Abstract

Reduced availability of, and access to, affordable accommodation coupled with housing benefit reductions, particularly for single people under the age of 35, make it inevitable that more people will require shared accommodation as a financially viable solution to their housing needs. However, there is a reluctance to enter into sharing, particularly with ‘strangers’, and many members of vulnerable groups face challenges such as living with others, gaining access to the private rented sector, and sustaining tenancies. In response to these challenges, the Sharing Solutions Programme, run by Crisis and funded by the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), recently piloted, developed and promoted new models for establishing successful sharing arrangements for single people in housing need. This paper draws on findings from an evaluation of that programme, alongside the literature on shared accommodation, to identify a number of potential barriers to making shared accommodation work, and ways in which these may be overcome. A range of factors are identified as pivotal in the success of sharing in the private rented sector, including changing perceptions of sharing, managing shared properties and supporting tenants. While the paper concludes that sharing can be a viable option for some, it simultaneously recognises the significant resources required to make it successful for tenants.

Introduction

The proportion of households in England living in the private rented sector (PRS) nearly doubled from just over ten per cent in 2003/4 to 19 per cent in 2013/14. Among households aged between 25 and 34 the proportion living in the PRS increased from 21 per cent to 48 per cent during this period (DCLG, 2015: para 2.14). For tenants who are supported by Housing Benefit (HB), the availability and quality of accommodation in the PRS has been problematic, and shared accommodation is scarce. While regulation of Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMOs) and other measures to improve standards have been implemented, one unintended consequence of this intervention has been to reduce the number of landlords willing to negotiate these standards and provide shared accommodation.

The issue of availability has further intensified due to changes in the Local Housing Allowance (LHA) system of Housing Benefit in the PRS (with effect from January 2012) which have reduced the amount of HB available to claimants; and amended the rules relating to the Shared Accommodation Rate (SAR) of LHA, extending it from the under-25s to under-35 year old claimants. This is likely to both increase the demand for shared accommodation and confront individuals from an older age cohort with the often difficult prospect of sharing. At the same time, the PRS is increasingly being relied upon to address the housing needs of homeless people, as the social rented sector contracts, and the Localism Act 2011 gave local authorities (LAs) the right to discharge their homelessness duty into the PRS, close waiting lists and prioritise allocations to people in work.

This paper aims to identify a number of potential barriers to making shared accommodation work and ways in which these may be overcome. It draws on a review of the literature on shared accommodation and findings from an evaluation of the Sharing Solutions Programme (Batty et al., 2015) – a programme run by Crisis and funded by DCLG, to pilot, develop and promote new models for establishing successful sharing arrangements for single people in housing need. A range of cross-cutting factors are identified as pivotal in the success of sharing in the private rented sector, including changing perceptions of sharing, managing shared properties and supporting tenants. The specific successes and challenges of each sharing ‘model’ are set out in more detail in Batty et al. (2015). While it is not within the remit of this paper to lay these out in depth, we discuss the contextual factors within which each model operated.

Sharing in the private rented sector: a suitable housing option for under 35s?

Little research, to date, has focused on sharing amongst young people, especially for low-income and vulnerable groups. A significant part of this body of work is preoccupied with sharing either as an exercise of choice by relatively affluent single young people or ‘young professionals’ (Kenyon, 2000; Heath and Kenyon, 2001; Kenyon and Heath, 2001), or as a temporary stage in the housing pathways of students (Kenyon, 1999). With a few exceptions (Kemp and Rugg, 1998; Rugg et al., 2011; Kemp, 2011; Unison, 2014), relatively little research has focused on young people with low incomes within the PRS who are forced to share, a cohort that has grown recently due to the Shared Accommodation Rate’s extension to under-35s, increasing housing costs and scarcity of accommodation in some locations. The following literature review explores the key themes and issues for younger people on low incomes faced with sharing accommodation: restricted choice; health and well-being; family relationships and parenting; vulnerability; housing management difficulties; and insecurity.

Restricted choice

Kemp (2011) emphasises the difference between the two main groups of sharers – students/young professionals and low-income tenants – in terms of choice and constraint. Focusing on the routes into shared accommodation for the latter group, Rugg et al. (2011) found that a lack of choice about where to live was a common thread that drew respondents together. Choice was limited because of the lack of shared accommodation – and geographical variations were evident in this, with more affordable areas of London attracting more competition – and this was narrowed down even further by ‘the fact that any available property might present a shared arrangement that is simply not suitable’ (Rugg et al., 2011: 11), and compounded by additional fees charged by many letting agencies.

The ‘lived experience’ of shared accommodation is likely to be different for both students/young professionals and low-income sharers: ‘sharing a flat or house with friends or other young professionals is often very different from living with strangers in a dingy HMO at the bottom end of the private rented sector’ (Kemp, 2011: 1025). This point is raised by Rugg et al. (2011) who make a distinction between ‘stranger shares’ – sharing a property with people who were unknown to each other at the start of the tenancy – and ‘friendly shares’ – where two or more friends or acquaintances share accommodation. As long as it was a ‘friendly share’, many young people related that they preferred sharing to living alone as it provided companionship, and a way to economise on rent and living costs (Kemp and Rugg, 1998). Tenants were more likely to experience difficulties with shared accommodation where occupying a ‘stranger share’. This finding was echoed in a study by Kemp and Rugg (1998) in which younger people preferred sharing with friends as opposed to renting a room in a large house with strangers, and often experienced feelings of loneliness and insecurity in this latter situation. In both studies, tenants only opted for sharing or experienced it as positive when it was through choice. In terms of SAR, then, it was crucial to explore whether the top-down constraint of having to rent a room in a shared property had a bearing on tenants’ feelings towards that accommodation.

