Abstract

Using Elias’ thoughts on the informalisation of parenting (where authoritarian parenting is discouraged and the autonomy of children is encouraged) and relational parenting (parents must think about the effects of their parenting style on the emotions of children) as a starting point, this article discusses the intensification of these parenting techniques as ‘best practice’, particularly since 1997. However, there has been a reformalisation of ‘parenting’ between the state and parents; policy surrounding parenting best practice and regulation of families are underlined by sanctioning and formalised interventions if there is no improvement in child/parent relations and behaviour. This paper draws on material delivered to a parenting training course for practitioners in addition to participant observation of a parenting course. Interviews with parenting practitioners and parents, who were referred to the course or experienced parenting support, are also discussed. Whilst Elias’ theories of parenting are useful in relation to contemporary parenting policies, it is necessary to combine other sociological perspectives to demonstrate the tensions between parenting policies, local parenting interventions and the experiences of parents targeted by such policies. In particular, the findings show that due to classed and gendered experiences, parenting is situated in practice and due to the amount of pressure on parents to transform their parenting in a short amount of time, parents often struggled to implement informalised parenting practices due to their circumstances and the interventions they are subjected to.

Introduction

Poor parenting is continually cited in policy rhetoric as the underlying explanation of society’s problems (Nixon et al, 2006), where issues such as indiscipline, youth offending and truancy have all been apportioned to negligent parenting and where children’s behaviour reflects the lack of discipline and respect that should have been modelled by parents (Evans, 2012). From the introduction of Parenting Orders by the New Labour government in 1998 to the Conservative governments’ Troubled Families programme in 2012, we can see the consistency in rhetoric around parental responsibility which cuts across political party lines.

Norbert Elias (1998) noted that the biggest power-over relationship in society exists between parents and children. This is because children need to ‘become’ functional and law-abiding adults, which must primarily be modelled and overseen by their parents. Drawing on Elias’ theoretical framing surrounding the civilization of parenting, this paper will outline how the ‘discovery’ of children has led to child-adult relations being made more conscious, through informalised and relational parenting. Informalised parenting is where authoritarian, violent and harsh parenting is discouraged and the autonomy of children is encouraged. Relational parenting is where parents must think about the effects of their parenting style on the emotions of children.

The increased thoughtfulness of different parenting approaches reflect the anxieties surrounding childhood transitions into adulthood and have culminated in an intensification of ‘science’ and knowledge, best practice, monitoring of childhood development, and family interventions to try and guarantee correctly socialised adults (Dermott and Pomati, 2016). However, whilst informalised parenting from parent to child is championed, there has been a reformalisation of parenting between parents and the state. This is where parents can face sanctions for not implementing best practice parenting, including being referred to parenting classes or family interventions. Whilst Elias is useful in conceptualising ‘anxieties’ surrounding children’s socialisation and changing parenting relations, the reformalisation of parenting between parents and the state can be enhanced by synchronising a more rigorous class and gender lens to unpack what type of parents are deemed the most ‘risky’. This paper argues that guidance on parental practices are problematic when parenting in reality is situated – parents are having to deal with adverse circumstances that do not allow the space for idealistic parenting.

The structure of this paper is as follows: first, an outline of Elias’ thoughts surrounding the ‘growing up phase’ will be outlined. Second, Elias’ thoughts will then be cross referenced with developments of parenting practice in the parenting advice market and in policy. Third, data from a parenting training course for practitioners, a parenting course for families and family interventions will then be discussed and linked back to theory in order to demonstrate how the reformalisation of parenting is at odds with parents’ abilities to meet idealist parenting logics.

A theoretical construction of childhood and adult-child relations

It is important to outline Elias’ theories surrounding the construction of childhood and the relevance of this for contemporary debates surrounding perceived inadequate parenting. In earlier centuries, the process of socialisation, although still benchmarked against elitist codes of the time, was less conscious. However, from the industrialisation of society, parenting and the transition to adulthood has become much more cognisant (Elias, 1998). Changing family structures and women’s emancipation have also influenced theories of childhood, accompanied by more recent developments in children’s rights (Van Krieken, 2005). This context resulted in Elias (1998) suggesting that the problematisation of children grew due to the uncertainty of not being able to fully conceptualise the identities of children or how to train children, whereby there was the realisation; “children are not little adults, but only gradually become adult in the course of an individual social civilising process” (15). The increasing problematisation of children’s immaturity called for a need for best practice, intervention and risk management.

