Abstract

Research on public access to urban green space tends to focus upon access-takers’ motives and meaning-making. The motives and meaning-making of the owners and managers who control such spaces are rarely examined. To address this deficit this article presents a longitudinal case study examining how an owner’s ambivalent stance over public access to his public house’s exterior ‘beer garden’ area arose from its (and his) habitus. The case study shows how the owner came to unwittingly present this as an uninviting and ambiguous urban green space by inheriting and perpetuating a pre-existing, habitual encoding of territoriality at his struggling, city-fringe commercial premises. In interpreting this ambivalence, the article examines the influence of both local and wider structural factors showing how both material traces of prior ordering and the owner’s pragmatic understandings of liability and risk shaped this place, and made it simultaneously appear both open and closed to public access.

Introduction

Myriad recent research (e.g. that surveyed in Dennis and James, 2016), and policy announcements (Public Health England, 2014), have emphasised the social, environmental and wellbeing benefits of public access to urban green space. Much of this research has been attentive to examining the motives and meaning-making that inspires or deters members of the public from engaging with such spaces (Özgüner, 2011). In contrast the motives and meaning-making of owners of urban green spaces have been the subject of far less investigation. In particular, commercial owners have only been glimpsed in most studies, as faintly sketched assumed-to-be ultra-rational actors whose actions are guided relentlessly towards the privatisation of once-public spaces by the capitalist logics of accumulation and profit maximization (Mitchell, 2003; Harvey, 2008; Minton, 2009). However, as the following case study will show, whilst no-doubt of importance, the profit motive alone is not the sole determinator of why commercial owners do or do not provide public access to their lands. Other factors, like fear of liability of accidents and received notions of propriety, privacy and familiarity, all have the ability to haunt and pre-occupy owners in their framing of decisions about access to their urban green spaces.

A lack of sustained attention to investigating the actual motives and meaning-making of those who provide (or deny) public access to urban green space is a weakness in existing scholarship. If provision of urban green space is to be maximised then a more nuanced understanding of how the diverse spectrum of owners actually think and act regarding access to their land is needed. Only by understanding their motives and meaning-making, can owners be most effectively engaged and encouraged by publics and policy makers alike, to maintain (and hopefully increase) their contribution towards the provision of urban green space.

Accordingly, this article presents a single-site, longitudinal case study which seeks to examine the motives and meaning-making of the owner of one commercial site, in pursuit of the following research question: ‘how does an autonomous-seeming site owner form and implement his attitudes towards the provision and management of his urban green space?’ This question grew out of my related wider investigations into cultures of anxiety amongst rural and urban landowners about the perceived risks of allowing public access to their open spaces – specifically rural land (Bennett & Crowe, 2008), cemeteries (Bennett & Gibbeson, 2010), urban forestry (Bennett, 2010) and an art park (Bennett & Crawley-Jackson, 2017). The single-site approach used here was a way of looking closely at how collaborative meaning-making processes observed in my earlier studies ‘trickled down’ to shape access to an individual local site.

In its concern with explicating logics of meaning-making, this study is situated within an interpretivist paradigm. My aim is to present a “thick description” of sense-making in a place-situation (in the spirit of Rottenburg, 2000: 88), and to use this as a vehicle for suggesting ways in which the study of access control to open spaces could be widened. The case study presented here was limited in scale and opportunistic, for this was an ambiguous space observed whilst regularly walking my dog passed the site during the study period, augmented by occasional forays into the pub itself (‘pub’ is a commonly used British abbreviation of ‘Public House’, a commercial venue at which to gather, socialise and drink alcohol known variously elsewhere in the world as a ‘bar’, ‘inn’ or ‘cantina’). My data was gathered by means of photography of the site each time its presentation to the world appeared altered, my own phenomenological experience over this period of the study-space’s increasingly anomalous disposition and a semi-structured interview of one of the succession of owners who briefly ran this establishment. Accordingly, the interpretations presented here are tentative, but the data gathered presents a provocative basis from which to explore aspects of access that are rarely examined in contemporary studies of public space. But before turning to the specifics of the case study we must briefly consider the ways in which existing scholarship has approached the study of owners’ motives and meaning-making about public access to their green spaces, and particularly, to see what evidence can be found for a fear of liability being the key driver of owners’ access-restricting behaviours.

Why do owners have a problem with access to their green spaces?

