Summary

Social enterprise, characterised by organisations enacting a hybrid mix of non-profit and for-profit characteristics, is increasingly regarded as an important component in the regeneration of areas affected by social and economic deprivation. In parallel there has been growing academic, practitioner and policy interest in ‘social value’ and ‘social impact’ within the broader ‘social economy’. This paper engages with these debates through analysis of resident perceptions of the social value created by National Lottery funded new-start social enterprise projects in ten rural UK communities. In particular it considers what can be learnt about the relationship between different approaches to social enterprise activity in rural contexts and the social value created for local people and communities.

Introduction

Social enterprise, characterised by organisations enacting a hybrid mix of non-profit and for-profit characteristics (Dart, 2004), is increasingly regarded as an important component in the regeneration of areas affected by social and economic deprivation. At the same time there has been growing academic, practitioner and policy interest in ‘social value’ and ‘social impact’ within the broader ‘social economy’ (see, for example, Barman, 2007; Ellis and Gregory, 2008; Pritchard et al, 2012; Arvidson et al, 2013). Although considerable attention has been given to measuring the value and impact of social enterprise on the individuals and communities they intend to benefit, the evidence base regarding their impacts in specific geographic contexts is less well developed (Munoz, 2010). An exception is rural settings, where there is a growing literature, some of which questions the ability of social enterprise to contribute to long term social and economic change (see Steinerowski and Steinerowska-Streb, 2012; Gore et al, 2006). This paper engages with the rural social enterprise debate as well as broader debates surrounding social value and social impact through analysis of survey data on resident perceptions of new-start social enterprise projects that aimed to create jobs and improve quality of life in ten rural UK communities. In focussing on resident perceptions this paper represents a departure from existing literature, which has tended to focus on the perspectives of the social enterprises themselves, and the wider social and economic goals of the programmes that have supported them.

The paper begins by providing a brief introduction to the concept of social value and some of the key developments surrounding it. Next, it discusses the growing evidence base on the role and effectiveness of social enterprise in addressing social and economic disadvantage in rural areas. Then, in the main empirical section, it presents the findings from a survey of more than 1,300 residents from ten rural UK communities that each received National Lottery funding to pump prime a ‘marquee’ social enterprise project: it provides some brief descriptive analysis before focussing on the findings from an analysis of a logistic regression (logit) model. The paper concludes by discussing the implications for social enterprise in rural contexts and considers what can be learnt about the relationship between different approaches to social enterprise activity and the social value created for local people and communities. In particular it argues that in order to maximise the contribution to social value for residents in rural areas social enterprise needs to strike a balance between competing social, economic and environment objectives.

An introduction to social value

‘Social value’ is a somewhat ‘fuzzy’ concept which for a long time lacked a clear or authoritative definition. It has historically been associated with approaches measuring outcomes and social impact within social economy organisations but more recently it has become associated with public services and commissioning. In March 2012 the Public Services (Social Value) Act received Royal Assent. The Act requires that public authorities: i) have due regard to the economic, social and environmental well-being impacts of procuring public services, and; ii) must consider whether to consult on this issue at the pre-procurement stage. The Act applies to public services contracts and framework agreements across almost the entire public sector and aims to facilitate the growth of social enterprises, charities, cooperatives and commercial enterprises with a social agenda, and to have a positive impact in the areas where public services are commissioned. As a result, measures of social value have come to play an important role in debates about how social enterprises and charities conceptualise, measure and communicate their achievements (Arvidson et al, 2013); and about how public sector bodies identify, measure and compare social value when commissioning services. Although these debates remain contested, and a commonly accepted definition of and approach to measuring social value does not exist, this paper uses a working definition of social value which refers to the identifiable economic, social and environmental well-being benefits associated with an organisation’s activities.

The role of social enterprise in the social and economic regeneration of rural areas

It is argued that that the most effective way to support the social and economic regeneration of rural areas is through “bottom-up” approaches to development which empower communities to identify local needs and determine the schemes and projects through which they are addressed (Ward and McNicholas, 1998). This view contends that traditional “top-down” approaches to development cannot adjust to specific rural contexts and circumstances (Ashley and Maxwell, 2001; Johnson, 2001; Terluin, 2003). In response, integrated rural development (IRD) policies that link economic, social and environmental objectives emerged as the favoured approach for regenerating rural areas, alongside a shift from government towards governance through which attempts to coordinate government funding, provision and direction at municipal level have been supplanted by governing styles in which boundaries between and within public, private and voluntary sectors are more blurred (Shucksmith, 2010; Stoker, 1996). This has involved a move away from state controlled economic and social programmes towards delivery through partnerships involving networks of public, private, and voluntary sector bodies (Shucksmith, 2010; Goodwin, 2003).

To summarise, the increasingly ‘bottom-up’ nature of rural social and economic development policy reflects the principles that rural communities are better placed to respond to local needs, that local participation should be a fundamental feature in the development and implementation of those responses, and that they should enable the capacity building of indigenous human resources (Gore et al, 2006; Shortall and Shucksmith, 2001). This ought to enable an environment that is supportive for the development of locally owned enterprises in rural areas (often referred to as Rural Community Businesses – RCBs), and of social enterprise in particular. This is particularly important as a large proportion of social enterprise is located in rural areas (Harding, 2006) and the role social enterprise can play in rural service provision and in supporting community life, and the diverse array of roles it can fulfil, is a strong theme emerging from the study reported in this paper. However, it is important to recognise that recent rural development initiatives have faced a number of implementation challenges, and that the ability of social enterprise approaches to contribute to long term rural social and economic change on their own is far from evident.

A particular challenge facing rural development policies is the delicate balance between social, economic and environmental objectives, and the difficulty of integrating disparate and often divergent domains (Gore et al, 2006). This tension is reflected in the literature. For example, Pepper (1999) argues that economic considerations such as job and business creation are too predominant within some programmes, while Shortall and Shucksmith (2001) were critical of programmes for placing too much emphasis on community development ahead of economic regeneration. It is argued that economic considerations may be more likely to dominate in deprived rural areas (Gore et al, 2006), where programmes often focus on the notion that retaining people in rural areas is key, and that this can be achieved through economic development and job creation (Pepper, 1999). In short, this suggests that at a programme level rural development initiatives tend to focus on either economic goals or social and community issues, with approaches that incorporate the two being far rarer (Bryden et al, 1997). As a result, it has been argued that although many rural programmes have contained ‘bottom-up’ features, the extent to which they have been fully integrated is questionable (Thompson and Psaltopoulos, 2004).

