Abstract

Community food projects (CFPs) have diverse purposes relating to correcting market failures, community cohesion and not-for-profit operation. These are well served by social innovations relative to technical and/or economic ones. Whilst innovation is invariably associated with ‘new’ ideas, innovation theory accommodates learning from the past, acknowledging its relative neglect. This paper explores the extent to which the purposes and innovative actions of CFPs are informed by past practice. The significance of a ‘re-turn’ in food is assessed, where policies for regenerative agriculture, relocalisation and food resilience all draw on ‘the way we used to do things’. The flexibility of social innovation, too, has meant recourse to past practice in emergency responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Empirical evidence from three research projects which benchmark historical food practice against contemporary actions of CFPs, identifies both explicit reference to historical practice to inform current behaviour, as well as the mimicking of past practice. Close examination of historical food innovations to inform current practice allows choices to be made in adopting or adapting such innovations or identifying what to avoid.

Introduction and summary

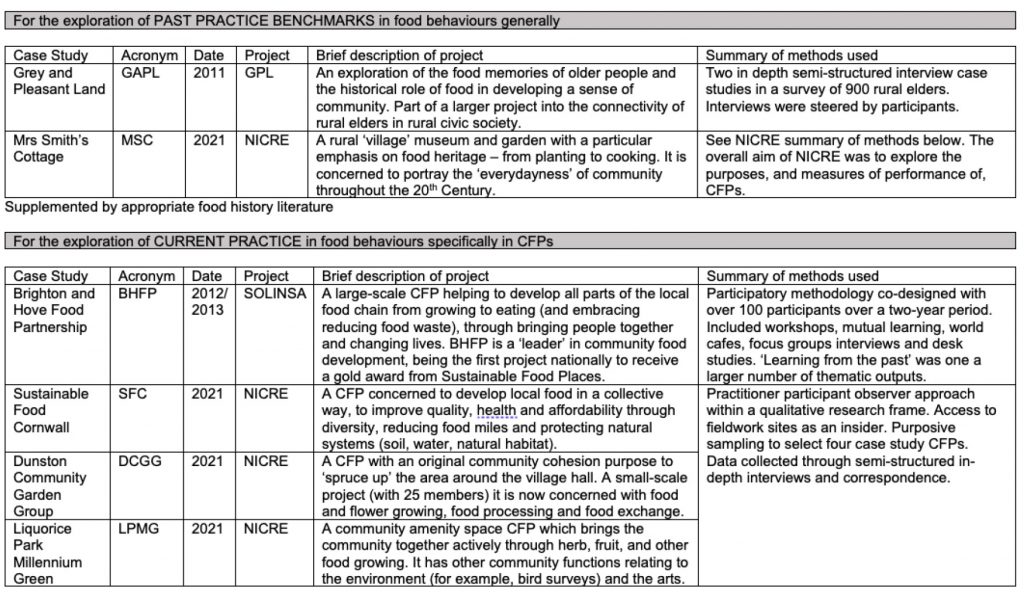

Community food projects (CFPs) have had a contemporary resurgence from the early 1960s, according to Feagan (2007), born of an increasing discomfort with the impacts of a globalising, intensive high-input high-output agriculture. They elude simple definition (or even consistent terminology) but they all have in common food (embracing all aspects from seeds and production, through distribution and preparation to consumption and waste), community involvement (management, delivery, volunteering) (Pearson and Firth, 2012) and, suggest Dowler and Caraher (2003), some form of third party support (sponsorship, grants, state support). Several examples of specific CFPs are described in Table 1. Over this period, CFPs have changed considerably, most commonly through processes of social innovation (Matson et al., 2013).

To examine the nature of this innovative change more closely, the research focus of this paper is to explore one aspect of such change: the extent to which the purposes and innovative actions of CFPs are informed by past practice. The role of the past in influencing CFP behaviour has hitherto received scant attention in the literature. This exploration is undertaken through a novel application of theories of innovation and nostalgia to this change process.

The stated research focus is addressed, firstly, by defining terms. The nature of CFPs is reviewed from the literature to establish their dominant purposes. These purposes form the analytical framework for further empirical exploration. Theories of innovation are then evaluated for two specific reasons: firstly, to establish a connection between change in CFPs and social innovation practices and, secondly, to explore the role that the past legitimately can have to play in innovative action. The review section of the paper concludes with a brief assessment of the way in which ‘the past’ and past practice is increasingly acknowledged in contemporary food innovation through a ‘re-turn’, exemplified by food responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The use of past practice to inform contemporary social innovation in CFPs was an unanticipated finding in earlier research (Curry and Kirwan, 2014). In exploring this issue further empirically, a series of benchmarks of ‘the way we used to do things’ in food was set up for comparison with contemporary practice. These were drawn from two surveys, firstly of older people’s food memories and secondly of a rural museum specialising in food histories. These were supplemented with appropriate documented food past practice. Contemporary practice was then compared with these historical benchmarks, by reanalysing the findings of the earlier 2014 study, and through in-depth semi-structured interviews in 2021 with three further CFPs. The analytical frame adopts the structure of the literature review of CFPs.

Conclusions indicate that indeed much contemporary CFP practice explicitly acknowledges past practice, and other practices mimic it. A close study of historical food practices can enrich contemporary innovations by using or adapting the best but also, by avoiding the worst, through a process of critical learning.

Community food projects

CFPs within local food systems are growing considerably on a worldwide scale (Stevenson and Pirog, 2008). In the UK, they embrace all manner of initiatives including food hubs (Psarikidou et al., 2019), food banks and community cafes (Lambie-Mumford, 2019), food museums (Allen, 2012), community growing projects and gardens (Guerlain and Campbell, 2016), and community food waste projects (Facchini et al., 2018).Within these categories, each project is unique, but one way of framing them is to consider their dominant purposes.

CFPs have grown for a variety of reasons. Their counterposition to monopolistic, and distant agri-industrial food systems has led them, wittingly or not, to have purposes concerned with tackling several market failures that the global food market leaves behind (Weber et al., 2020). In this regard, environmental externalities are felt to be the most longstanding challenge of CFPs in the UK (Yarnit, 2021). These commonly are addressed through tackling food waste (Papargyropoulou et al., 2014), promoting shorter food miles (Stroink and Nelson, 2013) and promoting lower input-output agriculture (Berti and Mulligan, 2016). A second market failure is food insecurity and more global food issues such as fossil fuel dependence, crop failures, intensive animal production, soil erosion, climate change and resource depletion (including water) (Seekell et al., 2017). This includes addressing the increasing complexity of food systems, both local and global (Weber et al., 2020).

A third concerns food disadvantage. Here, purposes embrace ameliorating food poverty, improving access to food, and pursuing food justice (Rose, 2017). Food education (nutrition, diet), and practical cooking classes are part of this support (Blay-Palmer et al., 2013). Associated with this is a fourth market failure – addressing food-related poor health (obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease (Public Health England, 2016)), through reducing the consumption of ultra-processed foods (Lang, 2020), improving diets and nourishment, promoting healthier eating (Dwivedi et al., 2017) and reconnecting people with food (Lindgren et al., 2018).

