Abstract

This paper reflects on the changing relationship between faith-based organisations, the state and the market in an age of austerity localism. It argues that, while much of the discourse about faith-based organisations in the New Labour period focused on their participation in government-sponsored regeneration initiatives, recent years have witnessed the emergence of more entrepreneurial forms of Christian social action. Three recent manifestations of this are examined in turn: the ‘fresh expressions of Church’ movement, the growth of social action by large evangelical churches and megachurches, and the emergence of a national market place of Christian community franchises and brands. These developments expose significant differences emerging between faith-based organisations and other third sector organisations. For policy makers and public bodies increasingly having to ‘do more with less’, they raise significant challenges and opportunities.

Introduction

This paper explores the subject of this themed issue through the lens of faith-based organisations. It reviews some of the ways in which the relationship between faith-based organisations, the state and the market is changing and reflects on their significance for wider debates about the third sector. While previous studies have highlighted that faith-based social action in Britain takes many forms and is not confined to any one religious tradition (Jochum, et al., 2007; Jawad, 2012), this paper illustrates the complexity and fast-changing nature of social action within one particular faith tradition, namely Christianity.

The paper begins with a brief review of the literature on faith-based social action from the New Labour period. Here, it is argued that much of the policy and research discourse on faith-based social action in the late 1990s and early 2000s was characterised by an emphasis on faith groups’ usefulness to government. The paper then goes on to suggest that recent years have witnessed the emergence of more entrepreneurial forms of Christian social involvement. Three examples of this are then reviewed and discussed. The paper concludes by reflecting on the significance of these developments for wider debates about faith groups’ relationship with the third sector, the state and the market.

Faith-based social action under ‘New Labour’

Prior to the late 1990s, there had been relatively little policy interest on the role and function of religious or faith-motivated voluntary and community organisations (McCabe et al., 2010: 11; Wier, 2014: 31). However, the role of faith communities rose to prominence in the New Labour period. As Dinham and Lowndes observe, faiths became increasingly seen by government as repositories of resources (such as buildings, staff and networks) in a mixed economy of welfare, and as having an important role in building community cohesion (Dinham and Lowndes 2009: 5-6). This period was a golden age for the third sector (Crowe et al., 2010: 29), with large amounts of public funding available to local organisations willing to participate in government-sponsored community regeneration initiatives. Faith groups that positioned themselves as part of the ‘voluntary, community and faith sector’ were also able to access such funding. Indeed the government’s Action Plan for Neighbourhood Renewal proposed a more pragmatic approach to funding faith groups, acknowledging that faith-based organisations ‘may offer a channel to some of the hardest-to-reach groups’ (Cabinet Office, 2001: 52).

During this period, there were numerous studies of faith-based social action. Many of these were commissioned by faith groups keen to demonstrate their usefulness to government. Within Yorkshire and the Humber, for example, research conducted for the Churches Regional Commission tried to quantify and illustrate the contribution of church-based social action to local communities across the region (Yorkshire Churches, 2002). Similar exercises were also conducted in many other English regions, as well as at a national level (Payne, 2009). Furthermore, many of the academic studies of faith-based social action in this period focused on faith groups’ contribution to New Labour policy agendas (Wier, 2014: 31), for example those around urban regeneration (Farnell et al., 2003), social capital (Furbey et al., 2006) and community cohesion (James, 2007). In summary then, it would appear that much of the dominant discourse about faith-based organisations in the New Labour period was focused around faith groups’ usefulness to government. Such discourse sometimes gave the impression that most faith-based social action was state-funded, though in reality this was probably not the case. Mirroring the wider experience of the third sector (Teasdale et al., 2013: 2; Buckingham, 2012), there appears to have been an emerging bifurcation between a silent majority of ‘below the radar’ (Wier, 2014) faith groups that operated largely independent of government and a relatively small number of more professionally run faith-based organisations that received substantial public funding.

For the purposes of this paper, what is particularly significant from the preceding review is that state-sponsored forms of faith-based social action have received most of the attention from academics, policy makers and leading commentators. Two implications of this for the representation of Christian social action in the New Labour period are highlighted by Wier (2014). First, the picture of Christian social action that emerges from previous studies is one that is:

not radically dissimilar from the practice of other (secular) voluntary and community sector organisations. As Jawad (2012: 558) puts it, contemporary British scholarship ‘implicitly situates religious welfare in the voluntary sphere as part of the mixed economy of welfare paradigm and does not distinguish between secular and religious organisations (Wier, 2014: 31).

