Abstract

This article aims to analyse the results of the territorialisation phenomena (Raffestin, 1984; Turco, 1988; Magnaghi, 2001) produced by urban regeneration operations in the two historical centres, Gravina and Matera (European Capital of Culture 2019) located in the south of Italy. These cities have undergone important redevelopment activities that have returned the old town to its citizens, allowing the enhancement of their cultural heritage, also in order to compete in the tourist market. The paper presents a comparative assessment of the two approaches adopted by the administrations of these cities, similar in terms of intangible and material cultural heritage, but belonging to two different regions. The article examines how much these operations have involved the local community by responding appropriately to its needs, contributing to sustainable local development that would ensure lasting effects for the greater part of the citizens, or whether, on the contrary, they are primarily aimed at developing urban cultural tourism (Bianchini and Parkinson, 1993; García, 2004). The results show that an effectively applied legislative framework may facilitate greater local participation by providing solutions that are closer to local needs, and mitigate the negative externalities associated with many urban regeneration processes.

Introduction

Historical town centres between valorisation and new forms of territorialisation

In the collective imaginary, the old town is the emblem of the Italian city, a place of history and culture that appears crystallized in an indefinite era. This image is strongly validated by the increasingly widespread museification of historic centres. Nevertheless, the transformation of humble houses into sometimes luxury residences may contribute to a distortion in the sense of place. An excessive push towards tertiarisation, for example, can cause a break between the community that has abandoned that space and a new form of territorialisation (Raffestin, 1984; Turco, 1988; Magnaghi, 2001) that modifies previous relationships and establishes new ones. This article aims to investigate and compare the changes that have taken place within two small-medium-sized cities in the south of Italy, through urban regeneration activities, which have helped to rehabilitate part of their historical districts. The paper represents a further advancement of the results achieved from a broader line of current research that focuses on issues of local development across southern Italy.

In many Italian cities the improvement of socio-economic conditions during the post-war period led to a discontinuity in housing habits, often causing the emptying of historic centres and thus compromising their effective care and maintenance. An important role has been played by the provision of social housing, which has helped to improve the living conditions of the most disadvantaged families, but has decreed the abandonment, in some cases complete, of the ancient settlements. The set of anthropic acts that intervene on a given place not only modify it, but also invest it with a series of meanings intimately linked to the social group, in turn determining processes of territorialisation. As Magnaghi (2001), following the scheme of Angelo Turco (1988), outlines, these processes of territorialisation occur in three different phases: naming, reification, structuring. The first phase is the symbolic appropriation of the place by giving it a name, then the anthropic acts are manifested in the concrete transformation of the territory, and finally a series of relationships are structured for the functioning of the territorial system. The change in traditional models of building and living often results in a break with the past: in many cases there is no attempt to improve the pre-existing housing conditions, but often people abandon, or are induced to abandon entire neighbourhoods considered not aligned to new and better overall socio-economic conditions. There is rarely a process of transformation that involves a negotiation of meanings and practices; rather, there is a detachment between community and geographical space that often leads to a degeneration of relations between the members of the settled community themselves, which can generate environmental and social degradation.

In this article two examples, one the city of Matera and the other that of Gravina, are used to guide us towards a better understanding of the dynamics triggered by important urban regeneration operations in their historical centres. In the following sections we analyse the theme of urban regeneration in the European context and on the Italian scale. Afterwards we examine how the two cities have faced the challenge of urban regeneration by trying to enhance their cultural heritage, underlining the similarities and differences in terms of urban regeneration management and engagement of the local community, and the effects that the recuperation of the historical centre has had and continues to produce. The crucial issues addressed in this paper aim at understanding whether urban regeneration, observed according to different approaches by the two cities, can bring widespread benefits to the whole citizenry in terms of use of cultural heritage; how the enhancement of cultural heritage can be a way to a lasting local development; the repercussions that these operations have had on residents, trade and tourism; how the existence of a regional law can mitigate the negative externalities that may follow regeneration interventions; and the ways in which the involvement of the community contributes to a response to local needs. The methodology of the research being reported here involved a comparison between two cities with similarities in terms of material and immaterial cultural heritage, in which the historic centres were first abandoned and left to decay and then become a tourist attraction.

In fact, despite the different processes followed by the administrations of the two cities, the results show a common tension for the valorisation of heritage for tourism purposes. These differences between the two approaches are highlighted In the final section; what emerges is that the regeneration of Gravina based on a regional law, the Apulian one, which defines the long-term strategies where the city is requalified mainly for the citizens, and not only to attract tourists, can provide greater benefits to the community than in the case of Matera, where the dynamics in the urban and economic sphere are almost entirely left in the hands of private investors and the market. The regeneration carried out within the framework of a regional law may enable, in the long term, mitigation in the processes of gentrification and expulsion from the historical centres of basic retail businesses intended for residents, as is happening in the city of Matera which, following the designation as European Capital of Culture (ECoC) for 2019, has seen its historical centre turned into an almost exclusively tourist function.