Furthermore, Gore et al (2006) cast considerable doubt over the ability of Rural Community Businesses (including social enterprises) to make a full contribution to rural social and economic development. For while their aims and objectives are highly consistent with current approaches to governance, their main contribution lies in the way they mobilise local volunteer action and strengthen the social fabric of an area, whilst their contribution to economic goals (jobs and growth) is far less evident. There is further evidence regarding social enterprise to support this conclusion. For example, Steinerowski and Steinerowska-Streb (2012) identified a range of promoters and barriers to the success of social enterprises in rural contexts. Promoters included market context (lack of competition), a culture of self-help (sense of community) and scale (small and flexible). Barriers included geography (isolation), access to workforce (lack of skills), market size (small) and insufficient availability support (networks and opportunities to collaborate). This led Steinerowski and Steinerowska-Streb (ibid) to conclude that, although social enterprises might contribute to creating sustainable communities, to do so they need to do so they must be sustainable themselves. In this context the ability of social enterprise, as a scalable local response to social and economic regeneration in rural areas, to contribute to the multiple and often conflicting aims of rural development remains a subject of contested debate.

The study

This section of the paper draws on evidence from a Programme Evaluation of National Lottery funding that enabled the ten rural social enterprise projects to be developed. Broadly, the evaluation explored how the social enterprise models pursued by the funded projects helped revive rural communities and enrich residents’ lives. It featured a postal survey of more than 1,300 residents across the ten communities undertaken approximately 12 months after the projects had started. Evidence from this survey provides the empirical basis of the paper but information on the background to the funding programme and the social enterprise projects it supported draws on qualitative stakeholder interviews and documentary analysis carried out as part of the wider evaluation.

This paper is therefore markedly different from those discussed in the previous section in that it focusses extensively on the views of local residents (whether or not they were directly involved), rather than the organisations themselves, or the wider social and economic goals of the programme. As such it provides a unique ‘bottom-up’ perspective of the impact of the social enterprises in question and their ability to create place based social value for local people and communities.

Background to the funding programme

The funding programme was launched in June 2009 and challenged village communities across the UK to develop ideas for community led enterprises which would help to revive rural localities by creating jobs and improving quality of life for local people. It sought to highlight and provide templates for addressing the social and economic decline afflicting many of the UK’s rural areas; some of which are increasingly characterised by rising unemployment, low wages, a prevalence of small businesses and self-employment and declining local infrastructure. However, the problems faced by rural communities vary in nature and severity and therefore may require bespoke responses. In recognition of the diversity and the vulnerability of the UK’s rural communities, the programme sought to encourage rural communities to develop innovative and appropriate solutions to the problems they faced. In this sense the programme, with its emphasis on community-led bottom-up responses to rural problems, embodied many of the central principles of bottom-up rural governance discussed earlier in this paper.

