Abstract

The new Labour government faces numerous, interconnected crises along economic, social and environmental nexuses. Policies intended to address issues such as the cost-of-living, healthcare and housing crises are receiving particular attention. Parties have presented narratives around the ecological crisis, such as a significant expansion of renewable energy and reduction of carbon emissions; these are vital, necessary starting points. However, the current discourse is shallow and fails to grapple with the root causes of an operating system that is ultimately self-terminating. We contend that a truly sustainable and regenerative social-ecological transformation must transcend the status quo and fundamentally shift our ontology (ways of being and relating).

In this article, we explore and advocate for a Rights of Nature (RoN) policy. This would not only involve innovative legal and governance mechanisms to ascribe legal agency to more-than-human actants and incorporate them into infrastructures; it would also support the transition of ontological shifts towards relationships of interdependence and stewardship with the more-than-human world. Here, we review the literature on the Rights of Nature, especially highlighting the River Dôn Project (RDP) as a key case study. We explore the necessity of transdisciplinary collaboration and thinking and explore how the UK could demonstrate alternative RoN realities. We conclude by arguing that projects such as the RDP and broader Rights of Nature must be a critical focus of the new Labour government, to ensure our mutually assured flourishing with nature, rather than our mutually assured destruction.

Introduction

The new Labour government faces a multitude of national and global crises, interconnected along economic, social and environmental nexuses. These include sewage pollution in rivers and waterways (Stuart-Leach, 2023), the rising cost of living (de Hoog et al., 2022), a failing healthcare service (Triggle, 2023) and more frequent and severe climate change-induced weather extremes (Hanlon et al., 2021). The government has announced and started to enact policies that are necessary starting points to address the environmental crises, such as lifting the onshore wind ban and pledging no new oil and gas licences, though the latter already faces contention (Loughran, 2024; Ambrose, 2024).