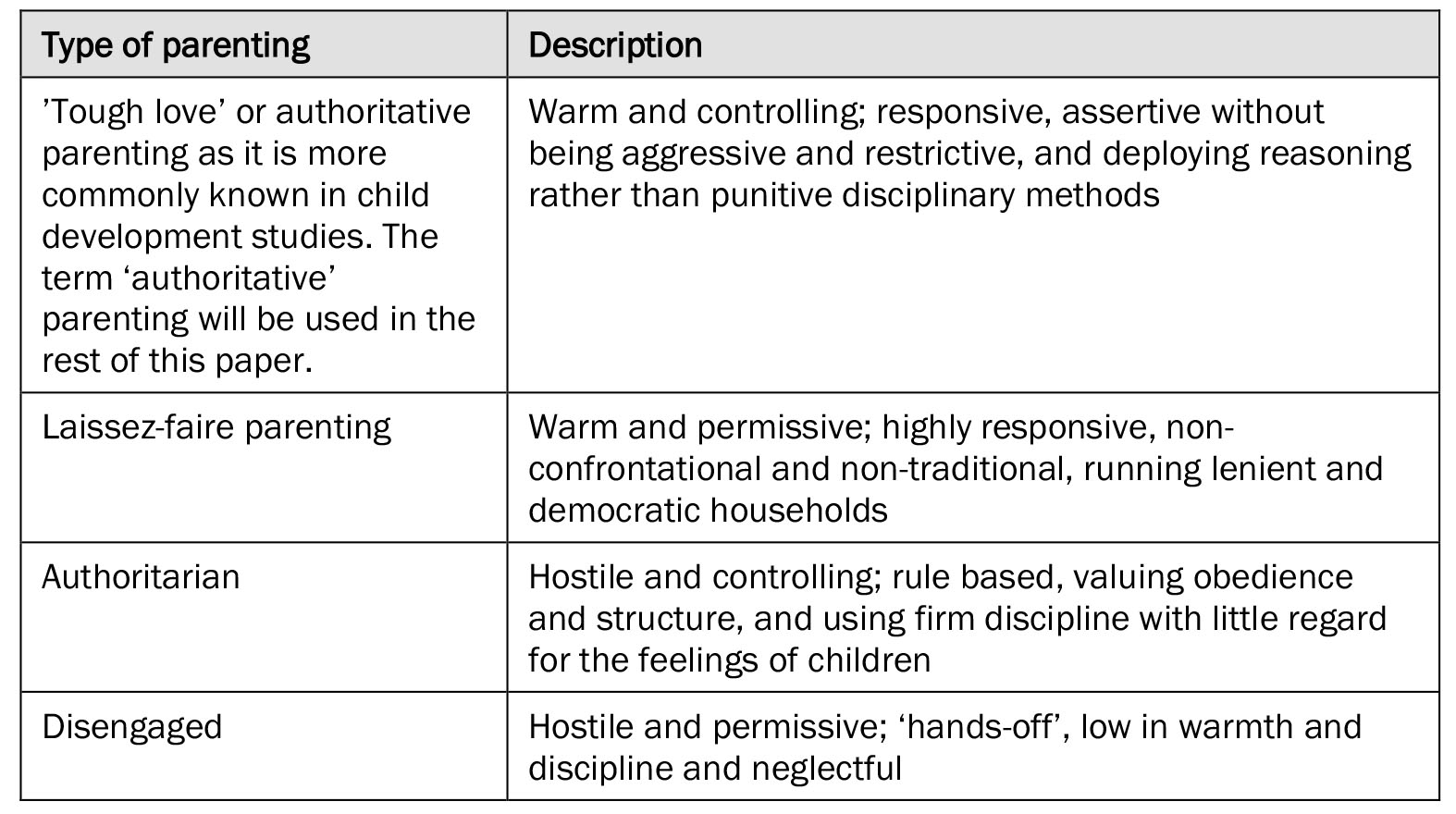

Thus there has been a proliferation of ideologies, theories and arguments in an attempt to reduce this unknown and guarantee the correct socialisation process. There has been a saturation of parenting pedagogy guides (manuals have existed since 1919, see Kitchens (2007)). This includes advice surrounding hygiene and metrics to monitor weight and nutrition, practical advice on discipline, bedtimes, diet and nutrition. However, as Elias alluded to, there has also been the development of a cultural focus on the moral socialisation of children that includes tips for improving child social learning and increasing child social and emotional development (Sanders, 2008). Key examples of this process over time have included children having their own privacy, autonomy and protection from violence (Elias, 1998). Ultimately, this has problematised child outcomes and the relations between children and parents. Parents now need to consider how their interactions, disciplining and parenting style will successfully shape their children into upstanding adults. A typology of parenting styles can be found below:

Elias (1998:20) stated that in pre-industrial society parents would have parented more “spontaneously”, based on “what they felt”, rather than empathy per se or based on how their actions/choices might affect children. This included using violence and engaging in behaviours such as substance (mis)use and sex in front of children which would be considered inappropriate today. This reflects more laissez-faire or disengaged parenting. However, in general, across pre-industrial, industrial and post-industrial society, the relationship between parents and children has been based on an authoritarian relationship where parents would make decisions and children would obey, to install discipline into children. In recent years complete authority/obedience has been disputed by experts as being not being effective, which can have negative emotional affects for the child including anxiety and low self-esteem (ibid: 16). The preferences and endorsements of different styles over time demonstrates Elias’ ‘informalisation’ of parenting, where authority is achieved by allowing children to be autonomous and disciplined through non-violent parenting. This has parallels with the definition of an authoritative parenting style, where there is much more concern considering the emotional wellbeing of children which encourages the (self-) regulation of the child through warmth over hostility.

Controlling child socialisation as a policy issue: the informalisation of parenting

The relevance of Elias’ theory has been pertinent to government policy since 1997. Children have been positioned as a ‘high stakes’ group that needs attention. New Labour governments have increasingly turned to science and evidence of ‘what works’ to ensure correct socialisation, parenting expertise based on ‘optimum’ child outcomes, and to manage potentially anti-social children (Lee et al., 2014; HM Treasury, 2003). The UK adopted the philosophy of ‘early intervention’, which meant that adverse childhood experiences and poor behavioural pathways in adulthood could be stopped if services intervened early enough.

Consequently, a range of health, criminal and social care institutions have evolved and joined up to control the process of childhood to adulthood in an idealised way. Under New Labour’s Child Poverty Strategy and Respect Action Plan, criminal and social policy co-joined to create a parenting ‘industry’ of Sure Start children’s centres, universal parenting support and targeted parenting education through family support packages (e.g., via health visiting, family intervention projects and/or government endorsed parenting programmes) (Powell, 2019; Respect Task Force, 2006). A multi-agency approach to families demonstrating actual and potential poor outcomes continued when the Troubled Families Programme which was rolled out in response to the 2011 riots. The programme was based on a key worker model, where a package of support could be developed around issues such as poor parenting, truancy, anti-social behaviour (ASB) and worklessness (Ball et al., 2016).

Across all governments there has been a commitment to support high quality evidence-based parenting based on the authoritative and informalised parenting style discussed earlier. The National Academy for Parenting Practitioners was created in 2007 to roll out training for the purpose of upskilling a range of practitioners in order to be able to give evidence-based parenting support to families (Asmussen et al., 2012). Alongside this, The Parenting Early Intervention Pathfinder (PEIP) allocated £7.6 million to 18 local authorities to roll out and test government endorsed parenting programmes, with the aim that every local authority will have implemented parenting programmes (Lindsay et al., 2011). The outcomes of the programmes were tested on reducing parenting laxness and over-reactivity, increasing parental wellbeing and improving child conduct and pro-social behaviours.

Consequently, parenting programmes became one of the most common methods of delivering parenting support to groups of parents (Nixon and Parr, 2009), as “a structured process of education and training intended to enhance the parenting skills of participants” (Bunting, 2004: 328). The aim of the programmes was to increase parenting efficacy to ensure parenting becomes ‘protective’ against social problems such as ASB. There are many models of parenting programmes available, concentrating on different child stages from 0-18 (Lindsay et al., 2011). The models are ‘integrative’ and are designed to work on skill, knowledge, attitude and mental health/wellbeing (Moran et al., 2004). Programmes are intended to upskill parents in terms of supervision, relationship building, anger management, setting behavioural standards and following through on warnings. With some variation, courses are planned around structured sessions over a number of weeks and can be delivered to groups in community settings and/or on a one-to-one basis within the home. Sessions are interactive, usually based on modelling, talk therapy, tip sharing and setting homework tasks (Moran et al., 2004).

