority has been allocated the statutory duty to assess the need for, and to ensure the provision of, domestic abuse safe accommodation services; rather than the Tier 1 authorities of London Boroughs (Home Office, 2021b). Whilst this is to be welcomed, in terms of the duty for London being more closely aligned with women’s domestic violence help-seeking, it simply highlights that the scale of the duty is not evidence-based to be at a functional scale to meet survivors’ needs. And, fundamentally, a rights-based duty would ensure that there are no service eligibility criteria based on location at any stage. This would also require sufficient capacity of different types of services (specialist, refuge, accommodation, and non-accommodation), and across the country in all types of locations.

The statutory duty on local authorities only covers ‘safe accommodation’ and therefore only relates to women and children who relocate from their existing accommodation to seek help. As discussed above, many stay put and seek help from non-accommodation services, and a smaller proportion relocate and access support that is not associated with their accommodation. Such services have been termed community-based services; and are not covered by the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 in terms of any duty or funding. Instead, the ‘Domestic Abuse Commissioner’ (a role created by the Domestic Abuse Act 2021) is due to publish a report into the provision of such services (DAC, 2021), but – despite the name – does not have any service commissioning role or funding for provision. Meanwhile, despite the Government’s assertion that ‘it does not expect local authorities to stop funding [currently commissioned] services as a result of the introduction of the duty’ (MHCLG, 2021d: 11) it is not clear whether existing accommodation and non-accommodation services will continue to be funded by local authorities, let alone any new service capacity be developed to address the insufficient current provision in terms of specialism, location or eligibility criteria. Whilst local authorities depend on the outcome of the 2021 Spending Review (LGA, 2021) in considering how to meet the statutory duty for domestic abuse service provision, none of this will address the fact that many thousands of women and children seeking help due to domestic abuse journey at a regional or national, not just a local, scale.

Conclusion

The scale of domestic abuse service provision – both scale as capacity and geographical scale – in England has historically not been systematically evidence-based nor based on principles and rights which recognise violence against women as a human rights violation. Similarly, the legislative and administrative governance allocating duties to national or local government are not aligned with the evidence of how and where women and children seek help from different types of services. The recent legislation of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, with Part 4 creating new duties on local government, does not remedy this mis-match of scale; in fact, it potentially cements or exacerbates the inequalities and injustices.

This article has presented evidence in the administrative record of women and children’s help-seeking to formal services in the period up to 2011, showing the significant spatial churn of domestic violence journeys between local authorities, as well as the general lack of net effect as flows tend to cancel each other out. It records women’s strategies in terms of place, and their use of different types of service, but it only records those who successfully accessed a service. It presents an increasingly historical picture, though one that reflects a higher level of service provision in some areas than is currently the case. There is no evidence that the relocation forced by abusers has significantly reduced, and there is evidence of increased relocation across local authority boundaries forced by barriers for women accessing homelessness support and statutory authorities using “Out of area placements” under temporary accommodation provision (Rosa et al., 2019: 8; Schofield, 2021). Relocation may therefore be a strategy forced on women and children by how the state provides services, rather than what women and children actually need in terms of safety from the abuser. Despite the lack of net effect at the local authority scale, at the individual scale the displacement and disruption remain considerable; with practical and emotional losses on the way. Women and children often make complex multi-stage journeys, initially forced by the abuser, but subsequently forced or blocked by the availability or not of the services and support they need. Rather than a coherent and rational infrastructure of support, of sufficient capacity throughout the country, women and children encounter a fragmented and hostile landscape without the means and the information to be able to navigate it.

In devolving the duty to provide accommodation for those on the move due to domestic abuse to local government, national Government is risking creating perverse incentives for local authorities to underestimate cross-border needs and therefore claim the justification to reduce or limit provision. Rather than journeyscaping women’s domestic violence help-seeking, by metaphorically building bridges and mapping routes – even just putting up signposts – local authorities may further pull up their drawbridges against incoming women and children, and refer their own women across the boundary so that they have no further duty to assist. As a result, rather than contributing to building a more effective and supportive network of services, the Government risks hostility between neighbouring local authorities with incompatible assessments and understandings of needs and consequent provision. Women and children are likely to continue to experience barriers and exclusions – causing complex journey trajectories – and increased displacement due to the actions of the state (beyond the initial cause of the abuser).

