Abstract

The analysis presented in this article is dedicated to the observation of political initiatives to safeguard intangible cultural heritage (ICH), with a special focus on asymmetries in governance and potential long-term resolutions carried out at national and local levels. The case study presented reveals the evolution of the political, institutional and legislative mechanisms implemented by the Cape Verdean state since its entry into the ICH global conservation system. Furthermore, the gaps, outcomes and opportunities configured in this specific context are addressed as a contribution to the reflection upon diverse models of governance. The study, based on critical heritage studies and anthropology, is built on data collected through a mixture of methodologies such as participant observation, interviews and archival analysis. Data collection took place during an ethnographic fieldwork visit to the archipelago as part of a six-month internship at the National Heritage Institute. The contribution of the analysis, besides the observation of a specific case, lies in the consideration of the ICH political category as a long-term project. It also considers the asymmetries between the stakeholders and scales involved in such heritagization processes as a topic which is central to its success.

Introduction

Over recent decades, there has been a radical reframing of the concept of cultural heritage that has consequently affected political, institutional, social and academic perspectives. Even though there is a tendency to believe that cultural heritage policies and systems have always existed, they are in fact modern institutions that reflect the need to create linear and articulated historical timelines to underpin the distinctiveness of both particular social groups and nation states (Graham et al., 2005; Hafstein, 2018). However, there are many scales and stimuli behind contemporary heritagization processes and the rapid – and continuous – adaptation of policies and projects related to them is a complex system that encompasses a variety of factors such as the living and dynamic constitution of intangible cultural assets; the multiplicity of stakeholders and scales involved in such processes; and the unpredictability of the frictions between them.

Although the centrality of international institutions and guidelines that regulate the global governance of cultural heritage are recognized here, the constant “creative frictions” (Bortolotto, 2016) that emerge from national and local initiatives are observed as an important element for the success of governance practices and a key focus for the construction of a critical framing of the category of intangible cultural heritage (ICH). Therefore, this article is centred on a case study of the political dynamics and governance of heritagization processes in the archipelago of Cape Verde. This is based upon six months of ethnographic work carried out as part of the author’s doctoral research, and based on diverse methodologies, such as participant observation, interviews and archival research. This involved monitoring of the institutional and legislative evolution of Cape Verdean heritage policies, participant observation of the activities of the National Heritage Institute of Cape Verde (IPC-CV) and discussions with communities participating in different safeguarding projects. Together these allowed different perspectives and scales to be examined, as well as particular governance issues and resolutions to be identified.

As well as displaying key attributes that underpin ICH such as contemporary oral narrative practices, oral traditions and heritage initiatives, the Cape Verde archipelago was chosen as the research field was oriented principally by its prominence in the global ICH safeguarding system. This option was taken despite characteristics such as its relative geographical isolation, the scarcity of resources and the relatively recent history of its national institutions, since the archipelago only achieved independence from Portuguese colonial rule and exploitation in 1975. Found uninhabited at different times in the 15th century, the islands have gone through different cycles of settlement and exploration. Santiago Island, where the capital Praia is located, was the first to be populated with the aim of guaranteeing Portuguese dominion over the islands, which were of great importance for maritime explorations and the trading of enslaved people across the Atlantic. The archipelago, located off the coast of West Africa, comprises ten volcanic islands and has an arid climate characterized by constant droughts and low rainfall levels, which have given rise to cyclical famines throughout its history. These geographical conditions are also associated with a lack of natural resources that, apart from the strategic importance of its ports, made Cape Verde one of the least lucrative Portuguese colonies.

From the forced interaction between the Portuguese and enslaved colonists from different parts of the African continent, diverse sui generis cultural practices have emerged, including the Cape Verdean language. In common with other colonies these were repeatedly denigrated and rebuked up to the end of colonial domination in 1975. The struggle for independence, led by political party PAIGC, was marked by pan-Africanist ideals and the initial binational liberational project with Guinea Bissau. This brought the archipelago politically and culturally closer to the African continent, a position that subsequently was to be slowly abandoned, especially from the 1990s on. Cape Verde’s positioning and discursive practices regarding historical, cultural and political alignment are a recurring theme, since its approach to Africa and Europe has had major economic and political impacts for the country (Madeira, 2013; Costa, 2007). Cape Verde has also been consolidating its political influence through international organizations such as the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (CPLP), the Macaronesian Euro-Atlantic biogeographic space (Barros, 2020: 93) and the dialogue with the community of the Portuguese-speaking African Countries (PALOP).