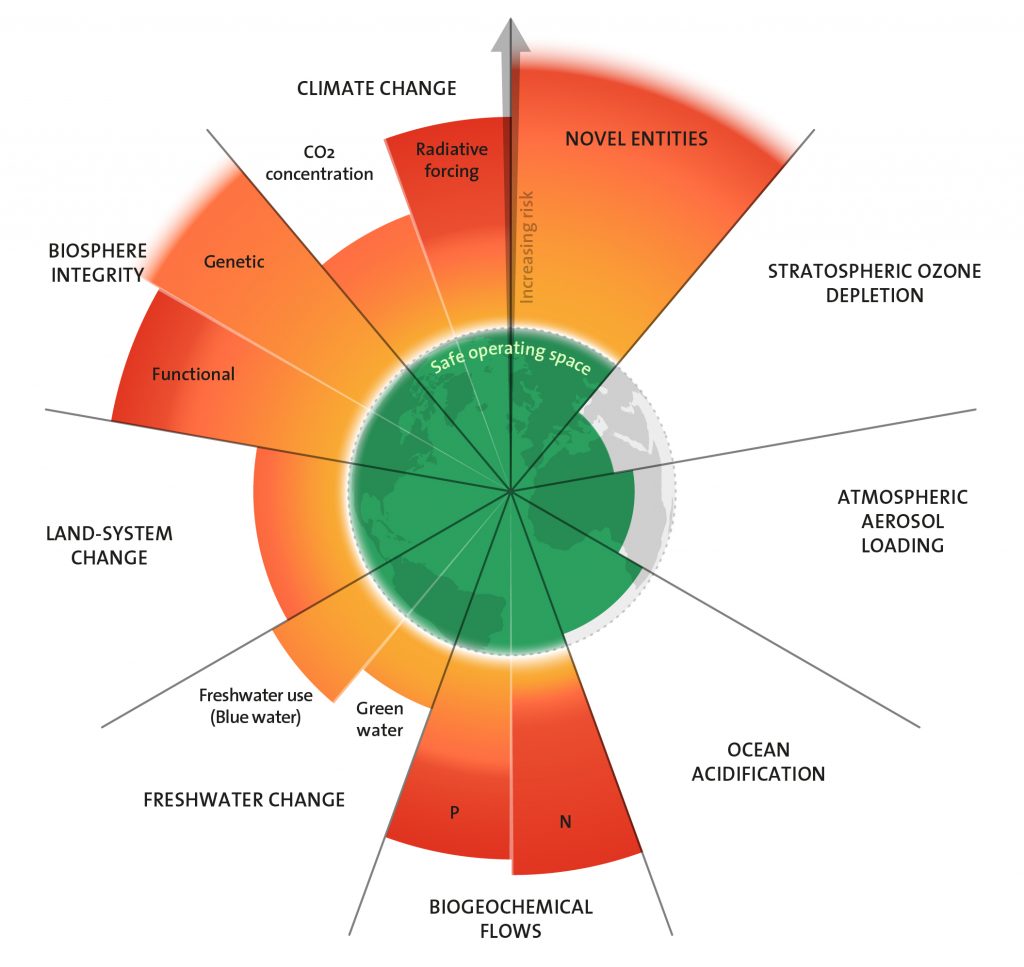

Sadly, these policies fall short in the face of the rapid ecological and social breakdown in the UK and internationally. We are failing to meet many of the basic social foundations conducive to a good life, such as equality, sanitation and energy access (Fanning et al., 2022; Raworth, 2017a; 2017b). Concurrently, at a planetary scale, our economies and societies are surpassing the carbon emissions, nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, and ecological and material footprint required to stay within planetary boundaries (Figure 1) (Richardson et al., 2023).

Ecological economists have long argued that these interconnected failings are highly related to our growth-centric and extraction-based economic model, which positions the environment as an infinite resource to be infinitely extracted from, rather than the finite, exhaustible system we live within (Daly & Farley, 2011; Dietz & O’Neill, 2013; Raworth, 2017a). It is necessary to move to a different kind of economy, informed by a different way of being and a different future (Dietz & O’Neill, 2013; D’Alisa et al., 2015), such as Kate Raworth’s doughnut economics theory (Figure 2) (Raworth, 2017b). We argue that the sustainable social-ecological transformation necessary to safeguard human and more-than-human life on this planet must transcend the extractive, growth-centric status quo and fundamentally shift our ontology.

The contemporary Rights of Nature (RoN) movement, influenced by Stone’s (2010) ground-breaking work and expanded through social theory, both works within and challenges traditional legal paradigms by advocating for the representation, or personhood, of natural entities in legal and political spheres; in this sense, RoN can act as a mechanism to counteract anthropocentric modes of governance and investment, facilitating a recognition of nature beyond property ownership and extraction (Athens, 2018). RoN seeks to address political, legal, and ecological issues, including inadequate environmental policies, to circumvent environmental degradation (Talbot-Jones & Bennett, 2022).

RoN enables a suite of policy agendas, political frameworks, and place-based demonstrator projects that could illustrate how ontological shifts can be embedded in enhanced civic infrastructures, governance, and value allocation frameworks, shifting existing trajectories away from self-terminating futures.

A self-terminating system

Global North capitalist systems contain dominant socially constructed collective intelligence systems, such as democracy and market economies (Kenney et al., 2008; Wolpert, 2003). These can be incredibly effective in achieving narrow goals. Still, they facilitate self-terminating outcomes in their failure to account for a diverse set of often planetary social and ecological externalities. For instance, markets are highly efficient in attributing financial value and pricing commodities; this is typically achieved through substitution, with monetary value universally attributed to capital, labour, power, natural resources, and so forth (Daly & Farley, 2011). Through an ecological economic lens, a critical weakness of financial markets is their inability to appropriately value the repair and regeneration of natural resources and ecosystems (Pascual et al., 2023); for instance, a dead tree is valued more than a live tree, despite the net benefits to broader social-ecological systems of living trees.

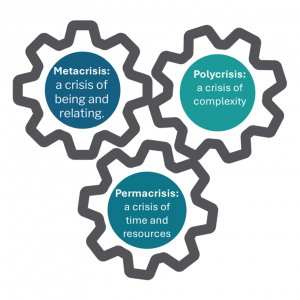

Climate breakdown and burgeoning national and global inequalities show that our socially-constructed collective intelligence systems are insufficient to meet the current suite of interconnected crises and are heading towards collapse as we live on a finite planet and exceed many of its biosphere limitations (Daly & Farley, 2011; Dietz & O’Neill, 2013). Three frameworks show how multiple intersecting crises manifest systemically through dominant collective intelligence systems towards self-terminating outcomes: meta-crises, polycrises and permacrises (Schmachtenberger, 2021), shown in Figure 3.

Metacrisis defines ‘generator functions’ as core processes and systemic behaviours within collective intelligence systems that drive both whole-system and individual behaviours. These are sustained by the system’s deep code (its underlying values and beliefs) and, in complex systems, ultimately combine to create unaccountable externalities. By identifying and targeting the generator functions and deep codes of the current system, change agents can disrupt entrenched patterns and introduce transformative processes that influence the entire system (Schmachtenberger, 2021).

Metacrisis: a crisis in ontology: a crisis of being and relating. Current ways of being and the collective intelligence systems they produce facilitate unsustainability and create existential risk. Much of humanity is constrained by its current ontologies and is unable to imagine alternative realities and thus create sustainable and cooperative systems.