Whilst this article has shown the regional scale in England to be more self-contained than local authorities in terms of accessing services, this is not currently a scale of service commissioning. And, in the one region – London – that the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 recognises as a functional scale for service planning and commissioning, a quarter of women go elsewhere to seek formal help (more, incidentally, than travel into London to access services). A rights-based, needs-led framing of service provision would plan at the national scale, including recognising journeys to and from the other UK nations, and fundamentally ensure sufficient and sustainable service capacity, without any access restrictions in terms of past, present, or future location. A human rights argument would be for all options to be possible without any additional harm or losses being caused by the state in terms of policies, laws, and services. As Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the UK, the state should have duties to minimise individuals’ losses, and support their rights and resettlement. Women and children should be enabled to journey as far as they need, and stay as near as they can, with the role of the state authorities being to journeyscape (by law, policy, and provision) an otherwise potentially hostile terrain.

This research (Bowstead, 2021b) has developed a formula for minimum provision of key specialist support services – women’s refuges, other specialist accommodation and non-accommodation services (such as support, resettlement and outreach that go to where women and children are and are not restricted or allocated on the basis of risk assessments). The capacity is based on expressed demand – help-seeking – from the administrative records and average length of time in services. Whilst it is possible to calculate the expressed demand from each local authority and a potential typology of places (Lupton et al., 2011), the fundamental mis-match of scale remains. It is possible to provide a measure of service need from a particular local authority, but this research has shown that such need often requires provision actually to be located elsewhere. The administrative data analysed here record what happened in terms of service access, and cannot indicate what women and their children would have wanted to happen following their experience of abuse. Any relocation is likely to be disruptive in practical and emotional ways, and to affect rights, independence, and freedom. However, in the current context of inadequate and unjust policy and practice responses – not least the systematic failure to hold perpetrators of domestic abuse to meaningful account (Ofsted et al., 2017; Coy and Kelly, 2019) – relocation remains a key strategy for women. In this context of limited options, and a fragmented service landscape of insufficient capacity, over 60 per cent of refuge access, over 30 per cent of other accommodation access, and even five per cent of non-accommodation access was across local authority boundaries. Planning, commissioning, and funding services at the local authority scale will clearly never bridge the mis-match of scale: will never create the service infrastructure women and children not only need, but should have as of right.

Thanks to all the women who are sharing their experiences and insights for this research.

Administrative data from the UK Data Archive, Colchester, Essex.

This work was supported by a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship (grant number PF160072).

Janet C. Bowstead, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX. Email: Janet.Bowstead@cantab.net

Baker, N. (2014) Women’s Refuges (Provision and Eligibility) Bill. Available at: https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/1533 [Accessed: 12/08/21]

Beatty, C. and Fothergill, S. (2016) The Uneven Impact of Welfare Reform: The financial losses to places and people. Sheffield: Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University. CrossRef Link

Bennett, E., Langmead, K. and Archer, T. (2015) Editorial: Special issue – Austere relations: The changing relationship between the Third Sector, the State and the Market in an era of austerity. People, Place and Policy, 9, 2, 100–102. CrossRef link

Bowstead, J. C. (2015a) Forced migration in the United Kingdom: women’s journeys to escape domestic violence. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 40, 3, 307–320. CrossRef link

Bowstead, J. C. (2015b) Why women’s domestic violence refuges are not local services. Critical Social Policy, 35, 3, 327–349. CrossRef link

Bowstead, J. C. (2017a) Women on the move: theorising the geographies of domestic violence journeys in England. Gender, Place and Culture, 24, 1, 108–121. CrossRef link

Bowstead, J. C. (2017b) Segmented journeys, fragmented lives: Women’s forced migration to escape domestic violence. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 1, 1, 43–58. CrossRef link

Bowstead, J. C. (2018a) What about the men? London. Available at: https://www.womensjourneyscapes.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Womens-Journeyscapes-Briefing-paper-2-June-2018.pdf [Accessed 21/10/2022]

Bowstead, J. C. (2018b) Changing journeys into journeyscapes: enhancing women’s control over their domestic violence mobility. Mobile and Temporary Domesticities 1600-2017. Available at: https://mobiledomesticities2017.wordpress.com/2018/01/29/changing-journeys-into-journeyscapes-enhancing-womens-control-over-their-domestic-violence-mobility/ [Accessed 21/10/2022]