Young people on SAR are constrained in the choice of supply of suitable accommodation, especially since they are in competition with other, more affluent or (perceived) favourable groups of sharers such as students and young professionals. A study by Clapham et al. (2014) of the housing pathways of young people found that some had tried to access affordable shared accommodation but reported that it was solely for student use. Research by Crisis (2014) found that less than two per cent of rooms in shared houses were available as well as affordable to those on SAR, and an earlier study by Crisis (2012) found that out of the 4,360 rooms advertised on Gumtree and Spareroom.com, only 13 per cent were priced within the SAR and just 66 (or 1.5 per cent of) rooms had landlords who were willing to rent to people receiving benefits. As well as the lack of physical stock, landlords are increasingly unwilling to let their accommodation to under-35s on SAR (Unison, 2014). The LHA evaluation by Beatty et al. (2014) found that, in certain areas, landlords were reluctant to rent shared accommodation due to the perceived management challenges it presented, and were turning away single under-35 year olds due to experiences with previous tenants who could not keep up with their rent payments, or were unable to rent out shared accommodation due to planning restrictions designed to limit the number of HMOs in the local authority area.

Health and well-being

The relationship between health/well-being and housing is well documented in the literature (Page, 2002; Evans et al., 2003). The Department of Health (2011) identified suitable housing as a key component for mental health, citing factors such as overcrowding, room size, and high-rise buildings as impacting on the mental health of residents. Although previous research has highlighted the relationship between HMOs and poor mental health – noting that HMO residents are eight times more likely than the general population to suffer from mental health problems (Shaw et al., 1998) – there is a lack of robust research specifically on how living in shared accommodation as a result of SAR impacts on tenants’ health and well-being. Both HMOs and shared accommodation in the SAR category pose similar challenges for residents. Barratt (2011) found that HMOs may pose a greater threat to the mental health of residents because of greater insecurity, less control, and poorer social networks, and it is likely that this link exists in other types of shared accommodation. In fact, research by Rugg et al. (2011) highlighted particular tenants’ concerns about the environment of shared accommodation around noise and cleanliness of communal areas – factors that may have a detrimental effect on well-being.

Several studies report on the poor quality of the existing stock of shared accommodation in LHA markets, with landlords unlikely to see the financial benefits of investing more in shared accommodation for under-35s (Unison, 2014). The Work and Pensions Select Committee report (2014) includes a statement by St. Mungo’s, which affirms that the majority of PRS accommodation available to those in the SAR group is near the ‘lower limit’ of minimal standards of accommodation. Physical standards are a concern in the PRS as a whole – with 37 per cent of properties classified as ‘non-decent’ (Crisis, 2014) – so those on SAR face an even more restricted choice (Unison, 2014).

Family relationships and parenting

Due to the nature of shared accommodation, a recurrent theme in the literature is the difficulty of maintaining relationships with family members, especially for fathers with non-resident children. Unison (2014) refers to the poor quality of shared accommodation and how the nature of sharing with strangers puts visiting children at risk. A lack of privacy in shared accommodation impinges on the time parents can spend with non-resident children, and ‘may prevent parents from building close intimate relationships with their children’ (Barratt et al., 2012). The same study by Barratt et al. (2012) notes the restricted ‘play space’ for children in shared accommodation, which might feature as an additional source of stress for parents. One source (Rugg et al., 2011) draws attention to the potential conflicts that arise between parents in the same shared properties, who want their children to be able to stay overnight. Plans have to work around other parents, and child contact often had to be rearranged, due to the unpredictability of other tenants in the accommodation. Other issues included the unsuitability of the environment of shared accommodation for children, with concerns around noise, cleanliness, and the unknown backgrounds of other tenants (Rugg et al., 2011).

Vulnerability

Serious concerns have been raised about the suitability of shared accommodation for vulnerable groups, and, as the report by Unison (2014) found, this has become more pressing recently, with higher numbers of vulnerable people accessing shared accommodation. Professor Suzanne Fitzpatrick told the Work and Pensions Select Committee (2014) that vulnerable younger people and women fleeing domestic violence might now be expected to share accommodation with ‘older younger’ people with mental health or drug and alcohol problems, or be placed in an insecure environment where they feel unsafe. The report by Unison (2014) concurs: for young women who have experienced domestic violence, living among males who may be disposed to act violently or aggressively might put women at further risk of harm and put further strain on their mental well-being.

Living in shared accommodation might also impact those with mental health problems, as noted earlier, poor quality environments and other tenants’ behaviour may exacerbate feelings of stress and anxiety (Crisis, 2014).

Ex-offender sharers, especially those in ‘stranger shares’ where criminal activity is taking place, are at risk of reoffending if placed in this kind of unstable environment (Rugg et al., 2011). Likewise, tenants who are recovering from addiction are placed at extra risk in an environment where drug-taking activity is common (Rugg et al., 2011). A final question concerns the suitability of shared accommodation for formerly homeless people who may have a range of support needs. The possibility of feeling the need to escape from unsuitable shared accommodation contexts may lead to repeat episodes of homelessness. Indeed, this issue has been identified as an area that demands further exploration (Rugg et al., 2011).

On-site management difficulties

Shared accommodation might either be arranged as a joint tenancy, where all tenants are liable to meet the rent payments, or as a number of separate tenancies where tenants pay separate rent payments but share the same facilities. Rugg et al. (2011) found that some tenants experienced difficulties in managing joint tenancies. Some faced problems when other tenants did not pay their share of the rent. This problem also arose when relationships ended and the party remaining in the accommodation could not afford to cover the rent, given the change in circumstances.