For instance, extractive logics and perverse economic incentives have led us to value trees for what we can extract from them once they are dead, rather than their critical contributions to biosphere health while they are alive. The deployment of unaligned exponential technologies highlights the risk of the Jevons Paradox (Jevons & Flux, 1906), where without societal rules which restrain usage, technological advancements increase resource use efficiency, resulting in lower costs and consequently spurring demand and overall usage. (Jevons & Flux, 1906). Rivalrous dynamics further exacerbate these issues, as competition for finite resources causes securitisation and races to the bottom. These systemic behaviours highlight how our ontologies facilitate unsustainability and create existential risk. We need ontologies that reflect the base reality of our interdependence with each other and the natural world. The impact of these systemic drivers undermines our ability to respond effectively to the crises catalysed through polycrisis and permacrisis (Schmachtenberger, 2021).

Polycrisis: A crisis of complexity and entangled complex systems. The entanglement of social, economic, ontological, technological and ecological challenges leads to multifaceted problems without simple solutions or easily understood accountability, governance and risk frameworks. A tendency to systemically silo problems disrupts accountability and prevents intersectional interventions which could respond to the entangled nature of crisis. This compounds the effect of problems, creating second and third-order ripple effects. The current system lacks the capabilities to adequately value and sense into complex relationships between social and ecological systems, leading to poor decision-making and an accelerated breakdown of social relations and justice. For example, how do we tackle a housing crisis amidst a climate crisis? How do we stop polluting our rivers when the monetary interests of businesses incentivise it? How do we provide social foundations for all in a vulture-capitalist economy? (Blakeley, 2024). How do we ensure mutually assured thriving when the exploitation of more-than-humans is externalised? The polycrisis is thus intersectional and compounding.

Permacrisis: a crisis of time, resilience and resources. The impact of a single adverse event, such as a major flood, compounds the damage of the previous ones, diminishing our ability to recover and respond and negatively impacting our ability to prevent and respond to subsequent crises. These crises often impact foundational economies of food, water, energy, health and land. Thus, as events such as natural disasters, humanitarian and financial crises become more frequent and intense, the risk of triggering social tipping points that worsen and exacerbate the situation and reinforce the current system increases (Klein, 2007). Notably, Meadows et al. (1972) argue we have been in a state of permacrisis for centuries but have yet to (consciously) trigger key environmental tipping points; that said, as aforementioned, we now exceed six of our nine planetary boundaries (Figure 1) (Raworth, 2017a).

The Rights of Nature

The Rights of Nature (RoN) is the notion that non-human entities can possess rights. As Blease (2023) highlights, this is an ancient concept; the Roman moral principle of jus animalium suggests animals held inherent rights alongside humans (Nash, 1989). Numerous Indigenous belief systems (e.g. Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe), have long recognised nature’s agency and intrinsic value, independent of its economic worth (Blease, 2023; Athens, 2018; Watts, 2013). RoN as a ‘policy’ would address political, legal, and ecological issues, including inadequate environmental policies, poor ecological health, insufficient pollution regulation, climate response, and the current legal system’s predisposition to reinforce environmental destruction (Blease, 2023; Talbot-Jones & Bennett, 2022).

Because we have surpassed our philosophical and biosphere limitations for the Enlightenment social contract (Rousseau and Cranston, 1968), there have been significant strides in legally recognising the rights of more-than-human actants. A prominent example is the Te Awa Tupua Act of 2017 in Aotearoa (colonially, New Zealand), which bestowed legal personhood upon the Whanganui River with the Māori people serving as its legal guardians (Evans, 2020). Other examples include the Mar Menor saltwater lagoon in Spain (Winters, 2022), Pacha Mama in Ecuador (Republica del Ecuador Constitución de 2008, Chap.7, Art.21), and all rivers across Bangladesh (Margil, 2020). The granting of legal rights to more-than-human actants in these cases has enabled individuals and communities to demand the enforcement of RoN to protect local ecologies. Simultaneously, such initiatives can explore ecological citizenship and a natural contract (Serres, 1995), recognising a pluralism of relationships between humans and more-than-humans upon which a future of mutually assured thriving is reliant.

Civil society groups and policymakers in the UK are increasingly embracing this paradigm shift (Blease, 2023). There has been an explorative initiative in Lewes (Lewes District Council, 2023), protectionist policies in Norwich (Thompson, 2023) and the albeit unsuccessful bylaw proposal in Frome (Kaminski, 2021) to grant legal status to local rivers. Current examples of river-specific RoN proposals include the River Dart (Dartington Trust, 2023), the River Cam (Limb, 2021), the River Ouse (Lewes District Council, 2023) and the River Don (University of Sheffield, 2022). These initiatives by local authorities, organisations, and community groups indicate that the legal recognition of nature, especially rivers, is gaining traction in the UK.