Second, and perhaps as a consequence of this, relatively little attention has been given to the place of evangelism and faith-sharing within faith-based social action. Despite some notable exceptions (Cloke et al., 2005, 2007), existing literature frequently paints a picture of faith-based social action which, while rooted in a theological imperative of loving service, contains no discernible element of evangelism (Wier, 2014: 31-2). As we will later go on to see, the emergence of newer ‘entrepreneurial’ forms of faith-based social action appears to challenge such understandings. Before this, however, it is first necessary to provide a brief explanation of how the term ‘entrepreneurial’ is being used.

An entrepreneurial ethos

Discussion of entrepreneurship within the wider third sector often focuses on the phenomenon of social enterprise (Chew and Lyon, 2012). However, with a few notable exceptions (Dinham, 2012: 130-159), the UK literature on faith-based social enterprise is largely underdeveloped. This paper, in contrast, employs a wider conception of entrepreneurship. Drawing on theoretical perspectives from the sociology of religion, it points to the emergence of new forms of faith-based practice that could be said to embody what Warner calls an ‘entrepreneurial ethos’ (Warner, 2010: 154). Within the context of secularisation and an open religious market, Warner reviews evidence from the United States which suggests that ‘continuing entrepreneurial innovation is essential for any kind of religion to sustain market share’ (Warner, 2010: 153). He then goes on to identify the following characteristics of an entrepreneurial ethos exhibited by various new forms of faith-based practice:

- Clear and compelling vision;

- Measurable, annual goals;

- Focus upon a defined, target audience who are the primary market;

- Marketing that defines a brand, and secures and sustains public profile;

- Adaptive management structures that are open to change;

- Rapid adoption of new technologies, harnessed to the vision;

- Charismatic leadership, conveying vision and empowering the team;

- A determined drive towards increasing heights of achievement.

(Warner, 2010: 154)

Significantly, Warner suggests that many of the most prominent examples of entrepreneurial religion are from the United States and that an entrepreneurial ethos may be inconsistent with ‘the dominant European religious idiom of the centuries old parish church’ (Warner, 2010: 154). Nevertheless, there appear to be signs that ‘even in the context of the United Kingdom’, entrepreneurial religion can ‘enjoy rapid and exceptional growth’ (Warner, 2010: 154). Within this context, the rest of this article explores three case studies that highlight the significance of an entrepreneurial ethos for new and emerging forms of Christian social engagement. The selection of these case studies has been informed by the author’s experience as a practitioner, researcher, consultant and observer of Christian social action over many years. By no means do these case studies provide a definitive or comprehensive account of ways in which Christian social action can be entrepreneurial. Instead, they illustrate some of the emerging features of a rapidly changing landscape and open up an under-researched field for further enquiry.

Fresh expressions of Church

‘Fresh expressions’ is a term that has entered the vocabulary of the UK Church over the past ten years as a shorthand way of describing attempts to develop fresh and innovative ways of expressing the Christian faith in a changing world. The official ‘Fresh Expressions’ website defines a fresh expression of Church as ‘a form of church for our changing culture, established primarily for the benefit of people who are not yet members of any church’ (Fresh Expressions undated). The vocabulary of fresh expressions can be traced back to the 2004 Church of England report, Mission-Shaped Church (Archbishop’s Council, 2004). This argued that the Church of England’s traditional model of the parish church at the heart of every local community was struggling to engage with large sections of the UK population. While acknowledging that this parochial system remained an essential part of the national Church’s strategy (Archbishop’s Council, 2004: xi), the authors argued that the Church also needed to become open to more innovative approaches and support the development of fresh expressions of Church. Furthermore, they used explicitly entrepreneurial language in setting out this argument and describing the qualities that the Church needs to look for in its future leaders. The report recommended, for example, that ‘those involved in selection [of candidates] need to be adequately equipped to identify and affirm pioneers and mission entrepreneurs” (Archbishop’s Council, 2004: 147).

Mission-Shaped Church proved to be a highly influential report. It led to the establishment of a national ‘Fresh Expressions’ initiative which has gained the official backing of The Church of England, The Church of Scotland, The Methodist Church of Great Britain, The Salvation Army and several other Christian denominations.1 Phrases such as ‘mission entrepreneurship’ and ‘pioneering’ have also entered the vocabulary of many of these denominations as a result (Goodhew et al., 2012: 143-149). It is difficult to quantify the precise number of fresh expressions of Church established over recent years. However, some indication of the movement’s scale and reach is provided by recent survey evidence from Church Army (2013). Across ten English Dioceses (about a quarter of the Church of England), 518 fresh expressions of Church were discovered. With over 20,000 people involved, there was an average of 43.7 people attending each fresh expression (Church Army, 2013: 28). According to the leaders’ estimates, around 40 per cent of the people attending were ‘non-churched’ and a further 35 per cent ‘de-churched’ (Church Army, 2013: 6). The research also uncovered examples of 21 different types of fresh expression of Church (Church Army, 2013: 71). Of these, the category of community development fresh expression appears particularly relevant to the purposes of this paper. This will be discussed in more detail below.