Inherent to the experience of sharing, and evidenced in several sources, are the conflicts that might arise between tenants and the difficulty of coping with low-level anti-social behaviour. This tension is inevitably heightened when it involves two strangers, who may find it more difficult to arrive at a compromise, or where one party might be afraid to broach the subject if they are unsure about the reaction of the other to criticism (Rugg et al., 2011). Barratt et al. summarise this issue succinctly in relation to HMOs, suggesting that shared accommodation offers significantly less control than other types of housing: ‘HMOs by their definition, include some element of shared space, which instantly reduces the control that individual residents have over the space in which they live’ (2012: 41).

Examples of good practice, where residents felt that managing shared tenancies ‘worked’, were reported in properties where landlords took a more active role in ‘generic property management’, and dealt with problems promptly. One such property had a security officer and rules in place to disallow overnight visits from adults while allowing visits from non-resident children with the permission of the landlord, as well as rooms set aside for that purpose (Rugg et al., 2011). Instances of good sharing practices from other studies cite the importance of ‘fair cleaning rotas’, and the encouragement of resident involvement in management. This may include the opportunity to have input in the selection of new tenants or in setting criteria for the prospective tenant to meet (Vickery and Mole, 2007).

Insecurity

Poor quality housing has been shown to lead to insecurity through problems with maintenance and other potential dangers from the accommodation, or simply having to live with other tenants’ behaviour (Barratt et al., 2012). Previous research has indicated that problems of crime – including anti-social behaviour, theft and violence – may arise in shared accommodation (Harvey and Houston, 2005; Rugg, 2008; Shelter Scotland, 2009). This will inevitably exacerbate tenants’ feelings of unease and insecurity about where they are living. Rugg et al. (2011) reported tenants’ concerns over the strength of locks on rooms and front doors. This evidence is reaffirmed by Unison (2014), who noted concern over the poor quality of shared accommodation with broken locks, many keys in circulation, people wandering in and out, and residents not knowing who they were sharing with.

Respondents in Rugg et al. (2011) were similarly anxious about the anonymity of other residents, especially given the high turnover of tenants in shared accommodation. In one case, a female respondent felt that her personal safety was directly at risk after having her door ‘kicked in’ during a rowdy party whilst living at a men-only house. Rugg et al. (2011) found drug use to be prevalent in the shared accommodation visited as part of the research, and acts of minor theft all added to feelings of insecurity. Insecure environments are even more unsuited for particular groups: those with non-resident children; those with mental and physical health problems, past dependency or offending problems; and those escaping domestic violence.

Analysis of the available evidence indicates that experiences of sharing differ markedly according to the group in question. It can be a starkly different experience for students, young professionals, low-income tenants and those from more vulnerable groups. This section has highlighted literature relating to the increased number of individuals under the age of 35 forced to share accommodation under the SAR. Although this review has unearthed more challenges than benefits in terms of sharing accommodation under SAR, in some cases sharing might be a viable housing solution. Some evidence paints shared living environments in a more positive light if managed in the correct way, especially if it takes full account of tenants’ needs and devolves some of the decision-making and micro-managing processes to tenants themselves.

The Sharing Solutions Programme: background and methods

The Sharing Solutions Programme began in October 2013 and concluded in March 2015. It was funded by a grant of £800,000 from DCLG and was administered by Crisis, the national charity for single homeless people. The aims of the Sharing Solutions programme were threefold: to develop new models to encourage and support landlords to rent their properties to claimants on the Shared Accommodation Rate; to improve the availability of shared accommodation; and to improve the support for tenants to sustain their tenancies.

