Abstract

In recent years, universities in the UK have increased efforts to promote diversity and equality in their institutions. Such efforts include establishing partnerships with schools and colleges in local communities (Russell Group, 2023), creating mentorship programmes (SHU, 2022), attempting to decolonise the curriculum (HEPI, 2020), funding research to address the ethnic minorities awarding gap (OFS, 2021), and providing ringed-fenced scholarships for Black and mixed heritage students (Sucharitkul and Windsor, 2021). These interventions are directly aimed at widening access and participation for under-represented groups. Nevertheless, there remains a significant amount of work to be done in supporting improvements in the progression and outcomes for minoritised students in universities, especially those from Black and mixed-Black ethnic backgrounds.

In September 2019, Leading Routes (2019) produced a ground-breaking report on Black students’ access to postgraduate research programmes and race-based inequalities within Higher Education in the UK. Citing figures from Higher Education Statistics Agency, (HESA), the report revealed that in 2017/18, out of 15,560 full-time UK domiciled PhD students in their first year of study, just three per cent of those students were Black (HESA, 2019).

The Leading Routes (2019) report highlighted three key factors influencing Black PhD students’ decision-making and application process. First, there is an emphasis on prior attainment – which disadvantages Black students who are the least likely to achieve a ‘good undergraduate degree’ (upper second-class or first-class honours) (Universities UK, 2019). Second, the preference for graduates from research-intensive institutions was highlighted. This is important because Black students are more likely to attend post-92 universities (Boliver, 2016). In addition, applicants who have attended Russel Group institutions are regularly favoured over post-92 universities in determining funded PhD places. Thirdly, almost half of all Black doctoral students are enrolled part-time, the most significant percentage of part-time PhD students across all ethnic groups, and part-time students are more likely to be self-funded. (Leading Routes, 2019).

While over the last two decades, there has been significant progress in increasing access for Black and other ethnic minoritised groups (Pimblott, 2020; Sucharitkul and Windsor, 2021), there is a concerted effort at play to increase the representation of Black and mixed-Black heritage students in postgraduate and research level degrees (Pimblott, 2020). One such effort is the deliberate action of increasing access to Black heritage students through ring-fencing of scholarship slots at postgraduate and research study levels (Sucharitkul and Windsor, 2021).

To address the underrepresentation of Black students and other ethnic minority groups at PhD level, the Office for Students (OFS) funded 13 projects to increase access and participation for Black, Asian and Minority ethnic groups in the postgraduate research study. One of the funded projects is the Accomplished Study Program in Research Excellence (ASPIRE).

This article will provide an overview of the literature on the history of racism in higher education in the UK, focusing on postgraduate research education, and provide insight and evidence from the ASPIRE programme on how a personalised mentorship program has the potential to make a difference in widening participation for Black students.

A brief history of racism in higher education – slavery, colonialism and discrimination of ethnic minority students

Racism in higher education in the UK has a long history, dating back several centuries. While it is challenging to pinpoint the earliest indication, notable historical events that shaped racial discrimination include the Trans-Atlantic slave trade (15th to 19th century) and colonialism (19th to 20th century). The trans-Atlantic slave trade, which began as early as the 15th century, introduced a system of slavery that was racialised (Barker, 1978; Drescher, 1990). Forced labour has been common throughout history – Africans and Europeans had been trading goods and people across the Mediterranean for centuries. However, enslavement had not been based on race. What was different about the trans-Atlantic slave trade was that enslaved people were seen not as people but as commodities to be bought, sold and exploited (Barker, 1978).

When slavery ended in the British Empire between 1834 and 1838, slaveholders received £20 million in compensation for the loss of their ‘property’ (Draper, 2010). In the 2000s, a historian at UCL called Nick Draper, through a large research project on the Legacies of British Slave Ownership, began to follow the money, and track who received compensation (University College London, 2023) The project showed that the foundation of some of the most prestigious universities in the UK was marred with money connected to slavery. For instance, King’s College London was established through financial contributions and the acquisition of £100 subscription “shares” from affluent Anglicans. These donations amounted to approximately £50,000 by the end of 1828, comprising nearly half of the funds required to construct the universities iconic King’s Building by 1831. It has since come to light that a noteworthy portion of these benefactors were individuals who had amassed wealth through the ownership and exploitation of enslaved persons in the West Indies. Overall, Draper estimates that somewhere above ten per cent of the founding subscriptions to King’s College London were directly named recipients of slave compensation after 1834. (Draper, 2010).