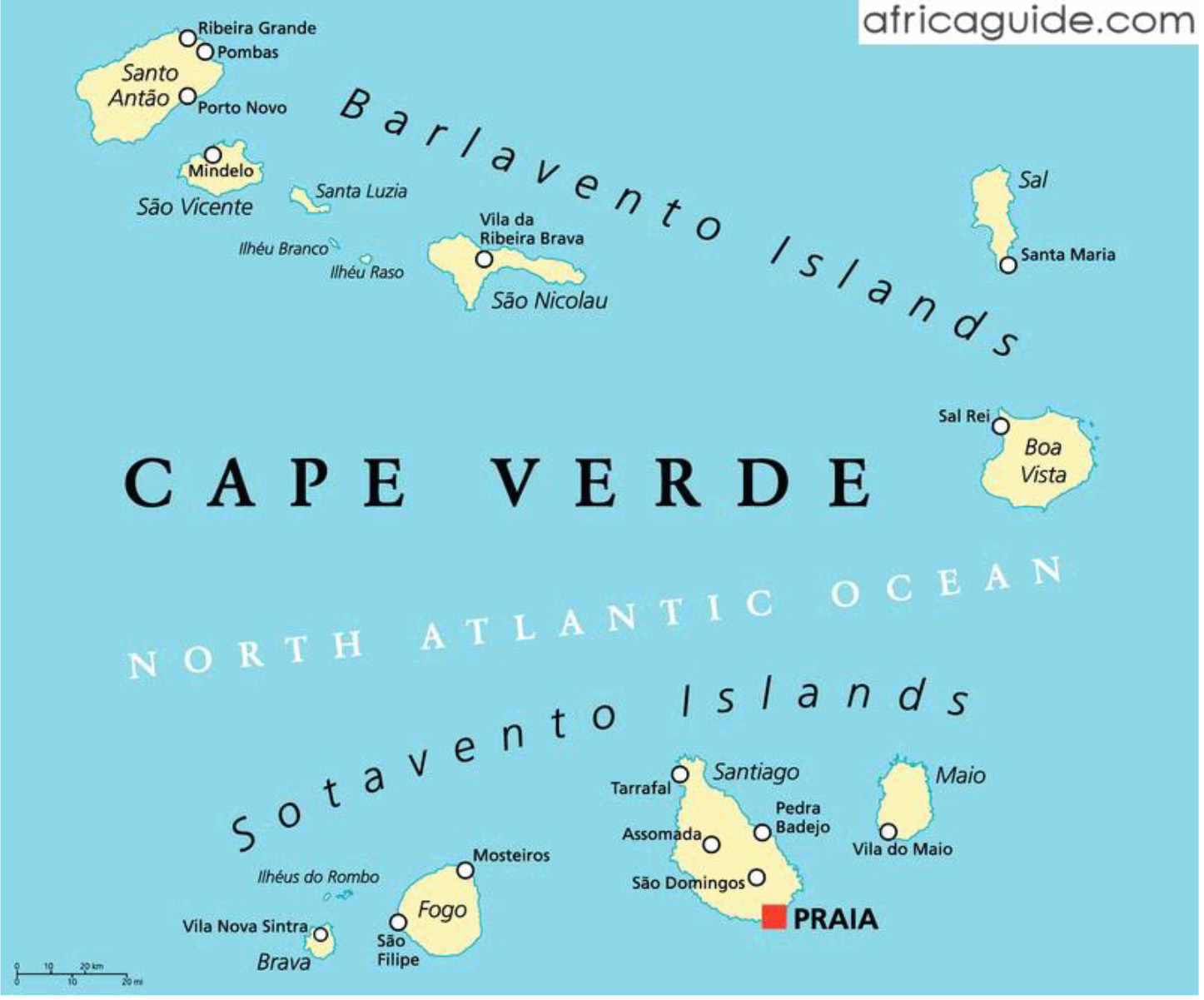

Figure 1: Map of Cape Verde highlighting the capital Praia

In terms of international insertion, the country is recognized for its good governance within the African context. According to Bruce Baker (2009: 144), good governance does appear to be a significant contributory factor behind Cape Verde’s success, but it is largely an endogenous process rather than an exogenous one. Though the degree of sincerity in the motives driving its governance agenda cannot be ascertained, at the very least it can be said that the political class have recognized that it is in Cape Verde’s self-interest to promote it. Good governance marketing is directly associated with international financing, better negotiation capacity with other countries and potential compensation for the country’s lack of natural resources. In addition to good governance, the archipelago’s focus on its geographic and cultural particularities also constitutes a mechanism for international projection and insertion, mainly in the tourism sector, which is important for the country’s economy, and in relation to geopolitics (Madeira, 2019: 90). Culture has emerged in recent decades as a pillar for economic, political and socio-cultural development, in line with broader agendas such as creative economies and cultural tourism.

Regarding internal administration, Baker (2009: 142) argues: ”inter-island governance is universally prickly when it comes to the distribution of national wealth and development projects”. The difficult coordination between the national and local spheres, an important condition for the implementation of comprehensive and long-lasting projects and policies, is constantly mentioned as an obstacle to development in several areas, among which is the safeguarding of cultural heritage. The context, marked by financial and administrative centralization (Ortet, 2008), is one of asymmetry between the islands, especially with regard to the implementation of projects and access to government institutions, with the exception of the two largest cities, Mindelo (São Vicente) and Praia (Santiago).

In this brief contextualization, oriented to facilitate the reader’s understanding of the context of analysis and not an in-depth historical review, an allusion to the Cape Verdean government regime is also necessary. Until the 1990s, it was marked by the government of PAICV’s single party rule and for its authoritarian stance and alignment with the communist nations of Eastern Europe. Among the main reasons for the political transitions are the collapse of communist ideology and international pressure for political change, the process of economic liberalization, the internal conflicts within the party, the troubled relationship between the government and the Catholic Church (a prominent institution in the constitution of Cape Verdean society), and the emergence of the opposition, the Movement for Democracy (MpD) (Barbosa, 2020: 20-22). The establishment of a multiparty system, however, has been characterized by bipartisanship in which the aforementioned parties alternate in power, undermining the durability of policies and projects in various sectors, including culture.

This article explores the friction between the rigid institutional and international guidelines, headed by UNESCO, and the specificities of national and local contexts. As part of this, alongside the greater centrality given to state practices, the problem of community involvement is also examined as a fundamental factor in addressing the following research questions: How does an archipelagic country, with few natural resources, involve itself in the global system of heritage preservation? How does the relationship between national and local governments, a significant one in an archipelagic context, take place? What does this specific case reveal about the gap between scales and stakeholders in this system? And, finally, do the positions adopted by the communities and the country reveal long-term governance strategies that simultaneously comply with community expectations and the insertion of Cape Verde into international heritage networks?