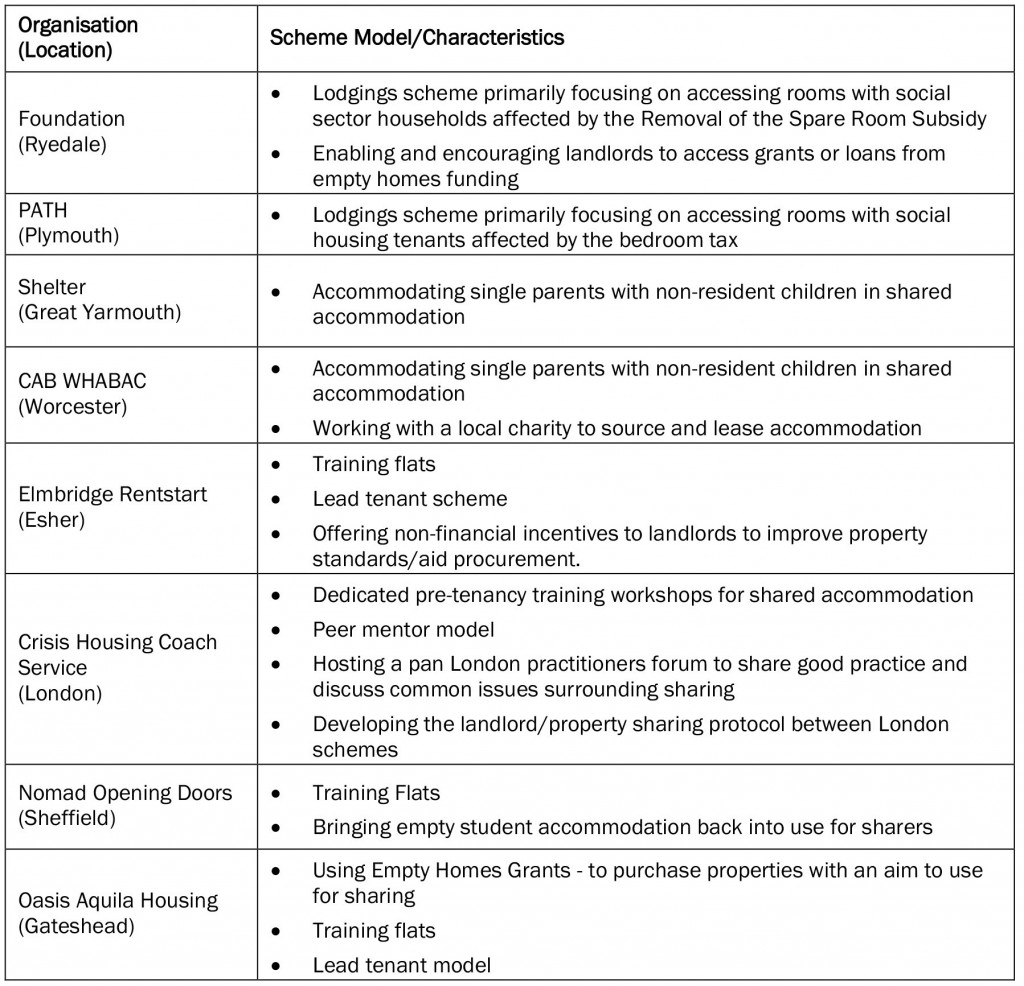

The programme consisted of eight schemes distributed throughout England reflecting different housing markets, in London, Sheffield, Great Yarmouth, Ryedale, Plymouth, Esher, Worcester and Gateshead respectively (Figure 1.1 shows the Programme’s geographical coverage). A variety of innovative ‘sharing solutions models’ were piloted, including training tenancies, lodgings, accommodating single parents with non-resident children, utilising void accommodation, appointment of a ‘lead tenant’, and peer mentors (Table 1.1 provides further details of each scheme in operation and the model of support it was based on).

The schemes were set up to pilot, develop and promote new models for establishing successful and sustainable sharing arrangements for tenants in housing need. Each scheme received £90,000 over 15 months, and Crisis retained £80,000 towards its staffing and administration costs. The programme was targeted mainly at the PRS and at individuals who were receiving Housing Benefit and only eligible for the SAR of the LHA. The programme also encompassed partnerships with social sector housing organisations and individuals for whom sharing could be a preferable financial option (for instance, those who are eligible for a self-contained one-bedroom flat but who, for financial reasons, choose to share), or a preferable social option (for instance, where sharing could bring increased social interaction).

In December 2014, the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research (CRESR) at Sheffield Hallam University undertook an evaluation of the Sharing Solutions Programme. The objectives of the evaluation were to: assess the extent to which the project met its aims and objectives; provide evidence of successful sharing models and lessons learned from the pilot schemes; provide evidence of how the pilots were successful; provide evidence of the additional value given by Crisis to the pilot schemes, through support, advice and dissemination of best practice; provide evidence of the additional value given by the programme to the wider environment and external sharing schemes through the dissemination of best practice; and explore the broader implications for policy and practice so as to inform the future development of shared accommodation options in the private rented sector.

The evaluation involved initial qualitative interviews with three Crisis officers and five members of the Advisory Group; but consisted mainly of in-depth case studies of the eight pilot projects involved in the Sharing Solutions Programme. These detailed case studies entailed in-depth qualitative interviews with project workers; interviews with tenants supported through the schemes; interviews with key representatives of partner organisations involved in the programme (including landlords and supporting local authorities); and analysis of local monitoring data and other available information gathered by the schemes. The pilots were, in themselves, a test of viability of different ‘sharing solutions’, or innovative models of sharing for single people in housing need. When measuring ‘success’ of the programme as a whole, we considered tenant and landlord outcomes; how far the programme met its initial aims, as outlined above; as well as overall delivery achievements based on monitoring data supplied by Crisis.

The issues around availability of, and access to, shared accommodation are discussed in the following sections in relation to the Sharing Solutions Programme pilots, to highlight the challenges and identify solutions around sharing in the private rented sector for groups in housing need.

Cultures of Sharing

Requiring only a short-term commitment, sharing in the PRS can be an ideal and positive housing choice at particular points in the life course. Sharing is, however, culturally associated with youth and transience and the recent change to the LHA rates has extended the age at which single people are expected to share beyond this cultural norm.

It is important to note that cultures of sharing are not universal or fixed, but shift and change in response to housing market conditions and local context. For example, in London (and other high-demand markets) where owner occupation and self- contained rented accommodation is financially beyond reach even for those with decent incomes, it is already common and culturally acceptable for people to share accommodation in the PRS into their 30s, and increasingly beyond. In contrast, stakeholders reported no such ‘culture of sharing’ in areas such as Gateshead, where self-contained accommodation is still reportedly easy to access and affordable. Stakeholders there reported that rents in the PRS are low and social housing relatively easy to secure and so sharing is simply not the norm, at any age. A project manager said that it was an ‘uphill battle to convince people to consider sharing’. However, the scheme was able to make inroads by improving the supply of shared accommodation in Gateshead, using their own properties (former empty homes, purchased and refurbished with a grant from DCLG) and properties sourced from the PRS.

The presence of a large student population was also found to engender broader cultures of sharing, with one scheme in Sheffield encountering less resistance to the idea of sharing amongst their clients than other Sharing Solutions pilot schemes. In contrast, talking about the Sharing Solutions scheme in Great Yarmouth, one stakeholder suggested that: ‘it’s not like a university town where there’s big sharing cultures, so it was kind of bucking that trend’.