Studies of the restriction of access to urban green spaces have tended only to be incidental aspects of broader, critical enquiries into contemporary urban enclosure processes. The main focus of these studies has been upon understanding the withdrawal of elites to gated communities and charting the wider political economy of larger scale urban enclosure processes: the rise of privatised public spaces such as shopping malls and the proliferation of heightened security and surveillance regimes in urban centres. These studies have tended to identify the roots of urban enclosure in a combination of contemporary fears of crime and ‘others’ (e.g. Low, 2004; Minton, 2009; Atkinson and Blandy, 2017) and in the ’accumulation by dispossession’ spatial logics of late capitalism (Harvey, 2008: 34). The interpretive arc of such studies has been towards explicating the ingenious spatio-legal manoeuvres (Layard, 2010) by which this enclosure is implemented, and the democratic deficit resulting from the increasing loss of urban spaces of public gathering and circulation, in the face of which a ‘Right to the City’ is asserted (Mitchell, 2003). But, apart from quizzing residential landowners about their motives for withdrawal from public spaces, these urban focussed studies have tended not to directly enquire into the access-curbing motives or meaning-making of urban green space owners.

However, some assistance can be gleaned from a handful of existing survey-based studies examining how landowners think about public access to their rural green spaces (Teasley et al., 1997; Gentle et al., 1999; Wright et al., 2002), albeit that most of these studies have related to the US experience (and its different topographic and legislative context) and therefore may not be directly indicative of UK motives and meaning-making. These US studies were motivated by a concern by policy-makers that, even after legislative concessions had been made at state and federal level, rural landowners were still using stated fears of liability as a reason for prohibiting recreational access to their land. This implied at best that the owners were struggling to understand the applicable liability rules and at worst that such behaviour was the product of a wilful desire by owners to misinterpret (to themselves) or misrepresent (to their audience) the impact of liability-risk upon their site access decision-taking. In short, that it was a cover for some other motivation.

Gentle et al’s (1999) investigation considered whether the different political and cultural heritage of various US States influenced landowners’ attitudes towards provision of access. But they found no clear patterns in their data other than that ‘landowners are much more comfortable with the use of their land by friends and family, rather than by strangers’ (Gentle et al., 1999: 57) and that a history of ‘unpleasant experiences with recreationists’ (62). Meanwhile Teasley et al (1997) had found respondents giving a variety of reasons for prohibiting access to their land, many of which could be grouped under a collective heading of ‘keeping land private’, with only 28 per cent agreeing that their decision was in whole or in part ‘to protect me from lawsuits’.

There has been little research in the UK into the role of fear of liability in shaping landowners’ attitudes to recreational access. The limited UK studies also suggest that fear of liability may be a much lesser influence than perceptions of privacy and control. For example a study of woodland owners’ attitudes to access in the South East of England for the Forestry Commission (2005) found that one third of private non-forestry business owners felt that their woodlands were important for personal privacy, with over 75 per cent of this group reporting a perceived ‘loss of control’ if public access was allowed.

Thus, just as caricaturing owners as ‘simply’ acting out profit-maximising behaviours appears to offer an incomplete interpretation, so does a legalistic assumption that owners are solely acting out an equally rationality-inspired liability risk management calculus when limiting access to their green spaces. Instead, other less tangible factors such as privacy and prior experience appear to have important roles to play, and not necessarily in a way fully perceptible to the owners themselves. For instance, risk aversion may persuasively function at a sublimated, un-thought level. In this regard, mapping out what we might call the ‘anxious-turn’, variously Landry (2005), Bauman (2006) and Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos (2007) have each pointed to the recent rise of an ‘anticipatory fear’ in late modernity – a future focussed, risk assessment-shaped, attempt to prescribe for the adversities of the (near) future. In this cultural milieu pervasive, inchoate and contingent anxieties are articulated by respondents in what seems to them the most appropriate, culturally acceptable framings (Wildavsky and Dake, 1990). Thus the prevalent discourse of safety, risk and liability may be a more palatable way for owners to publicly articulate their decisions about access control to their land rather than to present their rationale in the language of privacy, familiarity and dominion.

In a UK context, perhaps something similar (the surfacing of a wider, inchoate anxiety) is revealed by respondents to surveys undertaken at the time of proposed legislative extension to prevailing recreational access rights to privately owned rural green spaces. Thus a 2011 study of farmers’ anxieties about proposals to introduce a statutory right of recreation access to their land in Northern Ireland (Northern Ireland Assembly, 2013) showed a persistence of a stated fear of liability for any accidents suffered by access-takers, despite reassurance that risk of compensation claims was demonstrably low. Meanwhile, in England a survey conducted by a pressure group, the Country Landowners and Business Association (CLA, 2007), aimed at gathering and presenting to Government evidence of landowners’ concerns about the feared impacts of the then proposed coastal ‘right to roam’ (eventually enacted via the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009) saw landowners invoking a colourful array of contemporary ‘folk devils’ (Cohen, 2011) to illustrate their fear of the adverse consequences that the proposed public access legislation would bring: burglars, doggers (and also dog walkers), paedophiles, vandalism, unexploded bombs, errant golf balls and the perils of coastal erosion. This list of worries testifies to the diversity of rural (and coastal) landowners and the myriad ways in which anxiety about a change in access legislation may be expressed in, amongst other things, the language of safety and liability fears. Thus, and as the case study will show, whilst we might expect an owner to ‘name-check’ risk and liability anxieties when asked about their stance to access to their green spaces – because this is a dominant discursive formulation – whether that issue actually has a strong motivating power over the owner’s access-related actions is far harder to establish.