The wider European context

Particularly for small and medium-sized Italian towns, urban regeneration is necessary not only in order to limit the take-up of agricultural land, but also to recover areas of historical and architectural value and return them to residential use. In line with the most virtuous examples of urban regeneration on the European scene (Russi, 2013; Montgomery, 1995) there is a need to aim at an integration between the residential function and services, both primary and also of aggregation and socialization, which the area needs to create a new community. Since 1989, the European Union has implemented instruments and funding for such urban regeneration: Urban Pilot projects, Urban I and II programmes. In addition, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) in the 2014-2020 cycle reserves 5 percent of allocated resources for integrated strategies for sustainable urban development and integrated projects for the regeneration of deprived urban areas (De Gregorio Hurtado, 2017; Boscolo, 2017; De Luca, 2016). These programmes have given a wide margin of discretion to both the member states and the regions, considering urban regeneration as a state competence (De Gregorio Hurtado, 2017; Cento Bull and Jones, 2006).

In addition, the Amsterdam Pact signed in 2016 aims at multi-level cooperation in solving major urban problems. Another contributor to city renewal programmes involves the designation of European Capitals of Culture: this helps to induce cities to proceed towards punctual interventions around the recovery of entire urban areas to enhance the local urban heritage, and as a means of providing a suitable environment for big events (García, 2004). In Italy, the lack of a national legislative orientation has prompted some regions to introduce their own laws, with Apulia being one of the first to do this. In particular, in the Apulian law, the role of the community emerges as a subject widely involved in decisions starting from the initial project idea for a transition from a concept of government to a framework of governance (Cento Bull and Jones, 2006). All these strategies put in place at European, national and regional levels produce effects at local level, but in some cases they may escape the control of administrations or fail to meet the expectations on which they are based. In conceptual terms urban regeneration is not just limited to reclamation and refurbishment of the building heritage, but underpins an idea of rebirth, of new social awareness, of cultural renewal, necessary to try to mend the gap between people, activities and places (Barbanente and Venosa, 2017: 243). These operations are therefore closely linked to the local social fabric and its needs. Often, however, even when starting from an attempt to enhance cultural heritage expressed by local community itself, just an urban facelift is carried out with a territorial marketing strategy, which, although it is able to attract economic investment in the short term, risks not guaranteeing real sustainable benefits (Bianchini and Parkinson, 1993; García, 2004; D’Alessandro and Stanzione, 2018).

Matera: a long evolutionary process

The city of Matera is the capital of the province of the same name and the second largest city in the region Basilicata (about 60,000 inhabitants). Its historical centre overlooks the canyon called Gravina with the districts of Civita, Piano and especially the Sassi (see Figure 1). The exploitation of any available opening in the crags above the ravine produced a phenomenon of widespread underground or cave dwellings, leading to what has been called rock civilization, the main characteristic of this area. Over the centuries these houses were inhabited by the humblest social groups of the population with increasing overcrowding of spaces, and mostly unhealthy conditions because the dwellings are carved into the rock with often just one opening for light and air. This situation remained unchanged until the middle of the 20th century when the city was defined a national shame by Italian politicians (Togliatti and De Gasperi), on the wave of the denouncement contained in the book Cristo si è fermato ad Eboli (‘Christ Stopped at Eboli’) (Levi, 1945), which describes the extreme and precarious conditions in which much of the population in this part of southern Italy lived.

The rise to national news attracted the attention of the central government, which implemented measures to tackle this dramatic situation that cast a dark shadow on a nation that was experiencing a positive trend, the so-called post-war economic boom. Of course, Matera was not the only Italian case characterized by economic and social hardship, but it became the best known, attracting a considerable flow of public funds. One of the significant effects was induced by the national law for the rehabilitation of the Sassi, which triggered a process of evacuation of this urban environment (Law no. 139 of 18-06-1952). The inhabitants of the Sassi were provided with comfortable houses in new neighbourhoods built by major Italian designers. The operation was planned after in-depth studies of the housing situation in the Sassi, conducted by a team of anthropologists, geographers, historians and architects who inspired the construction of new districts that have changed the history of Italian architecture. Some of the new neighbourhoods were built right next to the city centre, whilst others were conceived as suburban villages, designed as self-sufficient units provided with all the services for the functioning of the community: in addition to the apartments, there were schools, a church and shops. The basic idea was to create common spaces in order to re-establish the neighbourhood relations existing in the Sassi (Doria, 2010).

The displacement of the population was followed by a period of total abandonment of the cave dwelling neighbourhoods, a period in which there was an intense city debate on the future of the empty houses: for example, the idea of transforming part of the area into a museum of rural civilization began to emerge (Pontrandolfi, 2002; Mirizzi, 2005).

More than thirty years after the resettlement, a plan for the management of the Sassi was finally approved, defined as a strategy for the recovery of the residential function of the neighbourhoods (Law 771 of 1986). Almost all of the Sassi’s housing belongs to the Italian State, given in concession to the Municipality of Matera, and this made it possible to give the houses in sub-concession to private individuals for a period of thirty years in exchange for an agreed and anticipated rent which also covered the costs of their renovation. The opportunity was mainly taken up by the upper middle class, intellectuals and citizens who participated in the (partly abusive) occupation of some houses. Some buildings were also intended to accommodate artists who wished to move their activities and residence into the historical centre. This operation produced a sort of gentrification oriented by the public sphere but also participated in by the community, which led to the revitalization of these rare and evocative environments, finally re-inhabited, and which contributed, more than symbolically, to erase the feeling of the entire neighbourhood being an inanimate village. This first recognition of the functional and symbolic value of the excavated houses was followed by the city’s commitment to apply for UNESCO World Heritage Site status, obtained in 1993.