Case Study: The River Dôn Project

The River Don flows for 114 kilometres through South Yorkshire, UK. Its catchment is home to 1.3 million people and 39 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (Don Catchment Rivers Trust, 2024). As such, it is an exemplar of human existence intertwined with the natural environment. The RDP brings together a range of multidisciplinary partner organisations seeking to shift individual, community, and organisational ontologies by designing and developing novel infrastructures of knowledge, place, and policy. The technologies employed are varied, including peer-to-peer networks, arts and cultural interventions, asset-based community development, public events, generative storytelling, citizen science, sensor networks, machine learning, legal instruments, and RoN campaigning (The River Dôn Project, 2024).

The RDP is a multi-phase and multi-year demonstration and transition project. As such, it benefits from the Three Horizons approach to systems change (The River Dôn Project, 2024). The Three Horizons model is a foresight tool used to explore how current systems (Horizon 1 – the present dominant patterns), through transitional innovations (Horizon 2 – the transition and emerging trends), can be evolved towards a future vision (Horizon 3 – the future, fundamental shifts). Looking across three horizons helps us understand the navigation, subversion, and dexterity required to move between them and the perceptions held in each that must shift. For example, the pursuit of RoN can be considered a Horizon 2 approach in the UK, and it would represent an emerging framework that challenges the current legal and societal norms of Horizon 1 by advocating for a fundamental shift in how we recognise and protect nature. As a Horizon 2 approach, it operates within the transitional space, where innovative legal, ecological, and cultural practices begin to disrupt and gradually transform existing systems, paving the way towards a more sustainable and regenerative future envisioned in Horizon 3. The model fosters future consciousness and guides collective action towards sustainable, regenerative futures (Sharpe et al., 2016).

The RDP will model this through activities informed both by the three crisis frameworks and the framing of RoN. The RDP will develop innovative interfacing and sensing technologies, engage citizens, organisations, and communities, and demonstrate a commons-based approach to governance (University of Sheffield, 2022). The RDP is one example of how RoN could be implemented. Numerous RoN projects work in collaboration with but are distinct from one another (INSRoN, 2022).

A Shift in Ontology

We must build resilience into our collective intelligence systems and foundational economies in response to multiple crises. However, how we respond must embed the foundations of the ontologies that follow. The transition involves reactive measures and proactive strategies to transition from a self-terminating system informed by dominant ontologies of competition, individualism, and separation to one of mutually assured thriving systems informed by interdependence, collectivism, and collaboration. We need policies and infrastructures to support the required transformation of these ontologies and to address the intersectional, compounding nature of crises. RoN could catalyse this trajectory.

Singularly, privatisation and other market-based approaches to ‘managing’ our resources have not only failed to fairly distribute access to resources, but they have also resulted in the significant degradation of our ecologies. This has been exemplified in the case of UK water utilities, which have repeatedly, excessively released sewage and effluent into rivers and the sea (Plimmer & Hughes, 2022). Indeed, the Environment Agency (2023) cannot identify a single river in England with good ecological status. If we were to incorporate the whole system cost of this degradation, utility companies would no longer be viable (Lawson et al., 2023).

Certainly, nationalisation of our natural resources – such as wind, solar, and wave – has a role to play in transitioning towards a more sustainable economy and society, much as the Labour Party argued in its plan for GB Energy (Labour Party, 2023). However, these approaches fail to address the underlying exploitative, extractive relationships our society and economy have with our ecology and more-than-human agents. To justly and sufficiently transition to an economy and society which protects our ecologies, we must move beyond this paradigm (Kojola and Agyeman, 2021).

RoN affords us the opportunity to explore an alternative approach and foster new generator functions. Projects based around the RoN, both globally and within the UK (see above), demonstrate that there is an alternative, but whether new legal frameworks will be enough is an open question (Athens, 2018). How do you interface with complex social-ecological relationships? How could you incorporate nature into the decision-making process? How do you restrain rivalrous dynamics between actors in a system? The RDP is exploring the future rights of nature in South Yorkshire; this is complex, necessary, and innovative.

Transdisciplinarity of Rights of Nature and Climate Responsibility

As we move further into the Anthropocene and social-ecological crises accelerate, we must focus on developing interventions which both repair and regenerate our relationships with each other and the more-than-human. In 2015, the United Nations (UN) and its member states developed and adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Figure 4).

Viewing the UN Sustainable Development Goals as siloed agendas is tempting due to their broad reach; however, further reflection reveals the necessary entanglements between the goals. For example, SDG6 (clean water and sanitation), SDG14 (life below water) and SGG11 (sustainable cities and communities) are intertwined when considering rivers. UN SGD17, partnerships for the goals, addresses the complexity of global sustainability and highlights the need for international, national, and community collaborations.

