Summary

Despite trust’s perceived importance in participatory local governance, very few studies, theoretical and empirical, have devoted attention specifically to understanding their interaction. Focussing on resident participation in urban regeneration, this paper identifies shortcomings in the literature’s theoretical grasp of trust. This has led to a trust-participation paradox: some academics have suggested that increasing resident trust in officers, institutions or their community will result in more participation, whilst others have argued that lower trust leads to greater participation. This paper suggests that the key to solving this theoretical quandary is to relinquish the perception of trust as a monolithic concept and recall its context-dependent nature. It proposes several forms of trust which could theoretically impact on residents’ willingness to participate in urban regeneration: receptivity trust; ability trust; and representative trust. It concludes with recommendations for future theoretical and empirical research.

Introduction

Trust is a much sought social phenomenon. It is difficult to overstate its perceived importance both today and throughout the history of social and political thought. Weil (1986) argues that trust is central to 17th Century philosopher Thomas Hobbes’ belief in the necessity of a sovereign Leviathan. Hardin (1993: 519) suggests that a complete lack of trust would ‘utterly subvert individual existence’; Dasgupta (2000: 49) believes that ‘trust is central to all transactions’; Giddens (1990) argues that a basic form of trust is necessary in order for us to maintain our ‘ontological security’; and Rotter (1971) asserts that the weakening of trust would result in social collapse.

Such thoughts have been carried through into social research exploring public participation. Whilst the academic literature commonly models the development of trust, either between participants and institutions or within communities, as an aim or product of public participation, this article models trust as a means. Indeed, the positive role that trust may play in building consensus and co-operation across a wide variety of fields is well documented (Edelenbos and Klijn, 2007; Krameret al., 1999; Kumar and Paddison, 2000; Sztompka, 1999; Vangen and Huxham, 2003; Walker et al., 2010). Some have considered the role of social or ‘generalised’ trust in motivating participation in civil society (Brehm and Rahn 1997; La Porta 1997). There have been suggestions of a positive feedback loop which holds that ‘honesty, civic engagement, and social trust are mutually reinforcing’, leading to claims of a ‘virtuous circle’. (Putnam, 2000: 137; 138-139).

This paper considers trust and its influence on residents’ willingness to participate in local decision making, specifically in relation to urban regeneration programmes. Many have acknowledged the need either to build trust or to overcome its absence in order to encourage public participation in this domain (Fordham et al., 2009; Hibbitt et al., 2001; Jarvis et al., 2011; Lister et al., 2007; Purdue, 2001; Russell, 2008). This also has been reflected in some British policy documents (ODPM, 2004, 2006; DCLG, 2008). However, this literature rarely defines or discusses trust conceptually. Furthermore, there is little empirical evidence to suggest that trust is a predictor of participation (Dekker, 2007; Duffy et al., 2008; Hoppner et al., 2008; Hoppner, 2009; Koontz, 2005; Raymond, 2006). This paper suggests that these findings could be the result of insufficiently developed conceptualisations, with not enough focus on the ‘objects’ of trust. What do academics mean when they suggest ‘trust’ should be built between residents and officers and/or organisations in regeneration projects? What should they be trusted to do? Developing effective measures of trust may well continue to prove difficult without fully exploring the meaning of the term in specific policy contexts. Without improved methods of measuring trust which recognise its multi-faceted nature, it will remain a challenge to determine its potential association with participation. These issues have significant ramifications for both policy-makers and practitioners working within regeneration. Should policy-makers devise methods of encouraging participation which focus on trust-building with communities? If so, what forms of trust should officers attempt to develop with the public?

Building on the work of Hoppner (2009), this article sets out to theoretically consider the concept of trust in relation to participation in urban regeneration. It begins with a discussion of trust, developing both a workable definition derived from organisational literature and a tripartite model for its application. The paper moves on to explore the oft-stated relationship between trust and participation in the field of urban regeneration in research, identifying concerns of superficiality in the literature’s application of the term. It also draws attention to an alternative theory, which argues that trust may actually deter potential participants from becoming involved in local decision-making. This suggests a paradox – there appear to be logical arguments as to how trust may both increase and decrease participation in governance. The paper argues that solving this theoretical impasse may require greater consideration as to the nature of trust, which, by default, has been inferred as uniform rather than context-dependent (Hoppner, 2009). The paper attempts to diffuse some of the confusion in the literature by considering three potential forms of trust, based upon the objects of trust in officers: receptivity trust; ability trust; and representative trust. It considers the hypothesised relationship of each with residents’ willingness to participate and concludes by arguing for empirical research to explore and test these suggestions, providing recommendations as to how this might be undertaken.

Trust

A wide variety of definitions of trust have been applied across an expansive array of academic fields (Laeequddin et al., 2010). However, Metlay (1999: 101) comments, ‘it is striking just how often ‘trust’ is either an undefined term or a term defined using concepts that circle the reader back to the notion of trust’. Kramer (1999) notes that conceptualisations of trust in the organisational field have been influenced by both psychological and ‘choice behaviour’ literature. Whilst the former claims that trust exists as a psychological state which influences behaviour (Mayer et al., 1995; Rousseau et al., 1998), the latter tends to argue that the phenomenon of trust is contained within the observable decisions made by actors (Coleman, 1990; Dietz, 2011; Sztompka, 1999). Li (2007) refers to these positions as ‘trust-as-attitude’ and ‘trust-as-choice’, describing them as a ‘duality of trust’ which is at the heart of the discussion about the concept.

