Abstract

This paper presents a brief historical analysis of the housebuilding industry in the UK, focusing on the impact of the 2008-09 recession on its activity and structure. It explores the process whereby the industry has been increasingly dominated by the biggest housebuilders. The paper draws lessons from postwar housebuilding programmes in the UK, and the priority given in that period to using plannable supply mechanisms. It describes how the shape of the industry has changed since then and focuses on the impact of the most recent recession. The authors show how the market share of the largest five housebuilders has increased during this period of austerity. The article discusses recent policy initiatives over housing supply, and concludes that they will fail to deliver the number of homes the UK is estimated to need. Future policy, the authors suggest, should seek to stimulate housebuilding by local authorities and other non-profit providers, whilst also boosting an emerging community-led sector.

Introduction

‘Austerity’ was one of the terms that was dusted down and brought back into regular usage to describe the economic condition of the country in the period following the financial collapse in 2008.1 It harked back to an earlier epoch. ‘Austerity Britain’ was the title chosen by David Kynaston (Kynaston, 2008) to describe the country in the immediate post-war period from 1945 to 1951. It was the first part of his magisterial and detailed social, economic and cultural history of the post-war era. The sub-title of Kynaston’s book was ‘Tales of the New Jerusalem’. Well, one can argue about the extent and impact of the current period of austerity, but there is little to suggest that the New Jerusalem is in sight. One of the most significant points of contrast with the post-war era in terms of housing policy is the more modest government aspiration about what can be achieved in terms of future levels of house-building.

It is often helpful to bring a historical sensibility to bear on contemporary policy analysis, especially in housing, given its durability as a physical asset, though one must also be careful not to overcook any apparent parallels. But one similarity between priorities in housing policy in the post war period and the post 2008 period is undeniable – the widespread view across the political spectrum that, whatever else is required, we need to build more homes. After the first age of austerity, more than 200,000 houses were built in the UK every year from 1951 for 31 consecutive years (HM Government, 2014a). By contrast, in the 23 years since 1990, annual housing completions exceeded 200,000 only five times. This period of lower output has coincided with a period of significant demographic change, which has exacerbated shortfalls in supply. Government estimates have suggested that 221,000 new households are now forming each year, in England alone (HM Government, 2013a).

Of course, there are other ways to increase supply other than through new housebuilding. These include improvements and conversions, measures to reduce the number of empty properties or, to take one policy recently suggested by Dorling (Dorling, 2014: 99-101), adjusting property taxation to encourage more efficient use of the housing stock – through a kind of ‘bedroom tax’ for the private sector. But it is widely accepted that such measures would still need to be complemented by an increase in current levels of housebuilding. A year-on-year expansion of housing output of ten per cent over the next ten years, for example, would not be enough on its own to close the gap between demand and supply.

The question of how to stimulate housing supply most effectively has prompted a recent flurry of inquests, committees and campaigns. The Chartered Institute of Housing has launched its ‘Homes for Britain’ campaign; the Labour Party has commissioned a review being chaired by Michael Lyons and due to report in September 2014 (Labour Party, 2014); and the government has recently announced a call for evidence into the role of local authorities in housing supply (HM Government, 2014b). In terms of policy, the government launched its Help to Buy programme in April 2013, and the Labour Party is consulting on a range of policies and setting new ambitious targets for housebuilding. Despite this, and the legacy of decades of under-supply, there is a pervasive and recurrent concern that government policies are fairly powerless to effect any change in the levels of output that can be achieved.

The factors involved in this record of under-achievement are manifold: in a summary of a high-level consultation on this issue, the Building and Social Housing Foundation listed a series of such reasons: land availability and price, planning delays, opposition to development, restrictions on public sector borrowing and the limited availability of private finance, limited mortgage availability, lack of affordability and the ‘current trader’ model operating in the construction industry (BSHF, 2013: 11). In this paper, we wish to explore one factor that is often neglected in such discussions, whether in high level seminars or around dinner tables – the changing structure of the housebuilding industry itself.

This paper therefore attempts to identify some lessons from the immediate post-war period of austerity, undertakes a brief analysis of the current housebuilding industry, and reflects on early findings about current interventions in the housing market. It begins with a historic perspective on housebuilding in the UK in the post-war period. The paper then considers the changing configuration of the private housebuilding industry in recent decades, most notably the emergence and increased market share of large firms. An analysis of the post-recession performance of the UK’s biggest housebuilders then follows. This raises important questions about current government interventions in the housing market, such as Help to Buy, and we explore some initial impacts of this programme. In conclusion, we discuss some of the underlying principles that might guide future policies directed at increasing housing supply.

The Balance between the Public and Private Sector: then and now

If one accepts that there needs to be a higher rate of building in the future, can anything be learned from the programme that was devised in the immediate post-war phase of austerity? The then Secretary of State for Health and Housing, Aneurin Bevan, was facing a crisis in housing supply that stemmed from various factors: the unfinished business from the slum clearance and redevelopment programmes of the 1930s, the demolition of large tracts of housing in many cities and the cessation of housebuilding during the war and, on the demand side, the demographic explosion of the baby boom. In response the Government launched the most ambitious programme of council housebuilding ever; four-fifths of the properties built in the period 1945-51 were in the public sector.