Transdisciplinary, intersectional collaborations are a cornerstone of sustainable development and advocating for the RoN (Von Wehrden et al., 2019). Transdisciplinarity is complex; working with a range of stakeholders from a range of disciplines is challenging, from differences in lexicons to differing definitions of success (Brennan & Rondón-Sulbarán, 2019). Transdisciplinary collaborations at both national and local levels can be effective, with existing grassroots activist groups well-placed to drive change (Bryan et al., 2019; Moallemi et al., 2020; Jiménez-Aceituno et al., 2020) – although these have had admittedly mixed success (Macedo, 2022).

As Wearne et al. (2023) highlight, bioregionalism emphasises the importance of organising human societies based on specific regions’ ecological and cultural characteristics rather than political boundaries. This approach encourages a deeper connection between local environments and governance infrastructure with the potential to foster more distributed responsibility and stewardship.

Building on the transdisciplinary foundation of the RoN movement, the RDP operationalises bioregional governance through collaborative efforts that blend Indigenous wisdom and scientific methods, challenging the separation between humans and nature (Rozemond, 1998). The RDP focuses on the River Dôn as a bioregional entity, integrating nature-based infrastructures with both human and digital sensing and sense-making technologies, working towards a real-time bioregional AI interface that can surface the complex relationships between citizens, communities, organisations and the more-than-human. This interface could create new insights for choice making and governance and act as a foundation upon which commons and community-based approaches to governance can be explored.

The RDP brings together a diverse range of transdisciplinary partners into an innovative form of multiparty contracting and governance known as ‘Many-to-Many Governance’ (Dark Matter Labs, 2016), designed to foster shared agency, multiple types of capital, trusting relationships, and continuous learning. This type of ecosystem governance is designed to mitigate rivalrous dynamics within transdisciplinary projects and facilitate strategic collaborations in response to complex problems.

Demonstrating Alternative Realities

RoN is gaining momentum in Europe, with the Spanish Act 19/2022 granting legal personhood status to the Mar Menor lagoon (Cabré, 2023). Ireland may follow suit by enshrining the RoN in its constitution (Cullen, 2023). Other international examples include New Zealand (Evans, 2020) and Canada (Berge, 2023). While the UK faces unique challenges, it can draw lessons from jurisdictions that have recognised the RoN (Winters, 2022). Adaptation to the UK context requires careful consideration of local legal, cultural, political and economic factors. Pilot projects offer a practical approach to testing and refining the application of the RoN on a smaller scale before broader adoption.

Britain, as a global leader, should leverage its institutions to integrate RoN. Higher education institutions, for instance, are well-positioned to wrap research, evaluation, and policy-making around community-led projects, ensuring sustainability in funding, visibility in communications, and validity in documentation. In the case of the RDP, curators and (artist-)researchers are positioned to reconceptualise creative work in ways that challenge the neoliberal status quo (Blakeley, 2024), opening up alternative narratives and possibilities. As a demonstrator for RoN, the RDP uses creative methodologies – in the forms of storytelling, art installations, and more – to display the plural nature of our relationships in our ecologies and move beyond our abstract, individualised understanding of our place within these ecologies; in this way, RDP offers a testing ground for new ways of working. Transdisciplinary teams of researchers, knowledge exchange professionals, and academics strive to open up new dialogues with communities and stakeholders along the river and directly via technology with more-than-human actors.

For instance, in the case of the RDP, technology has been employed to create an AI chatbot of the River Dôn, enabling the community to interface with the river and fostering an empathetic relationality; further, this facilitates a form of citizen science, wherein when members of the community ask the chatbot “Hello River, how are you today?”, the chatbot employs data from real-time remote-sensors to tell community members about events occurring in the river, such as: an increase in turbidity, a reduction in dissolved oxygen, and waterflow. Upon receiving this data, community members and organisations can be directed to the point in the river where this problem might be originating, and are invited to submit a form of data (e.g. a photograph of a potential blockage or pollutant) to the chatbot for analysis. This citizen science constitutes a form of ecological citizenship, as it enables community members to participate in data generation on their local ecologies and employ data generated by institutions and organisations such as Yorkshire Water and the Environment Agency. The chatbot can also tell community members about positive events that are occurring, such as an increase in river flies and salmon.

Researchers use their creative practice to create custom-built technologies and visualise global real-time data to create installations that generate social, economic, geographic, and cultural impacts on policymaking in hyper-local contexts (Autogena, 2022). Sheffield Hallam University has played a crucial role in supporting this initiative through a knowledge exchange grant via the Higher Education Innovation Fund (HEIF) to develop an arts and culture strategy. This strategy seeks to nurture the conditions necessary for an ontological shift in how communities perceive their relationships with nature, moving from narratives of separation to narratives of care.