This article uses the psychological account of trust for two reasons. Firstly, the literature which stimulated the writing of this article, which extolls trust’s positive impact on participation, treats the terms as distinct. If trust is behaviour then trust isparticipation – if we choose to participate we choose to trust. This would render all calls to increase participation through building trust as meaningless, since they can be reduced simply to arguments for more participation. Secondly, acts which would be viewed as trusting behaviour from a choice perspective may not involve trust at all. This may create methodological problems for researchers. For example, if one were to oblige a colleague who asks to borrow some money, the behavioural view would perceive this as an act of trust. The psychological perspective rejects this, holding that trust may or may not have influenced the individual’s behaviour. The individual may notexpect to receive the money back, but may, for example, simply seek approval from their colleague or any onlookers. They may feel it is morally right to lend the money, regardless of the consequences, or they may feel coerced into doing so given their relationship with the colleague. Conversely, certain behaviours may infer a lack of trust where it does in fact exist. The individual in the above example may choose not to lend the colleague money because s/he does not approve of their recent conduct in the workplace, even though they trust them to return the lent sum – but it would seem to someone from a choice perspective that they do not trust them. Trust is only one of many factors which can influence behaviour. This paper therefore distinguishes between trust and “acts of trust”, accounting for nuanced problems in trust research.

The definition of trust used in this article is an amalgamation of those by Rousseau et al (1998: 395) and Mayer et al (1995: 712) who have investigated the concept in relation to organisations:

A psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon expectations of another party’s intentions or behaviour, which are of consequence to the trustor, irrespective of their ability to monitor or control the trustee.

Trust may be felt toward an individual, group or organisation. The trusting individual will be referred to as the ‘trustor’ and the trusted party as the ‘trustee’, or ‘subject’ of trust.

Much of the literature on trust argues that it is, at least in part, dependent upon an individual’s ‘disposition to trust’ (Currall and Judge, 1995; Gillespie, 2003; Kramer, 1999; Mayer et al.,1995). This has also been referred to as one’s capacity or propensity to trust (Hardin, 1993; Mayer et al., 1995) or social or generalised trust (Putnam, 2000; Sturgis et al., 2012). It is often traced back to the work of Rotter (1971) who considered trust in relation to social learning theory. Within this context, ‘an expectancy is a function of a specific expectancy, and a generalized expectancy resulting from the generalization from related experience’ (ibid: 445). Our experiences with others lead us to form a view of the trustworthiness of a generalised other. If an individual has had favourable experiences with others they will have higher generalised trust than those who have had interactions where their trust has been betrayed. It is this generalised trust in society which Putnam (2000) focuses on in his exploration of social capital. He defines social capital as the ‘connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them’ (ibid: 19). He later argues that, ‘social trust is not part of the definition of social capital but it is certainly a close consequence, and therefore could be easily thought of as a proxy’ (Putnam 2001: 7). Indeed, many others have also considered the relationship between generalised trust and civic engagement within the context of social capital (Brehm and Rahn, 1997; La Porta, 1997).

However, dispositional trust does not represent a full account of the concept. Many scholars have commented upon the context-dependent nature of trust (Butler, 1991; Hoppner, 2009; Laeequddin, 2010; Peters et al., 1997). Burns et al (2003) argue that:

Some kinds of trust are specific and contingent: trust placed in certain others, under certain circumstances, for certain purposes. The trust we invest in family members is not likely to be the same as the trust we place in people at work, nor should that trust bear much resemblance necessarily to the trust we give to our neighbors.(p. 2)

Hardin (1993: 506) puts it, ’A trusts B to do X’. The ‘X’ – that which the trustee is trusted to be or do – will be referred to as the ‘object’ of trust. Whilst often heard, the statement ‘I trust you’, is rather like stating ‘I hope you’ – it needs to be rooted in a specific context before it has true meaning. The perceived nature of the potential trustee is central to providing this context. An individual may trust their doctor partly on their professional competency as a medic, whereas this is probably not of concern when forming a trust-perception of one’s partner.

Many researchers have suggested, or attempted to determine, the perceived attributes, characteristics and values of a specific ‘other’ which influence feelings of trust (Butler, 1991; Hoppner, 2009; Leahy and Anderson, 2008; Lubell, 2007; Mayer et al., 1995; Peters et al., 1997; Petts, 1998; Poortinga and Pidgeon, 2003). Such studies often refer to these as ‘dimensions’ or ‘bases’ of trustworthiness (or trust). In an influential paper, Mayer et al (1995) suggest that the ability, benevolence and integrity of the trustee are the three core factors. However, many others have argued that the dimensions will vary dependent upon the situation, as will their influence and their acquisition. Central to this variance are the objects of trust. Different dimensions of trustworthiness may underlie the different forms of trust. A student may trust their professor to deliver a useful lecture because they believe them to hold expert knowledge in the field, whereas they may not trust the same individual to return an essay to them on time because they consider them to be disorganised. Different dimensions of trustworthiness (expertise; efficiency) influence different objects of trust (lecturing ability; keeping deadlines). Hoppner (2009) conducted qualitative interviews with residents, determining eight dimensions of trust in a local land-use planning committee: honesty; openness; fairness; reliability; reciprocation; respectfulness; commitment; and shared interests.