In recognising that the scale and nature of this national housing crisis took different forms in different localities, Bevan’s preferred approach was to support housebuilding by local authorities, rather than creating a monolithic centralised Housing Corporation (which was favoured in some quarters, not least by building trade unions) to do the job. Bevan promoted the building programme through relatively generous subsidies to local authorities. Private contractors had asked for a similar level of subsidy to help construct the minority of homes for sale. Bevan, according to his biographer, Michael Foot, threw that suggestion straight into the waste paper bin. He stated:

…if we are to have any correlation between the size of the building force on the sites and the actual provision of the material coming forward to the sites from the industries, there must be some planning. And if we are to plan we have to plan with plannable instruments, and the speculative builder, by his very nature, is not a plannable instrument. (Foot, 2009: 73)

This response was, as so often the case with Bevan, a marriage of pragmatism and idealism. In short, ‘needs must’ and the private builder would not build what was needed and on the scale required. The speculative builder would build where (and when) it was most profitable to do so. Also the private sector in the 1940s was dominated by small local builders, who would struggle to scale up sufficiently to meet the task ahead.

One can argue that the exigencies of the contemporary crisis of housing supply and affordability do not begin to compare with the scale of the post-war housing problems that Bevan was dealing with. And no major politician today has advocated a future housebuilding programme where four-fifths is devoted to socially rented housing. But the question of the appropriate balance between speculative building and public housing investment remains pertinent. Indeed, in the depth of the post-2008 recession, the case for large scale public sector housebuilding found some unlikely advocates.

The hedge fund advisers, Tullet Prebon, for example, in a succinct 2012 essay on the housing supply crisis, put the case for the state investing in housebuilding. This strategy would not suck in imports and in the long-term, the report suggested, it would be self-financing (increasing growth and revenue and reducing Housing Benefit expenditure). It went on:

We would stress that this (public) investment should be undertaken by local authorities or housing associations, not through public-private gimmicks like PFI…A national housebuilding programme should be a national economic imperative, not thwarted by sectoral self-interest or ideology. (Tullet Prebon, 2012)

Other unlikely advocates for greater public sector investment in housebuilding have included the Council for Mortgage Lenders (CML, 2014). The government, however, has unsurprisingly shown little interest in developing a neo-Bevanite response to the supply crisis. It is relying on the private sector to take up the reins of additional investment, through sustaining favourably low interest rates, pinning its hopes on the wider economic recovery and through the extension (announced in the 2014 Budget) of the Help to Buy scheme until the end of the decade. It is because private housebuilders are being almost singularly entrusted with delivering increased supply, that the structure of this industry merits close scrutiny. It is legitimate to ask whether private housebuilders can deliver the bulk of the 200-250,000 homes per year that are needed; and, if so, at what cost to the public purse?

The housebuilding industry in the UK: consolidation and concentration

The structure of the housebuilding industry has changed significantly since the late 1940s. While this is in itself scarcely surprising, various factors that are unique to the UK have meant that larger housebuilders have steadily increased their market share (Ball, 2003). Indeed past recessions, such as in the mid-1970s, have done much to shape this process of consolidation (Wellings, 2006: 84). As Cho (2011:3) notes, the corporate structures of large housebuilders has changed from ‘medium-sized regionally based firms…to multi-regional specialist homebuilders or subsidiaries of large conglomerates’.

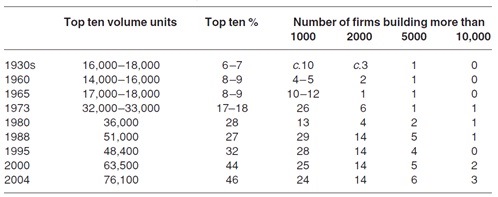

An analysis of the market share of the top ten housebuilders in the UK over the period 1960 to 2004, shows this process of consolidation unfolding. In 1960 the top ten housebuilders accounted for approximately nine per cent of all new housing production. By 2004 this had increased to 46 per cent as shown in Figure 1 below (Wellings, 2006: 105).

Ball (2007) provides two principal rationales for this long run process of consolidation. The first is that the spatial proximity of different markets and regions in the UK, compared to other advanced economies such as Australia and the U.S.A., makes diversification across these markets and regions easier. Larger firms are best placed to achieve ‘scale benefits’ from accessing these adjacent markets, which can in turn help spread or ‘pool’ risks (Ball, 2003). Secondly, as the availability of development land is more constrained in the UK, one of the most effective strategies for securing such land is through the takeover of other firms to access their land banks, leading to further consolidation. One significant example of this was the merger of Taylor Woodrow and George Wimpey in 2007, to create Taylor Wimpey, the UK’s second largest private housebuilder. A significant rationale for this merger was to create a bigger land bank (Building.co.uk, 2007a), and one which had longer term/higher risk sites combined with shorter-term/low risk sites with planning permission (Taylor Wimpey, 2008). The Housing Minister at the time, Yvette Cooper, warned that such mergers may lead to ‘reductions in the level of housebuilding delivery’ (Building.co.uk, 2007b).