Bowstead, J. C. (2019a) Women on the move: administrative data as a safe way to research hidden domestic violence journeys. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 3, 2, 233–248. CrossRef link

Bowstead, J. C. (2019b) Spaces of safety and more-than-safety in women’s refuges in England. Gender, Place and Culture, 26, 1, 75–90. CrossRef link

Bowstead, J. C. (2021a) Stay Put; Remain Local; Go Elsewhere: Three Strategies of Women’s Domestic Violence Help Seeking. Dignity: A Journal of Analysis of Exploitation and Violence, 6, 3, 4. CrossRef link

Bowstead, J. C. (2021b) Women’s Journeyscapes: Women and children relocating due to domestic abuse. Available at: https://www.womensjourneyscapes.net/ [Accessed 21/10/2022]

Centre for Housing Research (2015) Closure of CHR Client Records and Outcomes Project. Available at: http://ggsrv-cold.st-andrews.ac.uk/CHR/news/SP%202015.aspx [Accessed: 06/01/2018]

Children England (2017) Beneath the Threshold: Voluntary sector perspectives on child safeguarding in London. London: Children England. Available at: https://www.childrenengland.org.uk/beneath-the-threshold [Accessed: 31/07/2021]

Clarke, N. (2013) Locality and localism: a view from British Human Geography. Policy Studies, 34, 5–6, 492–507. CrossRef link

Cox, E. (2014) Decentralisation and Localism in England. In: G. Lodge and G. Gottfried (Eds.), Democracy in Britain: Essays in honour of James Cornford. London: Institute for Public Policy Research, pp. 145–159.

Coy, M. and Kelly, L. (2019) The responsibilisation of women who experience domestic violence: a case study from England and Wales. In: C. Hagemann-White, L. Kelly, and T. Meysen (Eds.) Interventions Against Child Abuse and Violence Against Women: Ethics and culture in practice and policy Cultural Encounters in Intervention Against Violence, Vol.1. Opladen, Berlin, Toronto: Barbara Budrich Publishers, pp. 151–163. CrossRef link

Coy, M., Kelly, L. and Foord, J. (2009) Map of Gaps 2: The postcode lottery of Violence Against Women support services in Britain. London: End Violence Against Women and Equality and Human Rights Commission. Available at: https://www.endviolenceagainstwomen.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/map_of_gaps2.pdf [Accessed: 14/04/2018]

Coy, M., Kelly, L., Foord, J. and Bowstead, J. C. (2011) Roads to Nowhere? Mapping Violence Against Women Services. Violence Against Women, 17, 3, 404–425. CrossRef link

DAC (2021) National Mapping of Domestic Abuse Services: Survey open Tuesday 6th July – 3rd August. London: Domestic Abuse Commissioner. Available at: https://domesticabusecommissioner.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/National-Mapping-Guidance-and-QA.pdf [Accessed: 30/08/2021]

DAHA and Women’s Aid (2020) Improving the move-on pathway for survivors in refuge services: A recommendations report. London and Bristol: Domestic Abuse Housing Alliance and Women’s Aid. Available at: https://www.dahalliance.org.uk/media/10928/improving-the-move-on-pathway-for-survivors-in-refuge-services-wa-daha.pdf [Accessed: 07/01/2021]

DCLG (2011) A plain English guide to the Localism Act. Department for Communities and Local Government. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/localism-act-2011-overview [Accessed: 16/09/2021]

DCLG (Department for Communities and Local Government) and University of St Andrews, Centre for Housing Research (2012) Supporting People Client Records and Outcomes, 2003/04-2010/11: Special Licence Access [computer file] (No. SN: 7020). Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor]. 10.5255/UKDA-SN-7020-1.