Towards the paddock

Scholarship to date has observed a fairly rigid distinction between rural and urban investigations, with empirical studies of the control of recreational access to the countryside on the one hand and more theoretically inclined studies of urban enclosure processes on the other. However, in reality much land lies between the extremes of rural idyll and dense city block. Indeed, as Farley and Symonds-Roberts (2011) note, the greatest level of contestation over day to day access to green spaces may actually lie in the ambiguous ‘edgelands’ – the car parks, urban-fringe fields and woodlands, wastelands and ruins at which neat and stable classification of such spaces as unquestionably ‘rural’ or ‘urban’ or exclusively ‘public’ or ‘private’ will often prove unworkable. This article therefore seeks to contribute towards breaking down this polarisation by presenting a case study of access management to the grounds of a city-fringe pub which draws both from the empirical tradition of the rural studies and the critical-theoretical sophistication of the urban investigations.

In 2009, as part of my ongoing studies into the pragmatics of owner attitudes towards public access to their land, I decided to subject a local edgelands site to a site-specific investigation. I intended that this would be an inquiry into the motives and meaning-making of a person actually occupying and managing a specific site: someone who was interpreting and taking action ‘on the ground’. The aim was to come to see the site and its ordering through the manager’s eyes, and thus to see their ‘working’ notion of the law’s requirements regarding public safety in the context of access to a privately owned urban green space. However, once underway it quickly became clear that piecing together the story of the site would require more than accessing the site manager’s own account, it would also require an interrogation of the site itself, both materially and symbolically, and consideration of its wider socio-economic context.

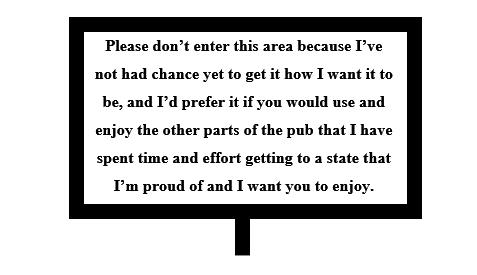

The case study site was a local, city-fringe Sheffield pub which I had already been aware of for ten years and which during that time had passed through a number of different owners. The pub had a grassed area, called ‘the paddock’ separated from the main pub building and its immediate courtyard by an access driveway. Although referred to by the publican as ‘the paddock’, no horses had been there for at least ten years, and that space’s own name was an early indication of the ways in which the past can continue to dictate how a place is presented to the world. The paddock comprised a small wooden fenced plot and contained a couple of old but functional wooden picnic tables. There were no obvious hazards there, however over the previous decade I had observed that each successive owner had sought to single this seemingly unremarkable green space area out as noteworthy and awkward by affixing successive layers of cautionary signage to the fence that bounded this supposedly commercial, public zone as a beer garden (Figure 1).

In 2009 I secured an interview with the then current owner, and set about asking him about how he had come to know how to present his pub to the world. I thought that the publican would be able to provide a conscious, rational explanation of the accretion of signage at the threshold of the paddock – perhaps by recounting a previous accident in, or complaint about, the paddock which had set the whole sign affixing process off. I also thought there might be some indication, in the publican’s account, of safety/liability fears presenting as a proxy for a deeper set of territorial concerns (e.g. privacy and/or fear of loss of ‘control’).

But from the interview it became clear that the story of the field was that there was no story, at least not so far as the publican could account. Whilst he duly echoed contemporary ‘common sense’ discourse about the self-perpetuating nature of safety regulation and expressed the view that we live in an era of increasing (and spurious) compensation claims he did not appear fearful of any such proceedings. He had had no personal experience of such regulatory intervention or claims, and appeared confident in his ability to manage people and situations through his own ‘good host’ nature (rather than stating an affinity for forms, barriers or notices). Neither ‘insurer requirements’ nor even the requirements of his premises licence had much effect upon how he described his approach to management of the paddock. Nor did he appear to be haunted by a fear of his patrons and what they might get up to around his pub. Indeed he portrayed a particularly optimistic worldview, appraising the likely behaviour of those who may come into the vicinity of his pub by reference to his own easy-going character and adaptive background.

Yet despite all of this the paddock was arrayed with cautionary signs and disclaimers, giving it every appearance of a place into which the public was not invited. But the publican’s best account of his actions in ‘closing’ the field was that the area was ‘untidy’ and not somewhere that he would use himself at the moment. On being pressed for further explanation, he dismissively added that the signs were ‘just a risk assessment…just health warnings’.