This article is structured according to the four main axes of the case study: first, the asymmetries in ICH governance; second, the potential long-term policies and resolutions carried out at national and local levels; third, the documentation of the political, institutional and legislative mechanisms implemented by the Cape Verdean state since its entry into the ICH global conservation system; and fourth, the analysis of the gaps, outcomes and opportunities configured in this specific context. The article concludes with a discussion of case study implication in relation to the diversification of governance models regarding ICH and of the geopolitical contexts commonly analysed in Critical Heritage research.

ICH and Governance: a matter of perspectives and scales

The establishment of a new global understanding of heritage is observed as a long historical process. Even though in the scope of this article it culminates in the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003), it relates to many other agendas (Aikawa, 2004). The concept of safeguarding cultural assets gained prominence in the post-World War II era and became more complex throughout the second half of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries. Important factors from the post-war era included the need to guarantee cooperation between countries as a means of maintaining the armistice and the social nostalgia for the pre-conflict past, and these were reflected in the creation of international organizations such as the UN and UNESCO and in the heritage safeguarding regime through notions such as shared responsibility and “heritage of humanity”.

Japanese and Korean policies of the post-World War II period were also important in the conceptualization of ICH. They aimed at protecting exceptional cultural practices and expressions and the traditional knowledge that was slowly disappearing as a result of westernization (Alivizatou, 2008: 45-46). The first mention of the concept of cultural heritage appears in the UNESCO Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in Situation of Armed Conflict (1954), but until the mid-seventies the agency, was more attentive to the protection of cultural property than to safeguarding practices. Full globalization of the heritage safeguarding regime took place in 1972, with the publication of the Convention for the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage, in which the theme of heritage safeguard reached a universal status and institutionalizing practices such as listings (World Heritage List) and local and national safeguarding guidelines became central aspects of this shared cultural policy.

Despite the agreement there was continued lobbying for the scope of the policy to be extended on the part of countries whose participation in the heritage regime was hindered by the limitations of the conceptualisation of heritage that focused exclusively on material culture. Thus, between 1972 and 2003 different attempts to re-signify the concept appeared in documents such as the Recommendation for the Safeguarding of Traditional Culture and Folklore (1989) and in debates such as the Conference for the Safeguarding of Traditional Cultures (1999). This contributed to the conceptualization of ICH as adopted in the 2003 Convention. Other documents such as the List of Masterpieces of the Oral and Immaterial Heritage of Humanity (2001) and the Living Human Treasures programme (2003) are further evidence of this gradual reconsideration of the intangible aspects of culture and their centrality in combatting the effects of accelerated globalization in traditional cultural expressions. In 2003, the Convention was published and its high level of acceptance in the international system surprised UNESCO and its Intergovernmental Committee for ICH Safeguarding. Regarding its endorsement and institutionalization, Hafstein (2014: 504) states: “In this, it repeats the international success story of “cultural heritage” itself, propounded by the 1972 convention, not only as a term but as a system of values, a set of practices, a formation of knowledge, a structure of feeling, and a moral code”.

ICH is defined by the Convention (UNESCO, 2003, art.2) as:

“…the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage. This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity.”

From this definition interesting governance aspects emerge in the scope of heritage safeguarding, among which are the centrality of community participation in the elaboration of safeguard dossiers through the methodology of the “community inventory” (ibid., 2003, art. 15); and the recognition of the role of these individuals in the success of the safeguarding, given the direct relationship between the transmission chains and the embodied aspect of ICH. It is manifested in different domains such as “(a) oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage; (b) performing arts; (c) social practices, rituals and festive events; (d) knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; (e) traditional craftsmanship ”(ibid., 2003, art.2) Along with the high level of adherence to the Convention, this broad scope of ICH has helped to transform it into a mechanism that assumes discursive, performative and political power at different scales. Its complex consolidation serves to initiate the financial, cultural, discursive and political flow that Ahmed Skounti (2017: 61) defines as the ICH system: “a constellation of actors either on the local, national, or international levels who contribute, in different ways, to its implementation”.

As a result of this ratification by a large number of states and the consequent reinterpretations of the text at national and local scales, many interdisciplinary analyses emerged that constitute a critical turning point of heritage studies (Kolesnik and Rusanov, 2020). Issues related to intangibility, authenticity, representativeness and political power have been extensively discussed in considerations that observe the role of states in such safeguarding processes (Bendix et al., 2013), as well as the symbolic impact of these processes on the relationship of communities with safeguarded heritage (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, 1995), the dissimilarity of expectations between the stakeholders and scales involved (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, 2004) and, more generally, an understanding of the heritage regime as a discursive practice that legitimizes specific versions of the past, shapes the present and impacts the future.

In this sense, archaeologist Laurajane Smith (2006: 29) recognizes the existence of an “authorized heritage discourse”, highly dependent on the institutionalization of safeguarding measures and framed by the 2003 Convention guidelines. In this sense it is part of a policymaking pattern that limits the epistemological discussions of heritage, as well as the “changes in heritage management and planning practices” (Smith and Waterton, 2012: 153). For example, the commercialization of cultural practices, when the direct relationship between heritagization, tourism and creative economies is properly observed, may also generate concern regarding the authenticity of the practices and their spectacularization. The marketable aspect of the ICH generates complex differences regarding its governance (Geismar, 2015) and intellectual property.