In addition to tackling food market failures, developing community cohesion also is a critical CFP purpose (Le Blanc et al., 2014). Self-organised connectivity has been found to be important in developing CFPs (Hinrichs, 2000), which develops out of collaboration (Beckie et al, 2012). Such developments have been seen to nurture both community-building (Renting et al., 2003) and an increase in commitment through volunteering (McKeon, 2015) in CFPs. A core characteristic of community cohesion in CFPs is the relocalisation of food (Chiffoleau and Dourian, 2020).

Pursuing these purposes means that CFPs inevitably do not adopt conventional business models for their survival. ‘Not for profit’ strategies commonly are deliberately adopted, using a blend of community shareholding, grant-aid support, donations, volunteering, and some income generation (Yarnit, 2021), with a social enterprise structure that commonly reinvests any surpluses for community ends rather than to maximise profit (Crabtree et al., 2012). Because of these characteristics CFPs commonly adopt social economy forms such as community interest company, cooperative, mutual benefit society or charity (Curry and Purle, 2021). All of these purposes: a concern to address market failures (environment, food disadvantage, food related poor health, food insecurity); community cohesion, and not-for-profit operation, inform the structure of the empirical analysis presented below.

Theories of innovation

How do CFPs develop these purposes into practice? Stroink and Nelson (2013) assert that, because of their impetus for change, their relative ‘newness’, and their diverse constituencies, CFPs tend to be particularly innovative, as they see local food systems in counterposition to global ones. They note that such CFPs commonly experiment with novel ideas (not always successfully) often because of a lack of experience of ‘conventional’ food growing practices. They contrast this with the global industrial food system which, they claim, suffers from a rigidity trap (page 632) where there is a resistance to innovation because of doing things in established ways using relatively homogenous technologies. This can make the global food system both defensive of its modus operandi, and more vulnerable to major disturbances.

This counterposition of local community-based CFPs and industrial high technology global agriculture, suggest Klerkx and Leeuwis (2009), also counterposes innovation types. CFPs exhibit high degrees of social innovation whereas industrial agriculture – where innovation does take place – places an emphasis on technical and economic innovation (Seyfang and Haxeltine, 2012). Whilst social innovation has been narrowly defined as “new ideas that meet social needs, create social relationships and form new collaborations” (European Commission, 2014), it is felt to have a very wide societal scope (Nicholls et al., 2015). Specific CFP social innovations are discussed in the literature, such as transitioning from productivist institutions to considering consumer food needs (Fardkhales and Lincoln, 2021), school food quality (Yarnit, 2021) and tackling food deserts (Matson et al., 2013). At the smaller scale, too, social innovations are held to include solidarity purchase groups, non-monetary food exchanges (McLain et al., 2014) and actions such as gleaning and foraging (Grasseni, 2014).

In exploring theories of innovation more generally, the dominant view is that innovation of all types concerns creating the ‘new’ (Rogers, 2004): it is rarely seen to lean heavily on past practice. But there are dissenting views from this dominant position. Shove and Walker (2010) assert that innovation concerns transition, and transition is both temporal and non-linear (Røpke, 2009). Adams and Hess (2008), too, note that innovation can be the use of ‘old’ ideas in new contexts “to stimulate different ways of thinking and acting” (p. 1).

Hargreaves et al. (2013) draw a distinction between two specific theoretical approaches to innovation in its temporal context. The first has a focus on new innovations as they unfold (Geels and Schot, 2007), on niches and novelty (commonly through vertical linkages) and the development of new standards and visions for the future (Smith, 2012). They consider this approach to be consistent with multilevel perspective theory (MLP), explored more fully in Rip and Kemp (1998). A second theoretical perspective casts innovation more generally in the now (and the path dependency of ‘now’ (Reckwitz, 2002)) rather than the new. In this framework, innovation emerges from normality and the existing systems already in place (commonly through horizontal linkages). Here, innovation is actually done in an integrated way. Hargreaves et al. (2013) consider this approach to fall into social practice theory (SPT), developed fully in Bourdieu (1977). Much of their discussion focuses on the relationship and complementarity between these vertical and horizontal approaches.

Postmodern and poststructuralist interpretations of innovation have a little more to say about innovation and the past (Lupton, 1996). Callon (2007), for example, suggests that linear models of innovation (both horizontal or vertical) are limited because, actually, innovation is much more iterative and haphazard than linear: whilst haphazardness inevitably embraces the past, iteration ‘plays’ with the past. Furthermore, Nyström (2013) sees innovation as the “logical result of pre-existing conditions rather than a creative surprise leading to new experiences” (p. 19).

But none of the ‘new’ (MLP), the ‘now’ (SPT) or the ‘haphazard’ (postmodernism) has a clear focus on the role that history or heritage has on spawning social innovation: the area described by Pantzar and Shove (2010) as ‘ex-practice’ and by Shove (2010) as ‘forgotten’ practices. Such a focus is commonly dismissed as mere nostalgia – itself, long the object of systematic criticism for its association with reactionary ideologies and misrepresentations of history (Burstrom, 2021). González-Ruibal (2021) asserts that nostalgia is commonly viewed as the opposite of progress, and therefore, sentimental and melancholic: a yearning for the unattainable. This is hardly a basis for social innovation.

But Pickering and Keightley (2006) contest these views suggesting that they are again based on the assumption of a linear model of social innovation – there is ‘no going back’. They suggest, to the contrary, that returning to examine ‘the way we used to do things’ is an essential part of innovation and a strong “basis for renewal and satisfaction in the future” (page 921). Nostalgia can be seen as “a viable alternative to the acceleration of historical time” (page 923) – a counter to developmental vertigo. To dismiss nostalgia is to deny historical experience, both good and bad. As Pickering and Keightley (2006) conclude, citing Rosaldo (1993):

“We valorise innovation, and then yearn for more stable worlds” (page 933).

In providing an original contribution to this debate, the role that the past has to play in contemporary innovative community food practice merits further exploration. This is undertaken in this paper by exploring Shove’s (2010) ‘forgotten’ practices and Pickering and Keightley’s (2006) ‘the way we used to do things’ through an examination of social innovation in CFPs. To set the context for an empirical investigation of these practices, the role of the past in general contemporary food practice briefly is reviewed.

The ‘past’ in contemporary food innovation

The 2021 National Food Strategy for England (Part 2), the first national strategy in the UK for food in more than 70 years, accords social innovation from the past comparable status to ‘new’ technical innovation. In the introduction to its recommendations for a long-term shift in food culture, it begins:

“We cannot make lasting changes to the food system without innovation in the widest sense. We need to change the way we use our land, reintroducing forgotten farming wisdom while simultaneously developing robots and AI to serve the farms of the future” Dimbleby (2021), Page 159 (author’s emphasis).