Similar patterns can be seen in other parts of the Western world. The history of North American universities demonstrates that the institution was founded by missionary and settler projects engaged in the genocide of indigenous peoples who lived in the region. (Thobani, 2022: p. 11) This history also shows how universities became crucial in consolidating regimes of violence dispossession, and enslavement that tied North America to Europe, Africa and Asia. (Thobani, 2022: p. 11).

In recent years, studies have argued that universities in the Western world continue to maintain the racial hierarchies they were built on, embedded in colonial ideologies that reproduce ‘whiteness’. Thobani (2022: p. 5) argues that the ‘Western university’ is productive of the racial-colonial hierarchies that structure nation, state, and capital within local and global contexts. According to Bhopal (2014: p. 19), being white entails inherent advantages in society through ‘the maintenance of power, resources, accolades and systems of support through formal and informal structures and procedures’. Wong et al. (2022) maintain that whiteness does not have to be embodied by a white person; it could be a non-white person too, and universities are symbolically centres of whiteness.

Wong et al. (2022) further discuss the prevalence of whiteness in higher education, its implications on ethnic minority students and examine the student approaches and coping strategies to racism. Drawing on sociological and psychological literature to analyse over 51 in-depth interviews of minority ethnic undergraduates in England, in response to concerns over the ethnicity degree awarding gap, the study found emotional detachment to be prominent in confronting white privilege and racism in university spaces (Wong et al., 2022). These experiences are also felt by Black academics. Johnson and Joseph-Salisbury (2018) consider what it means to study race(ism) in the ‘everyday’ whilst being subjected to everyday racism within academia. By centring their experiences, they point to the pervasiveness of white supremacy within the academy and explore the potential to challenge the legitimacy of the academy as the legitimate space of knowledge production.

In the United States and South Africa, there have been radical responses to racism and unequal treatment faced by ethnic minority students in Higher Education. Specifically, affirmative action has been employed as a policy approach to promote equal opportunities and address historical disadvantages faced by marginalised groups, particularly in the context of employment or education. In the United States, the literature on affirmative action in higher education focuses on examining the rationale, impact, and controversies surrounding the policy approach. Kellough’s (2006) comprehensive work provides an overview of affirmative action policies and their legal, political, and social dimensions. While it covers various contexts, it also discusses the implications of affirmative action in higher education. Urofsky (2020) explores the historical development of affirmative action in the United States, tracing its roots to the Reconstruction era and examining its impact on postgraduate education. Sander and Taylor (2012) explore the impact of affirmative action on college and professional school admissions, discussing the potential harmful effects on student performance and suggesting alternative policies.

The literature on affirmative action from South Africa explores similar themes as the United States, including the implementation, impact, and challenges associated with affirmative action policies in the country’s higher education system. The legacy of apartheid and racial inequalities in the country continues to shape conversations and actions surrounding racism in higher education. While significant progress has been made since the end of apartheid, challenges persist, particularly in the education system. Organisations such as the National Association of Democratic Lawyers (NADEL) and the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) work to address racism faced by Black students, advocate for their rights and equality, and promote the implementation of affirmative action.

Notable academic works that make the case for affirmative action as a means to address historical inequalities include Vasti Roodt and Karin van Marle’s collection of essays which explores various aspects of race, diversity, and curriculum transformation in South African higher education, including the effectiveness of affirmative action. (Roodt and Van Marle, 2016). Other studies have addressed the broader issues of affirmative action in South African universities, examining its impact on employment practices and the experiences of faculty and staff. This section has scoped the scholarly literature on the history of racism in higher education, emphasising the impact of colonialism on racism in present-day universities. The following section will discuss how universities have responded to this issue.

Institutional action: Response to demands for equity in Higher Education

Universities have responded to demands for equity and access in different ways, which include anti-racist statements, calls for decolonisation and pledge for reparation (University of Glasgow, 2019). Some universities have launched funded doctoral schemes targeted at applicants from Black and other under-represented ethnic minority groups.1 These schemes reflect an awareness of the additional challenges and barriers faced by applicants from ethnic minorities backgrounds in successfully accessing PhD programmes and funding.