Perceptions of another’s trustworthiness may be acquired through direct experience, as might be the case with acquaintances and friends, or through learning of their reputation from a third party (Dasgupta, 2000). The potential trustor may also make generalisations of another’s trustworthiness by stereotyping the trustee based on their gender, occupation or physical appearance, for example (McKnight et al., 1998). They may also trust based upon perceived similarities between themselves and the potential trustee (ibid). Earle and Cvetkovich (1995, cited in Earle and Cvetkovich 1999) developed the concept of ‘salient value similarity’ which posits that those who are perceived to hold similar values may be more likely to trust one another.

A third component of trust is added in this account, based on the work of Russell Hardin (1993; 2006; with Cook et al., 2005) who developed the ‘encapsulated interests’ account of trust, which has also been referred to as ‘institutional trust’ (Dietz, 2011). This suggests that trust is influenced by the potential trustor’s consideration of external incentives and sanctions faced by the potential trustee in a specific situation. Dietz (2011: 216) considers the trust an individual might feel towards a train driver, which stems from the ‘institutional constraints on [the driver’s] options: defiance of the appointed route will be dangerous not only to the driver’s life (and ours as well), but also to her/his career’. The driver and passenger have overlapping interests. Hardin (2006) considers the example of reputation. A trader may be trusted by a customer not only due to their trusting disposition or their perception of the trader’s trustworthiness, but because they are aware that it is in the interests of the trader to be trustworthy. If the trader were to betray the customer’s trust their reputation could be damaged, which would affect their ability to make future sales. The importance of reputation therefore creates shared interests for the trustee and trustor. Note that the incentives and sanctions which may influence trust are outside the control of the trustor – they are not akin to the drawing up of a contract. This would contravene the final clause of the trust definition above, “irrespective of their ability to monitor or control the trustee”. This component of trust will be referred to as ‘situational incentives and sanctions’ (SIS).

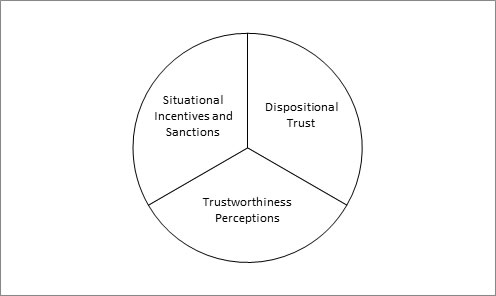

Figure 1 depicts a model of trust which encompasses the three elements described above. The overall trust felt toward a party will be a combination of different components (Mayer et al., 1995). It should be noted that the bearing of each component on overall trust in another party will be dependent upon both the subject and object of trust (Rotter, 1971). For example, when knowledge of both the other party and the situation is weak, one’s disposition to trust may be the most influential element – we extrapolate based on our generalised experiences of others. This contrasts with our feelings toward friends with whom we have many years of interaction. In this situation, individuals may possess a well-informed view of their friends’ trustworthiness in certain domains, making this the most important element, whilst one’s disposition to trust is rendered insignificant. Rotter (1971: 446) puts it simply, ‘the more novel the situation, the greater weight generalized expectancies have.’ The internal lines bounding each component in Figure 1 are therefore frequently adjusted to allow for each element to have a greater bearing on overall trust in another party.

Figure 1: Model of Trust

Trust and participation in urban regeneration

Public participation has increasingly become a favourable policy objective in education, policing, health, housing, town planning and urban regeneration programmes over the last few decades (Brannan et al., 2006). Burton et al(2006) have attempted to pull together the alleged benefits of participation. The two major groupings are of procedural and substantive advantages. The former holds that community involvement is simply a civil right which is deserved regardless of the resultant benefits or disadvantages. The substantive benefits can be divided further into instrumental and developmental advantages. The former holds that programmes will benefit from community’s unique local knowledge and secondly, that initiatives may be afforded greater legitimacy by the public (Ball, 2004). The developmental advantages can be broken down into individual and wider social benefits. The former encapsulates the potentially educative role of participation, which linked to New Labour’s focus on ‘responsibility’ (Barnes et al., 2007) and is shared by the Coalition government (DCLG, 2011). Alcock (2004) considers the claim that communities can benefit as a whole by involvement, through the development of social capital. He argues that for government, ‘social capital [is] a kind of proxy measure for the level of social inclusion and integration within communities’ (ibid: 90). However, social capital has received much criticism for, amongst other things, the wide variance in its definitions and problems surrounding its measurement (Foley and Edwards, 1999; Haynes, 2009), both of which cause difficulties for any participatory policy which sees its development as an aim.

Citizen involvement is especially salient currently, as the government pursues its localism agenda:

Decentralisation will give every citizen the power to participate and change the services provided to them through better information, new rights, greater choice and strengthening accountability via the ballot box. Engagement of the local community can bring benefits for those who get involved and can contribute to more successful outcomes for local communities…individuals and communities will increasingly take responsibility for improving their own area, as part of helping to build the Big Society. (DCLG, 2011, emphasis in original)

The development of trust, either within communities or between citizens and organisations, has often been modelled as a goal of public participation (Bloomfield, 2001; Halvorsen, 2003; Fordham et al., 2009; Hoppneret al., 2007; Schumann, 2010). Bradbury et al(1999) suggest it might be more useful to reconsider this orientation. Indeed, Putnam (2000) suggests trust and participation may have a reciprocal relationship. This paper focuses on trust’s hypothesised influence on participation in urban regeneration projects. It is acknowledged that whilst this article focuses on trust’s potential impact, many other factors are also likely to influence participation. Also, whilst the paper focuses on residents’ willingness to participate, it recognises that local authorities and other organisations may seek to engage a variety of stakeholders’ in participatory processes.

