Abstract

Intra-organisational communication is central to sustaining participation, cohesion, and legitimacy in voluntary organisations, yet systematic tools for analysing leadership communication in such contexts remain underdeveloped. This article makes a methodological contribution by developing and demonstrating a theory-informed codebook for the systematic study of leadership communication in grassroots political organisations. Combining structured content analysis with reconstructive-hermeneutic interpretation, the approach integrates transparency and replicability with interpretive depth. The empirical material consists of two written communications produced during a critical moment of intra-organisational deliberation. Treated as critical incidents, these texts condense tensions around authority, cohesion, and legitimacy and serve as analytically rich exemplars for method demonstration. The resulting six-cluster framework encompasses 1) Social influence strategies, 2) Role and power communication, 3) Emotion regulation, 4) Legitimacy construction, 5) Cohesion strategies, and 6) Collective identity appeals. Iterative coding and refinement yielded eight interpretive propositions that illustrate how authority is procedurally constructed, legitimacy anchored in both rules and participation, and cohesion restored through affective regulation and identity appeals. The article’s primary contribution lies in offering a replicable analytical tool that bridges theory and qualitative data by mapping communicative segments to higher-order propositions. Methodologically, the framework demonstrates how qualitative coding can move beyond descriptive categorisation to generate transferable insights into fragile authority structures. While empirically modest, the study provides a structured and adaptable instrument for future research across participatory contexts. By conceptualising the codebook as a boundary object, it supports cumulative theorising and offers a foundation for comparative studies of leadership communication in voluntary organisations.

Introduction

Intra-organisational communication within grassroots organisations constitutes a critical mechanism for sustaining participation, cohesion, and resilience (Hansen & Hau, 2024; Liu et al., 2025; Trent et al., 2020). Yet voluntary and grassroots groups increasingly confront challenges of trust, retention, and legitimacy, particularly under conditions of uncertainty or conflict (Croissant & Lott, 2025; Della Porta, 2020; Holloway & Manwaring, 2023; Vestergren et al., 2019). These challenges are not only internal: they affect the ability of voluntary organisations to act as anchors of civic participation and as sources of democratic resilience (Ansell et al., 2023; Ardoin et al., 2023). Earlier scholarship emphasised leadership and authority in formal political institutions and bureaucratic contexts (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Katz & Kahn, 1978; Scarrow et al., 2017), but micro-level analyses of communicative practices in volunteer-based organisations remain scarce (Morrison & Greenhaw, 2018). This gap is particularly evident with regard to the affective, relational, and procedural dimensions of communication, which recent research increasingly recognises as vital to the functioning and legitimacy of civil society organisations (Crevani et al., 2010; Jasper, 1998; Ospina et al., 2020; Raelin, 2022).

The absence of clear analytical frameworks for studying leadership communication in voluntary organisations presents two interrelated problems. First, existing studies rarely provide a replicable method for identifying how authority, legitimacy, and cohesion are enacted in day-to-day communication. While discourse-oriented studies offer valuable interpretive insights (Fairhurst & Connaughton, 2014), they often lack transparent coding protocols that would allow for cumulative and comparative research. Second, affective and identity-related dynamics – such as emotional regulation, empathy, or collective goal affirmation – remain under-analysed, despite their importance for sustaining participation in contexts where authority is fragile and membership is voluntary (Jasper, 1998; Vestergren et al., 2019). This study addresses both limitations by developing and demonstrating a theory-informed codebook for the systematic analysis of leadership communication in decentralised, participatory settings.

The article positions itself as a methodological contribution. Rather than reporting extensive empirical findings, its primary aim is to design and validate a replicable framework that captures how authority, legitimacy, emotional regulation, and collective identity are communicatively negotiated in everyday organisational life. In doing so, it responds directly to recent calls for more rigorous tools to study the micro-foundations of democratic resilience in civic and grassroots organisations (Bazeley, 2021; Della Porta, 2020; Ospina et al., 2020).