Interpreting the story

The interview revealed that the field was an area of the publican’s premises that was not at the forefront of his mind or the forefront of his plans for his business. He would turn his attention to that area someday. Until then he had written it off in his mind as ‘untidy’ and not somewhere that he would want to go if he were visiting this pub as a customer. It appeared that he regarded it as a ‘non-place’ (Augé, 1996), in his mind, focussed as it is on building a viable business at this rather marginal location, it was (or at least he wanted it to be) ‘out of mind’, and because it was meaningless space to him he could not comprehend that anyone else might properly find that space desirable at the moment. Yet, for some unarticulated reason he felt compelled to reinforce the abandonment of that space by recourse to signifiers of risk and liability.

At a number of points in the interview the publican mentioned the inevitability and/or the business advantage of taking things on as they are – and not seeking to change everything from the start; for example, he said:

‘…here you’ve got to be kid friendly where we are, in like the Tap Room you’ve got to be dog friendly: because that’s how it’s always been…so it’s easy for me to come and say ‘I’m not having any dogs in there’ – but it’s not; its part and parcel of this, the history of the pub I suppose’ (emphasis added)

This, in the spirit of Bourdieu (1987), suggests a form of habitus, an embedded physical manner of use of a place by its owner and its patrons which it is difficult – or inadvisable – to change. It is embedded history and knowledge that makes the place what it is; it is the accumulated impressions that a local populace have of that place and the normative order expressed and embodied within it.

The ‘story’ of the field, then is actually that the signified conditions of this place (the warning signage and appearance of exclusion) have been inherited circumstantially from previous owners via the existing manner of physical arrangement of the pub and its grounds. There is no great thought behind it. This disposition-as-place exists, remains and is added to because there has been no event or cause to alter that status quo or challenge its appropriateness.

At this pub this habitus appears primarily encoded and transmitted between successive owners through the physical arrangement of the place, for there was minimal induction of the publican by the previous owners on hand-over. The publican thus appears, via a process of ‘sedimentation’’ (Berger and Luckmann, 1971: 85), to have added his own extra layers of signage, by recycling, repeating or adapting phrases inherited from his predecessors’ notices (see Figures 2 and 3).

For Bourdieu, habitus can reside in both places and people, and in both cases habitus is at least partially external to the local situation. Wider socio-economic (and other normative) influences will play their part in setting the appropriate dispositions for those people in that place.

The recent history of the pub industry is one of rapid (and externally imposed) structural change as Mutch (2000, 2001 and 2003) and Pratten (2007a, 2007b) show. In 1913 95 per cent of licensed properties were brewery owned but during the twentieth century this domination progressively declined. The process accelerated following a Monopoly & Mergers Commission investigation in 1989 (MMC, 1989) that led to large brewers being forced to divest many of their pubs, prompting the creation of new, smaller pub portfolio owning groupings (‘Pubcos’), many funded by investors from outside the brewing industry. Since the early 1990s the pub sector has been subject to multiple waves of ownership change as banks, venture capitalists and entrepreneurs have regularly traded Pubco portfolios. The rising market share of supermarket alcohol sales and waves of legislative change such as the liberalisation of pub opening hours since 2002 and the indoor smoking ban introduced in 2007 have also contributed to the atmosphere of constant change within the sector.

Set against these waves of externally imposed change publicans have struggled to keep their pubs open, with marginal pubs now divested from the breweries and Pubcos and operating in isolation as independent ‘free houses’. We may conjecture that the consequent break-up of long-term pub chains, reduced career stability for employed pub managers and the hiving off of marginal pubs to incomer owner-managers (as was the case with the study pub) may all have worked to undermine traditional, stable interpretations of occupiers’ liability law as applied to pubs. Instead the ensuing semantic instability has opened up the prospect of an anomic ‘do it yourself’ type ethos, one in which each publican must either bring in interpretations from outside the sector (e.g. from manufacturing environments) or opt for slavish perpetuation of whatever they find sedimented within the pub’s existing physically arrangement.

Indeed, a pub is a complex set of ordained spaces – often with distinct designated bar areas (the ‘public bar’, the ‘tap room’ and the ‘lounge’) each customarily assigned different decor, physical arrangement, customer expectations and behavioural norms. Add to that the temporal and activity-regulating aspects of the Licensing Acts and it becomes clear that running a pub is all about knowing how to respect and reproduce the ‘expected’ designation of times and spaces, and the control of activities and uses, within that place. Perhaps not surprisingly then, the first place a new manager will look for guidance on what he must do, is the material culture and existing arrangement of the pub itself, as an embodiment of those normative codes and expectations.

So, in a pub we find an industry sector built firmly upon habitus. But now this industry traditionally framed in unwritten tradition and an expectation of the publican ‘learning on the job’ has been shaken recently by cumulative waves of recent externally imposed change and competition. Those collective certainties have lost much of their strength and publicans must increasingly act autonomously, and desperately, in order to survive. Indeed, during the interview the publican repeatedly alluded to difficulty he was facing in making his business venture a success. My talking about the paddock, and asking him to account for how he was perceiving and managing liability risk for this ‘non-place’ must have felt perplexing to him. Despite my dogged line of questioning the economic pressures and uncertainties continually irrupted during the interview.

