Abstract

School food policy sets ambitious targets for improving child health and wellbeing through the provision of a nutritionally balanced school lunch, but there is very little evidence that policy and legislation designed to improve the quality of school food is having a positive impact on either the number of children choosing a school meal, or on improving children’s health. This paper reports on findings from an institutional ethnography carried out in three UK primary schools between 2017 and 2019 to explore the issue of low meal uptake. It discusses the spatial issues that school food workers reported as impacting upon their work and traces these issues to a divergence between school food policies and building design processes. It concludes with recommendations for policy makers to reconsider the spatial implications of school food policies that seek to increase uptake, and to work with the accounts of school food workers to improve policy impact.

Introduction

The policy environment surrounding school food is a complex and demanding one, in which a meal served to children at lunchtime is framed as an essential factor mitigating population health inequalities, as well as being important in the social development of children and young people (Mazarello et al., 2015; Impact on Urban Health, 2022; Illøkken et al., 2021; Adamson et al., 2013; School Food Plan, 2014). The work of delivering effective school food policy rests upon a number of assumptions, including the capacity of the current system to deliver a wide range of healthy and appealing choices and respond to the policy aspiration of increased uptake (Department for Education, 2023; Dimbleby and Vincent, 2013). The people who are tasked with delivering these increasingly complex and demanding policy promises are primarily school cooks and lunchtime supervisors working within resource allocations over which they have very little control.

This paper reports on findings from an institutional ethnography carried out in three UK primary schools between 2017 and 2019 which set out to explore the issue of low uptake, particularly amongst children entitled to a free school meal. An objective of my research was to identify the barriers to successful policy application and make recommendations that could support improved policy impact.

The project identified a number of factors that were impacting meal uptake, including a lack of familiarity with the food on offer, and a preference for packed lunches brought in from home (Hawkins and Rundle, forthcoming) and pressures of delivering the aspirations of school food policy within the kitchen and dining spaces available. This paper reports on findings that relate specifically to the design and use of kitchen and dining space, and how these were found to shape the practice of school lunch. In focusing upon this specific area of findings I hope to make a clear argument for improving the design process for school kitchen and dining spaces, but in doing so I also acknowledge that the research identified other factors shaping meal uptake and impact that are discussed elsewhere (Hawkins, forthcoming; Hawkins and Rundle, forthcoming).

The practice of school lunch includes the work to design, promote, cook, serve, and eat the food. Practice theory as a conceptual lens encourages a focus upon the materiality of the local environment, exploring how spaces, as well as cultures, shape the performance of the practices (Vihalemm et al., 2015). This approach has been used to explore the evolution of home heating and daily travel practices as new ways of understanding barriers to adopting more environmentally sustainable behaviours (Shove et al., 2012; Batel et al., 2016).

The research framed school lunch as a complex social practice, something that many people identify with as a concept, often built upon their own experience of school meals and the presentation of the practice in popular culture (Vilhalemm et al., 2015). For example, in Norway, the norm is for children to bring in a packed lunch from home and eat it at individual desks (Illøkken et al., 2021), whereas in the USA pupils queue and select from a range of (usually heavily processed) food options and eat at communal tables, a practice commonly depicted in popular culture (Best, 2017). In the UK depending upon when you went to primary school, you may remember school lunch as a single meal option being served onto a plate at your table, or from a service hatch, or being able to select from a range of meal options or bringing in a packed lunch from home (Rose et al., 2019).

School lunch is subject to variations in the way that the practice is performed in different contexts, often managing competing narrative assumptions and policy directives around what good food choices and behaviours are. These variations will include: how food is provided (by the school or brought in from home); what variety of food is offered (if any) and how selections are managed; how meals are paid for; what kinds of food and drinks are permitted and acceptable for consumption in school; where and when lunch is consumed in school; how seating is arranged, and how food is served and eaten. The practice is more than the food, it encompasses the norms, patterns, processes and emotions connected with the practice, and whilst these can be unified under the heading ‘school lunch’, the memories and associations that this term triggers will vary depending upon individual experience and memory.

Viewing school lunch through a practice lens allows for the exploration of how the practice has evolved over time, and what forces have shaped this morphology. Seeing practices as dynamic and contextual recognises that there will be differences between the official account of school lunch found in policy and research and the way that it happens in different places at different times. In the case of school lunch there is compelling evidence that the primary task of improving children’s dietary health is having limited success, particularly when looking for long-term indicators of improved diet or health (d’Angelo et al., 2020; Kitchen et al., 2010; Black et al., 2017) and that the school meals service is struggling to win customers in a competitive environment, whilst also adhering to statutory nutritional standards. For the school meal service to remain viable it is essential that the majority of children take up the option of a school lunch in order for economies of scale to be felt, and yet many school meals services are struggling to compete with packed lunches brought from home (Dimbleby and Vincent, 2013; Stevens et al., 2013).