As Wu and Hou (2015: 39) point out: “Heritage is not an objective entity waiting to be discovered or identified; rather, it is more useful seen as constituted and constructed (and, at the same time, constitutive and constructive).” In other words, the increase in case studies and perspectives that focus on interpretation of the Convention and the relationship between the scales involved, as well as the discursive power of the ICH in different locations, are important to the creation and identification of new political regimes and paradigms of heritage governance on different scales. Also, the recognition of the bottom-up impact on this global regime can only be observed via particular cases. The instrumentalization of the concept of ICH by communities and groups, by nation states and by international organizations rectifies, at times, modern rhetoric such as “culture as a resource” (Hafstein, 2014: 503) and as a pillar for development. Specific governance patterns must be observed, as well as geographical particularities. In the case of the African continent, for example, heritage safeguarding is recognized as an important vehicle for development through community training and also tourism.

In order to observe the overlapping relationship between ICH and governance properly, an understanding of this category as a mechanism of power, and even as an international soft power tool (Schreiber, 2017), is a fundamental aspect in questioning the political and economic processes that it involves (Bendix, 2008). The interdisciplinary project UNESCO Frictions1 is an example that:

“explores cultural heritage policies in the era of global governance, focusing on their most recent and debated domain, that of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH), and on its controversial key development, namely, the “participation” of “communities” in heritage identification and selection. (…) An ethnographic exploration of complex world governance sheds light on the interactions of particular actor networks in observable situations across multiple scales.”

Different critical lenses and governance theories have been applied to the observation of heritage and culture management, such as global, international, multi-level, systems, participatory, collaborative, and good governance, among others. Considering that three different scales referring to the ICH category emerge from the Cape Verdean case examined in this article, and given the complexity of the networks established between them, the analysis adopts a position similar to that of the UNESCO Frictions project and considers the centrality of global governance as a starting point. However, it is not only centralized in the international system, but also in the relations between the national and communal scales and their impact on such a global system.

According to Seong-Yong Park (2013: 2-3), author of On Intangible Heritage Safeguarding Governance: An Asia-pacific Context, ICH governance can be defined as follows:

“…an analysis of governance focuses on all the actors involved in the formal and informal decision-making processes, the decision implementation, and the formal and informal structures established to handle such decision-making and implementation. Governance within the intangible heritage field is described as a comprehensive system that relates to safeguarding and promoting ICH at both the national and international level. It includes various legal, political, and administrative structures that the World Humanity Action Trust describes as ’the framework of social and economic systems and legal and political structures through which humanity manages itself’.”

To this definition, here utilized as a theoretical framework of analysis, it can be added that, although departing from the 2003 Convention and UNESCO’s guidelines, specific connections between national and local spheres are also observed, in order to address heritage protection beyond its institutional domain. It is also considered that the analysis of cultural governance presented in this article considers the structural, procedural, multilevel and normative dimensions of data analysis and argumentation (Schmitt, 2009).

The Cape Verdean case study

Institutional and legislative background

According to Freire (1993), Martins (2011) and Queirós da Costa (2018), legislative and institutional developments regarding the cultural heritage sector in Cape Verde intensified only after its independence. One of the first institutions responsible for safeguarding and documenting cultural practices was the Direcção-Geral da Cultura, founded in 1978. Reflecting the long process of political consolidation of the country, the institution, considered as the embryo of the current National Heritage Institute (IPC-CV), underwent numerous transformations in nomenclature, guidelines, political alignment and management throughout its existence to 2014, the year of the IPC-CV’s establishment. Although the documentation of this evolution is not a central aspect of this analysis, it must be noted that many of these changes were oriented by the bipartisan political system and the political interests of the parties in question. The ethnographic investigation carried out at the IPC-CV was focused on the activities of the “Directorate of Intangible Heritage” (DPI), even though the institution’s organization chart provides for collaboration between departments. In addition to the daily participant observation at the institute, research activities included the observation of the development of safeguarding plans, interviews with staff members and archival research aimed at a better understanding of institutional gaps and monitoring the communities involved in the safeguarding processes.

In terms of institutional evolution, the archipelago’s approach to the international guidelines is easily observed through its policies and statutes. In 2020, for example, the statutory review of the IPC-CV attributed to DPI the responsibility for “safeguarding, enhancing and promoting intangible cultural heritage in its different domains”. This was a different proposal from the 2014 statute guidance, in which DPI coordinated “sociocultural research in compatible domains”, the main areas being designated as historical research, oral traditions and applied linguistics. Through the concepts and discursive practices conveyed, the institution’s tutelage reveals the same alignment: while the Ministry of Culture was historically linked to other agendas such as sports, education and even communication (Martins, 2011), its current constitution as the Ministry of Culture and Creative Industries reflects an alignment with the international tendency of treating culture as a resource. The correlation between culture and creative industries is directly associated with the global agenda of recognition of the role of culture in economic and social development and for the promotion of cultural diversity in an ever-changing and more globalized context. This alignment also reveals the archipelago’s search for the diversification of its fragile economy through the promotion of its cultural specificities and tourist activities, which particularly intensified from 2006 onwards.

Despite its projects and activities on different islands, the IPC-CV is located in the capital Praia and its management, mainly the financial aspect, is characterized as highly centralized. In addition to the already complex relationship between the national and local spheres of government, there is a low degree of autonomy for the diversification of projects and partnerships outside the Santiago-São Vicente axis, these islands having greater prominence due to the concentration of population in the two largest cities, Mindelo and Praia. The country’s insularity has a direct impact on the implementation of development policies, including cultural ones, since there are problems of scale, costs and population dispersion which emerge from the geographic discontinuity, as well as urban concentration and rural exodus (Meneses et al., 2012).