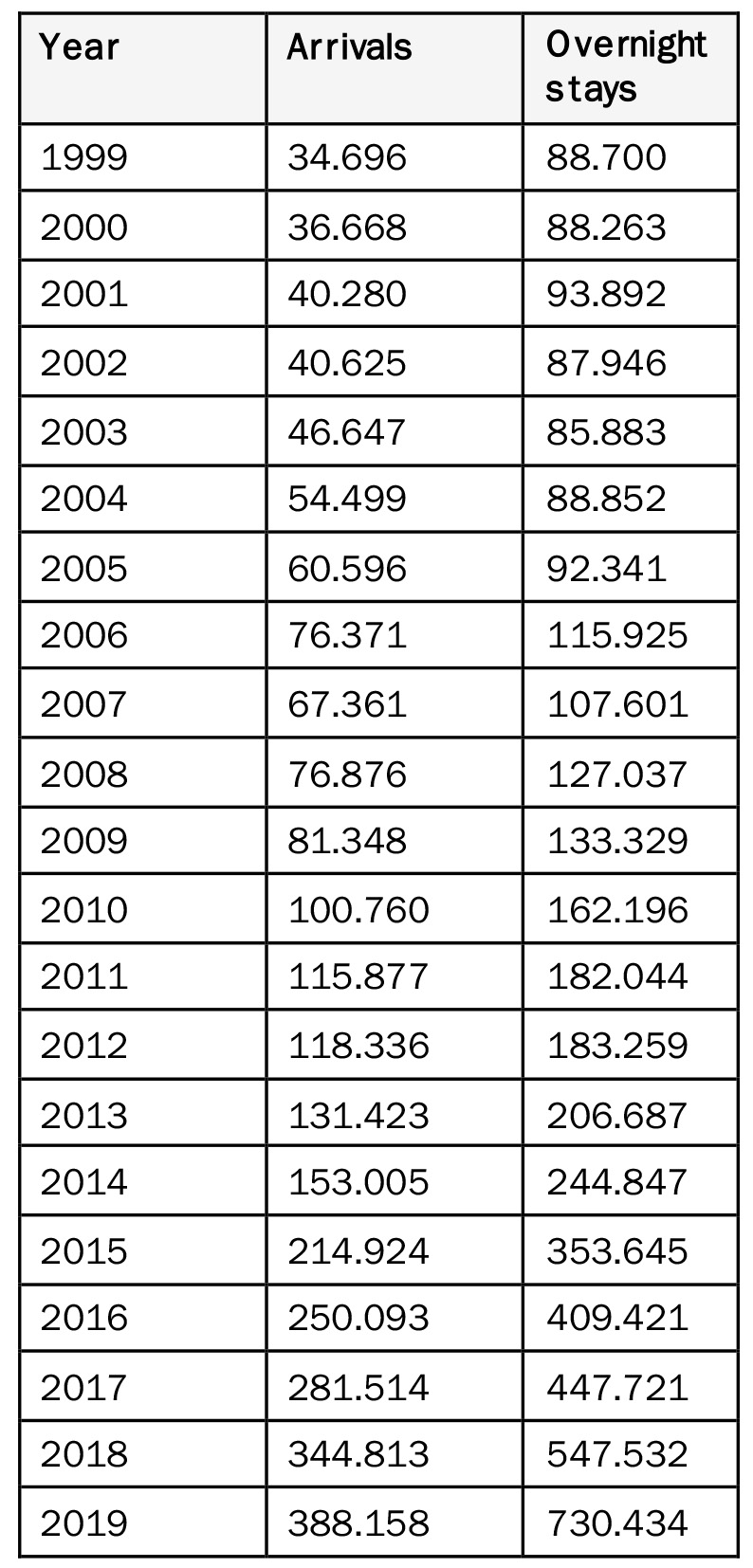

After this milestone, the Sassi area has undergone a fervent renovation of its houses. Families have returned to live in the neighbourhood, despite the objective discomfort already mentioned and the lack of primary services such as neighbourhood shops. At the same time, the area began to attract pioneering tourism, reinforced also by the worldwide publicity given by the film The Passion (2004), shot in Matera by Mel Gibson (see Table 1 for the growth in visitor numbers).

Thus, the local population has begun to see tourism as an opportunity for economic development, transforming their homes into bed and breakfasts and holiday rentals. On the 17th October 2014 the city received a second international award: Matera was designated ECoC for 2019.