There is now a large evidence base that suggests that parenting courses and support can have long term positive effects on parenting strategies and parental stress levels, and can reduce challenging behaviour exhibited by children (Bunting, 2004; Barlow and Stewart-Brown, 2001). Barlow and Stewart-Brown (2001: 126) found that changes articulated by parents included feelings of increased control, feeling less guilty, more empathy for their children and understanding of their behaviour. Parenting programmes could also decrease the use of harsh or physical discipline including physically and emotionally abusive behaviours such as smacking, criticism and name calling (Bunting, 2004) and ‘impulsive’ and/or ‘over-reactive’ parenting (Lindsay et al., 2011).

However, across the literature there is a sense that parenting advice is not guaranteed to be successful and depends largely upon the context of the family, who may have less educational capital or less access to resources. It is suggested that the high dropout rate and low attendance of parents on courses may be indicative of some parents finding it difficult to follow or adhere to the vast amount of material covered in programmes (Barlow and Stewart-Brown, 2001). Parents reported feeling judged by practitioners for behaviour (such as their child’s learning difficulties) which they felt they could not control (Holt, 2010). Some parents also felt that they already knew a lot of the information delivered.

It is clear that what Elias (1998) noted about the informalisation of parenting is present in the design of parenting programmes, which reflect the descriptions of authoritarian parenting e.g. using constant high praise and warmth strategies and avoiding low criticism and permissive strategies. Parenting is to be relational – i.e. listening, communicating and negotiating, rather than authority ‘over’ – including using violence. Instead desirable behaviours will be reinforced, rewarded and encouraged. However, whilst Elias suggests these social relations are unplanned, it appears that since 1997 there has been an emphasis on ensuring the socialisation process in children happens properly – with a belief that family support will be successful in every family, despite some families facing adverse circumstances. The next section of this paper will outline how parenting has become ‘reformalised’, which has consequences for families facing social stress or from a different class culture.

Reformalisation of parenting

This paper has argued so far that the relations between children and parents have changed through informalisation, but attention needs to be given to how the relations between the state and parents have also evolved. Parenting policy brings with it a shift from an understanding of care as something which takes place inside the private space of the family to a ‘public health’ issue dealt with by the state (Dermott and Pomati, 2016). Rhetoric would suggest that the family cannot be trusted to care for children properly, and corporate state parenting via education, social care and child protection is more efficient at ensuring the socialisation process (Bristow, 2013). This demonstrates a ‘reformalisation’ of parenting, in terms of the state-parent relationship as descriptions of bad parenting have cemented the examination of parenting as a legitimate means of scrutiny of families, where parents can be monitored, sanctioned and penalised via professionals such as health visitors and key workers or through formal Parenting Orders and Parenting Contracts (Gillies, 2008).

Whilst Elias has been useful in helping reflect on the unplanned informalisation of parenting over time, his theories need to be enhanced by overlying a more prominent class and gender based analysis, where interventions to mitigate against poor parenting were planned based on middle-class moral values. To disentangle this, it is important to appraise the following quote:

“Such a modified authority relation, however, now really demands of parents, as we can see, a relatively high degree of self-control, which as a model and a means of education then rebounds to impose a high degree of self-constraint on children in their turn” (Elias, 1998;37-38)

What is implicit within this quote is that parenting branches out beyond the pragmatics of parenting into constructed good parenting ‘role models’. Despite parenting policy being sold as ‘universal’ support, a systematic pattern over time is that these policies are, in reality, targeted at high risk and single (female headed) families who live in deprived areas, in order to intervene in the families predicated on having undesirable outcomes or cultures. Even though there is a lack of robust evidence that deficient parenting and poverty are linked, throughout many of the early intervention publications, underclass symbolism is reflected throughout (Dermott and Pomati, 2016). The blame lies with chaotic families that fail to break the cycle of poor parenting, as they do not critically reflect on their upbringing or take appropriate steps to ensure they parent differently, and set good examples, for example through employment, rather than relying on the welfare state (Allen, 2011: 41).

Furthermore, in 2015, the Building Great Britons report was released, which argued that the foundations of a good citizen needed to be achieved in the first 1001 days of a new-born’s life (APPG, 2015). This philosophy re-cites and criticises the effects of parental worklessness, parental conflict and maternal mental health on children’s futures. By 2016, there was renewed emphasis on tackling these three concerns. Perinatal mental health was receiving funding due to the impact poor maternal mental health could have on children’s development, which had been lobbied for by both the Field and Allen reports (Allen, 2011; Field, 2010). In 2017, the report ‘Improving lives: helping workless families’ was released which reiterated how worklessness can negatively affect the pathways that children could take and income support would require ongoing conditionality (DWP, 2017). In addition to the concerns surrounding worklessness, parental conflict has also been a target of government intervention where family therapy programmes are needed to remedy the conflict children may be adversely affected by.

Effectively, the need for parents to be ‘a model and a means of education’ places a tax on parents to provide children with intensive attention (Elias, 1998: 38). This includes constant positivity, stability, continuous positive experiences and extracurricular activities (Churchill, 2007; Lee et al., 2014). This often ignores a situated and sociological lens, and becomes a challenging experience for parents who do not necessarily have the economic or social capital to engage with idealised values of parenting – but are goaded to build ‘resilience’ against adverse structural factors like austerity. Or as Field’s (2010: 16-17) report states, having ‘parental aspiration’ and a good ‘attitude’ can “trump class background and parental income.”

Finally, a concentration on mothers’ qualifications/work experience and mental stability has ramped up feminised scrutiny and gender amoralism in relation to the reworked sexual contract of employment-intensive mothering (Jenson, 2018). This is where the assumption women can provide specific levels of wealth and warmth without any opportunity costs, has not been sociologically reflected on in policy logics. The policy concern surrounding maternal mental health is deemed a risk factor in terms of child development, which may affect the ability for mothers to build ‘warm’ attachments and empathy for and in children. Jensen (2018) has argued this shows the ‘emotional capitalism’ of adverse circumstances – where families, and particularly women, facing disadvantage must nevertheless better themselves, their children’s life chances, despite lack of resources and opportunities, social stress and illness.

Methodology

This section of the paper will outline the methodological approach the research took. The overarching research aim was to understand the ethical, normative and policy implications of intensive family-based support. The research was based on the author’s PhD research attached to the ‘Welfare Conditionality: Support, Sanctions and Behaviour change’ project funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. The research received ethical approval from the University of Sheffield. The length of study took place from 2013-2017.

