Abstract

Over a quarter of adults in the UK are living with obesity (LwO) (BMI ≥30kg/m²). Weight discriminatory practices are encountered by these individuals at all stages of the employability lifecycle. There is currently no legal protection against obesity discrimination, as obesity is not a protected characteristic (PC). This qualitative synthesis explores the lived experience of obesity in the workplace to understand the impact of weight-related stigma.

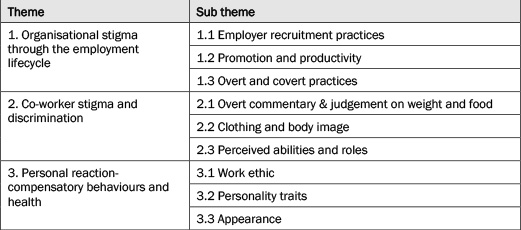

Qualitative studies were compiled through thematic synthesis to identify themes. Eleven studies and grey literature were included. Three overarching themes were identified: (1) Organisational stigma through the employment lifecycle; (2) Co-worker stigma and discrimination; (3) Personal reaction- compensatory behaviours and health.

Stigmatizing attitudes are enacted and embedded across workplaces, in recruitment, operational, promotion and remuneration activities. Discriminatory practices were embedded in workplace culture. Participants reported being treated differently and reacted with compensatory behaviours to moderate the impact on their wellbeing.

Workplace weight-related discrimination impacts the wellbeing of those LwO. Employers need to manage workplace discrimination, ensure unconscious and conscious bias is removed from recruitment, culture and remuneration practices and ensure equality of opportunity. The legal terrain offers little protection and should be reviewed. Establishing obesity as a PC would be instructive in catalysing organisational change.

Introduction

Over 60 per cent of the UK adult population are now living with overweight or obesity with financial, social and health implications for individuals, families and wider society (NHS Digital, 2022). In 2021, 26 per cent of the UK adult population were living with obesity (NHS Digital, 2022). Obesity is more prevalent in lower socioeconomic groups, black and ethnic minority groups and women, highlighting that it is a disease of inequality (NHS Digital, 2022). Individuals with obesity are more likely to be educated to lower levels, in lower paid or more insecure jobs, and receiving lower wages than those of a ‘healthy’ weight (Campbell et al., 2021) which perpetuates the social gradients associated with obesity and of health inequality.

Individuals in the UK are living and working within an ‘obesogenic environment’ which contributes to rates of obesity due to the role of environmental and systemic factors which drive overconsumption of food and drink and encourages sedentary behaviours (Butland et al., 2007). The obesity epidemic is a societal and system-wide issue, within which the role of the workplace should be considered (Sorensen et al., 2016). As such, the management of the obesity crisis requires more than just the individual agency of people living with obesity. Despite this, lack of weight management is traditionally perceived as a failure of the individual who is ‘blamed’ for lack of willpower or laziness, assumptions which have implications for societal perceptions of those living with obesity (Puhl & Heuer, 2010). The system-level embeddedness and acceptance of these negative character and personality traits is increasingly being viewed as synonymous with excess weight which has fuelled an ‘acceptable prejudice’ leading to social exclusion, stigma and bias (Westbury et al., 2023). Literature describes how the stigma of obesity affects individuals in society, education, healthcare and employment and how that has longer-term implications for physical and mental health conditions, educational attainment, earning potential, relationships and quality of life (Brown et al., 2022). Indeed, obesity stigma is not solely a UK-based problem, but a global phenomenon. As such, the recent World Obesity Federation position statement provided nine recommendations with the aim of reducing weight stigma across countries and cultural contexts (Nutter et al., 2024) and a joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity has also been published (Rubino et al., 2020). Despite these recommendations, the societal, policy and practice landscapes remain relatively unchanged. Specifically, across the world, in the twenty-first century, it remains lawful to discriminate against citizens because of their weight (Puhl et al., 2021). However, one multinational empirical-based study published in 2015 suggested widespread support in the USA, Canada, and Australia to prohibit employers from refusing to hire, pay lower wages to, or dismiss workers because of their weight (Puhl et al., 2021).

Whilst this review draws on international evidence, it takes a UK and EU specific narrative as an exemplar of the legislative context. However, there is a paucity of obesity-protective legislation internationally deeming this review equally relevant to an international audience. No legal protection currently exists for citizens living with obesity under UK or EU laws (Brown et al., 2022; Rubino et al., 2020). The UK domestic legal framework encompassing anti-discriminatory practices is defined by the Equality Act (EA) 2010 (Equality Act, 2010). This legislation identifies nine protected characteristics (PC) covering the recruitment, selection, and employment of workers in UK workplace settings. UK law allows employers discretion in the choice of whom to employ, under which terms and conditions and to classify them as full-time, part-time, zero hours and other forms of casualised labour (Bennett et al., 2016). Some elements of the wider debates on anti-discrimination laws may encompass the juxtaposition between advocating for the careers of citizens with disabilities, and yet stereotyping the citizens living with obesity as unfit for work in UK workplace settings.

The EA 2010 specifically defines one PC as disability related discrimination, occurring when a worker has a physical or mental impairment that has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on their ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities, including discrimination in education, work and services provided. Section 6 of EA 2010 provides protection for the categories of age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, race, caste, ethnicity, religion, belief, sex, and sexual orientation. Any disability must fall within this definition of discrimination.

This definition of disability discrimination does not currently extend to people living with obesity (that is, a BMI over 30kg/m²) meaning that under current legislation there is no protection for people who find themselves victims of anti-discriminatory behaviours due to their weight. Such claimants are therefore not entitled to compensation against employers in a UK employment tribunal. However, a leading EU decision (Karltoft v Municipality of Billund: Case C-354/13) ruled that obesity of itself is not a disability, but that obesity may be regarded as a disability if it causes the person some limitation in physical or mental capacity resulting from an impairment which may impact upon their participation in employment. In this specific case, the facts established that the claimant’s obesity which worsened a pre-existing complaint and resulted in a workplace dismissal was disability related discrimination and illegal. Although these circumstances show a potential for obesity related dismissals to be unlawful in workplace settings, it is limited to very specific circumstances and cannot automatically be used as a means of bringing similar claims under the EA 2010.

