Abstract

This paper examines the phenomenon of “property guardianship” in England, focusing on property guardians’ entry into this precarious sector and the reality of their occupation. Drawing on data from a survey of 217 London-based property guardians and an analysis of 512 online property guardian advertisements, we examine: (i) how property guardian advertisements construct this form of accommodation as a destination for young people unable to afford private rented accommodation, and (ii) whether this image meets the reality of day-to-day occupation in the sector. We argue that these advertisements reveal tensions between the presentation of this form of accommodation – billed as a solution to the precarity caused by the lack of housing affordability for young renters – and the precariousness experienced by those living in the sector.

Introduction

The series Crashing –Phoebe Walter-Bridge’s Channel 4 sitcom released in 2016 – depicts the life of six “property guardians” living in a disused hospital in London. Each in their twenties, they live in the building to protect it, receiving lower “rent” in exchange for life with stricter rules in a “quirky” home. When asked if they enjoy living under the scheme, one character responds, wryly: “You’re not allowed to have parties, cook meals, light candles, have sex, express emotion, claim any rights, argue if they want to throw you out with only two days’ notice, or smoke. It’s a riot” (Big Talk Productions, 2016). This image of a homogenous group of “carefree, young people”, likely “university-educated” (Ferreri et al., 2017) is the face of this “property guardianship” phenomenon. The proposition is win-win: building owners with empty properties save on security costs and a host of other expenses; and the guardians live in the property for a lower cost than elsewhere in the private rented sector.

This paper interrogates the property guardianship phenomenon by drawing on two sets of data: a survey of 217 London-based property guardians and an analysis of 512 online property guardian advertisements. We examine: (i) how property guardian advertisements construct this form of accommodation as a destination for young people unable to afford private rented accommodation, and (ii) whether this image meets the reality of day-to-day occupation in the sector. We argue that these advertisements reveal tensions between the presentation of this form of accommodation – billed as a solution to the precarity caused by the lack of housing affordability for young renters – and the precariousness experienced by those living in the sector.

The analysis is in four sections. The first provides an overview of what property guardianship is and what is known about its extent and operation in the UK. Drawing in part on Clapham’s work on categorical identity (Clapham, 2005), we then to turn to three issues: (i) construction of property guardianship (how does the sector seek to establish itself as something distinct from the private rented sector?), (ii) entry into and churn within the sector (how do property guardians become involved and how long do they stay in such accommodation?), and (iii) the reality of life within the sector (does living as a property guardian match the image constructed of it?).

Within this analysis, there are two cross-cutting tensions that we seek to explore. First, the private rented market’s autogenic solution to the problem of precariousness is to generate even more precious forms of housing, despite the sector’s status as an already “highly precarious living situation” (McKee et al., 2019). For tenants unable to access the relative security of home ownership and/or unable to afford market rents, the market provides even more insecure accommodation at a lower cost: the offer is that to get to a position of security, they must endure insecurity. As Reeves-Lewis argues, a new breed of “rogue landlords” operate by issuing properties for occupation on licences as opposed to via tenancies (Reeves-Lewis, 2018: 19). Rugg and Rhodes highlight practices in the “shadow” private rented sector – such as a failure to protect deposits or maintain properties – to which tenants at the “very bottom end” of the market are most likely to be hit (Rugg and Rhodes, 2018: 18-19). Here, the private rented sector is responding by offering a trade-off – in practice, a Hobson’s choice – between affordability and the security of occupation.

Second, much has been written about the processes of buying a home. The role of estate agents, the “dialogue of aspiration” they employ, and the priorities and decision-making of home-buyers, have all been subject to detailed scrutiny (Pryce and Oates, 2008: 320). However, notwithstanding the greater pressures of time, supply and churn, very little work has been done on the same processes for tenants renting privately. As McKee et al underscore, “housing preferences are not created in a vacuum”: they are shaped by “broader structural forces” (McKee et al., 2017: 326, 331). We would argue that these preferences and decisions are also shaped by granular, day-to-day processes and – in particular – property searches online. How different offerings within the PRS characterise themselves to prospective occupiers tells us about both how sub-sectors seek to characterise themselves or distinguish between one another and demonstrates how they employ many of the same processes in the “dialogue of aspiration” that have been analysed under home ownership.

Methods

The analysis that follows draws on two strands of empirical work: (i) a survey of 217 London-based property guardians and (ii) an analysis of 512 online property guardian room listings.

On the former, the survey was completed in course of our work to support the London Assembly Housing Committee’s inquiry into the phenomenon in September to November 2017 (London Assembly, 2018). We advertised for participants (i) through a Facebook campaign across September to October 2017, followed by a shorter YouTube campaign in November 2017 and (ii) via property guardian firms emailing the survey link, using contact text agreed with the research team. The survey asked a series of closed questions, mirroring some English Housing Survey descriptors and questions about demographics, and a series of more open questions assessing entry into the sector, their experiences as a property guardian, and the raising of complaints or redress procedures. A total of 217 responses were included in the analysis for this paper.