Typically based in deprived urban areas, community development fresh expressions combine social engagement with the development of a new worshipping community or expression of Church (Church Army, 2013: 109). They often involve groups of Christians intentionally relocating to disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods and serving there as neighbours, rather than as volunteers or workers (Thomas, 2012: 243; Wier, 2014: 32-3). Forty-six (nine per cent) of the 518 Anglican fresh expressions of Church uncovered by Church Army’s research were community development fresh expressions (Church Army, 2013: 78). A brief description of one of these, Oaks Skelmersdale, will now be provided, drawing on previously published case study material (Cameron, 2012: 11-12; Dadswell and Ross, 2013: 16-17) and a recent research visit by the author of this paper.

Oaks is a fresh expression of Church based in a refurbished and remodelled council house in a deprived area of Skelmersdale. It was started in 2003 by an Anglican priest, his wife, and three other founding couples. Their vision was ‘to embody an incarnational ministry by living on the estate’ (Cameron, 2012: 11), moving ‘into spaces God creates’ (Dadswell and Ross, 2013: 16). This led them to acquire and redevelop a former council house as a base for mission and outreach. Oak House, as it is now known, has become a ‘community hub’ that is used both for worship and a number of different community activities and groups. The list of activities provided there is not dissimilar from those at any other local Community Centre; they include a foodbank, knitting group, toddler group, and various activities for children and young people. However, a visit to Oaks found that this expression of Christian social involvement looks and feels quite different from many more formalised faith-based social action projects. Their focus was less on the delivery of ‘services’ and ‘projects’. It was more on growing a Christian community.

For the purposes of this paper, two significant features of the Fresh Expressions movement stand out from the preceding account. First, we can observe that the discourse and rhetoric of the Church of England and other denominations is shifting and increasingly incorporating an explicit appeal to the entrepreneurial. Second, it is significant that some of these new expressions of Christian social involvement appear to break the mould of traditional project-based models. These fresh expressions might be said to embody an alternative mode of operation in which the Church is not first and foremost a ‘service provider’ but an ‘intentional community’ (Wier, 2014: 37-38).

‘Growth churches’ and social action

A second feature of a changing landscape concerns new approaches to social action and community engagement being developed by larger evangelical churches and ‘megachurches’. Analysis of UK church attendance over recent decades reveals that although many of the historic mainline denominations are declining overall, some congregations are growing significantly and in some cases exponentially (Goodhew, 2012: 257). The emergence of a small number of UK megachurches, ‘Protestant churches with weekly attendees of 2,000 or more’ (von der Ruhr and Daniels, 2012: 364), is one manifestation of this, particularly within London. Another is the presence within many UK towns and cities of evangelical ‘growth churches’ (Maddox, 2012: 148) – churches which may not be large enough to be a megachurch but are still characterised by an entrepreneurial, growth-oriented vision.

Much of the international literature on megachurches and growth churches has emphasised these churches’ alignment with consumer capitalism (Maddox, 2012; von der Ruhr and Daniels, 2012; Sanders, forthcoming). Maddox, for example argues that businesses and growth churches share many common characteristics: ‘Seized by the vision of growth, they share the entrepreneurial spirit, the hierarchical corporate structures and the marketing techniques of entertainment, conversion and branding. Growth churches are the purest demonstration that… capitalism has become the unassailable global religion’ (Maddox, 2012: 155). Within some accounts, (North American) megachurches are also depicted as ‘non-places’ – transitory sites that lack historical, cultural, or geographic reference points and which leave one with the sense of being nowhere in particular; in this sense, they are said to normalise ‘the banality of consumer capitalism’ (Sanders, forthcoming). However, there is also an emerging body of literature on the social engagement of evangelical and Pentecostal megachurches, both in the United States (Elisha, 2011) and around the world (Miller and Yamamori, 2007).

In spite of such international research interest, the social action of UK growth churches and megachurches has received little academic attention. For this reason, it is significant that a team of researchers from the University of Birmingham has been funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council to conduct a major research project on the social engagement of megachurches in London.2 That research is still being completed but some preliminary findings were presented in a recent conference paper by Dunlop (2014). This provided a case study of Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB), one of the largest UK churches and originator of the internationally renowned ‘Alpha’ course, and drew attention to the two-fold aspirations of HTB’s ambitious vision statement: ‘The Re-evangelisation of the Nations and the Transformation of Society’.