Gore, T. (2018) Cities and their hinterlands 10 years on: Local and regional governance still under debate. People, Place and Policy, 11, 3, 150–164. CrossRef link

Home Office (2016) Violence Against Women and Girls Services: Supporting Local Commissioning. London: Home Office. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data

/file/576238/VAWG_Commissioning_Toolkit.pdf [Accessed: 07/01/2021]

Home Office (2020a) Local authority support for victims of domestic abuse and their children within safe accommodation factsheet (2020 version). London: Home Office. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/domestic-abuse-bill-2020-factsheets/local-authority-support-for-victims-of-domestic-abuse-and-their-children-within-safe-accommodation-factsheet [Accessed: 31/01/2021]

Home Office (2020b) Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) strategy 2021-2024: call for evidence. London: Home Office. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/violence-against-women-and-girls-vawg-call-for-evidence [Accessed: 31/01/2021]

Home Office (2021a) Domestic Abuse Act 2021: overarching factsheet. London: Home Office. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/domestic-abuse-bill-2020-factsheets/domestic-abuse-bill-2020-overarching-factsheet [Accessed: 06/06/2021]

Home Office (2021b) Local authority support for victims of domestic abuse and their children within safe accommodation factsheet. London: Home Office. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/domestic-abuse-bill-2020-factsheets/local-authority-support-for-victims-of-domestic-abuse-and-their-children-within-safe-accommodation-factsheet [Accessed: 06/06/2021]

Home Office (2021c) Domestic Abuse: Draft Statutory Guidance Framework. London: Home Office. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/

1007814/draft-da-statutory-guidance-2021-final.pdf [Accessed: 30/08/2021]

Imkaan (2018) From Survival to Sustainability: critical issues for the specialist black and ‘minority ethnic’ ending violence against women and girls sector in the UK. London: Imkaan. Available at: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/2f475d_9cab044d7d25404d85da289b70978237.pdf / https://www.imkaan.org.uk/resources [Accessed: 30/06/2020]

Imkaan and Women’s Aid (2014) Successful Commissioning: a guide for commissioning services that support women and children survivors of violence. Bristol: Imkaan and Women’s Aid. Available at: https://www.womensaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/successful_commissioning_guide.pdf [Accessed: 31/01/2022]

Jacobs, K. and Manzi, T. (2013) New Localism, Old Retrenchment: The “Big Society”, Housing Policy and the Politics of Welfare Reform. Housing, Theory and Society, 30, 1, 29–45. CrossRef link

LGA (2020) Fragmented funding – the complex local authority funding landscape. London: Local Government Association. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/fragmented-funding-complex-local-authority-funding-landscape [Accessed: 20/10/2020]

LGA (2021) Domestic Abuse Act 2021 (Get in on the Act). London: Local Government Association. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/publications/domestic-abuse-act-2021-get-act [Accessed: 31/07/2021]

Lupton, R., Tunstall, R., Fenton, A. and Harris, R. (2011) Using and developing place typologies for policy purposes. London: Department for Communities and Local Government. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120919150511/http://www.communities.gov.uk/

documents/corporate/pdf/1832148.pdf [Accessed: 02/01/2021]

MHCLG (2019a) Domestic Abuse Services: Future Delivery of Support to Victims and their Children in Accommodation-Based Domestic Abuse Services. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/support-for-victims-of-domestic-abuse-in-safe-accommodation [Accessed: 16/09/2021]

MHCLG (2019b) Future delivery of support to victims and their children in accommodation-based domestic abuse services: consultation response. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/839171/

Domestic_Abuse_Duty_Gov_Response_to_Consultation.pdf [Accessed: 16/09/2021]

MHCLG (2021a) New duties on local authorities to provide domestic abuse support in safe accommodation in England: consultation. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/domestic-abuse-support-within-safe-accommodation-statutory-guidance-and-regulations-consultation [Accessed: 07/07/2021]

MHCLG (2021b) Delivery of Support to Victims of Domestic Abuse, including Children, in Domestic Abuse Safe Accommodation Services: Statutory guidance for local authorities across England. Issued under the Draft Domestic Abuse Bill 20XX. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_

data/file/955574/Statutory_Guidance_Part_4_DA_Bill_-_DRAFT__003_.odt [Accessed: 11/05/2021]

MHCLG (2021c) Funding allocation methods: new domestic abuse duty. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/funding-allocation-methods-new-domestic-abuse-duty [Accessed: 24/04/2021]

MHCLG (2021d) Domestic abuse safe accommodation funding allocation: consultation response. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/funding-allocation-methods-new-domestic-abuse-duty/outcome/domestic-abuse-safe-accommodation-funding-allocation-consultation-response [Accessed: 24/04/2021]

MHCLG Domestic Abuse Team (2021) MHCLG SPRING WORKSHOP Q & A: part 4 Domestic Abuse Bill. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. Available at: www.gov.uk/mhclg

