Abstract

The benefits of urban greenspace are both manifold and well-established; its relationship to social and spatial inequalities less so. Drawing on and updating a five-part framework (distribution, recognition, participation, responsibility and capabilities), we explore the justice dimensions of urban greenspace in Newcastle upon Tyne. We argue that justice in this respect is not just about where greenspace is located in a city, but concerns the characteristics of the greenspace itself, how these relate to the characteristics of local communities, their wellbeing and opportunities. In the context of Newcastle’s changing demography and contemporary moves to transfer the management of Newcastle’s parks and allotments to a charitable trust, we make the case for participation as the central Environmental Justice (EJ) dimension for the city.

Introduction

Environmental justice (EJ) has its origins in political struggles taking place in the 1950s and 60s, where ethnic minority communities sought to challenge implicit institutional racism in the location of environmental blights such as pollution, contamination and waste facilities (Taylor, 2002). The evidence of a strong tendency to locate such environmental burdens near or within ethnic minority communities was established by studies in the ensuing decades (e.g. UCC, 1987; Bullard, 1999; Goldman, 1996). These also moved the struggle beyond exclusive emphasis on the spatial association with minority ethnicity to include proximity to “women, children and the poor” (Cutter, 1995: 113). Other vulnerabilities such as age, health and disability also entered the concept (Lucas et al., 2004). Equally, the substantive scope of environmental justice has latterly expanded “beyond toxics” (Agyeman and Warner, 2002: 8-9) to include a wider range of environmental hazards and disbenefits, and eventually came to include environmental resources and benefits, too (Benford, 2005; Walker, 2009: 616-7; US EPA, 2012: 7), among which is urban greenspace.

The multiple benefits of urban greenspace for issues such as air quality, emissions mitigation, water regulation, human health, social networks and place belonging – are established and well-rehearsed (Davoudi and Brooks, 2016; HoC CLGC, 2017; Kimpton, 2017). Further, new research regularly adds fresh dimensions to the range of greenspace benefits, with recent findings including an association with higher levels of happiness (White et al., 2013), social capital (Zelenski et al., 2015) and perception of greater community cohesion (Weinstein et al., 2015).

Despite the increasing recognition of the benefits of urban greenspaces there is a growing disinvestment in them at local authority level, connected with a more than 25 per cent reduction in local authority revenues since 2010 (NAO, 2014). According to the Heritage Lottery Fund’s biannual State of the UK’s Public Parks 2016 report, 92 per cent of UK local authority parks departments had experienced cuts to their budgets in the previous three years, while 95 per cent expected further cuts in the following three years (HLF, 2016: 3). Showing an escalating trend, these figures are up respectively six per cent and eight per cent from the percentages reported in 2014.

Already in 2008, under a New Labour administration, a government agency was recommending ways of making parks pay for themselves (CABE, 2008). More recently in response to the acute pressures on greenspace budgets, new approaches to raising funds for greenspace provision have been encouraged by the voluntary sector through the ‘Rethinking Parks’ programme (Nesta, HLF and TLF, 2016). In response, local authorities have developed a raft of revenue-raising initiatives that both challenge parks’ established status as free and open access spaces and have implications upon their value for nature (Evans, 2015; Moore, 2017).

Following the kinds of recommendations noted above around making parks financially self-sustaining, in 2017, Newcastle City Council voted to transfer the management of 33 of its larger parks and 50 hectares of allotments to a charitable trust under a lease arrangement, becoming the first local authority in the UK to do so (Future Parks, 2018). At the time of writing, this transfer is in process and will not take full effect until the end of 2018, but as a pioneering experiment it provides a context for reconsideration of the environmental justice of greenspace in the city.

This paper develops and updates an environmental justice study of Newcastle’s environmental benefits and burdens originally commissioned by the Institute for Local Governance for the city’s Fairness Commission in 2011. In line with this work (Davoudi and Brooks, 2012; 2016), we introduce a framework which moves beyond the traditional focus on distribution to include four other environmental justice dimensions: recognition, participation, capabilities and responsibility (the last of these original to the authors’ EJ approach). Looking at the recent changes to the management of Newcastle’s parks and allotments through this multi-dimensional lens allows us to fully explore the potential consequences for vulnerable and disadvantaged groups.

In the following sections we elaborate on these dimensions in turn and discuss how they can shed light on the environmental justice of greenspace in Newcastle City. Following this, we consider the implications of greenspace management transfer for environmental justice and argue that in the context of this recent development, participation has become the central issue for the environmental justice of greenspace in the city. We conclude with some suggestions for developing this area of research.

A pluralistic approach to environmental justice of urban greenspace in Newcastle City

In this section greenspace is considered in relation to five dimensions of environmental justice: distribution, recognition, participation, capabilities, and responsibility. While it is clearer to treat these dimensions as if they were separate, there are many overlaps between them, and we have attempted to point these out where possible. To illustrate each of the five environmental justice dimensions, examples are selected from the provision and management of greenspace in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Distribution

Distribution is about who gets what in terms of, quantity of and proximity to greenspace as well as its quality.

Proximity to greenspace matters if people are to benefit from some of the positive impacts of greenspace on, for example, air quality and noise abatement (UK NEA, 2011: 390), irrespective of actually using the greenspace. People are also more likely to use a park that is situated near to them – in particular children and older people, as well as families with young children – and to access it using an active travel method such as by foot or bicycle, with obvious benefits for the environment (Bird, 2004; CSD, 2011; UK NEA, 2011: 390).

While there is evidence of how greenspace – especially better managed and quality greenspace — can raise property values (Panduro and Veie, 2013; Voicu and Been, 2008), there are also indications that greenspace contributes to reducing stress levels in economically deprived areas (Ward Thompson et al., 2016), thus contributing to reducing health inequalities. The established positive health impacts of greenspace in economically deprived areas have led it to be described as ‘equigenic’ (Mitchell and Popham, 2008; Mitchell et al., 2015).

Therefore, in terms of environmental justice what matters is the location of greenspace in relation to deprived and disadvantaged communities, with research evidence showing that disadvantaged communities are less likely to live near to greenspace (CABE, 2010a; Heynen et al., 2006; Marmot, 2010). Thus, they have less access to the various greenspace benefits mapped out above, adding to their existing disadvantage.

Retro-adding significant areas of greenspace to new developments can be achieved through the Community Infrastructure Levy, a local authority charge on developers which into force in 2010. Adding greenspace to the existing urban core is harder, but has been achieved in a few cases, through initiatives to turn brownfield and contaminated lands into public amenities (see for example De Sousa, 2004; Owen, 2008). Furthermore, small areas are increasingly added through the creation of ‘Pocket Parks’ on parcels of land – some as small as a tennis court – that are not suitable for alternative uses. The government recently committed £1.5 million to the creation of more of these (UK Government, 2016). However, there may be some questions about the benefits of small greenspace areas with comparison to larger ones, in terms of their far more limited environmental impacts and unsuitability for a range of uses.