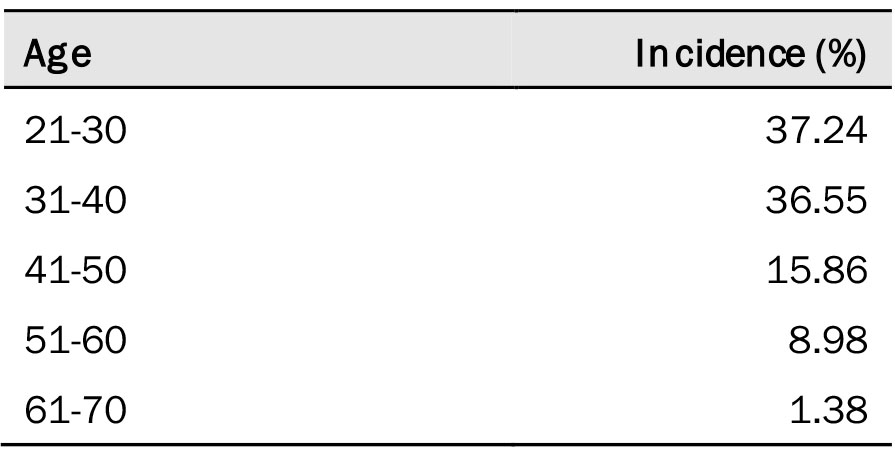

In terms of demographic descriptors, within the sample, male respondents were marginally overrepresented, forming 55 per cent of participants, with women comprising 42 per cent. Very few identified themselves as having a health problem or disability that limits their day-to-day activities: only four per cent of participants. Compared to the private rented sector more generally, the age distribution in the sample suggests that property guardians are generally younger than their counterparts renting properties, but not by a large margin. Within the private rented sector, the mean age of a renter is 40 – as opposed to 36 in this sample – and 67 per cent are aged under 45 – as opposed to 78 per cent in this sample (English Housing Survey, 2016).

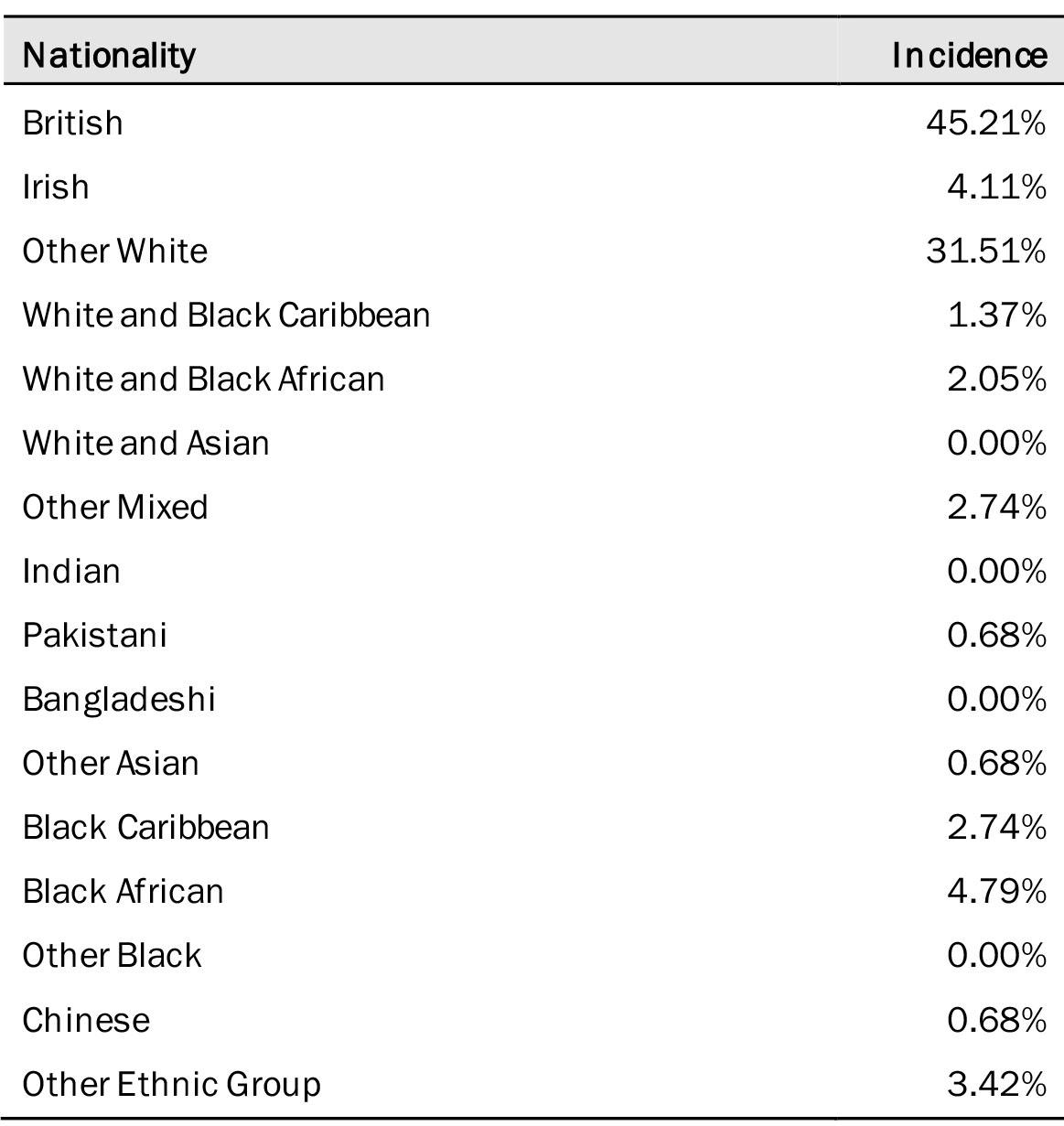

There were a wide range of ethnic groups represented within the sample, as reflected in Table 2. The majority were British, Irish, or from another white background (81 per cent).