Wier (2013, 2014) provides a further case study of a growth church that will now be considered. “St John’s” is the pseudonym for a large charismatic-evangelical church in a northern English city with around 1,000 regular attendees. This church is based on a campus of former industrial units on the edge of the city centre. From there, it provides a range of ‘vulnerable people’s ministries’ that engage with people who have experienced homelessness, addiction, debt and related issues. Additionally, St John’s provides an extensive array of activities for children, young people and families (these include children’s clubs, detached youthwork, and home visiting programmes). Many of these are delivered in community settings within disadvantaged neighbourhoods around the city. St John’s has also established ‘missional communities’ within many such neighbourhoods. Broadly similar to the ‘fresh expressions of Church’ considered earlier in this paper, these are comprised of church members who have intentionally relocated to a particular locality and are trying to reach out to the local community (Wier, 2013: 46-47).

Three significant features of St John’s social engagement will now be briefly discussed and compared with more traditional forms of faith-based social action. First, St John’s social engagement is citywide in scope, rather than confined to one particular neighbourhood or parish. As such, it appears to be characterised by an entrepreneurial emphasis on expansion into new neighbourhoods that stands in contrast with the more territorially constrained model of the centuries old parish church (Warner, 2010: 154).

A second noteworthy feature of St John’s concerns its level and model of resourcing. The church has a large membership base and teaches the biblical principle of tithing, giving away a tenth of one’s income. With many of its 1,000 or so members giving regularly, St John’s has been able to employ a large staff team (35 people in a range of full-time and part-time roles) to support the church’s community engagement. St John’s members also get involved in a variety of other ways, for example volunteering within community outreach programmes and (in some cases) even moving house to support the church’s mission within particular localities. It appears then that having a large and highly committed membership has been a critical factor in enabling St John’s to engage in social action on a much larger scale than many other congregations are able to. Furthermore, and in contrast to the state-funded forms of faith-based social action often promoted in the New Labour period, large entrepreneurial churches like St John’s appear to be characterised by a significant degree of financial independence from government. This is not to say that they receive no public funding (St John’s had obtained small grants from the Police and local authority) but their ‘core costs’ are often funded by member giving.

A third way in which the social engagement of St John’s appears different from more established forms of faith-based social action concerns the place of evangelism or faith-sharing. As we have seen, previous research often paints a picture of faith-based social action that has very little discernible element of evangelism. At St John’s, in contrast, it appears that ‘spiritual-evangelistic’ and ‘socio-economic’ intentions were subtly intertwined. Focus groups with church leaders and members revealed a strong commitment to active faith sharing while engaged in social action. As one participant put, ‘we’re quite blatant in that we say we do this because we love Jesus – we don’t really try and hide that’ (Wier, 2013: 48).

A national market place of Christian community franchises and brands

The third and final manifestation of a changing landscape examined by this paper concerns the emergence of a national market place of models, franchises and brands that local churches which want to develop a community project can buy into. While the default model of Christian social action in years gone by appears to have been the stand-alone community project, recent years have witnessed a proliferation in the number of entrepreneurial national organisations offering ‘Ready-to-Go’ (Church Urban Fund, 2013) church-based community projects.