Recognising the need for action, the Office for Students (OFS) and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) launched a funding competition to increase access and participation for Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups in postgraduate research studies in 2020. 13 projects were funded due to this call. One of the 13 projects funded is ASPIRE, which is making an impact in the lives of Black scholars who have participated in the program. The remaining sections of this article will provide evidence of the success recorded by the ASPIRE program in widening participation at the doctoral level for Black students and how universities in the UK can adopt the model.

Accomplished Study Program in Research Excellence (ASPIRE)

ASPIRE is an innovative tripartite program led by Sheffield Hallam University in partnership with Manchester Metropolitan University and Advance HE. The programme is designed by Black academics for Black students, and centres on health, well-being, and compassionate conversations to build the confidence of Black and Mixed-Black heritage students interested in doctoral study. It is also reciprocal in that it also develops the supervisory teams’ understanding of the often-taboo subject of race and its importance to the ‘Black experience’.

The ASPIRE funding spans from 2021 to 2025, aiming to conduct three cycles of a mentorship program over the project’s duration. Currently, the project has successfully concluded its second cohort.

The project is designed to develop the capabilities of Black students to navigate structural barriers to doctoral study and enhance pathways of opportunity through inclusive targeting.

The four key aims of the project are:

- Develop an impactful, inclusive, targeted research mentorship and well-being programme designed to meet the racialised needs of Black students interested in the doctoral-level study.

- Evaluate how structural barriers to access doctoral-level study for Black students can be overcome through participation in ASPIRE.

- Determine whether participation in ASPIRE leads to improved work-readiness of Black students to access doctoral-level study.

- Improve the understanding of postgraduate research (PGR) supervisors of the specific, racialised needs of Black students interested in accessing doctoral study and how Black students can be best supported.

ASPIRE is a six-month programme of exciting, interesting and thought-provoking weekly workshops, activities & synchronous and asynchronous classes. These classes cover professional & personal development, academic writing, employability, research skills (quantitative and qualitative) and project management, which are the five core pillars of ASPIRE. The programme places an emphasis on compassionate pedagogy, which means that the teaching practices are compassionate and focus on scholars as unique individuals and their unique experiences and needs.

In addition to the weekly learning activities that scholars engage in, they also have the opportunity to undertake a paid 30-hour internship (ASPIRE 30) with an employer. The internships available on ASPIRE 30 span a wide range of sectors, including STEM, business, education, arts and humanities. At the end of the ASPIRE programme, scholars undertake a six week research project to enhance their employability skills and doctoral-level study.

Scholars also develop an e-portfolio of evidence that can be used to create personalised websites to showcase their developing skills and achievements to potential employers and Universities offering PhD places. Each scholar is assigned a Black academic who mentors them throughout the duration of the program and a White or Asian academic supervisor for their six-week project.