However, there were reports of considerable resistance to sharing amongst the client group from all pilot schemes. Stakeholders reported that they had to make significant efforts to shift cultural norms and expectations. In areas where, historically, social housing tenancies have been easy to secure (Sheffield, for example) expectations persisted about accessing a one-bedroom flat in this sector. As one stakeholder explained:

People just need a massive reality check. The good old days of seeing an empty property and going to the council and saying ‘can I have it?’ are well and truly gone. When I first started working with homeless people – which was about 15 years ago – it was like that. I started off working with [X organisation] when the bidding system came in, just in certain parts of [the area] so with our clients, we’d put one bid on and we’d get a house or we’d get a flat and a lot of people think it’s still like that. So I have to say to people ‘if you haven’t got priority you’re looking at five or seven years for a one bedroom flat’. They don’t believe you but it is the case.,

Clients’ resistance to sharing was frequently linked to concerns about who they would be sharing with as well as a general preference for self-contained housing. As one client said, ‘I was a bit scared because I’d never been in shared before but now I like it, I enjoy it…’ (Sheffield); ‘because I was moving in with people I didn’t know I was a bit nervous’ (Great Yarmouth). There were some suggestions that welfare reforms were having an impact on clients’ attitudes to sharing. One client, who had moved into a shared house from his family home explained how he would ‘share again in a heartbeat’ (Worcester); another that she was ‘not really in a rush […] to go. If after six months I got priority and they said “you’ve got to move” […] I’d be like “no, I don’t wanna move” because it’s not somewhere I wanna move and I’m happy where I am’ (Sheffield).

Still, this attitudinal shift appeared to be minor at the current time, and many clients saw their shared tenancy as a step to a self-contained flat. As one client said, ‘this has just been a place to stay in the meantime until I find a better place’ (Great Yarmouth), and another that ‘it’s just basically until I can get a decent job and get my life sorted’ (Great Yarmouth). Several stakeholders reported that managing client expectations about their housing options was one of the most challenging aspects of the Programme. For example:

No matter how well you can try manage expectations with clients, some clients would rather carry on as they are if they can’t have what they want or if what they want isn’t affordable to them. It’s very difficult to talk to people about affordability when… if people come in and they’re under 25 and they want the one bedroom flat, we’d have to explain that out of the £57 a week jobseekers, by the time you’ve paid top-up for a self-contained place and then you’ve got to think about your food and everything else, it’s just not viable a lot of the time and people would rather just not hear that and just do it anyway and find themselves homeless again in a couple of months.

Sometimes this is a bit of a reality check for people because one thing that does come across all the time is when we tell people ‘we can help you find a room in a shared house’ they say ‘I don’t want that, I want a one-bedroom flat’. So part of this [workshop] is looking at why you can’t have a one-bedroom flat, how much that would cost, and how much you’re actually going to get in HB…and looking at the difference between being in a one bedroom flat… You’re gonna be working and coming home and you’re not going anywhere else; if you’re living in a shared property you’ve got a little bit of money to play with so you can have a social life as well.

As the quote directly above illustrates, pilot schemes were taking a proactive approach to clients’ reticence about shared accommodation, an important step in a potentially slow process of cultural change.

Managing sharing

The barriers and challenges encountered by single people claiming HB – access to the PRS, securing accommodation at an affordable (SAR) rate – mean that intervention in the market is required, and the Sharing Solutions Programme highlights this. To improve the availability of shared accommodation and the sustainability of shared tenancies requires managing from both a supply side (landlords) and a demand side (tenants). Each pilot scheme had to negotiate a series of considerations and challenges about managing shared accommodation.

A key consideration for landlords managing shared accommodation and for tenants sharing is the type of tenancy agreement – a single shared agreement or individual agreements for each tenant. Individual tenancy agreements are more cumbersome from the landlord perspective but offer certain protections for tenants.

One scheme elected to use a protected license agreement in its partnership with a local Housing Association, on the basis that it offered greater flexibility where sharers were struggling. This raised issues around offering clients the strongest security of tenure, but it was agreed to trial a license in the context of training flats. The project manager explained their rationale for the approach:

I absolutely agree that we should be giving the strongest security of tenure that we can, but we also have to balance that with the safety of the other person that lives in the property. There have been instances where issues around violence and aggression have come to light and we need to be able to keep that other person living there as safe as possible and if a situation presented itself.

Another scheme similarly opted to use license agreements for the first six months of the tenancy; tenants were then given the option to move on to Assured Shorthold Tenancies (ASTs), if rent accounts were up-to-date. This approach reportedly worked well and was done in the best interest of clients for whom an AST would be too great a risk. As one stakeholder said, ‘if we offered everyone ASTs straight off… it would be too much of a gamble and it would be too expensive for the ones that don’t work’. Some tenants chose to remain on a license agreement after the six month period, as it allowed a greater degree of flexibility.

By contrast, two other schemes adopted ASTs. Both project managers were confident that the law provided adequate leverage to remove a tenant who posed a risk to others.

There is no right or wrong answer here, and on the basis that training flats are offered for a short period (normally six months), and the client is supported intensively by an established PRS project, a license can be effective without diminishing a client’s security of tenure. License agreements can be beneficial for the tenant by allowing more flexibility, and present less of a risk for the scheme. Applying licenses to a less regulated scenario, however, would be more problematic.

Who is responsible for managing the property is also a key consideration – whether the property is managed directly by/via the landlord or through a leasing agency. Again, the pilot schemes responded to this in different ways and both had their merits. Where pilot schemes had direct control for properties it was considered to be positive as it made close monitoring more straightforward; for clients it meant they did not deal directly with a landlord. This could also be viewed in a negative way – that clients are not exposed to real world conditions – however none of the projects considered this to be a critical issue.