The codebook was developed through a four-phase process that integrates structured content analysis (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2024) with reconstructive-hermeneutic interpretation (Bohnsack, 2014). This dual approach balances transparency and comparability with interpretive depth. Structured coding ensures auditability and replicability, while hermeneutic reconstruction makes it possible to surface latent meanings, role tensions, and collective narratives. The empirical material consists of two written communications authored during a critical phase of intra-organisational deliberation. Treated as critical incidents (Tripp, 2011), these texts illuminate tensions around authority, legitimacy, and cohesion at a moment of organisational strain. While modest in number, their interpretive density makes them analytically sufficient for demonstrating the framework’s value (Small, 2009). The study does not claim statistical representativeness; its contribution lies in offering a methodological demonstration of how systematic coding can generate transferable insights.

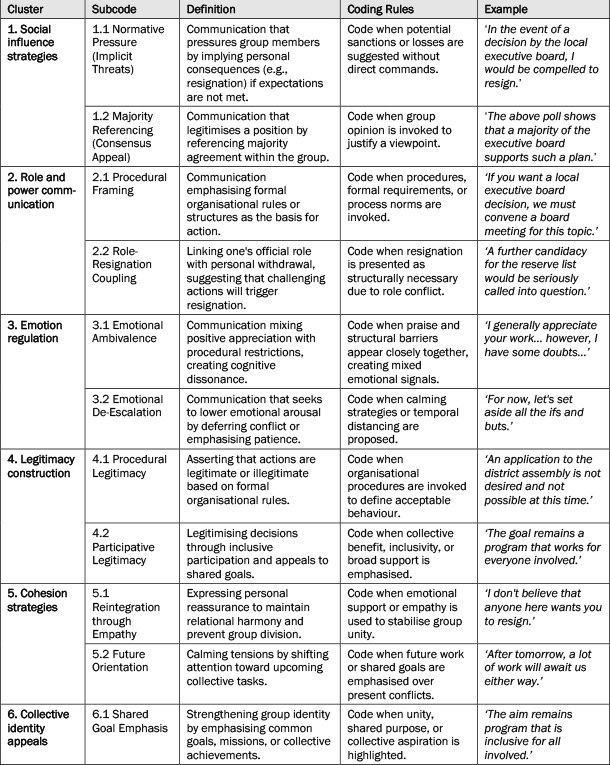

The resulting coding scheme identifies six dimensions of leadership communication in voluntary organisations. Each is grounded in established theory but refined through iterative engagement with the empirical material. Social Influence Strategies; Drawing on persuasion theory (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004), this captures attempts to mobilise compliance in the absence of hierarchy, including subtle normative pressure and appeals to majority opinion. Role and Power Communication; based on role theory (Goffman, 1959; Yukl, 2013), this dimension reflects how authority is constructed or challenged through references to roles, procedures, and the implicit threat of withdrawal. Emotion Regulation; building on research on emotional labour and political psychology (Goleman, 2006; Marcus et al., 2008), this captures strategies to manage tension, express ambivalence, or de-escalate conflict – key in organisations reliant on affective commitment. Legitimacy Construction; following organisational legitimacy theory (Suchman, 1995), this highlights how communicative acts justify positions procedurally (via rules) or participatively (via inclusivity and collective will). Cohesion Strategies; grounded in small-group psychology (Forsyth, 2019), this covers communicative moves that prevent fragmentation and maintain solidarity, such as reintegration after conflict or future-oriented reassurance. Collective Identity Appeals; informed by social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), this dimension captures how shared goals and collective aspirations are affirmed to strengthen group identity. Together, these six dimensions provide an integrated lens for analysing how micro-level communicative acts both structure immediate interaction and shape broader organisational processes of resilience, legitimacy, and identity construction.

By articulating these dimensions into an operational framework, the paper advances methodological discussion and supplies a tool that is both replicable and adaptable. Its contribution lies in offering a transparent approach for future qualitative research into leadership communication in volunteer-based organisations, thereby strengthening analytical rigour and supporting theory-informed generalisation. Beyond methodology, the framework also lays the groundwork for examining the communicative micro-foundations of participation, cohesion, and democratic resilience in civil society.

The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 outlines the methodological procedures, including data selection, codebook construction, and reflexivity. Section 3 presents the coding protocol and analytical principles. Section 4 introduces interpretive propositions derived from the coded material, illustrating how the framework generates insights. Section 5 summarises the final coding structure, with supplementary material providing detailed definitions and examples. Section 6 discusses the theoretical contribution, practical relevance, and potential transferability of the framework to other participatory contexts.