Considering these structural conditions, the recovery of transmission chains and cultural knowledge in different ICH domains can have a positive impact on the reduction of scarcity and on the economic diversification of the country. However, the asymmetries in the implementation of projects, especially those of heritage education, appear as an obstacle to the consolidation of permanent links between communities, institutions and ICH that significantly impact on the economic and socio-cultural dimensions. Another institutional and political problem on the national scale is a linguistic one: while the Portuguese language appears as the official language and, therefore, a communication tool for the elaboration of documents and projects under the scope of the IPC-CV and the Ministry of Culture and Creative Industries, the Cape Verdean language, commonly known as kriolu kabuverdianu, is used by the vast majority of the population in domestic contexts. Bilingualism, although it does exist, does not characterize the sociolinguistic situation of the country, thus making the linguistic barrier one of the obstacles for the approximation between institutions and the population. In the case of ICH safeguarding, this issue is central, since the mother tongue is the vehicle for most of the manifestations and domains that belong to the global definition of ICH.

In the legislative field, the first national framework concerning heritage implemented by the Cape Verdean government was the Lei de Bases do Património (1990) which, according to Queirós da Costa (2018: 283), was deeply influenced by analogous legislation in Portugal, enacted in 1985. This first legislation defines intangible cultural heritage as the constituent elements of collective memory. These elements are exemplified as folklore, oral traditions, language and history as well as all forms of human and artistic creation, regardless of their vehicle of manifestation. Whilst many of the articles presented in this law focus on the preservation of tangible heritage, Article nº 70 is dedicated to ICH and legislates the state’s obligation to promote the safeguarding of cultural practices. The role assigned to the state is very central and there is little reference to other stakeholders who might be involved. Furthermore, the only two domains of protection that are specifically mentioned are the Cape Verdean language and documentational heritage, while all other sections are dedicated to broader domains such as ‘cultural ethnographic and ethnological values’ and ‘endangered cultural traditions’.

The text revision published in 2020, Almost thirty years after the original law a revised version was passed in 2019. This embodies the above-mentioned reframing of the concept of cultural heritage at the international level, but it also explicitly calls for the involvement of other stakeholders in this system, mainly the communities and tradition bearers. Two very important aspects of the new legal regime are directly linked to the ratification of two international binding documents in the intervening years. These are the Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (adopted in 2001) and the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (officially ratified in 2016). Despite being set within a large maritime area, the archipelago, is nonetheless impaired by technical and financial difficulties in exploring the underwater heritage, and in recent years has only been able to do so through international cooperation. Since the first legislative framework was not particularly focused on intangible or underwater cultural heritage – two of the richest and most representative aspects of Cape Verdean culture – it was imperative to have in place stronger legislative provisions to safeguard and advocate against crimes related to theft, destruction, intellectual property and cultural appropriation.

The previous legislation gave the national state almost absolute power over the management of cultural heritage, without considering the various stakeholders involved in the heritagization processes, as well as other nation states and public authorities. For instance, the rights and duties of citizens and communities were not specified, nor was the role played by civil society institutions. Explicit engagement of communities under the new provisions is a clear movement towards a better framed conceptualization of intangible heritage that not only respects the complexities surrounding such social processes and their many scales, but also fits the methodological and theoretical guidelines of the 2003 UNESCO Convention. In fact, Article nº 49 of Cape Verdean law, dedicated to the intangible heritage regime, defines its object and domains according to international policy-making, recognizing five domains of expression: oral traditions and expressions; artistic expressions; social practices, rites and festivities; practices and knowledge related to nature and the universe; and traditional craftsmanship.

In addition to these new standardized categories, the acknowledged legal protection mechanisms and measures are inventories and listings (national and international ones) that fit a “local” or “national” category. This differentiation between national and local intangible cultural heritage represents an interesting dynamic in Cape Verde since the majority of islands have their own geographical, historical, environmental and cultural specificities. The enhancement of local spheres of participation (community and governmental ones) may also prompt a diversification of projects and enhance their durability and success rate.

The archipelago and the ICH system

Cape Verde’s participation in the international system related to heritage safeguarding has intensified in recent years but the country’s attempts to list its cultural heritage reach back further into the past. Since the ratification of the UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage in 1987, Cape Verde submitted different applications to the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, referring to cultural practices such as the music and dance genres tabanka (classified as ‘Intangible Heritage of Humanity’ in 2005) and morna (classified in 2019). Since the focus of this analysis is of ICH-related initiatives, it is important to note that the country’s first attempt at ratifying the 2003 Convention occurred in 2008. In fact, the Convention was recognized nationally but, according to Queirós da Costa (2018) and interviewees, the ratification document was not received by UNESCO. So far, the most plausible explanation found for this mishap is a bureaucratic lapse among the many institutional spheres involved in its submission. In that same year, the first Intangible Heritage Department was also established within the responsible institution, in accordance with the 2003 Convention recommendations, but this department would not gain prominence until 2015.

While the country remained focused on its listings of tangible and natural heritage, UNESCO established a project of capacity building directed at the Portuguese Speaking African Countries (PALOP) that lasted four years (2012-2016). This project, financed by Norway, aimed at elevating the global levels of implementation of the 2003 Convention, as well as seeking to create regional cooperation between Lusophone countries in Africa. According to interviewee Lucas Roque, UNESCO facilitator of the project, this cooperation remains extremely important due to the linguistic isolation of these countries within the African context and for the consolidation of their proximity. The specific case of Cape Verde is clear: the country continues to focus on its historical and cultural proximity to Portugal, rather than participating in the consolidation of cooperation networks in the African continent from which the country could benefit.