Within months of the interview the publican’s venture was at an end, and the pub had new owners. However, and in testament to the inertial power of the pub’s habitus, this change of ownership wasn’t easy to spot. The incoming owners made no changes to the physical arrangement of the place, the brasses, the games box, the tables, the ancient photos of the pub in times past, along with the field’s signage, all remained there, unaltered. In this pub, the owners came and went but the place, courtesy of its habitus, lived on unchanged.

What can this case study tell us about owners’ motives for their access-managing actions?

The case study warns us that it would be dangerous to assume a coherent, rational motive behind owners’ actions or utterances about public access to their urban green spaces – and whether rooted in either profit maximisation or anxiety about liability risk. Instead the case study shows the power of habit as embodied in place and inculcated into actors through their prior experience and learning. It does not preclude an influence for either profit maximisation or risk of liability, but rather shows how the influence of these more rational, structural factors becomes sublimated into local ways of doing. Thus, as Andrews (2000) has noted (in relation to the ritual behaviours comprised in company directors’ compliance with their disclosure duties under UK Company Law) what may actually be driving apparent compliance (in the sense here of a cautious – warning sign based – approach to management of the paddock) is a learned performativity, a ritualised behaviour, rather than an internalisation of the law itself. Thus just as company directors learn how to remember to fill in the appropriate forms, so owners learn how to perform adherence to the conventional behaviours of territorial demarcation and risk management, but this is borne more of habit than deep understanding of the law’s conceptual doctrines.

Furthermore, in terms of the local translation of law into embodied on-site reality, the case study shows that, when we look, we may find that law’s concepts and symbols are deployed in day to day discourse (and its corresponding spatial action) in a distinctly approximate and incidental way. This interpretation chimes with Ewick & Silbey (1998) and Silbey (2005) investigations of lay, everyday legal consciousnesses. For them, law is an available schema, likely to be drawn upon pragmatically by citizens in order to make sense of their everyday lives, but it does not present a singular controlling code of living. In their studies law is commonly found to be subordinate to other normative (and situational) influences shaping conduct. This view also resonates with recent work in legal geography (Delaney, 2010; Braverman et al., 2013) which, drawing upon socio-spatial theorists like Lefebvre (1991), emphasises that ‘the legal’ and the spatial are co-productive and that the focus of that production is pragmatic action. Thus places, and behaviour within them is the outcome of a dynamic interaction between the material specificities of any space, its prevailing normative orders, and the tasks that people are seeking to achieve there.

Thus the paddock’s signs are weak indices of the body of law to which (for some) they point. How many passers-by would actually read all the way down to the bottom of the disclaimer sign presented in Figure 4?

Most would acknowledge it in a superficial way, such that it doesn’t actually matter what is specifically written on it. Such signs create (and defend) territory as much by their generalised normative appeal to moral and habitual (i.e. learned) notions of ‘a sign means private space’ rather than stopping to interrogate its indexical appeal to specific provisions of occupiers’ liability law. Indeed, the territorial intent of these signs is unclear, for they do not actually forbid entry. Instead they present the paddock – for no clear reason – as an exceptional, awkward space, a place into which entry has been designated as ‘complicated’, in comparison to the simplicity of the presentation of surrounding land.

The signs could have said ‘no entry’ but this might have seemed too brutal (or total) a prohibition given the ‘welcoming’ context that a pub will generally be expected to provide. Bottomley and Moore (2007) note the trend away from physical exclusion within city centre ‘privatised’ spaces, towards a more collaborative ‘governance’ based approach. Governance here is a term derived from Foucault (Lupton, 1999), which notes that the modern way of governing subjects is increasingly less achieved through barriers, official violence or even direct imposition of law, but rather relies upon processes by which subjects are conditioned to respond to ever more subtle cues of control. The discourse of risk is a particularly ascendant ‘disciplining’ discourse (Landry, 2005). In short, using the language of risk and danger may be a particularly contemporary, polite and effective way to achieve access control to ‘dead space’.

The fundamental point with the field is that the publican could not conceive of any other usage for that space. He would not want to go there (as a customer), he was not at the time of the interview ‘providing’ that space (in the sense of offering it as part of his commercial realm). It was at that moment meaningless to him (but has the potential for meaning in the future). He needed to symbolically nullify it, to take it out of the picture and to deal with it ‘later’. Yet he expressed that in the ‘modern way’ via the language of risk allocation and the persistence of inappropriate or mutated signs, that testify to a general deterrence, rather than a specific warning / thing of danger or an outright foreclosure of this space.