Experienced staff and experienced projects achieved better results, with knowledge of the local PRS and understanding of how to engage and converse with landlords, being critical to success. All pilot schemes demonstrated a clear understanding of their clients’ needs and the state of the local housing market, and all had access to advice workers with broad experiences of supporting clients beyond housing options. However, it should be recognised that such experienced PRS schemes do not exist everywhere there is a need for them. Managing sharing is complex and less experienced schemes may struggle to meet the needs of clients and landlords; local authority departments will not be sufficiently resourced to provide the intensity of support required.

Pilot schemes identified that appropriate matches were a critical element to ensuring that sharing was successful. There are, therefore, important questions about how far landlords should attempt to ‘match’ tenants and, if so, how this is best done effectively. Matching was described as ‘more art than science’ and that it needed to be pragmatic. In one case, the project worker would assess clients and come to a judgement, and then allow clients to meet up. However, there were occasions when a room became available, and more pragmatic decisions had to be taken. Stakeholders in the pilot schemes often reported that getting a good match was as much to do with their instincts rather than anything a formative assessment could determine. However, a few guiding principles did emerge: giving tenants some choice or involvement in the process was found to be important; and tenants with different lifestyles often made good sharers (working different shifts, eating and socialising at different times often gave greater privacy in a dwelling). However, there was evidence from sharers that a mix of ‘working’ and ‘non-working’ tenants could lead to tensions, particularly around noise-disturbance when sleeping times differed.

Throughout the Programme, there had been successful examples of shared accommodation consisting of a mix of different people. One stakeholder commented that:

Mixed houses can enable better sustainment. Sharing Solutions is not demarcating people into housing silos. It’s encouraging clients to mix and be housed in general communities.

The provision, form and intensity of tenancy support are further considerations for landlords and organisations developing sharing models. All of the schemes were offering intensive tenancy support and reported this as critical to the success of the Programme. Pre-tenancy training, training flats, regular visits, and peer mentoring were forms of support used by the pilot schemes that proved particularly useful.

Bond schemes can also be essential to enable vulnerable people and those with low-incomes to access shared accommodation. Many vulnerable people cannot save a deposit, particularly those living in hostels and individuals coming from a family or relationship breakdown. Some landlords, particularly those taking in lodgers, do not require a deposit, making this type of accommodation particularly attractive to vulnerable groups. All of the pilot schemes had access to bond schemes, and this was viewed as essential for clients to access the PRS.

Assessing tenants’ suitability for a shared housing scheme, and their suitability to form a household with the other resident tenants, is not a straightforward process. Stakeholders explained that they go through a fairly lengthy and detailed process of understanding the applicants’ situations and needs, exploring their housing history, support needs, and financial circumstances and capabilities. A stakeholder explained, however, that:

It’s not necessarily any of those things that would rule someone out… we’d look at what their offences are and what impact that’s going to have on their housing and we’d work through that.

Similarly, a stakeholder explained that poor mental health can render shared accommodation inappropriate for some clients, but by no means all.

For those pilot schemes seeking to provide for absent fathers, safety concerns were considered to be very important – and difficult to pursue. One scheme, for instance, had planned to ask tenants to complete a Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) check but found that these could only be carried out on volunteers or employees. They managed to overcome this obstacle by ensuring that prospective tenants applied for a Police Certificate which showed all convictions, warnings, reprimands and cautions recorded on UK Police Systems. This pilot experienced significant delays in filling all the rooms in the property as clients did not always disclose their offences immediately.

Support for tenants to sustain tenancies

All pilot schemes provided, and emphasised the importance of, tenancy support. There was a consensus that without support, tenancies were less likely to be sustained. One stakeholder commented that the clients most likely to sustain their tenancy beyond six months were those who had been referred from a local supported housing project, contrasting with those clients referred to them by the local authority.

Pre-tenancy advice and support was commonplace. At one scheme, ‘Tenancy Ready Training’ was available for those who needed it, providing advice and information about tenancy agreements, money, budgeting, healthy lifestyles, being a ‘good tenant’ and using choice based letting schemes. In other schemes, pre-tenancy training was considered so important that attendance at a workshop was compulsory for engagement with the project. One project worker explained:

We do get people when we tell them they’ve got to do these workshop who say ‘I’m not doing it’ but we say ‘then we’re not re-housing you’… or we get people who say ‘I’ve had my own tenancy before’… well it’s obviously failed or they wouldn’t be here.

Several schemes reported that getting people to training sessions was often difficult. There was a fine balance to be drawn between being inflexible (such as refusing to work with clients who missed training) and being very flexible (as one worker put it – ‘being far too soft’ which led tenants to refuse to shoulder support).

Most schemes had ongoing systems of support or review in place so that issues (from the point of view of the landlord or the tenant) could be identified and addressed in a timely manner. In many of the schemes, tenants were visited or contacted by a support worker several times a week. This is, of course, very intensive support. For some clients, this high level of support was provided for the duration of the tenancy, or for the first six months. In several schemes a formal ‘health check’ of the tenancy was carried out with the client every two months.

Although described as a transitional dwelling by some, clients valued their places in shared accommodation namely due to the accompanying support they received – whether from the formal training and skills packages delivered by the schemes, or from being part of an informal support network comprised of fellow housemates. Project staff supported tenants with a range of issues that often stretched beyond housing, to resolving issues with benefits, managing budgets and other finances, employability, and making referrals to other support agencies (such as mental health or counselling services) where necessary. This support often made all the difference to tenants’ experiences of shared accommodation, and was especially vital for tenants with complex pasts and higher support needs. Such groups of tenants may have struggled both to maintain regular tenancies without this level of support, and to cope with other related issues that put tenancies at risk. In fact, some respondents cited ‘being able to support themselves’ as one of the main barriers to moving into self-contained housing in the private rented sector straight away; and others contrasted their current experience to past housing situations where they had been left to flounder without any support. One tenant recounted, ‘[when I was lodging], I was chucked in the deep end’. In some cases, support by project staff was treated as a ‘safety net’ – as something to fall back on when needed – encapsulated by the statement: ‘I know if I did have problems I could go to Shelter so I feel a lot better knowing they’re there. So I don’t really worry too much’. Other times support was quite heavily relied upon and tenants became more dependent on it: ‘Say the house was a mess and [X] didn’t come, I wouldn’t have anyone to talk to about it and it wouldn’t get sorted’.