This work makes a unique empirical contribution to the understanding of school food policy implementation from the perspective of school food workers whose accounts and experiences are almost entirely missing from school food policy and research. As the people delivering these policies at the front line, these perspectives can make a valuable contribution to knowledge, especially when trying to understand why policies are not having the desired impact. The majority of existing school food research focuses upon the nutritional rationale for school meal uptake (Dimbleby and Vincent, 2013; Food Foundation, 2022; Impact on Urban Health, 2022), in particular how school lunches are healthier than packed lunches (Parnham et al., 2022; Andersen et al., 2015). There is very little research that explores the design and use of spaces used in the preparation, service, and consumption of school meals, or that considers these spatial factors as contributors to the evolution of the practice. My work seeks to map the power dynamics that are shaping practices, and to identify meaningful intervention points that could support improved levels of uptake of school meals. This paper concludes by drawing upon the experiences of school food workers to provide policy recommendations to help achieve desired levels of school meal uptake.

Literature review

Power in Practices

This study talks about the practice of school lunch and in doing so adopts a practice theory frame. Practice theory offers a compelling challenge to dominant theories about the drivers of human action, and in particular the drivers of consumer ‘behaviour’ that represent a significant body of academic work and, crucially, continue to dominate policy development (Shove, 2010). Practice theory as a challenge to the ‘behaviour change’ paradigm requires a reorientation of focus, away from the individual as a lone agent making individualised decisions informed by knowledge of and attitudes towards available choices. Instead, it suggests that the central topic of enquiry should be ‘social practices ordered across time and space’ (Giddens, 1984: pp. 2-3). The recognition that practices are dynamic makes practice theory such a useful way of exploring how change takes place in everyday life (Shove et al., 2012), and in the context of this research, how the practice of preparing and serving a school lunch has changed over time.

Whilst practice theory has been instrumental in challenging individualised approaches such as theories of planned behaviour, social marketing, and ‘nudge’ (structuring options so that a particular choice is prioritised), it is acknowledged that it does not adequately account for the role that ‘power’ plays in shaping social practices (Watson, 2014; Vihalemm et al., 2015). Power within an institutional context such as school food can be identified in the processes that feel remote to workers on the front line. For example, the policies and processes that determine school kitchen design can be experienced by school kitchen staff negatively, making their work harder, yet they feel powerless to influence these processes.

Many studies that focus upon the ways in which the social organisation of everyday life works to reproduce inequality recognise that it is important to identify (and in most cases, challenge) what are variously described as ‘structures of power’ (Cahill, 2007: p. 279, Weis and Fine, 2012: p. 173), ‘ruling relations’ (Smith, 2008), and ‘spatial embeddedness of power’ (Kesby, 2007: p. 2827), processes which are argued to reproduce ‘circuits of dispossession and privilege’ (Weis and Fine, 2012: p. 187). An example of this would be Dorothy Smith’s study of the extent to which Canadian elementary schools relied upon the unpaid work of mothers to support the work of the school, and the disadvantages experienced by children whose mothers were involved with paid work that precluded this (Smith, 2005). IE is deployed here not only as a method for exploring hidden work, but also as a way of foregrounding the power that institutional (and other) processes exert to shape how work is done.

School Food: the UK Policy Context

School meals emerged in the mid-nineteenth century as a philanthropic response to concerns about the poor physical health caused by malnutrition in the nation’s children. It remained a fragmented and localised provision until 1941 when the first national school meals policy and nutritional standards were launched. The Education Act of 1944 made provision of school meals a duty of all Local Education Authorities (LEAs) with the full net cost being met by Government from 1947. A standard charge was introduced for meals in the 1950s and full financial responsibility for the delivery of a school meals service passed to LEAs in 1967 (Evans and Harper, 2009).

School food in the UK was deregulated in the 1980s which meant that the provision of school meals was no longer a statutory obligation required of LEAs. Nutritional standards were abolished, as was the fixed national price of a school meal (UNISON, 2005). In response to this cost-cutting measure, some LEAs stopped providing a catering service. In 1986 free school meals were limited to children whose parents received means-tested benefits and in 1988 the Local Government Act was passed which required LEAs to put the meals service out to competitive tender. This ‘lowest bid wins’ approach prioritised economic efficiency over nutritional quality, with predictably detrimental impact upon the latter (Rose et al., 2019).

In response to concerns that this process had a harmful effect upon the quality and uptake of school meals, since 2000 each UK country has reintroduced food standards on either a voluntary or compulsory basis. School food in England is regulated by ‘The Requirements for School Food Regulation 2014’ a statutory instrument which came into force in 2015, and which sets out the nutritional standards for the food provided in the majority of schools in England; grant-maintained or ‘private’ schools are excluded from this legislation (UK Government, 2014; School Food Plan, 2014).

The ’Requirements for School Food Regulation 2014’ has been supported by a number of guidance documents since its publication. Current guidance states that:

A great school food culture improves children’s health and academic performance. Increasing the take-up of school meals is also better for your school’s finances. A half-empty dining hall – like a half-empty restaurant – is certain to lose money…Your school has a unique role to help children learn and develop good healthy eating habits for life, creating happier, healthier adults of the future. (Department for Education, 2003)

Compliance with current school food standards, although a statutory requirement for all state-funded primary schools, is not systematically monitored, although school food culture more broadly is now being inspected by OFSTED (Department for Education, 2023). Whilst there is a significant body of work discussing the implementation and evaluation of school food standards prior to 2011 (Nelson et al., 2012; Gray, 2008; Adamson et al., 2013; Evans et al., 2016), there have been no studies into the impact of the 2014 standards, or the experience of those tasked with delivering them.