Turning now to Newcastle upon Tyne, this is a city marked by spatial inequalities that go beyond income and wealth, including for example, a significant gap of 10 years in male life expectancy between the most affluent (North Jesmond) and the most deprived (Walker) wards in the City (Know Newcastle, 2016: 2, using 2011 Census data). There are also strong differences in educational attainments of school age children between the most and least deprived wards (Know Newcastle, 2017). In relation to urban greenspace, Newcastle is relatively well-provided in terms of hectares per capita, but this is not evenly distributed. An immense area of grassland, the Town Moor, centrally situated, accounts for over 20 per cent of the city’s greenspace; while some of the city’s more deprived communities, many in the formerly industrial riverside areas, are both underprovided with greenspace and what they do have comes in smaller parcels (Davoudi and Brooks, 2012: 82-93). Furthermore, a study of greenspace accessibility in the city’s urban core showed a statistical relationship at ward level between a higher score for deprivation on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) and longer average distances to access urban greenspace (Caparros-Midwood, 2011).

Using a different kind of detailed approach in analysis of greenspace distribution, Newcastle City Council’s 2016-2030 Open Space Assessment divided provision into the six major categories of Allotments, Amenity Green Space (that is, open to use but not laid out for specific function), Natural Green Space, Park and Recreation Grounds (including subcategories for fixed outdoor sports spaces and pitches); Children’s Play Space and Play Space for Young People (NCC, 2017a: 57). For each ward, the actual provision of each type of greenspace was compared with national standards for the numbers of hectares recommended per 1,000 population (NCC, 2017a: 82). The resulting comparison of provision against standards identified some important features, such as under-provision of youth facilities in 20 out of the city’s 26 wards. By contrast every ward exceeded the standard for the subcategories of fixed outdoor sports facilities and outdoor pitches.

The consultation also records the high proportion of people who are prepared to undertake journeys of 20 minutes or more to access ‘feature’ green space such as country parks, woodland, nature reserves and water recreation features (NCC, 2016: 12; NCC, 2017a: 46-7). Here, it needs to be borne in mind that those in deprived wards, which have lower levels of car ownership, may have difficulties accessing some of these amenities, due to the limited public transport options providing links between peripheral areas, rather than directly from the periphery to the centre (Davoudi and Brooks, 2012: 115).

As mentioned earlier, a further aspect of distribution concerns the distribution of quality. Studies show that greenspace in the vicinity of deprived communities is less well-maintained and of lower environmental quality. Research in the UK has shown that parks run by local authorities in deprived areas had lower standards of maintenance than parks run by wealthier local authorities (Duffy, 2000). This suggests that greenspace quality is at least in part an issue of resources.

The question of greenspace quality concerns not only how well-maintained and free of litter a public space is, but how accessible it is for people with bodies which deviate from an ideal of adult strength and health. For example, people with mobility aids, or with limited physical stamina, could be effectively excluded from a park by distant entrance points, poor quality surfaces, steps and stairs. Mobility may also be an issue for people with young children.

Another dimension of quality is the design of greenspace, including features such as clear sightlines. Women in particular may be less likely to venture into a space where they do not feel safe (Roman and Chalfin, 2008). The facilities available within greenspace, such as resting points, and public conveniences, also promote or inhibit access for those who depend on such provision (see for example, Williams and Green, 2001).

In Newcastle, an earlier satisfaction survey by the council suggests that it may be possible to discern differences in satisfaction with green space quality between the most deprived and affluent wards. There was a general pattern of lower satisfaction scores (below 70 per cent) in the most deprived wards and higher satisfaction scores (over 80 per cent) in the affluent wards – although there were some exceptions to this pattern (NCC, 2004).

A later public consultation on greenspace was carried out in 2016 as part of the Newcastle City Open Space Study. Although the results were presented in aggregated form, they record high dissatisfaction with the quality of outdoor facilities for teenagers, multi-use games areas, and tennis and netball courts (NCC, 2017a: 46). This is likely to contribute to the cumulative disadvantage suffered by young people in deprived communities, who may have few options for recreation other than public facilities.

Recognition

Recognition is the way we accommodate and respect people with different cultures, knowledge systems and understandings from our own, based on the insight that in any justice claim, some voices, in particular those of the powerful and privileged, will be amplified, while others will be muted or even silenced. Recognition is therefore looking critically at who stands to gain from the imposition of justice as conventionally understood (Martin, 2017).

Valuing recognition as a form of justice does not entail a rejection of distributive justice, but rather an expansion of the justice concept. Scholars such as Nancy Fraser propose a ‘bivalent’ concept of justice which includes ‘both distribution and recognition without reducing either one of them to the other’ (Fraser, 1996: 30). She specifies that the objective condition of justice may be secured by redistribution, but recognition is needed to guard its inter-subjective condition (Fraser, 2003: 36).

There is both a quantitative and a qualitative dimension to recognition. A study by the Commission for Architecture and Built Environment (CABE) identified that there is 11 times less green space in areas where more than 40 per cent of residents are black or of a minority ethnicity than in areas where more than 60 per cent of residents are white (CABE, 2010a: 8). Furthermore, the spaces near to black or minority ethnic communities are mainly of poorer quality (ibid: 8). But quality is not only about ‘qualities in the space’, it includes the ‘qualities of the space’, which we will now explore further (see also Davoudi and Brooks, 2016 for more discussion of this dimension).