Academics have identified trust as an important factor in resident participation in urban governance (Curry, 2012; Fordham et al., 2009; Gallagher and Jackson, 2008; Hibbit et al., 2001; Lister et al., 2007; Pollock and Sharp, 2012; Russell, 2008). Many have focussed on the relationship between residents and institutions. For example, Mathers et al (2008: 603) believe that to increase participation in regeneration, ‘it may be necessary to change the perception of the delivering organisation and indeed to shift the organising role to a ‘trusted’ body’. Research into the New Deal for Communities (NDC) regeneration programme identified distrust in local housing providers and the NDC itself as reasons for residents’ reluctance to participate (Cole et al., 2004). Others have also noted the role of ‘intra-community’ trust and the relationships between residents (Purdue, 2001). Jarvis et al (2011) identified both a ‘lack of trust between residents and between residents and public agencies’ as partly responsible for a long-standing dearth of community involvement in one regeneration area. This has also been reflected in some British policy documents which refer to the ‘the erosion of trust and confidence that dissuades people who feel let down from getting involved again in the future’ (ODPM, 2006: 54) and encourage organisations to ‘”deliver on the deliverables” to increase trust and engagement’ (ODPM, 2004: 1). Another policy document on participation in governance warns that without greater citizen empowerment, ‘then we will oversee a further erosion of trust and participation in democracy’ (DCLG, 2008: 128), again implicitly suggesting a direct relationship between the two.

Despite the wide usage of the term, very few academics have explored the meaning of trust specifically in relation to public participation in local governance, less still urban regeneration. Trust is often casually bandied about as a ‘monolithic panacea’ (Hoppner, 2009). What is meant by the word trust when researchers suggest it needs to be built to boost engagement? What are the dimensions of trustworthiness which are relevant to participation in an urban regeneration project? What is it that officers or organisations are trusted or not trusted to do?

Furthermore, there seems to be some confusion as to the relationship between trust and participation in local decision making. Whilst many have suggested a positive association, the opposite has also been proposed by researchers working in the field of environmental management. Will Focht and associates argue that trust is associated with less participation in local decision making (Anex and Focht, 2002; Focht and Trachtenberg, 2005). The authors argue that there is an inverse relationship between trust and vigilance. Anex and Focht (2002) put it:

Low trust increases stakeholders’ motivation and willingness to be vigilant to safeguard their interests vis-à-vis others’ interest and thus increases their desire to participate. (p. 869)

This contrasts with stakeholders who possess higher levels of trust and will be more comfortable deferring to others (Focht and Trachtenberg, 2005). These ideas have also been discussed within democratic theory, where the ‘mistrustful-efficacious’ hypothesis for political participation has a long history (Fraser, 1970). Indeed, the importance of institutionalising ‘distrust’ within democratic institutions is well documented (see Hardin, 2006; Kasperson et al., 1999; Sztompka, 1999). The theory’s salience in participatory urban regeneration rests upon the extent to which stakeholders view their involvement as a method of protecting their interests. Trust and control have long been seen as two concepts caught in a balancing act, the latter often being sought when the former is lacking (Das and Teng, 1998). To put it simply the theory asks, “if officers or organisations are trusted, why is there any need to participate?”

The confusion amongst the academic community over the relationship between trust and participation is subliminally epitomised by Warburton (1997). She writes:

Clearly, participation will only be increased, and be more effective, if trust and credibility can be restored by creating new types of relationships between institutions and the public. (p. 32)

Here the author clearly argues that increasing participation depends upon building trust. On the very next page of the same document she appears to contradict herself:

Public distrust of traditional democratic institutions, and their loss of credibility, has led to demands for more participation…from the people…(p. 33)

This appears to create a paradox – the two perspectives appear to hold some internal logic, but it seems that both cannot be true. How can trust both increase and decrease participation?

The small amount of empirical research considering this question does little to dissipate the confusion. Using case studies in brownfields redevelopment, Solitare (2005) does find qualitative evidence to suggest that a lack of trust stimulates citizen participation in governance. Whilst Marquart-Pyatt and Petrzelka (2008) appear to provide quantitative evidence for the low-trust-participation theory, they ask respondents about pastparticipation and current levels of trust, clearly leaving open the possibility that participation has resulted in lower levels of trust, rather than the reverse. Payton et al (2005) finds that whilst trust within a community predicted citizen involvement in a wildlife refuge, trust in the institution did not. Cook et al (2005) have suggested that trust is overstated as a concept and may be less relevant to participation than previously thought. Indeed many of the studies which have specifically aimed to determine an association have failed to identify a relationship in either direction (Dekker, 2007; Duffy et al., 2008; Hoppner et al., 2008; Hoppner, 2009; Koontz, 2005; Raymond, 2006).

Squaring the circle of the trust-participation paradox

When two theories or statements are seen to contradict one another the temptation can be to seek empirical evidence to support one and challenge the other. However, in the case of the trust-participation paradox, it is more useful to consider the problem at a theoretical level. Whenever an individual claims to trust another, whilst they may not communicate it, they have in mind what it is that they trust the other individual to be or to do. In general conversation the objects of trust are often assumed from the context in which the term is discussed. This is the crux of the issue with the trust-participation paradox – the apparent confusion exists due to our poor understanding of the term trust. If the monolithic view of trust is abandoned, the two theories can actually co-exist. The objects of trust are different for each theory.