The arguments voiced against people living with obesity being included as a PC under the EA 2010 show that UK courts interpret ‘disability’ as being limited to conditions which are identified by medical science as ‘disabling’ and impact upon victims’ lifestyles, that is, progressive conditions including cancers. As weight gain and obesity are not ‘progressive’ conditions, the UK law does not accommodate such individuals as being the subject of anti-discriminatory practices, despite calls for strong and clear policies to prohibit weight-based discrimination and the recognition that ‘policies and legislation to promote weight discrimination are an important and timely priority to reduce or eliminate weight-based inequities’ (Rubino et al., 2020; Puhl et al., 2015, pp692). Potentially therefore, UK employers and fellow employees may perpetuate and operate an environment where stigmas reflect anti-obesity views, opinions, and behaviours, yet are not regarded as unlawful.

This review aims to understand the lived experience of adults living with obesity in the workplace and employment settings and identify policy-level changes which would improve the system to address health-related inequality. The findings and conclusions are important because they identify how obesity can limit lifestyle, careers, and access to services in civil society. The lived experience of such citizens is thus a key indicator of where these limitations are encountered in daily life and experience.

The purpose of this paper therefore is to review previously published qualitative data to explore the lived experiences, including discriminatory behaviours, of those living with obesity in workplace settings.

Materials and methods

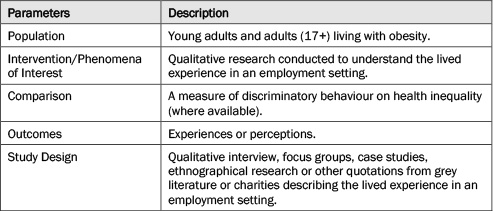

This qualitative thematic synthesis was guided by published principles (Thomas & Harden, 2008). The research question was defined using the PICOS protocol outlined in Table 1.

Search strategy

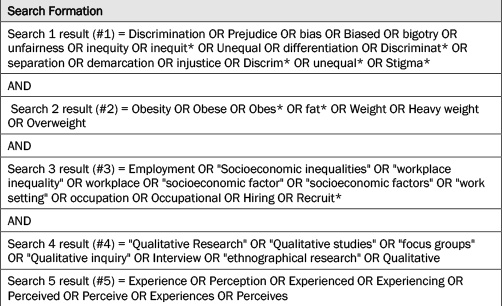

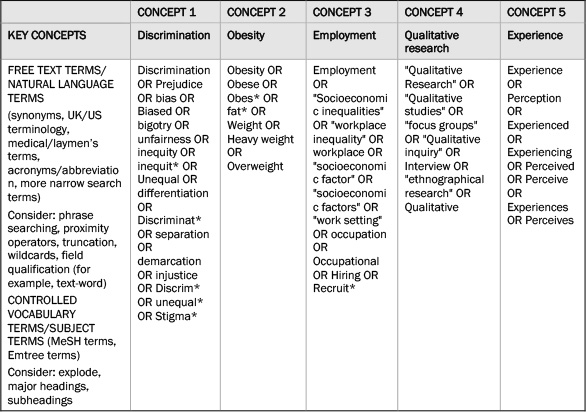

Key words from the description of the PICOS research question parameters were taken as concepts to inform the search strategy. The search strategy combined free text terms and controlled vocabulary terms for obesity, discrimination, employment, qualitative research, and experience as shown in Table 2. The search terms for obesity included overweight. Search terms for employment were taken from a peer reviewed article and modified (Giel et al., 2010). In the work by Giel et al. (2010) the scientific databases PubMed and PsychINFO were searched for potential studies both interesting and eligible for the present review. The search was performed using the key words ‘overweight’, ‘obesity’, ‘weight’, ‘BMI’, ‘work’, ‘occupation’, ‘occupational’, ‘profession’, ‘professional’, ‘employment’, ‘hiring’, ‘bias’, ‘stigma’, ‘stigmatization’, ‘discrimination’, ‘stereotype’, ‘stereotypization’. The keywords related to employment, gaining employment, and workplace were lifted and added as part of the search terms (Table 2). These include ‘occupation’, ‘occupational’, ‘employment’, ‘hiring’. A wild card to assimilate words with the associated terms from the databases and double straight quotation marks common to all databases were used to keep phrases together. These concepts and their search terms were organised into a single string joined by the Boolean operator OR within concepts. The Boolean operator AND was used in combining multiple concepts.

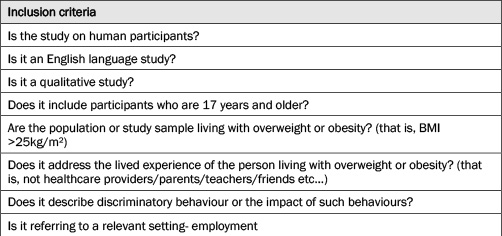

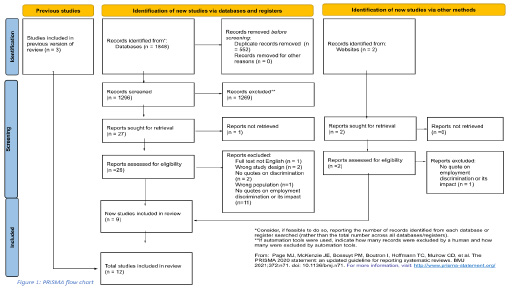

The full search strategy was consistent across databases. Comprehensive searches were conducted on the following online databases and undertaken in July 2022: APA PsycInfo, PubMed: results, MEDLINE ProQuest, MEDLINE EBSCOHOST, Scopus and CINAHL. Duplicates were removed prior to screening in a three-stage process: (1) Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility against inclusion criteria (see Table 3); (2) Available full text were retrieved; (3) A final selection made based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The screening was conducted using the Ryyan tool to organise and track progress of screening (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Additional grey literature including Weight of the World, Obesity Action Coalition (WOW OAC) website (Obesity Action Coalition, 2023) and results from a previous unpublished review on discrimination within the healthcare setting that addressed discrimination in the employment setting were included as additional results for the review. Twelve studies were included in the final synthesis, as seen in the PRISMA statement (2020) (Figure 1).