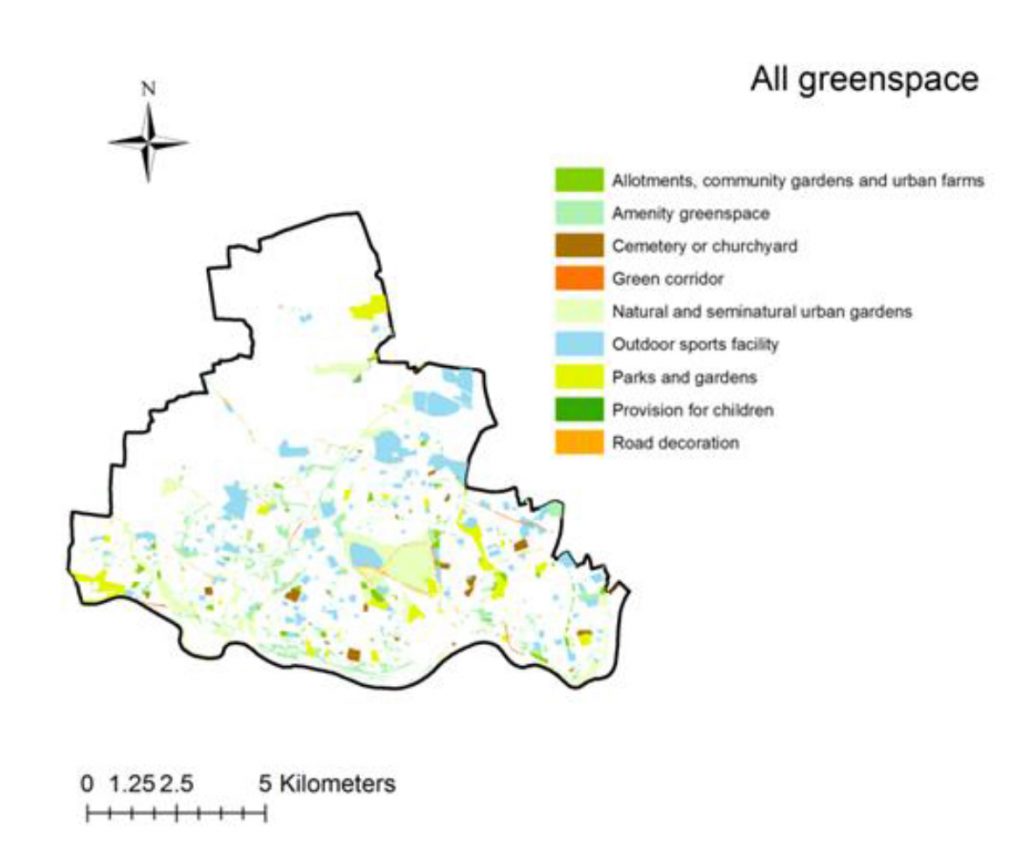

Various studies have shown the high value of green space for first generation migrants, helping to give a sense of connection through aspects such as being able to identify familiar plants from the home country; and particularly for Asian women, being able to use parks as place for gathering and socialising (CABE, 2010b: 15). But some aspects of greenspace have less cross-cultural resonance. Local authorities have been encouraged in government guidance to distinguish between different uses and functions of greenspace, such as parks and recreation areas, amenity greenspace, allotments, cemeteries and urban farms (ODPM, 2002: 2.6-2.7; see also Figure 1, below). All these different kinds of space are counted as part of a Local Authority’s greenspace provision, but there appears to be little awareness of the socio-cultural qualities that inhere in these different kinds of public land and how these might affect access by people of different ethnicities and cultures.

Studies from the US indicate how ethno-racial groups of users are differently repelled or attracted by different qualities in greenspace, thus affecting their likelihood to use the space. For example, Byrne and Wolch (2009) explore the impacts of different ways of perceiving the same greenspace by different groups of users. Ethnic minorities can experience greenspace as either welcoming or discouraging – for example, as a predominantly white space (Byrne and Wolch, 2009: 752). The concept of intersectionality encourages consideration of how multiple categories of belonging can interact in creating a different, rather than cumulative experience (Rosenthal, 2016). Thus, a combination of female gender, minority ethnicity and disability would create a distinctive claim for recognition in relation to greenspace, that could not be assumed to be known just by knowing the needs of the component identities.

Considered separately, age, disability and gender feature strongly in international and national greenspace guidelines, but there remains a blindness to the impact of ethnicity, suggesting that recognition may be a particularly overlooked aspect of environmental justice. For example, one of the 10 targets of the UN’s eleventh Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) (‘Make Cities Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable’) is: “By 2030 provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities” (UN, 2015). This appears on the UK government SDG site as “Average share of the built-up area of cities that is open space for public use for all, by sex, age and persons with disabilities” (ONS, 2018). In both expressions of the Goal, the dimension of ethnicity appears to be absent.

Figure 1 below shows the greenspace in Newcastle by category in 2012 Although there may have been some change in the intervening period, it can be seen clearly from the map that a large proportion of the city’s greenspace is made up of uses such as outdoor sports facilities and cemeteries: uses that may be found unwelcoming or even excluding to some cultures (relating, for example, to the typical clothing and gendered nature of some sports).

The cultural dimension of the qualities in greenspace is all the more salient given the rapidly changing ethnic make-up of the city’s population. Newcastle has the highest number (37,579) as well as population share (13 per cent) of non-UK born residents in the north east region. This was also the authority where the region’s biggest increase in non-UK born population took place, between the 2001 and 2011 census, an increase of 113.5 per cent (The Migration Observatory, 2013).

These figures exclude UK-born ethnic minorities. Newcastle City’s analysis of the 2011 Census data shows that 14.7 per cent of the city’s population were from an ethnic minority in 2011, while the figure was close to 22 per cent for those aged 0-15 (Know Newcastle, 2018, Table 1.11-1). For the whole population, the ethnic make-up of the city was as follows:

- 8 per cent Asian (including Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Chinese and Other Asian);

- 9 per cent Black;

- 6 per cent Mixed and;

- 4 per cent chose the classification of Other ethnic group.

Additional to the 14.7 per cent are the 3.7 per cent of Census respondents who chose the designation White Other (Know Newcastle, 2018: 4).

Combined with the absence of recognition of different cultures and religions in the city in the greenspace consultations undertaken by the Council (see next section), we can conclude that recognition is an overlooked aspect of environmental justice in Newcastle.

Participation

‘Procedural justice’ – defined as the ability of people affected by decisions to participate in making them – is widely recognized as an important aspect of environmental justice (Ottinger, 2013). Fraser (1996) sees participation as the key to combining recognition with redistribution, based upon ‘parity of participation’ in society and fair representation in decision making.

At a national level, the beginning of a more participative approach to the management of greenspace was seen in the various user consultations and surveys that took place around greenspace in the early years of the millennium. These were encouraged by the recommendations around user involvement in the main planning guidance document for greenspace up to the introduction of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in 2012, known as Planning Policy Guidance Note 17 (or PPG 17) (ODPM, 2002).

Initially, such consultations would have taken the form of printed postal surveys, but increasingly the internet consultation and survey has largely taken the place of the old-style paper questionnaire. This has if anything greater limitations, due to differences in modes of engagement with Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in privileged and disadvantaged communities, as discussed in the case of Newcastle below.

Although the practice of involving local people in greenspace maintenance or transformation projects promises a deeper level of engagement, in practice it raises similar issues about inclusion as in consultations. When the local authority stands at arms’ length from such initiatives, the procedures for including disadvantaged communities in the participation may not be clear and the devolution to NGO management can reduce transparency around inclusive processes (HoC CLG, 2017).

Newcastle’s Open Space Assessment included a Community and Stakeholder Consultation Component (NCC, 2016), which surveyed residents about the main categories of the audit: the quantity, quality and accessibility of greenspace in the city. Of 3,000 paper survey forms sent out, 461 were completed. This was supplemented by surveys of parish councils, local groups and organisations, sports’ national governing bodies and local sports clubs (NCC, 2017a: 45). There is nevertheless only one mention of ethnic minority communities in this 108-page document, in reference to the long-term Cycle Strategy for the City (NCC, 2016: 60). Equally only one major religious affiliation is referenced; unsurprisingly, perhaps, this is Christian (ibid: 3).