ASPIRE evaluation method

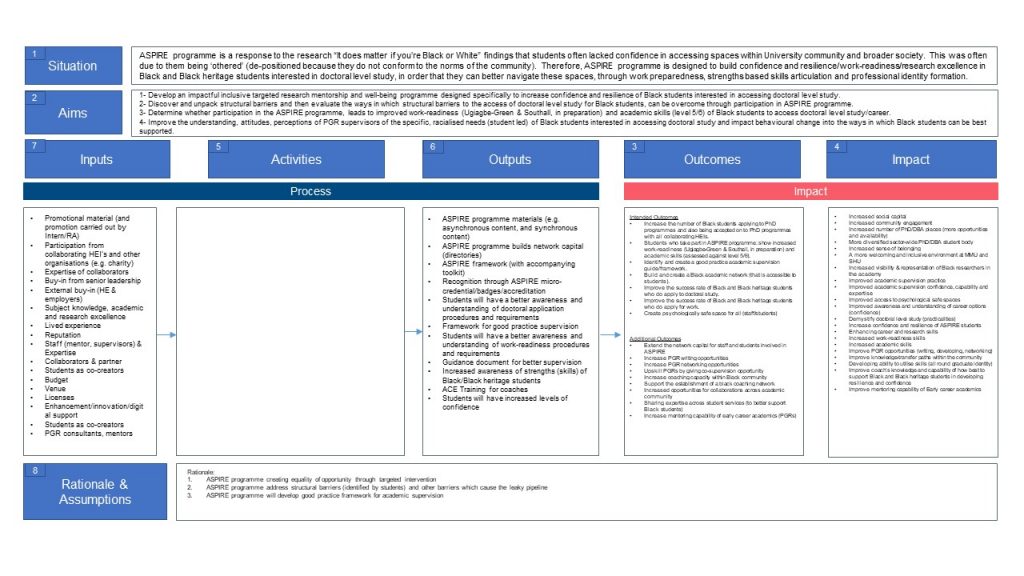

The evaluation of ASPIRE is structured around the Theory of Change (ToC) framework, which encompasses four key stages: diagnosis, planning, measurement, and reflection. These stages were meticulously followed to establish a logical model that outlines the program’s objectives, the desired changes it seeks to achieve, including outcomes and impacts as shown in Figure 1, and the strategies it employs to attain these goals. The assessment consists of two main components: an impact evaluation aimed at gauging improvements in students’ experiences, engagement, and their prospects for future studies or careers, and a process evaluation that scrutinises the nature and quality of program implementation. The project evaluation design is a collaboration between the ASPIRE project team and Advance HE, with Advance HE taking the lead role.

Figure 1: Theory of Change Logic model for ASPIRE

The evaluation period encompasses the entire project timeline. Advance HE generates annual reports to facilitate the project team in gauging its impact and identifying any necessary adjustments. The final project report is anticipated to be delivered in 2026.

Insights and discoveries from the initial evaluation report empower the project team to enact modifications to the second cohort’s delivery, a practice also slated for the third cohort. For instance, the evaluation process revealed disengagement among both scholars and academic supervisors during the summer months. This observation guided us in adapting the program’s schedule to ensure that each cycle concludes in June with a showcase event in early July.

Impact of the ASPIRE on Participating Scholars, Mentors and Supervisors

Preliminary indications suggest that the program is positively influencing the academic experiences and self-confidence of scholars who are taking part in the program’s first year (2021/22, 30 Black students were supported through personalised mentorships delivered by Black academics. A further 16 scholars were supported in the second year (2022/23). At the end of the year, as evidenced by the ASPIRE showcase event and the qualitative data collected, the scholars expressed growth in confidence and self-belief. The showcase event allowed the scholars to share their ASPIRE journey through poetry, affirmation banners and other artefacts they created as part of the ASPIRE programme. The programme’s impact was such that the scholars saw themselves as ‘tenacious, brave, courageous and resilient’.

The ASPIRE programme has also improved the perceived future study or career prospects of scholars. The survey data collected at the start of the ASPIRE programme indicated that scholars lacked confidence and rated their skills as lesser than their peers (lower than the control group (n=24)). However, by the end of the programme, all the scholars (n=17) who were interviewed and those who completed the post-survey (n=15) indicated that they were either applying for doctoral study or graduate employment. Shared experience was important to scholars and these experiences facilitated discussions about applying for a PhD. For example, a scholar shared that:

The last time she [the scholar’s mentor] called me she asked me if I was interested in a PhD and I told her I have my excuse to it, that for now it’s not something I want to consider and the reason being that I have three boys. Back home I’ve always been a working lady. She [the scholar’s mentor] called me later and she told me that it [the PhD] will give me more time if I consider it an option that it would be nice if I do it, that it will give me more time for the kids, to have with them (Scholar, 2022).

Many scholars mentioned the importance of having a shared lived experience with their mentor and the novelty of working with a Black member of staff at the university. In the words of one of the scholars, she said:

I think because, well, with my mentor, having a Black mentor, again, I’m not used to working with any Black members of staff or, you know, at university and so on. So having someone who can really relate to me and understand me, you know, from that perspective, made all the difference. There was a lot of things that I knew she understood without me having to explain and unpick (Scholar, 2022).

Five scholars from the programme have already started their PhDs at Sheffield Hallam University and Manchester Metropolitan University. Further four scholars are due to start their PhDs at Sheffield Hallam University, the University of Durham and the University of Leeds. Another three scholars graduated as the overall best students (based on performance across all modules studied) in their PG programs at Sheffield Hallam University. Two of our scholars completed MA programmes in the 2022/23 academic year, and the ASPIRE program so inspired one of our scholars who never thought of going into teaching and has completed a Post Graduate Course in Chemistry at MMU.