Quality assessment

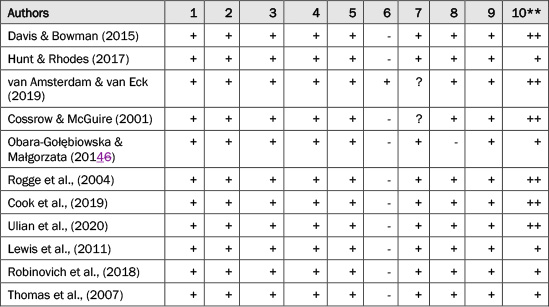

Quality of the individual studies was assessed independently by two researchers using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Study Appraisal Tool (CASP, 2025). Research was not excluded from the synthesis on the basis of quality (Table A.2 in Supplementary Materials). No studies were found to be of low quality.

Data extraction

Extraction of data from the studies was in two phases. A database of included papers was produced that captured detailed information of the population, themes, authors, year of publication, aims, country, data collection method, themes and sponsorship information. Next, the findings of qualitative research- all the text labelled as ‘results’ or ‘findings’ in study reports as well as ‘findings’ in the abstracts following Thomas and Harden’s (2008) description of results for thematic synthesis. All the results of the studies were extracted into a word document. This document was uploaded into QSR’s NVivo software for qualitative data analysis. Video results from WOW OAC (Obesity Action Coalition, 2023) were transcribed from speech to text and uploaded as a Word document to the software package.

Analysis

This thematic synthesis was based on previously published principles (Thomas & Harden, 2008). The researchers followed the process of thematic analysis by Braun & Clarke (2006) which is an iterative process consisting of six steps: (1) Familiarising the research team with the data; (2) Codes were assigned on a line-by-line basis to every applicable finding (IO), resulting in a preliminary 54 free codes; (3) Descriptive themes were generated from the free codes, which began to take on a hierarchical order to group the data; (4) Researchers (LN & JS) reviewed and developed analytical themes by generating new concepts to analyse the themes independent of the original publications (Braun & Clarke, 2006). NVivo (QSR international Pty Ltd, 2017) was used for coding and data analysis. Findings were all quotations reported in the ‘results’ section of studies recorded from employee perspectives; (5) Defining and naming the themes where an inductive verbatim approach was taken, with the objective of generating new theory via a data search to identify relationships that could relate to the research aim. Final themes were deemed complete when they were distinct and internally consistent; (6) Locating exemplars in the text to describe and represent the theme.

Results and discussion

The databases searched returned the following results: APA PsycInfo: 444; PubMed: 209; MEDLINE ProQuest: 638; MEDLINE EBSCOHOST: 229; Scopus: 109 and CINAHL: 219 (see Figure 1).

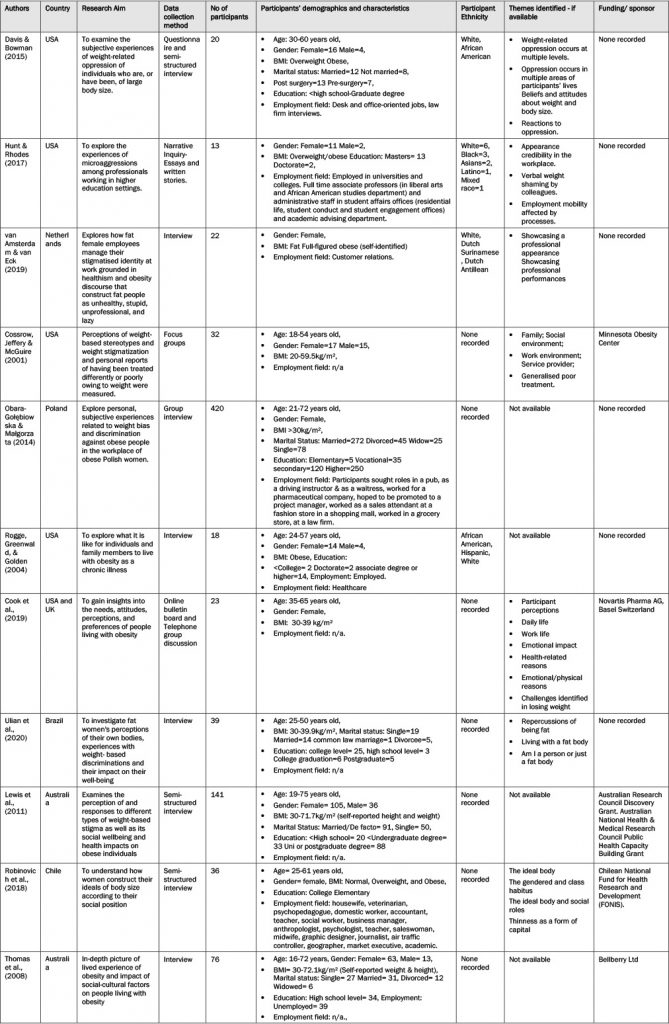

Eleven included papers and a video resource from OAC were identified providing a geographical coverage of North America (n=5), South America (n=2), Europe (n=3), and Australia (n=2). These were published between 2001 and 2020 and included 840 participants. Only two papers highlighted the specific occupation of all the participants, two made no mention of any participant occupation, two stated that 98.4 per cent and 49 per cent of participants each were in employment, whilst others only mentioned the broad industry in which the participant worked. Employment included: customer relations, ranging from unskilled labour to highly skilled labour, desk jobs to physically active and customer facing jobs. See Table 4 for study and participant characteristics. The majority of studies and video data sources (n= 10) focussed on experiences of obesity stigma and discrimination. The studies also explored the impact of stigma and discrimination (n= 2), responses to weight-based stigma (n= 3) and body perception (n= 3). Interviews including semi-structured interviews were the most commonly applied methods for data collection (n= 6).