Here, there is a fine balance to be struck between enough and too much support. While ‘too much’ support risks tenants becoming co-dependent and perhaps, not taking responsibility for managing tenancies themselves, ‘too little’ support – particularly for more vulnerable adults – in the private rented sector risks the tenancy itself.

This issue also materialised at Shelter Great Yarmouth where support was less intensive and relied on tenants going to the scheme themselves rather than a project worker routinely visiting them. This scheme found that tenants were reluctant to report problems in time, and often ‘buried their heads in the sand’ as problems spiralled out of control:

I think I would like to find an extra way of reaching people before they hit that point of crisis. With the support and everything, it’s good but you… it’s really hard to detect the problem because a lot of times the clients are telling you everything’s okay and it’s not until you hear from the landlord… so I think any way of having some kind of better way of getting them to come forward more readily would be good but I’m not quite sure…how we could improve that really…

The advantages to tenants of receiving a high level of support were clear and the requirement to provide it were understandable, given the benefits to homelessness prevention. Tenants often face very precarious housing circumstances in the private rented sector where relatively minor breeches of a tenancy agreement, disagreements with a landlord or with other tenants may result in the termination of a tenancy.

The pilots reported that such intensive support was an important factor in encouraging landlords to accommodate their clients. One scheme operating in a high cost PRS market area, where property was difficult to source, reported that their reputation for providing intensive support with clients was essential to maintaining the involvement of landlords.

Some organisations had noticed an increase in levels of tenancy sustainment since launching their Sharing Solutions scheme, attributing this partly to the support they were able to offer, the attention they were able to pay to tenant selection and allocation, and the experience accrued. A stakeholder made the following comment:

If I look at what we were doing a couple of years ago, we did have a fair turnover really and it’s not like that now. A lot of that is to do with the staff that we have here at this moment, the people they select, and putting them in the right place.

Other stakeholders from this scheme made similar comments but also pointed out that without such schemes, some tenants would simply fall through the net:

Without what we do, a lot of people would be lost.

Normally, you wouldn’t call your landlord if you’d been sanctioned, whereas because we go over once a week and give that support, or they know they can pop into the office, they’ll just come in and say ‘this has happened’ or ‘what can I do about this?’ So I think they’ve got as much as you can give to give them skills to be able to maintain [a tenancy] and hopefully move on to other types of accommodation and they’ve got those skills.

Conclusions

The increased pressure on housing markets across the country (resulting from housing supply constraints, patterns of new household formation, persistent affordability pressures, and reductions in housing and other welfare benefits) make it inevitable that more people will move into shared accommodation as the most financially viable solution to their housing needs. However, there is also a reluctance to enter into sharing with ‘strangers’ rather than family members or friends, and these concerns are highlighted for many members of vulnerable groups facing challenges such as living with others, gaining access to the PRS, and sustaining a tenancy. In terms of supply, landlords are often reluctant to take on shared accommodation due to the management complexities (and costs) that can arise (for example on termination of tenancy) and because they fear returns may be lower than for self-contained housing. In this context, Sharing Solutions was an opportune programme which was able to test out various ideas for making shared accommodation a more attractive option for tenants. The evidence here suggests that a number of the potential barriers to developing shared accommodation can be overcome if additional support is provided.

The Sharing Solutions Programme raised awareness about how to deal with some of the challenges of shared accommodation, and was borne out of a desire by the Coalition Government to find ways of making the PRS work better for young, single people in the face of changes to the welfare system. The Programme represented a good start, but much more will need to be done in the future to share good practice – not just from the eight pilot projects but more widely. There are few standard ‘off-the-shelf’ practices that can be advocated across all areas, as their utility and relevance will inevitably be mediated by the local housing market context – whether there is a prominent student market or not, whether there is an established culture of sharing, whether it is a low or high demand area, whether the PRS is dominated by a few large professional landlords and agents, or by a host of smaller landlords. The Sharing Solutions Programme is continuing in a more limited form, via support from Crisis. Six schemes are being supported to continue with a view to extending and promoting good practice. Crisis is also keen to further develop and promote its Sharing Solutions Toolkit (Crisis, 2015) as part its Private Renting Programme 2014-2016, which is funded by DCLG and provides grant funding and support to 42 private renting access projects across England. For example, the Sharing Solutions pilot scheme in Sheffield, run by Nomad Opening Doors has been extended and enhanced to create a new service (see nomadsheffield.co.uk/accommodation), supported by grants from the Big Lottery Fund and Crisis. This new service, called SmartSteps, aims to support 300 young people who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless into stable tenancies.