As noted above, the restricted amount of development land in the UK has created a unique dynamic. Unlike in many other European countries, the restricted supply of land in the UK creates incentives for firms to combine both land development and housing construction functions. The larger sized firms that are created can therefore employ strategies to influence local land markets through their land banks. This is particularly the case for larger housebuilders, as Ball (2003: 909) notes:

…larger enterprises have employee skill-bases, capital-bases and land banks that enable them to spread risks, lower financing costs, improve negotiating positions with land-owners and facilitate strategic actions.

The issue of landbanking is complicated and contested. Leading politicians have recently suggested that developers are hoarding land with planning permission (Labour Party, 2013) and thereby restricting new housing supply. This has been countered with strong rebuttals and evidence that the landbanks of the large housebuilders are actually decreasing in size (Savills, 2013). Clearly, the availability of land is a key influence on the strategies of housebuilders, and these strategies are shaping a process of market consolidation.

The evidence for such consolidation, and the benefits that arise from this for the major players, have led to questions about competition in this market place. The Office of Fair Trading (OFT) examined this issue in 2008, and found ‘no evidence that individual housebuilders have persistent or widespread market power or that they are able to restrict supply or inflate prices’ (OFT, 2008: 6). The report accepts, in line with the Barker Review (2006), that, whilst housebuilders may operate at a national or regional level, they are competing in local markets, and it is local competition that largely determines their investment and development decisions.

The OFT suggested that, even where a housebuilder is a significant supplier of new homes in a locality, they are still unlikely to influence prices, and they found no evidence of housebuilders ‘anti-competitively hoarding land’ (OFT, 2008: 6). The concerns around the lack of competiveness are dismissed because housebuilders are not only competing with other housebuilders, but with the existing homeowners selling their properties on the second hand market. Firms can also enter and exit the housebuilding industry quite easily. Potential competitors are not, relatively speaking, prohibited from entering the market due to technological disadvantages or high entry costs. But there is a difference here between whether the market is in formal terms anti-competitive, and whether it is overly risk averse and not functioning as responsively as it might to help meet government policy ambitions. The increasing elision between house production and land ownership becomes relevant here. This has led some politicians to propose measures to force housebuilders to develop land with planning permission within a certain time frame (Miliband, 2013; London Evening Standard, 2013).

There is certainly evidence, therefore, of increasingly ‘centralised and oligopolistic’ structures (Healey and Barratt, 1990: 96) in the housebuilding industry. It is because this market is not delivering sufficient new homes, in a context of rapid household formation (HM Government, 2013a) and rising prices (Nationwide, 2013), that it is important to monitor recent trends in the industry. Clearly the structure of any industry – entries and exits, processes of consolidation or divergence – will be affected at different points in the economic cycle. So, if the pre-recession ‘boom’ witnessed a growth in consolidation among the major construction companies, what happened in the contrasting period of economic recession from 2008 onwards?

Post-recession trends: The top five housebuilders

The housebuilding industry is particularly susceptible to recessionary forces and cyclical fluctuations in the housing market (Ball, 2003). In 2007-08 total housing completions in the UK stood at 219,000. However, by 2012-13 this had slumped to a post-war low of 135,000 (HM Government, 2013b). This prompted suggestions from within government that the industry had been ‘brought to its knees’ (Shapps, 2011). In fact, we suggest that this general picture, of the fragility of the financial position of housebuilders, and their consequent need for greater public sustenance to stay afloat, is questionable.

It became accepted wisdom that the 2008-09 recession had a ‘particularly large impact’ on the UK housebuilding industry (HM Government, 2013c: 5; see also Mirror, 2008; Daily Mail, 2012). At the height of the recession, there were genuine concerns about the solvency of the biggest firms, reflected in the raft of profit warnings issued in 2008 (The Guardian, 2008; This is Money, 2008). The construction sector is often portrayed as being particularly vulnerable to downturns in the economic cycle, being the first to feel the cold chill of recession and the last to feel the warmth of any subsequent recovery (Construction Industry Council, undated). However, our analysis of key financial information relating to the biggest housebuilders in the UK tells a more complicated story. We undertook an analysis of the annual reports of the five housebuilders with the largest revenues in 2012 (Building.co.uk, 2012).2 The charts below present some of this analysis, shedding light on the strategies that such organisations employ in periods of economic decline.