Thematic synthesis identified three overarching themes which are described below and in more detail in Table 5.

Table 5: Summary of themes and sub-themes

Organisational stigma through the employment lifecycle

Studies incorporating lived experiences suggest that obesity discrimination and stigmatizing behaviours frequently occur in Western societies and environments (Puhl & Heuer, 2010). The workplace provides one such environment where individuals encounter discriminatory practices associated directly with obesity and weight stigmas (Giel et al., 2010). Obesity is unique in that it is highly visible, and so can promote prejudice from potential employers and co-workers who may assume the condition is controllable, yet multiple systemic factors (for example, social background, genetics and income) contribute to the risk of developing obesity (Institute for Employment Studies, 2019). Discriminatory practices and stigmatizing behaviours are encountered by individuals at all stages of the employability life cycle – within recruitment and selection processes, within workplace roles and activities, allowing fewer opportunities for advancement, and often leading to lower, or no, bonuses and other workplace-related rewards (Giel et al., 2010). The cumulative effects of such practices frequently undermine the confidence and life chances of the people living with obesity. The research presented here demonstrates widespread obesity-related stigma and discrimination in many different employment fields. Here we suggest themes and sub-themes from the literature providing a composite analysis of the life challenges, and barriers, to employment opportunities encountered by those living with obesity.

Employer recruitment practices

Yarborough et al.’s (2018) literature review concluded that individuals living with overweight or obesity are less likely to influence organisational decision making than co-workers of ‘normal’ weight (Yarborough et al., 2018). These discriminatory and stigmatizing practices often arise from employer and coworkers’ perceptions about the capability and capacity of individuals viewed as overweight or obese – often manifested in the perpetrator’s own capability and discriminatory prejudices. These discriminatory behaviours are often encountered immediately upon contact with the organisation, specifically its recruitment and selection procedures. This immediate, discriminatory and overt behaviour was recounted by participants from both a self-perceived perspective, and through confirmation of the stigma directly from employers.

Walking through the door and seeing the face and, you know, watching the body language of the person that was the person that interviewed me on the phone, and instantly knowing with the “errs” and the “ahhs” that you know they’ve made a judgment call just by looking at my size. (Davis & Bowman, 2015, p. 276)

These immediacy and overt behaviours were not limited by sector or occupation, extending to large organisations, including those traditionally portraying a customer-oriented profile and focus.

I’ve been for job interviews, and they said you’re not what we’re looking for. When I asked why, they said ‘well your size, we want someone who’s appealing greeting our customers’. (29-year-old female; Thomas et al., 2008, p. 324)

These comments exemplify the extent of overt stigmas and biases towards obese and overweight citizens in workplace settings, prompting the phrase from Bento et al.’s studies (2012 cited in Bajorek and Bevan), that ‘weightism is the new racism’, cautioning that prejudice against those perceived as overweight mirrors societal discrimination based on race over 50 years beforehand. Another example of prejudicial and discriminatory behaviours attributable to the workplace setting is in the example of promotion and productivity.

Promotion and productivity

There is consistent evidence of lack of progression due to obesity (Levay, 2014 cited in Bajorek and Bevan), and also increasing incidence of lower pay, with those living with obesity, on average earning less in the same role as their counterpart workers, in addition to being subjected to the weight stigmatizing behaviours from employers (Puhl & Heuer, 2010). These employer behaviours were notable for prejudices and perceptions about the capacity of overweight citizens. For example:

I’m barred from promotion because of a senior management’s perception that larger people are lazy. (Cook et al., 2019, p. 849)

These reduced employability chances were often determined by their perceived capabilities linked to the prejudices and perceptions of fellow workers who judged the dress and appearance of their colleagues living with obesity.

As you look, you’ll be treated, the way you dress…everything depends on how you look… A fat woman won’t be hired anywhere, and don’t tell me otherwise…at my work, when I… interview people for the December season, I’m told…’please don’t hire any chubby ones because they are less agile.’ Fatness is associated with… that the person is silly, slow, has no initiative and is not fast… It’s bad what I’m going to tell you, but a chubby woman is associated with low class…or they say, ‘that fat ugly woman’ or ‘that fat woman who has no education’… (Daniela; Robinovich et al., 2018, p. 85)

Individuals perceived as overweight or obese by potential employers are therefore sometimes categorised as less productive, not seen as team players, and, consequently, often overlooked for promotion and management roles, thereby impacting upon the person’s financial security as a result.

The financial impact is trying to ensure that my employer is happy with [me] taking time off from work, and also the feeling that I’m barred from promotion because of senior management’s perception that larger people are lazy. (Cook et al., 2019, p. 849)

Such attitudes may be perpetuated by studies (Goettler et al., 2017) suggesting that individuals living with obesity and overweight cost their employers more from short term absences than their ‘normal’ weight counterparts. Such stigmatizing behaviours and covert discrimination extend to ‘front of house’ responsibility, therefore leaving individuals often excluded from strategic and critical operational roles which are likely to be within their knowledge, experience and capacity.

I work for a pharmaceutical company. I was hoping to be promoted to project manager. I lost my promotion to a slim friend who was identically qualified but had two years less professional experience than me. (Obara-Golebiowska, 2014, p. 150)

Clearly, the participants’ experiences of a lack of access to promotion and progression in workplace settings is a common experience for those perceived as overweight and obese by fellow citizens. Such experiences might be attributed to ingrained prejudices and behaviours that shape some employers’ own learned, or perhaps copied, responses to the overweight and obese employee and worker.

Overt and covert practices

Where the participants reported being rejected for a job that they were already qualified for, then the prejudicial and discriminatory behaviours were both overt and direct, sometimes linked to gender and notions of perceived physical attractiveness.

