Abstract

This Alternatives paper explores the changing dynamics of town/gown relationships in modern Britain. It argues that there are major opportunities for improving collaboration between universities and ‘off campus’ actors, opportunities that could benefit all concerned. In the past the typical European university saw itself as a cloistered realm, it tended to turn its back on the city. In the 19th century American public universities pioneered a new vision of higher education, one that sought to fuse scholarly inspiration with a strong commitment to practical application. The paper argues that, while some British universities now see themselves as civic universities and many talk of being committed to public engagement, few can claim to be world leading in this regard. Real progress on this agenda can, however, be made if universities explore how to develop their role as influential place-based leaders. To succeed in efforts of this kind universities will need to look afresh at the meaning of modern scholarship, possibly redefining it, and they will also need to consider how they reward academic endeavour. By drawing on the experience of engaged scholarship in other countries the paper closes with some specific policy suggestions on how to rouse the sleeping giants of place-based leadership.

Universities and cities – harmony or discord?

Conventional wisdom tells us that any city or locality that is lucky enough to have a university has a major advantage. This is because a university brings significant economic, social, cultural and intellectual benefits to the area where it is located. There is, to be sure, solid evidence to back this claim (Bothwell, 2017; Goddard and Vallance, 2013).

However, academics, policy makers and activists interested to advance the cause of justice in society might wish to go beyond this generalisation and ask a more pertinent question: ‘Major advantage for whom?’

New research carried out by the UK Centre for Cities shows, for example, that Cambridge has established a solid lead as top of Britain’s most unequal cities league (Centre for Cities, 2018). For the second year in a row Cambridge has pushed Oxford into second place in the unequal cities rankings. This research evidence should provide a wake-up call, not just for the Vice Chancellors of these two universities, but also for all of us who work in or with UK higher education.

In this short Alternatives paper I aim to prompt fresh thinking about the modern role and purpose of a university. More specifically I will explore how to strengthen collaboration between scholars, students and ‘off campus’ actors. The evidence suggests that British universities are becoming more involved in local action/research and problem solving, and this is encouraging. However, the gist of this provocation is that they could be doing much more.

Challenging the cloistered realm?

Traditionally minded scholars, by which I mean those who tend to view the university as a cloistered realm, one that is detached from the realities of societal stresses and strains, will be unconcerned by the Centre for Cities findings.

They will argue that universities should continue to concentrate on advancing knowledge and teaching students – the traditional aims of the European university. The place-based impact of the university on ‘off campus’ neighbours should, from their perspective, not feature in calculations of scholarly purpose.

The Americans recognised that this was an out of date view of academic endeavour over 150 years ago. In 1862, Abraham Lincoln signed into US law the famous Morrill Act. This heralded, not just a startling expansion of higher education in the US, but also a reframing of the very purpose of a university.

In essence, the legislation lead to the establishment in every US state of a distinctively American kind of public university, one that attempted to fuse scholarly inspiration with a strong commitment to practical application (Rhodes, 2001). The US continues to benefit from the remarkable foresight shown by Representative Justin Morrill and his colleagues as the vision he espoused was of an ‘engaged university’, not an ivory tower.

Universities: from anchor institutions to rooted institutions

Most UK universities now recognise that they are not just important academic institutions in their own right, but also, potentially at least, important ‘anchor institutions’ capable of exercising influential place-based leadership (Brink, 2018). Invented in the US, the term anchor institution refers, in essence, to a significant non-profit institution in an area, one that brings socio-economic and cultural benefits to the local community (Birch et al, 2013). The most common examples are universities and hospitals, or ‘eds and meds’ to use a catchy American expression.

Anchor institutions can, if they wish, play a positive and dynamic role in working with local stakeholders to co-create activities that are of shared value. It may, in fact, be time to ditch the term ‘anchor institution’ and replace it with the term ‘rooted institution’. After all, ship captains can weigh anchor and sail away more or less any time they choose.

True, any given university may well decide to extend its reach by building another campus, even a campus in another country. But universities, unlike big business corporations, are not going to ‘up sticks’ and relocate elsewhere. The university is, then, an institution rooted in place, and this is a major reason why it can act as a truly powerful place-based leader and, incidentally, why it can prove so attractive to philanthropic donors.

From 2002-07, I was Dean of the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), a large public university located in the heart of the metropolis. The university has seen itself as an important rooted institution in Chicago for at least 25 years. In 1993, then UIC Chancellor, James Stukel, launched the Great Cities Initiative to join UIC teaching and research with community, government and corporate partners in tackling urban challenges. In 2003, the initiative was, at its ten-year mark, renamed the UIC Great Cities Commitment.

UIC is not the only ‘engaged campus’ in the US. On the contrary many American universities, particularly the major public universities, have been making a significant contribution to place-based leadership in the cities where they are located for decades.1 It is encouraging to be able to record that the ‘engaged campus’ movement is, at last, making firm landfall in the UK (Hambleton, 2016). The evidence to support this claim is widespread, but three national efforts signal a shift towards ‘engaged scholarship’ in British higher education.

