Abstract

This paper interrogates the evolution of struggles over a park in Copenhagen, Denmark. This evolution is situated between local residents’ efforts to obtain socio-environmental justice, and attempts to manage the space by municipal authorities for different agendas. Analytically bringing the concepts of environmental justice and urban managerialism into focus and drawing from lessons and stories of the past, we show how managerial practices and justice struggles evolve iteratively over time. We document how the beginnings of Folkets Park (the People’s Park) in the late 1970s were characterized by struggles over distributional justice between economically marginalized residents and urban managers. The conflicts changed to contestation over procedural and interactive justice, due to the formalization of the park and expanding struggles for recognition and claims to the space by a diversifying population. Trends of decentralization to municipal levels and greater inclusivity have also taken root, maintaining urban managers as distributors of justice. Yet, we demonstrate that urban managers do not act in isolation. Local activists are an important force in urban development, producing an iterative evolution of strategies of management and justice struggles in this neighbourhood. Urban managerialism in Copenhagen, including the more contemporary efforts at inclusion, is also (re)shaped, inhibited, and co-opted by the larger context of increasingly neoliberal and socially divisive political agendas. By examining this micro-cosmos of a contested urban park, we show that urban planning and development is an inherently political and contested practice, and argue for urban managers to continuously seek inspiration from local activism in the pursuit of just cities of today and tomorrow.

Introduction

At the heart of one of the most diverse neighbourhoods of central Copenhagen, Nørrebro, lies a green park called ‘Folkets Park’ (the People’s Park). Under a half-hectare, this small park has a rich but conflicted past and present, and has long been a symbol of local activists’ efforts for self-determination against top-down, technocratic efforts of social control through urban planning. Folkets Park emerged out of a dense area targeted in the 1970s for one of the first contemporary attempts at urban renewal in Copenhagen. The area’s low-income population was also characterized by a reputation for social solidarity and grassroots activism, and in this context, renewal efforts sparked a tumultuous period in the history of municipal/resident relations (Schmidt, 2017).

A walk through the park today reveals a diversity of daily users, including (but not limited to) coffee-sipping young parents pushing costly prams, black-clad folks associated with anti-capitalist movements, homeless African migrants warming by a fire pit, and smoking male youth of primarily Middle Eastern descent, often presumed to be gang-affiliated. This very mix provoked renovations by the municipality in recent years, efforts that resonate with a citywide attempt by urban managers to create spaces that welcome all types of people. The latest renovation (2012-2014) was largely deemed a success – even by some of the toughest local critics. However, the park today is arguably more troubled than ever. It was recently at the centre of a gang war and a site of violence and vandalism perpetrated against arguably the most vulnerable users: the homeless. At the same time, the neighbourhood’s housing prices are rapidly rising – even as its diversity has come to be celebrated.

This raises questions over what justice in this park can look like, in this context of a culturally, ethnically, and socio-economically diverse population, and against the background of a western society undergoing neoliberalism and an increasingly divisive, xenophobic politics. Specifically it raises questions around the motivations and practices of ‘urban managers’ (city officials and increasingly private actors), the implications of their actions, and how both grassroots activism and larger trends interact with and (re)shape these actions. We also wonder, what can the history of a place teach us in relation to just urban futures? This paper takes an environmental justice perspective and engages with the concept of urban managerialism. Environmental justice calls for an examination of difference in relation to social groups’ experiences with environmental phenomena, including urban green spaces. ‘Urban managerialism’, following Ray Pahl’s provocative 1970 book ‘Whose City?’, calls for sociological attention to urban managers as critical to producing just urban spaces. We also attend to the largely omitted significance of local activism, to deepen the analytical power of urban managerialism.

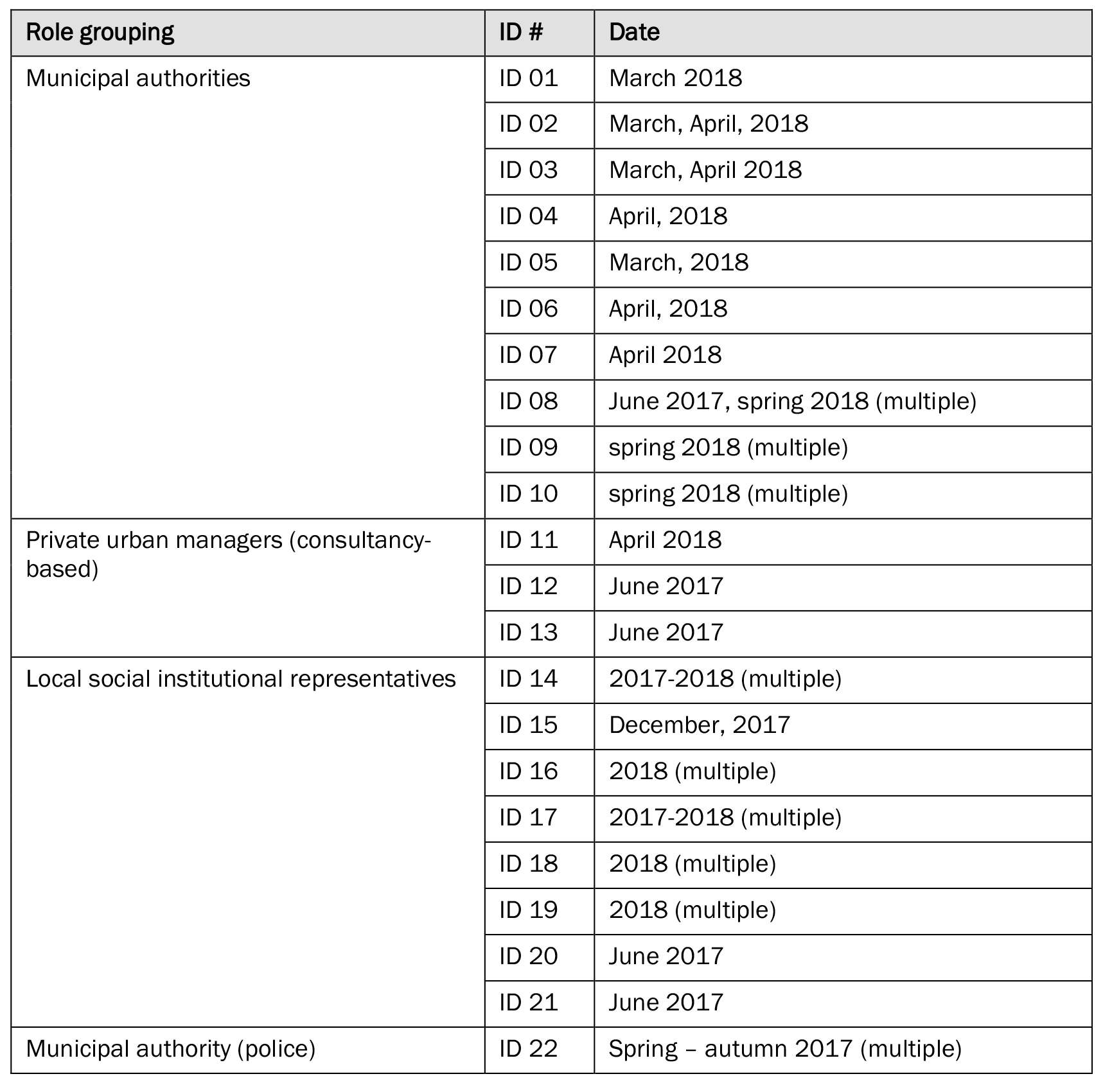

What is a park, if not a piece of the city? This leads us to ask, whose park? To respond, we draw inspiration from Pahl’s maxim to “always begin with history” in critical urban research (Crow and Takeda, 2011: 3). Specifically, we undertook ethnographic research over the past five years in the City of Copenhagen. This includes twenty-two formal and numerous (>100) informal conversations with public officials from neighbourhood to municipal levels, architects and consultants engaged in renewing Folkets Park, squatters from decades past, current and former political activists and politicians, representatives of area homeless shelters, police officers, and of course, park users. Formal interviews occurred during 2017-2018. Both authors reside/resided in the neighbourhood and are/were park users themselves. Since 2016 and continuing today, the first author has engaged with the park and its users through educational and voluntary activities, for instance by leading university lectures on environmental justice using Folkets Park as a case, and through volunteering in social organizations. Our research also draws from documents containing personal accounts of past and current events, archival planning documents, news items, and academic research on related issues. Most referenced and quoted text contain the authors’ own translations to English from Danish.