I was trying to get a job as a driving instructor. I had several years of experience and the required qualifications. The employer who was the owner of the driving school checked my qualifications, then he looked me over and said that they preferred male instructors. He said that they employed women only if they were ‘hot babes who attracted customers’. He also joked that ‘the suspension won’t last long with your weight’. (Obara-Golebiowska, 2014, p. 150)

This comment re-iterates practices of (1) weight stigmatization, and (2) overt sexism, the latter being illegal, and showing the employer’s ill-disguised contempt for anti-discriminatory laws and the possible sanctions that may follow from its breach.

One participant highlighted that employers were neither candid nor truthful about vacancies, choosing other candidates based upon the employers’ specific prejudices. The reasons for rejecting the applicant were not clearly articulated to them, only becoming apparent later, employers were therefore perceived to avoid responsibility by inventing specious excuses, covertly hiding the real reasons for their rejection of the applicant.

I was looking for work at university, and I called about a job in a pub. I was invited to an interview, but when the manager saw me, he said that they had already found someone and cut me short. A few days later, my slim friend from the dorm went to the same pub because the ad was still up there, and she got the job. (Obara-Golebiowska, 2014, p. 150)

These examples confirm that discriminatory practices embed barriers to social mobility towards citizens living with obesity and overweight. Significantly, the prevalence of discriminatory practices in workplace settings is not limited by culture or geography, as studies reflect similar experiences of those living with overweight in many alternate jurisdictions and geographical settings (Rubino et al., 2020). Consequently, the life and employment experiences of participants were impacted by a lack of access to career progression, in-work promotion and adequate remuneration from employment.

Co-worker stigma and discrimination

This theme describes the ways in which people living with obesity felt judged and stigmatised by their fellow colleagues and co-workers. Discriminatory behaviours from co-workers were often embedded within the workplace culture and were a ‘normalised’ form of stigma.

Overt commentary and judgement on weight and food

Participants report that their co-workers often openly commented on their appearance which consolidated feelings of being treated differently, with comments aligning to stereotypical traits associated with overweight and obesity. These comments often also commonly amalgamated racial stereotypes with comments directly related to their weight or eating habits:

I thought Asians are supposed to eat slow and precise, but then again you are tall and fat, so you beat the odds. (Hunt & Rhodes, 2017, p. 28)

As such, these comments affected the social relationships that were built at work and involuntary exclusion from activities with colleagues inside and outside of the workplace, consolidating the feeling of being ‘different’ and removing autonomy and decision-making from the person living with obesity.

Up to a certain point, I always thought that I had good relations with other people in the office. One day, a colleague told me that all employees had been going on regular outings to the spa for several months. I was never invited. My colleague tried to explain that they had never invited me because I would probably feel uncomfortable in a spa. (Obara-Golebiowska, 2014, p. 150)

There was also open commentary and judgement about the food being consumed in the workplace, and a lack of support for attempts to change dietary habits to promote weight loss which prevented those living with obesity from socialising with other co-workers over breaks and meal occasions.

I am too embarrassed to eat with other people at work. On several occasions, a female colleague remarked in front of the others that I shouldn’t eat too much. (Obara-Golebiowska, 2014, p. 151)

This commentary on food and eating behaviours led to a greater level of exclusion and discomfort at work and reduced social interactions with co-workers.

Clothing and body image

Participants reported that clothing was also a conversation and commentary topic for colleagues who discussed and mocked their outfits in a very open and discriminatory way leading to feelings of anguish and being different from their colleagues. It also led to commentary about their body shape and size.

One day I wore a new outfit in the office and the admin turned around, looked at me, pointed, and started laughing. Then she calls out, loudly, “did you see what (my name) is wearing today? Come look!” Inviting others in the office to come and laugh at me. Thankfully no one else joined in, but no one stood up for me either. (Hunt & Rhodes, 2017: p28)

As obesity discrimination in the workplace appeared to be commonplace and acceptable, other discriminatory practices (for example, racial and sexual remarks) were also embedded into comments or combined with fat-shaming comments such as one participant who had received the following comment from a co-worker, ‘I bet you’re hiding some curves under that long dress.’ (Hunt & Rhodes, 2017, p. 27).

There were also back-handed comments about weight and clothing such as a fellow co-worker who had lost weight and had some ‘hand me down’ clothing to give to colleagues who he perceived to be heavier than him, and a lack of comments that were noted about people looking nice or receiving positive affirmations relating to their clothing.

Perceived abilities and roles

The shape and size of participants was perceived to be an indicator of their seniority, ability, skillset and intellect by others with a perceived feeling of judgment that people who earn well should be able to look after themselves.

There seems to be a general consensus until coworkers…get to know me, that I am dumb, lazy, dishonest, lying, because after talking to some of them after they’ve gotten to know me, [they’ve] actually told me that they never figured that “somebody with your actual body weight could actually know what they were doing.” Because if you were that smart you wouldn’t be that heavy or that fat…I’ve definitely had to [fight for respect], making it known, especially to the nursing staff, that I do know what I am doing…It has been almost two years, and it’s taken every bit of that time. So, you have to get past the first impressions, the prejudice. (Rogge et al., 2004, p.311)

Paradoxically, colleagues also felt that their co-workers’ weight was detrimental to the business as overweight colleagues were less likely to accrue new clients or additional business, with the underlying logic that their weight was negatively associated with expertise and productivity.

I work in a law firm. I once overheard my colleagues talk about me. One of them said that I would have more clients if I lost weight. (Obara-Golebiowska, 2014, p. 151)

Sadly, the organisational context which allows these discriminatory behaviours without challenge or disciplinary procedures develops a workplace culture whereby open obesity discrimination becomes a learnt behaviour, and stigmas against overweight and obese persons may be absorbed into the workplace culture. Therefore, a person living with obesity is left to accept discriminatory behaviours as workplace norms (often reflected in wider society) which becomes an accepted (and expected) institutionalised form of bias embedded in the organisational levels. However, it is well evidenced that acceptance of, and regular exposure to, these stigmatising, isolating and degrading prejudices has long term physical and mental health consequences for individuals living with obesity and can lead to loss of productivity, absenteeism, loneliness and so on (Puhl & Heuer, 2010; Giel et al., 2010), which may in fact perpetuate the stereotypes around laziness and perceived capability.