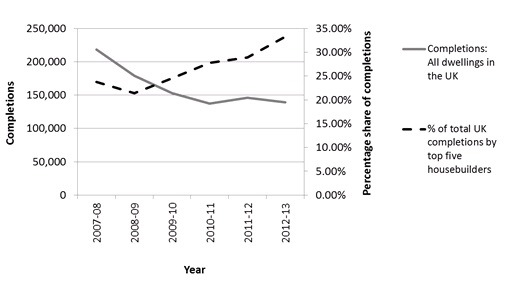

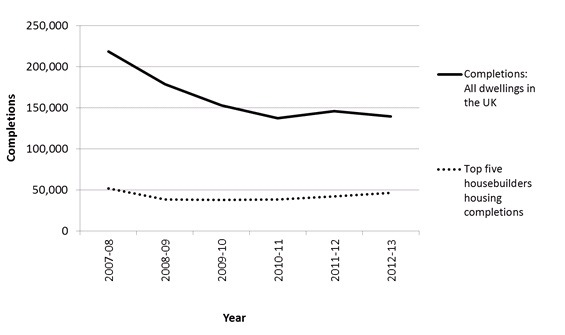

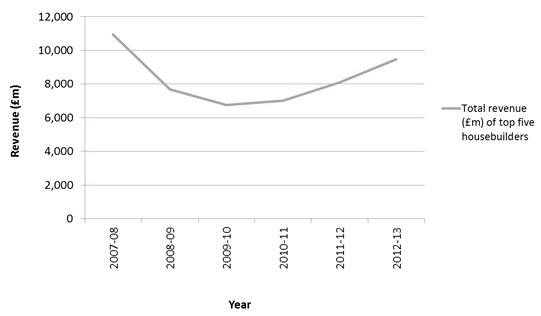

Figure 2 shows the housing completions of the five largest housebuilders (henceforth ‘the Big Five’) compared to the total housing completions in the UK.3 Figure 3 plots the annual revenues of the Big Five over the same period. It is clear from Figure 2 that between 2008-09 and 2012-13 completions in the UK declined markedly, as the lagged effects of the recession emerged. In contrast, the Big Five actually increased their housing completions year-on-year over this period, albeit very marginally. Figure 3 shows the product of this building activity in terms of the Big Five’s revenue and it shows how, over the same period, their revenues grew from £6.8bn to £9.5bn.

A comparison of the two charts is instructive. The exponential growth in the revenues of the Big Five was not commensurate with their output; in essence, they were generating significantly more revenue without having to build an equivalent increase in the number of homes. Revenues between 2009-10 and 2012-13 grew by 40 per cent, compared to a 24 per cent increase in output.

Figure 2: Housing completions 2007-08 to 2012-13: All dwellings in the UK and the Big Five

Sources: Annual reports of top five housebuilders as declared by Building.co.uk (2012); HM Government (2013b).

Figure 3: The Big Five’s combined revenues 2007-08 to 2012-13

Sources: Annual reports of top five housebuilders

During this period, the big housebuilders were adopting a strategy of ‘prioritising margin over volume’ (Taylor Wimpey, 2011), or ‘maximising value rather than driving volumes’ (Barratt Developments PLC, 2011: 5). In the midst of the recession and shortly after it, big housebuilders focused on squeezing as much as possible from the most profitable sites, rather than maximising their overall housing output. As a result, units were sold at a higher average price in 2011 than in the year before (Barratt Developments PLC, 2011; Berkeley Group, 2011). This was despite a backdrop of declining house prices nationally (ONS, 2014).

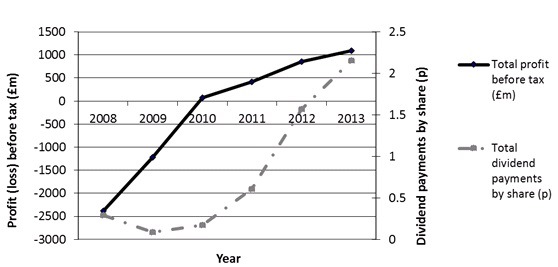

Further to this evidence we can see how the Big Five’s profit-before-tax was increasing from 2010 onwards (see Figure 4 below). Similarly their dividend payments to shareholders were increasing from 2009, albeit from a low base. All this suggests that the big housebuilders were not ‘on their knees’ (Shapps, 2011) for long after the recession.

The recessionary period is also interesting in terms of the Big Five’s share of total housing output. Figure 5 below shows the group’s completions as a percentage of all completions in the UK. As can be seen, the group’s share of housing production over the five year period has steadily increased, giving further signs of consolidation in the market.

This analysis does not represent an extension of Wellings’ market share analysis (as detailed in Figure 1 above) since different datasets and methods of aggregation have been used. Nonetheless, the evidence presented here suggests we can concur with Wellings about the impact of past recessions on the housebuilding industry, notably that they lead to market consolidation. Whilst Wellings’ work pre-dates the 2008-09 recession, our data suggests that similar processes of consolidation took place during and after the most recent recession as well.

This is not to deny that the 2008-09 recession had an immediate impact on the financial stability of the wider housebuilding industry, seen most clearly in plummeting share prices and lost value from the sector (House-builder.co.uk, 2008). Workforce surveys suggested that those in the construction sector, more than any other, felt the recession had adversely affected their industry (Van Wanrooy et al, 2011). However, the response of the biggest housebuilders to these difficulties was significant. They adopted strategies to deal with falling asset values and weakening demand for their housing, for instance, by focusing on sites with greater profit margins or disposing of assets to raise cash (Berkeley Group PLC, 2011).

These strategies were clearly effective, and the biggest housebuilders were far more resilient than many sections of the media suggested (The Mirror, 2008; Daily Mail, 2012). Housing completions in the UK were not as resilient, however, and whilst 2014 may see a rise in completion levels, it will fall some way short of addressing the shortage of supply, even according to more modest estimates. This outcome reflects a recurrent theme in housing policy debates over the past forty years: whether the market, in its current form and structure, can come near to delivering the amount of housing required, whichever estimate is adopted. It also raises questions about what, if anything, the government should do in response to the consistently low level of housing outputs, at quite different points in the economic cycle, and the increasing market share by a handful of companies.