The methodology was guided by the gaps in clarity surrounding the complexities and nuances of behaviour change that occur in families over time. The research used a case study approach to understand the mix of interventions delivered to families who were deemed problematic and referred to intervention – but in a context that situates behaviours, complexities, interactions, social processes and opinions. The location of the case study was picked on the basis that there was a working Troubled Families Programme in the local authority.

As recommended by Yin’s (1994) three principles of data collection, data was collected from: 1) multiple sources of evidence; 2) inputted into a case study database; and 3) maintaining a chain of evidence by using a conceptual framework. Data collection included two approaches to enable methodological triangulation; participant observation as well as interviews with practitioners and service users. Yin’s first principle can be demonstrated in the table below:

I attended a nationally available parenting course, run by two parenting practitioners, aimed at children under ten years old. I attended 13 out of the 14 weeks. Eleven parents began the parenting course with an attrition rate through the weeks of about 30-40 per cent due to two parents having a clash with commitments elsewhere, one parent having a child removed from their care and one parent deciding that she no longer wanted to attend. Attendance fluctuated, but seven out of the 11 parents consistently attended. Nine of the parents were women and two of the parents were men, who attended with their female partners. The course took place in a working class area within the case study location. The parents had all been referred to the programme via key workers, a school, a children’s centre or by other practitioners in touch with the families due to concerns around children’s defiance or children’s behaviour.

I observed a two-day training course where practitioners were trained in the parenting practices to be modelled to parents. The format and content of the training were similar to how the parenting course was delivered but were condensed into a shorter time period.

I was immersed in the parenting and training courses and would contribute to discussions with the parents and practitioners. Field notes from the course and training content were made, including parenting techniques, course materials and tips and parents’ and practitioners’ reactions to the course material. In relation to the parenting course, I was initially concerned that the parents might view me as an intruder as I am not a parent and would not necessarily be able to contribute any knowledge to the group. However, the parents appeared to accept me as a student, as they too were attending the course to learn. I have no background in parenting practice.

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken to explore and conceptualise what interventions were delivered to each family. A longitudinal element was used with ten families referred for family interventions under the Troubled Families Programme in order to track any behaviour change in families overtime. These interviews were mainly face-to-face apart from one family who requested their interviews to be over the telephone. Face to face interviews were undertaken with parents attending the parenting course. A range of practitioners employed in service provision in the public, private and third sector (many of whom were family key workers) were also interviewed in order to triangulate service provision and impact.

The researcher was mindful that the collection of fieldnotes could become ‘biased story telling’ (Yin, 1994). The fieldnotes recorded were turned into field ‘records’ and used to develop and inform wider themes in conjunction with the interview material and access to the training presentations. The data was also used to inform future interviews. This created a ‘database’ as recommended by Yin’s second principle.

Principle 3 of Yin’s recommendations is ‘maintaining a chain of evidence by using a conceptual framework’. One of the approaches to analyse intervention impact was to draw on Blamey and Mackenzie’s (2007) approach to conceptualising behaviour change and draw on theories of Realistic Evaluation. First, a thorough breakdown of the intervention design, processes, goals and targeted groups needed to be understood in order to contextualise behaviour change (Ibid, p. 446). Second, framing interacting ‘context, mechanisms and outcome configurations’ (CMO) of the individual/family alongside the structure of interventions allows a consideration of the ‘motivational’, ‘situational’ and ‘causal’ explanations of behaviour change (Ibid, p. 446). By mapping CMO it is possible to discern which aspects of the programme had the ‘desired effect’ on behaviour change, in order to identify the personal and programmatic barriers to, and triggers for change (Ibid, p. 450).