Since deregulation in the 1980s when school meals services stopped being a statutory requirement, and competitive tendering for services was introduced, school meals services are also subject to market conditions and can provide an important revenue stream for schools (Devi et al., 2010). Current guidelines ask school governors to have a strategy for increasing meal uptake, although it does not specify to what level (Department for Education, 2023).

School food and public health nutrition

Existing policy, evaluation frameworks and academic research articles exploring school food in the UK prioritise issues of nutritional quality and uptake, often concluding that schools need to offer better food to support children and their families to make better choices (Department for Education, 2016; 2023). This assumes individualised behavioural drivers of action, an assumption that is challenged by social practice theorists, who offer an alternative account of complex social practices that evolve and capture (or lose) participants. An approach that offers insight into why policies often fail to make an impact on supposedly ‘bad’ choices (Shove, 2010).

School food provision is often tasked with addressing wider societal anxieties about healthy diets and is increasingly seen as an important ‘weapon’ in the ‘battle’ against childhood obesity (Illøkken et al., 2021; Adamson et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2006). This public health nutritional framing is not, however, one that is usually adopted by children at school dinner time, who often prioritise the social opportunities this break from classroom activity allows (Daniel and Gustafsson, 2010; Fletcher et al., 2014; Best, 2017). Nor does it acknowledge the primary concerns of many staff and parents, who will often prioritise children eating something or ‘enough’ at lunchtime over them eating a nutritionally balanced meal (Morrison, 1996; Harman and Capellini, 2015; Farthing, 2012). Moreover, there is very little evidence to support the effectiveness of these policies in reducing childhood obesity (Kelly and Barker, 2016; Ravikumar et al., 2022; Jaime and Lock, 2009; Van Cauwenberg et al., 2010). Whilst there is an assumption in policy that this is due to poor levels of uptake (Department for Education, 2023) the evidence that school based interventions result in long-term health improvements remains weak (Black et al., 2017). An evaluation of a free school meal pilot in the UK found that extended entitlement had little long-term impact on meal uptake or children’s diet or eating habits (Kitchen et al., 2010) and a study into food consumption trends in the UK concluded that the evidence that school food environments support healthy food choices in pupils is weak, identifying food system actors and food marketing as having a greater influence on food choices (D’Angelo et al., 2020).

There are tensions between policies tasked with improving health outcomes and the financial pressures that schools and school meal services face. This can result in kitchen staff turning to processed foods for convenience (Fernandes, 2013; Devi et al., 2010; Parnham et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2013). How school dinner operates as a social practice (including the ways in which space is used) is almost entirely subsumed by a nutritional discourse that dominates both policy and academic research in the UK. This is despite studies that show how important school lunchtime is for children and young people as a social event taking place in a social space (Briggs and Lake, 2011; Best, 2017, Morrison, 1996).

Assumptions about changing school meal practices and the implications for school kitchen design