Today the Sassi are certainly the biggest attraction, but also an open problem: depopulation by ordinary residents has restarted and the neighbourhood is flooded with hotels, B&Bs, souvenir shops and restaurants, risking a distortion in the perception of the place and causing a loss of memory. The historical centre consisting of the Piano and the Civita have experienced a similar destiny (see Figures 2, 3 and 4). After the designation of Matera to ECoC, the city has registered a considerable increase in visitors, from 153.005 arrivals in 2014 to 388,158 in 2019, and from 244.847 to 730,434 overnight stays (Apt Basilicata), while accommodation capacity has increased from 2,908 in 2014 to 6,566 in 2019. In particular in the Sassi are located 308 hospitality activities, mainly holiday homes (154), followed by room rentals (71), B&Bs (59), hotels (20) and others (4).

Moreover, in the short period between 2015 and 2018 61 new commercial activities have arisen in the food and drink sector in the Sassi (Albolino et al., 2019: 176) mainly for tourists: bars, restaurants, trattorias, some of which also sell typical food and wine products.

While the local public administration supported the candidacy for the ECoC, helping to trigger the major changes resulting from the nomination, it has not played a decisive role in managing the developments that have taken place at city level. With considerable delay for the provision of urban infrastructure also financed by European, regional and municipal funds, at the start of 2019 the city remained as something of an open construction site where visitors were welcomed in a train station still to be completed, parking areas were undersized compared to the needs and small work-sites were spread throughout the city centre, causing much inconvenience to tourists, but especially to the residents. Moreover, the management of economic dynamics was left almost entirely to the initiative of local and non-local entrepreneurs. Considerable private investments were directed towards the constantly growing tourism, concentrating the city’s economy more and more in a single sector (about 40 percent of employees work in the service sector, according to Albolino et al., 2019: 171), and therefore exposed to the fluctuations of the tourist market.

Furthermore, this is short-term tourism, as shown by the data on the average stay that was consistently been around 1.6 days for the 15 years up to 2018, although this increased to 1.9 days in 2019 (based on Apt Basilicata statistics). In other words, it is likely that the economic benefits from tourism are limited in relation to the number of visitors.

Meanwhile, in terms of intra-urban balance, there is a further disconnection among the areas affected by the new trend and the suburbs (some of them very close to the centre), which present considerable inadequacies of essential services and urban maintenance. The proliferation of commercial activities in the central areas is not observed in the rest of the city, where the inhabitants do not benefit from the effects of tourism, but rather in many cases suffer the consequences, such as routine maintenance and waste collection, which is intensified downtown (due to the increase in tourists and commercial businesses) to the disadvantage of peripheral areas. Although the intention of the ECoC candidacy dossier aimed at providing cultural containers in the suburbs, these have unfortunately not helped to compensate for the lack of services for the citizen in such areas. Similarly, though the community had strongly supported Matera’s candidacy for ECoC, it was not actively involved in the decision-making processes that followed, which were in practice mostly oriented towards the strengthening of Matera as a tourist destination.

The designation of ECoC has undoubtedly contributed to the revitalization of the city, especially from a commercial point of view, but it has also triggered a not easily manageable process of undermining the identity and disconnection among different parts of the city (city centre versus suburbs). In addition, the most relevant phenomenon is the progressive abandonment of the historical city by residents who prefer to transform their homes into tourist accommodation, restaurants or other hospitality activities. Although in 2019 there was a slight increase in the number of recorded residents, which beforehand had been progressively decreasing since 1988, in reality this residence does not correspond to the residential use of the property, which is instead used as tourist accommodation (Albolino et al., 2019). In an overall framework of governance uncertainty, sometimes even displaying contradictory positions (Iacovone, 2018), the whole process may not leave long-term results, as has already happened to other ECoC cities (D’Alessandro and Stanzione, 2018).

Gravina in Apulia: bottom-up regeneration processes

The town of Gravina (Apulia region), with a population of about 43,000 inhabitants, is characterized by a landscape marked by hilly slopes of calcareous rocks (see Figure 5). The hill descends towards the Gravina torrent, which gave its name to the town. Similar to the site of Matera, the historical centre of Gravina extends along the rocky crags above the canyon, where the districts of Fondovito and Piaggio are located, and the inner part of the town where the cathedral stands, which dominates the two districts.

The first stone houses in the districts of Fondovito and Piaggio date back to the 9th and 10th centuries. In the post-war period the quarters were inhabited by the poorest population. The two areas were closed off to the view from the high noble palaces and represented almost two marginal areas, even though they were part of the historical centre, thus reducing the inhabitants to a condition of ghettoisation, as seen in Matera. The historical centre maintains its residential function despite depopulation (319 empty houses) and, unlike Matera, the presence of economic activities, now as at the beginning of urban regeneration, is still limited: there are 61 retail shops and very few craft shops, compared to 1,064 shops in the city of Gravina as a whole (Apulia Region, SISUS 2014: Integrated Strategy for Sustainable Urban Development). In the town, the issue of urban regeneration was raised thanks to a bottom-up initiative about ten years ago, and it is also functional to the administration’s intention to try to enhance its potential as a tourist attraction, also taking advantage of its proximity to Matera ECoC 2019 (located about 15 kilometres to the south).