The RDP has benefited from early-stage funding, facilitating numerous aspects of the project, including the curation of a public art installation and exhibition. However, while short, sharp injections of HEIF are essential for early partnership and research network development, multi-year agreements that provide sufficient funding are needed to develop an evidence base to secure larger grant applications. Knowledge exchange professionals help nurture the conditions for collaboration between academics and external partners, enabling research and innovation to have a greater, broader impact on the RDP and its stakeholders. Such exchanges foster meaningful dialogue between the university and external partners for the purpose of ‘experimentally co-shaping new extended and entangled dynamic worlds’ (Emergent Futures Lab, n.d.) fostering the type of ‘civic university’ advocated by Dobson & Ferrari (2023), demonstrating its commitment to ecological justice and positioning itself at the forefront of this transformative legal trend. Appropriate multi-year funding is thus critical for expanding knowledge on RoN in a UK context.

Conclusion

Today, humans are facing a complex entanglement of economic, social, environmental, and health crises, and the coming decade will test our collective ability to respond. We are required at such a moment to reflect deeply on the world views and civic frameworks that have brought us to this point and to navigate the practicality, imagination and urgency of the required transitions. This will require a new nature contract – RoN – that incorporates and appropriately values the complex interdependencies between human and ecological systems. To radically alter our current trajectory – from ecological and social degradation to ecological and social flourishing – we must uproot the systemic drivers, ontologies and corresponding infrastructures that create self-terminating outcomes. RoN should be a core part of this transformation. To achieve this unprecedented systemic transformation we must work collaboratively, across multiple scales and domains, in transdisciplinary approaches and creating governance frameworks that hold multiple types of capital and include both internationally renowned academic institutions and communities and civic organisations with relationships of trust embedded in place. A prerequisite to scaling this transformation outwards is the development of demonstrator projects which illustrate how alternative systems, infrastructures and ways of being and relating could manifest. The RDP is such an initiative, combining innovative approaches to arts and culture, technology, community organising, governance, legal and economic frameworks.

Policy recommendation

Follow international examples and proceed to investigate and implement RoN in the UK. In support of this, expand knowledge exchange funding, such as Higher Education Innovation Funding (HEIF), for civic institutions to facilitate knowledge creation and transfer on RoN.

Alban Krashi, Opus Independents, 71 Hill Street, Highfield, Sheffield, S2 4SP. Email: alban@weareopus.org

Athens, A.K. (2018). An Indivisible and Living Whole: Do We Value Nature Enough to Grant It Personhood? Ecology Law Quarterly, 45(2), 187-226. doi: 10.15779/Z38251FK44.

Ambrose, J. (2024, July 11). Labour faces legal dilemma over plan for immediate ban on new North Sea licences. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/article/2024/jul/11/labour-faces-legal-dilemma-over-plan-for-immediate-ban-on-new-north-sea-licences#:~:text=Labour’s%20pledge%20to%20end%20new,UK’s%20offshore%20wind%20power%20capacity

Autogena, L. (2022). How a film about a planned uranium mine helped empower a small community in Greenland. Sheffield Hallam University. https://www.shu.ac.uk/research/in-action/projects/greenland-at-a-crossroads

Berge, C. (2023, August 14). These rivers are now considered people. What does that mean for travelers? National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/these-rivers-are-now-considered-people-what-does-that-mean-for-travelers

Blakeley, G. (2024). Vulture capitalism : corporate crimes, backdoor bailouts and the death of freedom. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Blease, R. (2023). The Emergence of the Rights of Nature on the UK Policy Agenda: An exploratory study [Masters thesis, University of Bristol]. CrossRef link

Brennan, M., & Rondón-Sulbarán, J. (2019). Transdisciplinary research: Exploring impact, knowledge and quality in the early stages of a sustainable development project. World Development, 122, 481–491. CrossRef link https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.06.001

Bryan, B. A., Hadjikakou, M., & Moallemi, E. A. (2019). Rapid SDG progress possible. Nature Sustainability, 2(11), 999–1000. CrossRef link

Cabré, A. (2023, August 1). The first case recognising the rights of nature in Europe: The Spanish Parliament’s brave step towards ecocentrism. Chemins Publics. https://www.chemins-publics.org/articles/the-first-case-recognizing-the-rights-of-nature-in-Europe-the-Spanish-parliaments-brave-step-towards-ecocentrism

Cullen, L. (2023, August 1). Ireland could become the first country in the EU to enshrine the rights of nature into its national constitution. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cd1d959wkq0o

D’Alisa, G., Demaria, F., & Kallis, G. (Eds.). (2015). Degrowth: a vocabulary for a new era. Routledge. CrossRef link

Daly, H. E., & Farley, J. (2011). Ecological economics: principles and applications. Island Press.