First, the UK National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE) now celebrates its tenth birthday. Launched in 2008, the Centre has done much to enlighten thinking relating to engaged scholarship within British universities, and has a great website for academics interested in making a local impact.2

Second, launched in 2016 the Leading Places initiative led by the Local Government Association (LGA), and supported by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), set out to strengthen collaborative leadership between universities and other socially committed public agencies.3

Third, earlier this year, the University Partnerships Programme (UPP) Foundation launched a Civic University Commission in an effort to lift the quality of debate relating to what universities are for and, more specifically, to address how universities might balance an international focus – on both students and research – with playing a much more active role close to home.4

There is a counter argument to the ‘engaged campus’ movement. McLennan (2008) offers a particularly trenchant critique. In essence he claims that ‘engagement talk’ is intellectually flaccid and that its implied progressiveness is questionable. He asks, for example, who is it that we are engaging with, and to what end? His argument should give us pause for thought.

Place-based leadership versus place-less power

In the era of globalisation place-less leaders, that is, people who are not expected to care about the consequences of their decisions for particular places and communities, have gained extraordinary power and influence. Senior figures in multinational companies, by exercising place-less power, decide whether or not particular localities prosper or collapse (Ranney, 2003).

The forces of economic globalisation, which have resulted in a remarkable growth in the number of multinational companies operating on a global basis, have provided the engine for this expansion in place-less policy making, and the consequences for social, economic and environmental justice have been dire (Piketty, 2014; Stiglitz, 2012). In contrast to place-less leaders those who lead anchor, or rooted, institutions are place-based in the sense that they and their staff care about ‘their’ place and, as outlined earlier, they are not going anywhere else.

In my recent book I offer a comparative analysis of outgoing place-based leadership in different cities in fourteen different countries (Hambleton, 2015). The evidence shows, not just that progressive place-based leadership is taking on place-less power in a variety of successful ways, but that, in many cities, universities are playing a critical role in asserting the power of place.

McLennan (2008) is surely right to argue that there is no point in universities trying to appear to be ‘relevant’. Rather, the enlightened university works with local stakeholders to throw new light on who is losing and who is gaining in modern systems of governance. Put simply universities can either serve powerful vested interests or bring a critical eye to processes that are driving inequality in our society. This insight has major implications for the changing nature of modern scholarship.

Scholarship reconsidered

In 1990, Ernest Boyer, President of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, wrote an enormously influential report on the changing nature of modern scholarship (Boyer, 1990). His imaginative exploration of new conceptions of scholarship is highly relevant today. In essence, Boyer argued that it was time:

… to move beyond the tired old “teaching versus research” debate and give the familiar and honourable term “scholarship” a broader, more capacious meaning, one that brings legitimacy to the full scope of academic work. (Boyer, 1990 p16)

Boyer distinguishes four overlapping kinds of scholarship:

- The scholarship of discovery comes closest to what is meant when academics speak of research. It contributes not only to the stock of human knowledge but also to the intellectual climate of a college or university.

- The scholarship of integration gives meaning to isolated facts, putting them in perspective. It places discoveries into their larger scientific, social and political context. It is serious disciplined work that seeks to interpret, draw together, and bring new insights to bear on original research.

- The scholarship of application applies knowledge to consequential problems. Boyer does not see this as a one-way process in which knowledge is first ‘discovered’ and then ‘applied’. He stresses that new intellectual understandings can arise from the very act of application.

- The scholarship of teaching keeps the flame of scholarship alive by sharing knowledge not just with students in the lecture theatre or seminar room but also by disseminating insights and research findings in the public sphere.

Boyer stresses that what we urgently need today is a more inclusive view of what it means to be a scholar: ‘… a recognition that knowledge is acquired through research, through synthesis, through practice, and through teaching’ (Boyer, 1990: 24).

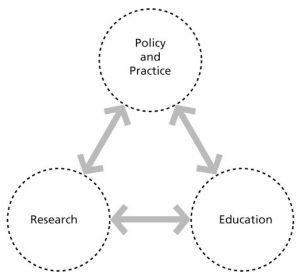

By building on Boyer’s analysis, and my own experience of working in British and American universities, I have advanced the notion of a ‘triangle of engaged scholarship’ (Hambleton, 2007). In this model the familiar pillars of research and education, long established in the European tradition, are linked to a third pillar: policy and practice. This conceptualization is shown in Figure 1.

It is my contention that it is the sides of the triangle that hold out exciting possibilities for intellectual and practical advance. Along the bottom side of the triangle we find the long-established practice, found in all universities, of academics feeding insights drawn from research into course content and exchanges with students.

Turning to the right hand side of the triangle, well-managed student projects can benefit policy and practice in a city or locality as well as enhance the learning experience of the students involved (Hoyt, 2013). There is much good practice in this expanding area, although it is clear that collaborative efforts of this kind can, at times, fail to deliver sufficient benefits for ‘off campus’ actors (Winkler, 2013).