The consultation in the development of the National Food Strategy made extensive recourse to words beginning with the ‘re- prefix – a language in the ascendency in the UK food lexicon. This ‘re-turn’ places past practice at the centre of a range of new developments in food. Re-generative agriculture (Giller et al., 2021) features in the new UK agricultural policy of Environmental Land Management Schemes. Soil re-storation will improve biodiversity and soil re-silience (Tendall et al., 2015) and reduce inputs (Newton et al., 2020). On re-generative agriculture, Professor Jane Rickson of Cranfield University comments:

“Farmers are getting engaged with new practices and some not so new practices – some of them are very traditional practices – that help not only to conserve soil but also to re-generate soil” (BBC Radio 4, Farming Today, 24 June 2021) (author’s emphasis).

These “not so new” practices describe well Pickering and Keightley’s (2006) ‘the way we used to do things’ in social innovation.

As well as this re-surgence in the food production context there is much recent discussion of agricultural and food re-localisation (Jones et al., 2019) – ‘going back’ to the local in food. This, too, makes recourse to learning from the past and recreating historic modes of production, distribution and consumption at a scale that largely has been lost in commercial food production (Lawson, 2005). It offers for CFPs a useful community counterposition to globalisation, or a vehicle for the Western ‘sustainability’ turn, or both (Feagan, 2007).

Re-localisaton can help, too, in pursuing environmental and food security purposes (for example, shortened food chains (Grasseni, 2014)), as it strengthens local economies, making them more re-silient and socially and environmentally more equitable (Post Carbon Institute, 2021). Re-localising also has been seen to rebalance food system power (Winter, 2003) and enhance food sovereignty (Watts et al., 2005) – part of the CFP purpose of tackling food disadvantage – as well as to reinforce local identity, using food to build community, food quality, and traceability (Jones et al, 2019).

As well as this ‘re-turn’ in the contemporary food lexicon, there is some evidence to suggest that food emergency responses in the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 – particularly by CFPs – also have drawn on social innovations from past ‘emergency’ food practice. Adger (2000) suggests that this is inevitable because social innovations can be very quick to implement responsively, in contrast to technical and economic innovations which invariably have long lead-in times and are more deliberative. Thus, in terms of the market failure purposes of CFPs the use of back gardens, vacant land, foraging and gleaning to develop innovative food supply through voluntary effort by CFPs in the COVID-19 pandemic (Henry, 2020) parallels the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaigns, the conversion of public lands for food growing, the creation of new allotments (Chavalier, 2016a) and the consumption of ‘wild’ foods (Vorstenbosch et al., 2017) of the Second World War (WWII). Food poverty market failures have been comparably addressed as CFPs have diverted a proportion of their ‘local’ output to food banks in the pandemic (Power et al., 2020) similar to contributions to ‘soup kitchens’ of the war (Collingham, 2011). In both crisis periods, too, diets adjusted towards the increased consumption of local, fresh, plant-based produce (Way, 2015) which, in both periods, too, was, and is, felt to address food-related poor health market failures (Walljasper and Polansek, 2020).

Community cohesion purposes of CFPs have been at the forefront in the pandemic, too, through imperatives for solidarity and mutual support stimulated, suggests Lal (2020), by re-collections of the way things used to be done. The ‘not-for-profit’ purposes, particularly in respect of innovations in informal food distribution, also have historic parallels. As local ‘back garden’ food production commonly orchestrated by CFPs gained momentum in the pandemic, it was increasingly shared and processed outside of monetary exchange (Henry, 2020) in a similar way to that of WWII, where food exchange developed as an informal currency (Chavalier, 2016a).

The ‘re-turn’ in the language and action in the food sector generally, exemplified by emergency responses to food production and distribution in the pandemic – led in many cases by CFPs – points, it is argued here, to evidence of social innovation in food drawing from past practice. This issue is now explored more closely empirically.

Community food innovation and the past: empirical evidence

This section describes the rationale for the empirical work that explores the relationship between general food past practice and contemporary food social innovation in CFPs. It then posits an analytical frame through which this relationship is assessed. The methods used are then described, before the results are presented.

Rationale

The empirical exploration of the nature and extent of the way that food social innovation in CFPs draws on the past, has its origins in a study of 2012/2013 of the Brighton and Hove Food Partnership (BHFP – a CFP which is described below). The study (with the title, SOLINSA) had the overall purpose of examining barriers and catalysts to the development of learning and innovation networks for sustainable agriculture. This 2013 research was able to draw conclusions about learning in these innovation networks (Curry and Kirwan, 2014). One unanticipated finding was the extent to which past practice was a strong influence over contemporary social innovation in community food. This overarching re-turn in BHFP was representatively expressed thus in the context of developing an orchard:

“Yes, it is interesting. In many ways it is about rekindling our forgotten past. Some of the things that have happened are about going back to something that we did before, are things that have really sparked huge enthusiasm. For example, the Keep is an archive centre and we managed to get a community orchard planted in the grounds. Local people in that area of Moulsecoomb, a quite deprived council estate, said it reminded them of childhood.

One elderly woman recalled that there was this old apple variety called, um, the Russian White ……. and as part of this orchard, we got the Brighton Permaculture Trust to source the tree for this apple and they planted it. That story went into the press release, and it was one of those things that people got really excited and emotional about. The fact of putting back into the ground, you know this heritage variety that had been around Sussex a long time ago.

That excitement, well, what’s that about? You know, why are people so lit up by that? You know, it’s a kind of nostalgia, but it’s also moving forward to something new, but seemingly familiar. That orchard is all about bringing that community together. It gives the community, including the children, a renewed sense of ownership of the land but also its history. It is very inspiring and offers great potential to these food projects. Great social innovation!”

(BHFP, Interviewee 73, 41:05).

To explore the nature and extent of the use of such past practice in contemporary CFP social innovation further, it was necessary to develop some evidence of ‘the way we used to do things’ in food, as a benchmark. Three sources of evidence were used for this. Firstly, evidence was taken from a study of rural older people – Grey and Pleasant Land (GPL) – that was conducted in 2011. This contained recollections of food practice, particularly in the Second World War, and in the 1930s depression. Secondly, a 2021 case study interview was conducted with a representative of Mrs Smith’s Cottage (MSC), a rural museum with a particular emphasis on food heritage. Both studies are described in the methods section below. Thirdly, data from these two studies, was supplemented with pertinent literature relating to historic food behaviours. Benchmarks drawn from these three sources have the purpose of uncovering historic food practice, that can then be compared to practice within four contemporary CFPs. The full list of empirical sources for this comparison is presented in Table 1.

The analytical frame for this comparison is built around the characteristics of CFPs outlined above. This is their concern to address four market failures (environment, food insecurity, food disadvantage, food-related poor health) a concern for community cohesion and localisation, and their ‘not-for-profit’ mode of operation. Each of these is assessed against historic benchmarking, to inform the extent to which current innovative CFP practice in these areas draws on, or mimics, past practice.