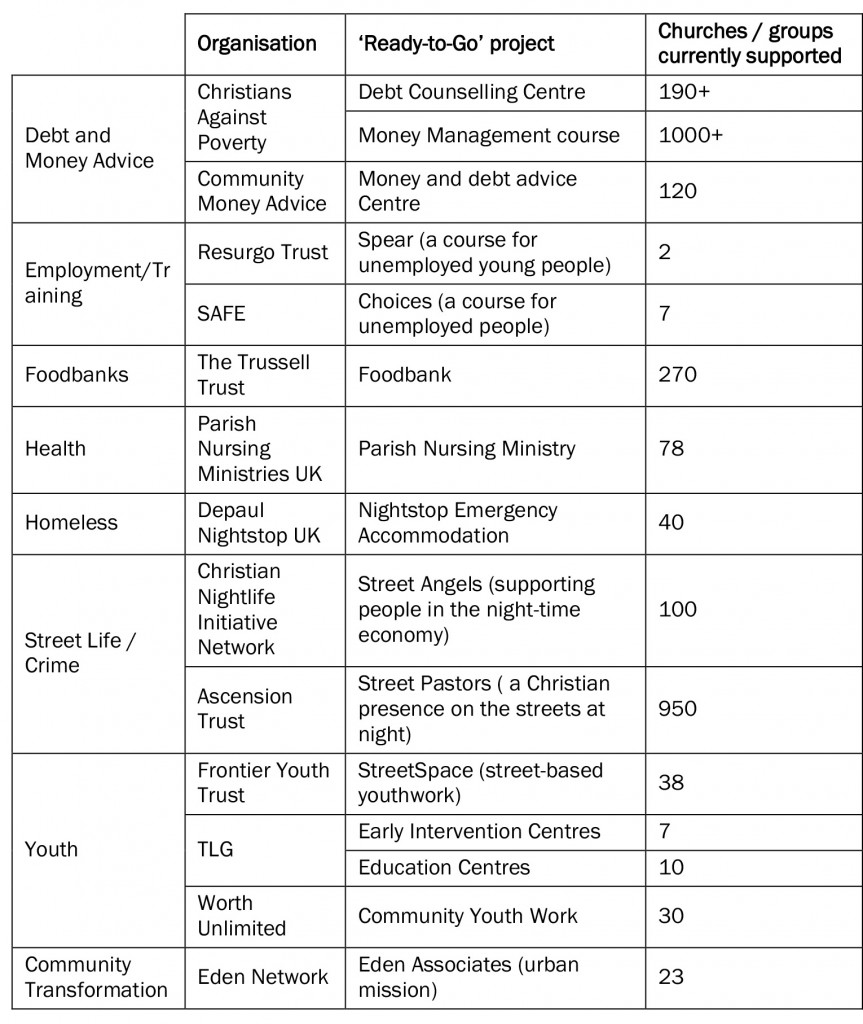

A recent Church Urban Fund report (2013) profiled 13 national Christian organisations which partner with local churches to establish new community initiatives. These organisations are listed in Table 1 below. For local churches, the report argues, there are many advantages in partnering with a national organisation to set up a community project. Such organisations provide a ‘tried and tested’ approach with established procedures, promotional material and governance structures that enable new projects to ‘hit the ground running’ (Church Urban Fund, 2013: 2-3).

Across the 15 ‘Ready-to-Go’ projects summarised above, there is considerable diversity – both in scale and uptake, and in the ways that the host organisations charge for their services. While Christians Against Poverty operate a formal franchise system with a specified annual partnership fee, SAFE use itemised charging, Resurgo employ a joint venture model, and the Trussell Trust request a suggested donation (Church Urban Fund, 2013). What is clear, in spite of this diversity, is that community franchising in the faith sector is developing at rapid speed. The considerable growth in the number of Trussell Trust Food Banks (Lambie-Mumford, 2013) and Christians Against Poverty Debt Counselling Centres (Berelowitz et al., 2013: 47-49) over recent years is one manifestation of this. Another is the continually increasing number of community franchises and brands that local churches can buy into. As we will now go onto see, the work of the Cinnamon Network has been particularly influential in promoting community franchising within the faith sector over the past five years.

According to its website, the Cinnamon Network began at the end of 2010 when (in the context of growing social need, economic cuts, and increasing recognition of the role of voluntary organisations) 50 Christian Chief Executives and leaders were challenged to consider ‘how the Christian community could deliver more local transformation at national scale and to do so at speed’ (Cinnamon Network undated). An approach was developed that involved ‘identifying brilliant church-based community projects and replicating them to national scale by using franchising systems and approaches’. Then, having secured funding from the Cabinet Office’s Social Action Fund and various charitable foundations, the Cinnamon Network began to offer Micro Grants (currently £1500 – £3000 depending on location) to local churches that want to develop a ‘Cinnamon Network Recognised church based community project’ in their neighbourhood. The ‘Choose a Project’ section of the Cinnamon Network website currently lists 25 ‘Cinnamon Network Recognised church based community project[s]’ (Cinnamon Network undated), eight of which also appear on the Church Urban Fund’s list of ‘Ready-to-Go’ church-based community projects.

Developments like these point to the emergence of a national market place of models, franchises and brands that local churches can buy into. This market place appears to becoming increasingly competitive with the number of brands and franchises on offer increasing all the time. Furthermore, ambitious national faith-based organisations with a vision to roll out a particular type of church-based community project into neighbourhoods across the country appear to embody an entrepreneurial ethos. Many of these organisations are non-denominational in character and evangelical in origin, combining a clear theological and moral message with creative adaptation to a rapidly changing social and cultural landscape (Wier, 2013: 83). However, it also needs to be acknowledged that partnering with a national organisation does not necessarily entail becoming a local branch of that organisation. In the majority of cases, local churches continue to have a high degree of ownership of the project (Church Urban Fund, 2013: 3).