Shedding light on four decades of struggle over a park in Copenhagen, this article aims to inform and inspire urban manager practitioners in Scandinavia and beyond as well as environmental justice researchers. Below, we unfold a historical account of the park and neighbourhood. But first, we introduce urban managerialism and environmental justice as useful analytical lenses for examining the park’s history and for grasping the rationales of various actors and the implications of the park’s legacy.

Urban Managerialism

In his seminal 1970 book Whose City?, Ray Pahl encouraged urban sociologists to focus on ‘urban managerialism’ from a humanist perspective, which positions city officials as mediators and gatekeepers to the urban experience. Pahl wrote in a context in which large-scale public institutions still dominated access to scarce urban resources. His observations of conflicts over urban resources from the mid-1960s to 1970s were written on the cusp of London’s transition from a Fordist-Keynesian to a global neoliberal city (Burrows et al., 2017; Mayer, 2017). Pahl (1970) argued that public urban managers were critical in determining opportunities and quality of life for residents, through e.g. access to housing and education, thereby producing territorial inequalities and social exclusions.

With the emergence of Marxist perspectives on cities under capitalism and neoliberal urban transformations especially since the 1970s (Harvey, 1989), urban managers came to lose their perceived importance as bearers of distributive justice, “within overarching structures of exploitation and inequality” (Forrest and Wissink, 2017:155). Pahl’s later work reflected on these developments. While also calling for attention to “the constraints placed on urban managers themselves by the capitalist mode of production”, he renewed his appeal to researchers to interrogate public officers, following a belief that they could still help ameliorate unjust societies (ibid.:157; Pahl, 1975). Other scholars have also pointed out how “the urban managerialism agenda” remains “more relevant than ever” (Forrest and Wissink, 2017: 163). For instance, Dooling’s (2009) work on the harms of ecological gentrification to the homeless in Seattle’s urban green spaces, points to policymakers and administrators but also “front-line workers” in city government and service agencies. Dooling (2009: 625) describes how “street-level bureaucrats”, i.e. “case managers, shelter staff, law enforcement officials and government representatives”, directly affect the lives of homeless people: “they can grant or deny access to a shelter; they can choose when to incarcerate individuals for violating anti-camping ordinances. Each encounter is an instance of policy delivery where government officials, social service workers and law-enforcement personnel function with discretionary power, making decisions about when to apply, or suspend, institutional rules and juridical regulations. Each encounter is an intimate experience of sovereign power, and the decisions made have immediate and bodily impacts (…)”. Mayer (2017: 176) adds that under current neoliberal urban transformations, urban managers are expanding beyond the traditional public sector, to include “additional and distant” actors such as “unelected technocrats, especially financial technocrats, as well as global investors and developers”. An important implication of this trend is weakened accountability.

Pahl’s work on urban managerialism can be deepened by bringing in the generally absent perspective of urban social movements and local activism (Mayer, 2017). This is important to more fully understand struggles over urban spaces, particularly following neoliberal restructuring in many cities since the 1960s (ibid.). In the neoliberal city, urban spaces and services are increasingly privatized. Economic growth takes precedence, producing a context ripe for worsened social polarization and pushback from resident activists who lose out under ‘market’ governance. Recognizing opposition helps analyse how activists (re)shape cities, as well as the constraints urban managers face when seeking to strike a balance between the needs of especially vulnerable residents and growth-oriented development. In other words, we need to focus “not only on city managers and their bosses, but also on their challengers” (Mayer, 2017: 169). Considering this, we analyse the actions of both urban managers and activists over time in their struggles for environmental justice in Folkets Park and its environs. While ‘activists’ are heterogeneous, we use the term ‘local activists’ to signify those who reside and/or spend substantial time in the neighbourhood and who engage in conflict with authorities and other powerful groups under the broad banner of social justice. We also expand the urban managerialism perspective by bringing ‘green’ resources in focus. Urban green spaces are especially relevant for contemporary urban planning agendas, which position them as critical for liveability as well as ‘solutions’ to sustainability dilemmas (European Commission, 2018). Yet as we lay out in the next section, they are also critical spaces where social/environmental injustices can unfold over time.

Environmental justice in relation to urban green spaces

Environmental justice as a field of inquiry is concerned with the “intertwining of environment and social difference”, or how different social groups have very different experiences with environmental phenomena (Walker, 2012: 1). Originating from the overlapping interests of the civil rights and environmentalist movements of the US especially through the 1960s-1970s, environmental justice is now a rallying cry for social movements and an important conceptual lens for research. Substantial scholarship on justice in urban green spaces has emerged especially over the past decade, due to the important benefits green spaces provide to urban residents and the reality that such amenities are rarely enjoyed equally (ibid.). However, a justice perspective on urban green space research, planning, and management in European cities remains limited (Rutt and Gulsrud, 2016).

Justice considerations invoke philosophical and situated debates, acknowledging that justice claims can be multiple and conflictual, and that elite interests often dominate. The nature of distribution, procedures, and recognition are central to environmental justice struggles (Schlosberg, 2007). In relation to urban green amenities, the distribution debate provokes critical inquiry into the allocation of green spaces in relation to demographics. Such inquiries often follow assumptions that green spaces are desirable ‘environmental goods’ that provide benefits to urban dwellers (Rutt and Gulsrud, 2016). Distribution inquiries may also examine difference in resource allocation to create and/or maintain green spaces. Yet, justice scholars will quickly challenge assumptions of urban green spaces as unequivocally good. ‘Good’ green spaces can also produce ‘bad’ (exclusionary) outcomes, such as those that cater to only certain segments of the population (Walker, 2012), or as evident in processes of ecological gentrification (Anguelovski, 2015; Dooling, 2009). Meanwhile, procedural justice interrogates who is included and excluded in decision-making processes (Schlosberg, 2007). Such an inquiry will also examine the quality of participation, asking whether and how the inputs from marginalized people are reflected in policies and physical landscapes.

The concept and practice of recognition addresses the ‘why’ of distributive and procedural realities. A ‘politics of recognition’ invokes situated struggles, calling attention to identity-based exclusions and institutionalized systems of oppression (Sikor et al., 2014). As such, a focus on recognition in struggles for justice may redress the “historical amnesia and methodological presentism”, or the scholarly and societal tendency to understand social phenomena within a limited contemporary framework, thereby obscuring the political nature of public narratives at a given point in time (Schmidt, 2017: 43). This echoes Pahl’s ambitions for historically informed sociological analyses. As an instrument of justice, recognition demands the acknowledgement of typically excluded social groups (e.g. migrants, women of colour, the elderly) and their meaningful inclusion in political spaces (Fraser, 2009). ‘Interactional justice’ is a related, though more narrow notion. It calls for sensitivity to how different types of people are – or importantly, expect to be – treated (Low, 2013). Interactional justice focuses on the quality of interpersonal encounters, oriented toward the absence of physical, verbal, and psychological violence (Low and Iversen, 2016). Like the other aspects of environmental justice, this perspective raises practical and justice implications, in relation to actual use as well as fairness around access and enjoyment, of public goods and services like green parks.