A larger-scale consultation was undertaken in 2017 with regard to the plans to transfer the management of the city’s major parks and all of its allotments to a charitable trust. Various ways of gathering views were used, both online and offline (NCC, 2017b: 3). This consultation had almost 10 times the response rate of the 2016 consultation and can be assumed to have had greater accessibility for disadvantaged people, through the use of face to face methods such as drop-ins and workshops, which accounted for around 16 per cent of the response.

The consultation report, which runs to over 80 pages, gives a detailed socio-demographic picture of online survey participants, presented as a pie chart. According to this, 94 per cent of survey respondents were White British, with the remaining six per cent composed of two per cent White Irish, I per cent Pakistani and three per cent Other White. Although it appears that different ethnicity categories from those used in the Census were used, the survey response is undoubtedly highly unrepresentative – particularly given that White Irish and White Other are categories not included in the City’s total ethnic minority population of 14.7 per cent in 2011 (as noted in the previous section). It is not clear whether any attempt was made to reach out to the missing ethnic minority groups: sizeable and established minorities as well as smaller ethnic groups are omitted from the report on Newcastle’s greenspace transfer consultation.

Another issue for participation is the digital divide, which although it has continually narrowed in terms of access, may remain a reality in terms of qualitative aspects such as skills, attitudes and types of engagement (ONS, 2017; Helsper, 2012; Clayton and McDonald, 2013). Patterns of internet use may systematically differ between affluent neighbourhoods of Newcastle, found to have pervasive ICT usage, compared with sporadic use in a deprived neighbourhood (Crang et al., 2006). Perhaps, not altogether surprisingly, in the analysis of online survey responses to the recent consultation on the future of Newcastle’s parks the more affluent wards are over-represented as a proportion of respondents, as shown in Table 1 below.

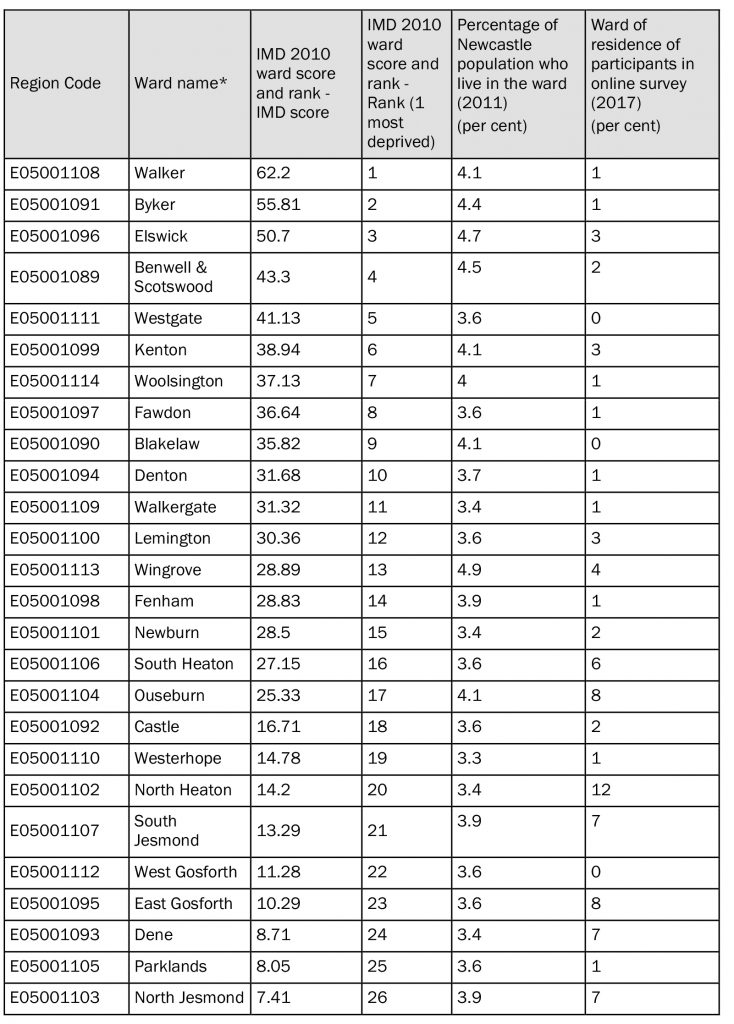

Table 1: Responses to Newcastle’s Future Parks Consultation, by Ward IMD rank

Dataset: Index of Multiple Deprivation 2010 by ward

Source: Data downloaded from Know Newcastle, http://www.knownewcastle.org.uk/ (columns 1-4) and organised by rank; Column 5 added from Newcastle City Council (2017).

* Although ward names and boundaries changed in 2016, the survey analysis uses the previous names of wards.

To summarise Table 1, 21 per cent of responses came from the 50 per cent of wards with higher IMD ranks; which nevertheless in 2011, represented 52.7 per cent of the population. By contrast, the overwhelming majority of responses were from the 50 per cent lower IMD – more affluent – wards. The top 10 most affluent wards accounted for 53 per cent of responses, although comprising only 36 per cent of the city’s population.

Capabilities

Capabilities is about the availability or distribution of opportunities for self-development towards desired goals (Sen, 2009; Nussbaum, 2011). Capabilities refer to the capacity of people to function in the lives they choose for themselves, so it is an approach that is sensitive to human diversity and the different values goods have for different people, at different times of their lives and in different places. A capability approach to justice challenges a focus on the means of living, such as income, on the grounds that it is unable to account for the structural, institutional and cultural factors that affect the conversion of the means of living into: capabilities (substantive, rather than notional, options), functioning (such as breathing clean air, engaging with nature), and well-being driven freedom. There are various options for deciding what these mean in a particular context, but Sen proposes ‘group discussion’ as the best way of selecting, trading off and prioritising capabilities (Crocker, 2008), which links the issue of capabilities back to the issue of participation, discussed above.

Many of the capabilities, functionings and freedoms people seek depend upon the availability and accessibility of public amenities. Increasingly the design of parks and greenspaces acknowledges the importance of options for people to pursue their goals and interests (Barford, 2012; Keep Britain Tidy, 2016). Thus, even with an increased income, if someone lives in an area lacking in accessible greenspace, aims ranging from engaging with the natural world, recuperating from an episode of ill-health, developing horticultural skills or participating in sports can be out of range.

Goals might not only be individual or family-directed but might relate to social interaction and community building. The social capital generated by interaction in greenspace, from a regular football match to an annual fair, can create the foundation for further personal and community development. This can also be seen as aspect of supporting people to exercise their freedom to take responsibility, as discussed in the next section.

Newcastle City Council’s recent Open Spaces Assessment suggests that capabilities in terms of access to sports facilities have the potential to be well-catered for in the city, given that the standard for outdoor sports fixtures and pitches is met or exceeded in every city ward (NCC, 2017a: 82). This apparently impressive achievement is, however, somewhat belied by quality issues with some types of provision (ibid.: 46).