The Sharing Solutions Programme demonstrated that shared accommodation can be made to work effectively for low-income tenants who are in receipt of welfare benefits. The evidence in this paper is that such interventions must be coupled with support, advice and other ‘enabling’ services (such as a deposit guarantee scheme which supports clients who cannot afford a deposit and gives private landlords greater assurances when renting to more vulnerable people). The Sharing Solutions Programme was delivered through established private rented sector access schemes that deliver this range of services. They are funded mainly by local authority grants and commissioning, but increasingly they are supported by grants from charities as public expenditure has been reduced in this decade. Such schemes provide a range of services to vulnerable people seeking housing including: deposit guarantee schemes, tenancy training and support, landlord negotiation and signposting to other services to deal with more personal problems facing clients. While these services can be costly, they are required to provide shared accommodation that is sustained and affordable. Analysis of the eight pilot schemes indicated that staff, volunteers and stakeholders all understood the needs of the client groups involved and had experience of engaging with, and intervening in, the private rented sector. However, PRS access schemes are not established in all areas of the UK, and where services are not accessible, access to the private rented sector is harder for vulnerable groups, and near impossible for some individuals.

In the current (and future) spending climate, it is essential that any new scheme can produce savings as well as meet housing needs. The use of the Crisis Making it Count tool showed that for every £1 of grant funding in the Programme, £5.21 of savings was generated in savings attributed to homelessness prevention (see Batty et al., 2015). The positive outcomes for tenants and landlords discussed here indicate that investment in PRS access projects to promote Sharing Solutions was a worthwhile and cost effective policy. But it requires the funds to kick-start schemes, and intensive support is required to sustain tenancies in the long-run, both to assist the tenant, and to incentivise landlords to rent their properties to vulnerable people. This comes at a price; but this paper shows that the eventual benefits of programmes like Sharing Solutions will soon outweigh these costs, if they can thereby prevent an increase in homelessness amongst this ‘at risk’ group on the margins of the housing market.

Stephen Green and Lindsey McCarthy, CRESR, Unit 10 Science Park, Howard Street, Sheffield, S1 1WB. Email: stephen.green@shu.ac.uk / l.mccarthy@shu.ac.uk

Barratt, C. (2011) Sharing and Sanity: How Houses in Multiple Occupation may threaten the Mental Health of Residents. Paper presented at Housing Studies Association Conference, University of York, April 2011.

Barratt, C., Kitcher, C. and Stewart, J. (2012) Beyond Safety to Wellbeing: How Local Authorities can Mitigate the Mental Health Risks of Living in Houses in Multiple Occupation. Journal of Environmental Health Research, 12, 1, 39-50.

Batty, E., Cole, I., Green, S., McCarthy, L. and Reeve, K. (2015) Evaluation of the Sharing Solutions Programme. London: Crisis.

Beatty, C., Cole, I., Powell, R., Kemp, P., Brewer, M., Browne, J., Emmerson, C., Hood, A. and Joyce, R. (2014) The Impact of Recent Reforms to Local Housing Allowance: Summary of Key Findings. London: DWP.

Clapham, D., Mackie, P., Orford, S., Thomas, I. and Buckley, K. (2014) The Housing Pathways of Young People in the UK. Environment and Planning A, 46, 8, 2016-2031. CrossRef link

Crisis (2012) No Room Available: Study of the Availability of Shared Accommodation. London: Crisis.

Crisis (2014) Making it Count: Headline Data, October to December 2014. London: Crisis.

Crisis (2014) Shut Out: Young People, Housing Benefit and Homelessness. London: Crisis.

Crisis (2015) A Shared Approach: Setting up and Supporting Tenancies in Shared Houses. London: Crisis.

Department of Health (2010) Confident Communities: Brighter Futures. London: HMSO.

Evans, G., Wells, N. and Moch, A. (2003) Housing and Mental Health: A Review of the Evidence and a Methodological and Conceptual Critique. Journal of Social Issues, 59, 3, 475-500. CrossRef link

Harvey, J. and Houston, D. (2005) Research into the Single Room Rent Regulations, Research report 243. London: DWP.

Heath, S. and Kenyon, E. (2001) Single Young Professionals and Shared Household Living. Journal of Youth Studies, 4, 1, 83-100. CrossRef link

Kemp, P.A. (2011) Low-Income Tenants in the Private Rented Housing Market. Housing Studies, 26, 7-8, 1019-1034. CrossRef link

Kemp, P.A. and Rugg, J. (1998) The Impact of Housing Benefit Restrictions on Young Single People Living in Privately Rented Accommodation. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Kenyon, E. (2000) In their Own Words: A Biographical Approach to the Study of Young Adults’ Household Formation. Paper presented at British Sociological Association Annual Conference, University of York, April 2000.

Kenyon, E. and Heath, S. (2001) Choosing This Life: Narratives of Choice amongst House Sharers. Housing Studies, 16, 5, 619-635. CrossRef link

Page, B. (2002) Poor Housing and Mental Health in the United Kingdom: Changing the Focus for Intervention. Journal of Environmental Health Research, 1, 1. CrossRef link

Rugg, J. (2008) A Route to Homelessness? A Study of Why Private Sector Tenants become Homeless. London: Shelter.

Rugg, J., Rhodes, D. and Wilcox, S. (2011) Unfair Shares: A Report on the Impact of Extending the Shared Accommodation Rate of Housing Benefit. London: University of York and Crisis, available at: www.york.ac.uk/chp/expertise/finance-benefits/publication

Shaw, M., Danny, D. and Brimblecombe, N. (1998) Health Problems in Houses in Multiple Occupation. Environmental Health Journal, 106, 10, 280-281.

Shelter Scotland (2009) Review of Research on Disadvantaged and Potentially Vulnerable Households in the Private Rented Sector. Glasgow: Consumer Focus Scotland.

Unison (2014) A New Housing Benefit Deal for Young People. London: Unison.

Vickery, L. and Mole, V. (2007) Shared Living in Supported Housing – Client Responses and Business Decisions. Housing, Care and Support, 10, 4, 20-26. CrossRef link

Work and Pensions Committee (2014) Support for Housing Costs in the Reformed Welfare System, Fourth Report of Session 2013-14. London: HMSO.