In the seemingly common-sense view that trust in an institution or its officers encourages participation, the concept centres on the trustee’s willingness or ability to receive the views of the participant. As Solitare (2005: 922) puts it:

…in order to participate, citizens must feel as though the effectors are sincere about sharing the decision-making authority and that effectors will truly listen to citizens’ concerns.

In this context, a trusting individual expects the officers to possess attributes, characteristics or values which suggest they will be influenced by the opinions communicated by the trustor through participation. This will be referred to as ‘receptivity trust’. It makes logical sense to argue that there is a direct relationship between receptivity trust and participation – the more citizens trust officers to take their views on board, the more they will be willing to share them. Even if a resident had extremely high receptivity trust in officers, theoretically this would not, as suggested by the low-trust-participation view, discourage them from participating.

There is another form of trust which could theoretically increase citizens’ willingness to participate. Urban regeneration often occurs over a very long time scale, can cost many millions of pounds and can require the cooperation of a wide variety of organisations, both public and private. Aside from trusting officers and organisations as to whether they will be responsive to their views, residents may also question whether they have theability to bring about such significant changes to a neighbourhood. A resident who believes that they will be listened to may still not participate because they do not believe the scheme will ever really occur – ‘The locals had grown wise to officials presenting them with grand-sounding schemes that mostly came to nothing’ (Fisher, 2009: 20, cited in Pollock and Sharp, 2012). This is quite different to involvement in other forms of local governance or political participation aimed at creating or modifying policies or laws. Citizens are perhaps more likely to see the regeneration of their area as a much more complex task than simply altering existing regulations, for instance. This will be referred to as ‘ability trust’ – a resident’s trust in the ability of officers or an institution to be capable of effectively managing projects and bringing them to fruition.

The ‘alternative’ theory, which posits a negative relationship between trust and participation, draws attention to the extent to which the trustees are seen to represent the interests of the trustor. If an individual does not consider their welfare to be at stake from officers’ plans and work, they may well defer to them and forgo opportunities to participate. If an individual believes that their views are being considered by officers why would they participate? This will be referred to as ‘representative trust’. The more an institution or its officers are trusted to be representative of an individual, the less willing they will be to participate. Even if an individual had exceptionally high representative trust in officers, they may remain unwilling to participate – in fact they may be even more unwilling to do so. It should be noted that representative trust does not refer to the potentialof individuals, groups or institutions to act in a representative manner on behalf of a trustor. This leaves open the possibility that the trusted party requires input from the trustor in order to know in what ways they wish to be represented. Instead, it refers to a belief by the trustor that the trusted party is currently acting or intends to act in a way which is representative of them. Simply put, an individual with high representative trust might say, in reference to a trustee’s behaviour, ‘that’s what I would do if I were you’. Representative trust is closely related to the concept of salient value similarity (SVS) suggested by Earle and Cvetkovich (1995 cited in Earle and Cvetkovich, 1999). The authors argue that trust is based on the similarity of one’s values with another – we trust when another tells ‘stories that interpret the world in the same way they do’ (Earle and Cvetkovich, 1999: 21). It seems reasonable to suggest that SVS is central to representative trust. It may well be the people we feel closest to in our values are those who we feel will automatically account for our views in their work. They see the world the same way as we do.

Levels of each form of trust will be partially dependent upon the extent to which the trustor perceives certain dimensions of trustworthiness in the trustee. Essentially, a different model of trust, as depicted in Figure 1, will exist for each form, as they are each based on a different object of trust. All three forms of trust can co-exist within one overall participation model for urban regeneration. This article posits that receptivity and ability trust have direct relationships with participation whereas representative trust has an inverse relationship with participation. Receptivity trust and representative trust both focus on the views of residents – the former on whether they can be received, the latter on whether they are already represented. Individuals, who feel that their opinions are not currently represented, but who believe that the officers or institutions are both influenceable and able to enact the regeneration plans, will theoretically be those most likely to participate. It is entirely possible that a combination of high receptivity trust and low representative trust, after stimulating participation, is followed by the inverse arrangement. This would occur if individuals feel they have communicated their opinion and believe that officers will take account of their views in their professional behaviour in the future. This article argues that the apparent trust-participation paradox can be resolved by devoting more attention to a theoretical understanding of trust specific to a participatory context. This may be the reason why empirical research has often failed to identify a relationship.

These ideas share some similarities with the concept of ‘critical trust’ (Poortinga and Pidgeon, 2003; Walls et al., 2004). This is defined as a mix of high general trust in a party and a ‘healthy’ scepticism of their intentions. The authors believe that critical trust may be useful in generating involvement from citizens who will be willing to engage in measured interaction with agencies, rather than simply accepting or rejecting policy suggestions. Similarly, this article suggests that participation may be predicted by a mix of trust and distrust.