The methods used

Data were drawn from three separate research projects, indicated in Table 1. The contract details of all three are contained in the acknowledgements. The Grey and Pleasant Land (GPL) project was an interdisciplinary exploration of the connectivity of rural elders in rural civic society in England and Wales, which explored themes relating, for example, to trust, belonging and a sense of community. The full fieldwork was carried out in 2009 and involved doorstep face-to-face questionnaire interviews with 150 people of 60 years of age and over in each of six rural areas (900 in total), triggered after an initial approach by post. These were followed up by a series of in-depth semi-structured interviews to pursue issues thrown up by the questionnaire in greater depth. Different interviews were held for different issues, depending on responses, and interviewees were identified through purposive sampling. In these interviews, conversations were encouraged to be steered by participants. These interviews were transcribed before they were reordered thematically.

Two participants in these in-depth interviews were keen to talk about their memories of food and the role that it had to play in ‘community’. They were a married couple, the wife being 93 years old and the husband 92 at the time of the interview. They made direct comparisons between their present-day experiences of food and how things used to be in the 1930s and 1940s. These were seen as periods covering a significant economic depression and the Second World War, both of which were considered by the participants as contributing to the development of ‘close’ communities. The previously unpublished data used here have been extracted from the interview transcript on the basis of specific relevance to food past practice. A full description of the methods used in the study as a whole is contained in Curry and Fisher (2012, 2013).

SOLINSA embraced a case study of the Brighton and Hove Food Partnership (BHFP) CFP, utilising a wide range of methods. A participatory methodology was used (Allen-Collinson et al, 2005) with the co-design and co-development of specific methods agreed between the researchers and participants. These included workshops, mutual learning, world cafes, focus group interviews and desk studies and were executed over a two-year period. As an ‘interpretivist’ approach (Evans et al., 2000) this method commits the researchers to understanding the social world from the perspective of those social actors who inhabit it. It also allows ‘participant-stakeholders’ preferences and needs to inform the research process, leading to what Ostrom (1996) considers are potentially better and more achievable outcomes.

Three members of the research team took an active part in these activities and cumulatively they involved over 100 people involved with BHFP activities. All method forms were active, participatory and involved mutual learning: flows of information and ideas passed from BHFP to the research team and vice versa, with the intention of benefiting both. Following this data-driven, inductive approach, thematic analysis was carried out on the data in order to explore the nature and relevance of the previously unpublished data on ‘learning and innovating from the past’ as portrayed by participants. The research methods for the SOLINSA study are reported fully in Curry and Kirwan (2014).

The NICRE project as a whole was designed to explore the purposes and measures of performance of CFPs. The research approach adopted was that of a practitioner participant observer within a qualitative research frame (Robey and Taylor, 2018), consistent with Gold’s (1958) original consideration of participant observer roles:

“the researcher gains access to a setting by virtue of having a natural and non-research reason for being part of the setting. As observers, they are part of the group being studied” (page 219).

Within this approach, reflective practice was used. Bilous et al. (2018) champion this: it can distil common issues and points of reference, recognisable by practitioners from diverse backgrounds. This ‘insider-researcher’ approach also can elicit a complexity of issues not so apparent in research by ‘outsider’ researchers. Specifically for the exploration of the use of past practice in contemporary practice, in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with three CFPs and a fourth, Sustainable Food Cornwall, provided a written response to the same issues.

Selection criteria required adhering to those purposes of CFPs described above, and case studies were chosen to reflect a range of different CFPs. Consistent with the participant observer research approach, the researchers also had to ensure access to the fieldwork sites; this was granted because of the researcher’s familiarity with each as a member of their respective local food networks. Purposive sampling was used to select the four CFPs, a technique widely used in qualitative research for the identification and selection of information-rich cases, often via a process of ‘snowball sampling’ (Patton, 2002). Specific focus was given in these conversations to the extent to which (if at all) the past influenced actual or aspirational current practice.

For all three projects, ethics approval was secured from each of the University institutional ethics committees through which the research was conducted. Ethics consent forms were agreed by all participants prior to the interviews. For the NICRE research specifically, each participant elected to be identified as follows.

- The coordinator of Sustainable Food Cornwall (SFC).

- The volunteer coordinator and a trustee at Liquorice Park Millennium Green (LPMG).

- A representative of Mrs Smith’s Cottage (MSC).

- The coordinator of Dunston Community Gardening Group (DCGG).

The objectives of each of these CFPs is described in Table 1 and a comprehensive account of the methods used in the NICRE project are contained in Curry (2022).

Results

The results are presented in the order of the analytical frame outlined above. For each characteristic of CFPs, general historical practice is summarised, before observed contemporary CFP practice, explicitly drawing on, or mimicking, past practice, is reported. All quotations from the case studies use the acronym of the organisation followed by the time in the interview at which the quote was offered.

Addressing market failures

CFPs seek to reduce environmental externalities, particularly through reducing food waste and developing lower input-output agriculture. Each of these has parallels in observed historical practice from the benchmarking fieldwork. For example, the rural elders had clear views on how, historically, food waste was kept to a minimum.

“Now, potatoes: we would keep our potatoes in sacks in the shed (in the 1930s) and these would last us all the winter. You can buy a little bag in the supermarket now and they are sprouting within a week before you’ve used them all” (GAPL, M, 10:50).

The local museum provides historical evidence, too, of low input, low output production:

“Despite many changes in ‘productive’ agriculture Mrs Smith resisted most of them. When chemicals and pesticides were becoming much more popular (in the 1950s), she would still grow comfrey and borage to use as pesticides and fertilisers, you know” (MSC, 17:04).

From the fieldwork, these positive environmental actions mirror CFP current practice innovation explicitly referencing historic practice. SFC, for example, is concerned to develop innovative systems of sharing food gluts to reduce waste, making use of traditional methods of preserving and pickling. Low input-output production is deliberate policy on the part of the BHFP, embracing low input impacts on soil, water, biodiversity, and human health. For DCGG, low input innovations are reflexively drawn directly from the past:

“In developing our community growing, I went back to thinking about how my dad did this stuff and just did it how I remember it. Nobody else in the group knew what to do either so we all adopted the same ‘how I remember it’ approach. So we had no sprays and pesticides, which eventually became part of our philosophy” (DCGG 4:56).

The group also has developed an innovative system of cardboard and straw to keep the weeds down and washing up liquid to keep the bugs at bay (DCGG 6.12). For LPMG, low input growing innovations also are seen deliberately as drawing on old ways of doing things:

“In the park, nearly all of what we do is retro. We don’t use chemicals or fertilisers – we have so many volunteers that we can pick weeds by hand. We also do a lot of composting as this is a good way to use green waste from the park. These are traditional methods but that is why they work” (LPMG 10:25).

Tackling food insecurity and food disadvantage also are market failure characteristics that contemporary CFCs seek to tackle. Certainly, in the historic benchmarking, Wartime food deficits were discussed:

“In the War, we used to have to queue for things. If you were in the town one day and somebody said, “oh they’ve got tomatoes up at the fruit stall”, well, everybody made such a dash, you know, to get in the queue for a few tomatoes” (GAPL, F 10:15).