These developments also point to an increasingly complex and ambiguous relationship between faith groups and government. On the one hand, entrepreneurial faith-based organisations sometimes promote themselves within the Christian community as an alternative to state-sponsored provision. Matt Bird, founder of the Cinnamon Network, for example, writes: ‘The welfare state as we have known it is history… This is an unprecedented historical opportunity for the Church to step up and step out’ (Bird, undated, 5). On the other hand, it is significant that the Cinnamon Network has been supported with over £1 million Cabinet Office funding (Centre for Social Justice, 2013: 84) and commended by government through a Big Society Award (Prime Minister’s Office, 2013). This may be an indication that, at a time of austerity, new entrepreneurial forms of faith-based social action are quite closely attuned to the kind of charitable activities that the government wants to promote (Kettell, 2012: 282).

Conclusion

This paper has argued that the landscape of UK Christian social action is changing. While much of the discourse about faith-based organisations in the New Labour period focused on their participation in government-sponsored regeneration initiatives, recent years have witnessed the emergence of more entrepreneurial forms of Christian social action. The first case study we considered, the ‘fresh expressions of Church’ movement, provides an example of the way in which the discourse and rhetoric of the Church of England and other denominations is shifting to incorporate an explicit appeal to the entrepreneurial; this is leading to new forms of Christian social involvement that blur conventional boundaries between ‘intentional community’ and ‘service provision’. The growth of social action by large evangelical churches and megachurches provides a second indication of a changing landscape. Fuelled by a strong culture of member giving (which permits a significant degree of financial independence from government), these churches often combine the pursuit of socio-economic objectives with explicitly evangelistic ones. Thirdly, the growing prevalence of Christian community franchises and brands points to the emergence of a national market place for ‘ready-to-go’ church community projects.

Although each of these three examples is quite different, and further research is still needed to investigate them more thoroughly, several cross-cutting themes can be discerned. While much previous faith-based social action has revolved around the Church’s long-standing institutional presence at a neighbourhood level, we are now witnessing the emergence of more entrepreneurial approaches that place greater emphasis on replicability at a larger scale. The changing landscape is also characterised by the emergence of alternative modes of operation and organisational form that expose significant differences as well as similarities between faith-based organisations and other third sector providers. Furthermore, the way in which many entrepreneurial evangelical churches combine social engagement with evangelism seems to challenge some of the prevailing assumptions about faith-based social action that have dominated previous research and policy discourse.

In view of the special focus of this themed issue, some final reflections on the wider implications of the preceding discussion will now be offered. These will reflect firstly on the significance of the word entrepreneurial, before going on to consider some more practical policy implications. Within the context of ongoing debate about the third sector’s relationship with a neo-liberal ‘market-state’ (Bretherton, 2010: 94-95), this paper’s use of the word entrepreneurial raises important questions about whether new entrepreneurial forms of Christian social action are in any way problematic. It may be suggested, for example, that by stepping into address the failings of a shrinking state, entrepreneurial faith groups have become ‘willing or unwilling servants of neo-liberalism’ (Williams, 2012: 173). At this point, it should be stressed that although some Christian denominations and mission agencies have enthusiastically adopted the language of entrepreneurship, others within the Christian community have expressed strong reservations about ‘the embrace of a term soaked in an individualistic version of market capitalism’ (Gay, 2014: 46). It should also be noted that entrepreneurship is a highly elastic term that has been deployed by different commentators in contrasting ways (Volland, 2015: 24). On the one hand, some commentators suggest that entrepreneurial faith groups exhibit a pragmatic preoccupation with growth that makes them reluctant to reflect on issues of subtlety, complexity and nuance (Warner, 2007: 196). This may make them more likely to propose ‘sticking plaster’ (Wier, 2013: 86) solutions to complex socio-economic problems and would appear to lend some support to the charge of being uncritical servants of neo-liberalism. On the other hand, others have suggested that Christian campaigning and lobbying for social reform may be expressions of entrepreneurship (Volland, 2015: 62-64) or that pioneering initiatives which involve living amongst the poor could represent a ‘counter-cultural alternative to market individualism’ (Wier, 2014: 41).

We turn finally to briefly consider the implications of this paper for policy makers and practitioners. As we have seen, public policy interest in faith communities in the New Labour period often focused on state-funded faith-based social action. In contrast, the new and emerging forms of Christian social action described in this paper might be said to be more closely attuned to the newly elected Conservative government’s vision of social action that is largely independent of the state. With continued policies of austerity anticipated over the lifetime of the current parliament, the state-funded element of the third sector looks likely to contract. This will undoubtedly create gaps in local services that entrepreneurial faith-based organisations may attempt to fill. For policy makers and public bodies who are increasingly having to ‘do more with less’, this presents challenges and opportunities. On the one hand, some politicians and policy makers may see entrepreneurial faith groups as untapped repositories of resources or even austerity-proof examples of the ‘Big Society’ in action. On the other hand, the way that these groups operate (departing as they sometimes do from established third sector conventions and norms) may cause suspicion or uneasiness in some public policy circles. In this regard, the conversion-oriented intentions that evangelical faith groups often bring to social action may be a particular source of tension. If they are to negotiate such tensions, public officials will need to become increasingly adept at understanding the complex array of motivations and influences at play within the faith-based social action arena. Rather than instantly applying labels like ‘proselytisation’ to any activity in which there is a hint of faith sharing (Wier, 2014: 41), they may need to pay closer attention to both the content of what is shared and the way that content is shared (Thomas, 2012: 254).