This nullification reveals an aspect of territoriality that may not seem obvious – something that Sack (1986: 33) describes as ‘place clearing’. Sack describes this form of territoriality in rather abstract terms, but in the case of the field we can see that territory can be a willed nullity. The publican has no current use for the space. Perhaps he can see some potentiality in it, but for the time being it is surplus to requirements. Perhaps we could argue that this behaviour is rooted in a capitalist logic of accumulation – a land-banking of sorts in which spaces are only presented to the public at times of the profit-seeker’s choosing. But that requires a more subtle understanding of accumulation than is currently to be found in most studies of urban enclosure, for here the site remained permeable, it was never fully or effectively withdrawn from the public domain. Instead it became, ambiguously, simultaneously both public and private.

As Sack (1986) notes, territoriality may be a relatively cheap and effort-free way of managing a spatial problem (in this case a spatial surplus). It is easier to deter the public from an area by affixing a few mildly unwelcoming signs than spending the time to render it ‘tidy’. And to extend the analysis here, it is easier for the publican to deter via a sign that invokes law, risk and danger (because people are more likely to take notice of that sign) than it would be to erect a sign that says (as might have been more accurate).

Remember here that the publican appears not to have any particular danger in mind other than ‘untidyness’. For him (if it is a conscious one at all) the role of the signage is to help keep the field off his list of things to worry about. It needs to be symbolically declared a ‘non-place’ for the time being whilst he focuses on trying to develop the pub’s core spatial zone (the pub’s bar rooms and its contiguous courtyard). The field now lies beyond that spatially shrivelled core, it’s ageing picnic tables a legacy of a previous expansionist era at this pub, an era during which – these remnants would suggest – an unsuccessful attempt was made to commercially colonise this marginal zone.

Here we see the creation of waste-land, a process of neglect underscored by a low-thought, low-cost, low-effort technique for declaring it empty and (in a commercial sense) not currently part of the pub. Yet, all the publican has to do is declare it a temporary ‘Beer Garden’ on special occasions and it springs back into being as a willed part of the pub. Bottomley and Moore (2007) have noted the increasing blurring of any rigid distinction between ‘public’ and ‘private’ space – instead spaces become multifunctional. Thus the field is neither ‘private’ nor ‘public’ in any static sense, instead it fluctuates and the borders that it sets up are porous because of the commercial imperative (and potential of the field on occasion, and perhaps more so in some indeterminate future) to be a space of commerce. In such situations the field can become (both physically and symbolically) ‘opened for business’.

Altman (1975) defines such places as ‘secondary territories’, places characterised by the ambiguity of their access status, due to their being neither for all time nor in all circumstances unequivocally ‘private’ nor ‘public’ space. These are places into which the public may enter sometimes. The rules of sometimes are complex and may need spelling out in notices and declarations of express conditions of access if the habitus of the place does not create clear normative guidance.

Yet, perhaps ironically the signs themselves can – via sedimentation – become ‘stuck’, enduring as a powerful material component of the pub’s habitus. Significantly, at this place, the local habitus does not appear to provide a clear framework for the removal of this signage.

As we have seen, at the time of my interview the publican’s sense of proprietorship over this area was weak, and he was taking (and perpetuating) things as he found them. Thereby this was a space controlled by circumstance, rather than by conscious direction on his part. There was no cynical exclusionary strategy here. Instead the process played out by default. Here these signs themselves controlled space, controlled visitors and – in the sense of habitus explored above – also appeared to exert some control over the successive owners of this place.

My best guess is that this sedimentation of signage was set in hand in the paddock many years earlier, by a previous owner. When I first became aware of the paddock in the early 2000s there had been vestiges of a rather rudimentary ‘adventure playground’ in the field. The haunting ‘take care for your children in this place’ atmosphere, perpetuated by the signage, may have originally been directed at a tangible hazard (the adventure playground) and attendant anxieties (the moral panic that emerged in the late 1980s about the safety of playgrounds, as chronicled by Ball (2002)) which had made this space then non-standard pub space, and thus a place of focussed concern and careful symbolic management. The sign shown in Figure 5 may therefore represent the ‘root’ meme (Dawkins, 1989: 192) of this now self-perpetuating semiotic rash, for this (long broken) printed sign suggests a more specific and slightly institutional origin than more recent ‘home-made’ article offspring subsequently added alongside it.

This case study story ends with the death of the pub. The successors to the publican rebranded some of the paddock signs, traded for about a year, and then the pub fell silent. No sign announced closure. This was simply communicated by the new negative state of not-being-open. Locked doors, an absence of lights on inside and the empty car park informed former patrons of the pub’s terminal change of state. By 2013, the end of the study period, the pub building had been turned into apartments. The courtyard wall had been raised higher, a sign affixed to the gate signalling that it was now a private space. The painted pub sign remained though, confusing some passers-by about the nature of this place, but perhaps also adding a heritage boost to the ‘branding’ of what was now ‘characterful’ residential real estate.