Personal reaction – compensatory behaviours and health

Many of the participants discussed how they had overcome some of the discriminatory behaviours and stigma that they experienced by incorporating compensatory behaviours which changed the way they behaved in their workplace environment as a way of protecting or proving themselves. These compensatory behaviours were in numerous domains including work ethic, physical exertion, personality traits and appearance.

Work ethic

Participants reported an awareness of ‘laziness’ as a common stereotype associated with overweight and obesity. As such, they compensated by demonstrating an over-zealous work ethic (that is, working longer hours, taking less sick leave or time off) which was above and beyond the requirements of their contract to prove their worth to the organisation and colleagues, and counteract the obesity stereotypes.

I’ve never taken time off work because of my weight, but it does impact upon my job. For instance, we have to sometimes physically manage the young people we work with, and this can be exhausting for someone with good stamina and a healthy body. For me it can leave me shaking and unable to move for some time after because of the exertion. (Cook et al., 2019, p. 849)

These types of behaviours are known to be conducive to poor health and participants are more likely to develop work-related ‘burnout syndrome’ (Armenta-Hernández et al., 2021; de Souza E Silva et al., 2023). Burnout syndrome caused by occupational stressors leads to absenteeism and reduced productivity within the organisation which has an impact on individuals, employers and wider society.

Personality traits

Lay people often stereotypically associate fatness with jolliness, with researchers in the 1970s suggesting a ‘jolly-fat’ hypothesis, that is, that people living with obesity are jollier due to obesity protecting against depression (for example, Crisp & McGuiness, 1976), which was later disproved. Participants reported feeling pressure to act in a way that was unnatural to them to comply with this ‘jolly-fat’ stereotype and in doing so, were protecting themselves against less hurtful or detrimental comments (Jansen et al., 2008).

I feel like I have to be a more enjoyable person than others, and funnier. Sometimes I mock myself, only to prevent others from doing that. It is better to make the jokes myself, because then it is less hurtful. People always say I’m funny. And yes, I believe I use humour to compensate for being fat. (Sophie; van Amsterdam & van Eck, 2019, p. 52)

However, it is now well-established that obesity does not protect against depression and those living with obesity are more likely to receive a clinical diagnosis of depression than their healthy weight counterparts (Jansen et al., 2008). There is literature which describes the detrimental effects of ‘masking’ from other health fields. Masking relates to general social practices (such as identity management) and is often driven by stigma avoidance (Miller et al., 2021). Masking in the context of obesity could be applied to this reported pretence of being ‘jolly’, ‘funny’ or more ‘enjoyable’ as a way of coping with or counteracting the stigma associated with obesity. Masking has been described by those living with autism as, ‘a huge emotional and physical toll’ which is ‘exhausting’ (Miller et al., 2021). It is likely that masking could therefore have a similar negative health impact on those living with obesity.

Appearance

Participants reported that many stereotypical judgements in the workplace were due to their appearance and clothing. They reported compensatory practices to select ‘neat, presentable’ clothing and workwear and appear ‘well groomed’, explaining, that they have to put in more ‘effort’.

I noticed that clothes play an important role. I am very much focused on being neat, without any blemishes, no jeans and not something tight. (van Amsterdam & van Eck, 2019, p. 50)

They also reported how official job titles were purposefully displayed more visibly to ensure that people recognised their status or capabilities within the workplace, to counteract perceptions of being lazy or stupid due to their weight.

Well, I wear my badge in such a way that it is very visible. Like, here is my title, so I am not one of those fat lazy persons […] It shouldn’t be necessary, but by showing my titles people see immediately that I am not stupid. (van Amsterdam & van Eck, 2019: p52)

The additional pressures and effort required to consider and enact these compensatory behaviours is significant, and an important factor when considering the burden of living with obesity.

Despite a full search of international databases, there was a paucity of UK and EU-specific evidence in the literature suggesting that further research may be required in this area.

The three overarching themes: Organisational stigma through the employment lifecycle; Co-worker stigma and discrimination; and Personal reaction-compensatory behaviours and health, show the continuous cycles of stigmatizing and prejudicial behaviours that can dominate workplace settings and social discourse in the UK and beyond. These stigmatizing and prejudicial behaviours perpetrated by one (or more) citizens upon another do not arise by chance. They are chosen by the perpetrators, becoming learned or accepted practices that undermine the victims, exposing them to discrimination, and sometimes rejections both professionally and amongst peer groups. These prejudicial behaviours, whilst not overtly illegal per se, operate in workplace settings and elsewhere in society because they are often not challenged or subjected to legal sanctions. The victims of these behaviours are currently not allowed under the UK EA 2010 to progress legal claims for direct or indirect discriminatory activities by reason of obesity alone. Until there are significant changes to the legal position and also the protected characteristics under the EA 2010 in the UK, then these prejudices will prevail, and the victims will continue to endure discrimination and systems ostracising them from society and opportunities seemingly open to other citizens in those same societies. There is a duty upon all of us to re-educate, re-train, and adopt more systems and processes that accommodate ‘difference’ in body weight and shape and understand the needs and feelings of victims. The authors of this paper fully support the recommendations from Rubino et al. (2020) and Nutter at al. (2024) to make global changes to reduce obesity stigma, but feel that the employment context should be explicitly recognised in addition to education, healthcare, or public-policy sectors. These changes can be promoted by legal protection under a revised EA 2010, but this must be alongside workplaces and society making changes that project positive cultures and attitudes towards those who are living with overweight or obesity.

Conclusion

The review demonstrates that overt and covert stigma and organisational bias is prevalent in the workplace and manifests in a multitude of ways from limited uniform sizing, unsolicited dietary advice, and fewer promotional opportunities.