Neighbourhood roots

Folkets Park in Nørrebro became a physical reality in the mid-1970s but its roots extend farther back, to an area that developed rapidly and haphazardly. Nørrebro was established as a neighbourhood of Copenhagen in the mid-19th century. It was quickly characterized by a working class population seeking relief from the densifying urban core, the result of migrants pursuing employment during the height of industrialization (Dansk Byplanlaboratorium, 1996; Københavns Kommune, 1996). Activism also became a defining feature, as Nørrebro grew into a hub for the national workers’ movement (Schmidt, 2015, 2017).

Yet, Nørrebro residents increasingly suffered from severe socio-economic and spatial challenges emerging from the burgeoning population. Unregulated housing in backyards and corridors brought a dense, dark appearance. Most habitants occupied two-room apartments, many lacking toilets and hot water (Dyck-Madsen, 2004). Still, a rich community culture flourished including diverse social movements. By the 1960s, neighbourhood activists focused heavily on safe, affordable housing for all. Known as the ‘Slum Stormers’ (later the ‘BZ’ers, a shortened label from the Danish word for ‘occupied’, i.e. ‘besæt’), the movement famously squatted buildings across the city and particularly in Nørrebro (Københavns Kommune, 1996; Øvig Knudsen, 2016).

Urban renewal sparked violent neighbourhood battles

City authorities were well aware of the dilemmas in Nørrebro and designated it as one of the first areas for ‘renewal’, setting in motion a sweeping demolition and reconstruction agenda from the early 1970s (Københavns Kommune, 1996). This included new ‘social housing’ (Larsen and Hansen, 2008), developed by private firms with public financial support and regulation to ensure accessibility for marginalized groups (Vestergaard, 2016). In 1977, a new comprehensive plan was developed for the entire city (Københavns Kommune, 1979). In the plan, controversial Mayor Egon Weidekamp (in office 1976-1989), backed by public and private partners, called for special attention in the ‘Black Square’ – a derogatory name for the vicinity of present day Folkets Park (Dansk Byplanlaboratorium, 1996). The plan was adopted in 1979 with apparent approval from the resident council (ibid).

While heavily top-down in practice, Denmark like other countries in this era was experimenting with local representation in urban planning through the formation of resident councils (beboerdemokrati) (Agger and Hoffman, 2008; Dansk Byplanlaboratorium, 1996). The Municipal Planning Act of 1977 and further legislation in 1982 decentralizing planning from the State to the municipal level enabled Wiedekamp to more easily impart his vision on the city as a whole and Nørrebro in particular (Dansk Byplanlaboratorium, 1996).

Despite the ‘representation’, residents had little actual influence and renewal efforts were widely contested (Dansk Byplanlaboratium, 1996). Many called for the refurbishment of existing architecture rather than demolition and resistance took the form of squatting, barricading of buildings, and violent encounters with police. The conflicts led Mayor Weidekamp to describe Nørrebro as a warzone, characterising public authorities’ antagonistic relationship to the area (Dansk Byplanlaboratorium, 1996). Yet in spite of conflicts, an unanticipated side effect arose as residents experienced open spaces for the first time. Frustrated by the lack of children’s play areas, local activists established a playground, ‘Byggeren’ (The Builder), on a cleared lot across the street from what would become Folkets Park. The playground, “a much needed sanctuary” for the neigbourhood, became so popular that it even received temporary status as a municipal institution (Dyck-Madsen, 2004: 5).

Arguably the most dramatic conflict of the period was the ‘Battle for Byggeren’, a battle epitomizing struggles for distributional environmental justice. After years of delays, the city and private development interests prepared to commence construction. In 1980, Byggeren was demolished under massive police presence to remove resistant local activists including children. Byggeren was re-built; the bulldozers and police returned. Emergency law was declared, and after months of violent conflict, street blockades, and hundreds of arrests, construction commenced. The experience was referred to as the first great popular mobilization since World War II.

Folkets Park is born

While the battle for ‘Byggeren’ was lost, others succeeded – including the fight for Folkets Park. The lot where Folkets Park stands today was also cleared of dilapidated housing in the 1970s to make way for new construction. Like Byggeren, Folkets Park was quickly established by residents cum activists, who laid claim to the space through the reuse of materials from demolitions like cobblestones, planks, and bricks and trees and bushes from local allotments (Folkets Hus, 2004). A squatted building alongside Folkets Park named ‘Folkets Hus’ (the People’s House), which had served as a base to organize resistance to Byggeren demolitions, also provided a meeting place to maintain Folkets Park and organize further political action and community building. Like Byggeren, Folkets Park became a symbol of local activists’ self-determination and demands for distributional justice, against authorities’ vision that “apparently meant that Nørrebro residents could do without greenery” (Folkets Hus, 2004).

Folkets Park thrived for a time. Respondents explained that the peace was at least partly rooted in authorities’ fatigue following the conflict over Byggeren. However, Folkets Park was not yet safe from the ambitions of development-oriented, technocratic planners and companies. By the 1990s, renewed interest by the municipal authorities and private developers threatened to turn Folkets Park over to new construction. This interest stemmed from Copenhagen’s population growth and economic revival from the late 1980s, following 20 years of economic stagnation (Hartvigson, 1993; interviews with Nørrebro park managers and Copenhagen Municipality architect (ID 01-04). The growth of the city was no accident; plans for urban renewal and economic revitalization put forth in 1990 through an alliance of local and national decision-makers established a publicly-owned, privately run corporation (By og Havn, ‘City and Port’) through which to carry out city-wide renewals (Katz and Noring, 2017). The renewal included major waterfront redevelopment, urban renewal, construction of entirely new neighbourhoods, and a new metro system. These amenities aimed to entice suburbanites and capital back to the now sustainability-oriented and investable city (and according to some, are to thank for Copenhagen’s current high ranking amongst the world’s most prosperous cities and on quality of life and liveability indices (Detter and Folster, 2017)). Further decentralized modes of neighbourhood renewal (under names like ‘neighbourhood lift’, ‘area lift’, ‘partnership projects’, and today’s ‘area renewals’ (Områdefornyelserne) were also deployed, as “one of the smallest and at the same time strongest tools in city policy” (Christensen, 2014: 7). These public interventions target “worn urban areas” and aim to link “municipal officials with citizens, associations, institutions, and business and cultural life”, reflected the ongoing shift toward inclusive urban development (ibid.).

Meanwhile, local activists reacted strongly against the proposed plan to ‘develop’ Folkets Park area. Increasing public recognition of residents as legitimate claimants paved the way for the adoption of more formal strategies with a procedural justice orientation, characterizing a shift in how local activists and authorities dealt with one other. Now, activists were organizing petitions and speaking up in public fora, as opposed to the predominantly violent street-based confrontations of the past. Despite broadening recognition of the value of parks – and of the residents’ voices as legitimate – the city council nonetheless approved new building construction. As plans took shape in 1996, local activists responded by forming Folkets Park Initiative. “The idea was to develop an offensive defence for the park, by expanding it with a playground (…), weekly working days – with music, food, entertainment and cozy co-work. And a nature / sculpture playground took shape…” (Folkets Hus, 2004). Through petitions and physical occupation including infrastructure development, resident activists effectively communicated the local resistance to external development interests in their park. By early 1997, the housing firm decided to withdraw. Folkets Park was safe once more.