Delivery of informalised parenting knowledge and best practice

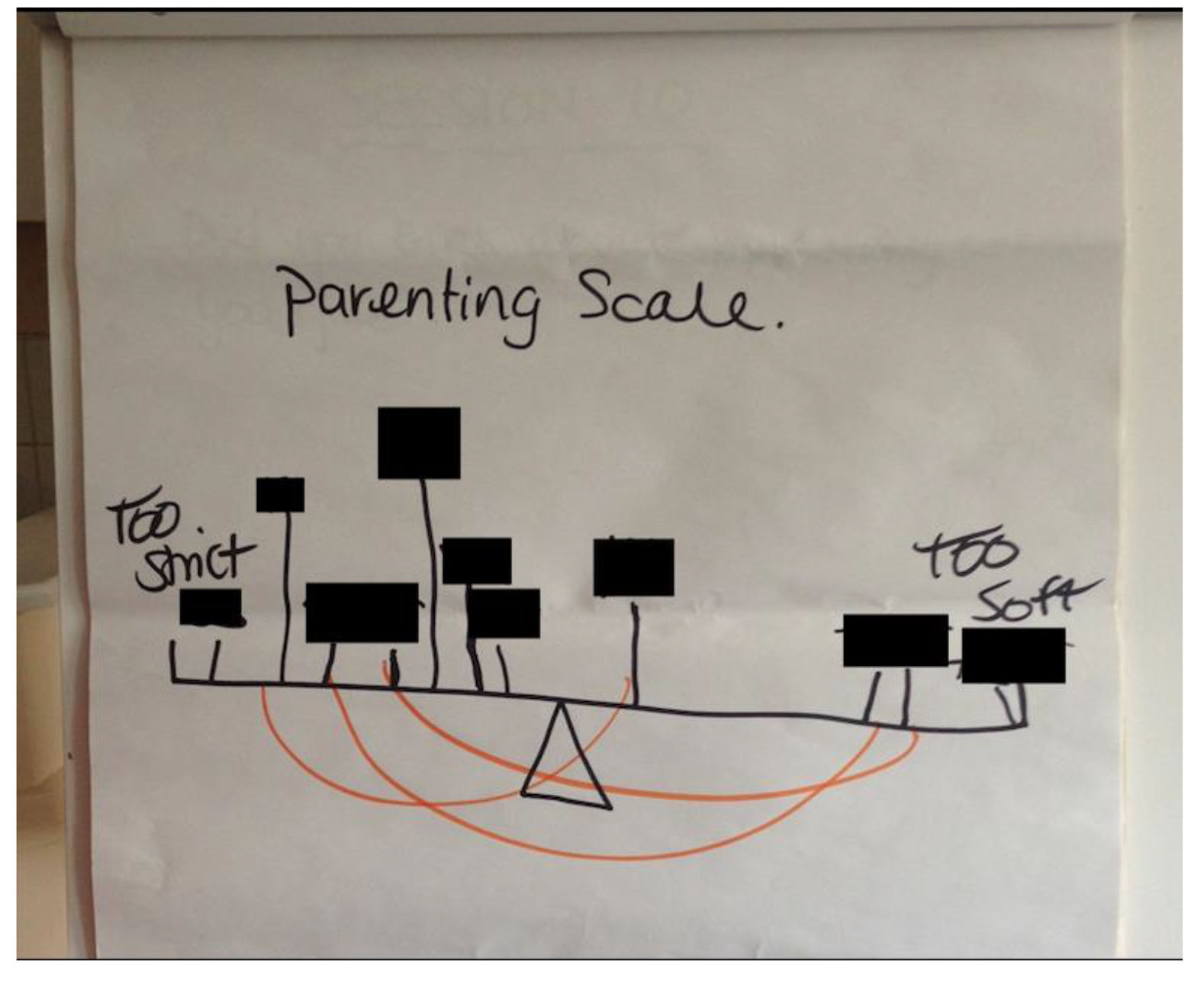

This section of the paper will analyse the case study data. Using a ‘parenting scale’ diagram (figure 1), the practitioners asked parents to mark on the scale whether they believed the way they were parenting was too harsh or too soft. Parents were asked to reflect on whether they are too authoritarian or give their children too much/not enough ‘autonomy’. The practitioners encouraged a ‘firm but fair’ approach which parents could achieve by setting clear and realistic limits that children had to adhere to, which would encourage boundaries, safety, manners, respect and good behaviour. This is line with the ‘authoritative approach which has been idealised in the parenting and policy literature.

Parents were told that certain parenting styles such as authoritarian parenting, which included negativity, over-use of criticism, threatening the child, shouting and too many rules would have an adverse effect on children listening to adults, their behaviour and their self-esteem – which could affect their ‘future’:

“The stakes are really high, you can either carry on treating and being like you are, being negative to your kids, using negative language towards your kids, shouting, and see what happens – kids misbehaving. Your kids will grow up, and that will be their life…if they grow up to be unconfident, always getting nagged, low self-esteem, they miss loads of opportunities” (Parenting practitioner 1)

This quote reinforces the drive for informalised and positive parenting. The message was that parents are forgetting to praise children and parents are often wrongly using parenting strategies that quickly escalate into punishing the child. In fact, parents would discipline their children via shouting and/or smacking. The practitioners wanted to teach self-restraint not only to children, but to parents too, so that there was less violence towards children. Self-restraint was learnt on the course by encouraging listening and compromise. The practitioners also introduced the ‘ignoring’ strategy and the use of logical consequences to help children self-regulate their behaviour and understand the consequences of what they had done wrong. The group discussed behaviours parents could ignore, such as swearing, tantrums, mimicking and whinging. When parents were faced with these situations, the practitioners advised that parents made no eye contact with the child and moved away, as engaging with a child that is misbehaving can make the situation worse. Parents were advised to follow through with ignoring the child, even if it is in a public place. The success the ignoring technique had on self-restraint was clear, as shown by the parent below:

“I woke up, these woke up at six, and I went back to sleep for a bit like I always do, and they will play in their bedroom but I walked up and they had ripped the wallpaper off the walls…but before that…I would have gone on one and slapped them…from the course I have learnt to be a lot calmer” (Parent of 2)

This had stopped the parent losing their temper and striking their child. The parent reported increased feelings of control, confidence and wellbeing – feelings that many parents on the course had. When behaviours could not be ignored, harsher punishment needed to be used, such as ‘timeout’. Parents were taught that ‘timeout’ should be a spot which removes the child away from fun, to somewhere that is boring, for a fixed length of time. Then there should be a consequence for the child (e.g., they cannot play computer games that evening). After using the ignoring technique, logical consequences or timeout, practitioners stressed that parents should get back into praising as soon as bad behaviour stops, even if parents are still annoyed at the child. Self-control could also be taught to the child through sticker charts, incentives, rewards and allowing children to be involved in rule-making e.g. bedtimes.

The practitioners wanted parents to ‘catch children being good’ and to reward good behaviour. This needed to be effective praise; and not critical praise such as ‘well done for making your bed, why can’t you do it every day?’ A poem which outlined that children who had been praised felt more fulfilled and encouraged than children that had been criticised was given to parents. The mantra of the course was that it takes 17 positives to combat 1 negative comment.