The development of wartime ‘soup kitchens’ (Vorstenbosch et al, 2017), too, has many parallels with contemporary food bank CFPs, as noted above.

Wartime shortages were commonly addressed by foraging (berry and nut picking and mushrooming for manual workers, hunting for the upper classes) (Chavalier, 2016a, pages 237/238) which also is reported as a contemporary innovation in CFPs. Foraging is seen by SFC, for example, as an important means of educating people about ‘free’ food (as well as increasing supply) and in LPMG, foraging is actively managed:

“With the apples …. we put a notice up saying, ‘please take only what you need’ also saying that if they pull, they are ripe but if you have to twist them they are not, so don’t pick them yet” (LPMG, 0:32). “People just come and take herbs, too, as they need them. As long as they are used, anyone can have them” (LPMG, 5:14).

Attention also was paid, from the historical benchmarking, to being ‘careful’ with food, to tackle both insecurity and disadvantage:

“A lot of attention was paid to food storage so that it wouldn’t go bad. Mrs Smith never had a fridge or a freezer. She would either use, give away, or preserve all of her food” (MSC, 10:47).

Food preservation before fridges also was discussed in the GAPL project (GAPL, F, 9:00). Kilner jars would preserve fruits and putting eggs ‘down’ in water glasses would extend the edible life of produce for several weeks. Careful use also is found in contemporary CFPs – although without any explicit reference to past practice. Deliberative harvesting was a social innovation encouraged at DCGG in the context of access to food for all:

“For salad leaves in particular, we encourage anyone (whether they take part in growing or not) to come with a pair of scissors and take what they need for one meal, so that the plant can keep growing – rather than pulling the plants” (DCGG, 13:26).

And making the most of produce at LPMG was also seen as part of innovative learning processes:

“The Polish people who come love the walnuts, for example, and show us how to pickle them (whilst they are still green) and make alcohol from them” (LPMG, 9:08).

Tackling food-related poor health market failures also has historical antecedents. Particularly during Wartime, diets tended to be healthier, it is felt, because of relative food scarcity (Walljasper and Polansek, 2020). Healthier local fresh, pant-based food dominated as other foods were in short supply (Way, 2015) and, according to one GAPL interviewee in the benchmarking fieldwork, this put a natural limit on overeating and therefore being overweight. Food also would be used to promote health. In the 1930s:

“My uncle Alec kept three chickens in the back yard, and they would produce at least one egg a day. When there was more than one, he would give the extra away to someone who was ill” (GPL M 40:20).

But also an understanding of the relationship between food and health was felt by MSC to be greater historically than today:

“Many people today simply don’t know when something is bad to eat. This is knowledge that everyone would have had in the past – when not to drink the milk or eat the butter, for example” (MSC, 11:02).

This lack of understanding was a direct spur to the contemporary development of the BHFP (Interviewee 12). The CFP was instigated by the local heath authority rather than a ‘food’ organisation to provide healthier food within hospitals and also to encourage local food production as a means of educating the local population about the links between food and health. This was considered to be a social innovation: a change in social practice bringing about a positive social improvement.

Such dietary health through education was echoed as an innovation in all of the other CFP evidence. At DCGG, volunteering is considered educative of diets: people come because they want to learn:

“A lot of parents bring their children into the garden to sample varieties of, particularly, salad leaves (we have chard, lambs’ lettuce, rocket, spinach, lettuce, beetroot leaves). This educates them in taste and hopefully will influence their diets” (DCGG, 12:50).

Community cohesion and localisation

CFPs using food to stimulate community cohesion also has historical antecedents. Benchmarking against historical practice, recollections of the GAPL interviewees suggest that working together was part of the natural carry forward from a labour-intensive agriculture in the 1930s and 1940s, of first-generation urban dwellers. MSC, too, stressed the historical communality of the whole of the food chain:

“The village production and allotments were communal, and work and produce both were shared. Particular harvests, for example, apples, would be styled as social events for all to partake. The following month would be taken up with making apple chutney, which also was shared” (MSC, 13:10).

Contemporary innovations in community cohesion also made explicit reference to past practice. In BHFP this is done in relation to reconnecting people with food:

“What is innovative today is the holistic approach to food. This has parallels with 70 years ago, when more people were connected to the soil and knew where their food came from: it was more locally sourced. It is innovative now in that it is much more democratic and about taking control back. In many ways we have been dispossessed over the past 30 years or so of our power over food. This innovation is about getting this power back” (BHFP, Interviewee 41, 27:00).

Community cohesion is seen as an innovative element in all of the other surveyed CFPs as well. Whilst food production is not the primary purpose for LPMG (it is an amenity space) it grows pumpkins and potatoes in order to share them amongst community members (LPMG, 9:57). The principal purpose of DCGG is about making friends in the village. A lot of friendships start in the garden group and then take on a life of their own, illustrating Hinrichs (2000) self-organised connectivity through food, and Cox et al’s (2008) community building through food reconnection. There is an excellent camaraderie particularly amongst men ‘doing things together’ (DCGG, 7:46). SFC’s aims are to bring people together with a shared purpose for learning and enjoyment, and to tackle rural isolation.

Localising food also has direct historical parallels. In terms of benchmarking, the GAPL rural elders referred to back garden produce and local allotments in both the 1930s and 1940s as the cornerstone of food supply. This reflects the Second World War, where over half of manual workers in a mid-War survey had a garden or a plot, public parks were converted in London, and nationally some 500,000 new allotments were announced on such land in 1940 (Chavalier, 2016a: 57, 58).

Localness is seen as innovative in all of the fieldwork CFPs. More than 200 local food growing groups are members of the BHFP and the City Council has allocated more allotment land as a result. DCGG came into being to tidy up the local public curtilage of the village hall through vegetable and flower planting (DCGG, 3:54). Localness, as with community, in cases also is explicitly related to the past:

“This (emphasis on community and localness) of course, has been done before … throughout Europe during the war, for example, where food was grown in public spaces, so it’s not actually new but it is new now to the collective consciousness out here in Brighton and Hove, and we find that quite exciting” (BHFP, Interviewee 73 12:15).

And ’learning how to be local’ explicitly relied on past practice at LPMG, too:

“It’s difficult to know where to go to learn about how to do local food growing in this kind of communitarian low intensity way. Most agricultural colleges are very ‘commercial’ and are about high intensity production. Here we tend to learn mainly through remembering what our parents and grandparents did. This then becomes a process of mutual learning because a range of us turn up to the Park today with a broad range of different remembered skills” (LPMG, 15:05, 18:27).

Not for profit

There are historical antecedents in the ‘not-for-profit’ behaviours in CFPs, too. Historical benchmarks are readily available from the Second World War where food exchange took place largely outside of monetary exchange (Chavalier, 2016b). Regular food reciprocity was common (page 179) with different types of food having different ‘currency’ values, even extending to non-food exchange. But even before the War in the 1930s, GAPL interviewees emphasised non-monetary trading.