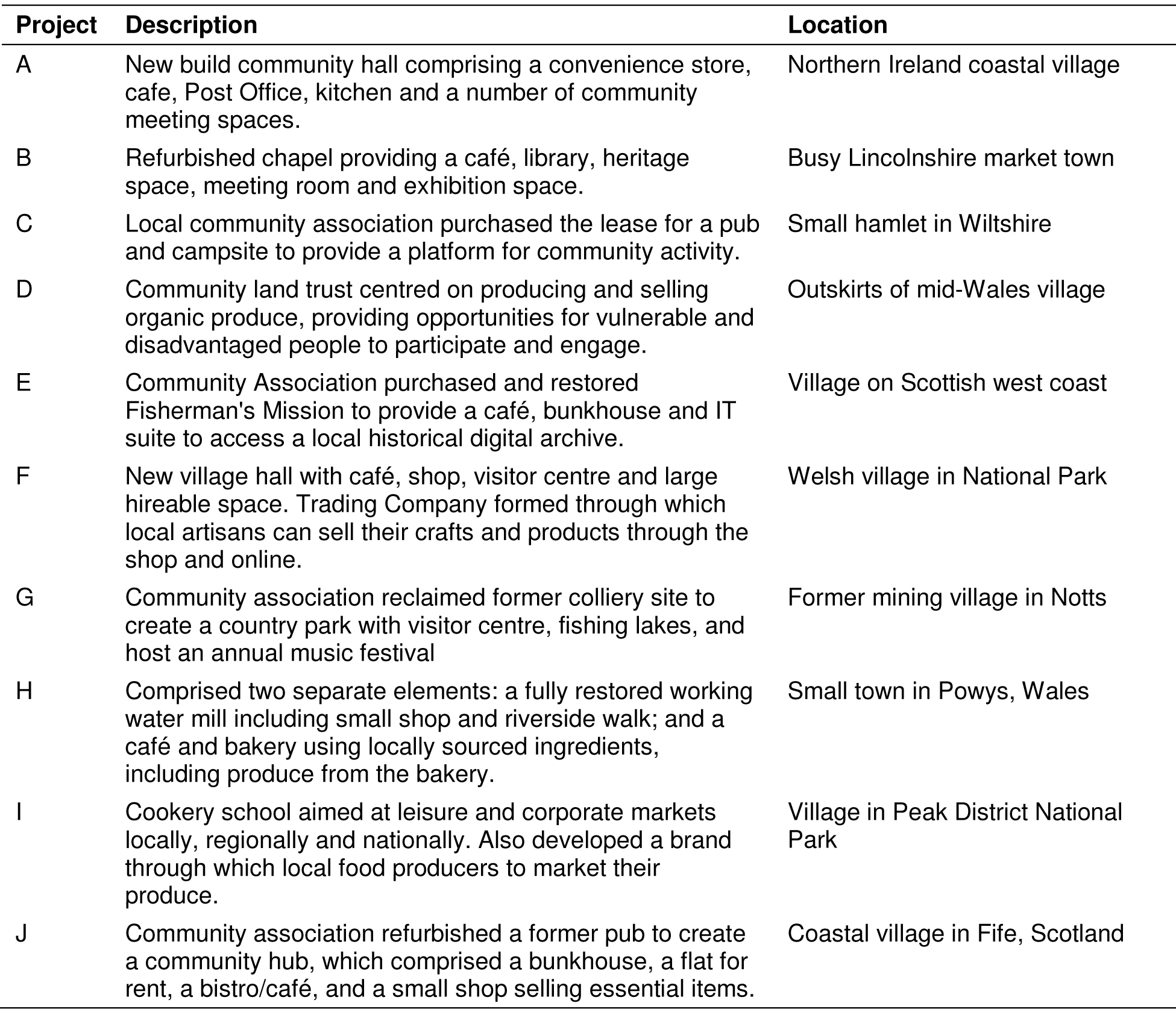

The ten social enterprise projects

Table 1 provides a brief summary of the 10 funded projects. The following table 2 provides a typological overview of their social enterprise activity. Each scheme received a grant of around £400,000 to support a mix of capital and revenue activities. The grants were intended to pump prime a social enterprise business model with the intention that it should be self-sustaining or surplus generating in the medium to longer term.

Survey methodology

A postal questionnaire was sent to a sample of 4,592 households located in or near the villages or towns where the ten projects were located. Each area was bounded according to the area of benefit identified in the project business plans and the sample was stratified to ensure all ten areas were covered as equally as possible: in areas where fewer than 500 households could be identified a questionnaire was sent to every address; in areas with more than 500 households a questionnaire was sent to a random sample of 500 addresses. 1,328 valid responses to the survey were received providing a relatively large and robust sample through which to undertake a programme level analysis of impact: the estimated maximum 95 per cent confidence interval for the response sample was +/-2.5 percentage points. Uneven response rates to the questionnaire across the ten areas made it necessary to weight the data to ensure each area was represented equally. Note that as a result of this weighting the final sample had an implied effective base of 1,211 cases.

In the questionnaire residents were asked about their awareness of, engagement with, and participation in the project in their area, and to provide their views on the extent to which it would contribute to a range of social and economic outcomes. Whether respondents thought the local area would be a better place to live as a result of the funded social enterprise project was used as the dependent variable to provide a common headline measure of the social value of the projects for local people. The findings therefore provide one indication of the personal utility created by the projects for an important stakeholder group.

Descriptive analysis

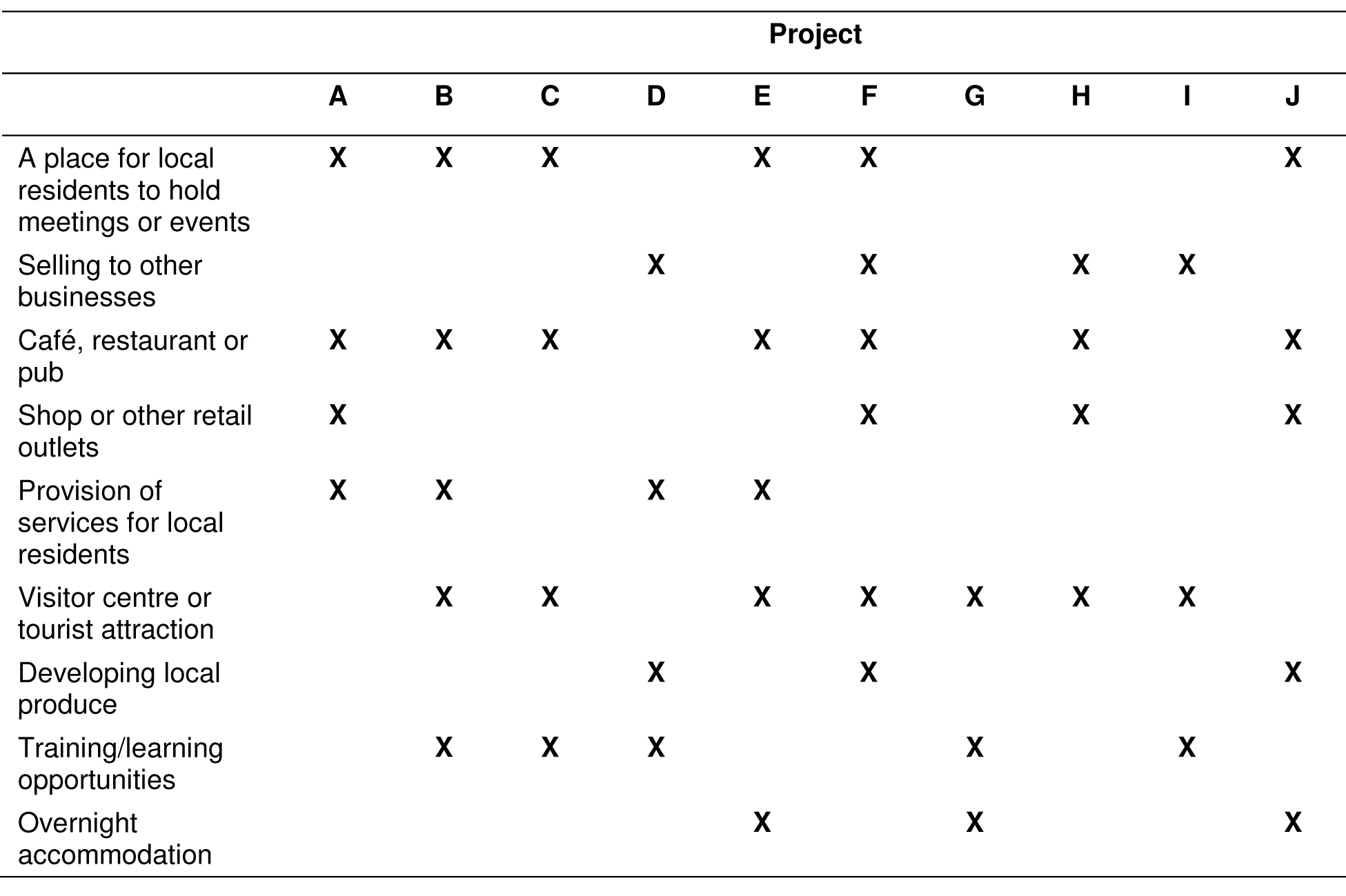

Figure 1 provides an overview of the dependent variable by project. It shows that overall, a majority of respondents (57 per cent) thought the local area would be a better place to live as a result of the social enterprise project in their area. When only the responses from residents within the immediate vicinity of the projects are considered (narrow geography), more residents, 61 per cent, thought the area would be a better place to live as a result of the project compared to only 54 per cent of respondents from beyond the village boundaries (wider geographies). This suggests that proximity to a project does influence residents’ views regarding its social value.