Method

This study advances a codebook for examining leadership communication in volunteer-based political organisations. The design integrates structured content analysis (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2024), ensuring transparency and replicability, with reconstructive-hermeneutic interpretation (Bohnsack, 2014), which surfaces underlying meanings, role tensions, and collective narratives. Situated within a constructivist–interpretivist paradigm but attentive to the social embeddedness of texts, the approach positions the codebook as both a systematic instrument and a generative framework for theorising communicative practices in participatory settings.

Data collection & case selection

The empirical material consists of two written communications produced during a preparatory phase of internal deliberation in a volunteer-based political organisation in a mid-sized European municipality. Although limited in number, these texts were selected through theoretical sampling (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) as paradigmatic cases (Flyvbjerg, 2006). They qualify as critical incidents (Tripp, 2011), in which underlying conflicts of legitimacy, authority, and cohesion were condensed in explicit form. Their interpretive density renders them analytically sufficient for demonstrating a coding framework, particularly in exploratory and methodological work (Mason, 2010; Small, 2009). The two texts should thus not be read as representing the entirety of grassroots organisational discourse but as empirically grounded exemplars that provide a suitable basis for generating a transferable, theory-informed codebook (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2018). Access to the data set was granted through the researcher’s legitimate organisational role (Salmons, 2017).

Codebook development

The codebook was developed through a four-phase process based on the principles of structured content analysis (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2024), combining theory-driven category development with iterative empirical refinement. This ensured both theoretical alignment and responsiveness to the material.

- Phase 1 – Deductive framework construction: Following Kuckartz and Rädiker (2024), core analytical clusters were derived from established theoretical domains: Social Influence Strategies (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004), Role and Power Communication (Goffman, 1959; Yukl, 2013), Emotion Regulation (Goleman, 2006), Legitimacy Construction (Suchman, 1995), Cohesion Strategies (Forsyth, 2019), and Collective Identity Appeals (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). These clusters were defined as analytically distinct, with conceptual boundaries clarified to avoid overlap: for instance, legitimacy concerns institutionalised justification, whereas cohesion refers to intra-group affective bonds.

- Phase 2 – Initial coding and empirical immersion: The texts were segmented and deductively coded in MAXQDA 2024. Memos documented interpretive decisions, overlaps, and emerging tensions beyond surface categorisation, ensuring hermeneutic depth alongside procedural rigour.

- Phase 3 – Inductive refinement and subcategory formation: Subcategories were inductively derived to capture nuances absent from theory, including role-resignation coupling, emotional ambivalence, and majority referencing. A double-coding protocol was applied to reflect multifunctional utterances, ensuring that communicative complexity was preserved. This step was undertaken collaboratively with a second researcher from the same academic field, under the author’s supervision.

- Phase 4 – Consolidation and validation: Categories and definitions were refined, exemplary passages assigned, and interpretive propositions derived. Informal peer debriefings with a colleague outside the coding team were used to test plausibility and transparency. The resulting codebook balances theoretical alignment with empirical sensitivity, ensuring transferability to broader datasets.

Coding procedure and analytical principles

The unit of analysis was defined as the smallest self-contained segment conveying a distinct communicative function (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2024). Segments were coded according to their pragmatic intent and relational positioning, not merely surface wording (Krippendorff, 2013). Coding rules were documented in a log, providing an audit trail for transparency. Double coding preserved multifunctionality (Coulston et al., 2025), while memo-writing supported reflexive engagement and the articulation of emergent insights. Although no formal intercoder reliability statistic was calculated due to the small dataset, joint calibration sessions and consensus-building discussions were employed as informal reliability measures (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). For larger applications of the codebook, established intercoder reliability protocols are recommended.