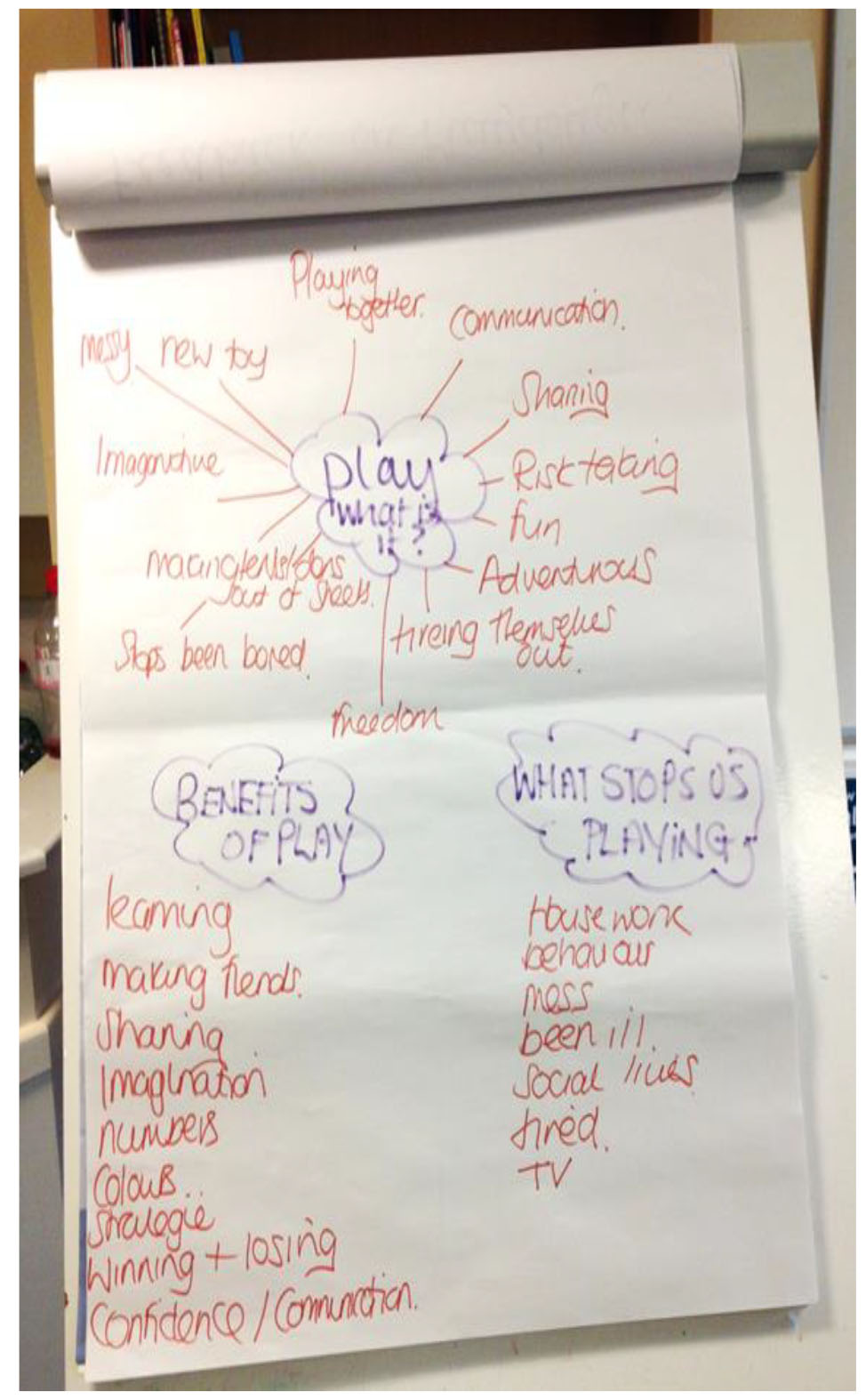

The positive parenting approach, alongside the use of praise and less violence, also combined play where parents were expected to engage in at least ten minutes of child-led play per day. There were different forms of play that were discussed and encouraged within the parenting course and in the interventions, for example physical play (going to the park); quiet play (singing, story time); tactile play (painting, games) and imaginative play (dens, dressing up). Practitioners at the training course were also advised they should also ensure that parents are letting the child control the play, and that the parents are not rushing the child or imposing their own ideas. This would help build attachment and encourage pro-social behaviours in the child such as confidence, creativity, sharing and problem-solving that are conducive to being ‘adult ready’ (Field, 2010).

The findings from the research demonstrate Elias’ theory that retracting the hierarchy between parent and child and strict codes of discipline has created an informalisation of parenting practices based on reducing physical and psychological/emotional violence (although there is still discipline), promoting independence of the child and using encouragement and play to create high warmth. Elias argues:

“We find ourselves in a transition period, in which older, strictly authoritarian, and newer, more egalitarian parent-child relations exist alongside each other, and which often coexist in one and the same family” (1998:16).

However, there was some resistance to this shift in the relationship by parents as parenting practitioners found that parents were concerned that children having more ownership of decision making would make the child demanding, and increased praise would spoil the child and make them arrogant. Positive parenting was a different method of parenting, which made parents suspicious as traditionally it might be argued that the socialisation process is associated with discipline and rules:

“I have [heard] that quite a bit, you know where people think kids have too much choice and too much voice now, and ‘when I was younger we didn’t dare speak and look at our parents.’ If they have been brought up like that they can’t see [the benefits of positive parenting], they call it new-age stuff” (Parenting Practitioner #2)

In fact most of the parents attended the parenting course initially to find out how to discipline children rather than to praise them:

“A lot of parents want to learn, but they want to learn about the naughty step or whatever, they watch Supernanny and things and they want to learn that” (Parenting Practitioner #1)

Interestingly, Gillies (2008) discusses how working-class women tend to be more disciplinary than their middle-class counterparts and wouldn’t focus on making their children feel ‘special’ as classed trajectories disallow the ‘cultivation’ of working-class children – despite the parenting practitioners dismissing this determinism. Furthermore, many parents attending the parenting course were referred because they are failing to discipline their children. Telling parents not to use discipline per se, but praise, is something that appeared to be at odds with the threats that some parents were being faced with (such as social care monitoring and involvement). This appeared to be a problematic irony in parenting policy which parents had to untangle. It also poses the question that if parenting takes a high praise and high warmth approach, which has more successful results than low warmth and discipline, why does the state also believe that sanctioning parents will be more effective over supportive measures.

The operationalisation of informalised parenting

The investment in policing the parenting deficit, despite the fact parents spend copious amounts of time with their children, means the ‘work’ of parenting has taken off due to constructions of ordinary family conflict being constructed as symbolic of a moral panic (Jenson, 2018). The internalisation of these discourses had resonated amongst parents who felt fear and shame for not being able to control their children through their lack of authority, or feeling they are not a ‘naturally’ good parent. The parenting course aimed to rationalise these fears and argued that parenting was not something that should be thought of as natural but could be taught as a ‘bag of tools’ – or through scientific knowledge and evidence-based practice.

However, whilst the pragmatics of bedtimes etc were taught, what is fundamental to note is the operationalisation of teaching informalised parenting was actually through getting parents to be reflective. Being ‘reflective’ to increase parenting ability, was a key part of the course which could craft parenthood (Edwards, 2012). Whilst it has already been noted that parents needed to reflect on their parenting style through the parenting scale (figure 1), parents were also asked to watch clips of child-parent relations (e.g., challenging situations such as tantrums in a public place) and think about ‘what could they have done instead?’ This was a tool to get parents to reflect on their own parenting (mistakes) via watching another parent ‘fail’ and eventually relating it back to their own practices, rather than being told out right their parenting was inadequate:

“They can actually see themselves, and it is not directed straight at them, so they can take that information – that light bulb moment and think ‘crikey, I do that as well’” (Parenting practitioner 1)

Homework sheets, checklists and a weekly phone call by the parenting practitioners were used to operationalise these reflections and ensure appropriate action was put into practice. Practitioners on the parenting training course were asked to challenge parents if they were not self-reflecting on how damaging their parenting could be. Practitioners were encouraged to highlight to parents that if “they don’t change, then nothing will.” They were also advised to say to parents “so are you happy for everything to stay the same?” – especially if parents had given up on implementing parenting techniques.