The survey also revealed wide variations by project, ranging from 96 per cent of respondents identifying positive social value in project A to only 32 per cent in project I. These variations are likely to reflect, at least in part, the type of project that was developed in a particular area. The wide variety of projects inevitably means that some projects will have greater ‘reach’ into the community (for example, a community hall and shop) than others (for example, a tourist/visitor attraction). This issue is explored in more detail through the analysis presented in the following sections.

Regression analysis

A logistic regression (logit) model was developed to explore in more detail the factors associated with the dependent measure of social value measure discussed in the preceding section. The following variables were included in the model as independent explanatory variables:

- Demographic characteristics: gender; age group; length of residency; economic status

- Involvement: frequency of involvement

- Outcomes attributed to the projects: getting on better with other residents; having better access to services; being more likely to participate in local groups; being less likely to move away from the area; more employment in the local area; more tourists and visitors to the area.

Demographic characteristics were included to control for individual features of respondents and involvement was included in the model as it was identified throughout the descriptive analyses as an important factor associated with outcomes. The outcome variables were chosen to represent the different outcomes and benefits the projects were perceived to have.1

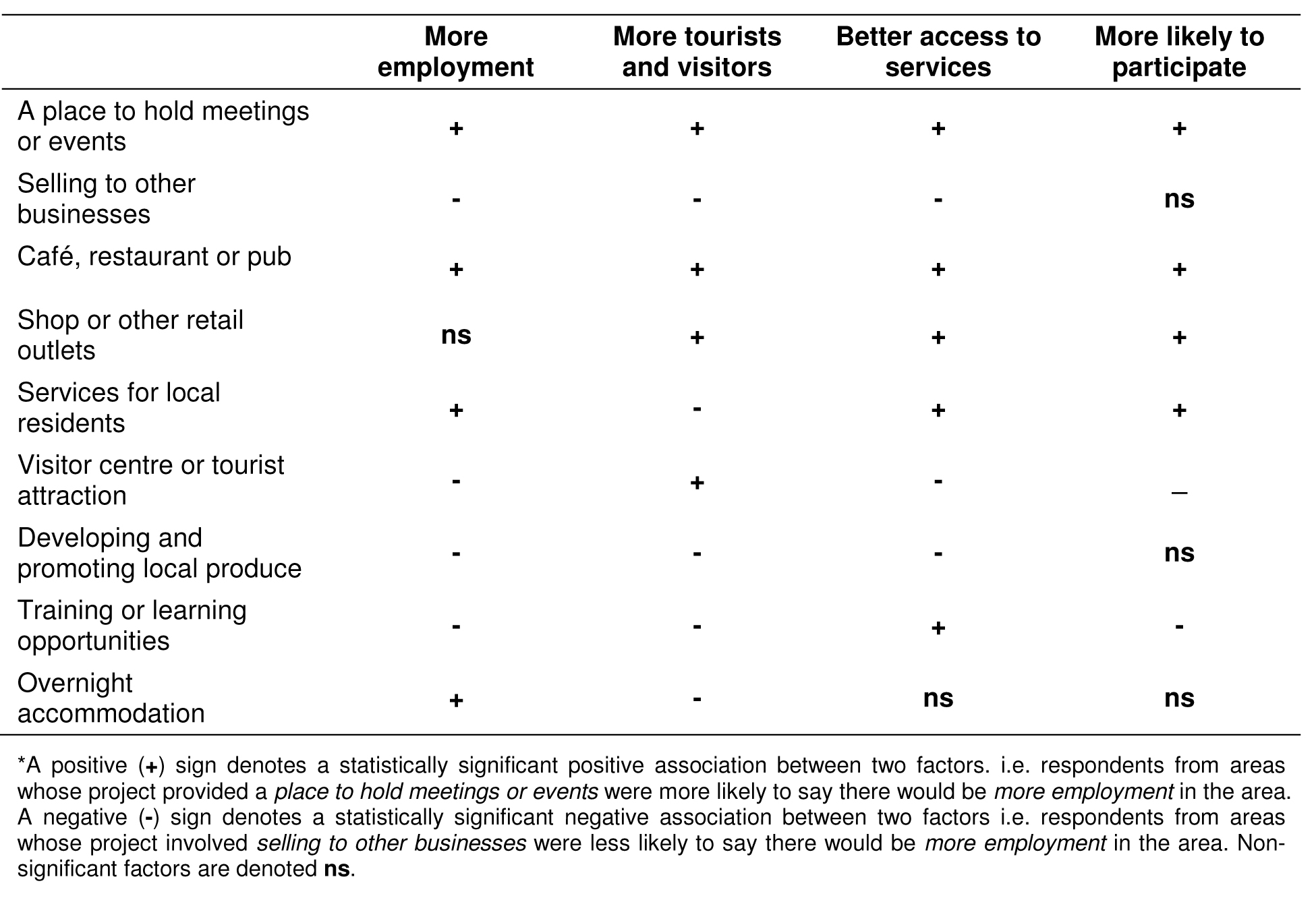

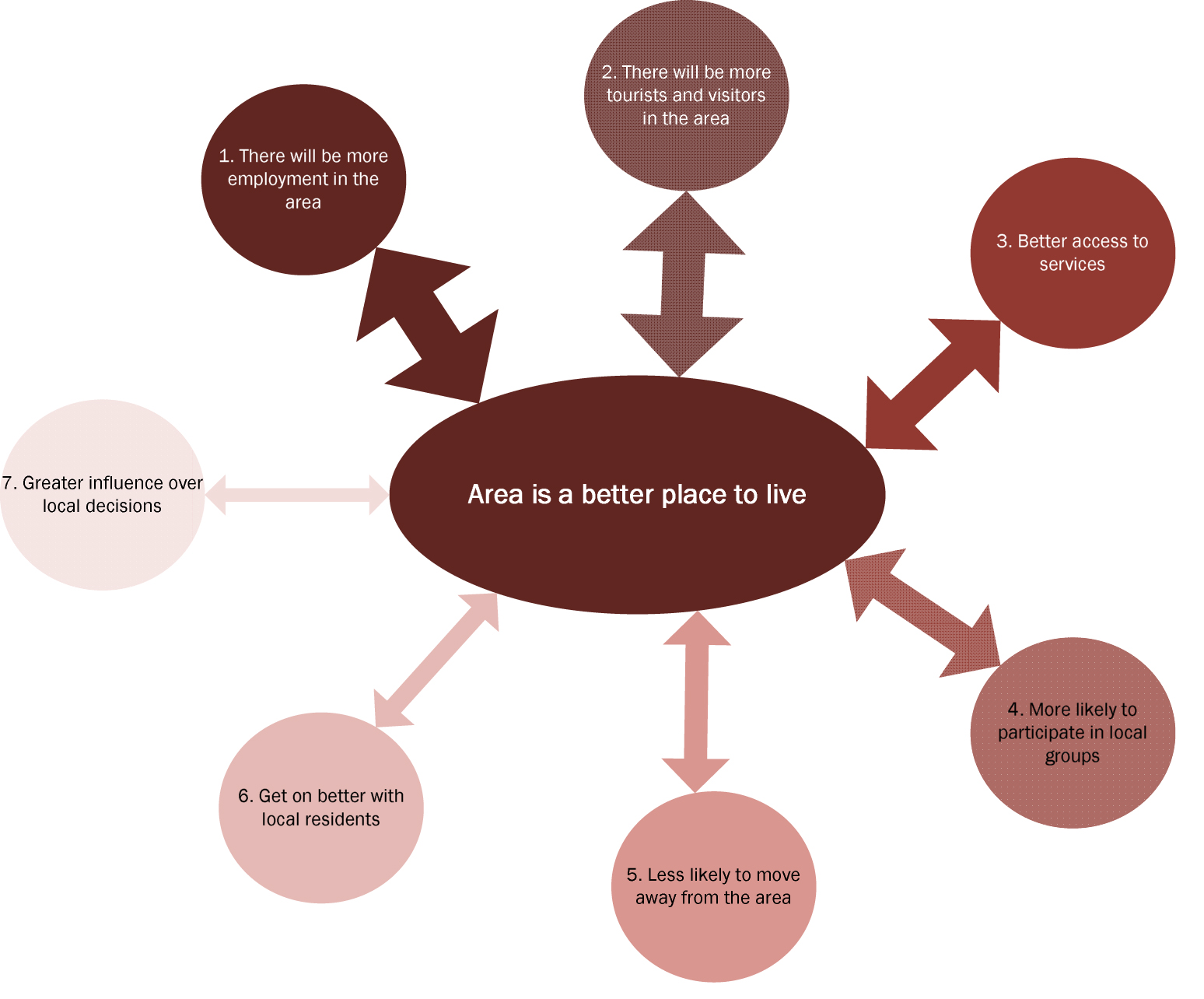

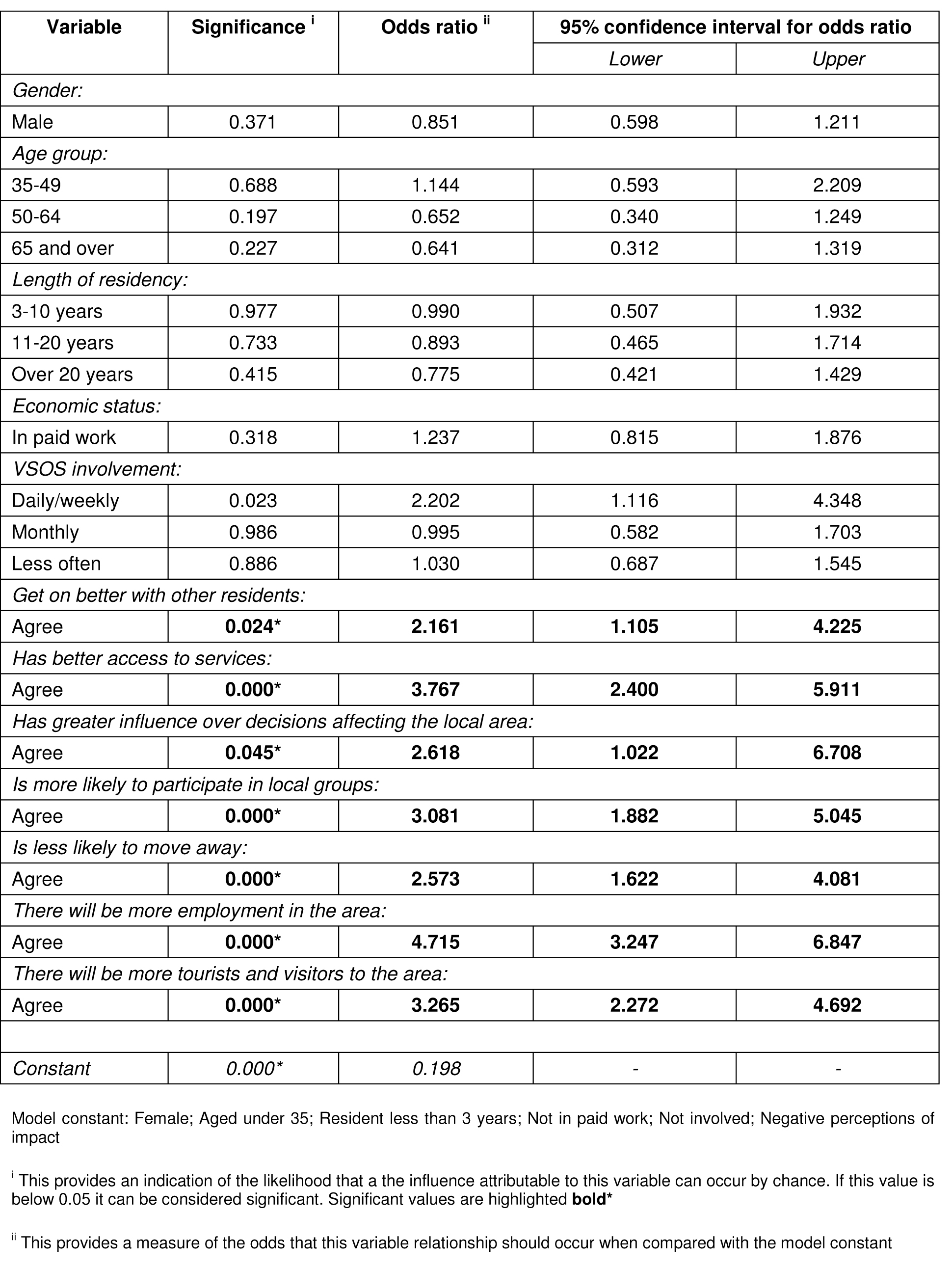

Figure 2 provides a visual summary of the model findings by depicting the seven statistically significant factors and the relative strength of their association with the dependent variable. The following Table 3 provides a more detailed overview of the model.

The model indicated that economic benefits were more strongly associated with resident perceptions of programme impact than social benefits. It also showed that demographic factors such as gender and age were not significant. Whether or not residents thought the project in their area would lead to more employment was the most important factor associated with overall impact followed by whether or not it would bring more tourists or visitors to the area. Both measures are indicators of the perception amongst residents that their local project would bring economic benefits to the area.

Of the perceived social benefits associated with the projects, providing better access to services was the most important factor, followed by being more likely to participate in local groups and being less likely to move away from the area. Although getting on better with local residents and having greater influence over local decisions were significant factors they were far less important than the other types of perceived benefit.

Figure 2: Factors with a statistically significant association with programme impact and their relative importance*