Researcher position and reflexivity

The researcher’s embeddedness in the organisation provided legitimate access and contextual insight into leadership dynamics (Salmons, 2017). The researcher held a non-executive membership role without decision-making authority, ensuring proximity without positional power (Riese, 2019). While this positioning offered interpretive depth, it also carried risks of bias and reduced analytical distance (Mercer, 2007). Reflexive strategies were therefore systematically employed (Alvesson, 2003; Dwyer & Buckle, 2009). Reflexive memos documented tensions between insider knowledge and analytical distance (Mahbub, 2017). Informal peer debriefings and calibration sessions further validated interpretations and mitigated subjectivity. A documented audit trail and structured codebook enhanced transparency and trustworthiness (Bazeley, 2021; Miles et al., 2020). In this way, embeddedness was treated as an epistemic resource while maintaining critical reflexivity (Chavez, 2015; Hellawell, 2006).

Ethical considerations

The study followed ethical guidelines for low-risk qualitative research (British Sociological Association, 2017; Creswell & Poth, 2025). It involved no direct participant interaction, deception, or collection of sensitive personal data (British Sociological Association, 2017). Informed consent was obtained for the use of all written material (University of Oxford, 2022). Data were processed in line with GDPR (European Commission, 2018), and identifying information – such as names, places, or organisational references – was paraphrased or removed. Raw data will not be publicly shared. All reporting preserves confidentiality and respects the dignity of those involved.

Result

The structured content analysis yielded a six-cluster framework that captures central communicative mechanisms in volunteer-based political organisations. Across clusters, recurrent tensions became visible: authority was consistently negotiated through references to formal procedures and implicit sanctions, legitimacy was anchored in both procedural correctness and collective participation, and cohesion was maintained through a mixture of emotional regulation and appeals to shared identity. These tensions crystallised into eight interpretive propositions that synthesise how leadership communication stabilises or destabilises voluntary organisations. Rather than operating in isolation, the propositions reflect overlapping mechanisms, showing that authority, legitimacy, and cohesion are not discrete categories but dynamically intertwined in communicative practice.

Six-cluster coding framework

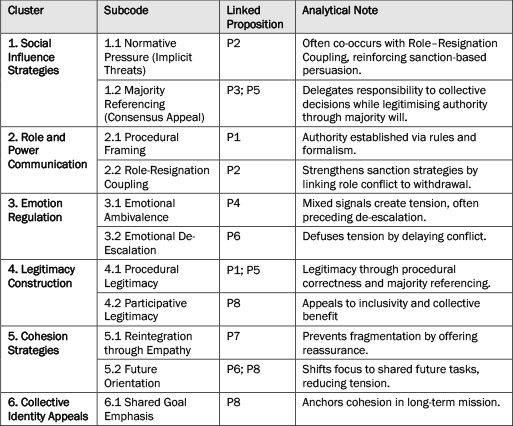

The final framework consists of six clusters with corresponding subcodes, operational definitions, coding rules, and exemplary segments (Table 1). Developed deductively from established theory and refined inductively through iterative engagement with the material, the framework captures communicative practices ranging from procedural framing and implicit threats to empathy-based reintegration and identity appeals. Each subcode was systematically linked to one or more of the interpretive propositions, ensuring transparency between textual evidence and higher-order generalization (Table 2).

The complete codebook – including definitions, coding instructions, and exemplary segments – is available at the Zenodo open-access repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16759245

Mapping codes to interpretive propositions

To ensure analytical transparency, subcodes were linked to eight interpretive propositions. These propositions (P) condense recurring patterns into ideal-typical communicative mechanisms. (Table 2).

Authority construction through procedural framing (P1) emerged most clearly from the Role and Power Communication cluster, where procedural references consistently positioned formal rules as the foundation of legitimacy. This strategy stabilised leadership by reducing contestation to questions of rule compliance. Reinforcement of authority was further visible in normative pressure via implicit threats (P2), derived from the co-occurrence of Normative Pressure (Implicit Threats) and Role–Resignation Coupling. Here, the prospect of withdrawal translated individual role conflicts into collective risks, compelling alignment without overt coercion. Patterns of delegating accountability to the group (P3) were captured in Majority Referencing, which displaced responsibility onto collective decisions and positioned the group itself as the ultimate locus of legitimacy. Yet these procedural and normative moves often generated tension. Emotional ambivalence and cognitive dissonance (P4) arose from overlaps between Emotional Ambivalence codes and concurrent expressions of appreciation and critique, producing destabilising but also regulative dynamics within the group. Legitimacy was not anchored in one domain alone. Legitimisation through dual anchoring (P5) combined Majority Referencing with Procedural Legitimacy, linking formal correctness with participatory validation. Emotional strains that followed were frequently mitigated through emotional de-escalation by temporal distancing (P6), grounded in Emotional De-Escalation codes that followed tense exchanges marked by ambivalence. When normative pressure threatened cohesion, leaders employed reintegration through empathy and personal appreciation (P7), supported by the Reintegration through Empathy codes, which restored relational stability after conflict. Finally, leadership communication repeatedly turned to re-centering collective identity through shared goals (P8), derived from Shared Goal Emphasis and Future Orientation. These moments of forward-looking identity work redirected attention beyond immediate disputes and sustained the voluntary commitment of the group.