The spontaneous movements for the protection of historical heritage and the ancient districts of Gravina are part of what the Faro Convention defines as heritage communities: a heritage community consists of people who value specific aspects of cultural heritage which they wish, within the framework of public action, to sustain and transmit to future generations (art.2, para. b). According to Zagato (2015), the Convention focuses on the cultural processes that have generated the cultural products, which represent the heritage to be safeguarded. Cultural identity plays a fundamental role in safeguarding the processes, and communities cannot be excluded when it comes to preserving their cultural heritage. The resulting processes of patrimonialisation respond to a need for self-representation of the contemporary community, which is no longer that of the original inhabitants, but includes the potential cultural and economic value represented today by the medieval settlement.

This is what has happened in the city of Gravina, where the local community supported the city administration in its decision-making processes. In the first phase, as stated by the Apulian regional law Rules for urban regeneration (L.R. 21/2008), the local municipality elaborated an Urban Redevelopment Planning Document (DPRU). This document was the result of several meetings attended by citizens and stakeholders in order to identify the urban areas to be regenerated. The approved DPRU states: The Administration, by enhancing and implementing the spontaneous participation movements activated by the citizens, intends to make participation as one of the cornerstones of the process, considering it a real intangible investment within the Investment strategy of the Integrated Urban Development Plan. It is therefore intended to create a laboratory for participation in regeneration, structured as an urban centre, that will attend the entire regeneration process (L.R. 21/2008, art. 21.3, para. 1).

The DPRU defines as a specific objective: Promoting urban regeneration and the redevelopment of the historical centre, in order to support processes of recovery and redevelopment of the public parts of the historical centres, as an essential condition to allow citizens to benefit from their historical architectural heritage, increasing the sense of belonging and improving the conditions of life.

For this reason, the role of community and citizenship is explicitly established by law itself. Although the participation of citizens in urban regeneration interventions has proven in some cases to be partial and not representative enough (Bailey, 2010), the presence of subjects of active citizenship is promoted and stimulated both through regional law and through meetings organized in different contexts (fairs, oratories, and so on), trying to maximize public involvement. The approval of the DPRU was necessary to participate in the regional call, which aims at the redevelopment of the built environment and outdoor spaces, the protection of the historical-cultural-environmental heritage, the functional and qualitative recovery of urbanization and the fight against social exclusion.

The local administration has defined a first urban project called Gravina RE-SET which consisted of three interventions that, together with a reorganization of public spaces, both aesthetic and functional, planned to provide the district with sub-services to allow improvement of the water supply network, a necessary condition for the settlement of new inhabitants and commercial activities. An integral part of the project is also the creation of an immaterial space, LabGravina2020, dedicated to the illustration of programs, projects, work sites in progress, but also with the commitment to promote a shared vision of urban regeneration. The initiative is mainly addressed to citizens, but also to other stakeholders operating in the area.

Therefore, the community is at the very centre of the processes of regeneration. The innovation of the concerted planning tool comprises co-projecting a development that provides concrete responses to the needs of the communities. It is not a top-down master plan, but this should not appear as a de-planning: as a series of disconnected initiatives in different areas of the city, but it should nevertheless be based on a long-term strategic vision aimed at changing the aspect of the city and at improving the living conditions of citizens (Di Pace, 2014).

In fact, the law refers to wide-ranging guidelines: The integrated program of urban regeneration must be based on a guiding idea in order to orient the process of urban regeneration and connecting different activities related to housing policies, urban planning, environmental, cultural, social and health, employment, training and development (L.R. 21/2008, art. 4, para. 1).

The second phase of the urban regeneration project for the 2014-2020 period, Gravina#Connect, concerns essentially the other historical neighbourhood of the city, the Piaggio district. If the Fondovito neighbourhood has continued to be inhabited over the years, the Piaggio has progressively been abandoned. The entire district was closed by gates (1994) and after numerous buildings collapsed, the doors of the houses were walled up (1995). Looking at the district from the Cathedral’s panoramic viewpoint (see Figure 6), it is impressive to observe how gradually it has lost the appearance of a settlement to give way to the vegetation that has regained ground.

As with the UNESCO site of Matera, the urban context that relies on the ravine edge cannot be considered separately from the naturalistic aspect. The medieval parts of Gravina were founded and developed on the rim of the ravine for its intrinsic characteristics, especially in allowing the defence of the town, but also by structuring its peculiar model of housing. The sides of the ravine are connoted by rocky settlements that require conservation and valorization measures. One of the phases of the Gravina#Connect project will be to restore the relationship between the built-up area and the natural element (Regione Puglia, 2014). It must be said, however, that over the years, the direct relationship between humans and nature has changed, leading to random planting interventions, using non-native species that have altered the ecosystem. The project involves the replacement of conifers planted in the 1950s with native species, in order to avoid visual dissonance and botanical anachronisms. No architect would impose an aluminum frame on a baroque palace (Figliuolo, 2017: 293).

Following the first phase of regeneration in the Fondovito district, the local administration intends to create in the Piaggio the pre-conditions for the habitability of the district, primarily a proper water supply and sewerage system that represents, therefore, a first priority before the settlement of new residents and shops can occur.