But, over in the paddock nothing had changed. No new use has been found for this space, and it remained on auto-pilot. The seasons came and went but the increasingly ambiguous signs remained pinned to the fence, still alluding to some inexplicable need for caution within the (now overgrown) field. And thereafter the signs continued to act upon passers-by, deterring entry into the field, acting out a dead-hand legacy effect for as long as their ink resisted erasure by sunlight, their rusting drawing pins held fast against the elements and the rotting fibres of the fence posts retained enough strength to stay upright.

Conclusion

Whilst the circumstances found in a single case cannot be generalised, this study’s value lies in how it presents an alternative way of interpreting owner awkwardness about public access to their green spaces, one that ultimately rests neither on neat assumptions of economic rationality or of a sophisticated liability and risk calculus.

My investigation of the paddock found no manifest, rational motives or meaning-making that could readily explain the owner’s awkward presentation of this field as an ambivalent, simultaneously open and closed public green space. Accordingly, I have presented an interpretation that, whilst still acknowledging some influence for wider context (i.e. the economics of marginal pubs and the prevalence of ‘health & safety’ discourse), has asserted, and foregrounded the power of local lingering, intuitive factors in the formation of place. The case study thus shows how the ambiguity of pub’s beer garden is a product of the site-specific interplay of the attitude- and action-shaping power of habitus (i.e. the self-sustaining place-forming habits of both owners and their premises), the approximate, pragmatic logics of lay legal cognition (i.e. owner’s working assumption about how relevant law and liabilities apply to their sites) and the instabilities of a place’s economic context.

Legal geographers Braverman et al (2013: 28) have acknowledged the importance of incorporating an analysis of ‘habits of territory’ into their field, and that this should be pursued via examination of the pragmatism, and the processual and temporal flux to be found entrained in actual instances of spatial management. Such an approach, they say, would challenge the tendency within scholarship that explores the place-forming interrelations of law and geography to reflexively regard ‘a fence is a manifestation of some larger phenomenon (Property), operating at some higher level’. This study has sought to do just that – to show that this urban green space’s fence and its signage, rather than being a direct pointer either to a campaign of urban enclosure or a deliberative risk management consciousness, may actually be a material and semiotic residue (or surplus) of successive owners’ habit-formed half-thought.

But – as has been shown – even the ambivalent framing of a green space arising from residue, surplus and half-thought can affect the perceived accessibility of a place to public access and use. Therefore, this half-thought effect needs to be taken account of in seeking to understand the effective provision and use of urban green space. Further studies are needed to investigate whether this effect is limited to improvisational, owner-managed premises which are being used for marginal businesses in sectors suffering economic stress and/or fragmentation (like urban-fringe pubs), or whether the presentation of ambiguous, supposedly open but seeming closed, urban green spaces is prevalent across a wider range of business- and premises-types.

Luke Bennett, Reader in Space, Place & Law, Department of the Natural & Built Environment, Sheffield Hallam University, City Campus, Sheffield S1 1WB. Email: l.bennett@shu.ac.uk

Altman, I. (1975) The Environment and Social Behaviour – Privacy, Personal Space, Territory and Crowding. Belmont CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Andrews, N. (2000) The inherited ‘peculiarities of the English’: exploring the culture of the common law statements of directors’ duties with Luhmann and Bourdieu. In: Mads A, and Sugarman D, (eds.) Developments in European Company Law. London: Kluwer: 163-223.

Atkinson, R. and Blandy, S. (2017) Domestic Fortress: Fear and the New Home Front. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Augé, M. (1996) Non-Places. London: Verso. (Translated by John Howe)

Ball, D. (2002) Playgrounds – Risks, Benefits and Choices (Contract Research Report 426). London: Middlesex University for the Health & Safety Executive. Available at: http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/crr_pdf/2002/crr02426.pdf [Accessed: 18/5/18]

Bauman, Z. (2006) Liquid Fear. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bennett, L. (2010) Trees and public liability – who really decides what is reasonably safe? Arboricultural Journal – The International Journal of Urban Forestry, 33, 141-164.

Bennett, L. and Crowe, L. (2008) Landowners’ liability? Is perception of the risk of liability for visitors accidents a barrier to countryside access? Project Report. Sheffield: Countryside Recreation Network. Available at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/678/ [Accessed: 18/5/18]

Bennett, L. and Crawley Jackson, A. (2017) Making common ground with strangers at Furnace Park. Social & Cultural Geography, 18, 1, 92-108. CrossRef link

Bennett, L. and Gibbeson, C. (2010) Perceptions of occupiers’ liability risk by estate managers: a case study of memorial safety in English cemeteries. International Journal of Law in the Built Environment, 2, 1, 76-93. CrossRef link

Berger, P. and Luckmann, T. (1971) The Social Construction of Reality – A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Bottomley, A. and Moore, N. (2007) From walls to membranes: fortress polis and the governance of urban public space in 21st century Britain. Law Critique, 18, 171-206. CrossRef link

Bourdieu, P. (1987) The force of law: toward a sociology of the juridical field. Hastings Law Journal, 38, 805-853 (translated and introduced by Richard Terdiman).