Taken together, the eight propositions delineate a layered architecture of leadership communication in voluntary political organisations. Authority was not exercised through singular mechanisms but emerged from the interplay of procedural framing, normative sanctioning, and collective delegation. These dynamics were continuously stabilised through affective regulation, in which ambivalence, de-escalation, and reintegration worked in tandem to prevent fragmentation. At the same time, legitimacy was anchored in dual sources – formal rules and collective validation – while tensions were recurrently resolved by re-centering collective identity around shared goals. This multi-dimensional constellation reveals leadership as an ongoing negotiation of authority, legitimacy, and cohesion under conditions of limited formal hierarchy and heightened relational vulnerability. The framework thereby demonstrates how communicative practices function as the connective tissue that enables voluntary organisations to manage conflict, sustain commitment, and reproduce authority in the absence of coercive enforcement.

Discussion

The development and application of the codebook presented in this study contribute to the systematic analysis of leadership communication within volunteer-based organisational settings. By integrating structured content analysis (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2024) with reconstructive-hermeneutic interpretation (Bohnsack, 2014), the framework offers a transparent pathway from textual segments to higher-order interpretations, articulated through eight interpretive propositions. In contrast to established leadership communication approaches that either emphasise discursive framing without a replicable coding architecture (e.g., Fairhurst and Connaughton, 2014) or privilege broad trait- or style-based models (e.g., Yukl, 2013) the distinct contribution here is a theory-informed, auditable codebook that (a) spans procedural, affective, and identity-related dimensions, (b) preserves communicative multifunctionality via double coding, and (c) explicitly maps subcodes to propositions and, in turn, to higher-order conceptual domains. This design allows researchers to move beyond illustrative discourse analysis towards systematic, comparable analyses suited to the fragile authority structures typical of voluntary and grassroots organisations (see also Della Porta, 2020).

A key strength of the framework lies in its multidimensional perspective: it captures not only the cognitive and procedural dimensions of leadership communication (Fairhurst & Connaughton, 2014; Yukl, 2013) but also the affective and relational dynamics emphasised in political and organisational psychology (Goleman, 2006; Marcus et al., 2008). This comes into view through patterned co-occurrences that underpin the propositions. Authority was repeatedly constructed through Procedural Framing and Procedural Legitimacy, grounding Proposition 1 (Authority Construction through Procedural Framing); at moments of contestation this was reinforced by Normative Pressure (Implicit Threats) and Role–Resignation Coupling, which together substantiate Proposition 2 (Normative Pressure via Implicit Threats). Delegation of responsibility also emerged as a distinct mechanism: Majority Referencing frequently displaced accountability onto collective decisions, anchoring Proposition 3 (Delegation of Accountability to the Group) and illustrating how legitimacy was externalised to the group as a whole. The frequent pairing of Emotional Ambivalence with subsequent Emotional De-Escalation supports Propositions 4 and 6, indicating a recognisable move from cognitive dissonance to temporal calming. After episodes marked by pressure or procedural contention, Reintegration through Empathy became salient, grounding Proposition 7, while Shared Goal Emphasis and Future Orientation anchored Proposition 8 as a recurrent repair mechanism. These linkages demonstrate that the codebook is not merely classificatory; it yields analytically stable propositions that reconstruct how authority, legitimacy, emotion, and cohesion are negotiated in situ.