1 See: http://www.freshexpressions.org.uk/about/partners

2 For more details, see the project website: http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/ptr/departments/theologyandreligion/research/projects/megachurches/about.aspx

The author would like to thank this journal’s anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Dr Andy Wier, Church Army’s Research Unit, Wilson Carlile Centre, 50 Cavendish Street, Sheffield S3 7RZ. Email: andy.wier@gmail.com

Archbishop’s Council (2004) Mission-Shaped Church: Church Planting and Fresh Expressions of Church in a Changing Context. London: Church House Publishing.

Berelowitz, D., Richardson, M. and Towner, M. (2013) Realising the Potential of Social Replication. London: International Centre for Social Franchising. http://www.the-icsf.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/1306ICSF-Big-Lottery-v11-LR-single-page.pdf

Bird, M. (undated) Ready Steady Go: How to Start a Church-based Community Project. The Cinnamon Network. http://www.cinnamonnetwork.co.uk/ready-steady-go/

Bretherton, L. (2010) Christianity and Contemporary Politics: The Conditions and Possibilities of Faithful Witness. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. CrossRef link

Buckingham, H. (2012) Capturing diversity: a typology of third sector organisations’ responses to contracting based on empirical evidence from homelessness services. Journal of Social Policy, 41, 3, 569-589. CrossRef link

Cabinet Office (2001) A New Commitment to Neighbourhood Renewal: National Strategy Action Plan. London: H.M. Government.

Cameron, H. (2012) Poverty and Fresh expressions: Emerging Forms of Church in Deprived Communities. London: Church Urban Fund.

Centre for Social Justice (2013) Something’s Got to Give: The State of Britain’s Voluntary and Community Sector. London: Centre for Social Justice.

Chew, C. and Lyon, F. (2012) Innovation and Social Enterprise Activity in Third Sector Organisations: Third Sector Research Centre Working Paper 83. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/generic/tsrc/documents/tsrc/working-papers/working-paper-83.pdf

Church Army’s Research Unit (2013) Church Growth Research Project: Report on Strand 3b – An Analysis of Fresh Expressions of Church and Church Plants Begun in the Period 1992‐2012. http://www.churchgrowthresearch.org.uk/UserFiles/File/Reports/churchgrowthresearch_freshexpressions.pdf

Church Urban Fund (2013) Ready-to-go Church Community projects. http://www.shu.ac.uk/research/cresr/sites/shu.ac.uk/files/programme.pdf

Cinnamon Network (undated) About Us. http://www.cinnamonnetwork.co.uk/about/

Cloke, P., Johnsen, S. and May, J. (2005) Exploring ethos? Discourses of ‘charity’ in the provision of emergency services for homeless people. Environment and Planning A, 37, 3, 385-402. CrossRef link

Cloke, P., Johnsen, S. and May, J. (2007) Ethical citizenship? Volunteers and the ethics of providing services for homeless people. Geoforum, 38, 6, 1089-1101. CrossRef link

Crowe, M., Dayson, C. and Wells, P. (2010) Prospects for the third sector. People, Place and Policy, 4, 1, 29-32. CrossRef link

Dadswell, M. and Ross, C. (2013) Church Growth Research Project: Church Planting. http://www.churchgrowthresearch.org.uk/UserFiles/File/Reports/CGRP_Church_Planting.pdf

Dinham, A. (2012) Faith and Social Capital after the Debt Crisis. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. CrossRef link

Dinham, A. and Lowndes, V. (2009) Faith and the public realm, In: A. Dinham, R. Furbey and V. Lowndes, Faith in the Public Realm: Controversies, Policies and Practices. Bristol: The Policy Press. CrossRef link

Dunlop, S. (2014) The transformation of society and the London megachurch: a case study of HTB. Paper at the ‘Missio Dei – Evangelicalism and the New Politics’ Conference, University of Chester, 12 July 2014.