Yet in late 1997, a final attempt was made to retake Folkets Park for development interests. Municipal bulldozers crept in before sunrise one autumn morning and began to demolish the park infrastructure. They did not get far. Already wary residents awoke and rushed to intervene. After numerous complaints from park defenders, the city (City Renewal – ‘Byfornyelsesselskabet’) eventually allocated compensatory funds for the damaged infrastructure and apologized for their actions, which they called a “mistake” (Folkets Hus, 2004). Nonetheless, authorities also justified their actions based on a bureaucratic condition: that residents lacked an ‘official’ park contact person with whom to discuss plans – effectively ignoring the Folkets Park Initiative representative body (Folkets Hus, 2004). This revealed the continued dominance of technocratic norms in shaping the legitimacy of claims to space, through e.g. arbitrary bureaucratic protocols – something that the shift toward formal processes and appeals to procedural justice may have inadvertently played in to.

From 1997 to 2004, frequent public actions and protests continued to take place over Folkets Park. Even representatives from the police, churches, and Danish environmental organizations came to express their support. In 2004, park defenders finally succeeded in gaining official recognition for Folkets Park as an open, public area, through the passing of a revised ‘Local Plan’ (Københavns Kommune, 2004). After more than thirty years of struggle for both distributional and procedural justice, Folkets Park was now as secure as it could be.

Changing demographics and park renovations

Meanwhile, over the span of a few decades, Nørrebro’s population was shifting with an influx of migrant families from beyond European borders (Københavns Kommune, 2012). Denmark as a nation has and continues to struggle with integration dilemmas and xenophobia (Zucchino, 2016). This demographic trend in Nørrebro was stimulated both by the social housing programmes since the 1980s and because of the neighbourhood’s tradition of solidarity with marginalized segments of society (Larsen and Möller, 2013; Steiger, 2017). Facing difficulties with finding employment and general social exclusion, some ‘migrant’ youth in Nørrebro have, especially since the 2000s, turned to gangs to find an income, identity, and sense of belonging (Pedersen and Lindstad, 2011). Nørrebro also hosts several homeless shelters, welcoming Danish, European, and increasingly, non-European homeless migrants (Project Udenfor, 2012).

Paradoxically, the park that had been established by locals in spite of the municipality now became subject to municipal rules and management. As such, around the time Folkets Park achieved official recognition, city authorities also diagnosed the park as in need of a makeover. They described Folkets Park as “very worn” and “characterized by vandalism” (Københavns Kommune, 2005: 10). The municipal vision for the park renewal was ” a strong, flexible and robust design” but above all else, it had to have “space for all”, including “children, students, homeless people, young people, immigrants, the elderly” (Københavns Kommune, 2005: 4). The municipality led a “novel” participatory process for the park renewal, where proposals from landscape design firms had to be discussed with resident representatives (ID 07)). In the early 2000s narratives encouraging local participation in urban planning and renewal were gaining traction, demonstrating an ostensible evolution towards justice-oriented practices (Agger et al., 2000). A former municipal renovation project manager (ID 07) described the importance of resident dialogue at that time: “That was very important, because there was not a very good relation between the municipality and the citizens in this part of Copenhagen. Because of the renovations in previous decades (…) and all the confrontations between citizens and police. And for many years, until where I got into the picture, the park was driven by locals.” At the same time, there was great difficulty in engaging certain groups, namely “young people”, “Muslim women”, and the homeless. The manager explained, “even though we had many people, they only represented a tiny part of the population”, with most from the older local activist community.

A price tag of nearly 1.7 million euro (12,4 million kroner) for the park renewal stirred up contempt. The new version of the park came to be most (in)famous for a massive metal bridge extending across a portion of the park – at a price tag of approximately 470 thousand euro (3.5 million kroner; Indlændinge-, Integrations- og Boligministeriet, 2016). The bridge was an eyesore for many residents, and worse, it came to represent good intentions gone awry. A park user’s comment epitomized local sentiments: “I both love and hate [the bridge]. A huge walkway made of metal (…), no visible obstacle to climb, and just appears as completely meaningless. (…) I also love it, because it shows how it often goes wrong when different parties have to agree on a structure in a place plagued by past traumas” (Vedel, 2014). Despite the renewal, Folkets Park could not “shake off its bad reputation for gang guys and homeless people” (Koefoed, 2014) with the presence of these two groups only continuing to grow. Many gang members were born and raised in the neighbourhood, while many homeless migrants were drawn to the park by expectations of community and support (Juul, 2017). Thus while the process of user engagement may have been an important step toward stronger procedural justice in Nørrebro, when situated in broader context of societal exclusion, this ‘good’ process appeared to have been thwarted. The high cost combined with the physical outcome – and moreover, the renovation’s failure to bring about substantive change to the area – became a source of provocation for many residents.

Even municipal officials later admitted: “this version (…) never managed to attract more guests despite millions of investment in, among other things, a massive steel bridge. On the contrary, the park gradually became darker and more bare, and at times it was mostly African homeless people and groups of young men who used it. Eventually, there was almost a western-style atmosphere in the park: raw, masculine, wind blown, and empty” (Indlændinge-, Integrations- og Boligministeriet, 2016:38). The presence of African homeless people and ‘young men’ was thus equated with both danger and emptiness, invoking dehumanizing narratives that risk precluding “normal options for interaction and the establishment of relationships” (Schmidt, 2017:49).

These narratives were employed to legitimate another park renewal, particularly following a violent episode at the park in 2012 in which several young men were mistaken for rival gang affiliates and beaten by local gang members (CPH Post, 2012). In response, the City of Copenhagen developed a security plan for Inner Nørrebro with a special focus on Folkets Park. The official story was thus: “Folkets Park needed a second facelift, and the renovation would take place in close collaboration with the residents of the area. Security should be restored through ownership” (Indlændinge-, Integrations- og Boligministeriet, 2016). This effort reflected the growing call for local participation in policies, including on integration, safety and security, the development of urban nature, and in the explicit ‘Sammen om Byen’ (Together for the City) strategy (Agger and Hoffman 2008; Københavns Kommune, 2010, 2011, 2015a,b,c, 2018). Such participation schemes continued to be viewed with suspicion by some local activists who fear such processes may manufacture their consent for legitimizing state-sponsored gentrification of the neighbourhood (ID 14).

The second renewal had a significantly smaller budget of 215 thousand euro (1.6 million kroner). This time the City of Copenhagen hired a private team to carry out the design and facilitate management of stakeholders. The team was led by an expert in working with “cities and people from an artistic platform” (Balfelt, 2018) and involved a local architectural firm. The project aimed to “respect the history and soul of the park”, and more concretely, “to create more activities in the park, facilitate more people using the park, and thereby increase security in the park” (Balfelt, 2016). Once again, the ambition was to engage all users: “the area’s residents, activists, traders, young local men, and homeless people from distant parts of the world” (Koefoed, 2014). But as step one, the team engaged in a “long process” with various city officials to ensure that – despite the participatory rhetoric – the municipality was genuinely committed to including residents in the process. The team “[had to] make it understood, also politically, that what’s going to happen here is not cleaning out the park, and getting rid of disturbing elements, but more working in a different way and seeing how we can be here together” (ID 11).