The Results also highlight communicative tensions between authority-centred and cohesion-oriented leadership orientations, showing how volunteer-based organisations must balance procedural control with relational integration. Appeals to majority support and references to rule-conformity often travelled together, indicating a dual reliance on norms and numbers for legitimation (Propositions 1 and 5). Where these resources proved insufficient, actors mobilised affective reassurance and identity-work (Propositions 6–8). These insights extend broader discussions of organisational resilience, trust-building, and conflict dynamics in participatory contexts (Clarke et al., 2006; Glasl, 2013; Tajfel & Turner, 1979) by specifying the communicative sequences through which stability is restored. They also align with recent accounts of stressors in voluntary organisations, including membership retention and legitimacy pressures, and show how micro-level communicative practices contribute to democratic resilience (Della Porta, 2020).

Methodologically, the contribution is twofold. First, the interpretivist–constructivist stance is operationalised through a dual procedure: structured coding provides reliability and auditability, while hermeneutic reconstruction surfaces latent meanings, role tensions, and institutional narratives (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018). Second, the explicit mapping from subcodes to propositions strengthens interpretive transparency and supports cumulative theorising across studies (Bazeley, 2021; Miles et al., 2020; Saldaña, 2021). Double coding is not a mere procedural safeguard but a conceptual device for capturing communicative multifunctionality – precisely the simultaneity of procedural, affective, and identity work that characterises volunteer politics (Coulston et al., 2025).

Nonetheless, several limitations warrant acknowledgement. The codebook was developed from two critical incidents within a specific organisational setting; while analytically rich for method demonstration, this scope limits claims to representativeness across organisational cultures. The exclusive focus on written communication foregrounds explicit, recordable acts and may under-represent paralinguistic and interactional cues – gaze, prosody, repair – that are central to leadership processes (Goffman, 1959; Wodak, 2009). Stylistic conventions of written intra-party communication (formality, legalistic tone) may amplify the salience of procedural legitimacy and understate spontaneous affect. Researcher embeddedness, while reflexively managed, introduces role-related sensitivities that may shape access and interpretation. Future work should therefore triangulate sources (e.g., meetings, chat transcripts, interviews), incorporate multimodal analysis, and test the framework across different governance logics (consensus-oriented collectives vs. more hierarchical non-governmental organizations (NGOs)) and cultural contexts. Applying formal intercoder statistics on larger datasets will further probe reliability; comparative and longitudinal designs can assess stability and change in proposition patterns over time.

Despite these constraints, the codebook offers a replicable, theory-informed tool for qualitative research into leadership communication, group dynamics, and organisational conflict in volunteer-based and participatory settings. For applied use, the framework can be adapted in a staged manner without losing its core logic. Practitioners can begin with a scoping pass over a small corpus of texts to localise idioms and procedural markers; hold a calibration workshop to tailor definitions and add context-specific subcodes (e.g., informal leadership emergence, issue-based mobilisation frames, digital platform affordances); and then implement iterative coding with memo-based reflection to surface organisation-specific propositions. In NGOs with strong formalisation, Legitimacy and Role/Power clusters may require finer distinctions (e.g., chain-of-command vs. participatory mandates); in activist networks with fluid boundaries, Identity and Cohesion clusters may be extended to include mobilisation calls and boundary-work around in-/out-groups. For student associations or community groups, the Emotion Regulation cluster can be expanded to capture humour, irony, and peer-norm signalling typical of youth or peer cultures. In all cases, short feedback cycles – presenting proposition-level insights back to teams – can support reflective practice, conflict de-escalation, and governance fine-tuning.

Finally, this study demonstrates how qualitative coding, when rigorously grounded in theory and applied systematically, can serve as a conceptual bridge between empirical data and broader theoretical insights into communication, leadership, and group cohesion within democratic, participatory organisations. The codebook is intended as a boundary object for research–practice dialogue: sufficiently structured to be replicable, sufficiently flexible to be adapted, and sufficiently transparent – through its proposition mapping – to enable cumulative learning across cases.