Although only implemented in Cape Verde in 2014 due to setbacks in other countries, the project acted as a cornerstone for the insertion of the archipelago into the ICH System. Not only did the official ratification of the 2003 Convention happen alongside the project, but it also contributed to the establishment of methodological approaches to inventorying and safeguarding. The community-based inventorying practices, a central aspect of the text, were established as the official safeguarding measure and the technicians received theoretical and practical training on how to make inventories feasible, how to ensure community participation in the safeguard processes and how to plan and implement a safeguarding project that fits the UNESCO guidelines. By the end of the project, as well as the development of a community-based inventory of the ICH in Ribeira Grande de Santiago, a documentary was released presenting the safeguard processes developed with communities in Cape Verde and Mozambique.

This project was important because of the institutional measures adopted by the country since then, and for the insertion of the archipelago into different regional and international contexts. From 2015 onwards, the DPI became fully operative, and under this direction the List of National Intangible Heritage has expanded to include São João Baptista festivities, morna, tabanka and the Cape Verdean language, while the Olaria de Fonte de Lima (traditional pottery) has been properly inventoried but not yet classified. The official UNESCO report on the project classifies Cape Verde as having one of ”the strongest institutional, technical and legal capacities for ICH management” (UNESCO, 2016: 9) within the PALOPs and as a ”highly efficient project partner” (ibid., 2016: 9).

Since the ratification, the country has been adopting a highly institutionalized and politicized structure of governance of the heritagization processes that fits the “authorized heritage discourse” category and the high levels of bureaucratization of UNESCO. In addition to the adoption of new discursive, legislative and institutional practices, the governmental agencies have been working to adjust the methodological procedures to international guidelines. The country has adopted new research standards focused on the integration between nature and culture on the one hand, and tangible and intangible on the other, all within the scope of “tradisons di tera” – a term in Cape Verdean language that synthesizes ICH. Within these “tradisons di tera” there has been a redirection of data collection to domains such as festivities, musical genres and language.

In addition to the aforementioned classifications, since 2019 morna has been classified as “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity”. In this process, an interesting particularity of the project was the centrality of the Cape Verdean diaspora for the documentation, data collection and the dissemination of information about this musical genre as a constituent part of Cape Verdean identity, both within and outside the islands. The diaspora is an important component of the Cape Verdean socio-cultural fabric, its historical traditions and its geographical circumstances, and as such is an unavoidable characteristic of ICH governance. Another successful safeguarding and revitalization process, especially with regard to community participation, was that of the tabanka festivities, one of its main components being the procession of homage to the saint of devotion. In addition to the recovery of the transmission chains, the bonds between tabanka group members, characterized by mutual aid, have become stronger and the prospects for the survival of the practice have been greatly increased. Community participation can be observed by the wide age range in group membership, as well as by the number of presentations and contexts in which they circulate. The risk of spectacularization of the practice, however, must be consistently addressed.

Finally, another non-inventoried cultural practice that has undergone a revitalization process but for which spectacularization is a threat is batuku, a musical genre based on percussion and singing call-and-response (Nogueira, 2011). The multiplication of groups and the interest of younger generations in the practice are clear, as well as the inclusion of batuku in institutionally organized cultural programmes and its circulation within the scope of international music. The non-institutionalized character of this revitalization is a specific characteristic even though it is currently endorsed by institutions such as the IPC-CV, since it has emerged in large part from the use of batuku in musical production from the 90s (Nogueira, 2011: 82). The distance between the traditional context of batuku and its adaptation to show business highlights the issue of the authenticity of the practices understood as cultural heritage, and the validity of attributing a second life to such practices now that they are interpreted by their bearers in a different way and with added value (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, 1995). In this case the complex correlation between local, national and international scales must be carefully observed due to the aforementioned spectacularization, as well as intellectual property and the adaptation of batuku to the commercial universe.

Who is participating?

As previously explained, each heritagization process originates in a different way. In some of the cases outlined above both bottom-up and top-down initiatives can be identified. This makes assessment of the degree of community participation in Cape Verdean processes a complex task. The definition of community itself is a primary factor in this analysis, given its high degree of subjectivity: in certain cases, such as that of morna and the Cape Verdean language, the community comprises all individuals, inside and outside the islands, that relate to these practices. However, other practices, despite their identification as national heritage, have a more localized character, such as the festivities of São João Baptista. Here the reflection on community participation is based on the general context observed throughout the ethnographic fieldwork, with special attention to issues such as self-awareness, heritage education programmes and the distance between institutions and population.

Communities, or traditions-bearers, are increasingly aware of the attributed value of ICH and the need to safeguard it. Although non-profit or non-governmental organizations have been important partners in the implementation of bottom-up projects in most cases, community participation has grown consistently since the ratification of the 2003 Convention. Such awareness, however, is directly related to the consolidation of national and international guidelines of heritage safeguarding, cultural tourism and the creative industries. The value attributed to ICH does not only translate in the symbolic dimension; the commercialization of cultural practices and its performances also emerges as a great opportunity for communities and individuals affected by the country’s difficult socioeconomic and geographical conditions.

At the national level, the government and the responsible institutions have been working to consolidate awareness through heritage education programmes, promotion of activities and conferences and the attempt to implement them in peripheral or rural areas. Heritage education has been centred on community awareness of the value of their cultural practices and the need to safeguard heritage, but at the same time reflects the “authorized heritage discourse” as it reproduces the conventional categorizations, methodologies and alignments of the international order. Thus, the improvement and diversification of the partnership with local actors has sometimes been hampered by the need for recognition and approval of safeguarding projects and plans by the IPC-CV. Although partnerships might be discursively encouraged, their implementation can be hampered by the institutionalization of the ICH system itself.