*The darkest shading and widest arrows indicate the strongest association (1); the lightest shading and narrowest arrows indicate the weakest association (7).

Table 3: Logistic regression model summary

The logistic regression model provides a relatively powerful overarching analysis of the factors associated with positive social value creation. The model demonstrates that residents’ views about the outcomes the project has had for them and will have for the local area were important predictors of their views regarding its overall social value: residents who identified positive outcomes were most likely to believe the project would make the area a better place to live. By contrast there was no statistical evidence that residents’ demographic characteristics predicted their views on this value.

Of the outcomes included in the model, residents identifying positive economic outcomes (more employment, more tourists and visitors) for the area were the most powerful predictors of positive social value, followed by the perception that the project would create better access to services, and mean they were more likely to participate in local groups. These outcomes can be understood in more detail through further descriptive analyses, which provided an indication of the types of social enterprise activity that were positively and negatively associated with each outcome.

Further descriptive analysis

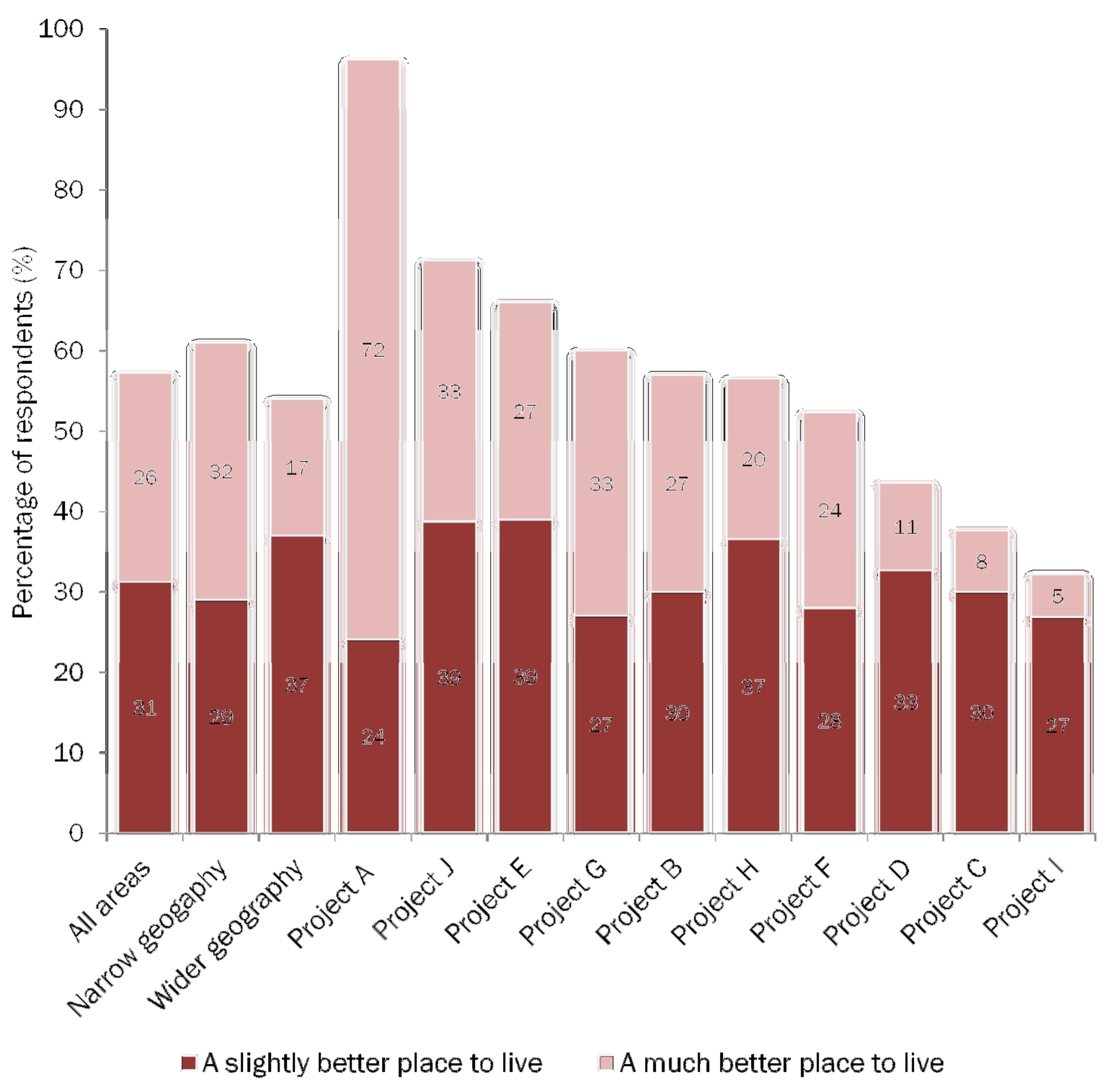

The relationships between different outcomes and the project activities outlined in the earlier typology (table 2) are summarised in table 4.