Dark Matter Labs (2016, July 16). Beyond the rules. Dark Matter Labs. https://darkmatterlabs.notion.site/Beyond-the-Rules-19e692bf98f54b44971ca34700e246fd

Dartington Trust (2023, November 19). River Dart Charter at Dartington. Dartington Trust. https://www.dartington.org/about/our-land/the-river-dart-charter/

De Hoog, N., Kirk, A., & Osborne, H. (2022, June 21). How the cost of living crisis is hammering UK households – in charts. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/ng-interactive/2022/jun/21/cost-of-living-crisis-uk-households-charts-inflation?CMP=share_btn_url

Dietz, R., & O’Neill, D. W. (2013). Enough is enough: building a sustainable economy in a world of finite resources (First edition.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Dobson, J., & Ferrari, E. (Eds.). (2023). Reframing the civic university: An agenda for impact. Palgrave Macmillan. CrossRef link

Don Catchment Rivers Trust (2024). The River Don. Don Catchment Rivers Trust. https://dcrt.org.uk/about-the-trust/our-rivers/the-river-don/

Emergent Futures Lab (n.d.). Scaffolding – is this the right metaphor or framework? https://emergentfutureslab.com/blog/scaffolding-metaphor-framework

Environment Agency (2023, July 18). Environment Agency annual report and accounts: 2022 to 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/environment-agency-annual-report-and-accounts-2022-to-2023

Evans, K. (2020, March 20). The New Zealand river that became a legal person. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20200319-the-new-zealand-river-that-became-a-legal-person

Fanning, A., Raworth, K., Krestyaninova, O., & Eriksson, F. (2022). Doughnut Unrolled: Data portrait of place. Doughnut Economics Action Lab.

Hanlon, H, M., Bernie, D., Carigi, G., & Lowe, J. A. (2021). Future changes to high impact weather in the UK. Climate Change, 166(3-4). CrossRef link

INSRoN (2022). Homepage. Nature & Rights. https://natureandrights.org

Jevons, W. S., & Flux, A. W. (1906). The coal question: an inquiry concerning the progress of the nation, and the probable exhaustion of our coal-mines (Third edition.). Macmillan.

Jiménez-Aceituno, A., Peterson, G. D., Norström, A. V., Wong, G. Y., & Downing, A. S. (2020). Local lens for SDG implementation: Lessons from bottom-up approaches in Africa. Sustainability Science, 15(3), 729–743. CrossRef link

Kaminski, I. (2021, July 17). Laws of nature: could UK rivers be given the same rights as people?. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jul/17/laws-of-nature-could-uk-rivers-be-given-same-rights-as-people-aoe

Klein, N. (2007). The shock doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism. Macmillan.

Kenney, E.J., Denyer, N., Easterling, P.E., Hardie, P., and Hunter, R. (2008). Plato: Protagoras. Cambridge University Press.

Kojola, E., & Agyeman, J. (2021). Just Transitions and Labor. In Schaefer Caniglia, B., Jorgenson, A., Malin, S. A., Peek, L. A., Pellow, D. N., & Huang, X. (Eds.). Handbook of environmental sociology. (pp.115-138). Springer. CrossRef link

Labour Party (2023, September 28). Labour’s plan for GB Energy. The Labour Party. https://labour.org.uk/updates/stories/labours-plan-for-gb-energy/

Lawson, A., Isaac, A. and Laville, S. (2023, June 28). What went wrong at Thames Water – and what could a bailout look like? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/jun/28/what-went-wrong-at-thames-water-and-what-could-a-bailout-look-like

Lewes District Council (2023). Council passes first ever Rights of River motion in England, Lewes and Eastbourne councils. https://www.lewes-eastbourne.gov.uk/lewes-district-council-news/council-passes-first-ever-rights-of-river-motion-in-england/

Limb, L. (2021). River Cam becomes first UK river to have its rights declared. Cambridgeshire Live. https://www.cambridge-news.co.uk/news/cambridge-news/river-cam-becomes-first-uk-20876969#

Loughran, J. (2024, July 9). Labour lifts nine-year ban on onshore wind farms. Engineering and Technology. https://eandt.theiet.org/2024/07/09/labour-lifts-nine-year-ban-onshore-wind-farms

Macedo, P. (2022). Municipalities in Transition: a governance system for navigating transformative change in tipping point times. CrossRef link

Margil, M. (2020, August 24). Bangladesh Supreme Court Upholds Rights of Rivers. Medium. https://mari-margil.medium.com/bangladesh-supreme-court-upholds-rights-of-rivers-ede78568d8aa

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens III, W.W. (1972). The limits to growth. New York: Universe Books.