“Yes, but my father used to give a lot of his vegetables away, usually to the extended family, because he needed the space to grow more vegetables. If you didn’t give them away, you just wasted them” (GAPL, F 5:25).

And into the 1950s, non-monetary exchange was also observed historically by the food museum, in food production:

“Food production didn’t require much investment. People would borrow things from each other, and they worked to produce food as a community so that nobody would have to pay for everything” (MSC, 8:43).

This commonly was triggered by a desire to enhance social cohesion, for example, working together on the land, sharing ideas about different seed varieties, or more simply sharing food or ‘gifting’ it to others (MSC, 9:37).

This link between ‘not-for-profit’ and ‘community’ is replicated in the contemporary context. For the BHFP, non-monetary exchanges are seen as part of their social innovation. Vegetable boxes can be ‘purchased’ by working a number of hours on the allotment. The BHFP seed exchange project, ‘Seedy Sunday’, also operates as a non-monetary exchange. At LPMG, too, strong communities where people trust each other (LPMG, 20:07) allows barter:

“All of the produce that comes from the Park is either gifted or bartered. Some people might make a donation for it in order that we can buy tools and the like but this is not a price for the food, it’s a kind of barter – food for a fork or a spade” (LPMG, 19:20).

At DCGG this ‘not-for-profit mode’ is also inextricably linked with localness:

“The food from the village hall grounds goes on a table with a donations tin and people can then help themselves. People are usually very generous financially, contributing to the cause as well as paying for the food (DCGG, 10:04). More recently, people have been bringing surplus from their own gardens to leave on the table too. This has a cumulative impact on food sharing” (DCGG, 15:15).

Discussion

These empirical findings inform, from past practice, general operational actions available to contemporary CFPs. They also lend legitimacy to the argument that the past can have a meaningful role to play in developing theories of contemporary social innovation, certainly in the food domain. The findings are an important contribution to food actions and policy as the community food sector grows to counter global monopolistic and distant agri-food systems, with their inherent market failures. This community food growth is served well through drawing on past practices, as they took place before globalisation gained such momentum.

In respect of addressing market failures, drawing on past practice offers operational examples of ‘intermediate technologies’ and ‘forgotten practices’ that serve a range of environmental purposes well, in addition to addressing a range of food insecurities through past practices in storage and distribution methods. Reconnecting people with food, too, can have a positive impact on food-related health education.

Lessons from the past in terms of food localisation and community cohesion also have a valuable role to play in current practice. Effective mechanisms of local food exchange (in production, processing, and consumption) and traditions of food cooperation, collaboration and volunteering all hold a useful mirror to contemporary community food practices.

In terms of social innovation, too, many CFPs assert their innovative nature, but also acknowledge the significance of developing old ideas in new contexts. Many ‘new’ community practices are acknowledged as not being new (for example, low chemical inputs, working collectively, food sharing). These are, rather, adapted from the old.

Such use of past practices, it is argued here, is not mere nostalgia, but rather a critical assessment and adaptation into a contemporary context of the way we used to do things. Drawing on the past allows the accommodation of a wealth of experience (wisdom as well as knowledge), rather than a reliance simply on the ‘new’ – which commonly entails higher risks that can lead to development vertigo.

Conclusions

This paper has been concerned to explore the extent to which the purposes and innovative actions of CFPs are informed by past practice. As an area that has hitherto received little attention, there is clear empirical evidence that contemporary CFP innovation is both explicitly informed by past practice and more pervasively, also mimics it, wittingly or not. This lends legitimacy to using the way that food used to be ‘done’ as an evaluative sieve, to interrogate Shove’s (2010) ‘forgotten’ practices, and Pickering and Keightley’s (2006) ‘the way we used to do things’ as a novel contribution to understanding contemporary theories of social innovation.

Using such an evaluative sieve in this way throws light on how the past can inform innovation in the context of contemporary food problems, and the mechanisms that can be used to achieve them at the community level. That innovation in food systems should be founded on sound historical practice is now a clear recommendation of the National Food Strategy for England (Dimbleby, 2021). This is lent weight by an increasing interest in the ‘re-turn’ advocated in much food policy writing. Regenerative agriculture that allows resource restoration and resilience is advocated alongside food relocalisation for both community and environmental ends.

But the adoption of past methods should not be indiscriminate. A close study of historical food practices as a critical learning experience, can allow their adaptation as well as their adoption. And in terms of social innovation, such a study of historical practice can do much to inform about those things that might also be avoided in the operation of contemporary CFPs, as well as taken up.

This paper draws on three research projects. The first, Support for Learning and Innovation Networks in Sustainable Agriculture (SOLINSA), funded by the Seventh Framework Programme of the European Commission, ran between February 2011 and January 2014. The second, Economic Performance in Rural Systems: Social Collision Theory and Its Application to Rural Food Hubs, running in 2021, received funding from the National Innovation Centre for Rural Enterprise. The third, Grey and Pleasant Land?: an Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Connectivity of Older People in Rural Civic Society, was funded by the Research Councils under the New Dynamics of Ageing Programme. It ran from 2008 – 2012 and included an exploration of community values surrounding food.

Much gratitude also is expressed to two anonymous referees for very helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Nigel Curry, College of Social Science, University of Lincoln, Brayford Campus, Lincoln, LN6 7TS. Email: nrcurry@hotmail.com

Adams, D. and Hess, M. (2008) Social innovation as a new public administration strategy. Proceedings of the 12th annual conference of the International Research Society for Public Management. 26–28 March 2008. Brisbane, pp. 1–8.

Adger, N. (2000) Social and Ecological Resilience: Are they Related? Progress in Human Geography, 24, 3, 347–364. CrossRef link

Allen, E. (2012) The good food story, Museums and Social Issues, 7, 1, 23-28. CrossRef link

Allen-Collinson, J., Fleming, S., Hockey, J. and Pitchford, A. (2005) Evaluating sports-based inclusion projects: methodological imperatives to empower marginalised young people. In: K Hylton, J Long, and A Flintoff (eds) Evaluating Sport and Active Leisure for Young People. Eastbourne: LSA: 45-59.

Beckie, M.A., Huddart, E. and Wittman, H. (2012) Scaling up alternative food networks: Farmers’ markets and the role of clustering in western Canada. Agriculture and Human Values, 29, 333–345. CrossRef link

Berti, G. and Mulligan, C. (2016) Competitiveness of small farms and innovative food supply chains: The role of food hubs in creating sustainable regional and local food systems. Sustainability, 8, 616. CrossRef link

Bilous, R. H., Hammersley, L. and Lloyd, K. (2018) Reflective practice as a research method for co-creating curriculum with international partner organisations. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 19, 3, 287-296.