However, the majority of wards (20/26) have deficiencies in the quantity of play space for young people, and more than half do not meet the quantity standard for allotments. Furthermore, a ward-by-ward summary of open space assets and challenges (NCC, 2017a: 100), reveals three wards where there is a deficiency in all the different types of greenspace amenity, and ten where there are shortfalls in a majority of types. There is no clear association with deprivation in the location of deficiency – at least at ward level – a finding which is backed up in other studies (as cited in Kimpton, 2017: 137). However, the focus of environmental justice of greenspace is on cumulative justice impacts of the lack of access to these varied public greenspace amenities on those who are already disadvantaged and thus have fewer options for either travelling to access a distant public amenity, or for the fees demanded by private sports clubs and play facilities.

Both quantitative and quality issues with specialised types of greenspace in some of the deprived wards are likely to limit the capabilities, or capacity to develop in desired directions, of the communities living there. Furthermore, quality issues appear to affect particularly provision for the City’s young people of whom more than one in five are from an ethnic minority.

Responsibility

It is sometimes automatically assumed that people have responsibilities wherever they have rights, but consideration of the unequal distribution of freedoms and capabilities is likely to undermine this assumption. Vulnerable groups and people in poverty may be obliged to devote more of their time to meeting immediate needs that they cannot afford to ‘outsource’. At the same time, the intentionally or unintentionally excluding nature of structures and institutions can constrain people’s ability to take an active part in what concern them, however much they care.

Thus, in cases where there is a lack of greenspace, it is useful to ask to what extent local people have been able to play any role in this – for example, if a brownfield site is sold by the council to developers, has there been any involvement of local people in exploration of alternative uses such as greenspace provision? Where the locally available greenspace is in such a condition as to discourage use, the question is to what extent the local community has contributed to this, and whether have they been able to exercise the option of caring for and improving the space.

In disadvantaged communities, blights of littering, fly-tipping, graffiti, and vandalism can make it appear as though the local people are indifferent to their environment. Poor local environmental quality is cumulative (Ellaway et al., 2009; Keizer et al., 2008; Krauss et al., 1996), and the urban context, facilities and design have an important role to play in local environmental quality, beyond the actions and choices of local people. Furthermore, environmental blight is self-perpetuating, with potential impacts greater than the sum of its parts (Brook Lyndhurst, 2012; Keep Britain Tidy, 2014: 27). Once it is has taken hold of an amenity, such as a park, it is likely that a multi-faceted programme for remediation will be required to reverse the damage. The participation of local people in such a process could inform understanding of the causes of the decline, while generating solutions that are workable in the social context of the park, and acceptable to the park’s users.

There is growing awareness of the vulnerability of the natural world and the rise in threatened species and species extinction. Having the freedom to take responsibility for the quality of the local environment may be particularly salient in a governance context where the negative externalities of transport, retail and food industries are under-legislated.

Even in Newcastle, it is not impossible to retro-add natural space to an urban context. For example, in Walker, the city’s most deprived ward in 2010, a former riverside leadworks was converted to parkland. However, because of the extremely high level of lead contamination in the soil, it was planted as dense woodland which is fenced off to prevent accidental harm. The deprived community of Walker appears to have had little input into the conversion of this site, which is adjacent to the Hadrian’s Wall Path in Walker Riverside Park, and potentially detracts from the security of that path in closing off sightlines between the path and nearby housing (Davoudi and Brooks, 2012). By contrast, in the middle-range IMD ward of Wingrove, local residents participated in creating strategies to make better use of trees and plants, while paying attention to co-benefits including savings on energy bills. The ‘Greening Wingrove’ project also encouraged residents to come up with new ways to improve their local environment (NCC, 2011: 15).

In an example that may provide useful learning in the current context of management transfer of the City’s main parks and all its allotments to a charitable body, the Groundwork Trust brought its approach to supporting deprived communities to take control of their local parks and open spaces (Fordham et al., 2002) to renovations and improvements to over 40 Newcastle parks, open spaces and school grounds. Of these projects, 15 created Green Gyms, which included outdoor exercise equipment for all – not just for children (NCC, 2012: 27).

Challenges to the centrality of distribution in environmental justice

The approach to auditing greenspace proposed in Planning Policy Guidance 17 (explained further in ODPM, 2004) and its successor planning documents, the National Planning Policy Framework (CLG, 2012: points 73 and 74 and in the revised 2018 version points 95 and 96), defaults to the distribution of greenspace as the central element. A capabilities dimension is added to such audits by considering access to the various subtypes of greenspace such as open-air sports facilities and playing fields, cycling tracks and outdoor gym equipment. Although such audits undoubtedly furnish a useful baseline for action plans, the quantitative focus can underestimate the impact on accessibility of the physical and cultural qualities of a space.

The case has been made for placing another dimension at the heart of environmental justice, that is, the concept of recognition (e.g. Bulkeley et al., 2014). This is likely to apply particularly where a government that represents one model of knowledge, culture and understanding in a society exercises power over the environmental resources of a group or groups with different or opposing ways of conceiving, knowing and living with the natural world – a situation that increasingly arises in relation to conservation and resource exploitation (Martin et al., 2016; Kennedy et al., 2017). It may also be highly relevant to greenspace.

An alternative approach that is able to capture all of the core elements might be to consider the element of participation as the central dimension to the environmental justice of greenspace. A continuing participation process can conceivably be designed that explicitly interrogates and foregrounds who currently feels excluded from the greenspace (recognition); how the greenspace could help people to fulfil their personal goals, in particular those who cannot afford to access private alternatives (capabilities), and what role people want to have in the creation, design and maintenance of the greenspace (responsibility).

Which, if any, of the EJ dimensions is chosen as pivotal must ultimately depend on context. In specific places, or in light of particular historical developments, there might be good reason to privilege one element over all the others.

Greenspace management transfer and environmental justice

Austerity measures have continued to erode local government funding and as provision of greenspace is not a statutory obligation upon authorities, it has been increasingly under threat in many cash-strapped local authority areas. Newcastle alone lost over 90 per cent of its budget for parks in the seven years since 2011 (NCC, 2018). Although the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) helpfully responded with substantial investment through its Parks for People programme, the programme was limited to capital funding and entailed conditions for upkeep (HoC CLG, 2017: 37). Furthermore, all HLF targeted programmes were closed in 2018, so now parks must compete with other applicants in open calls.

Responses to the crunch on funds for greenspace have been various. In some authorities, parts of the local authority greenspace provision have been sold off to developers in an attempt to save the council the cost of their management; and/or to raise revenues to support other areas of council activity. In at least one case (Liverpool) this has been prevented by local protests and alternative options including a transfer to a community ownership organisation has taken place. Newcastle can be said to have a venerable history of parks that contribute to their own upkeep: the large natural greenspace area at the centre of the city, the Town Moor, dates back to the twelfth century and generates a rental income from grazing. Furthermore, various longstanding parks events, such as the historical annual Hoppings fair on the Moor, may have accustomed local people to seeing time-limited commercial activities within the city’s greenspace.