The survey data, therefore, appears to offer some diversity across key demographic indicators. Although the analysis that follows does not rely on its representativeness of the property guardianship sector as a whole, more detailed analysis of this elsewhere indicates that these descriptors – particularly the low incidence of those with disabilities and the male skew – characterise the London-based property guardianship sector (Hunter and Meers, 2018b).

On the second strand, to create the sample, all URLs for posts on SpareRoom.co.uk which used the phrase “property guardian” or variants thereof (e.g. “property guardianship”) on the 1st July 2018 were pulled into a spreadsheet using a macro. This provided a starting sample of 729 links. Duplicate posts and those which did not point to a property advert were then removed manually, leaving a final sample of 503 adverts. These adverts were then trawled manually by a group of (paid) students at York Law School with reference to a data entry form. This form captured key descriptors – such as rent, the type of property, how many bedrooms, and so on – and any references to property guardianship or elements of the licence agreement within the advert text.

An overview of property guardianship

Property guardianship companies bill their offering as a straightforward proposition where all parties benefit: owners of otherwise empty properties (residential or ex-commercial) secure them by contracting with a company who subsequently grant a licence to “property guardians” to live in the building. The property owner is able to secure their property without recourse to costly security services or other charges associated with empty properties (such as increased council tax or – if the property is unoccupied for longer than three months – business rates). The guardians themselves can live in cheap(er) accommodation when compared to the private rented sector at large, or can afford to live in more central locations in large cities – particularly London – which may otherwise be unattainable. The business model functions through the property guardian company itself receiving license fees from the guardians and, especially if works are required to make the building habitable, a fee from the owner of the building too. In some cases, the building owner may also receive a share of the property guardian’s licence fees.

The practice has its roots in the Netherlands, where the phenomenon is known as “antikraak” (translating to “anti-squat”). Having emerged as a “Dutch invention” in the 1980s, it ballooned following the criminalisation of squatting in 2010 (Buchholz, 2016: 93). The sector there is now burgeoning, with approximately 50,000 guardians in total, generally clustered in large cities. As Huisman argues, this growth is the result of a gradual shift within the PRS “towards the Anglo-Saxon model of weaker tenant rights, without this being an explicit policy goal” (Huisman, 2016: 102). It currently occupies a space as a sizable but residualised sub-sector of the private renting, despite efforts to mark itself out as a differential form of occupation. As Buchholz notes, “antikraask” is “a rental phenomenon that refuses to be recognised as rent” (Buchholz, 2016: 93).

Little is known about property guardian practices in the UK, but it is a more recent phenomenon imported by Dutch antikraat companies entering the UK market, particularly in London. The number of studies into property guardianship are still very limited and there are significant gaps in our understanding of the sector (for an insight into the existing literature, see Ferreri and Dawson, 2018; Hunter and Meers, 2018a). Previous research into Property Guardianship in London, does however provide some context on extent, demographics and entry into the sector (Hunter and Meers, 2018b).

First, although there are no definitive figures given the large number of small operators in the sector, the largest providers in the industry estimate that there are up to approximately 7,000 individuals living as guardians in the UK (London Assembly Housing Committee, 2018: 11). Most of these are in London, with the others in larger cities (chiefly Bristol, but also Manchester and Brighton). The sector appears to be growing, both in terms of its geographical reach across the UK, the number of property guardian companies, and total numbers living as Guardians. Ferreri et al. underscore that new companies are entering the market continuously, contributing to its status as a “growing sector” (Ferreri et al., 2016: 250). The London Assembly’s housing committee points to the capacity for significant total growth in the UK, suggesting that the phenomenon could yet approach the far higher numbers living as guardians – as outlined above, approximately 50,000 people – in the Netherlands (London Assembly Housing Committee, 2018: 11).

In terms of the demographics of the sector, the composition of property guardianship has offered suffered a similar fate to ‘generation rent’, being characterised as a relatively homogenous group. The stereotypical image of property guardian is a British or EU national in their mid-20s to mid-40s, working part-time or in University-level education (Ferreri et al., 2017: 250). Research suggests, however, that much like “generation rent”, property guardians are far more demographically diverse, with variation among age, income, ethnicity and employment status (Hunter and Meers, 2018b). Ages in our survey sample ranged from 22-66, with a mean of 36. As outlined in Table One above, compared to the Private Rented Sector more generally, the age distribution in the sample suggests that property guardians are generally younger than their counterparts renting properties, but not by a large margin.

In terms of what is known about entry into and churn within the sector, our previous research indicates that most had come to their current property from the private rented sector (45 per cent), or from another property guardian property (33 per cent). This indicates that these properties are occupied by those who would otherwise be renting elsewhere in the private rented sector, and underscores the high levels of internal churn between property guardian properties (Hunter and Meers, 2018b: 20). Of those moving into the sector 41 per cent did so “voluntarily” – namely, they left their previous accommodation of their own accord, without being forced to do so (such as by reason of a rent increase, a tenancy ending, etc) (ibid, 21). Guardians underscored the importance of “word-of-mouth” (61 per cent) to their entry into the sector, with a significant number (30 per cent) having learnt about the phenomenon from the internet and online property searches (e.g. for “room to rent London” or “cheap rent London” etc) (ibid, 50).