The difficulty of intervening in this district is also due to the excessive fragmentation of private property. In fact, the overcrowded houses were often inhabited by several families: the succession of owners has also contributed to further parcelling out the rights of private individuals on each single house. Contrary to what happened in the Sassi of Matera, where the ownership of the houses remained public, the Municipality of Gravina can only intervene in public areas, which are often occupied by the ruins of the collapsed private buildings. The municipal properties that will be regenerated also include the convent of Santa Maria, occupied for a long time by disadvantaged families. The project aims to respond to the housing needs of these vulnerable groups by transforming the former convent into short-term co-housing with projects of social inclusion and work placement. Part of the convent will be turned into a multifunctional and social aggregation area, needed in a historical centre where associative and relational spaces tend to be lacking.

These project indications provided by SISUS denote the adherence of the program lines to the social context: the strategy responds to the identification of an housing problem by providing possible solutions in those same environments now occupied illegally, in a state of decay and without the basic services. This is the result of analyses carried out in the LabGravina2020 created in the first phase of urban regeneration. These measures may help to limit the phenomenon of social replacement that often pushes away residents from the historical city: the real estate value of the convent might have led to a more profitable business such as transformation into a hotel, but the strategy claims to focus on the citizen and the community, beside the tendency towards the tourism market. In the long term, this approach will prove to be far-sighted, especially if the tourism challenge is not won. In fact, the city expected to intercept part of the tourist flows visiting Matera, but in comparison with a doubling of arrivals and presences for 2018 with respect to 2015 in the neighbouring city of Altamura (also in the region of Apulia), Gravina has maintained a relatively stable number of arrivals and overnight stays for the same period (12,097 arrivals and 19,955 overnights in 2015 and 12,602 arrivals and 21,608 overnights in 2018). After the first tranche of urban regeneration in the historical centre there are 11 room rentals and 27 bed and breakfasts out of a total of 64 accommodation activities in city (data provided by the SUAP Office, Municipality of Gravina, year 2018). In the two years immediately following the first phase of regeneration (2016-2017) there have been about 50 changes of residence from other neighbourhoods towards downtown, most of which refer to families with only one member: it is often a registered residence that, as in the case of Matera, does not correspond to the real residential use of the property.

Conclusive observations

Two different regions, two different approaches

In response to the main research questions this section presents a brief discussion and comparison of the two cases. Undoubtedly, the recovery of urban heritage in the two historic centres has helped to save entire parts of the city from degradation, revitalising both the residential and commercial fabric. However, in the case of Matera there is a progressive tendency to enhance the heritage for tourist purposes to the detriment of the residential function, with imbalances both within the historical districts and in the management of the city as a whole. On the contrary, the strategy of Gravina aims to restore cultural heritage, firstly for the citizens, by recreating gathering spaces, social housing, cultural containers, and only afterwards proposing the territory as a tourist destination. According to the latter approach, the whole community is called to benefit from the effects of the valorisation of cultural heritage with a perspective of effective sustainable development that does not aim at territorial marketing as the only economic strategy. This is possible thanks to the regional legislative framework on urban regeneration that, while leaving the community the freedom to decide on a strategy of action, does not completely cede to the market the management of the dynamics triggered by regeneration, as seems to be happening in the case of Matera. The Apulian legislation also attempts to ensure greater responsiveness to the needs of residents through the legitimacy of the community to take part in decisions concerning interventions, starting from the planning stage. In Matera this process seems to be more discontinuous, as it is not always able to involve also those who do not participate in the tourism industry or, on the contrary, suffer the negative consequences. In the two concluding sub-sections we analyse in detail the results of the two different approaches.

Gravina: place re-signification

Gravina is carrying out a process of re-signification of the historical centre. According to Magnaghi (2001), the process of re-territorialization of spaces takes place after the attribution of a new value to places: economic, social or cultural. The places thus acquire a new meaning and are reinterpreted according to it. Private homes acquire a new value (also economic), so the public spaces themselves change their role: the redeveloped space in front of the ravine, in the Fondovito district, after years of abandonment has become a space of sociality dedicated to events, not only for the community of the district, but also for citizens in the rest of Gravina and surrounding towns. The case of Gravina has shown that ancient districts are not to be considered as an appendix separate from the rest of the city, but places that need a new meaning for the community. The functional improvement helps to remove the historical districts from marginality, dictated by difficulty of access and lack of basic services, and to regain a new centrality.

In accordance with the Faro Convention in order to raise awareness and utilise the economic potential of the cultural heritage (art. 10,, para. a), the administration has provided a series of incentives for commercial activities to settle down in the historical centre, in order to take advantage of being located in such an area of cultural and landscape interest.

A few years after the conclusion of the restoration works in the Fondovito district (2015), there has not yet been a significant phenomenon of redevelopment of the area for residential use, although there certainly has been a partial improvement in housing conditions of the neighbourhood. One factor in this is the work required to recover collapsed and derelict buildings involves a significant economic investment, made even larger because the morphology of the area limits the transit of heavy vehicles of construction companies. Therefore, a more immediate return on investment can be expected with the establishment of commercial activities rather than with renovation for residential use only. However, even the commercial activities themselves are scarcely appearing on the scene and the neighbourhood is still far from completely redeveloped, with many buildings still abandoned and in a state of decay.