On the other hand, as community awareness increases, specific conditions in the archipelago can bring interesting combinations of ICH governance, as well as safeguarding processes. The combination of rich local cultural spheres, given the specificities of each island, and the complex Cape Verdean diaspora, highly connected to the archipelago and its culture, has generated innovative safeguard movements that help to achieve a certain level of autonomy for such groups vis-à-vis state institutions. For this reason, in the long run, heritage education programmes, although institutionally oriented, are central to the diversification of initiatives and to the creation of autonomy within the system itself.

Currently, the degree of political centralization and power is reflected in crucial aspects such as the asymmetry of project implementation between islands and their cancellation due to political interests, and is one of the main obstacles to autonomous community participation and also to the diversification of partnerships with local actors. In this sense, a long-term perspective is essential for the improvement of the processes in question and to enhance the possible innovations in the Cape Verdean case. Thus, even though institutional training and action is central at this stage, there is a need to question which new partnerships are possible in order to address issues such as the high degree of heritage institutionalization and the impact of local scales in the ICH system itself., Despite not providing a definitive answer to these questions, the Cape Verdean case allows us to think about the centrality of community participation, but also about the autonomy of these local actors. In addition, the various dimensions of the definition of “community” in this case reveal its importance for the success of processes and for the integration of peripheral areas into the ICH system.

Problematics and possibilities

From the different scales and perspectives addressed, it is possible to observe some issues related to the governance of ICH and its safeguarding processes. Some complexities in various political agendas emerge from the combination of political centralization and geographical discontinuity. In this case, important variables that limit governance models are the asymmetry of initiatives between islands and the centralization of government agencies on the Santiago-São Vicente axis, alongside the difficulty of diversifying partners, which reflects the complex relationships between the local and national levels of government, and the lack of stakeholder autonomy at the local scale. The high degree of institutionalization is also problematic if we think about communities: awareness is a long-term project and the linguistic issue is a central aspect of it. As long as civil society remains distant from the language used in the publication and organization of heritage safeguarding initiatives, however much community members have participated, the creation of autonomy and the enhancement of participation will be more difficult.

In addition to its symbolic dimension, the ICH category also represents an alternative to economic diversification from local to national spheres. Although the commercialization of culture is a problematic topic, there is a clear motivation that endears ICH to Cape Verdean leaders and to the communities which are aware of the social and economic value of their cultural practices. Although the current social conditions do not allow a final description of the different interests involved, mainly due to the highly dynamic character of the ICH system itself, Cape Verde’s prominence in it is a sign of the creative frictions that emerge from the interaction between scales across the archipelago. At the national level, the success of safeguarding projects and the increase in community participation are also positive examples of movements initiated by the interaction between these different scales.

Thus, the adoption of the ICH discursive practice, the interpretation of the 2003 Convention by the government and the governance of heritage assets reveal multiple potentialities that also impact on the ICH system itself. The diaspora is a dimension to be carefully observed, given the centrality of the communities for the safeguarding of the ICH and for the Cape Verdean identity itself. Diversified governance practices have emerged, and indeed are still emerging, from the circulation of the ICH concept and from its safeguarding processes within the country’s unique archipelagic, economic and cultural reality.

Conclusions

Within the scope of heritage studies, case studies have proven to be a valuable contribution due to the centrality of the local and communal spheres to the processes of heritagization of intangible cultural practices. In this sense, the reflections presented in this article represent a valuable contribution to the understanding of the complexity of the ICH system, perhaps one of the most important spheres of cultural governance currently at global, national and local levels.

From the analysis several useful conclusions can be drawn about the complex interactions between scales involved in the ICH system and the potential creative frictions emerging from them. The involvement of Cape Verde in this system proves that, despite its recent integration, the highlighting of peripheral countries is possible and that this participation is potentially an originator of new standardized practices and processes. The case study also illustrates how the different governance and policy structures required in an archipelagic country compared to a continental one are central to understanding how interactions between scales operate in such circumstances, as well as the nature of stakeholder involvement. Thus, heritagization policies and projects are adapted to the geographical reality and to the problems and potentialities emerging from it, such as the difficulty of cooperation between local and national governments.

Attention also needs to be paid to the gap between different stakeholders’ expectations. While both government institutions and certain communities aim at economic and sociocultural improvement through the safeguarding of intangible heritage, such ambitions can be problematic from the perspective of the authenticity of the practices and the alteration of the relationship of such groups with them, in line with the theoretical framework of critical heritage studies. The creation of long-term bases of awareness reveals, in turn, the increase of participation and autonomy of the communities which, for the governance case in question, may represent a framework of greater proximity between the local, national and international spheres. Such a context, however, is dependent on the improvement of political and social conditions that promote a greater degree of autonomy and that consider the specificities of the country within the international system, as well as its local particularities.

1 Available at: https://frictions.hypotheses.org/ [Accessed: 21/08/21].

The PhD research on which this article is based is funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. (Portugal).

Maria Isabel Lemos, Politics and Displays of Culture and Museology, Department of Anthropology, Iscte – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Avenida das Forças Armadas, 1649-026 Lisboa, Portugal. Email: mariaisabelm.lemos@gmail.com

Lei de Bases do Património – Lei Nº 102/III/90 de 29 de Dezembro.

Regime Jurídico de Proteção e Valorização do Património Cultural – Lei Nº /IX /2019. Available at: http://www.parlamento.cv/GDiploApro3.aspx?CodDiplomasAprovados=80348 [Accessed: 07/08/21]

Aikawa, N. (2004) An Historical Overview of the Preparation of the UNESCO International Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Museum International, 56, 1-2, 137-149. CrossRef link

Alivizatou, M. (2008) Contextualising Intangible Cultural Heritage in Heritage Studies and Museology. International Journal of Intangible Cultural Heritage, 3, 44-54.