Construction: The “categorical identify” of property guardianship

At the core of our analysis is how the image of “property guardianship” – reflected by the text and images on property listings, the companies’ websites, and social media advertisements – presents the sector to would-be guardians and whether this is the reality of occupation within it. This is of more than theoretical interest. As we have argued elsewhere, the construction of the legal relationship between guardians and guardian companies (including how this relationship is presented on the relevant company’s website) can be of significance in determining whether residents are occupying on a lease (i.e. via a tenancy) or a licence (Meers, 2019). Our focus here, however, is more broadly on how “Property Guardianship” companies construct occupation of their properties as something distinct from “private renting”; an “exciting alternative” to finding accommodation in the private rented sector, rather than what Rugg and Rhodes might describe as the “shadow private rented sector” (Rugg and Rhodes, 2018: 18-19).

Clapham’s work on bringing the scholarship of “categorical identity” to the analysis of housing tenure is valuable here. He argues, drawing on King, Taylor, Craib and others, that identity is formed through both acts of differentiation from others, and by identification of similarities with others. Categorical identity is about the labels society and individuals use to ascribe these similarities and differences, of which housing tenure is a potent example (Clapham, 2005: 14). Categories bring with them discourses and socially constructed forms of meaning, and are maintained by a “recognition of difference” from other categories (ibid, 15). To put it another way, the insight of this work on identity is that “housing is seen as a means to an end rather than an end in itself” (ibid, 17). The tenure in which one lives serves more than just its housing function.

The label “property guardianship” to describe a phenomenon distinct from the private rented sector is an exercise in categorical identity par excellence. As these companies offer rooms for the a payment of a monthly “fee”, listed alongside tenancies and subject to many of the same controls, property guardianship can at best be characterised as a sub-sector of the private rented sector, albeit under a far more insecure form of occupation than under a tenancy. However, the private rented sector carries with it certain discourses that have emerged in previous research: pracarity, a lack of “choice”, or as “money down the drain” (See McKee and Mihaela Soaita, 2018; Hoolachan et al., 2017: 71). In their property listings and promotional materials, Property guardian companies actively distinguish themselves from these discourses. In our advert sample, listings refer continually to not just the potential savings (“ideal if you’re looking to save for your first home”) but also the broader societal contribution that property guardianship makes:

“VPS Guardian Services are pleased to offer rooms in a former Children’s home. The property is in an excellent condition throughout. If you’re wondering why such a low price? When you’re a property guardian, you are helping us and the owner by keeping the property occupied, and this is our way of saying thank you! All we ask is that you keep the properties in good condition! It’s much cheaper than private renting, ideal if you’re looking to save for your first home, or just looking to save money.” (Excerpt from SpareRoom.co.uk Property Listing).

This is the trade-off implied for occupation as a property guardian: a lower rent – either out of necessity or to help satisfy your future housing aspirations – but with greater expectations in comparison to the private rented sector. This is, as the company Ad-Hoc put it, the “small price to pay”:

“As an ADHOC Property Guardian, you get accommodation at the faction of the usual cost and in return our clients get peace of mind you are there keeping an eye on their property. All we ask is that your accommodation is kept clean, tidy and presentable. We believe this is a small price to pay for accommodation that is spacious, unique and remarkably inexpensive.” (Excerpt from SpareRoom.co.uk Property Listing).

The rhetoric of lifestyle so often employed in advertisements directed at home-owners (see Pryce and Oates, 2008) abounds in the advert sample, but directed at prospective licensees. As property guardian companies solicit empty properties to secure, many of these were not built for residential use. These are billed as “quirky” and “trendy”. The insecure licensing arrangements are presented as “flexible”. In a similar way to what Lancione describes as the “double-faced nature of precarity, as both product and producer of urban life”, here the effects of precarity are presented as part of a beneficial urban lifestyle (Lancione, 2019: 182):

“This property is a disused pub with all of the quirky features and character of a Old English Inn.” (Excerpt from SpareRoom.co.uk Property Listing).

“This Large Farmhouse has lots of character and is offered as part of the Property Guardian scheme – in need of protection, we are looking for responsible professional individuals that are looking for something “Quirky and Flexible” to keep the building in use.” (Excerpt from SpareRoom.co.uk Property Listing).

This practice of differentiating property guardianship from the private rented sector is accompanied by the “elements of similarity” that form part of a categorical identity (Clapham, 2002: 15). Adverts present property guardianship as not only an attractive form of accommodation, but also as a lifestyle choice. Prospective guardians can live with “like-minded” and inspirational individuals:

“So if you’re looking to be part of a community of like-minded, responsible professionals, where your environment is smoke, pet and children free, then this could be ideal for you.” (Excerpt from SpareRoom.co.uk Property Listing).

“Occupy large living spaces in this delightful town, as a cheaper alternative to renting privately. Create your ideal community moments from green spaces, town amenities and inspirational people at the University for Creative Arts.” (Excerpt from SpareRoom.co.uk Property Listing).