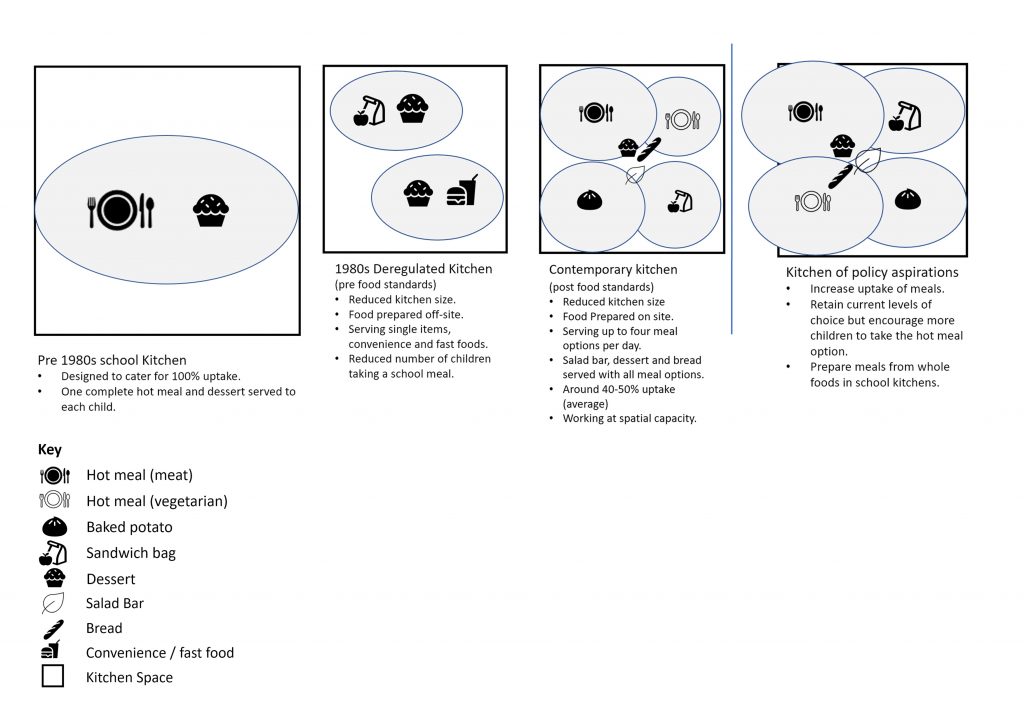

Since the introduction of a school meals service there have been significant changes in the assumptions about what a school lunch should constitute. When school meals became a statutory responsibility of LEAs in the 1940s, the norm was for a single hot food option to be provided at lunchtime, as well as a dessert that could be hot or cold. Lunches were to be prepared in school from raw ingredients which were stored on site (Walley, 1955). Children were served all components of the meal as standard (Evans, 2009; Rose et al., 2019). Following the deregulation of the school meal service in the UK during the 1980s, some local authorities moved away from full-service kitchens, with meals being prepared off site and delivered to schools to heat and serve. In addition to this and the removal of nutritional standards, the practice of allowing children to select and pay for individual items was introduced, allowing children to purchase items of convenience food to eat elsewhere or later in the day. This new format of food provision was much cheaper for individual schools than operating a full-service kitchen but led to a decline in meal quality and a reduction in uptake. In 2005 the celebrity chef Jamie Oliver made the decline in school food standards the focus of a television show and public campaign, and in response to this there was a return to full-service kitchens in school designs alongside the introduction of statutory nutritional standards for school meals served in state funded schools (Rose et al., 2019).

The introduction of school meal standards was not accompanied by a reversal of the practice of allowing children to make their own food choices. The norm for school meals currently is to offer a range of options each day from which children can choose. In the schools included in this study, a meat and vegetarian hot meal option was provided each day, as well as a jacket potato, a salad bar, a sandwich bag, a dessert, yoghurt, fresh fruit, and bread. This range of options is in line with national best practice guidelines (Dimbleby and Vincent, 2013; Department for Education, 2023) Despite this expansion in the range of meals being prepared, kitchen space allocation has reduced over time which is impacting upon the work of kitchen staff and their ability to meet school food policy aims, as will be discussed below.

The history of school building design

In the UK there was a resurgence of interest in the architecture of education in response to the building schools for the future (BSF) funding programme, which was announced by the then Labour government in 2004 (Mahony et al., 2011; Tse et al., 2015; Woolner, 2010). BSF was an ambitious programme that sought educational transformation through the rebuilding and refurbishing of all secondary schools in the UK using the then relatively new Public Finance Initiative (PFI) model of financing (Mahony and Hextall, 2013). In 2007 BSF was extended to select primary schools under the Primary Capital Programme. This significant investment, both financial and ideological, led to a new research interest related to school building design which included conferences, special editions and even the launch of a Master’s Degree in Educational Architecture at the University of Sheffield (Burke et al., 2010). This programme was one of the first things to be cut by the coalition government who came to power in 2010, and so this investment and interest in the impact of design on practice was short lived.

It is notable that even this renewed interest in the relationship between space design and practice failed to include school kitchens as spaces worth mentioning. When discussing the role that building design plays in the experiences of staff in schools, it does not recognise the work of the kitchen staff or discuss the environment in which this work takes place.

School kitchen design

Whilst literature about contemporary school kitchen design is rare, articles discussing institutional kitchen design can be found in Architectural journals in the 1950s, in response to the expansion of public catering in the post-war years and the new leisure trend of ‘dining out’ (Walley, 1955; Kitchen Design, 1957). These articles acknowledge the role that kitchen design plays in the work of institutional food provision and offer helpful insights into the assumptions about the kind of work that would take place in these kitchens and the format of school lunch service at the time, namely a single hot meal offer with dessert, served from a hatch to individuals or in batches to be served at table (known as ‘family service’). This information is derived from schematics showing kitchen layout, identifying areas dedicated to vegetable preparation and service counters. There is no detailed discussion about the work that takes place in these spaces.

Even the school food plan published in 2013, a document that provides detailed recommendations for improving the quality and uptake of school meals, does not mention kitchen design or space allocation. The recommendations for improving the work of kitchen staff focus upon improving training, providing certification, and raising the status of kitchen staff within the catering sector (Dimbleby and Vincent, 2013).

How school kitchens and dining spaces are designed now

Currently, the process for allocating space for school kitchens and dining rooms in the UK is to use the primary School schedule of accommodation tool provided by the UK government. (Department for Education, 2014). Kitchen spaces are classified differently to dining space in contemporary design guidance, with dining space described as ‘usable areas’ and kitchens as ‘supporting the functioning of the building’ (Department for Education, 2014). The minimum size for a full-service kitchen is now 30 m² + 0.08 m² for every pupil dining on site.

The size of the core preparation area will depend on the equipment needed, which in turn will depend on the type of preparation system to be used that ranges from traditional, through cook and chill to pre-prepared ‘fast food.’ (Department for Education, 2014)

The allocation of kitchen and food storage space is based upon a formula derived from the number of children in each age group within the school. When comparing the kitchen area for the production of 500 meals outlined in the 1955 Architecture journal with the space allocation for a school with 500 primary school pupils produced by the current schedule of accommodation toolkit, we see a reduction from 142m² in 1955 to 65m² using the current calculation for school kitchens. It is not clear in the contemporary design guidance why kitchen space has decreased so significantly over time.

There is currently more flexibility in the design and space allocation for dining halls as there is the option to utilise the main school hall as a dining room, as well as being able to use other supplementary circulation space such as corridors flexibly. Schools also have the option of running a staggered lunch break and using timed sittings to distribute the space and time pressure to serve and seat all pupils (Department for Education, 2014; School Food Plan, 2014).