Not everyone was enthusiastic about another park renewal or engaging in the participatory process, no matter who led it. A representative of the Nørrebro Local Committee (which brings together citizen volunteers and local politicians since 2008) stated in local media, “The most important thing is not to spend money to renovate, but instead spend the money on the vulnerable and thugs in the area” (Tromborg, 2013). Some Folkets Hus affiliates also criticized the endeavour. A spokesperson pointed out that local conflict management mechanisms were already in place and called the renewal unnecessary; another worried that “‘space for all’ usually means space for the white middle class” (Balfelt, 2016). One of the landscape architects also described (ID 12), “This resistance toward the municipality was still alive. (…) It’s part of the Nørrebro feeling: ‘we can do it ourselves, this is the People’s Park. And we don’t need architects either!’”

The renovation team described their approach as one in which outcomes were not predetermined. Rather, they aimed to learn about different park experiences and then use their expertise to create a more inclusive space (ID 11-13). The team held numerous meetings; in total, they claim to have spoken with about 175 people. A ‘surprising’ outcome of their discussions was the ‘many similarities’ in interests across user groups (ID 11), e.g.: “‘The young men with gang relations wanted children to be able to safely play in the park’” – though they also wanted to ‘do their business’ in peace – understood to be the sale of hash (Tholl (2017) interviewing Kenneth Bahlfelt). The consultancy team worked to accommodate everyone with some decisions lauded by all such as the repurposing of the bridge materials toward a vibrant new playground. Other decisions taken by the team, such as installing armless benches designed for those seeking space for sleeping, or the new ‘zoned’ track lighting, were more controversial. The city argued that a fully lit park would create a more secure space, while the team’s interviews with certain users revealed that darkness also provides security for some. The design team eventually secured lighting that kept a central path moderately lit, while leaving some parts of the park in shadows. With the intense engagement of residents, and the diversity of interests considered, a public space was created that certainly seemed more conducive to interactional justice for more users.

This renovation received widespread praise and the initial wary reactions by critics turned to satisfaction with both process and outcome (ID 11-17); also see Balfelt, 2016). One journalist described the process undertaken by the lead consultant: “He prioritized community engagement and broke rules in ways that might leave some urban designers in awe, and others aghast” (Tholl, 2017). Clearly, the 2014 renewal of the park was one of the most radical experiences of participation in the area. During the preceding 30+ years, residents seemed to have mattered little – in fact were downright burdensome – to decision-makers when it came to Folkets Park. But would inclusion be enough to change the social (and economic) challenges facing the area? Was it instrumentalised for other ends? Now we turn to Folkets Park today in an effort to understand the outcomes and implications of park renewals.

Folkets Park and environs today

Nørrebro retains a strong identity with close links to the past. But as we have shown, it has undergone substantial spatial and social changes. The ‘renewal’ of the 1970s-1980s did establish large courtyards within many apartment blocks and overall, the neighbourhood is visibly more open and green, as even a quick comparison between photo archives (e.g. Nørrebro Lokalhistoriske Forening og Arkiv, 2018) and Google Maps reveals.

Nørrebro is often described as one of the most ‘ethnically’ and ‘culturally’ diverse areas in the city. The official tourism website Visit Copenhagen labels Nørrebro ‘colorful’ and ‘multicultural’, whereas other central neighbourhoods receive titles of ‘posh’, ‘family-friendly’, and ‘hipster’ (Visit Copenhagen, 2017). In recent years, Nørrebro has seen an explosion of shops, bars, and cafes, leading international press like Vogue magazine to describe it as home to “the Coolest Spots in Copenhagen” (Lewis, 2016). These changes have taken place in part through the strategic commodification of diversity, which enrols such ethnically diverse neighbourhoods into tourism development agendas (Schmidt, 2017). The changes have been accompanied by steeply rising housing prices, strongly suggesting gentrification (Hansen and Karpantschof, 2016; interviews with Nørrebro park managers (ID 03,04) and Nørrebro Local Council representative (ID 05)).

Despite unfolding gentrification, Nørrebro retains a high share of public housing compared to other neighbourhoods (ID 05,06). The neighbourhood also continues to have comparatively higher rates of crime, lower rates of education and employment and is among the six areas referred to in the city’s Policy for Disadvantaged Areas of Copenhagen (Københavns Kommune, 2012). One of Denmark’s most notorious gangs, Loyal To Familia, stems from the heart of Nørrebro (Toft, 2017) and members have a strong presence at Folkets Park. Since 2014, inner Nørrebro, including Folkets Park, has received public funding through an ‘area renewal’ initiative (until 2019), the contents of which spell out the now familiar vision to “create a greener neighbourhood with space for everyone” (Områdefornyelsen Nørrebro, 2014: 3).

When we started writing this article in 2017, a gang war was underway in Nørrebro, with approximately 30 shootings throughout the area including next to Folkets Park (Ingvorsen, 2017). In the spring of 2017, roughly 30 bags of homeless people’s belongings, stored for months under tarps in a corner of Folkets Park, were set on fire. Some of the African homeless were also beaten and/or verbally threatened. There was little dispute amongst local institutions including the police, Folkets Hus, and homeless shelter representatives that the vandalism and aggression was instigated by gang members reasserting their claim over the park – at least in relation to homeless migrants. As Schmidt (2015: 60) observed, Nørrebro has a long tradition of diversity and conflict, but not necessarily in ways that undermine identification with the neighbourhood. Here, gang members too are residents with attachments to and visions for their public spaces, which homeless migrants may disrupt. Such actions also disrupted the good intentions planners had for creating safe, inclusive spaces.

There has also been a push toward stricter enforcement of anti-camping rules in recent years (ID 18, 19, 22; also see Hecklen, 2017; Sheikh, 2015; Politiken, 2014). The Mayor of Copenhagen, Frank Jensen, defended this push with this vivid description: “We know from experience that when such areas are used to make camp, many problems follow. We know that the homeless often leave waste, human feces and used toilet paper. (…) It’s disgusting” (Sheikh, 2015). Here Mayor Jensen depicts homeless as dirty, something that disrupts the branding of Copenhagen as a liveable, green, and healthy city (also see Rose, 2017). Paradoxically, many end up on the street precisely because of the lack of shelters and other public services. Such negative attitudes towards homeless are also reflected in laws like that passed in 2017 for “Sharpening of the Penalty for Extraterrestrial Begging” (Justitsministeren, 2017). The law states, “[the] government wishes to target foreign travellers who camp in public places, for example in parks and on public roads, and which (…) create insecurity (…) for both residents and passers-by (…)” (ibid). With this law police no longer need to give a warning before fining or imprisoning those considered to be ‘creating insecurity’ through, e.g., begging, camping, or bottle collection – a widespread activity to obtain recycling refunds in lieu of legal, paid work.