Conclusion

This study developed and applied a systematically designed codebook to analyse leadership communication in a volunteer-based political organisation. By integrating structured content analysis with hermeneutic reconstruction, the analysis generated eight interpretive propositions that illuminate how authority, legitimacy, emotion, and cohesion are communicatively negotiated under conditions of strain. Taken together, these propositions highlight the communicative tensions between procedural control and relational integration that characterise leadership in participatory settings. The main contribution lies in advancing a replicable, theory-informed framework that extends beyond trait- or style-based leadership models by integrating procedural, affective, and identity-related dimensions in an auditable form. Methodologically, the study demonstrates how qualitative coding can serve as a hinge between empirical material and the development of mid-range propositions, thereby supporting cumulative theorising in leadership communication research. The framework also has practical relevance: its modular structure makes it adaptable to a wide range of civic and participatory contexts, from NGOs to student initiatives and activist networks. While the study is limited to written communication in a single case, it provides a foundation for future research that can test and refine the codebook across organisational cultures, governance logics, and modes of communication. In conclusion, the study contributes both a methodological instrument and an interpretive vocabulary for understanding leadership communication in volunteer-driven organisations. By showing how fragile authority and cohesion are maintained through communicative labour, it underscores the value of rigorous qualitative analysis for explaining the resilience of democratic, participatory organisations.

Marcel Patalon, South Westphalia University of Applied Sciences, FB EET, Lübecker Ring 2, 59494 Soest, Germany. Email: patalon.marcel@fh-swf.de

Alvesson, M. (2003). Methodology for close up studies – struggling with closeness and closure. Higher Education, 46(2), 167–193. CrossRef link

Ansell, C., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2023). Public administration and politics meet turbulence: The search for robust governance responses. Public Administration, 101(1), 3–22. CrossRef link

Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., & Gaillard, E. (2023). A systematic mixed studies review of civic engagement outcomes in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 29(1), 1–26. CrossRef link

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational Leadership. Psychology Press. CrossRef link

Bazeley, P. (2021). Qualitative data analysis: Practical strategies (2nd edition). Sage.

Bohnsack, R. (2014). Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung: Einführung in qualitative Methoden (9., überarb. und erw. Aufl.). UTB: Vol. 8242. Budrich. CrossRef link

British Sociological Association. (2017). Statement of Ethical Practice. https://www.britsoc.co.uk/media/24310/bsa_statement_of_ethical_practice.pdf

Chavez, C. (2015). Conceptualizing from the Inside: Advantages, Complications, and Demands on Insider Positionality. The Qualitative Report. CrossRef link

Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591–621. CrossRef link

Clarke, S., Hoggett, P., & Thompson, S. (2006). Emotion, Politics and Society (1st ed. 2006). Palgrave Macmillan UK; Imprint: Palgrave Macmillan. CrossRef link

Coulston, F., Lynch, F., & Vears, D. F. (2025). Collaborative coding in inductive content analysis: Why, when, and how to do it. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 34(3), e70030. CrossRef link

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2025). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (Fifth edition). Sage.

Crevani, L., Lindgren, M., & Packendorff, J. (2010). Leadership, not leaders: On the study of leadership as practices and interactions. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 26(1), 77–86. CrossRef link

Croissant, A., & Lott, L. (2025). Democratic Resilience in the Twenty-First Century: Search for an Analytical Framework and Explorative Analysis. Political Studies, Article 00323217251345779. CrossRef link

Della Porta, D. (2020). How social movements can save democracy: Democratic innovations from below. Polity.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (Fifth edition). Sage.

Dwyer, S. C., & Buckle, J. L. (2009). The Space Between: On Being an Insider-Outsider in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 54–63. CrossRef link

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532. CrossRef link

European Commission. (2018). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj

Fairhurst, G. T., & Connaughton, S. L. (2014). Leadership: A communicative perspective. Leadership, 10(1), 7–35. CrossRef link

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. CrossRef link

Forsyth, D. R. (2019). Group dynamics (Seventh edition). Cengage.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (11th printing). Aldine.

Glasl, F. (2013). Konfliktmanagement: Ein Handbuch für Führungskräfte, Beraterinnen und Berater (11., aktualisierte Aufl.). Haupt Verlag; Verlag Freies Geistesleben.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor books. Doubleday.

Goleman, D. (2006). Working with emotional intelligence (Bantam trade paperback reissue ed.). Bantam Books.