Conclusion

This article set out to theoretically consider the concept of trust in relation to participation in urban regeneration. Having first fleshed out a model of trust, the paper identified a lack of critical discussion both around the meaning of the term trust in this policy field and its hypothesised positive association with public participation. Conceptually flimsy applications of trust have led to confusion as to both its meaning and role in public participation. Indeed, there appears to be a logical argument which would suggest that building trust between residents and officers would actually lead to a decrease in participation. The paper recommends that researchers working in policy fields which advocate public participation, such as urban regeneration, begin to reconsider the concept of trust in two ways. Firstly, it should be recognised that trust is context-dependent. Both the objects and subjects of trust are of critical importance. Research which only considers a stakeholder’s trust in a generalised ‘other’ and does not explore what this other is trusted to be or do is unlikely to be illuminating. Papers which reflect on who is trusted and what they are trusted to do may be more enlightening. This allows for the second suggestion – that trust should not be considered as intrinsically beneficial or detrimental in efforts to boost public participation. Different forms of trust, which vary dependent upon subject and object, may have different impacts on individuals’ willingness to engage. This paper has begun to outline forms of trust which may be salient in this field. Trusting officers to allow residents to effect change in a participatory process (receptivity trust) or to competently deliver a local project (ability trust) may indeed increase their willingness to participate. However, trusting officers to account for residents’ interests (representative trust) may have the opposite effect. Hence trust may both increase and decrease citizen participation in governance, without creating a paradox. This may provide the first step in broadening the understanding of both policy-makers and organisations which struggle in their efforts to involve the public and feel that building trust offers a solution. Theoretically, building the ‘wrong’ form of trust could result in less participation.

However, many gaps in knowledge remain. Empirical research is now needed to test the above hypotheses and practically explore conceptualisations of trust and their relationship with public participation in governance. A longitudinal approach may be suitable. Finkel and Muller (1998) use panel data in their research into political participation. The authors argue that the approach benefits both from the analysis of actual behaviour, rather than intended or remembered action, and that it ‘allows us to take into account the possibility of dynamic reciprocal relationships between all independent variables and participation’ (ibid: 41). Indeed, research into the relationship between internet connectivity, community participation and place attachment also argues that a longitudinal approach made it ‘possible to control for initial levels and to disentangle the directionality of the effects’ (Mesch and Talmud, (2010: 1107). This may be particularly pertinent when considering trust, which may have a reciprocal relationship with participation. In their longitudinal study into the relationship between generalised trust and social connectedness, Sturgis et al (2012: 2), argue that ‘cross-sectional survey data means that we cannot be sure that the things that appear to be related to trust are the real causes of differences in trust between individuals’. Furthermore, Day et al(2011) highlight the severe lack of longitudinal research into children’s participation in planning and regeneration in particular.

This article also leaves open numerous additional avenues for theoretical enquiry. For example, the author has not considered the dimensions of trustworthiness (honesty, fairness, benevolence, for example) relevant to each of the three forms of trust. It has also refrained from distinguishing between trust in institutions and trust in their officers. Trust within communities and between participating residents also requires greater attention, as does the potential for trust to influence various forms of participation in different ways. More research, both theoretical and empirical, is needed to fully explore the role of trust in participation across a wide range of public policy fields. This may begin to enhance our understanding of a confusing and misunderstood area of the social sciences which has received very little focussed attention, especially in a UK context.

Dominic Aitken, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University, Howard Street, Sheffield, S1 1WB. Email: a8030435@my.shu.ac.uk.

Alcock, P. (2004) Participation or pathology: contradictory tensions in area based policy. Social Policy and Society, 3, 2, 87-96. CrossRef link

Anex, R. and Focht, W. (2002) Public participation in life cycle assessment and risk assessment: a shared need. Risk Analysis, 22, 5, 861-877. CrossRef link

Ball, M. (2004) Cooperation with the community in property-led regeneration. Journal of Property Research, 21, 2, 119-142.CrossRef link

Barnes, M., Newman, J. and Sullivan, H. (2007) Power, Participation and Political Renewal. Bristol: Policy Press.

Bloomfield, D., Collins, K., Fry, C. and Munton, R. (2001) Deliberation and inclusion: vehicles for increasing trust in UK public governance? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 19, 501-513. CrossRef link

Bradbury, J., Branch, K. and Focht, W. (1999) Trust and public participation in risk policy issues, In: Cvetkovich, G. and Lofstedt, R. (Eds) Social Trust and the Management of Risk. London: Earthscan.

Brannan, T., John, P. and Stoker, G. (2006) Active citizenship and effective public services and programmes; how can we know what really works? Urban Studies, 43, 5/6, 993-1008. CrossRef link

Brehm, J. and Rahn, W. (1997) Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science, 41, 3, 999-1023. CrossRef link

Burns, N., Kinder, D. and Rahn, W. (2003) Social Trust and Democratic Politics. In: Mid-West Political Science Association,Annual Meeting Chicago, USA April 2003.

Burton, P., Goodlad, R. and Croft, J. (2006) How would we know what works?: Context and complexity in the evaluation of community involvement. Evaluation, 12, 3, 294-312. CrossRef link

Butler, J. (1991) Toward understanding and measuring conditions of trust: evolution of a conditions of trust inventory. Journal of Management, 17, 3, 643-663. CrossRef link

Cole, I., Hickman, P. and Mccoulough, E. (2004) The involvement of NDC residents in the formulation of strategies to tackle low demand and unpopular housing Research Report 40. Sheffield: Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research.

Coleman, J. (1990) The Foundations of Social Theory Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press.