Methodology

This paper reports upon findings from an Institutional Ethnography (IE) carried out in three UK primary schools between 2016 and 2019. The aim was to gain insights from school food workers about the relatively low uptake of school meals, and how this could be improved. School food workers accounts are missing from existing research into school food, and so making them the primary focus of this research addressed an empirical gap in knowledge as well as providing a critical new perspective from which to explore a policy problem.

IE is a qualitative research approach developed by Canadian Sociologist Dorothy Smith which seeks to discover the hidden working practices that shape the structures of everyday life (Smith, 2005). The methodology focuses upon how people interpret and apply messages about how work ‘should’ be done and how these interpretations lead to variation between the official account of the work and what happens in practice. This makes IE a useful research tool for exploring poor policy outcomes, such as the failure of improved school food policy to improve uptake and impact of school meals. Institutional Ethnography has been developed with the identification of hidden power structures as its primary function (Campbell and Gregor, 2008). Because IE blends epistemology, ontology, methodology and methods, it is not easy to summarise as a neatly replicable process (Murray, 2022). Campbell and Gregor (2008) provide an accessible and succinct introduction for those not familiar with IE, and Smith and Turner’s (2014) edited collection showcases a number of examples of how texts are used in IE. Murray (2022) provides an excellent paper exploring different approaches to textual analysis in IE, addressing some of the methodological ambiguity around how texts should and can be used in IE (Murray, 2022).

IE uses a range of common data gathering methods including semi and unstructured interviews, observation, work shadowing and content analysis. Research participants are classed as ‘expert informants’ who provide insights into working practices, and largely shape the direction of the research by suggesting ongoing points of enquiry. It uses each informant’s account to build a picture of the working practice rather than seeking to confirm ‘truths’ by triangulation of several accounts. IE was developed with the aim of exploring ‘ruling relations’ that exert themselves on everyday lives through institutional structures and texts.

IE is often used to reveal new perspectives within large organisations and the approach has been used in a number of contexts to explore both paid and unpaid work, including experiences of health and social care workers, the work that mothers do to support schools, the experience navigating academic conventions, and the work of managing chronic health conditions (Smith, 2005; De Vault, 2013; Lund, 2012; Smith and Turner, 2014). IE works with informants to map the work that they actually do and use this to explore the ways in which these lived experiences diverge from the more formalised account or dominant discourses of the work, especially when there are unanswered questions about why policies and processes are not having the desired outcome (Campbell and Gregor, 2008). It was appropriate for this research because it helped to challenge the dominant policy narrative that assumes that a healthy range of meal options will result in good levels of meal uptake (Department for Education, 2016; 2023) with insights from people doing the work about why policies were struggling to make an impact (Hawkins, forthcoming).

Texts in IE

A key aim of my work is to apply Institutional Ethnography’s conceptualisation of textual power to the study of a social practice. IE recognises texts as any ‘material objects that carry messages’ and crucially, that are replicable and so can be used by different people at different times to coordinate work process within an institutional context (Smith and Turner, 2014: p. 5). When a text enters the account of working practices it is said to have been activated. The analytical focus in IE is not the text itself, but rather the way that the actions of those who activate it are shaped and coordinated by their interpretation and application of the text (Smith and Turner, 2014) Texts are the carriers of the ‘ideological account’ of the work practice against which the lived experience can be compared (Smith, 2005). To give an example, the theme of this paper was identified through the mention of kitchen and dining space in interviews, and the observation of meal preparation and service. In interviews the process of designing new school buildings was mentioned in relation to changes in kitchen and dining spaces; this ‘activated’ the texts that are used in this process. As the interviewees couldn’t remember the specific details of these processes, I was directed to speak to a school architect to find out more about the design process, who explained the ways in which building design and schedule of accommodation texts discussed above were used to determine the space allocated to kitchens in new school buildings. The activation of these texts allowed me to explore the processes that were shaping the experiences of using space that kitchen staff had identified as significant. Once a text is activated the researcher looks for the ways in which the text relates to the coordination of work as described by the research informant. The analysis focuses not upon the detail of the text as a standalone object, but how it is shaping and coordinating working practices across a number of sites. Through this process I not only learned more about how space shaped practice, but I was also able to argue that the space issues that were experienced in both of the smaller and newer kitchens where being coordinated by the schedule of accommodation texts which were producing kitchen spaces that were smaller than they had previously been.