Mayor Jensen’s revival of the 1970s-esque narratives of unsanitary conditions in Nørrebro to ‘cleanse’ the public of homeless may legitimate the actions of some residents in ‘doing their part’, whether through violent methods or simply formal complaints. A police officer (ID 22) with a decade of experience in the neighbourhood described, “We were told to enforce anti-camping rules. The signal came from the Mayor. (…) Since the renovation, the homeless people became more a thorn in the eye, for some people. They complain.” As Juul (2017) explained, there is an ongoing exploration of the limits of tolerance in Nørrebro, where ‘conditional hospitality’ is produced by the public portrayal of migrants as a threat to society. A nearby shelter employee (ID-19) reflected, “If it’s a group that seems to be in the same social class as you, you’d go and talk to them, say ‘dude, cut it out’. But because they are homeless, it’s ‘Hey! They shouldn’t be here, they should respect me’. It’s not so simple, but people often feel entitled to tell people of lower classes what they should do, and how to do it.” These laws come despite municipal claims of creating spaces for all as well as increased security through the inclusion of diverse users (Københavns Kommune, 2015e; interview with Copenhagen Municipal architect (ID 01)). Considering the amenities installed during renovation aimed at servicing the homeless (e.g. armless benches), the same shelter representative pointed out, “If they sleep in groups [a safety mechanism prohibited in the anti-camping rule], the police are gonna wake them up. (…) I think it’s hard to say the place is gonna benefit [the homeless], when the government says, ‘By the way, you’re not allowed there.” The Mayor’s public statement simultaneously spells out to residents what the threat to the Copenhagen brand is and how it should be dealt with. The passing of such an anti-camping and anti-begging law targeting foreigners reminds urban dwellers of precisely who, and who does not, belong in Copenhagen. Meanwhile the response of some resident groups also begs the question: do homeless people only belong in worn and degraded spaces?

A year after the fire was set to homeless’ belongs (spring 2018), the foreign migrants have returned to the area, albeit cautiously. One of the African homeless migrants explained that they no longer keep items of value in the park: “Just small small things. Nothing important.” A homeless shelter employee described how despite the uneasiness and tension, the park still serves as a valuable base for the homeless: “It’s a perfect location for shelter, work, food, and socializing. They don’t feel they stick out that much. Imagine, they’d never hang out in Frederiksberg [a neighbouring municipality]. And I guess they wouldn’t be so welcome there.”

Whose park?

In taking seriously Pahl’s maxim to ‘always begin with history’, we have strived to excavate the ways in which changing policy, urban management practices, and reactions from local activists have contributed to four decades of struggle over Folkets Park. We set out to understand the practices of urban managers and the implications of their actions, how both grassroots activism and larger trends interact with and (re)shape these actions, and what history can teach in relation to just urban futures. Drawing from both environmental justice and urban managerialism, we bring green amenities into focus as an important contemporary urban feature, and show how the justice dilemmas they represent have changed over time, alongside Copenhagen’s managerial model. Analysing the perspective and role of activists enables us to see beyond the ways in which ‘traditional’, or even increasingly private, urban managers allocate resources, and consider how a broader range of actors negotiate control of valued resources over time. Our analysis also critically considers the motivations of urban managers, specifically their conceptualizations of ‘space for all’, which we discuss further below.

We have presented a case that shows an evolving model of urban managerialism and development in the City of Copenhagen. We witness the increasing inclusion of local residents and diverse groups (mirroring global trends, Aitken, 2012), and a trend toward deconcentrated power to the municipal level. Following neoliberal tendencies, this includes the increasing engagement of private consultants (e.g. design and architectural experts) who also assume the role of urban manager. The justice struggles over Folkets Park have also evolved, and always in interaction with shifting managerial efforts to remake the urban space. When the park was first established, it symbolized a struggle over distributional justice to attain and normalize green, open spaces in low-income neighbourhoods. In later years, struggles to retain the park expanded to issues of procedural justice, where especially resident activists worked to be included in decision-making over the park’s future. Today, Folkets Park’s legitimacy as an open, green space for its residents appears beyond reproach, as does residents’ inclusion in renewal processes, and in this sense some justice struggles have been successful. The legacy of activism and longstanding commitment to inclusivity remains anchored in the neighbourhood through institutions like Folkets Hus. The power and influence the activist community has in securing an allocation of scare urban resources is most obvious in their material ‘wins’ like the park and financial support from the municipality. But the activists also maintain a discursive presence in Nørrebro, hosting frequent social and political events to publicly articulate their stance for social justice. Gaining and maintaining recognition of vulnerable residents’ needs amidst business as usual urban development still requires perpetual pushback to powerful urban elites (Mayer, 2017). Activists have thus demonstrated throughout time, that the right(s) to the city are hard-won, requiring sustained effort in demanding the just allocation of resources (ibid), even as urban managers incorporate justice perspectives into their approaches.

Struggles for recognition, which have occurred throughout, are also evolving, with more user groups expressing their legitimacy and asserting competing claims over the park. Conflict is no longer confined to city authorities-vs-local residents but rather cuts across residents, where different groups struggle vis-à-vis one another, to shape their corner of the city and to be recognized by urban managers. The park’s renewal also seems to have contributed to an unlikely convergence of interest toward the expulsion of the homeless, between at least some of the ‘gentrifying’ class and gang-affiliated residents. While their strategies differ, both groups exercise substantial power and claim legitimacy due not least to their residence status. That ‘green’ projects contribute, even unintentionally, to both gentrification and/or to stricter application of the law (Anguelovski, 2015; Dooling, 2009), is giving rise to interactional and distributive injustices anew. Green spaces have become integral to neoliberal transformations in Copenhagen, playing a role in strategies aiming to ‘sell the city’. In the context of such larger trends, Folkets Park seems to have been co-opted – especially in its ‘renewed’ form – into the wider, ‘deliberate’ gentrification agenda for the neighbourhood (Hansen and Karpantschof, 2016:185; interview with Copenhagen Municipality architect (ID 01)). Such ambitions impinge upon even the ‘best’ efforts by urban managers.

When looking at the relationship between activists and changing urban managerialism as we have done, it appears that the location of activism has broadened/become dispersed. As Copenhagen undergoes neo-liberalization, additional private actors – often sensitive to justice concerns – enter the field of urban planning. This could suggest a professionalization of justice, which risks excluding those it ostensibly aims to serve through (technocratic) expertise, as well weakened accountability of private decision-makers removed from traditional public sector mechanisms (Mayer, 2017). In contrast to past decades, the 2014 renovation of Folkets Park, driven both by public and private urban managers, appeared to be a planning and participatory success, in some ways resolving past injustices. The managers took inclusion seriously – even to the point of fighting for elements (e.g. lighting) that favoured marginalized groups. Yet we inquired of some in the design team as to whether the violence against the homeless that flared in 2017 tempered the renovation success. They defended their efforts by referring to the overall increase in users. We also found most urban managers uncertain or reluctant to discuss the role of urban and park renewal in neigbourhood gentrification. These are just examples of how, despite the evolution in policy, sector-based tunnel vision and simplistic assessments persist. Private urban managers (contractors) also compete for municipal funding, and hence face disincentives to rock the boat in terms of demanding particular procedures or park functions. Moreover, they simply cannot compete with powerful rhetoric from the city mayor or nationally dispersed rhetoric from e.g., xenophobic political parties coupled with austerity measures that dismantle services for vulnerable groups. In Copenhagen, there is a widespread lack of resources for adequate homeless shelter and service programs (Project Udenfor, 2012). At the national level, Denmark is embroiled in political debate around the nature of ‘Danishness’, with divisive narratives employed by xenophobic and/or market-oriented political parties that exacerbate the exclusion of non-European migrants and their descendants (e.g. Myong and Bissenbakker, 2016). This isolation and resulting disparity perpetuates social challenges like homelessness and gang affiliation. As such, the energy and resources spent toward inclusive, participatory urban planning processes and outcomes may be rendered lost. And despite the success and the interesting lessons the 2014 renewal offers future initiatives, Nørrebro residents still showed reluctance to be entangled once more in such processes. Finally, it is still the urban managers who largely define environmental/spatial needs and determine the scope of participation within these boundaries. This stands in contrast to some residents’ more immediate interest in addressing the needs of the vulnerable in the area. As Copenhagen positions itself as open and inclusive, this also brings into question whether participation, and perhaps even elements of environmental justice, have become indispensable to city branding in the arena of competitive urbanism, and whether genuine attempts at justice simply hit the neoliberal glass-ceiling (Mayer, 2017).