By the end of 2018, as mentioned earlier, the management of 33 of the city’s parks and all of its allotments will be leased to a charitable trust, the first of its kind in the UK. In May 2018 the newly-created post of Chief Executive for Newcastle Parks Trust was advertised by charities recruitment agency Harris Hill at a salary of £75,000 per annum. The Job Summary for the new post notes that:

the Council is creating a new independent charity: the Newcastle Parks Trust, which will unlock new sources of funding that can protect Newcastle’s parks and allotments for future generations; transform their contribution to communities; achieve expenditure efficiencies; ring-fence and recycle income purely for the benefit of parks; and involve local people in shaping the future of their green spaces. (The Guardian, 2018)

The fact the city is not transferring ownership, but only management, of the greenspace, which it can retract if dissatisfied with the result, allows some degree of assurance that the new charity should operate in conformity with the norms of responsible public service delivery. Furthermore, the involvement of a large national body, in the form of the National Trust, which is a partner within the new organisation, can to some degree guard against the challenges of parochialism that can threaten effective devolution of powers to a lower scale (Madanipour and Davoudi, 2015).

But as we have already seen, the Council has not shown a clear awareness of what constitutes representativeness and inclusiveness with regard to public consultation on greenspace, so the question must arise of whether a charitable body will be able to set itself a higher standard for public participation when it comes to meet the standard set out in the job advertisement of: ‘ a vibrant future for its parks as […] spaces, where people of all ages and backgrounds can enjoy moments of tranquillity or join in activities that are open to all; destination venues, drawing in people from across the city and beyond’ (The Guardian, 2018).

The reference to people from beyond the city is worth considering in the light of the spatial bounds of environmental justice. How would local people respond to a situation where some parks become self-sustaining through major events and festivals with a regional and national appeal? Journalistic accounts of the monetization of parks suggest the potential for antagonism between local people’s wishes for tranquillity and disruptive, noisy events, and this is anticipated by many responses to the council’s survey (NCC, 2017b: 31). There is also a risk that over time the design of a park may be adapted to attract a particular commercial use or uses. Eventually, a park’s purpose may even shift from being a public good to a profit-seeking asset; one that earns its own upkeep by offering a green backdrop to various exclusive business activities. To what extent is it still possible to reserve greenspace amenities for the benefit of local people when a large proportion of the revenues for their upkeep are not channelled through the local authority?

For these reasons, in the context of greenspace in Newcastle upon Tyne, the quality of public participation in the new management body and in its interaction with local communities is likely to emerge as pivotal for environmental justice. Participation is central not only because it paves the way for the justice of recognition and fosters awareness of parks’ role in developing capabilities, but because it takes advantage of a major benefit of the new management arrangement, in allowing more people to become involved and take responsibility for their environment, both human and natural.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have reviewed a pluralistic framework of environmental justice, developed for a study of environmental burdens and benefits in Newcastle upon Tyne, and updated its application to greenspace in the city, with a focus on the recent transfer of the city’s parks and allotments to management by a charitable body.

At a theoretical level, reviewing the multi-dimensional framework has drawn out the interdependencies between the five EJ elements, and provided insights into how, in certain contexts, a dimension such as recognition or participation can become centrally pivotal to greenspace justice – challenging the default assumption, made by national and local authorities, that distribution is invariably the main consideration.

There is no doubt that distribution is important: in encouraging greater scrutiny of the city-wide distributive deficiencies in specific types of greenspace, as identified by local authority’s audit, the EJ perspective used in this paper indicates the existence of cumulative disadvantage. While deficiencies such as the ward-by-ward provision of allotments and of play spaces for young people cannot be shown precisely to map onto the areas of deprivation in the city, an overall low level of provision implies a particular disadvantage to those in deprived communities and wards, given that they are less likely to be able to access private alternatives.

Exploring how environmental justice plays out in a particular city’s provision of greenspace has also allowed a deeper understanding of the value of a range of different types of greenspace for disadvantaged communities, who may not be able to access and/or afford private alternatives. These benefits run from the equigenic health impacts identified in the section on distribution, to the opportunities explored in the sections on capabilities and responsibility for self-development, nature care, social-network building and community development.

In Newcastle, recognition of the city’s ethnic minorities has emerged as poor, reflecting a similar weakness in both national and international greenspace policy. The published reports on recent greenspace consultations in Newcastle reveal a lack of attention to the city’s rising ethnic minority population. In its most recent survey, the council’s use of alternative methods beyond an online survey in their consultation suggest awareness of the need to bridge the digital divide and bring in those who by choice or necessity, favour face-to-face methods. However, the lack of information on how successful these methods were in reaching the ethnic minority groups under-represented through the surveys, alongside the absence of an account of the actual ethnic composition of the city’s population, effectively mutes their voice and views. The lack of recognition was at the time of writing also reflected in the Council’s main public interface, its website. A future research study might usefully explore recognition in greenspace governance, as well as in overall governance, in the city.

While recognition is important, participation can also include recognition and so we identify it as the central plank of current and future greenspace environmental justice in Newcastle. To achieve the Newcastle Parks Trust’s stated ambition to ‘involve local people in shaping the future of their greenspaces’ requires that explicit recognition of different and under-included voices is accompanied by the understanding that greenspace is of far greater importance for deprived and disadvantaged communities than for their privileged counterparts. A future research study exploring whether devolution to charitable trust management in Newcastle has achieved greater or lesser inclusiveness in greenspace processes would be useful in this regard. If the free and public nature of city greenspace is not to be curtailed in favour of commerce and city marketing, a central role must be given to those for whom local green places are the main or only play grounds, gardens, sports and social centres.

Dr Elizabeth Brooks, School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, 3.01, Claremont Tower, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU.

Agyeman, J. and Warner, K. (2002) Putting ‘just sustainability’ into place: from paradigm to practice. Policy and Management Review, 2, 1, 8-40.

Barford, V. (2012) What makes a quintessentially British park? BBC News Magazine, [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-20710917 [Accessed: 12/05/2018]

Benford, R. (2005) The half-life of the environmental justice frame: Innovation, diffusion and stagnation. In: Pellow, D.N. and Brulle, R.J. (eds) Power, Justice and the Environment: A Critical Appraisal of the Environmental Justice Movement. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 37-54.

Bird, W. (2004) Natural Fit: Can Greenspace and Biodiversity Increase Levels of Physical Activity? Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

Brook Lyndhurst (2012) Evidence review of littering behaviour and anti-litter policies. Stirling: Zero Waste Scotland.

Brooks E. and Davoudi S. (2017) ‘Litter and social practices.’ Journal of Litter and Local Environmental Quality, 1, 1, 16-25.