Cook, K., Hardin, R. and Levi, M. (2005) Cooperation Without Trust? New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Currall, S. and Judge, T. (1995) Measuring trust between organizational boundary role persons. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 64, 2, 151-170. CrossRef link

Curry, N. (2012) Community participation in spatial planning: exploring relationships between professional and lay stakeholders.Local Government Studies, 38, 3, 1-22. CrossRef link

Das, T.K. and Teng, B.S. (1998) Between Trust and Control: Developing Confidence in Partner Cooperation in Alliances. The Academy of Management Review, 23, 3, 491-512. CrossRef link

Dasgupta, P. (2000) Trust as a Commodity, In: Gambetta, D. (ed.) Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, Chapter 4, p49-72 [online] Last accessed 28 August 2012 at:

https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=http%3A%2F%2Fcsee.umbc.edu%2F~msmith27%2Freadings%2Fpublic%2Fdasgupta-1988a.pdf

Day, L., Sutton, L. and Jenkins, S. (2011) Children and Young People’s Participation in Planning and Regeneration. CRSP [Centre for Research in Social Policy].

DCLG [Department for Communities and Local Government] (2008) Communities in Control: Real people, real power. TSO: Norwich.

DCLG [Department for Communities and Local Government] (2011) Department for Communities and Local Government Select Committee: Regeneration evidence [online] Last accessed: 24-08-2012 at:

http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmselect/cmcomloc/writev/regeneration/m54.htm

Dekker, K. (2007) Social capital, neighbourhood attachment and participation in distressed urban areas. A case study in The Hague and Utrecht, the Netherlands. Housing Studies, 22, 3, 355-379. CrossRef link

Dietz, G. (2011) Going back to the source – why do people trust each other? Journal of Trust Research, 1, 2, 215-222. CrossRef link

Duffy, B., Vince, J. and Page, L. (2008) Searching for the Impact of Empowerment. Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute.

Earle, T. and Cvetkovich, G. (1999) In: Cvetkovich, G. and Lofstedt, R. (Eds) (1999) Social trust and the management of risk. London: Earthscan.

Edelenbos, J. and Klijn, E.H. (2007) Trust in complex decision-making networks: a theoretical and empirical exploration. Administration and Society, 39, 25-5. CrossRef link

Finkel, S. and Muller, E. (1998) Rational choice and the dynamics of collective political action: evaluating alternative models with panel data. American Political Science Review, 92, 1, 37-49.CrossRef link

Focht, W. and Trachtenberg, Z. (2005) A trust-based guide to stakeholder participation, In: Sabatier, P., Focht, W., Lubell, M., Trachtenberg, Z., Vedlitz, A. and Matlock, M. (Eds) Swimming Upstream: Collaborative Approaches to Watershed Management.Cambridge: MIT Press.

Foley, M. and Edwards, B. (1999) Is it time to disinvest in social capital? Journal of Public Policy, 19, 2, 141-173. CrossRef link

Fordham, G., Ardron, R., Batty, E., Clark, C., Cook, B., Fuller, C., Meegan, R., Pearson, S. and Turner, R. (2009) Improving outcomers? Engaging local communities in the NDC programme. Some lessons from the New Deal for Communities Programme.Wetherby: Communities and Local Government.

Fraser, J. (1970) The mistrustful-efficacious hypothesis and political participation. Journal of Politics, 32, 444-449. CrossRef link

Gallagher, D.R. and Jackson, S.E. (2008) Promoting community involvement at brownfields sites in socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 51, 5, 615-630. CrossRef link

Giddens, A. (1990) The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity.

Gillespie, N. (2003) Measuring Trust in Working Relationships: The Behavioral Trust Inventory. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Seattle, WA.

Halvorsen, K. (2003) Assessing the effects of public participation.Public Administration Review, 63, 5, 535-543. CrossRef link

Hardin, R. (1993) The street level epistemology of trust. Politics and Society, 21, 4, 505-529. CrossRef link

Hardin, R. (2006) Trust. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Haynes, P. (2009) Before Going Any Further with Social Capital: Eight Key Criticisms to Address. Valencia: Ingenio.

Hibbitt, K., Jones, P. and Meegan, R. (2001) Tackling social exclusion: the role of social capital in urban regeneration on Merseyside – from mistrust to trust? European Planning Studies, 9, 2, 141-161. CrossRef link

Hoppner, C., Frick, J. and Buchecker M. (2007) Assessing psycho-social effects of participatory landscape planning. Landscape and Urban Planning, 83, 196-207. CrossRef link

Hoppner, C., Frick, J. and Buchecker, M. (2008) What drives people’s willingness to discuss local landscape development?Landscape Research, 33, 5, 605-622. CrossRef link

Hoppner, C. (2009) Trust – A monolithic panacea in land use planning? Land Use Policy, 26, 4, 1046-1054. CrossRef link

Jarvis, D., Berkeley, N. and Broughton, K. (2011) Evidencing the impact of community engagement in neighbourhood regeneration: the case of Canley, Coventry. Community Development Journal, 1-16.

Kasperson, R., Golding, D. and Kasperson, J. (1999) Risk, trust and democratic theory. In: Cvetkovich, G. and Lofstedt, R. (Eds)Social Trust and the Management of Risk. London: Earthscan.

Koontz, T. (2005) Why participate? The collective interest model and citizen participation in watershed groups. Presented at the American Political Science Association annual meeting, Washington DC.

Kramer, R. (1999) Trust and distrust in organizations: emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology,50, 569-598. CrossRef link

Kumar, A. and Paddison, R. (2000) Trust and collaborative planning theory: the case of the Scottish planning system.International Planning Studies, 5, 2, 205-223. CrossRef link

La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. (1997) Trust in large organizations. The American Economic Review, 87, 2, 333-338.