Help to Buy: mitigation or exacerbation?

Help to Buy is the current government’s major initiative in response to problems in housing supply, and it is interesting to assess it in reference to our preceding analysis. There are two elements to the programme; the first is an equity loan scheme which applies to new housing only, and the second is a mortgage guarantee scheme which applies to existing housing. The programme is explicitly seeking to ‘boost housing supply’ (Treasury, 2014: 3). At a more ideological level it is driven by a desire to give ‘thousands more people the security and independence that comes from owning their own home’ (HM Government, 2014c). The Help to Buy equity loan scheme is forecast to support the development of 74,000 new homes by 2016, which would amount to a contribution of 24,700 units per year. The 2014 Budget extended this element of the programme to 2020, and forecasted it would add an additional 120,000 units between 2016 and 2020.

Early assessments of both schemes have led to divergent opinions about the impact of the programme. Advocates of Help to Buy have highlighted how, in the first nine months of the initiative, over 17,000 sales have been directly supported by the equity loan scheme, with 89 per cent of these sales going to first time buyers (Inside Housing, 2014a). Others argue that the programme has boosted the confidence of housebuilders, reassuring them that ‘they can sell what they build, which…means they want to build more’ (The Telegraph, 2014). The government has been quick to highlight that there was a 23 per cent increase in housing starts in 2013 compared to 2012. However, it is hard to decipher how much of this is attributable to the Help to Buy programme, and how many of these units would have been built anyway.

Critics of the programme argue that Help to Buy is fuelling yet another housing bubble. In 2013 the IMF warned that the programme would result in house price increases that would ‘work against the aim of boosting access to housing’ (IMF, 2013). This argument has been repeated by The Priced Out campaign. It recently showed that the rise in house prices, which has occurred since Help to Buy started, has meant 200,000 more households are unable to purchase a property (Priced Out, 2014). This renders the achievement of Help to Buy, in supporting 31,000 first time buyers, rather less impressive. Some gain, but many others lose out.

The Adam Smith Institute has developed a critique of the underlying structure of the programme, rather than its impact on housing output. It argues that Help to Buy is merely ‘assisting buyers by subsidising additional borrowing’ (Adam Smith Institute, 2013: 1). This is not only reducing affordability for everyone else, it is also increasing the amount the programme has to invest or guarantee. Indeed the programme has a striking resemblance to the American mortgage securitisation programmes Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the prime instigators of the financial collapse in the USA in 2008 (Acharya et al, 2011). Far from being risk free and cost neutral, the mortgage guarantee element of Help to Buy creates a significant ‘contingent liability’ for the British taxpayer (Adam Smith Institute, 2013). Even if the bubble does not burst, and history suggests it will, it is storing up potentially huge problems for a future government if defaults start to increase.

This debate highlights a recursive process inherent in the Help to Buy programme. Its initial impact was to increase confidence in the housing market, which in turn has led to a growth in house prices. This price growth has meant that more people are excluded from the market than have actually been supported. At the same time, price increases are placing ever more demands on the funding available within the programme, as the cost of equity loans increases. In a context where interest rates are likely to rise, those at the margins of affordability (such as those supported by Help to Buy) are most at risk of defaulting. This makes the ‘contingent liability’ to the taxpayer, arising from Help to Buy, ever more likely to be realised. Due to these recursive processes, one must question whether Help to Buy can be a sustainable solution to the under-supply of housing.

One thing is clear about the Help to Buy programme: large housebuilders have benefited from it. Since its launch, the share price of Barratts has increased by 60 per cent, and Taylor Wimpey and Persimmon have both seen 40 per cent increases (Inside Housing, 2014a). While other factors have also played a part in prompting these increases, the act of faith taken by the government to de-risk mortgage debt through the Help to Buy programme has undoubtedly been a primary reason for the recent spike in share price levels of the larger developers. When the Chancellor of the Exchequer announced in March 2014 that the equity part of the Help to Buy programme would be extended from 2016 to the end of the decade, in the following day of trading shares in Persimmon rose by four per cent, by three per cent in Barratts and by two per cent in Taylor Wimpey (The Guardian, 2014). This suggests that the Help to Buy programme may intensify the process of consolidation in the market, in supporting the biggest housebuilders to increase the value of their companies.

Conclusion

Public subsidy directed to stimulate private investment may often have unforeseen consequences, which benefits the investors more than any potential consumers. Sixty-five years ago, Bevan’s verdict on the suggestion made by the Conservative Party that private housebuilding should be subsidised, offers a prescient view about current initiatives like Help to Buy. He said:

The only remedy the Tories have for every problem is to enable private enterprise to suck at the teats of the state. (Foot, 2009: 78)

As Bevan understood, what makes the ‘speculative builder’ unplannable is the operating logics that drive them; profit comes before output. There is clear evidence of this logic at work in the midst of the most recent recession. As we have seen, some of the biggest housebuilders were prioritising margin over volume, as they retrenched, minimising risks to themselves and restricting their output. But what happens when recessions end? Is there then an incentive to ‘prioritise volume?’ History clearly suggests that this will not be the case, without additional direct public intervention. Acting ‘strategically’, large housebuilders will be selective about when they release properties onto the market to control the supply, and therefore prices (Ball, 2003). The profit motive does not sit easily alongside any government commitment to achieve a sustained increase in housing supply. And a more emaciated state in the early part of the twenty first century means that any latter day Bevan will not have other levers as readily to hand.