Baker, B. (2009) Cape Verde: Marketing Good Governance. Africa Spectrum, 44, 2, 135-147. CrossRef link

Barbosa, G. (2020) A TRANSIÇÃO DEMOCRÁTICA EM CABO VERDE: O CASO DO PODER LOCAL, Tese de Mestrado em Ciência Política – Cidadania e Governação. Lisboa: Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias.

Barros, V. (2020) Cabo Verde e o Espaço Euro-Atlântico da Macaronésia. Debater a Europa, 23, 91-106. CrossRef link

Bendix, R. (2008) Heritage between economy and politics: An assessment from the perspective of cultural anthropology. In: Smith, L. and Akagawa, N. (Eds) Intangible Heritage. London: Routledge, 253-269.

Bendix, R., Eggert, A. and Peselmann, A. (2013) Introduction: Heritage Regimes and the State. In: Bendix, R., Eggert, A. and Peselmann, A. (eds) Heritage Regimes and the State. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press, 11-20. CrossRef link

Bortolotto, C. (2016) At the UNESCO feast: Foodways across global heritage governance. UNESCO frictions. Heritage-making across global governance, 15th February 2016. Available at: https://frictions.hypotheses.org/66 [Accessed: 21/08/21].

Costa, S. (2007) Cabo Verde e a Integração Europeia: A Construção Ideológica de um Espaço Imaginário. Revista Travessias, 8, 111-150.

Freire, V. (1993) A experiência Cabo-Verdiana no domínio do patrimônio. Africana, 1, 65-73.

Geismar, H. (2015) Anthropology and Heritage Regimes. Annual Review of Anthropology, 44, 71-85. CrossRef link

Graham, B., Ashworth, G. and Tunbridge, J. (2005) The uses and abuses of heritage. In: Corsine, G. (ed.) Heritage, Museums and Galleries: An Introduction. London, New York: Routledge, 26-37. CrossRef link

Hafstein, V. (2014) Cultural Heritage. In: Bendix, R. and Hasan-Rokem, G. (eds) A Companion to Folklore. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 500-519. CrossRef link

Hafstein, V. (2018) Making Intangible Heritage. El Condor Pasa and Other Stories from UNESCO. Indiana: Indiana University Press. CrossRef link

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (1995) Theorizing Heritage. Ethnomusicology, 39, 367-380. CrossRef link

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (2004) Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production. Museum International, 56, 1-2, 52-65. CrossRef link

Kolesnik, A. and Rusanov, A. (2020) Heritage-As-Process and its Agency: Perspectives of (Critical) Heritage Studies, Higher School of Economics Research Paper No. WP BRP 198/HUM/2020. Available at: SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3746304 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3746304. CrossRef link

Madeira, J.P. (2019) Política Externa Cabo-verdiana: evolução, perspetivas e linhas de força. Revista de Estudos Internacionais, 7, 1, 87-109. CrossRef link

Madeira, J.P. (2013) África versus Europa: Cabo Verde no Atlântico Médio. Revista de Estudos Internacionais, 4, 1, 46 – 59.

Martins, A. (2011) Legislação sobre a defesa do Património em Cabo Verde (1975-2005), Dissertação de Mestrado em Património e Desenvolvimento. Praia: Universidade de Cabo Verde.

Meneses, A., Ribeiro, F. and Cristóvão, A. (2012) Estados insulares, agendas políticas e políticas públicas: Os casos de Cabo Verde e São Tomé e Príncipe. Configurações, 10, 43-68. CrossRef link

Nogueira, G. (2011) BATUKO, PATRIMÓNIO IMATERIAL DE CABO VERDE. PERCURSO HISTÓRICO-MUSICAL, Tese de Mestrado em Património e Desenvolvimento. Praia: Universidade de Cabo Verde.

Ortet, A. (2008) Desconcentração, descentralização e desenvolvimento local em Cabo Verde: os casos dos concelhos da Praia e do Tarrafal, Tese de Mestrado em Estudos Africanos. Lisboa: ISCTE-IUL.

Park, S. (2013) On Intangible Heritage Safeguarding Governance: An Asia-Pacific Context. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Queirós da Costa, C. (2018) Património Cultural Imaterial: Políticas patrimoniais, agentes e organizações. O processo de patrimonialização do Kola San Jon em Portugal, Tese de Doutoramento em Antropologia: Políticas e Imagens da Cultura e Museologia. Lisboa: ISCTE.

Schmitt, T. (2009) Global cultural governance. Decision-making concerning World Heritage between politics and science. Erdkunde, 63, 2, 103-112. CrossRef link

Schreiber, H. (2017) Intangible Cultural Heritage and Soft Power – Exploring the Relationship. International Journal of Intangible Heritage, 12, 44-57.

Skounti, A. (2017) The Intangible Cultural Heritage System: Many Challenges, Few Proposals. Santander Art and Culture Law Review, 3, 2, 61-76.

Smith, L. (2006) Uses of Heritage. Abingdon & New York: Routledge. CrossRef link

Smith, L. and Waterton, E. (2012) Constrained by common sense: the authorized heritage discourse in contemporary debates. In R. Skeates, C. McDavid, and J. Carman (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Archaeology. Oxford University Press, 153-171.

UNESCO (2003) Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention [Accessed: 07/08/21].

UNESCO (2016) Strengthening national capacities for effective intangible cultural heritage safeguarding in selected PALOP countries: Final Narrative Report. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/projects/strengthening-national-capacities-for-effective-intangible-cultural-heritage-safeguarding-in-selected-palop-countries-00279 [Accessed: 10/08/21].

Wu, Z. and Hou, S. (2015) Heritage and Discourse. In: Waterton, E. and Watson, S. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 37-51. CrossRef link