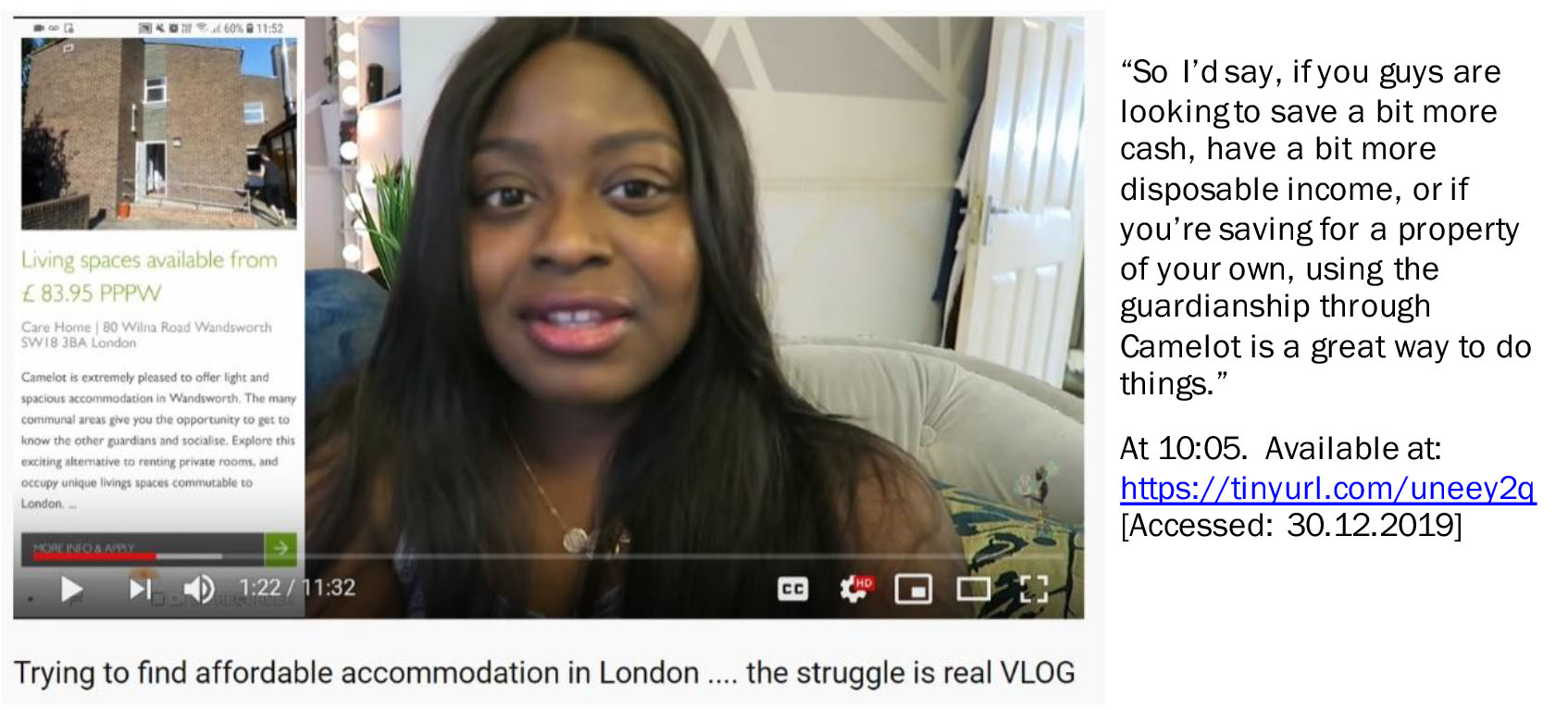

The practices of distinguishing property guardianship from other forms of occupation and using allusions to lifestyle are found not just in the property listings themselves, but also on the Property Guardian companies’ advertisements on social media and on their own websites. These companies have an active online presence, posting on social networking websites, particularly Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Youtube. These include sponsored video blogs on Youtube, where the vlogger advises the viewers:

Figure 1: Thumbnail picture and quote from Youtube promotional video for Camelot Property Guardians.

Source: Available at: https://tinyurl.com/rctx8r7 [Accessed: 30/12/2019]

These adverts for prospective occupiers, found on the same online platforms advertising private rented accommodation, construct this “categorical identity” of the “property guardian” as something distinct from the private rented sector. Property guardianship is not part of the “shadow private rented sector” (Rugg and Rhodes, 2018: 18-19), but is an exciting alternative: a “flexible” and “quirky” form of occupation in its own right. The frequent references to the ability to “save for a deposit” or “have a bit more deposable income” tap into deficiencies in the unaffordability of the private rented sector and present property guardianship as a solution.

Entry: How and why do prospective occupiers become property guardians?

Having considered how property guardian companies construct this form of accommodation, we now consider how prospective occupiers become property guardians and the churn within the sector. How property guardians enter and the extent to which they remain in property guardianship is important for two reasons. First, data on entry and churn can help to interrogate the property guardian companies’ characterisation of this form of occupation as an alternative to private renting. A guardian’s previous accommodation can help to illustrate whether these households are coming from the private rented sector or elsewhere, and the extent of churn can help to interrogate how long guardians are able or willing to remain in this form of inherently precarious accommodation, either remaining in single properties or moving from one property guardian property to another.

Second, the means of finding accommodation has evolved dramatically over the last decade. The proliferation of online property listings – such as RightMove.co.uk and SpareRoom.co.uk – means that the monopoly of the lettings agents’ window has long since elapsed. How guardians came to know about the sector and specific properties is important to assess both their understanding of what guardianship is, and features of modern property searching.

Our survey data reveals that most guardians were previously occupying a property under a tenancy elsewhere in the private rented sector (45.39 pe cent). The second largest proportion were comprised of those from another property guardian property (33 per cent). A substantial percentage did not have any settled accommodation in their or their spouse’s name (17.73 per cent) and very few came from home ownership (1.4 per cent). Once in a property guardianship scheme, most remained in a property for just over a year (an average of 12.6 months), with the longest period of occupation extending to six years.