Moallemi, E. A., Malekpour, S., Hadjikakou, M., Raven, R., Szetey, K., Ningrum, D., Dhiaulhaq, A., & Bryan, B. A. (2020). Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals requires transdisciplinary innovation at the local scale. One Earth, 3(3), 300-313. CrossRef link

Nash, R.F. (1989). The Rights of Nature: A History of Environmental Ethics. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Pascual, U., Balvanera, P., Anderson, C. B., Chaplin-Kramer, R., Christie, M., González-Jiménez, D., Martin, A., Raymond, C. M., Termansen, M., Vatn, A., Athayde, S., Baptiste, B., Barton, D. N., Jacobs, S., Kelemen, E., Kumar, R., Lazos, E., Mwampamba, T. H., Nakangu, B. … Zent, E., (2023). Diverse values of nature for sustainability. Nature, 620(7976), 813–823. CrossRef link

Plimmer, G. & Hughes, L. (2022). Water companies leaked sewage into UK waters 370,000 times in 2021. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/ba1ca703-f962-4f83-b469-dfbbeb7650aa

Raworth, K. (2017a). A Doughnut for the Anthropocene: humanity’s compass in the 21st century. The Lancet. Planetary Health, 1(2), e48–e49. CrossRef link

Raworth, K. (2017b). Doughnut Economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. London, England: Penguin Random House.

República del Ecuador Constitucion de 2008. (2008). Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador National Assembly Legislative and Oversight Committee. https://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Ecuador/english08.html

Richardson, J., Steffen, W., Lucht, W., Bendtsen, J., Cornell, S. E., Donges, J. F., Drϋke, M., Fetzer, I., Bala, G., van Bloh, W., Feulner, G., Fiedler, G., Gerten, D., Gleeson, T., Hofmann, M., Huiskamp, W., Kummu, M., Mohan, C., Nogués-Bravo, D. … Rockstöm, J. (2023). Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Science Advances, 9(37). CrossRef link

Rousseau, J.-J., & Cranston, M. (1968). The social contract. Penguin.

Rozemond, M. (1998). Descartes’s dualism. Harvard University Press. CrossRef link

Serres, M. (1995). The natural contract. University of Michigan Press. CrossRef link

Schmachtenberger, D. (2021, June 25). A Problem Well-Stated Is Half-Solved with Daniel Schmachtenberger [Audio podcast episode]. Undivided Attention. Center for Humane Technology.https://www.humanetech.com/podcast/36-unedited-a-problem-well-stated-is-half-solved

Sharpe, B., Hodgson, A., Leicester, G., Lyon, A., & Fazey, I. (2016). Three horizons: a pathways practice for transformation. Ecology and Society, 21(2), 47. CrossRef link

Stone, C.D. (2010). Should Trees Have Standing?: Law, Morality, and the Environment (3rd Edn.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stockholm Resilience Centre (2023, September 13). Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Stockholm Resilience Centre. https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

Stuart-Leach, F. (2023, March 6). How sewage got into UK rivers and seas, and how to fix it. Greenpeace. https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/news/raw-sewage-discharge-water-pollution/

Talbot-Jones, J. & Bennett, J. (2022). Implementing bottom-up governance through granting legal rights to rivers: a case study of the Whanganui River, Aotearoa New Zealand. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 29(1), 64-80. CrossRef link

The River Dôn Project (2024). The River Don Project: A community-led environmental initiative. The River Dôn Project. https://www.theriverdon.org/

Thompson, G. (2023, June 24). Green councillors bid to get River Wensum rights rejected, Norwich. Evening News. https://www.eveningnews24.co.uk/news/23609191. green-councillors-bid-get-river-wensum-rights-rejected/

Triggle, N. (2023, January 7). The NHS crisis: decades in the making. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-64190440

United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

University of Sheffield (2022, August, 22). The Politics and Sociology student working with Sheffield’s ‘Think and Do Tank’ to protect the rights of Sheffield rivers. University of Sheffield. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/politics/news/politics-and-sociology-student-working-sheffields-think-and-do-tank-protect-rights-sheffield-rivers

Von Wehrden, H., Guimarães, M. H., Bina, O., Varanda, M., Lang, D. J., John, B., Gralla, F., Alexander, D., Raines, D., White, A., & Lawrence, R. J. (2019). Interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research: Finding the common ground of multi-faceted concepts. Sustainability Science, 14(4), 875–888. CrossRef link

Watts V. (2013). Indigenous place-thought and agency amongst humans and non-humans (First woman and sky woman go on a European world tour!). Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 2, 20-34.

Wearne, S., Hubbard, E., Jonas, K., & Wilke, M. (2023). A learning journey into contemporary bioregionalism. People and Nature (Hoboken, N.J.). CrossRef link

Winters, J. (2022). Saltwater lagoon granted legal personhood. Grist. https://grist.org/beacon/saltwater-lagoon-granted-legal-personhood/

Wolpert, D. H. (2003, January 23). Collective intelligence. Computational Intelligence: The Experts Speak, 245-258.