ODPM (2002) Supporting People: Guide to Accommodation and Support Options for Households Experiencing Domestic Violence. ODPM. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20091211213042/http://www.spkweb.org.uk/NR/rdonlyres/

C5A1BAEC-2F69-4BB3-8338-3F6F623DB852/1771/Guide_to_Accomodation_and_Support_Options_for_Hous.pdf [Accessed: 16/09/2021]

Ofsted, IOP, HMICFRS and CQC (2017) The multi-agency response to children living with domestic abuse: Prevent, protect and repair (No. 170036). London: Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted), Inspectorate of Probation (IOP), Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS), Care Quality Commission (CQC). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/joint-inspections-of-the-response-to-children-living-with-domestic-abuse [Accessed: 30/05/2020]

ONS (2020) Domestic abuse in England and Wales overview: November 2020. London: Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/domestic

abuseinenglandandwalesoverview/latest [Accessed: 31/07/2021]

Parvin, P. (2009) Against Localism: Does Centralising Power to Communities Fail Minorities? Political Quarterly, 80, 3, 351–360. CrossRef link

Quilgars, D. and Pleace, N. (2010) Meeting the needs of households at risk of domestic violence in England: The role of accommodation and housing-related support services. London: Department for Communities and Local Government. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/helping-households-at-risk-of-domestic-violence-housing-related-support-services [Accessed: 18/11/2013]

Reis, S. (2019) A home of her own: Housing and Women. London: Women’s Budget Group. Available at: https://wbg.org.uk/analysis/reports/a-home-of-her-own-housing-and-women/ [Accessed: 16/09/2021]

Rosa, G., King, L., Stephens, M. and Smith, L. (2019) State of Children’s Rights 2018: Poverty & Homelessness. London: Children’s Rights Alliance for England. Available at: http://www.crae.org.uk/publications-resources/state-of-childrens-rights-2018/ [Accessed: 09/02/2022]

Schofield, M. (2021) Fobbed Off: The barriers preventing women accessing housing and homelessness support, and the women-centred approach needed to overcome them. London: Shelter. Available at: https://england.shelter.org.uk/professional_resources/policy_and_research/policy_library/fobbed

_off_the_barriers_preventing_women_accessing_housing_and_homelessness_support / https://assets.ctfassets.net/6sxvmndnpn0s/3fo63KyM9D5qJedQvxe7A6/df905542ec226fd909388759727059d0/

Fobed_off_women-centred_peer_research_report_FINAL.pdf [Accessed: 19/01/2022]

Swyngedouw, E. (2005) Governance Innovation and the Citizen: The Janus Face of Governance-beyond-the-State. Urban Studies, 42, 11, 1991–2006. CrossRef link

Towers, J. and Walby, S. (2012) Measuring the impact of cuts in public expenditure on the provision of services to prevent violence against women and girls. Trust for London & Northern Rock Foundation. Available at: https://www.trustforlondon.org.uk/publications/measuring-impact-cuts-public-expenditure-provision-services-prevent-violence-against-women-and-girls/ [Accessed: 16/09/2021]

UK Parliament (2021) Domestic Abuse Act 2021. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/17/contents/enacted [Accessed: 16/09/2021]

UN CEDAW Committee (2017) General recommendation No. 35 on gender-based violence against women, updating general recommendation No. 19 (No. CEDAW/C/GC/35). Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations. Available at: http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CEDAW/C/GC/35&Lang=en [Accessed: 16/09/2021]

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (1999) Handbook for applying the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. Geneva, Switzerland: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/protection/idps/50f94df59/handbook-applying-guiding-principles-internal-displacement-ocha-november.html [Accessed: 16/09/2021]

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2004) Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement: 2nd edition. Geneva, Switzerland: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/protection/idps/43ce1cff2/guiding-principles-internal-displacement.html [Accessed: 02/12/2020]

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2017) States must provide shelters as “survival tool” for women victims of violence – UN expert. Geneva, Switzerland: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21724&LangID=E [Accessed: 16/09/2021]

Women’s Aid (2021) Fragile funding landscape: The extent of local authority commissioning in the domestic abuse refuge sector in England 2020. Bristol: Women’s Aid. Available at: https://www.womensaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Fragile-funding-landscape-the-extent-of-local-authority-commissioning-in-the-domestic-abuse-refuge-sector-in-England-2020.pdf [Accessed: 08/03/2021]