Reasons for leaving their previous accommodation were wide-ranging, with most focused on property size (10 per cent wanting somewhere larger) and cost (with 17 per cent moving to find somewhere cheaper). Open comments within the survey illustrate that new guardians entering the sector did not necessarily do so out of great enthusiasm, but instead due to the difficulties renting elsewhere in the private rented sector presented:

“We were not in a position to save enough to raise the astronomical deposit, administration and handling fees needed to rent privately again. We turned to property guardianship in the absence of any other options and weren’t “attracted” to the potential pay lower rent, it was a necessity. We have moved house 6 times in the 7 years we have been in London.” (Female, 35 years old).

Another guardian contrasts their impression of these schemes as something insecure, with their experiences of great insecurity in the rest of the private rented sector:

“I heard about it 10 years ago but thought that standard rentals would be more reliable and safe, but in fact, have had to move +12 times in 10 years, living with all kinds of strangers – some great / some terrifying. I finally needed space and wasn’t prepared to share with any more nutter randoms, so decided to go this route. Saving a lot of money, but definitely not a desirable location. Will move as soon as I can find something better.” (Female, 40 years old).

Others had simply stumbled into property guardianships, either by searching online for cheap places to live, from a room being listed alongside other private rentals on websites intended for the private rented sector at large (such as SpareRoom.co.uk), or from advertisements by property guardian companies:

“I saw a news report on TV several years ago and consequently searched online “lower rent”, was the main reason.”

“I saw a [PG company] property on Spareroom, which was local to where I was living and much cheaper than the other properties available.” (Male, 24 years old)

“I was stocking a freezer with ben and jerry’s ice cream and noticed a promotion with DotDotDot on the package. Funny how things happen like that.” (Male, 22 years old)

This led to concerns from guardians that many of peers – or themselves – were insufficiently aware at their point of entry of what occupation as a guardian truly entailed, particularly the significance of their purported legal status as licensees as opposed to tenants:

“I do think that guardians are woefully unaware of their rights. Guardian companies (including my own) are reticent on the actual legal rights of property guardians (they are, as cases are beginning to prove, and as lawyers and the housing act insist, tenants like any other tenancy arrangement).” (Male, 30 years old)

The survey responses on entry and churn demonstrate three things. First, that the sector caters for those who would otherwise be living elsewhere in the private rented sector, with the vast majority of outside entrants coming from a private rented property. Second, entry into the sector was mostly as a result of happenstance, either coming across advertisements when searching for private rented accommodation or from learning of schemes from friends. As a result, it was not always accompanied with a full understanding of the rights and responsibilities of guardianship, but instead only an insight into the “categorical identity” presented within the advertisements. Finally, the data points to a significant internal churn within the sector, highlighting that guardians can and do move between different property guardian premises.

Reality: Does the experience match the construction?

Having considered the construction of and entry into the sector, this section assesses the reality of occupation as a property guardian. Three key issues are dealt with here. In response to our survey, two particular concerns were repeatedly identified by property guardians: conditions tied to their occupation and deposits. Both of these are functions of how property guardian companies issue licenses for occupation of properties as opposed to tenancies and each will be dealt with in turn. The third issue is the broader assessment of categorical identity and how this is reflected in the survey responses.

The license agreement

As outlined above, property guardian companies almost always seek to provide accommodation through the means of a license agreement as opposed to a tenancy. The former is less secure and carries fewer protections (for instance, the requirement to protect deposits). Whether guardians are in fact occupying as licencees is not always clear cut and depends on the extent of their “exclusive occupation” of the property, but our purposes, the reality of occupying occupation on a (purported) licence can bring with it far greater controls and intervention over the use of the property.

When asked about the terms of their occupation, guardians in our sample detailed a series of exhaustive rules about their use of the property. Some of these are arguably tied to the function of a guardian to “secure” the property through their occupation, such as authorising absences or limiting visitor numbers. Others may be focused on the preservation of the agreement’s legal status as a licence as opposed to a tenancy, such as detailing inspections without notice:

“Licence agreement is a joke! did you know we’re not allowed to invite more than 2 people and they’re not allowed to spend a night here? they also come in for inspection without any prior notice even when we’re not at home. we’re also meant ask them for a permission (!!) when we want to go on holidays for more than 2 nights!” (Female, 25 years old).

The prohibition of children from entering the property is almost ubiquitous condition imposed by property guardian companies. Other limitations on visitors – such as length of stay or being unaccompanied – were highlighted by guardians in our sample:

“Lots of rules to follow: – no children allowed in the flat – no more than two guests at a time – guest cannot stay more than 3 nights without permission – guests cannot be left alone in the flat – no use of candles, incense or any naked flames – gas hobs not allowed and only small electric hobs allowed – they can enter the property without previous notice for inspections or repairs/checks.” (Female, 46 years old).

This environment of control and oversight is accompanied by short notice periods and a lack of certainty over the length of occupation. Of those guardians surveyed who were aware of the notice period in their licence agreement, 90.4 per cent had a notice period of at least 28 days, with 87.7 per cent having a notice period of either four weeks, 28 days, or 30 days. 9.6 per cent of the sample detailed a notice period of less than four weeks: seven per cent of two weeks, and two per cent of one week (an unlawful period pursuant to the Protection from Eviction Act 1977). Of those in our survey who had entered their current accommodation from another previous property guardian property, 19 per cent were given less than two weeks’ notice of the move by the property guardian company.