One of the scholars who did not consider herself a conventional academic student received an unconditional PhD offer. She described ASPIRE’s impact on her academic journey:

The ASPIRE programme has so far benefitted me a lot in the short space of time I have had the opportunity to engage with it. It has given me confidence about my future path career and assured me that I am really not alone. Something I used to worry about a lot (Scholar, 2023).

I want to personally thank you for your support. I have received an unconditional offer to pursue a PhD at Leeds University and all thanks to ASPIRE. I know for certain this would not be the case had I not joined the programme last year. The immense support we received, the talks, the community was just what I needed to believe in myself, that I am capable of achieving my goals. As you know, I am unconventional, not your typical student due to family commitments among other responsibilities, and ASPIRE really helped me to dig deep and challenge myself. This is truly an amazing programme and well done and thank you for taking the step to ensure people like me can finally be a Dr one day, and contribute to making this world a better place (Scholar 2022).

This message strongly illustrates ASPIRE’s transformative impact, particularly through its support and inclusive community. The scholar attributes their successful PhD offer at Leeds University to ASPIRE, citing its vital role and the program’s encouragement in helping them overcome unconventional challenges. Overall, the message underscores the program’s profound positive influence and its role in supporting diverse individuals on their academic paths, contributing to a brighter future.

The programme has also impacted participating mentors and supervisors. In the words of one of the mentors on the programme, she said:

Undertaking the role of mentor and co-supervisor has helped my personal development as a lecturer, particularly in providing support to students from ethnic minorities. As a result of my involvement in ASPIRE, I now follow up with Black students to understand the challenges they may face as students from ethnic minorities and direct them to available support (Mentor, 2022).

Another mentor said:

Working with Black and mixed-Black heritage students under the ASPIRE project has been a privilege and a rewarding experience. While a logical expectation is to see the mentees thrive with the benefit of one’s interaction within and outside the academic space, what strikes me more is the add-on effect of learning from the mentees themselves. The relationships fostered has gone beyond the ASPIRE program. I now have a deeper understanding of the unconscious constraints that tends to limit Black and mixed-Black heritage students’ academic engagement. With this understanding, my zest for a more inclusive and culturally tolerant interaction has been rewarded with higher attendance and participation in classroom activities by my students (Mentor, 2023).

An academic supervisor who participated in the programme said:

I actually found the face-to-face sessions really helpful […] you needed that interaction and also that, for me, a kind of safe environment to say things that maybe you wouldn’t necessarily say otherwise (Supervisor, 2022).

This evidence as shown the wider impact of the ASPIRE programme in not only creating access and participation for Black and Mixed-Black heritage scholars in the UK but in also in shaping the teaching practices of participating mentors and supervisors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article delves into the critical issue of racial inequality and discrimination within higher education in the UK, particularly focusing on postgraduate research programs. It outlines a historical backdrop of racism, drawing connections to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, colonialism, and the legacy of such events, revealing the presence of these issues even in the founding of prestigious universities.

The article also highlights the pervasive impact of racism within higher education, addressing the notion of ‘whiteness’ and its influence on academia. It emphasises that universities continue to perpetuate racial hierarchies and colonial ideologies, thus maintaining structural inequalities.

In response to these challenges, universities have taken various measures, including affirmative action policies and targeted scholarship programs. The article provides an overview of the ASPIRE programme, an initiative designed to empower Black students interested in pursuing doctoral-level studies. It details the program’s objectives, the impact it has had on participants, mentors, and supervisors to date, and its role in helping to foster confidence, resilience, and future career prospects for Black scholars.

The program’s unique approach, focusing on compassionate pedagogy and shared experiences, has generated a sense of empowerment and belonging among its participants based on the emerging findings from the program.

The ASPIRE programme is on-going and will run until 2025. Whilst more evidence will emerge on the longer-term impacts of the programme, the initial evidence reported here points to a programme that has transformative potential for the experiences of black and mixed heritage scholars. This article has underscored the importance of ongoing efforts to dismantle racial hierarchies in higher education, advocating for equity and access for all students. The ASPIRE programme signifies a promising step towards addressing the historical racial inequalities that have persisted within academia. ASPIRE serves as a compelling example of how universities should seek to create inclusive and diverse academic environments, ultimately working towards a more equitable and just future for all students, regardless of their racial or ethnic background.