On the demand side, the UK housing market is changing rapidly, for a host of reasons, many of them unrelated to any formal government ‘housing’ policies. The private rented sector, for example, constituted 10 per cent of the housing stock in 2001, but by 2012 this had increased to nearly 18 per cent (HM Government, 2014d). The proportion of households in the owner-occupied sector has started to undergo a structural decline and, with or without Help to Buy, this long term trend is unlikely to be reversed in the future (Heywood, 2011). Generation Rent is here to stay. Around the margins of the mainstream tenures, a wide spectrum of intermediate responses can be seen – the buy-to-let market, housing associations moving more strongly into market rent, shared ownership, leasing arrangements, new variants of social housing, co-operative and mutual housing initiatives, and so on. This variegated picture is not matched, however, in housing supply. The big beasts just grow bigger, rationalisation and risk aversion prevail, public subsidy is misdirected and developers show little interest in sharply increasing output to meet public policy objectives.

There is a future role for the state here, if one accepts that, following Mazzacuto (2011), the state has often been, and can still be, a stimulus to innovation rather than the ‘dead hand’ that it is often portrayed to be. Rather than future output being increasingly dependent on the demands and strategic priorities of a handful of private companies, diversifying the market would offer a different way forward. In fact, both the Labour and Conservative parties have implicitly acknowledged this, proposing policies to support SME builders (Inside Housing, 2014b; HM Treasury, 2014: 3). This could be supplemented by working with partnerships of medium-sized housing associations (like the current ‘Placeshapers’ group) to develop joint investment programmes alongside the larger associations. In addition, policies could be introduced to ease borrowing for local authorities to encourage them to develop more affordable homes, whilst also supporting an emerging community-led development sector.

The recent growth of community lands trusts and other mutual models shows there is an appetite for non-profit, localised development organisations, and we increasingly understand what incentives and technical support they need to grow (Mullins and Moore, 2013). The most interesting aspect of these models is their capacity to keep house prices and rental costs affordable by insulating them from market forces (Paterson and Dayson, 2011), as well as their ability to develop sites that for-profit developers have not been able to make viable (MacTiernan, 2012; The Guardian, 2012). Such initiatives may be financed in novel ways, such as via a special Housing Bank, which would place less liability on the taxpayer (Jefferys et al, 2014). The combined effect of dramatically extending such initiatives would be to diversify the structure of housing supply, in the face of an increasingly diverse profile of housing demand.

The current regime for public investment in housing lacks imagination and flexibility. Funding more experimental schemes and new models would be a much more productive call on public resources than as a saviour of last resort for future mortgage defaulters. The clock cannot be turned back to the policy challenges of the post-war period of austerity. But the exercise of trying to achieve public policy objectives in housing supply, through using unplannable instruments to deliver them, is likely to be as self-defeating now as it would have been sixty-five years ago, if Aneurin Bevan had not decided to consign the idea to the waste paper bin.

1 We have framed the term ‘austerity’ with inverted commas due to our own unease about the widespread use of this term – an unease well expressed by John Lanchester (2014:33) as follows:

In everyday life, ‘austere’ means simple, strict, severe. But that general quality doesn’t really refer to anything tangible, which is a problem, since what we are talking about here is spending cuts. Funds are either cut or they aren’t. The word ‘austerity’ is an attempt to make something moral-sounding and value-based out of specific reductions in government spending that result in specific losses to specific people.

2 In order of size of revenue, starting with the largest, the following firms were studied; Barratt Developments PLC, Taylor Wimpey PLC, Persimmon PLC, Berkeley Group Holdings PLC, and Bellway PLC.

3 The annual reports of each of the Big Five cover different time periods, as each company has its own ‘year-end’. Aggregated data does not therefore align exactly with a fiscal or calendar year. This in turn means there is some inevitable misalignment with the government’s data on total UK completions.

Tom Archer, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University, City Campus, Howard Street, Sheffield S1 1WB. Email: thomas.archer@student.shu.ac.uk

Acharya, V.V., Richardson, M., Van Nieuwerburgh, S. and White, L.J. (2011) Guaranteed to Fail: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Debacle of Mortgage Finance. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Adam Smith Institute (2013) Briefing Paper: Burning down the house; Government is not the solution to the housing crisis [online]. Last accessed 15 April 2014 at http://www.adamsmith.org/research/reports/burning-down-the-house-why-help-to-buy-will-ruin-britains-housing-market-0

Ball, M. (2003) Markets and the Structure of the Housebuilding Industry: An International Perspective. Urban Studies, 40 (5-6), pp. 897-916. CrossRef link

Ball, M. (2007) Firm size and competition; a comparison of the housebuilding industries in Australia, the UK and the USA. Working papers in Real Estate and Planning, 02/07, Reading, Reading University.