In light of these controls and the insecurity of occupation, we would argue that the prohibition of children from these properties is a tacit recognition that the precarious environment is unlikely to be appropriate. Drawing on Ferreri and Dawson’s work on “self-precarization” in property guardianship (2018), these companies may recognise that there is a trade-off – or in the advert detailed above, a “price worth paying” – for some adults who wish (or face little option) to accept insecure accommodation as a guardian. To not extend this self-precarization dilemma to households with children is to recognise its damaging potential.

Lack of deposit protection

A key difference between occupying a property on a licence as opposed to a tenancy is that deposits are not required to be protected. For assured shorthold tenancies, landlords are required to hold deposits in accordance with an authorised deposit protection scheme under s.212 Housing Act 2004. For guardians on licence however, no such controls apply. As a result, property guardian companies do not need to ring-fence deposit money, make provisions for its safe retention in the event of insolvency, provide a mechanism for resolving disputes, or return the money in any specific timeframe. Guardians are only protected by the bounds of private law.

This issue is particularly acute as guardians pay large deposits or deposit-like fees. Only seven per cent of our sample paid no deposit at all, with an average payment of £565. Of those that did pay a deposit, only six per cent of guardians paid less than their monthly licence fee. These are substantial down payments on often unfurnished properties with very limited facilities. Problems with the management and returns of deposits were raised by guardians in the sample:

“I did pay a deposit which was equivalent to one month’s rent. When I left and handed the keys back, I was told I was going to receive my deposit back within a week. I did not. I had to chase this over emails and phone calls for over 3 months. Every time I spoke to them, they said I was going to get the deposit back soon. At the end I had to tell them that I would take legal action if I did not get this within a week. After that conversation, I did receive my deposit back.” (Female, 41 years old)

In our survey, a small number of guardians explicitly suggested that their deposits should be protected as they are elsewhere in the private rented sector:

“Deposits should be protected in a deposit scheme and guardianships do not use deposit protection schemes, which is ridiculous. My deposit with another guardianship was not returned until a year later only after taking the company to a small claims court – a time consuming and stressful experience.” (Non-disclosed gender, 24 years old)

Given the large sums of money involved and the internal churn within the sector, where deposits may be rolled forward through various properties, problems attaining owed deposit monies or anxieties about the adequacy of their protection were a widely shared experience of guardians in the survey.

Categorical identity and property guardianship

Within the survey data, there was evidence of the Janus-face of “categorical identity” identified by Clapham (2002, 15-17): evidence of both elements of differentiation between property guardianship and the private rented sector at large; and identification of similarities with others living in the same arrangement.

Guardians raised the “price to pay” proposition so often seen within the advertisement sample – cheaper rent than elsewhere in the private rented sector at the cost of insecurity and rights – as a reason for wanting to continue to live in a property guardian scheme:

“Despite the endless problems guardianships throw at you (lack of tenants rights, no deposit protection scheme, poor maintenance) the cheap rent is the reason I am still in a scheme. I also really enjoy living in interesting spaces and living with people from a variety of backgrounds and nationalities.” (Non-disclosed gender, 24 years old)

Guardians compared property guardianship against other forms of private renting. The precariousness of the property guardianship schemes was characterised against the already precarious and expensive private rented sector, particularly in London:

“I don’t mind the instability; I prefer it over the exorbitance of private rent, the avarice of agents, and the scandal of agency fees, and the general swollen, disgusting state of the London housing market.” (Male, 30 years old)

Others raised elements of similarity within their experiences. Especially the benefits of living with like-minded people and sharing the experience of property guardianship as part of community. This echoes previous research by Heath and Kenyon on the “flexible living arrangements” that about in shared accommodation in the PRS (2001, 86). Guardians underscored some of the benefits of living with others in such a flexible arrangement:

“For the first time in London I’m part of a little community, we have dinner together, we talk about how to recycle rubbish, we organise the cleaning of the house together, we CHAT. It’s really nice to be part of a building where I live with like 20 other people. I know that if I need anything someone will be there.” (Female, 26 years old)

However, property guardians were far from universally positive about the sector’s existence or its differentiation from the private rented sector. One participant referred in particular to their intention to move to a “normal tenancy” at some point in the future. Increases to the license fees charged by property guardian companies had shifted the balance on the “price to pay” too far:

“I will look for a normal tenancy. The guardian companies are becoming too greedy, it’s not worth it any more. They just want to get more money and give nothing in exchange. There is no point to pay almost £500 for a horror looking room with rats visiting me at night, pay all the extra bills, and not even getting a £1 lock installed on my bedroom door.” (Male, 37 years old)

Others highlighted that this “price to pay” was a fallacious choice. It was out of the lack of affordability elsewhere in the private rented sector that made their current housing circumstances an inevitably: they were not living as a property guardian out of choice:

“I cannot afford to live anywhere else. London prices are impossible and I feel trapped in this situation with [the property guardian company].” (Male, 28 years old)

These responses demonstrate that those features of carving out a separate categorical identity for property guardianship – contrasting features of the private rented sector against property guardianship, ascribing a sense of identity to a likeminded community of individuals and so on – were present within the sample. Most prominent was the “price to pay” narrative: with some guardians content to sacrifice security or conditions for lower rent. For others, this “price” had become too high, or the choice was a fallacy, they had little other affordable accommodation available within London.