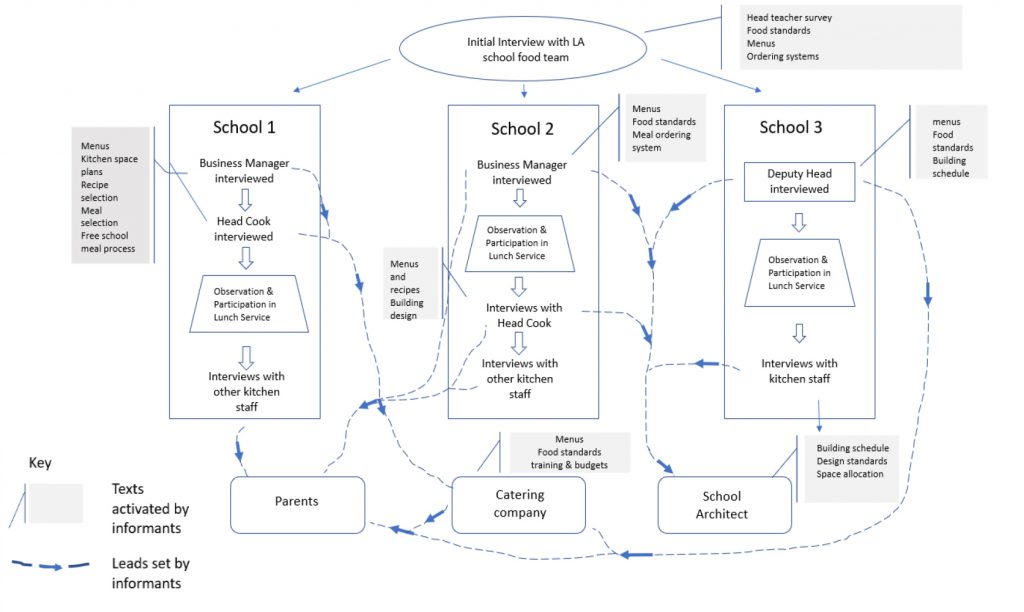

Because the focus of textual analysis in IE is in their role as coordinators of working practices, the role of the researcher is to map how the text coordinates work rather than carry out a detailed analysis of the text as a standalone object of research. Whilst there are many books and articles discussing the methodology and, in particular, how texts are incorporated and analysed in different contexts (Smith and Turner, 2014; Campbell and Gregor, 2008; Murray, 2022) in this research I was looking to show how certain texts were shaping work and how these were being interpreted and applied in different contexts. By showing these texts in process diagrams such as Figure 2, I hope to make visible these coordinating forces. My analysis of the text is centred on how research informants refer to it in the context of their work.

Sampling

I worked with three UK primary schools (pupils aged between 4-11) that were identified by a member of the local government school food team. School A had been built in the 1930s and schools B and C were less than ten years old and had been designed using the current space allocation guidelines (Department for Education, 2014) The schools were of a similar size (around 500 pupils) and were characterised by a similar demographic profile (around 50 per cent – 60 per cent of children in the schools were entitled to free school meals because their parents or carers were in receipt of means tested benefits). All three schools had a similar proportion of children choosing a school lunch (around 50 per cent), with the other 50 per cent bringing in packed lunches from home. All three kitchens had a head cook and between three and four supporting cooks.

Despite having similar demographic profiles, the schools had different approaches to school lunch service and different kitchen and dining spaces due to the age of the buildings. This sampling approach allowed a focus upon the differences in meal service rather than the ways in which different populations responded to the same food environment. The research was limited to three schools because of the resources and scope of the research project.

Data gathering

Following the leads set by research informants, I carried out fifteen semi-structured interviews. IE is interested in working practices and so interviewees were identified because of their roles and the ways in which their work contributed to the delivery of school food in the three schools. I carried out interviews with three school business managers or deputy heads (with lead responsibility for school food), three school head cooks, three kitchen support staff, the manager of the school catering company, a local authority school food officer, and a former school architect. Interviews followed a schedule but also made space for unstructured discussion, enabling themes to be explored flexibly and leaving space for the unanticipated to emerge (Savin-Baden and Howell Major, 2013). Research informants suggest the next point of enquiry, and so the number of interviews simply reflects the number of leads that were followed up during the time available to complete the project.

In addition to interviews, I worked with a number of ‘texts’ that were referenced by research informants during interviews or whilst being observed. The following texts were referenced by research informants.

- School menus.

- Nutritional standard guidance documents.

- School food policy documents.

- Schools web pages discussing school meal service.

- Design and build guidance for UK primary schools.

- Headteacher perception survey.

- Meal ordering systems.

- Stock management systems and forms.

- Free school meal allocation and management processes.

I also participated in school meal service and observed kitchen and dining working practices, making sketches and notes based upon my observations. A diagram of the data gathering process can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: How the data gathering process unfolded

Data analysis and presentation

IE is interested in how working practices are being shaped and coordinated by institutional power structures in the form of texts. Data analysis therefore focused upon mapping the connections between the different accounts to understand how working practices were being shaped. Notes, sketches and interview transcripts were coded to identify common themes and to capture references to texts as well as identifying other points of enquiry. Some of the themes identified related to the contents of the school lunch being unfamiliar to children, and parents being afraid of their children not eating the food. This was a significant theme and is covered elsewhere (Hawkins, forthcoming) as well as references to school food standards, policies, building design, time constraints and budget constraints. This analysis looked for ways in which the work was being coordinated by institutional processes and shaped by power structures, helping to build a ‘big picture’ of the working practices (Campbell and Gregor, 2008: p.85).

From the analysed data I produced narrative accounts from the perspective of different groups of informants, such as school kitchen staff and school managers. IE most commonly communicates findings using narrative accounts using the term ‘mapping’ conceptually rather than as a way of organising or visualising accounts (Murray, 2022). I wanted to develop the conceptual use of mapping into a more visual and accessible way of communicating findings (Hawkins, forthcoming) and so I applied a systems scribing approach to translate the accounts into systems maps. Systems scribing is a method for visualising the coordination of different accounts and borrows representative tools from system engineering, using elements such as actors, frames, relationships, and annotations to show dynamic systems and processes of change over time (Bird and Riehl, 2019). Elements of the system map are arranged and sized in order to show their relative power and relationship within the system based upon the accounts of informants and the observation of the practice. A deeper explanation of the system scribing approach is provided by Bird and Riehl (2019).