Blay-Palmer, A., Landman, K., Knezevic, I. and Hayhurst, R. (2013) Constructing resilient, transformative communities through sustainable “food hubs”. Local Environment, 18, 521–527. CrossRef link

Bourdieu, P. (1977) Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. CrossRef link

Burstrom, M. (2021) Affects: sensing things. In: Olsen, B., Burström, M., DeSilvey, C. and Pétursdóttir, P. (eds) After discourse: things, affects, ethics. London: Routledge. CrossRef link

Callon, M. (2007) What does it mean to say that economics is performative? In: Mackenzie, D., Muniesa, F. and Siu, L. (eds) Do economists make markets? Princeton: Princeton University Press: 311-357. CrossRef link

Chavalier, N. (2016a) ‘Rationing has not made me like margarine’. Food and the Second World War in Britain: A mass observation testimony. Doctoral thesis (PhD), University of Sussex.

Chavalier, N. (2016b) From eating by necessity to rather do without: Food habits, social classes, and wartime food situation in Britain. In: Baho, S. and Katsas, G. (eds) Making sense of food: Exploring cultural and culinary identity. Sussex: Inter Disciplinary Press.

Chiffoleau, Y. and Dourian, T. (2020) Sustainable food supply chains: Is shortening the answer? A literature review for a research and innovation agenda. Sustainability, 12, 23, 9831. CrossRef link

Collingham, L. (2011) The taste of the war: World War Two and the battle for food. London: Allen Lane.

Cox, R., Kneafsey, M., Venn, L., Holloway, L., Dowler, E. and Tuomainen, H. (2008) Constructing sustainability through reconnection: The case of ‘alternative’ food networks. In: Robinson G. (ed) Sustainable rural systems: Sustainable agriculture and rural communities. London: Routledge.

Crabtree, T., Morgan, K. and Sonnino, R. (2012) Prospects for the future: Scaling up the community food sector: Making Local Food Work. Woodstock, The Plunkett Foundation. Available at: https://is.muni.cz/el/fss/jaro2022/ENSn4656/um/Prospects_for_Future_report-1.pdf

Curry, N.R. (2022) Working collaboratively through rural community food hubs, Research report number 8. National Innovation Centre for Rural Enterprise, June.

Curry, N.R. and Fisher, R. (2012) The role of trust in the development of connectivities amongst rural elders in Britain. Journal of Rural Studies, 28, 4, 358–370. CrossRef link

Curry, N.R. and Fisher, R. (2013) Being, belonging and bestowing: differing degrees of community involvement amongst rural elders in England and Wales. European Journal of Ageing, 10, 4, 325–333. CrossRef link

Curry, N.R. and Kirwan, J. (2014) The role of tacit knowledge in the development of sustainable agriculture. Sociologia Ruralis, 54, 3, 341–361. CrossRef link

Curry, N.R. and Purle, K. (2021) A social economy strategy for greater Lincolnshire 2021 – 2031: research report. Lincoln: Bishop Grosseteste University, Lincoln. Available at: https://s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/bishopg.ac.uk/documents/loric-knowledge/LORIC-Social-Economy-Research-Report-Access.pdf

Dimbleby, H. (2021) National Food Strategy, the plan, and Independent Review. Available at: https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org

Dowler, E. and Caraher, M. (2003) Local food projects: The new philanthropy? The Political Quarterly, 74, 1, 57-65. CrossRef link

Dwivedi, S.L., Lammerts van Bueren, E.T., Ceccarelli, S., Grando, S., Upadhyaya, H.D. and Ortiz, R. (2017) Diversifying food systems in the pursuit of sustainable food production and healthy diets. Trends in Plant Science, 22, 10, 842-856. CrossRef link

European Commission (2014) Social Innovation. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/industry/strategy/innovation/social_en

Evans, L., Hardy, L. and Fleming, S. (2000) Intervention strategies with injured athletes: an action research study. The Sport Psychologist, 14, 2, 188–206. CrossRef link

Facchini, E., Lacovidou, E., Gronow, J. and Voulvoulis, N. (2018) Food flows in the United Kingdom: The potential of surplus food redistribution to reduce waste. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 68, 9, 887–899. CrossRef link

Fardkhales, A.S. and Lincoln, N. K. (2021) Food hubs play an essential role in the COVID-19 response in Hawai‘i. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 10, 20, 53–70. CrossRef link

Feagan, R. (2007) The place of food: Mapping out the local in local food systems. Progress in Human Geography 31, 1, 23–42. CrossRef link

Geels, F. W. and Schot, J. (2007) Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy, 36, 399–417. CrossRef link

Giller, K.E., Hijbeek, R. and Andersson J.A. (2021) Regenerative agriculture: An agronomic perspective. Outlook on Agriculture, 50, 1, 13–25. CrossRef link

Gold, R. (1958) Roles in sociological field observation. Social Forces, 36, 217-213. CrossRef link

González-Ruibal, A. (2021) What remains? On material nostalgia. In: Olsen, B., Burström, M., DeSilvey, C. and Pétursdóttir, P. (eds) After discourse: Things, affects, ethics. London: Routledge. CrossRef link

Grasseni, C. (2014) Family farmers between re-localisation and co-production. Anthropological Notebooks, 20, 3, 49–66.

Guerlain, M.A. and Campbell, C. (2016) From sanctuaries to prefigurative social change: Creating health-enabling spaces in East London community gardens. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 4, 1, 220-237. CrossRef link

Hargreaves, T., Longhurst, N. and Seyfang, G. (2013) Up, down, round and round: connecting regimes and practices in innovation for sustainability. Environment and Planning, 45, 402–420. CrossRef link

Henry, R. (2020) Innovations in agriculture and food supply in response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Molecular Plant, 13, 1095–1097. CrossRef link

Hinrichs, C. C. (2000) Embeddedness and local food systems: Notes on two types of direct agricultural market. Journal of Rural Studies, 16, 3, 295–303. CrossRef link

Jones, R., Lane, E. and Prosser, L. (2019) Marketing the markets – supporting re-localisation of rural food economy through facilitation of local producer markets. RGS-IBG Conference, 20 August.

Klerkx, L. and Leeuwis, C. (2009) Technological forecasting & social change establishment and embedding of innovation brokers at different innovation system levels: Insights from the Dutch agricultural sector. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 76, 849–860. CrossRef link

Lal, R. (2020) Home gardening and urban agriculture for advancing food and nutritional security in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Security, 12, 871- 876. CrossRef link

Lambie-Mumford, H. (2019) The growth of food banks in Britain and what they mean for social policy. Critical Social Policy, 39, 1, 3-22. CrossRef link

Lang, T. (2020) Feeding Britain: Our food problems and how to fix them. London: Pelican.

Lawson, L.J. (2005) City bountiful: A century of community gardening in America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Le Blanc, J.R., Conner, D., Mcrae, G. and Darby, H. (2014) Building resilience in non-profit food hubs. Journal of Agricultural Food Systems and Community Development, 4, 121–135. CrossRef link

Lindgren, E., Harris, F., Dangour, A.D., Gasparatos, A., Hiramatsu, M., Javadi, F., Loken, B., Murakami, T., Scheelbeek, P. and Haines, A. (2018) Sustainable food systems – a health perspective. Sustainability Science, 13, 1505-1517. CrossRef link

Lupton, D. (1996) Food, the body and the self. London: Sage.