Barratt Development PLC (2011) Annual Results Announcement for the year ended 30 June 2011 [online]. Last accessed on 30 November 2013 at http://www.barrattdevelopments.co.uk/barratt/en/investor/results

Berkeley Group PLC (2011) Preliminary Results Announcement 24th June 2011 [online]. Last accessed on 18 June 2014 at http://www.berkeleygroup.co.uk/investor-information/results-and-announcementsBuilding and Social Housing Foundation (BSHF) (2013) Creating the Conditions for New Settlements in England. BSHF (no place of publication).

Building.co.uk (2008) Housebuilders’ shares plummet [online]. Last accessed 26 November 2013 at http://www.building.co.uk/housebuilders-shares-plummet/3115562.article

Building.co.uk (2007a) Taylor Wimpey merger creates UK’s biggest housebuilder [online]. Last accessed 14 June 2014 at http://www.building.co.uk/taylor-wimpey-merger-creates-uks-biggest-housebuilder/3083761.article

Building.co.uk (2007b) Cooper voices concern over housebuilding mergers [online]. Last accessed 14 June 2014 at http://www.building.co.uk/cooper-voices-concern-over-housebuilding-mergers/3085627.article

Cho, Y. (2011) The UK Housebuilding Industry; An Analysis of Post-Barker Structural Responses [online]. Last accessed 1 March 2014 at http://oisd.brookes.ac.uk/resources/OISDworkingpaper2Sept2011.pdf

Construction Industry Council (CIC) (undated, but probably 2008) The Impacts of the Recession on Construction Professional Services: A View from an Economic Perspective. London: CIC.

Council for Mortgage Lenders (CML) (2014) Response by CML to the independent housing commission chaired by Sir Michael Lyons (12.2.14). Available from: http://www.cml.org.uk

The Daily Mail (2012) UK economy’s recession could be WORSE than thought after construction output slumps [online]. Last accessed 11 November 2013 at http://www.dailymail.co.uk/money/news/article-2142970/Poor-construction-output-quashes-hopes-Q1-GDP-better-thought.html

Dorling, D. (2014) All That is Solid: The Great Housing Disaster. London: Allen Lane.

Foot, M. (2009) Aneurin Bevan: A Biography: Volume 1. London: Faber & Faber.

The Guardian (2008) Rising mortgage costs slow new home sales [online]. Last accessed on 24 March 2014 at http://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/apr/18/taylorwimpey.mortgages

The Guardian (2012) This is how we solve the housing crisis – one home at a time. [online]. Last accessed 1 May 2014 at http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/aug/13/solve-the-housing-crisis

The Guardian (2014) Help to Buy extension boosts housebuilders’ shares, 17 March 2014 (on line)

Healey, P. and Barratt, S.M. (1990) Structure and Agency in Land and Property Development Processes: Some Ideas for Research. Urban Studies, 27, 1, 89-103. CrossRef link

Heywood, A. (2011) The End of the Affair: Implications of Declining Home Ownership. London: Smith Institute.

HM Government (2006) Barker Review of Land Use Planning: final report recommendations – Full Text [online]. Last accessed 1 March 2014 at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/barker-review-of-land-use-planning-final-report-recommendations

HM Government (2013a) Household Interim Projections, 2011 to 2021, England [online]. Last accessed 27 November 2013 at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/190229/Stats_Release_2011FINALDRAFTv3.pdf

HM Government (2013b) Live table 209: House building: permanent dwellings completed, by tenure and country [online]. Last accessed 20 February 2014 at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-house-building

HM Government (2013c) Construction Industry Briefing Note SN/EP/1432 [online]. Last accessed 20 November 2013 at www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/sn01432.pdf

HM Government (2014a) Live table 241: House building: permanent dwellings completed, by tenure [online]. Last accessed 16 April 2014 at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-house-building

HM Government (2014b) Review of local authority role in housing supply: call for evidence [online]. Last accessed 1 April 2014 at https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/review-of-local-authority-role-in-housing-supply-call-for-evidence

HM Government (2014c) PM hails Help to Buy success [online]. Last accessed on 1 April 2014 at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-hails-help-to-buy-success

HM Government (2014d) Live Table 101: By tenure, United Kingdom (historical series) [online]. Last accessed 1 May 2014 at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-dwelling-stock-including-vacants

HM Treasury (2014) Budget 2014 [online]. Last accessed in 13 April 2014 at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/budget-2014-documents

House-builder.co.uk (2008) Barratt shares lose 25% of value in a day [online]. Last accessed on 13 March 2014 at http://www.house-builder.co.uk/news/articles/2008-06-11/barratt-shares-lose-25-of-value-in-a-day.html

Inside Housing (2014a) Impact of Help to Buy revealed [online]. Last accessed 17 April 2014 at http://www.insidehousing.co.uk/impact-of-help-to-buy-revealed/7003199.article

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2013) United Kingdom—2013 Article IV Consultation Concluding Statement of the Mission [online]. Last accessed 15 April 2014 at https://www.imf.org/external/np/ms/2013/052213.htm