Findings

Findings are presented in two ways, firstly as a narrative summary of the key themes that emerged from the IE fieldwork with observations and quotations from research informants and secondly in process diagrams that show how changing policy processes can be seen to shape space allocation as well as the expectations about what a school meal service would provide, and subsequently how these influence working practices.

School kitchens are not big enough to meet the desired policy outcomes of increased demand

Of the three schools that participated in the IE, two reported issues with inadequate food storage and preparation space. Both schools B and C had been built as part of the Building Schools for the Future Primary Capital programme, and whilst many staff reported improvements in the quality of building spaces and equipment, kitchens had reportedly become much smaller than in previous buildings.

The impact of reduced kitchen space on meal provision was twofold. Staff reported that they had inadequate space to work and prepare the wide variety of meal options for the current uptake of school meals, which was between 40 per cent – 60 per cent of children enrolled at the school. With policies aiming to increase uptake of meals to improve child health and improve the financial viability of the school meal service (Department for Education, 2023), many staff were sceptical that they had the capacity to deliver on these targets within the current kitchen space. In one of the new school kitchens, staff reported that on the one day that many children stay for lunch, the annual Christmas meal, staff had to start the preparation the day before. Working some additional hours to support the Christmas lunch was an act of good from staff, but it highlighted the potential capacity issues and if uptake throughout the year reached these desired levels, this could not be sustained.

In school B, the head cook and kitchen staff had to share a small cupboard space used as a changing room, an office for menu planning and stock management, and for the storage of cleaning equipment and supplies. In school A that occupies an older building with generous kitchen space including a large and well-lit office, the head cook reflected that when she had started working in school food there were a lot more kitchen staff and more of the food was prepared from basic ingredients which took longer, whereas now they had access to more pre-prepared food and so needed fewer staff and less kitchen space. Whilst this wasn’t reported as a negative development, it does suggest that there is a tension between the school food policy objectives related to using minimally processed foods and preparing meals from fresh ingredients (Department for Education, 2014), and the resources provided to deliver these objectives.

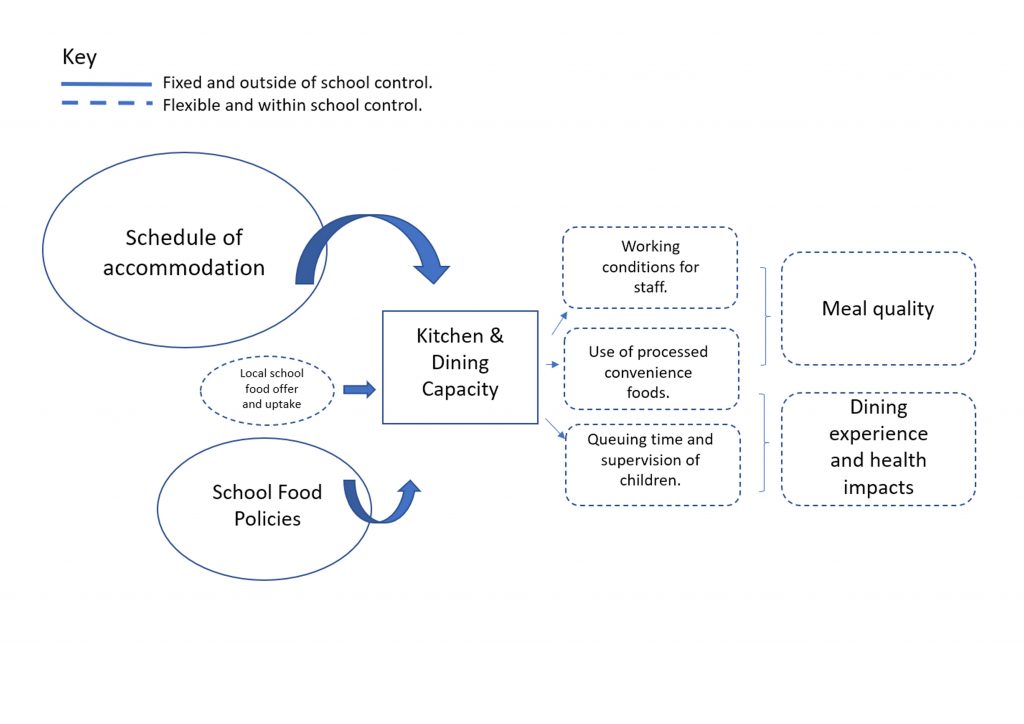

In the above example the accounts show how the work is being coordinated by the textual power (Smith and Turner, 2014) of the school food policies that target increased uptake (Department for Education, 2023), the school food standards legislation (UK Government, 2014); and the schedule of accommodation that determines kitchen size in newer school buildings (Department for Education, 2014).

School Kitchens don’t provide adequate storage space to meet expanded demand for school lunch or to support stock management

Providing a range of hot and cold meal options every day is a demanding and complex process, especially when many school cooks don’t receive the meal order until the morning of service. In addition to this, expanding the school food offer to include breakfast clubs, healthy snacks and cooking classes places demands upon the food storage and service space. Several school staff in schools B and C mentioned issues with storage and stock management due to limited kitchen space and so were unable to hold contingency stock and thus required to make frequent orders.