Hansen, N. W., & Hau, M. F. (2024). Between Settlement and Mobilization: Political Logics of Intra-Organizational Union Communication on Social Media. Work, Employment and Society, 38(2), 299–317. CrossRef link

Hellawell, D. (2006). Inside–out: analysis of the insider–outsider concept as a heuristic device to develop reflexivity in students doing qualitative research. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(4), 483–494. CrossRef link

Holloway, J., & Manwaring, R. (2023). How well does ‘resilience’ apply to democracy? A systematic review. Contemporary Politics, 29(1), 68–92. CrossRef link

Jasper, J. M. (1998). The Emotions of Protest: Affective and Reactive Emotions In and Around Social Movements. Sociological Forum, 13(3), 397–424. CrossRef link

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations (2. ed.). Wiley. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/description/wiley033/77018764.html

Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (Third edition). Sage.

Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2024). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Umsetzung mit Software und künstlicher Intelligenz (6., überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage). Grundlagentexte Methoden. Beltz Juventa.

Liu, Y., Zou, G., & Xu, J. (2025). Building resilience of urban governance at the grassroot level: The role and preference of community governors in navigating social crises in China. Journal of Urban Affairs, 1–19. CrossRef link

Mahbub, T. (2017). Case Study 2. In H. Kidwai, R. Iyengar, M. A. Witenstein, E. J. Byker, & R. Setty (Eds.), Participatory Action Research and Educational Development (pp. 235–246). Springer International Publishing. CrossRef link

Marcus, G. E., Neuman, W. R., & MacKuen, M. (2008). Affective intelligence and political judgment [Nachdr.]. Political science. Univ. of Chicago Press.

Mason, M. (2010). Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.3.1428

Mercer, J. (2007). The challenges of insider research in educational institutions: wielding a double‐edged sword and resolving delicate dilemmas. Oxford Review of Education, 33(1), 1–17. CrossRef link

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2020). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (Fourth edition). Sage.

Morrison, C. C., & Greenhaw, L. L. (2018). What skills do volunteer leaders need? A Delphi study. Journal of Leadership Education, 17(4), 54–71. CrossRef link

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, Article 1609406919899220. CrossRef link

Ospina, S. M., Foldy, E. G., Fairhurst, G. T., & Jackson, B. (2020). Collective dimensions of leadership: Connecting theory and method. Human Relations, 73(4), 441–463. CrossRef link

Raelin, J. (2022). What Can Leadership-as-Practice Contribute to OD? Journal of Change Management, 22(1), 26–39. CrossRef link

Riese, J. (2019). What is ‘access’ in the context of qualitative research? Qualitative Research, 19(6), 669–684. CrossRef link

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4e). Sage.

Salmons, J. (2017). Chapter 5: Getting to Yes: Informed Consent in Qualitative Social Media Research. In K. Woodfield (Ed.), Advances in Research Ethics and Integrity. The Ethics of Online Research (Vol. 2, pp. 109–134). Emerald Publishing Limited. CrossRef link

Scarrow, S. E., Webb, P., & Poguntke, T. (Eds.). (2017). Organizing political parties: Representation, participation, and power. Oxford University Press. CrossRef link

Small, M. L. (2009). `How many cases do I need?’. Ethnography, 10(1), 5–38. CrossRef link

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571. CrossRef link

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 33–37.

Trent, S. B., Allen, J. A., & Prange, K. A. (2020). Communicating our way to engaged volunteers: A mediated process model of volunteer communication, engagement, and commitment. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(7), 2174–2190. CrossRef link

Tripp, D. (2011). Critical Incidents in Teaching (Classic Edition). Routledge. CrossRef link

University of Oxford. (2022). Research Ethics Policy (Version 3.0). Central University Research Ethics Committee (CUREC).

Vestergren, S., Drury, J., & Hammar Chiriac, E. (2019). How participation in collective action changes relationships, behaviours, and beliefs: An interview study of the role of inter- and intragroup processes. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 7(1), 76–99. CrossRef link

Wodak, R. (2009). The discourse of politics in action: Politics as usual. Palgrave Macmillan. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/alltitles/docDetail.action?docID=10490572

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (Sixth edition). Sage.

Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organizations (8. ed., global ed.). Always learning. Pearson.