As no legal protection currently exists for citizens living with obesity under UK or EU laws, discriminatory practices continue across employment settings. Whilst discrimination due to body characteristics, specifically obesity, is not recognised by law, instances of obesity stigma and the behavioural prejudices towards those perceived to be obese are commonplace (Rogge et al., 2004). The stigma adds to feelings of inferiority compared to other citizens, or diminished opinions about body shape which are frequently accentuated in workplace settings (Guardabassi & Tomasetto, 2008; Ulian et al., 2020). These factors play into limiting the life chances of citizens who, but for the recognition of obesity as a disabling characteristic, would be able to seek and maintain employment under the protection of the law.

In response, employees living with obesity have adopted compensatory behaviours to ‘prove their worth’ or equivalence to healthy weight colleagues. Obesity discrimination needs to be regarded as socially unacceptable, as with other stigmatised groups (for example, trans groups) and become embedded as a social discourse and debate to promote change in legal, political and social practices. Obesity needs to be recognised as the unwelcome outcome of a system-wide failure, as opposed to an individual problem, which requires a social, system-wide response. In the workplace, this may involve removing barriers to access for individuals living with obesity to ensure they can function in the same way as a healthy weight counterpart, and have the same opportunities available to them, with stricter regulation around weight discriminatory practices at individual and organisational levels.

Organizational cultures can be changed with laws focussed upon individual rights. For example, there have been suggestions that UK law could encompass a statutory definition of bullying and harassment which could include adjacent rights not to be subjected to prejudice and discrimination based on weight bias and stigma (Stander, 2024). Bold interventions are needed to change societal prejudice against those LwO – for example, those enacted for the city of Reykjavik which identified body weight as one protected characteristic within its human rights code (Puhl et al., 2021).

To embed such a mindset shift, the removal of obesity discrimination needs to become important to organisations. Therefore, establishing obesity as a protected characteristic would be instructive in catalysing organisational and behavioural change. Obesity stigmas need to be confronted and resisted.

Appendices

* Questions:

- Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

- Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

- Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

- Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

- Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

- Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

- Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

- Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

- Is there a clear statement of findings?

- How valuable is the research?**

* Yes=+, Can’t tell=? No=-

**Very valuable=++, valuable=+

Lucie Nield, Sheffield Centre for Health and Related Research (SCHARR), Division of Population Health, School of Medicine and Population Health, Regent Court, 30 Regent Street, Sheffield, S1 4DA. Email: l.nield@sheffield.ac.uk

Armenta-Hernández, O., Maldonado-Macías, A., Serrano-Rosa, M. Á, Baez-Lopez, Y. A., Balderrama-Armendariz, C. O., & Camacho-Alamilla, M. (2021). The Relationship Between the Burnout Syndrome Dimensions and Body Mass Index as a Moderator Variable on Obese Managers in the Mexican Maquiladora Industry. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(12), 540426. CrossRef link

Bento R,F., White L.,F., and Zaur S.,R. (2012) “The Stigma of Obesity and discrimination in performance appraisal: a theoretical model”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol.23, pp.3196-3124 cited in Bajorek, Z .and Bevan S. (2019), “Obesity and work: Challenging Stigma and discrimination”, Institute of Employment Studies, Brighton, UK (at p16). CrossRef link

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. CrossRef link

Brown, A., Flint, S. W., & Batterham, R. L. (2022). Pervasiveness, impact and implications of weight stigma. EClinicalMedicine, 47, 101408. CrossRef link

Butland, B., Jebb, S., Kopelman, P., McPherson, K., Thomas, S., Mardell, J., & Parry, V. (2007). Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – Project Report. Foresight. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287937/07-1184x-tackling-obesities-future-choices-report.pdf

Campbell, D. D., Green, M., Davies, N., Demou, E., Ward, J., Howe, L. D., Harrison, S., Johnston, K. J. A., Strawbridge, R. J., Popham, F., Smith, D. J., Munafò, M. R., & Katikireddi, S. V. (2021). Effects of increased body mass index on employment status: a Mendelian randomisation study. International Journal of Obesity, 45(8), 1790-1801. CrossRef link

Cook, N., Tripathi, P., Weiss, O., Walda, S., George, A., & Bushell, A. (2019). Patient Needs, Perceptions, and Attitudinal Drivers Associated with Obesity: A Qualitative Online Bulletin Board Study. Adv Ther. 36, 842-857. CrossRef link

Cossrow, N., Jeffery, R., & McGuire, M. (2001). Understanding Weight Stigmatization: A Focus Group Study. Journal of Nutrition Education, 33(4), 208-214. CrossRef link

Crisp, A. H., & McGuiness, B. (1976). Jolly fat: relation between obesity and psychoneurosis in general population. British Medical Journal, 1(6000), 7-9. CrossRef link

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (2025). Critical Appraisal Checklists. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Davis, H. A., & Bowman, S. L. (2015). Examining experiences of weight-related oppression in a bariatric sample: A qualitative exploration. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 1(3), 271-286. CrossRef link

de Souza E Silva, D., das Merces, M. C., Lua, I., Coelho, J., Santana, A., Reis, D. A., Barbosa, C., & D’Oliveira Júnior, A. (2023). Association between burnout syndrome and obesity: A cross-sectional population-based study. Arch Environ Occup Health. 74(3), 991-1000. CrossRef link

Giel, K. E., Thiel, A., Teufel, M., Mayer, J., & Zipfel, S. (2010). Weight Bias in Work Settings – a Qualitative Review. Obesity Facts, 3(1), 33-40. CrossRef link

Goettler, A., Grosse, A., & Sonntag, D. (2017). Productivity loss due to overweight and obesity: a systematic review of indirect costs. BMJ Open, 7(10), e014632-014632. CrossRef link

Guardabassi, V., & Tomasetto, C. (2018). Does weight stigma reduce working memory? Evidence of stereotype threat susceptibility in adults with obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 42(8), 1500-1507. CrossRef link

Hunt, A. N., & Rhodes, T. (2017). Fat pedagogy and microaggressions: Experiences of professionals working in higher education settings. Fat Studies, 7(1), 21-32. CrossRef link