The effect of informalisation and reformalisation on parents

The mechanisms previously mentioned feed into ideas of the emotional regime where parents need to work out happy mediums between being less authoritarian (but still authoritative), not giving children low warmth or negative experiences, and ensuring attachment. The set-up of the parenting course could be argued to be complicit and uncritical of ‘making class’ in terms of morals, choices and values, forgotten under the idea of what constitutes an ‘effective’ middle-class family narrative:

“It asks them to step out of their social and political worlds, turn their gaze onwards and ask: what kind of parent are you? What kind of parent do you want to be?” (Elias,1998: 96)

From a class-based perspective, the positive and play approach to parenting, perhaps whilst presented as helpful parenting strategies, could be argued to reflect reformalisation via decontextualised patriarchal and classed frameworks of power which fixes experiences. Jensen (2018: 110) is able to explain this assertion by arguing “the ‘warmth’ of parenting style, which promises to free children of any social or economic disadvantage” is problematic, as it draws on ideas of ‘emotional capitalism’, where despite structural barriers (which are presented as reductionist), parents (especially women) must individually manage and even overcome the challenges they face in order to conjure a positive childhood experience despite having limited resources. These ideas can be shown by figure 2, where parents on the parenting course were asked to list what stops play, in order to make parents realise they would need to overcome barriers to play. These included being ill and balancing their social lives in order to enrich their children’s experiences. The cost-benefit analysis of not playing was used to show that despite barriers, playing with children can develop the pro-social behaviours in children that society wants to see (including risk taking behaviours and confidence), which are inherently classed.

Despite parenting being represented as predominantly behavioural, rather than structural, the parenting practitioners considered the impacts of poverty that could affect the success of parenting interventions:

“The truth is they do seem to leave right, you are all armed aren’t you and tooled up and I feel confident now, they have given me all the things I need to do this week, and then boom life slaps you right in the face cos actually, your debts are still there, I still live in this crappy house, I still have got him texting me vile things and the kids are winding me up, school has just talked to me about something I didn’t want them to tell me about, all your positivity, cos you only get it once a week, starts to drain out of you and before you know it you are back to square one, they often say I was alright until Wednesday, say you do a group on Monday, everything was going well, until Wednesday…it almost seems that they have two or three days of motivation and then it goes” (Parenting practitioner 1)

Despite the practitioners recognising the injuries of class, and being from working class backgrounds themselves – alongside the fact that parents engaged with support for their children’s behaviour, parents still needed to do better and take on middle class parenting practices to enrich working class practices to more desirable standards (Nunn and Tepe-Belfrage, 2017). Decontextualizing parental circumstances and performing middle class norms is a fixed solution, which symbolically denies anything other than middle class benchmarks of security, stability, positivity and enrichment.

These arguments are relatable with Elias’ thoughts on the child socialisation process which could be controlled by knowledge and expertise, where families can “be educated out of their failing lifestyle” (Taylor and Rogaly, 2007: 440). Jensen (2018) calls this the ‘psychologising of parenting’ where all (structural) problems can be solved by drawing on expert advice or being ‘conscious’ of their interactions with their children. However, parenting as a ‘psychology’ means that good parenting denies negative feelings, creates pressures for parents and denies any alternative experiences felt by parents – for example, depression. As Elias (1998: 21) noted:

“But today a legend has become established that makes it look as if parental love and affection for their children is something more or less natural and, beyond that, an always stable, permanent and lifelong feeling.”

This sentiment around the assumption of continuous high warmth parenting was institutionalised as an expectation by the parenting practitioners. They argued that parents tended to use a lot of negative criticism, which they saw as an issue related to depression and mental illness, which, like much policy discourse is conflated with attitude and motivation. For example when the researcher asked the two parenting practitioners how depression impacts on parenting the response was:

“Parenting practitioner 1: Motivation int it, you can’t find it in your heart to be happy…your kids see you looking very sad…you tend to be more argumentative if you are depressed aren’t you

Parenting practitioner 2: You don’t want to go out the house…a lot of parents, you walk in on a beautiful day like this, and curtains are closed, it is in the dark

Parenting practitioner 1: You sleep a lot when you are depressed

Parenting practitioner 2: It is a bit of a cycle int it and they haven’t got the motivation to play or do anything

Parenting practitioner 1: My experience of parents that I have worked with who suffer from depression is you are more likely to give in, because anything for a quiet life, so you are not going to stick to your rules, you are not going to stick to your boundaries, you are going to be pretty inconsistent. I think cos you are going to have good days and bad days so you are being quite inconsistent and it is being consistent that gives the kids the wobbles”

Many of the parents who had depression, were described as ‘absent’ parents by practitioners and this can become a child protection concern as parents may not be supervising their children adequately. As Jensen (2018: 86) notes, poor maternal health is a problem because it can mean “failure to provide adequate emotional care, to regulate their own feelings or to generate emotional resilience and skills in their children”. This penalises mothers for not being able to manage their own mental health and enrich their children’s lives, with the assumption that parents can cast aside mental health problems. Parents/women who had mental health problems were a particular concern for practitioners in terms of the child, rather than the mother herself. For example, the Health Visitor noted:

“I would be looking out for as a health visitor when someone was pregnant or had just had a baby would be that the child is the focus you can’t lose sight of the focus, and sometimes for lots of mums there might be mental health problems low mood depression or substance misuse and they become very absorbed in themselves and if you see that happening, they’re not putting the child first that’s when my level of concern would be raised because then the mothers, fathers or parents behaviour would be having an impact on the child, so then it is very important that we intervene as that child is then becoming or is vulnerable. They’re not going to achieve their outcomes because the parent is not putting the child’s needs first or before their own and it would become quite urgent that we intervene” (Health Visitor)

The impetus on ideological mothering has disallowed space for resentment of children or being unhappy as a parent. However, parenting today has shifted onto the needs of the child, at the expense of parent(s) needs, and condemns parental low moods as selfish and risking the neglect of children. Ideological mothering also bleeds into women’s role in employment, which draws on political discourses of ‘warmth over wealth’, but also the need for mothers to be employed to be seen as a good role model. This creates impossible tensions for women. However, the motherhood double jeopardy was still blamed on women themselves:

“She wants a future for herself, she wants a job…I think her kids get in the way of all that, I think there is a lot of resentment there with her kids, she is young, she didn’t intend to be a single parent but she is, I think there is a bit of resentment there I don’t think she has got a very, to me doesn’t seem to have a very strong bond with those kids” (Parenting practitioner 1)

This is perhaps reflective of how sexual politics is still as relevant as ever, despite popular post-feminist connotations of ‘choice’ (Jensen, 2018). Despite ambition, or scenarios where women have to work, parenting remains gendered and moralised where on one hand women are expected to work and be good role models, but on the other should also sacrifice their careers and dedicate themselves to intensively parenting their child. This reflects gender and class ‘amoralism’, that is still a present issue which fails to recognise that, for working class women, their ‘choices’ and opportunities remain heavily constrained and scrutinised.