Table 4 indicates that two types of project activity, providing a place for local residents to hold meetings or events and providing a café, restaurant or pub were positively associated with all four outcomes, while providing a shop or other retail outlets was positively associated with three of the four outcomes (all bar more employment). It also shows that several factors; selling to other businesses, developing and promoting local produce, visitor centre or tourist attraction, and training or learning opportunities; were negatively associated with three of the four outcomes.

In some senses this latter finding seems somewhat counterintuitive to the model findings: the model identified economic outcomes as the most important predictors of impact yet the project activities with the most obvious economic focus such as selling to other businesses, developing and promoting local produce were often negatively associated with outcomes. However, these activities are unlikely to ‘reach’ large numbers of local people and the perceived social benefits (access to services, opportunities to participate) that the model also identified as important are less clear to residents. As a result their impact (or their impact in the eyes of local residents at least) appears to have been less positive, probably because they do not have the potential to reach a broad local audience in the way that community meeting spaces, shops and cafes do.

A comparison that illustrates this point is between project A (where resident perceptions of impact were highest) and project I (where it was lowest). In area A the local project provided the village’s only shop, post office and café, and a much needed community hall and meetings rooms. By contrast in area I the local project created a ‘School of Food’ that primarily targeted people from outside the village and undertook a range of events and activities to support and promote local food retailers and producers. To people in area I the need for the project was less evident and the direct benefits for their lives and the prospects of the area less discernible.

Although the project activities described were clearly an important factor, involvement with the project consistently emerged from descriptive analyses as the factor with the strongest association with positive resident perceptions regarding outcomes. Residents who had some form of involvement with the project were more likely to identify positive social value than those who had not, with those whose involvement was most frequent most likely to be positive.

Resident involvement was highest in projects that provided a place for local residents to hold meetings or events, a café, restaurant or pub and shop or other retail outlets and lowest in projects that involved selling to other businesses, developing and promoting local produce, and provided training or learning opportunities. In many ways this reflects the findings about project activities, as it was the types of activity that brought projects into frequent contact with local residents and had the potential to reach furthest into local communities that were most strongly associated with positive views regarding the social value of projects, now and in the future.

Discussion: understanding the place based social value created by rural social enterprise

The survey findings demonstrate that if the economic activity of a social enterprise does not have a significant impact on economic opportunity in the area then it is less likely be perceived positively by local people; but they also indicate that too much focus on economic objectives may lead to an enterprise that is disconnected from local people and does not foster sufficient voluntary association to enable a broader series of social or environmental outcomes to be achieved. This is illustrated by the contrast between the projects in areas A and I discussed earlier in this paper. Although both led to identifiable benefits Project A was able to create a greater impression of value and impact for local residents than Project I because its activities benefited and involved a large proportion of the local population and filled several gaps in local service provision.

This supports arguments made in earlier literature that in order to maximise the contribution to social value for residents in rural areas social enterprise needs to strike a balance between competing social, economic and environment objectives (for example Gore et al, 2006; Pepper, 1999; Shortall and Shucksmith, 2001). In particular they support literature emphasising the importance of ‘bottom-up’ components in rural development activity (for example, Ward and McNicholas, 1998): the argument that rural communities are better placed to identify and respond to local needs, and that local participation should be a fundamental feature of those responses.

It is important to recognise that this paper focusses on one very broad top-down measure or definition of social value – the ability of a rural social enterprise to improve an area as a place to live – for one stakeholder group (local residents). In this context it is important to recognise that a wide range of other project and area level outcomes and impacts not covered by this study are likely to have occurred. Indeed, multiple stakeholder configurations are a key feature of hybrid social enterprises (Anheier, 2010) and a stakeholder focussed approach to evaluation (such as Social Return on Investment2), particularly at a project level, would likely have uncovered a broader and more varied series of social value benefits for a range of different stakeholders. For example, Project D may lead to specific well-being benefits for vulnerable and isolated people; projects with a café, restaurant or public are likely to lead to identifiable economic benefits in the form of net additional job creation; and Project G, with its reclaimed former colliery site may well lead to long term environmental benefits in the form of green space brought into public use, and new or protected habitats.

It should also be noted that the study captured resident perceptions of social value during the early stages of the projects (approximately 12 months into delivery). It may be that the benefits of certain types of activity, in particular those exhibiting greater for-profit characteristics, will take longer to materialise or achieve the scale necessary to benefit significant numbers of local people. The rate at which these benefits accrue will also be affected by local context, in particular the effects of the economic downturn and the associated withdrawal of state (through for example public sector spending cuts and welfare reform) and the market from some local areas.

Conclusion

This paper has presented findings from a survey of residents from ten rural UK communities in receipt funding to establish a major local social enterprise project. The survey provided evidence regarding residents’ awareness of, engagement with, and participation in the project in their area, and explored their views on the extent to which it would contribute to place based social value by making the area a better place to live. The survey findings have been used to illustrate lessons regarding the relationship between different approaches to rural social enterprise activity, and the social value created for local people and communities. The data provides useful evidence on the types of social enterprise that are likely to create place based social value for residents in rural communities in the short term. In particular it highlights the challenge of balancing for-profit activities without compromising the principles of voluntary association and responsiveness to local needs that underpin social economy activity in order to maximise social value creation.