Laeequddin, M., Sahay, B.S., Sahay, V. and Waheed K.A. (2010) Measuring trust in supply chain partners’ relationships. Measuring Business Excellence, 14, 3, 53-69. CrossRef link

Leahy, J. and Anderson, D. (2008) Trust factors in community-water resource management agency relationships. Landscape and Urban Planning, 87, 100-107. CrossRef link

Li, P.P. (2007) Towards an interdisciplinary conceptualization of trust: a typological approach. Management and organization review, 3, 3, 421-445. CrossRef link

Lister, S., Perry, J. and Thornley, M. (2007) Community Engagement in Housing-led Regeneration: A Good Practice Guide. Coventry: Chartered Institute of Housing.

Lubell, M. (2007) Familiarity breeds trust: collective action in a policy domain. The Journal of Politics, 69, 1, 237-250. CrossRef link

Marquart-Pyatt, S. and Petrzelka, P. (2008) Trust, the democratic process, and involvement in a rural community. Rural Sociology,73, 2, 250-274. CrossRef link

Mathers, J., Parry, J. and Jones, S. (2008) Exploring resident (non-)participation in the UK New Deal for Communities regeneration programme. Urban Studies, 45, 3, 591-606.CrossRef link

Mayer, R., Davis, J. and Schoorman, F.D. (1995) An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review,20, 3, 709-734. CrossRef link

Mcknight, D., Harrison, Cummings, L. and Chervany, N. (1998) Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships.Academy of Management Review, 23, 3, 473-490.

Mesch, G. and Talmud, I. (2010) Internet connectivity, community participation, and place attachment: a longitudinal study.American Behavorial Scientist, 53, 8, 1095-1110. CrossRef link

Metlay, D. (1999) Institutional trust and confidence: A journey into a conceptual quagmire, In: Cvetkovich, G. and Lofstedt, R. (Eds)Social Trust and the Management of Risk. London: Earthscan.

ODPM [Office of the Deputy Prime Minister] (2004) Empowering Communities, Improving Housing: Involving black and minority ethnic tenants and communities. London: ODPM.

ODPM [Office of the Deputy Prime Minister] (2006) Promoting effective citizenship and community empowerment. London: ODPM.

Payton, M., Fulton, D. and Anderson, D. (2005) Influence of place attachment and trust on civic action: a study at Sherburne National Wildlife Refuge. Society and Natural Resources, 18, 511-528. CrossRef link

Peters, R., Covello, V. and Mccallum, D. (1997) The determinants of trust and credibility in environment risk communication: an empirical study. Risk Analysis, 17, 1, 43-54. CrossRef link

Petts, J. (1998) Trust and waste management information expectation versus observation. Journal of Risk Research, 1, 4, 307-320. CrossRef link

Pollock, V.L. and Sharp, J. (2012) Real participation or the tyranny of participatory practice? Public art and community involvement in the regeneration of the Raploch, Scotland. Urban Studies [online] Last accessed on 28 August 2012 at:http://usj.sagepub.com/content/early/2012/04/02/0042098012439112

Poortinga, W. and Pidgeon, N. (2003) Exploring the dimensionality of trust in risk regulation. Risk Analysis, 23, 5, 961-972.CrossRef link

Purdue, D. (2001) Neighbourhood governance: leadership, trust and social capital. Urban Studies, 38, 12, 2211-2224. CrossRef link

Putnam, R. (2000) Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Putnam, R. (2001) Social capital: Measurement and consequences, In: Helliwell, J. (Eds) The contribution of human and social capital to sustained economic growth and well-being(pp. 117–135). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Human Resources Development Canada.

Raymond, L. (2006) Cooperation without trust: Overcoming collective action barriers to endangered species protection. The Policy Studies Journal, 34, 1, 37-57. CrossRef link

Rotter, J. (1971) Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trust.American Psychologist, 26, 5, 443-452. CrossRef link

Rousseau, D., Sitkin, S., Burt, R. and Camerer, C. (1998) Not so different after all: a cross discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 3, 393-404. CrossRef link

Russell, H. (2008) Community Engagement: Some lessons from the New Deal for Communities Programme. London: CLG.

Schumann, S. (2010) Application of participatory principles to investigation of the natural world: an example from Chile. Marine Policy, 34, 1196-1202. CrossRef link

Solitare, L. (2005) Prerequisite conditions for meaningful participation in brownfields redevelopment. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 48, 6, 917-935.CrossRef link

Sturgis, P., Patulny, R., Allum, N. and Buscha, F. (2012) Social Connectedness and Generalized Trust: A Longitudinal Perspective.Colchester: Institute for Social & Economic Research.

Sztompka, P. (1999) Trust: A Sociological Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vangen, S. and Huxham, C. (2003) Nurturing collaborative relations: Building trust in interorganizational collaboration. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39, 5, 5-31. CrossRef link

Walker, G., Devine-Wright, P., Hunter, S., High, H. and Evans, B. (2010) Trust and community: exploring the meanings, contexts and dynamics of community renewable energy. Energy Policy, 38, 6, 2655-2663. CrossRef link

Walls, J., Pidgeon, N., Weyman, A. and Horlick-Jones, T. (2004) Critical trust: understanding lay perceptions of health and safety risk regulation. Health, Risk and Society, 6, 2, 133-150. CrossRef link

Warburton, D. (1997) Participatory Action in the Countryside: A Literature Review. Countryside Commission.

Weil, F. (1986) The stranger, prudence and trust in Hobbes’s theory. Theory and Society, 15, 5, 759-788. CrossRef link