Conclusion

Having provided an analysis of the property guardianship phenomenon rooted in our survey and advertisement data, we can return to our two tensions we outlined at the start. First, here, the market has sought to solve problems of precariousness within the private rented sector, by generating an even more precarious form of accommodation. As in the construction of property guardianship in the advertisements and the “price to pay” narrative in these listings and from some of the guardians themselves, property guardianship companies have presented the schemes as an alternative to private renting and as reflecting a particular lifestyle.

Although for some guardians in the survey, their time as a property guardian has been a positive experience, the reality of the occupation – and the problems caused from the use of the licence, the lack of protections on deposits, and the environment in many of these properties – are more akin to the “shadow private rented sector” highlighted by Rugg and Rhodes (2018: 18-19). As one participant in the survey put it:

“The fact that property guardianship exists at all is a symptom of a broken housing market. We are, essentially, twenty-first century squatters. For a government to ban squatting in empty residential property is a moral outrage…Property guardianship is here to stay and will only grow in coming years.” (Male, 30 years old).

Second, although the routes into homeownership are well analysed, far less is known about how people search for and apply for private rented accommodation. We argue that these practices require much greater interrogation. How forms of accommodation in the private rented sector are constructed for prospective occupiers can shape their understanding of the terms of their subsequent occupation. Those online platforms – such as SpareRoom.co.uk and RightMove – are hugely significant actors in the operation of the private rented sector and these listings demand greater scrutiny.

Although our findings deal with property guardianship in England specially (and in terms of our survey data, London exclusively), our findings have relevance outside of the immediate substantive focus of the paper. Drawing on Clapham’s work on categorical identity helps to interrogate the labels that sub-sectors within the private rented sector use to describe themselves: be it “property guardianship”, or others, be it “professional let” or “student accommodation”. Analysing how sub-sectors within the private rented sector seek to differentiate themselves from other sectors, and drawing similarities within the sub-sector itself, can help to interrogate how (particularly online) advertisements impact on entry and churn in the private rented sector and whether the reality of occupation within these sub-sectors reflects this construction.

Caroline Hunter, York Law School, University of York, Law and Management Building, Freboys Lane, YO10 5GD. Email: caroline.hunter@york.ac.uk

Big Talk Productions (2016) George Kane [Director], ‘Crashing’ [Television broadcast] (Channel 4).

Buchholz, T. (2016) Struggling for recognition and affordable housing in Amsterdam and Hamburg: resignation, resistance, relocation. PhD Thesis: University of Groningen.

Clapham, D. (2005) The Meaning of Housing: A Pathways Approach. Bristol: Policy Press. CrossRef link

English Housing Survey (2016) Private Rented Sector report for 2015-16. Department for Communities and Local Government.

Ferreri, M., Dawson, G. and Vasudevan, A. (2017) Living precariously: Property guardianship and the flexible city. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42, 2, 246-259. CrossRef link

Ferreri, M. and Dawson, G. (2018) Self-precarization and the spatial imaginaries of property guardianship. Cultural Geographies, 25, 3, 425-440. CrossRef link

Heath, S. and Kenyon, L. (2001) Single Young Professionals and Shared Household Living. Journal of Youth Studies, 4, 1, 83-100. CrossRef link

Hoolachan, J., McKee, K., Moore, T. and Mihaela Soaita, A. (2017) ‘Generation rent’ and the ability to ‘settle down’: economic and geographical variation in young people’s housing transitions. Journal of Youth Studies, 20, 1, 63-78. CrossRef link

Huisman, C. (2016) A silent shift? The precarisation of the Dutch rental housing market. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 31, 93-106. CrossRef link

Hunter, C. and Meers, J. (2018a) The ‘Affordable Alternative to Renting’: Property Guardians and Legal Dimensions of Housing Precariousness. In: Carr, H, Edgeworth, B, and Hunter, C. (eds) Law and the Precarious Home: Socio-Legal Perspectives on the Home in Insecure Times. Oxford: Hart: 65-86.

Hunter, C. and Meers, J. (2018b) Property Guardianship in London: A report produced on behalf of the London Assembly.

Lancione, M. (2019) The politics of embodied urban precarity: Roma people and the fight for housing in Bucharest, Romania. Geoforum, 101, 182-191. CrossRef link

London Assembly Housing Committee (2018) Protecting London’s property guardians. London Assembly.

Mckee, K., Moore, T., Soaita, A. and Crawford, J. (2017) ‘Generation Rent’ and the Fallacy of Choice. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41, 2, 318-333. CrossRef link

McKee, K. and Mihaela Soaita, A. (2018) The ‘frustrated’ housing aspirations of generation rent. UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence.

McKee, K., Mihaela Soaita, A. and Hoolachan, J. (2019) Generation rent’ and the emotions of private renting: self-worth, status and insecurity amongst low-income renters. Housing Studies, Early Access. CrossRef link

Meers, J. (2019) Khoo do you think you are? Licensees v tenants in the property guardianship sector. Journal of Housing Law, 22, 2, 24-27.

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) (2017) English Housing Survey 2015 to 2016: Private Rented Sector. London: MHCLG.

Pryce, G. and Oates, S. (2008) Rhetoric in the Language of Real Estate Marketing. Housing Studies, 23, 2, 319-348. CrossRef link

Reeves-Lewis, B. (2018) A new breed of rogue landlord. Journal of Housing Law, 21, 1, 17-22.

Rugg, J. and Rhodes, D. (2018) Vulnerability amongst Low-Income Households in the Private Rented Sector in England. Nationwide Foundation.