Bulkeley, H., Edwards, G.A.S. and Fuller, S. (2014) Contesting climate justice in the city: examining politics and practice in urban climate change experiments. Global Environmental Change, 24, 31-40. CrossRef link

Bullard, R. (1990) Dumping in Dixie: Race, class and environmental quality. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Byrne, J. and Wolch, J. (2009) Nature, race and parks: past research and future directions for geographic research. Progress in Human Geography, 33, 743-65. CrossRef link

CABE (2008) Paying for Parks: eight models for funding urban greenspaces. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110118111034/http://

www.cabe.org.uk/files/paying-for-parks.pdf [Accessed: 15/06/2018]

CABE (2010a) Urban green nation: building the evidence base. London: CABE.

CABE (2010b) Community green: using local spaces to tackle inequality and improve health. London: CABE.

Caparros-Midwood, D. (2011) A GIS investigation of the relationship between urban greenspace and the socio-demographic of a city. Unpublished BSc thesis. Newcastle upon Tyne: University of Newcastle.

Clayton, J. and McDonald, S. (2013) The limits of technology: social class, occupation and digital inclusion in the city of Sunderland, England. Information, Communication and Society, 16, 945–66. CrossRef link

Communities and Local Government (2012) ‘National Planning Policy Framework’. London: CLG.

Communities and Local Government (2018) ‘National Planning Policy Framework’. London: CLG.

Crang, M., Graham, S. and Crosbie, T. (2006) Variable geometries of connection: urban digital divides and the uses of information technology. Urban Studies, 43, 2551–70. CrossRef link

Crocker, D. (2008) Ethics of global development: agency, capability and deliberative democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. CrossRef link

CSD (2011) Understanding the contribution parks and green spaces can make to improving people’s lives. London: Chartered Society of Designers.

Cutter, S. (1995) The forgotten casualties: Women, children and environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 5, 3, 181–194. CrossRef link

Davoudi, S. and Brooks, E. (2012) Environmental Justice and the City: Full Report. Newcastle: GURU Publications. Available at: https://www.ncl.ac.uk/media/wwwnclacuk/socialrenewal/files/environmental-justice-and-the-city-final.pdf [Accessed: 12/05/2018] CrossRef link

Davoudi, S. and Brooks, E. (2016) Urban greenspace and environmental justice claims. In: Bell D. and Davoudi S. (eds) Justice and Fairness in the City. Policy Press: Bristol, 25-47.

De Sousa, C. (2004) The greening of brownfields in American cities. The Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 47, 4, 579-600. CrossRef link

Duffy, B. (2000) Satisfaction and Expectations: attitudes to public services in deprived areas. CASE Paper 45. London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion.

Ellaway, A., Morris, G., Curtice, J., Robertson, C., Allardice, G. and Robertson, R. (2009) Associations between health and different kinds of environmental incivility: a Scotland-wide study. Public Health, 123, 708-713. CrossRef link

Evans, J. (2015) A green workspace in the city: but will the office treehouse catch on? The Guardian, [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jun/11/a-green-workspace-in-the-city-but-will-the-treehouse-office-catch-on [Accessed: 22/05/2018]

Fordham, G., Gore, T., Knight-Fordham, R. and Lawless, P. (2002) The Groundwork Movement: its role in neighbourhood renewal. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation/York Publishing Services.

Fraser, N. (1996) Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, Recognition, and Participation. Stanford University: The Tanner Lectures. Available at: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/

12624/ssoar-1998-fraser-social_justice_in_the_age.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed: 20/05/2018]

Fraser, N. (2003) Social justice in the age of identity politics: redistribution, recognition, and participation. In: Fraser, N. and Honneth, A. (eds) Redistribution or recognition? A political–philosophical exchange. New York: Verso, 7–109.

Future Parks (2018) Newcastle Story: Planning for Implementation, [online]. Available at: http://www.futureparks.org/toolkit/planning-implementation [Accessed: 30/04/2018]

Goldman, B.A. (1996) What is the future of environmental justice? Antipode, 28, 2,122-141. CrossRef link

UK Government (2016) Green light given to over 80 pocket parks, [online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/green-light-given-to-over-80-pocket-parks. [Accessed: 04/04/2018]

Helsper, E. (2012) A corresponding fields model for the links between social and digital exclusion. Communication Theory, 22, 403–26. CrossRef link

Heritage Lottery Fund (2016) State of UK Public Parks 2016. London: HLF.

Heynen, N., Perkins, H.A. and Roy, P. (2006) The political ecology of uneven urban greenspace: the impact of political economy on race and ethnicity in producing environmental inequality in Milwaukee. Urban Affairs Review, 42, 3–25. CrossRef link

House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee (2017) Public Parks. Seventh Report of Session 2016-17. HC 45. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmcomloc/45/45.pdf. [Accessed: 12/05/2018]

Kennedy, A., Schafft, K.A., and Howard, T.M. (2017) Taking away David’s sling: environmental justice and land-use conflict in extractive resource development. Local Environment, 22, 8, 952-968. CrossRef link

Keep Britain Tidy (2014) How clean is England? The Local Environmental Quality Survey of England 2013/14. November, London: Keep Britain Tidy.

Keep Britain Tidy (2016) Celebrating Amazing Spaces: Green Flag Award. Wigan: Keep Britain Tidy.

Keizer, K., Lindenberg, S. and Steg, L. (2008) The spreading of disorder. Science, 322 1681–1685. CrossRef link

Kimpton, A (2017) A spatial analytic approach for classifying greenspace and comparing greenspace social equity. Applied Geography, 82, 129-142. CrossRef link

Know Newcastle (2016) 3.4: End of Life. Available at: https://www.wellbeingforlife.org.uk/sites/default/files/3%204%20End%20of%20life%20Jan%2016.pdf. [Accessed: 08/05/2018]

Know Newcastle (2017) ‘2.5: Activities’. Available at: https://www.wellbeingforlife.org.uk/sites/default/files/2.5%20Activities%20-%20May%2017.pdf [Accessed: 08/05/2018]

Know Newcastle (2018) ‘Know Your City: The People Living, Working and Learning in Newcastle’ Part B, [online]. Available at: http://www.knownewcastle.org.uk/GroupPage.aspx?GroupID=62 [Accessed: 21/05/2018]

Krauss, M., Freedman, J. and Whitcup, M. (1996) Field and laboratory studies of littering. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 14, 109-122. CrossRef link

Lucas, K., Walker, G., Eames, M., Hay, F. and Poustie, M. (2004) Environment and social justice review: rapid research and evidence review, revised version, December 2004. London: Policy Studies Institute.

Madanipour, A. and Davoudi, S. (2015) Localism: Institutions, Territories, Representations. In: Reconsidering Localism. Abingdon: Routledge, 11-29. CrossRef link

Marmot, M. (2010) The Marmot Review: fair society, healthy lives. London: UCL.