This brings us to the question of whether ‘spaces for all’ is a legitimate goal given the contradictions between municipal rhetoric and reality. The boundaries of tolerance are certainly put to the test in Folkets Park, and ambitions to accommodate everyone seem – even unintentionally – to facilitate co-option of desirable spaces by elites. The question of unintended ‘bad’ outcomes is even more striking if we consider the ramifications of trendy renewal projects capturing limited resources as social support programs deteriorate. We call for the notion of ‘space for all’ so prevalent in urban planning and landscape architecture today, to be replaced with a policy of spaces for all. We consider the notion of spaces for all as an iteration of the ‘spaces of difference’ conceptualized by Harvey (1996) – ensuring everyone has access to public spaces and facilities, including urban green spaces if indeed that is what communities desire, that provide the physical and psychological conditions which make diverse groups feel welcome.

Whose park will Folkets Park be in the future? Inevitably, this depends on the power of those laying claim to it, including the extent to which their values align with dominant trends in the country at a given time. To researchers, we call for the greater uptake of justice frames, and following Pahl’s advice, greater support to urban managers in seeing how the city is a reflection of distribution of power both present and past. As this case makes clear, even ‘good’ planning practices are a panacea neither for urban environmental injustices nor for creating spaces for all. What can concerned urban managers learn from this case? Pahl (1970:257) wrote, “The planner’s claim to optimise on behalf of society is nonsense”. We believe urban managers must acknowledge that planning must be political, and that conflict is part of the ‘good’ and democratic city (ibid.). Fully acknowledging the limitations of even their ‘best’ work, managers must break free from their disciplinary silos, working across sectors to better anticipate and prevent potential harmful outcomes and asking tough questions like: Who does this space serve? Who should it serve? According to whom? Finally, and in our opinion most critically, urban managers must also exit the confines of their ‘expertise’ altogether, to engage as resident activists in the politics and justice struggles of their own cities. If anything can be learned from activists’ efforts in Folkets Park over the last four decades, it is that only through messy conflict and debate that overarching dilemmas of resource allocation and recognition stand a chance of being eased. The activists of Nørrebro also remind us that justice hangs perpetually in the balance – thus the struggle never ends.

Anonymised respondent IDs and date of interviews

We thank Jevgeniy Bluwstein and Jens Friis Lund for their constructive comments, and all respondents and activists – our neighbors – in Nørrebro. Part of the research for this project received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. GA678034).

Rebecca L. Rutt, Rolighedsvej 23, 1958 Frederiksberg, Denmark. Email: rlr@ifro.ku.dk

Agger, A. Andersen, H.S., Engberg, L. and Larsen, J. N. (2000) Borgerdeltagelse og inddragelse i byomdannelsen. SBI-Meddelelse 126. Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut, Danmark.

Agger, A. and Hoffman, B. (2008) Borgerne på banen– håndbog til borgerdeltagelse i lokal byudvikling. Danmark Velfærdsministeriet.

Aitken, D. (2012) Trust and participation in urban regeneration. People, Place and Policy, 6, 3, 133-147. CrossRef link

Anguelovski, I. (2015) From toxic sites to parks as (green) LULUs? New challenges of inequity, privilege, gentrification, and exclusion for urban environmental justice. Journal of Planning Literature, 31, 1, 23-36. CrossRef link

Balfelt, K. (2016) Udvikling af Folkets Park af Kenneth Balfelt Team og Spektrum Arkitekter. [Video]. Available at: https://vimeo.com/207077598 [Accessed: 01/02/18]

Balfelt, K. (2018) Kenneth Balfelt Team: Vision. Available at: www.kennethbalfelt.org/ [Accessed: 12/06/18].

Burrows, R. Webber, R. and Atkinson, R. (2017) Welcome to ‘Pikettyville’? Mapping London’s alpha Territories. The Sociological Review, 65, 2, 184–201. CrossRef link

Christensen, E. (2014) Områdefornyelsen Fortæller. Ministeriet for By, Bolig og Landdistrikter.

CPH Post (2012) Four attacked in Folkets Park. Available at: cphpost.dk/news/local-news/four-attacked-in-folkets-park.html [Accessed: 12/18/17]

Crow, G. and Takeda, N. (2011) Ray Pahl’s Sociological Career: Fifty Years of Impact. Sociological Research Online, 16, 3, 11. CrossRef link

Dansk Byplanlaboratorium (1996) Byfornyelse fra gadegennembrud til integreret byfornyelse 10. Byplanhistoriske Noter 31. Gammel Dok, København.

Detter, D. and Fōlster, S. (2017) The Public Wealth of Cities: How to Unlock Hidden Assets to Boost Growth and Prosperity. Brookings Institution Press.

Dooling, S. (2009) Ecological gentrification: a research agenda exploring justice in the city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33, 3, 621–639. CrossRef link

Dyck-Madsen, S. (2004) Kampen om Byggeren på Nørrebro 1980. Folkets Hus. Available at: www.folketshus.dk/byggerbogen/Byggerbogen-webudgave.PDF [Accessed: 12/18/17]

European Commission (2018) Nature-Based Solutions. Available at: ec.europa.eu/research/environment/index.cfm?pg=nbs [Accessed: 22/11/18].

Folkets Hus (2004) The history of People’s Park. Available at: www.folketshus.dk/park/historie.htm [Accessed: 12/13/17]

Forrest. R, and Wissink, B. (2017) Whose city now? Urban managerialism reconsidered (again). The Sociological Review, 65, 2, 155–167. CrossRef link

Fraser, N. (2009) Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World. Columbia University Press.

Hansen, A.L. and Karpantschof, R. (2016) Last Stand or Renewed Urban Activism? The Copenhagen Youth House Uprising, 2007. In: Mayer, M, Thörn, C and Thörn, H (eds) Urban Uprisings: Challenging the neoliberal city in Europe. Berlin: Springer: 175-201. CrossRef link

Hartvigson, P. (1993) 1993 – byvandring på randen af historien. Byhvandring.nu. Available at: byvandring.nu/vejviseren/samtidshistorie-1993/ [Accessed: 05/05/17]

Harvey, D. (1989) From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism. Geografiska Annaler, B, 71, 1, 3–17. CrossRef link

Harvey, D. (1996) Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers.

Hecklen, A. (2017) Gadejurist: Rydninger af hjemløselejre holder ikke i retten. Available at: www.dr.dk/nyheder/indland/gadejurist-rydninger-f-hjemloeselejre-holder-ikke-i-retten [Accessed: 12/18/17]

Indlændinge-, Integrations- og Boligministeriet (2016) Byg dem op. Report. Available at: www.trm.dk/-/media/files/publication/boligpublikationer-til-2016/byg-dem-op.pdf [Accessed: 22/11/18]

Ingvorsen, E.S. (2017) Midt i bandekrigen. DR (Danish Broadcasting Corporation) Available at: www.dr.dk/nyheder/indland/midt-i-bandekrigen-flere-soeger-vaek-fra-mjoelnerparken [Accessed: 12/14/17]

Justitsministeren (2017) Lov om ændring af straffeloven: lovbekendtgørelse nr. 1052 af 4. juli 2016. Available at: www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/r0710.aspx?id=192080. [Accessed: 06/06/17]

Juul, K. (2017) Migration, Transit and the Informal: Homeless West-African Migrants in Copenhagen. European Journal of Homelessness, 11, 1, 131-151.