However, these are processes that take years; at least there are signs that the foundations have been put in place so that there might be a proper management of regeneration dynamics in the future, also thanks to the indications of the Apulian regional law. The real challenge will be to try to repopulate the district through the settlement of new residents, providing them with incentives for the renovation of housing, so that the residential function of the district will be preserved in order to repopulate spaces with a stable community, to ensure that the houses are meant for the residents and not only for tourists (Cappiello and Stanzione, 2018). The example of nearby Matera might on the one hand be stimulating the inhabitants of Gravina to pursue the idea of a cultural tourism, but on the other hand warns against the dangers of possible gentrification. The second phase of regeneration, in fact, by providing the restructuring of the convent for co-housing purposes (in line with the Regional Law, art. 4, para. a), does not deprive citizens of the right to the historical city (De Lucia, 2019), but makes them protagonists and beneficiaries of urban spaces, limiting the prospect of social substitution.

Urban regeneration, therefore, is taking place through an active participation of citizens in the drafting of the DPRU, thanks to the law on urban regeneration that leaves to the municipalities the freedom to direct urban policies and enables them to meet the needs of citizens, also with a view to territorial enhancement. The interventions, nevertheless, are encapsulated within the guidelines established by the Apulian law, conceived to favour the recovery of large areas of the urban fabric, limiting decompensation and aberrations that could derive from the absence of a governance that leaves the strategies and practices of transformation of urban space entirely to the real estate market and to private citizens.

Matera: urban imbalances

In Basilicata region too much is left to the single towns in terms of urban planning, since there is not a regional law such as the Apulian one, which gives concrete indications regarding urban redevelopment. Although originally based on the development of cultural activities linked to the community, here regeneration risks being aimed at increasing urban tourism and not really meeting the needs of residents (Bianchini and Parkinson, 1993; García, 2004). In the specific case of the Sassi, is it possible to refer to resilience where what survives are completely re-territorialized places, which basically succumb to the dynamics of tourist demand? Where the houses once destined for the disadvantaged classes are often transformed into luxury accommodation, inaccessible to those who have lived in poor sanitary conditions in those very environments?

The same may be noted for the economic values reached by the properties which are or are to be used as residences. Are neighbourhoods returned to the community or is the community excluded from them? Are these only spaces that have lost their function and are waiting to be reinvented, according to the current needs that see tourism as a new economic driver? But even in this case it is very difficult to discern any general guideline which precisely identifies a specific target of tourism (cultural and naturalistic, for example), because the region has not implemented a new tourism strategy since 2008.

In addition, it should be stressed that the Faro Convention establishes as a principle a limitation to economic exploitation of heritage: ensure that these policies respect the integrity of the cultural heritage without compromising its inherent values (art. 10, para. c). In this perspective the city of Matera requires the adoption of an overall regeneration strategy shared by different stakeholders which also includes citizens not directly or indirectly involved in activities and services related to tourism; and that is wide-ranging enough to remove the risk of economic monoculture. Only an effective investment aimed at improving urban mobility, providing services and social aggregation spaces to the suburbs may limit the feeling of estrangement that affects those who cross the city from the centre to the suburbs and vice versa.

In addition, during ECoC year, the old town was animated by many structural interventions, events and socializing spaces that attracted hundreds of visitors. While this was a response to the city’s ambition, it also overloaded the historical city with mass tourism, which is difficult to manage in a small-medium-sized city. There are already many examples in Italy that demonstrate how, beyond a certain limit of carrying capacity, it is necessary to decongest historical centres, through laws aimed at containing the impoverishment and the denaturing of the heritage. The year of events comprising Matera ECoC 2019 was conceived around an idea of community festival, but the Matera community seems to have supported the initiatives without being really involved in the strategic decisions on the future of the city and the historical centre in particular. Focusing media, economic and investment attention in the city centre to the detriment of the suburbs in the long term will not lead to a fair distribution of benefits to the entire community. The absence of a regional law on urban regeneration may deprive citizens of spaces in which to express their views on the shared strategy. Why then run the risk of having to deal with the situation ex post? Perhaps there is still time for a change of direction.

Although this article is the result of the joint research of the two authors, direct attribution of authorship of the different sections is as follows. Luigi Stanzione: The wider European context; Matera: a long evolutionary process; and Matera: urban imbalances. Lucia Cappiello: Historical centres between valorisation and new forms of territorialisation; Gravina in Apulia: bottom-up regeneration processes; Two different regions, two different approaches; and Gravina: place re-signification.

Università della Basilicata, Via La Nera 20, 75100, Matera. Email: lucia.cappiello@unibas.it / luigi.stanzione@unibas.it

Albolino, O., Cappiello, L., Iacovone, G. and Stanzione, L. (2019) Profitto e valori: ethos e commercio. Il caso di Matera. In: Viganoni L., (ed) Commercio e consumo nelle città che cambiano. Napoli, città medie, spazi esterni. Milano: FrancoAngeli, 149-192.