Elisha, O. (2011) Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social outreach in Evangelical Megachurches. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. CrossRef link

Farnell, R., Furbey, R., Shams Al-Haqq Hills, S., Macey, M. and Smith, G. (2003) ‘Faith’ in Urban Regeneration? Engaging Faith Communities in Urban Regeneration. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Fresh Expressions (undated) What is a Fresh Expression? http://www.freshexpressions.org.uk/about/whatis

Furbey, R., Dinham, A., Farnell, R., Finneron, D. and Wilkinson, G. (2006) Faith as Social Capital: Connecting or Dividing? Bristol: The Policy Press.

Gay, D. (2014) Prospective practitioners: A pioneer’s progress, In: C. Ross and J. Baker, The Pioneer Gift: Explorations in Mission. Norwich: Canterbury Press Norwich.

Goodhew, D. (2012) Church Growth in Britain: 1980 to the Present. Farnham: Ashgate.

Goodhew, D., Roberts, A. and Volland, M. (2012) Fresh: An Introduction to Fresh Expressions of Church and Pioneer Ministry. London: SCM Press.

James, M. (2007) Faith, Cohesion and Community Development: An Evaluation Report from the Faith Communities Capacity Building Fund. London: Community Development Foundation.

Jawad, R. (2012) Religion, social welfare and social policy in the UK: historical, theoretical and policy perspectives. Social Policy and Society, 11, 4, 553–64. CrossRef link

Jochum, V., Pratten, B. and Wilding, K. (2007) Faith and Voluntary Action: An Overview of Current Evidence and Debates. London: National Council for Voluntary Organisations.

Kettell, S. (2012) Thematic review: religion and the Big Society: a match made in heaven? Policy and Politics, 40, 2, 281–96. CrossRef link

Lambie-Mumford, H. (2013) ‘Every town should have one’: emergency food banking in the UK. Journal of Social Policy, 42, 73-89. CrossRef link

Maddox, M. (2012) ‘In the Goofy parking lot’: growth churches as a novel religious form for late capitalism. Social Compass, 59, 2, 146–58. CrossRef link

McCabe, A., Phillimore, J. and Mayblin, L. (2010) ‘Below the Radar’ Activities and Organisations in the Third Sector: A Summary Review of the Literature. Birmingham: Third Sector Research Centre.

Miller, D. and Yamamori, T. (2007) Global Pentecostalism: The New Face of Christian Social Engagement. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Payne, B. (2009) Recent Surveys/Mapping Exercises Undertaken across the English Regions, Scotland, and Wales to Measure the Contribution of Faith groups to Social Action and Culture. http://www.presenceandengagement.org.uk/regional-reports-table-april-2009

Prime Minister’s Office (2013) Churches Network Wins Big Society Award. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/churches-network-wins-big-society-award

Sanders, G. (forthcoming) Religious non-places: corporate megachurches and their contributions to consumer capitalism. Critical Sociology. http://crs.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/07/07/0896920514531605.abstract

Teasdale, S., Buckingham, H. and Rees, J. (2013) Is the third sector being overwhelmed by the state and the market? Third Sector Futures Dialogues, Big Picture Paper 4. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/generic/tsrc/documents/tsrc/reports/futures-dialogues-docs/BPP4-OverwhelmedByStateAndMarket.pdf

Thomas, S. (2012) Convictional communities, In: J. Beaumont and P. Cloke, Faith-based Organisations and Exclusion in European cities. Bristol: Policy Press. CrossRef link

von der Ruhr, M. and Daniels, J.P. (2012) Examining megachurch growth: free riding, fit, and faith. International Journal of Social Economics, 39, 5, 357-72. CrossRef link

Volland, M. (2015) The Minister as Entrepreneur: Leading and Growing the Church in an Age of Rapid Change. London: SPCK.

Warner, R. (2007) York’s evangelicals and charismatics: An emerging free market in voluntarist religious identifies’, In: S. Kim, & P. Kollontai, Community and Identity: Perspectives from Theology and Religious Studies. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Warner, R. (2010) Secularization and its Discontents. London: Continuum.

Wier, A. (2013) Tensions in Charismatic-Evangelical Urban Practice: Towards a Practical Charismatic-Evangelical Urban Social Ethic. DProf Thesis, University of Chester.

Wier, A. (2014) Faith-based social action below the radar: A study of The UK charismatic-evangelical urban church. Voluntary Sector Review, 5, 1, 29-45. CrossRef link

Williams, A. (2012) Moralising the poor? Faith-based organisations, Big Society and contemporary workfare policy, In: J. Beaumont and P. Cloke, Faith-based Organisations and Exclusion in European cities. Bristol: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Yorkshire Churches (2002) Angels and Advocates: Church Social Action in Yorkshire and the Humber. Leeds: Churches Regional Commission for Yorkshire and the Humber.