Conclusion

Elias argued that the long term process of parenting and adult/child relations has moved towards an informalisation of parenting, where there appears to be less violence and authoritarian parenting towards children, as well as more autonomy given to the child. However, due to perceptions of anti-social and undisciplined generations of children, parenting policy apparatus based on middle-class values has been rolled out due to state mistrust in parents to care for and discipline children properly (Bristow, 2013). Those parents tend to be (single) mothers from a working class background. Policy strategies such as parenting courses and family interventions are a medium through which proper socialisation could take place and parenting can be monitored and criminalized if deemed inadequate. The techniques taught during the practitioner parenting training and during the parenting course were in line with informalised parenting and instead of using ‘low warmth’ and ‘high criticism’ techniques, play and praise were championed. Even though parents were often under the threat of sanctioning, families had to negotiate this threat and manage the informalisation of parent/child relations through positive parenting. This sent a message that working on the characters of children can overcome the adverse situations parents find themselves in, which denied the situated classed experiences and lack of resources parents were faced with.

Emily Ball, School of Social Policy, Department of Social Policy, Sociology and Criminology, University of Birmingham. Email: e.ball@bham.ac.uk

Allen, G. (2011) Early intervention: the next steps, an independent report to Her Majesty’s government by Graham Allen MP. The Stationery Office.

All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Conception to Age 2: The first 1001 Days (2015) Building Great Britons.

Asmussen, K.A., Matthews, T., Weizel, K., Bebiroglu, N. and Scott, S. (2012) Evaluation of the National Academy of Parenting Practitioners’ Training Offer in evidence based parenting programmes. London: Department for Education.

Ball, E., Batty, E. and Flint, J. (2016) Intensive Family Intervention and the Problem Figuration of ‘Troubled Families’. Social Policy and Society, 15, 2, 263-274. CrossRef link

Barlow, J. and Stewart-Brown, S. (2001) Understanding parenting programmes: parents’ views. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 2, 2, 117-130. CrossRef link

Blamey, A. and Mackenzie, M. (2007) Theories of change and realistic evaluation: peas in a pod or apples and oranges? Evaluation, 13, 4, 439-455. CrossRef link

Bristow, J. (2013) Reporting the riots: Parenting culture and the problem of authority in media analysis of August 2011. Sociological Research Online, 18, 4, 1-11. CrossRef link

Bunting, L. (2004) Parenting programmes: The best available evidence. Child Care in Practice, 10, 4, 327-343. CrossRef link

Churchill, H. (2007) New labour versus lone mothers’ discourses of parental responsibility and children’s needs. Critical Policy Analysis, 1, 2, 170-183. CrossRef link

Dermott, E. and Pomati, M., 2016. ‘Good’ parenting practices: How important are poverty, education and time pressure? Sociology, 50, 1, 125-142. CrossRef link

DWP (2017) Improving lives: Helping Workless Families. London: Department for Work and Pensions.

Elias, N. (1998) The civilizing of parents. In: J. Goudsblom and S. Mennell (eds) The Norbert Elias Reader. New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell: 189-211.

Evans, R. (2012) Parenting orders: The parents attend yet the kids still offend. Youth Justice, 12, 2, 118-133. CrossRef link

Field, F. (2010) The Foundation Years: preventing poor children becoming poor adults, The report of the Independent Review on Poverty and Life Chances. The Stationery Office.

Gillies, V. (2008) Perspectives on parenting responsibility: contextualizing values and practices. Journal of Law and Society, 35, 1, 95-112. CrossRef link

HM Treasury (2003) Every Child Matters. London: HM Treasury.

Holt, A. (2010) Managing ‘spoiled identities’: parents’ experiences of compulsory parenting support programmes. Children & Society, 24, 5, 413-423. CrossRef link

Jensen, T. (2018) Parenting the crisis: The cultural politics of parent-blame. Policy Press. CrossRef link

Kitchens, R. (2007) The informalization of the parent-child relationship: An investigation of parenting discourses produced in Australia in the Inter-War years. Journal of Family History, 32, 4, 459-478. CrossRef link

Lee, E., Bristow, J., Faircloth, C. and Macvarish, J. (2014) Parenting culture studies. Springer. CrossRef link

Lexmond, J., and Reeves, R. (2009) Building Character. London: Demos.

Lindsay, G., Strand, S., Cullen, M.A., Cullen, S., Band, S., Davis, H., Conlon, G., Barlow, J. and Evans, R. (2011) Parenting Early Intervention Programme Evaluation (Research report DFE-RR121 (a)).

Moran, P., Ghate, D., Van Der Merwe, A. and Policy research bureau (2004) What works in parenting support?: a review of the international evidence. London: Department for Education and Skills: 49-99.

Nixon, J. and Parr, S. (2009) Family intervention projects and the efficacy of parenting interventions. In: M, Blyth and E, Soloman (Ed.) Prevention and Youth Crime: Is early intervention working? Bristol: The Policy Press: 41-52. CrossRef link

Nixon, J., Parr, S., Hunter, C., Myers, S., Sanderson, D. and Whittle, S. (2006) Anti-social Behaviour Intensive Family Support Projects: An evaluation of six pioneering projects. London: Communities and Local Government.

Nunn, A. and Tepe-Belfrage, D. (2017) Disciplinary social policy and the failing promise of the new middle classes: the troubled families programme. Social Policy and Society, 16, 1, 119-129. CrossRef link

Powell, T. (2019) Early Intervention (Briefing Paper Number 7647). London: House of Commons Library.

Respect Task Force (2006) Respect Action Plan. London: Respect Task Force.

Sanders, M.R. (2008) Triple P-Positive Parenting Program as a public health approach to strengthening parenting. Journal of family psychology, 22, 4, 506. CrossRef link

Taylor, B. and Rogaly, B. (2007) ‘Mrs Fairly is a Dirty, Lazy Type’: Unsatisfactory Households and the Problem of Problem Families in Norwich 1942–1963. Twentieth Century British History, 18, 4, 429-452. CrossRef link

Van Krieken, R. (2005) The ‘best interests of the child’ and parental separation: On the ‘civilizing of parents’. The Modern Law Review, 68, 1, 25-48. CrossRef link

Yin, R.K. (1994) Case study research: Design and methods. London: Sage.