Martin, A (2017) Just Conservation: Biodiversity, Wellbeing and Sustainability. London: Routledge. CrossRef link

Martin, A., Coolsaet, B., Corbera, E., Dawson, N.M., Fraser, J.A., Lehmann, I. and Rodriguez, I., (2016) ‘Justice and conservation: the need to incorporate recognition’. Biological Conservation, 197, 254-261. CrossRef link

Mitchell, R and Popham, F (2008) Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: an observational population study. The Lancet, 372, 1655-60. CrossRef link

Mitchell, R, Richardson, E, Shortt, N and Pearce, J (2015) Neighbourhood environments and socio-economic inequalities in mental wellbeing. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 49, 1, 80-84. CrossRef link

Moore, R. (2017) The end of parklife as we know it? The battle for Britain’s green spaces. The Guardian, [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jul/09/the-end-of-park-life-as-we-know-it-the-battle-for-britains-green-spaces-rowan-moore [Accessed: 20/05/2018]

National Audit Office (NAO) (2014) The impact of funding reductions on local authorities. London: NAO. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/the-impact-funding-reductions-local-authorities/ [Accessed: 05/05/2018]

Nesta, Heritage Lottery Fund and The Lottery Fund (2016) Learning to Rethink Parks. London: Nesta/HLF/TLF. Available at: https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/learning_to_rethinking_parks_report.pdf [Accessed 14/04/2018]

Newcastle City Council (2004) Greenspaces, your spaces: Newcastle’s greenspace strategy. Newcastle: Newcastle City Council.

Newcastle City Council (2011) Residents’ survey 2010/2011 report on wards results. Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle City Council, Chief executive Directorate.

Newcastle City Council (2012) Green Capital Bid to the European Commission. Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle City Council.

Newcastle City Council (2016) Newcastle City Council Open Space Study: Community and Stakeholder Consultation – Final. Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle City Council.

Newcastle City Council (2017a) Open Space Assessment: 2016-2030. Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle City Council. Available at: https://www.newcastle.gov.uk/sites/default/files/wwwfileroot/planning-and-buildings/planning-policy/newcastle_city_open_space_study.pdf [Accessed on 17/05/ 2018]

Newcastle City Council (2017b) The Future of Newcastle’s Parks and Allotments: Consultation Report. [online] Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle City Council. Available at: https://www.newcastle.gov.uk/sites/default/files/wwwfileroot/libraries-and-leisure/parks-and-countryside/2017_parks_consultation_report.pdf [Accessed 10/06/2018]

Nussbaum, M. (2011) Creating capabilities: the human development approach. Cambridge MA: Bellknap Press. CrossRef link

ODPM (2002) Planning for Open Space, Sport and Recreation: Planning Policy Guidance 17. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120920011634/http://www.communities.gov.uk/archived/publications/planningandbuilding/planningpolicyguidance17 [Accessed: 20/05/2018]

ODPM (2004) Assessing Needs and Opportunities: A Companion Guide to PPG17. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/7660/156780.pdf [Accessed: 11/5/2018]

ONS (2017) Statistical bulletin: internet access, households and individuals, 2017. Newport: Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/bulletins/internetaccesshouseholdsandindividuals/2017 [Accessed: 07/06/2018]

ONS (2018) Sustainable Development Goals: 11 – Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. Newport: Office for National Statistics [online]. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment-uk.github.io/sustainable-cities-communities [Accessed: 04/04/2018]

Ottinger, G. (2013) Changing Knowledge, Local Knowledge, and Knowledge Gaps: STS Insights into Procedural Justice. Science, Technology and Human Values, Special Issue: Entanglements of Science, Ethics, and Justice, 38, 2, 250-270. CrossRef link

Owen, P. (2008) New York’s historic elevated train line becomes a park. The Guardian [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2008/nov/18/new-york-high-line-park. [Accessed: 12/05/2018]

Panduro, T.E. and Veie, K.L. (2013) Classification and valuation of urban green spaces: a hedonic house price valuation. Land Use and Urban Planning, 120,119-128. CrossRef link

Roman, C. and Chalfin, A. (2008) Fear of walking outdoors: a multilevel environmental analysis. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 34, 4, 306-12. CrossRef link

Rosenthal, L. (2016) Incorporating Intersectionality Into Psychology: An Opportunity to Promote Social Justice and Equity. American Psychologist, 71, 6, 474-485. CrossRef link

Sen, A. (2009) The idea of justice. Harmandsworth, Middx: Penguin.

Taylor, D. (2002) The rise of the environmental justice paradigm: injustice framing and the social construction of environmental discourses. American Behavioral Scientist, 43, 4, 508-80. CrossRef link

The Guardian (2018) Newcastle Parks Trust: Chief Executive, [online]. Available at: https://jobs.theguardian.com/job/6723448/chief-executive/ [Accessed: 02/06/2018]

The Migration Observatory (2013) Briefing: North East Census Profile. Available at: http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/north-east-census-profile/ [Accessed: 15/5/2018]

UCC (United Church of Christ) (1987) Toxic Waste and race in the United States: A national report on the racial and socio-economic characteristics of communities with hazardous waste sites. New York: UCC Commission for Racial Justice.

UK National Ecosystem Assessment (2011) The UK National Ecosystem Assessment: Technical Report. Cambridge: UNEP-WCMC.

United Nations (2015) 17 Goals to Transform Our World: 11 – Cities [online] Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/. [Accessed: 04/04/2018]

US Environmental Protection Agency (2012) Creating Equitable, Healthy and Sustainable Communities: Strategies for Advancing Smart Growth, Environmental Justice and Sustainable Development. Washington: US Environmental Protection Agency. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/creating-equitable-healthy-and-sustainable-communities [Accessed: 10/05/2018]

Voicu, I. and Been, V. (2008) The effect of community gardens on neighboring property values. Real Estate Economics, 36, 241–283. CrossRef link

Walker, G. (2009) Beyond Distribution and Proximity: Exploring the Multiple Spatialities of Environmental Justice. Antipode, 41, 4, 614–636. CrossRef link

Ward Thompson, C., Aspinall, P., Roe, J., Robertson, L. and Miller, D. (2016) Mitigating Stress and Supporting Health in Deprived Urban Communities: The Importance of Green Space and the Social Environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13, 440. CrossRef link

Weinstein, N., Balmford, A., Dehaan, C., Gladwell, V., Bradbury, R. and Amano, T. (2015) Seeing Community for the Trees: The Links among Contact with Natural Environments, Community Cohesion, and Crime. Bioscience, 65, 12, 1141-1153. CrossRef link

White, M. P., Alcock, I. Wheeler, B.W. and Depledge, M.H. (2013) Would You Be Happier Living in a Greener Urban Area? A Fixed-Effects Analysis of Panel Data. Psychological Science, 24, 6, 920-928. CrossRef link

Williams, K. and Green, S. (2001) Literature review of public space and local environments for the cross-cutting review. Oxford: Oxford Brookes University/DTLR.

Zelenski, J.M., Dopko, R.L., Capaldi, C.A. (2015) Cooperation is in our nature: Nature exposure may promote cooperative and environmentally sustainable behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 42, 24–31.