Matson, J., Sullins, M. and Cook, C. (2013) The role of food hubs in local food marketing. Rural Development Service Report 73. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Agriculture. CrossRef link

McKeon, N. (2015) Food security governance: Empowering communities, regulating corporations. London: Routledge.

McLain, R.J., Hurley, P.T., Emery, M.R. and Poe, M.R. (2014) Gathering “wild” food in the city: rethinking the role of foraging in urban ecosystem planning and management. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 19, 2, 220–40. CrossRef link

Newton, P., Civita, N., Frankel-Goldwater, L., Bartel, K. and Johns, C. (2020) What is regenerative agriculture? A review of scholar and practitioner definitions based on processes and outcomes. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 26 October. CrossRef link

Nicholls, A., Simon, J. and Gabriel, M. (2015) New Frontiers in Social Innovation Research. London, Palgrave Macmillan. Open Source. Available at: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/27885/1002117.pdf?sequence=1

Nyström, H. (2013) The postmodern challenge: from economic to creative management. in Fuglsang, L. and Sundbo, J. (ed) Innovation as Strategic Reflexivity, Routledge advances in Management and Business Studies. London: Rutledge.

Ostrom, E. (1996) Crossing the great divide: Co-production, synergy and development. World Development, 24, 6, 1073–1088. CrossRef link

Pantzar, M. and Shove, E. (2010) Understanding innovation in practice: a discussion of the production and re-production of Nordic walking. Technological Analysis and Strategic Management, 22, 447–461. CrossRef link

Papargyropoulou, E., Lozano, R., Steinberger, J.K., Wright, N. and bin Ujang Z. (2014) The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. Journal of Cleaner Production, 76, 106-115. CrossRef link

Patton, M. Q. (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pearson, D.H. and Firth, C. (2012) Diversity in community gardens: Evidence from one region in the United Kingdom. Biological Agriculture & Horticulture, 28, 3, 147-155. CrossRef link

Pickering, M. and Keightley, E. (2006) The Modalities of Nostalgia. Current Sociology, 54, 6, 919–941. CrossRef link

Post Carbon Institute (2021) What is relocalisation? Available at: https://www.postcarbon.org/relocalize/

Power, M., Doherty, B., Pybus, K.J. and Pickett, K.E. (2020) How COVID-19 has exposed inequalities in the UK food system: The case of UK food and poverty. Emerald Open Research, 2, 11. CrossRef link

Psarikidou, K., Kaloudis, H., Fielden, A. and Reynolds, C. (2019) Local food hubs in deprived areas: De-stigmatising food poverty? Local Environment, 24, 6, 525-538. CrossRef link

Public Health England (2016) Lifestyle and behaviours. Available at: http://www.noo.org.uk/NOO_about_obesity/lifestyle

Reckwitz, A. (2002) Toward a theory of social practices: a development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 52, 243–263. CrossRef link

Renting, H., Marsden, T.K. and Banks, J. (2003) Understanding alternative food networks: Exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environment and Planning A, 35, 393–411. CrossRef link

Rip, A. and Kemp, R. (1998) Technological change. In: Rayner, S., and Malone, E.L. (eds), Human Choice and Climate Change. Columbus, OH, Battelle Press, 327–399.

Robey, D. and Taylor, W.W.F. (2018) Engaged participant observation: An integrative approach to qualitative field research for practitioner- scholars. Engaged Management Review, 2, 1. CrossRef link

Rogers, E.M. (2004) A prospective and retrospective look at the diffusion model. Journal of Health Communication: International Perspectives, 9, 1, 13–19. CrossRef link

Røpke, I. (2009) Theories of practice—new inspiration for ecological economic studies on consumption. Ecological Economics, 68, 2490–2497. CrossRef link

Rosaldo, R. (1993) Culture and truth: The remaking of social analysis. London: Routledge.

Rose, N. (2017) Community food hubs: an economic and social justice model for regional Australia? Rural Society, 26, 3, 225–237. CrossRef link

Seekell, D., Carr, J., Dell’Angelo, J., D’Odorico, P., Fader, M., Gephart, J., Kummu, M., Magliocca, N., Porkka, M., Puma, M., Ratajczak, Z., Rulli, M.C., Suweis, S. and Tavoni, A. (2017) Resilience in the global food system. Environmental Research Letters, 12. CrossRef link

Seyfang, G. and Haxeltine, A. (2012) Growing grassroots innovations: Exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Environment and Planning C, 30, 381–400. CrossRef link

Shove, E. (2010) Beyond the ABC: climate change policy and theories of social change. Environment and Planning A, 42, 1273–1285. CrossRef link

Shove, E. and Walker, G, (2010) Governing transitions in the sustainability of everyday life. Research Policy, 39, 471–476. CrossRef link

Smith, A. (2012) Civil society in sustainable energy transitions. In: Verbong, G. and Loorbach, D. (eds) Governing the energy transition: Reality, illusion or necessity? London, Routledge: 180–202.

Stevenson, G. and Pirog, R. (2008) Values-based supply chains: Strategies for agri-food enterprises of the middle. In: Lyson, T., Stevenson, G., Welsh, R., (eds) Food and the mid-level farm: Renewing an agriculture of the middle. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. CrossRef link

Stroink, M.L. and Nelson, C.H. (2013) Complexity and food hubs: Five case studies from Northern Ontario. Local Environment, 18, 620–635. CrossRef link

Tendall, D. M., Joerin, J., Kopainsky, B., Edwards, P., Shreck, A., Le, Q. B. and Six, J. (2015) Food system resilience: defining the concept. Global Food Security, 6, 17–23. CrossRef link

Vorstenbosch, T., deZwarte, I., Duistermaat, L. and van Andel, T. (2017) Famine food of vegetal origin consumed in the Netherlands during World War II. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 13, November. CrossRef link

Walljasper, C. and Polansek, T. (2020) Home gardening blooms around the world during Coronavirus lockdowns. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-gardens-idUSKBN2220D3

Watts, D.C.H., Ilbery, B. and Maye, D. (2005) Making reconnections in agro-food geography: Alternative systems of food provision. Progress in Human Geography, 29, 1, 22–40. CrossRef link

Way, T. (2015) The wartime garden. Oxford: Shire Publications.

Weber, H., Poeggel, K., Eakin, H., Fischer, D., Lang, D. J., Von Wehrden, H. and Wiek, A. (2020) What are the ingredients for food systems change towards sustainability? Insights from the literature. Environmental Research Letters, 15, 11, October, 131001. CrossRef link

Winter, M. (2003) Geographies of food: Agrofood geographies – making connections. Progress in Human Geography, 27, 505–13. CrossRef link

Yarnit, M. (2021) Time to invest in local food hubs. Sustain, blogs: food and farming policy. London: Sustain. Available at: https://www.sustainweb.org/blogs/feb21-food-hubs/