1 Examples are: Black Academic Futures at Oxford, James McCune Smith PhD Scholarships in Glasgow, the Diversity100 PhD Studentships at Birkbeck, The Yorkshire Consortium for Equity in Doctoral Education and King’s Harold Moody Scholarships.

Ifedapo Francis Awolowo, Sheffield Business School, Sheffield Hallam University, Howard Street, Sheffield. S1 1WB. Email: i.f.awolowo@shu.ac.uk

Barker, A. J. (1978) The African Link: British Attitudes to the Negro in the Era of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Frank Cass.

Bhopal, K. (2014) The experiences of BME academics in higher education: Aspirations in the face of inequality: Stimulus paper. Leadership Foundation for Higher Education. Available at: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/364309/1/__soton.ac.uk_ude_personalfiles_users_kb4_

mydocuments_Leadership%2520foundation%2520paper_Bhopal%2520stimuls%2520paper%2520final.pdf

Boliver, V. (2016) Exploring Ethnic Inequalities in Admission to Russell Group Universities. Sociology, 247-266. CrossRef link

Draper, N. (2010) The Price of Emancipation: Slave-Ownership, Compensation and British Society at the end of slavery.

Drescher, S. (1990) The Ending of the Slave Trade and the Evolution of European Scientific Racism. Social Science History, 415-450. CrossRef link

Elliott, M. and Hughes, J. (2019) Four hundred years after enslaved Africans were first brought to Virginia, most Americans still don’t know the full story of slavery. New York Times Magazine, 19 August. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/19/magazine/history-slavery-smithsonian.html

HEPI (2020) New report calls for the decolonisation of universities in order address a ‘silent crisis’. Available at: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2020/07/23/new-report-calls-for-decolonisation-of-universities-in-order-address-the-silent-crisis-in-universities/

HESA. (2019) Higher Education Student Statistics: UK, 2017/18 – Student numbers and characteristics. Higher Education Statistics Agency.

Johnson, A. and Joseph-Salisbury, R. (2018) ‘Are you supposed to be in here?’ Racial microaggressions and knowledge production in higher education: Racism, whiteness and decolonising the academy. In: J. Arday and H. S. Mirza (eds.) Dismantling race in higher education: Racism, whiteness and decolonising the academy. Palgrave Macmillan: pp. 143-160. CrossRef link

Kellough, J. E. (2006) Understanding Affirmative Action: Politics, Discrimination, and the Search for Justice. Georgetown University Press.

Leading Routes (2019) The Broken Pipeline : Barriers to Black PhD Students Accessing Research Council Funding. Leading Routes.

Roodt, V. and van Marle, K. (eds.) (2016) Race and Curriculum: Educating for Diversity in a Global Age.

OFS (2021) Degree-awarding gaps: a targeted approach. Available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/promoting-equal-opportunities/effective-practice/degree-awarding-gaps-a-targeted-approach/

Pimblott, K. (2020) Decolonising the University: The Origins and Meaning of a Movement. The Political Quarterly, 19, 1, 210-216. CrossRef link

Russell Group (2023) Supporting local schools. Available at: https://russellgroup.ac.uk/policy/case-studies/supporting-local-schools/

Sander, R. and Taylor Jr., S. (2012) Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It’s Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won’t Admit It. Basic Books.

SHU (2022) First cohort graduate from programme to support black students towards doctoral-level study. Available at: https://www.shu.ac.uk/news/all-articles/latest-news/aspire

Sucharitkul, P.J. and Windsor, L. (2021) Widening Participation in Post-Graduate Teaching and Research. Leeds: University of Leeds.

Thobani, S. (Ed.) (2022) Coloniality and racial (in)justice in the University: Counting for Nothing? CrossRef link

Universities UK (2019) Black, Asian And Minority Ethnic Student Attainment At Uk Universities: #Closingthegap. Universities UK.

University College London (2023) Legacies of British Slavery. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/

University of Glasgow (2019) Historic Agreement Sealed Between Glasgow And West Indies Universities. Available at: https://www.gla.ac.uk/news/archiveofnews/2019/september/headline_667960_en.html

Urofsky, M.I. (2020) The Affirmative Action Puzzle: A Living History from Reconstruction to Today. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Wong, B., Copsey-Blake, M. and ElMorally, R. (2022) Silent or silenced? Minority ethnic students and the battle against racism. Cambridge Journal of Education, 52, 5, 651-666. CrossRef link