Bailey, N. (2010) Understanding community empowerment in urban regeneration and planning in England: putting policy and practice in context. Planning Practice and Research, 25, 3, 317-332. CrossRef link

Barbanente, A. and Venosa, M. (2017) Rigenerazione urbana multiscalare: oltre la città fordista. In: Carta, M. and Lagreca P. (ed) Cambiamenti dell’urbanistica. Responsabilità e strumenti al servizio del paese. Roma: Donzelli editore, 243-249.

Bianchini, F. and Parkinson, M. (1993) Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration: The West European Experience. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Boscolo, E. (2017) La riqualificazione urbana: una lettura giuridica. Urban@it, 1, 1-9.

Cappiello, L. and Stanzione, L. (2018) Rigenerazione urbana e nuove forme di fruizione della città: i casi di Gravina in Puglia e Matera. Urban@it, 2, 2-10.

Cento Bull, A. and Jones, B. (2006) Governance and social capital in urban regeneration: A comparison between Bristol and Naples. Urban Studies, 43, 4, 767–786. CrossRef link

D’Alessandro, L. and Stanzione, L. (2018) Scale, dinamiche e processi territoriali in vista di Matera 2019: riflessioni su sviluppo locale, cultura e creatività. Geotema, 38, 78-90.

De Gregorio Hurtado, S. (2017) 25 years of urban regeneration in the EU/25 anni di rigenerazione urbana nell’UE. Tria, 10, 1, 15-19.

De Luca, S. (2016) Politiche europee e città: stato dell’arte e prospettive future. Urban@it, 2, 1-11.

De Lucia V. (2019) Il diritto alla città storica. Atti del Convegno, Roma, Italy, 12th November 2018.

Di Pace, R. (2014) La rigenerazione urbana tra programmazione e pianificazione. Rivista giuridica dell’edilizia, 4, 237-260.

Doria, P. (2010) Ritorno alla città laboratorio. I quartieri materani del risanamento cinquanta anni dopo. Matera: Antezza Edizioni.

Figliuolo, G. (2017) I Sassi si completano con la natura vivente. In: Mininni, M. MateraLucania2017: laboratorio città paesaggio. Roma: Quodlibet, 292-293.

García, B. (2004) Urban regeneration, arts programming and major events: Glasgow 1990, Sydney 2000 and Barcelona 2004. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 10, 1, 103- 118. CrossRef link

Iacovone, G. (2018) Un patto centro-periferie per la sostenibilità urbana del commercio e del turismo. Presentation to the International Conference Dialogi europei sulla convergenza nei valori, principî, regole e pratiche del diritto dell’economia e dell’impresa, Università degli Studi di Bari “A. Moro”, Taranto, Italy, 11th-14th December.

Levi, C. (1945) Cristo si è fermato ad Eboli. Firenze: Einaudi.

Magnaghi, A. (2001) Una metodologia analitica per la progettazione identitaria del territorio. In: Magnaghi, A. (ed) Rappresentare i luoghi, metodi e tecniche. Firenze: Alinea, 7-52.

Mirizzi, F. (2005) Il Museo demoetnoantropologico dei Sassi a Matera. Genesi e storia di un’idea, presupposti e ragioni di un progetto. Lares, LXXI, 213-251.

Montgomery, J. (1995) The story of Temple Bar: creating Dublin’s cultural quarter. Planning Practice and Research, 10, 2, 135-172. CrossRef link

Pontrandolfi, A. (2002) La vergogna cancellata. Matera: Altrimedia edizioni.

Raffestin, C. (1984) Territorializzazione, deterritorializzazione, riterritorializzazione e informazione. In: Turco, A. (ed), Regione e regionalizzazione. Milano: Franco Angeli Editore, 69-82.

Regione Puglia (2014) P.O. FESR- FSE 2014-2020, Bando pubblico per la selezione delle Aree Urbane e per l’individuazione delle Autorità Urbane in attuazione dell’asse prioritario XII “Sviluppo Urbano Sostenibile – SUS” del P.O. FESR- FSE 2014-2020. ALLEGATO 5 – schema di strategia integrata di sviluppo urbano sostenibile. SISUS Gravina in Puglia. Available at: https://comune.gravina.ba.it/bando-pubblico-per-la-selezione-delle-aree-urbane-e-per-lindividuazione-delle-autorita-urbane-in-attuazione-dellasse-prioritario-xii-sviluppo-urbano-sostenibile-azione-12-1-rigenerazione-urb/schema-di-strategia-integrata-di-sviluppo-urbana-sostenibile/ [Accessed: 04/08/19].

Russi, N. (2013) Dublino, dalla crisi economica alla rigenerazione urbana. Territorio, 67, 115-122. CrossRef link

Turco, A. (1988) Verso una teoria geografica della complessità. Milano: Unicopli.

Zagato, L. (2015) The Notion of “Heritage Community” in the Council of Europe’s Faro Convention. Its Impact on the European Legal Framework. In: Adell, N. et al. (ed) Between Imagined Communities of Practice: Participation, Territory and the Making of Heritage. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press, 141-170. CrossRef link