Braverman, I., Blomley, N., Delaney, D. and Kedar, A. (2013) The expanding spaces of law: A timely legal geography. Buffalo Legal Studies Research Article Series, 32, 1-46.

Cohen, S. (2011) Folk Devils and Moral Panics. London: Routledge. CrossRef link

Country Land and Business Association (CLA) (2007) Response to the DEFRA Consultation on Proposals to Improve Access to the English Coast, submission dated 11 September 2007. London: Country Land & Business Association.

Dawkins, R. (1989) The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Delaney, D. (2010) The Spatial, the Legal and the Pragmatics of World-Making – Nomospheric Investigations. Abingdon: Routledge.

Dennis, M. and James, P. (2015) User participation in urban green commons: Exploring the links between access, voluntarism, biodiversity and well being. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 15, 22-31. CrossRef link

Ewick, P. and Silbey, S.S. (1998) The Common Place of Law. London: University of Chicago Press. CrossRef link

Farley, P. and Symonds-Roberts, M. (2011) Edgelands – Journeys into England’s True Wilderness. London: Jonathan Cape.

Forestry Commission (2005) Woodland Owners’ Attitudes to Public Access Provision in South-East England – Information Note. Edinburgh: Forestry Commission.

Gentle, P., Bergstrom, J., Cordell, K. and Teasley, J. (1999) Private landowner attitudes concerning public access for outdoor recreation: cultural and political factors in the United States. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 6, 47-66. CrossRef link

Harvey, D. (2008) The right to the city. New Left Review, 53, 23-40.

Landry, C. (2005) Risk and the creation of liveable cities. In: What Are We Scared Of? The Value of Risk in Designing Public Space. London: CABE Space: 2-11.

Layard, A. (2011) Shopping in the public realm: a law of place. Journal of Law and Society, 37, 412-41. CrossRef link

Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell (Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith).

Low, S.M. (2004) Behind the Gates: Life, Security and the Pursuit of Happiness in Fortress America. Abingdon: Routledge. CrossRef link

Lupton, D. (1999) Risk. London: Routledge.

Minton, A. (2009) Ground Control – Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First Century. London: Penguin.

Mitchell, D. (2003) The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. New York: The Guilford Press.

MMC (Monopoly & Merger’s Commission) (1989) The Supply of Beer, a Report on the Supply of Beer for Retail Sale in the UK, Cmnd. 651. London: HMSO.

Mutch, A. (2000) Trends and tensions in UK public house management. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 19, 361-374. CrossRef link

Mutch, A. (2001) Where do public house managers come from? Some survey evidence. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 13, 86-92. CrossRef link

Mutch, A. (2003) Communities of practice and habitus: a critique. Organization Studies, 24, 383-401. CrossRef link

Northern Ireland Assembly (2013) Access and Liability Briefing. Available at: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/publications/2013/environment/2013.pdf [Accessed: 18/4/18]

Özgüner, H. (2011) Cultural differences in attitudes towards urban parks and green spaces. Landscape Research, 36, 599-620. CrossRef link

Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, A. (2007) Fear in the Lawscape. In: Pribãin J, (ed.) Liquid Society and Its Law. Oxford: Ashgate: 79-100.

Pratten, J.D. (2007a) The development of the modern UK public house, Part 1: the traditional British public house of the twentieth century. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 19, 335-342. CrossRef link

Pratten, J.D. (2007b) The development of the modern UK public house, Part 3: the emergence of the modern public house 1989-2005. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 19, 612-618. CrossRef link

Public Health England (2014) Local Action on Health Inequalities: Improving Access to Green Spaces. London: Public Health England.

Rottenburg, R. (2000) Sitting in a bar. Studies in Cultures, Organizations and Societies, 6, 87-100. CrossRef link

Sack, R. D. (1986) Human Territoriality – Its Theory and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Silbey, S.S. (2005) After legal consciousness. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 1, 323-68. CrossRef link

Teasley, R. J., Bergstrom, J. C., Cordell, H. K., Zarnoch, S. J. and Gentle, P. (1997) The Use of Private Lands in the US for Outdoor Recreation: Results of a Nationwide Survey. Athens, GA: University of Georgia.

Wildavsky, A. and Dake, K. (1990) Theories of risk perception: who fears what and why? Daedalus, 119, 41-60.

Wright, B.A., Kaiser, R.A. and Nicholls, S. (2002) Rural landowner liability for recreational injuries: Myths, perceptions, and realities. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 57, 183-191.