Katz, B. and Noring, L. (2017) The Copenhagen City and Port Development Corporation: A model for regenerating cities. Research Report. Washington D.C., Brookings Institution.

Koefoed, E. (2014) Folkets Park, third edition. Magasinet Kbh. Available at: www.magasinetkbh.dk/indhold/folkets-park [Accessed: 12/14/17]

Københavns Kommune (1979) Helhedsplan 1979 Indre Nørrebro. Kooperative Byggeindustri.

Københavns Kommune (1996) Bydelsatlas Nørrebro – Bevaringsværdier i byer og bygninger 1996. Miljø- og Energiministeriet, Skov og Natur Styrelsen, og Københavns Kommune.

Københavns Kommune (2004) Lokalplan nr. 215. ”Stengade II” Indre Nørrebro. Bygge- og Teknikforvaltningen.

Københavns Kommune (2005) Fornyelse af Folkets Park – Program. Københavns Kommune Vej & Park.

Københavns Kommune (2010) Bland Dig i Byen – Medborgerskab og Inclusion: Integrations Politikken 2011-2014. Beskæftigelses- og Integrationsforvaltningen.

Københavns Kommune (2011) Sikker By – Mindre kriminalitet og mere tryghed 2010-1014. Sikker By strategien, Center for Byudvikling.

Københavns Kommune (2012) Policy for Disadvantaged Areas of Copenhagen. Technical and Environmental Administration.

Københavns Kommune (2015a) Integrationspolitik 2015-18. Social Mobilitet og Sammenhængskraft. Beskæftigelses- og Integrationsforvaltningen.

Københavns Kommune (2015b) Fællesskab København. Teknik og Miljøforvaltningen.

Københavns Kommune (2015c) Bynatur i København – Strategi 2015-2025. Center for Bydækkende strategier.

Københavns Kommune (2018) Sikker By strategi 2018-2021. Center for Byudvikling.

Larsen, H. G. and Hansen, A. L. (2008) Gentrification-Gentle or Traumatic? Urban Renewal Policies and Socioeconomic Transformations in Copenhagen. Urban Studies, 45, 12, 2429-2448. CrossRef link

Larsen, J. E. and Möller, I. H. (2013) The increasing socioeconomic and spatial segregation and polarization of living conditions in the Copenhagen metropolitan area. Presentation to the RC 19 Annual Conference of Research Committee 2013, ISA, Budapest, Hungary, 22‐24 August.

Lewis, V. (2016) All of the Coolest Spots in Copenhagen Are on This Street. Vogue Magazine. Available at: www.vogue.com/article/jaegersborggade-copenhagen-guide-coolest-street [Accessed: 12/10/17].

Low, S. (2013) Public Space and Diversity: Distribution, Procedural and Interactive Justice for Parks. In: Young, G, and Stevenson, D (eds) The Ashgate Research Companion to Planning and Culture. Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate. 295–310.

Low, S. and Iversen, K. (2016) Propositions for more just urban public spaces. City, 20, 1, 10-31. CrossRef link

Mayer, M. (2017) Whose city? From Ray Pahl’s critique of the Keynesian city to the contestations around neoliberal urbanism. The Sociological Review, 65, 2, 168–183. CrossRef link

Myong, L. and Bissenbakker, M. (2016) Love Without Borders? Cultural Studies, 30, 1, 129-146. CrossRef link

Nørrebro Lokalhistoriske Forening og Arkiv (2018) Postkort Fra Nørrebro. Available at: noerrebrolokalhistorie.dk/postkort.php [Accessed: 06/06/18].

Områdefornyelsen Nørrebro (2014) Kvarterplan 2014-2019. Teknik- og Miljøforvaltningen, Københavns Kommune.

Øvig Knudsen, P. (2016) BZ – du har ikke en chance – tag den! – et familiedrama. Gyldendal.

Pahl, R. E. (1970) Whose City? And Other Essays on Sociology and Planning. London: Longmans.

Pahl, R. E. (1975) Whose City? And Further Essays on Urban Society. 2nd edn, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Pedersen, M. L. and Lindstad, J. M. (2011) Første Led I Fødekæden? En undersøgelse af børn og unge i kriminelle grupper. Rapport. Justitsministeriet.

Politiken (2014) Politiets behandling af flaskesamlere er grotesk. Available at: politiken.dk/debat/ledere/art5553804/Politiets-behandling-af-flaskesamlere-er-grotesk [Accessed: 12/09/17].

Project Udenfor (2012) Report on homeless migrants in Copenhagen. Copenhagen, Denmark.

Rose, J. (2017) Cleansing public nature: landscapes of homelessness, health, and displacement. Journal of Political Ecology, 24, 1-124. CrossRef link

Rutt, R. L., and Gulsrud, N. M. (2016) Green justice in the city: a new agenda for urban green space research in Europe. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 19, 123-127. CrossRef link

Schlosberg, D. (2007) Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford University Press. CrossRef link

Schmidt, G. (2015) Space, politics and past–present diversities in a Copenhagen neighbourhood. Identities, 23, 1, 51-65. CrossRef link

Schmidt, G. (2017) Going beyond methodological presentism: examples from a Copenhagen neighbourhood 1885–2010. Immigrants & Minorities, 35, 1, 40-58. CrossRef link

Sheikh, J. (2015) Frank Jensen vil af med hjemløse, der sviner. Available at: politiken.dk/indland/art5576645/Frank-Jensen-vil-af-med-hjeml%C3%B8se-der-sviner [Accessed: 12/09/17].

Sikor, T., Martin, A., Fisher, J., He, J. (2014) Toward an Empirical Analysis of Justice in Ecosystem Governance. Conservation Letters, 7, 6, 524–532. CrossRef link

Steiger, T. (2017) Cycles of the Copenhagen Squatter Movement: From Slumstormer to BZ Brigades and the Autonomous Movement. In: Martínez López, M A (ed) The Urban Politics of Squatters’ Movements: 165-186.

Tholl, S. (2017) In Copenhagen, a “People’s Park” Design Includes Dark Corners. Next City. Available at: nextcity.org/features/view/copenhagen-park-design-includes-dark-corners [Accessed: 12/08/17].

Toft, E. (2017) Hvad er Loyal to Familia? DR. Available at: https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/indland/hvad-er-loyal-familia-selv-advokaten-har-ikke-et-klart-svar [Accessed: 12/18/17].

Tromborg, M. (2013) Folkets Park på Nørrebro skal renoveres – igen. Available at: www.mx.dk/nyheder/kobenhavn/story/24387434 [Accessed: 12/08/17].

Vedel, P. (2014) Byens broer og bombekratere. Guest post. Den Fri. Available at: www.denfri.dk/2014/05/byens-broer-og-bombekratere/ [Accessed: 12/14/17].

Vestergaard, H. (2016) Almennyttige boliger. Den Store Danske, Gyldendal. Available at: denstoredanske.dk/index.php?sideId=36262 [Accessed: 12/15/17].

Visit Copenhagen (2017) Nørrebro: colourful, casual and young at heart. Available at: www.visitcopenhagen.com/copenhagen/culture/multicultural-norrebro [Accessed: 15/01/18].

Walker, G. (2012) Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics. London: Routledge. CrossRef link

Zucchino, D. (2016) ‘I’ve Become a Racist’: Migrant Wave Unleashes Danish Tensions Over Identity. New York Times. Available at: www.nytimes.com/2016/09/06/world/europe/denmark-migrants-refugees-racism.html [Accessed: 04/06/18].