However, for the social enterprise projects covered by this study and for rural social enterprise more generally, a number of barriers may prevent this social value potential from being realised. In particular they will need to achieve sufficient scale, longevity and sustainability that the value created for local people to date can be sustained and expanded into the future. This represents a significant challenge in the current economic and political context, but one which will need to be overcome if social enterprise is to have a significant and lasting impact on individual and community life.

1 It should be noted that several outcome measures from the survey were removed from the model in steps, as they were found to interact with one or more other variables in the model. For example ‘More business in the area’ interacted with ‘More employment’ and ‘More visitors’ in a way that distorted the findings, so was excluded from the final model.

2 SROI is an approach towards identifying and appreciating value created by organisations and the projects, activities and services they provide. It involves a diverse range of stakeholders in reviewing the inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts made and experienced by stakeholders in relation to particular projects, activities and services, and putting a monetary value on the social, economic and environmental benefits and costs created. The SROI guide, published by the Cabinet Office, outlines a methodology for calculating value as well as prescribing a set of principles for the framework.

This paper draws on data collected as part of a broader programme evaluation undertaken by a team from the Centre of Regional Economic and Social Research (CRESR) at Sheffield Hallam University on behalf of the Big Lottery Fund. I would like to thank everyone from the Evaluation Team whose contributions have enabled the writing of the paper but particular thanks are due to Ian Wilson, Professor Peter Wells and Professor Paul Hickman for their advice, support and guidance during the development of the survey and during the analysis process. Thanks are also due to Hillary Leavy and her colleagues at the Big Lottery Fund for their helpful input and feedback throughout the Evaluation. A full evaluation report can be accessed through the following link: http://www.biglotteryfund.org.uk/er_vsos_final.pdf.

An earlier iteration of this paper – Understanding resident perceptions of the impact of rural social enterprise: the relationship between hybridity and social and economic benefit – was presented at the 4th International Social Innovation Research Conference (ISIRC), 12-14 September 2012, Third Sector Research Centre, University of Birmingham.

Chris Dayson, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University, Unit 10 Science Park, City Campus, Howard Street, Sheffield, S1 1WB. Email: c.dayson@shu.ac.uk

Anheier, H. (2011) Governance and Leadership in Hybrid Organisations. Comparative and Interdisciplinary Perspectives, pp. 1-7 Background paper. Heidelberg: Centre for Social Investment, University of Heidelberg.

Arvidson, M., Lyon, F., McKay, S. and Moro, D. (2013) Valuing the social? The nature and controversies of measuring social return on investment (SROI). Voluntary Sector Review, 4, 1, 3-18.

Ashley, C. and Maxwell, S. (2001) Rethinking rural development. Development Policy Review, 19, 4, 395-425. CrossRef link

Barman, E. (2007) What is the Bottom Line for Nonprofit Organizations? A History of Measurement in the British Voluntary Sector. Voluntas, 18, 101–115. CrossRef link

Billis, D. (Ed.) (2010) Hybrid Organizations and the Third Sector. Challenges for Practice, Theory and Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bryden, J., Watson, R., Storey, C. and van Alphen, J. (1997) Community Involvement in Rural Policy. Edinburgh: Scottish Office Central Research Unit.

Dart, R. (2004) The Legitimacy of Social Enterprise. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 14, 4, 411-423. CrossRef link

Ellis, J. and Gregory, T. (2008) Accountability and learning: developing monitoring and evaluation in the third sector – Research report. London: Charities Evaluation Services.

Goodwin, M. (2003) Partnership working and rural governance: issues of community involvement and participation. Paper presented to Social Exclusion and Rural Governance Seminar, DEFRA, ESRC and Countryside Agency, 28 February 2003.

Gore, T., Powell, R. and Wells, P. (2006) The contribution of rural community business to integrated rural development: “Local services for local people”. Cahiers d’economie et sociologie rurales, 80, 30-52.

Harding, R. (2006) Social Entrepreneurship Monitor United Kingdom 2006. London: London Business School.

Johnson, T. (2001) The regional economy in a new century. International Regional Science Review, 24, 1, 21-37. CrossRef link

Mullins, D., Czischke, D. and Van Bortel, G. (2012) Exploring the Meaning of Hybridity and Social Enterprise in Housing Organisations. Housing Studies, 27, 4, 406-417. CrossRef link

Munoz, S. A. (2011) Towards a geographical research agenda for social enterprise. Area, 42, 3, 302-312.

Pepper, D. (1999) The integration of environmental sustainability concerns into EU development policy: A case study of the LEADER initiative in Northern Ireland. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 42, 2, 167-187. CrossRef link

Pritchard, D., Ní Ógáin, E. and Lumley, T. (2012) Making an Impact: Impact measurement among charities and social enterprises in the UK. London: New Philanthropy Capital.

Public Services (Social Value Act) (2012) (c. 3) London: HMSO.

Shortall, S. and Shucksmith, M. (2001) Rural development in practice: Issues arising in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Community Development Journal, 36, 2, 122-133. CrossRef link

Shucksmith, M. (2009) Disintegrated Rural Development? Neo-endogenous Rural Development, Planning and Place-Shaping in Diffused Power Contexts. Socioliga Ruralis, 50, 1, 1-14. CrossRef link

Steinerowski, A. and Steinerowska-Streb, I. (2012) Can social enterprise contribute to creating sustainable rural communities? Using the lens of structuration theory to analyse the emergence of rural social enterprise. Local Economy, 27, 2, 167-182. CrossRef link

Stoker, G. (1996) Public-private partnerships and urban governance. In: J. Pierre (Ed.) Partners in urban governance: European and American experience. London: Macmillan: 34-52.

Terluin, I. (2003) ‘Differences in economic development in rural regions of advanced countries: an overview and critical analysis of theories’. Journal of Rural Studies, 19, pp. 327-344. CrossRef link

Thompson, K. J. and Psaltopoulos, D. (2004) “Integrated” rural development policy in the EU: A term too far? EuroChoices, 3, 2, 40-45. CrossRef link

Ward, N. and McNicholas, K. (1998) Reconfiguring rural development in the UK: Objective 5b and the new rural governance. Journal of Rural Studies, 14, 1, 27-39. CrossRef link