Inside Housing (2014b) Reynolds announces measures to help Labour reach 200,000 homes a year target [online]. Last accessed 17 April 2014 at http://www.insidehousing.co.uk/reynolds-announces-measures-to-help-labour-reach-200000-homes-a-year-target/7001609.article

Jefferys, P., Lloyd, T., Argyle, A., Sarling, J., Crosby, J. and Bibby, J. (2014) Building the homes we need: A programme for the 2015 government [online]. Last accessed 1 May 2014 at http://england.shelter.org.uk/news/may_2014/house_prices_could_quadruple_if_we_dont_act,_warn_kpmg_and_shelter

Kynaston, D. (2008) Austerity Britain 1945-1951: Tales of a New Jerusalem. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Labour Party (2014) Your Britain: The Lyons Housing Review [online]. Last accessed on 1 April 2014 at http://www.yourbritain.org.uk/agenda-2015/policy-review/policy-review/lyons-housing-review

Labour Party (2013) Ed Miliband to declare that a One Nation Labour Government will back home builders and first time buyers [online]. Last accessed on 1 April 2014 at http://press.labour.org.uk/post/70134771056/ed-miliband-to-declare-that-a-one-nation-labour

Lanchester, J (2014) Money talks. Learning the Language of Finance. New Yorker. 4 August 2014 pp30-33

London Evening Standard (2013) Start building or I’ll make you sell land, Mayor Boris Johnson tells developers [online]. Last accessed 28 November 2013 at http://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/start-building-or-ill-make-you-sell-land-mayor-boris-johnson-tells-developers-8629130.html?origin=internalSearch

MacTiernan, K. (2012) How to… set up an urban Community Land Trust [online]. Last accessed on 23 January 2013 at http://www.cles.org.uk/features/how-to-set-up-an-urban-community-land-trust/

Mazzucato, M. (2011) The entrepreneurial state. London: Demos.

Miliband, E. (2013) The Discipline to Make a Difference – National Policy Forum [online]. Last accessed 29 November 2013 at https://www.labour.org.uk/the-discipline-to-make-a-difference—ed-miliband

The Mirror (2008) Alistair Darling has a duty to shore up our builders [online]. Last accessed 12 November 2013 at http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/alistair-darling-has-a-duty-to-shore-up-314306

Mullins, D. and Moore, T. (2013) Scaling Up or Going Viral: Comparing self-help housing and community land trust facilitation, Third Sector Research Centre.

Working Paper 94 [online]. Last accessed on 1 April 2014 at http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/generic/tsrc/research/service-delivery/housing/wp-94-comparing-self-help-housing-community-land-trusts.aspx

Nationwide (2013) UK House Prices since 1952 [online]. Last accessed 23 November 2013 at http://www.nationwide.co.uk/hpi/datadownload/data_download.htm

Office of Fair Trading (2008) Homebuilding in the UK: A Market Study [online]. Last accessed 23 March 2014 at www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/reports/comp_policy/oft1020.pdf

Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2014) Table 22 Housing market: house prices from 1930, annual house price inflation, United Kingdom, from 1970 (DCLG table 502) [online]. Last accessed 18 June 2014 at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/hpi/house-price-index/march-2014/stb-march-2014.html#tab-Data-Tables

Paterson, P. and Dayson, K. (2011) Proof of Concept: Community Land Trusts. Salford: Community Finance Solutions.

Priced Out (2014) Help to Buy prices out six times more people than it helps [online]. Last accessed on 12 April 2014 at http://www.pricedout.org.uk/news

Savills (2013) Market in Minutes: UK Residential Development Land [online]. Last accessed on 18 June 2014 at http://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/173558/169639-0

Shapps, G. (2011) ‘Build Now, Pay Later’ announcement [online]. Last accessed 27 November 2013 at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/grant-shapps-offers-build-now-pay-later-deal-to-developers

Taylor Wimpey (2011) Results for the year ended 31 December 2010 [online]. Last accessed on 12 April 2014 at https://www.taylorwimpey.co.uk/corporate/investor-relations/reporting-centre/2011

Taylor Wimpey (2008) Achieving business benefits [online]. Last accessed on 12 April 2014 at http://taylorwimpeyar2007.hemscottir.com/tw-14-business-review

The Telegraph (2014) Happy birthday for Help to Buy loans? [online]. Last accessed on 13 April 2014 at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/10733146/Happy-birthday-for-Help-to-Buy-loans.html

This is Money (2008) Bellway profit warning as house prices fall [online]. Last accessed 29 November 2013 at http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/markets/article-1632248/Bellway-profit-warning-as-house-prices-fall.html

Tullett Prebon (2102) Building a Road to Recovery [online]. Last accessed 14 April 2014 at http://www.tullettprebon.com/strategyinsights/

Van Wanrooy, B., Bewley, H., Bryson, A., Forth, J., Freeth, S., Stokes, L. and Wood, S. (2011) The 2011 Workplace Employment Relations Study [online]. Last accessed on 21 March 2014 at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-2011-workplace-employment-relations-study-wers

Wellings, F. (2006) British Housebuilders: History and Analysis. Oxford: Blackwell. CrossRef link