Finally, turning, to the left hand side of the triangle it is here that universities can make major strides forward by working with local stakeholders to co-create new knowledge and discover new possibilities. This is now an area that is expanding rapidly in UK higher education. Research reports emanating from, for example, the UK Connecting Communities Programme offer detailed recommendations to help boost these efforts (Facer and Enright, 2016; Braginskaia and Facer, 2017).

Policy propositions

It can be claimed that UK universities are making a significant contribution to the quality of life in the area where they are located. In more than a few cases they are actively collaborating with other local stakeholders to address local challenges, including how to redress the growth of inequality within society.

However, the argument presented in this article is that, much of the time, university efforts at civic engagement and community collaboration are fragmented and chaotic. Worse than that, in some localities, universities now seem to have strained, even conflictual, relationships with the local population. Less well off groups in society may even feel that the very presence of the university in their area damages their local quality of life because the university acts in a narrowly self-interested way.

What is to be done? By drawing on inspirational practice in other countries, as well as recent research in the UK, I offer three suggestions to stimulate fresh thinking and practice.

First, the UK research councils should create major, new, national funding streams to support community partners and academics to co-create place-based, action/research projects that lead to significant societal benefits at the local level, as well as generating world-leading research insights. To ensure genuine collaboration in the co-creation of research design such funding should only be made available to those universities (and their partners) that are able to demonstrate that they have created solid institutional structures and processes capable of delivering engaged scholarship.

Second, universities should consider not just radical steps to make their research findings more readily accessible to local stakeholders and the public at large, but also how to become much more outgoing in their teaching, research and engagement activities. In essence, they should consider how to enhance their place-based leadership skills at all levels, as well as how to extend and develop ways of embedding action/research into ongoing teaching programmes.

To achieve such a significant cultural change will be a major challenge for all universities. It will require serious investment in staff development, particularly leadership development, and, crucially, following a process of negotiation, the modification of university promotion criteria to give equal weight to the four dimensions of scholarship identified earlier: discovery; integration; application; and teaching.

Third, civic leaders inside and outside the campus should work to co-create much more inclusive approaches to place-based leadership. An absence of truly effective place-based leadership, cutting across the public, business, civic, university and trade-union sectors, means that, much of the time, opportunities that would benefit a wide range of stakeholders are being missed.

In my recent book I suggested that, in many cities, ‘… universities are the sleeping giants of place-based leadership and social innovation’ (Hambleton, 2015: 306). Can we help the giant wake up?

1 The Coalition of Urban Serving Universities (CUSU) provides a good entry point for those wishing to learn more about the way in which US urban universities are harnessing the collective power of public urban research universities to influence urban policy and practice. More: www.usucoalition.org

2 The website for the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement: www.publicengagement.ac.uk

3 The Leading Places initiative was launched with six pilot projects in 2016, and a second phase, launched in 2017, involves 15 localities. For more on the Leading Places initiative visit: www.hefce.ac.uk/localgrowth/practice

4 Chaired by Lord Kerslake, former Head of the Civil Service, the Civic University Commission is now gathering oral and written evidence, and plans to publish its findings in October 2018. More information: http://upp-foundation.org

Robin Hambleton, Emeritus Professor of City Leadership, Centre for Sustainable Planning and Environments, University of the West of England, Bristol, Frenchay Campus, Bristol BS16 1QY. Email: robin.hambleton@uwe.ac.uk

Birch, E., Perry, D. C. and Taylor, H. L. (2013) Universities as anchor institutions. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 17, 3, 7-15.

Bothwell, E. (2017) Universities “generate £95 billion for UK economy”. Times Higher Education, 16 October.

Boyer, E. (1990) Scholarship reconsidered. The priorities of the professoriate. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Braginskaia, E. and Facer, K. (2017) Universities, cities and communities: co-creating urban living. Connected Communities Programme. Bristol: University of Bristol/Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Brink, C. (2018) The soul of a university. Why excellence is not enough. Bristol: Policy Press.

Centre for Cities (2018) Centre for Cities Outlook 2018. January. London: Centre for Cities.

Facer, K. and Enright, B. (2016) Creating living knowledge. Connected Communities Programme. Bristol: University of Bristol/Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Goddard, J. and Vallance, P. (2013) The University and the City. Abingdon: Routledge.

Hambleton, R. (2007) The triangle of engaged scholarship. Planning Theory and Practice, 8, 4, 549-53.

Hambleton, R. (2015) Leading the Inclusive City. Place-based innovation for a bounded planet. Bristol: Policy Press.

Hambleton, R. (2016) Pulling their weight. Times Higher Education, 3 November, p 26.

Hoyt, L. (2013) Transforming cities and minds through the scholarship of engagement: Economy, equity and environment. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

McLennan, G. (2008) Disinterested, disengaged, useless: Conservative or progessive idea of the university? Globalisation, Societies and Education, 6, 2, 195-200. CrossRef link

Piketty, T. (2014) Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. CrossRef link

Ranney, D. (2003) Global decisions, local collisions: Urban life in the new world order. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Rhodes, F. H. T. (2001) The creation of the future. The role of the American university. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2012) The price of inequality. London: Penguin.

Winkler, T. (2013) At the coalface: Community-university engagements and planning education. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 33, 2. 215-227. CrossRef link