Institute for Employment Studies (2019, May 16). Obesity and Work: Challenging stigma and discrimination [Press release]. https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/news/obesity-and-work-challenging-stigma-and-discrimination

Jansen, A., Havermans, R., Nederkoorn, C., & Roefs, A. (2008). Jolly fat or sad fat?: Subtyping non-eating disordered overweight and obesity along an affect dimension. Appetite, 51(3), 635-640. CrossRef link

Levay, C. (2014). “Obesity in organisational context”, Human Relations, Vol.67, pp. 565-585. cited in Bajorek, Z. And Bevan S., (2019), “Obesity and work: Challenging Stigma and discrimination”, Institute of Employment Studies, Brighton, UK ( at p.14). CrossRef link

Lewis, S, Thomas, S, Blood, R., Castle, D. J., Hyde, J., & Komesaroff, P. A.(2011). How do obese individuals perceive and respond to the different types of obesity stigma that they encounter in their daily lives? A qualitative study. Social Science and Medicine, 73(9), 1349-1356. CrossRef link

Miller, D., Rees, J., & Pearson, A. (2021). “Masking Is Life”: Experiences of Masking in Autistic and Nonautistic Adults. Autism in Adulthood: Challenges and Management, 3(4), 330-338. CrossRef link

NHS Digital (2022). Health Survey for England, 2021 part 1. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2021/overweight-and-obesity-in-adults

Nutter, S., Eggerichs, L.A., Nagpal, T.S., Salas, X.R., Chea, C.C., Saiful, S., Ralston, J., Barata-Cavalcanti, O., Batz, C., Baur, L.A., Birney, S., Byrant, S., Buse, K., Cardel, M.I., Chugh, A., Cuevas, A., Farmer, M., Ibrahim, A., Kataria, I., … Yusop, A. (2024) Changing the global obesity narrative to recognize and reduce weight stigma: A position statement from the World Obesity Federation. Obesity Reviews, 25(1):e13642. CrossRef link

Obara-Golebiowska, M., & Przybylowicz, K. E. (2014). Employment discrimination against obese women in Poland: A focus study involving patients of an obesity management clinic. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 43(5), 689-690. https://hallam.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/employment-discrimination-against-obese-women/docview/1537949012/se-2

Obesity Action Coalition (2023). View our Video Library. Weight of the World. https://www.weightoftheworld.com/library/

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1). CrossRef link

Puhl, R. M., & Heuer, C. A. (2010). Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 100(6), 1019-1028. CrossRef link

Puhl, R, M., Lessard, L,M., Pearl, R., Grupski, A., & Foster, G. (2021). Policies to address weight discrimination and bullying: Perspectives of adults engaged in weight management from nations. Obesity, 29(11), 1787-1798. CrossRef link

Robinovich, J., Ossa, X., Baeza, B., Krumeich, A., & van der Borne, B. (2018). Embodiment of social roles and thinness as a form of capital: A qualitative approach towards understanding female obesity disparities in Chile. Social Science and Medicine, 201, 80-86. CrossRef link

Rogge, M.M., Greenwald, M., & Golden, A. (2004). Obesity, Stigma, and Civilised Oppression. Advances in Nursing Science, 27(4), 301-305. CrossRef link

Rubino, F., Puhl, R.M., Cummings, D.E., Eckel, R.H., Ryan, D.H., Mechanick, J.I., Nadglowski, J., Ramos Salas, X., Schauer, P.R., Twenefour, D., Apovian, C.M., Aronne, L.J., Batterham, R.L., Berthoud, H.R., Boza, C., Busetto, L., Dicker, D., De Groot, M., Eisenberg, D., … McIver, L., Mingrone G, Nece P, Reid TJ, Rogers AM, Rosenbaum M, Seeley RJ, Torres AJ, Dixon JB. (2020). Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat Med. 26(4):485-497. CrossRef link

Sorensen, G., McLellan, D. L., Sabbath, E. L., Dennerlein, J. T., Nagler, E. M., Hurtado, D. A., Pronk, N. P., & Wagner, G. R. (2016). Integrating worksite health protection and health promotion: A conceptual model for intervention and research. Preventive Medicine, 91, 188-196. CrossRef link

Stander, D. (2024, January 24). Is it time for obesity to become a protected characteristic? People Management, CIPD, London.

Thomas, S. L., Hyde, J., Karunaratne, A., Herbert, D., & Komesaroff, P. A. (2008). Being ‘fat’ in today’s world: a qualitative study of the lived experiences of people with obesity in Australia. Health expectations: an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 11(4), 321–330. CrossRef link

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. CrossRef link

Ulian, M., de Morais Sato, P., Pinto, A., Benatti, F. B., Lopes de Campos-Ferraz, P., Coelho, D., Roble, O. J., Sabatini, F., Perez, I., Aburad, L., Vessoni, A., Fernandez Unsain, R., Gualano, B., & Scagliusi, F. B. (2020). “It is over there, next to that fat lady”: a qualitative study of fat women’s own body perceptions and weight-related discriminations. Saúde e Sociedade. CrossRef link

Van Amsterdam, N., & van Eck, D. (2019). “I have to go the extra mile”. How fat female employees manage their stigmatized identity at work. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 35(1), 46-55. CrossRef link

Westbury, S., Oyebode, O., van Rens, T., & Barber, T. M. (2023). Obesity Stigma: Causes, Consequences, and Potential Solutions. Current Obesity Reports, 12(1), 10-23. CrossRef link

Yarborough, C. M. I.,II., Brethauer, S., Burton, W. N., Fabius, R. J., Hymel, P., Kothari, S., Kushner, R. F., Morton, J. M., Mueller, K., Pronk, N. P., Roslin, M. S., Sarwer, D. B., Svazas, B., Harris, J. S., Ash, G. I., Stark, J. T., Dreger, M., & Ording, J. (2018). Obesity in the Workplace: Impact, Outcomes, and Recommendations. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(1). CrossRef link