The kitchen on the other hand, is tiny. Probably a quarter of what they had at the other school. They have struggled with space, like even for stock, they don’t have space for holding stock which has been a real challenge for them, like when we had the snow days and couldn’t get delivery, they don’t hold the stock like they used to. You used to be able to have 20 tins of beans in the back for emergencies, but the cook just doesn’t have the space. (School C deputy head)

In school B the cook showed me how the supplies for the school breakfast club were now competing for space with the school lunch supplies, meaning she was only able to hold enough food for a few days’ worth of meals, increasing the amount of time she had to spend ordering stock (from her desk in the cupboard she shares with the cleaning supplies). This account directed the research to explore the processes that had led to smaller kitchens in the newer schools which ‘activated’ the schedule of accommodation texts (Department for Education, 2014).

Challenges over dining space allocation – dining hall space needs to be big enough for children to be supported to eat healthily

Dining space provision is another key area where different configurations of available space are shaping school meal practices. Current government guidance to schools (Department for Education, 2023) signposts to the schools to the school food plan ‘what works well’ web resource (School Food Plan, nd) which emphasises the importance of the lunchtime experience and the role of the lunchtime supervisors in supporting good food practices such as healthy eating, using utensils, and calm social interactions over lunch (School Food Plan, nd). This was another area where space constraints shaped practices in important ways that made it easier for schools with larger and more flexible dining spaces to meet the guidance.

Because all schools visited use a serving hatch system, where children queue for individual service, there is always a need to manage queuing times and availability of seating space.

In School A whilst the kitchen space was generous in comparison to the newer schools, the dining room space was much smaller, and this resulted in more pressure to move children through the space in the available time. In comparison, the two newer schools (B and C) had elected to either combine their dining and hall space allocation, or use their hall as the dining room, resulting in much larger dining areas and fewer time / space pressures.

In schools B and C which had larger dining rooms, staff were able to spend more time sitting with children, noticing when they weren’t eating and encouraging them to eat a healthy range of foods, this practice is in line with guidance provided to schools via the school food plan resource pack (School food plan, nd) in which lunchtime supervisors are told that their role includes encouraging pupils to eat a balanced meal and ‘manage pupil’s choices to ensure they get a balanced meal’ (LACA, 2015). In school A with less dining space this wasn’t happening, it was much busier and there was more pressure to finish up and move on. Very few staff were eating in the dining room and there was less circulation space for lunchtime supervisors to move around the table.

I heard lots of accounts from the serving staff about their strategies for encouraging children to take all elements of a balanced meal, but the real challenge came when the children sit down to eat, with many staff expressing frustration at how hard it was to get children to eat a healthy balanced meal. Time spent in the dining hall with children and creating a welcoming and relaxing atmosphere where dining together could foster valuable social interactions and develop social skills around dining was seen as crucial, but it was recognised that school design processes did not automatically prioritise space for this to happen and accordingly, compromises needed to be made.

School B had a small dining room space adjacent to the larger school hall, separated by folding doors. After trying to restrict the meal service to the allocated dining room, the school decided to open the doors at lunchtime and allow dining to take place in the hall space. It was reported that there was resistance to this from the caretaker who would have to ensure that the hall space was cleaned ready for the afternoon lessons, but they had been persuaded to take on this extra work for the sake of an improved lunchtime experience.

It’s just one hall too. We did have an option when we moved to this building to have a separate dining room, but we chose not to have one, but to have a cooking room instead. (School C Deputy Head)

The deputy head of school C explained that in the design of the new building they had the option of a very small separate dining space or providing a dedicated room for cooking lessons, and they chose to use the hall space for dining so as to provide this additional space. again, this meant that the school sports hall had to be transformed very quickly into a dining space and then returned to a clean and tidy space in time for lessons. These compromises are managed at a local level, but this process represents a lot of work and resourcing if schools are to be expected to deliver a holistic approach to healthy food.

These accounts show how the work of supervising children in order to ensure that they eat a balanced meal is work that is coordinated by the supervisor guidance texts (School Food Plan, nd; LACA, 2015) but shaped also by the schedule of accommodation processes (Department for Education, 2014) that determine whether there is adequate space in the dining room to move around the tables, or for staff to sit with children. In the case of dining room space, the newer school buildings were at an advantage, but only when they had decided to boost the space available for dining by combining it with the main hall space that was also used for sport and assemblies.

Queueing times, uncertain seating plans and the anxiety of busy lunchtimes

Queuing times are regularly cited as one of the reasons that children choose to take a packed lunch instead of a school meal. Long queues were reported to lead to disruptive behaviour and schools have well thought out strategies to manage lunchtime demand, often sending younger year groups in to eat first, letting the older children out to play and calling them in as the queue length diminishes. Queue length is partially determined by the space allocation in the dining room, but the main issue is the size and capacity of the serving hatch, combined with the range of dishes on offer and the ways in which children select their meals. Since deregulation and the introduction of choice, children now queue and choose from a selection rather than being served a single meal at table (Rose et al., 2019).

In most schools I visited children chose a meal in the morning and were allocated a coloured wrist band or sticker that the serving staff could use to identify what to serve them. Children would pass down a line, have their meal identified and then be served the relevant components, with some encouragement and negotiation taking place about which elements of the meal the children wanted and were required to take. Children then selected a dessert, bread and were then often directed to a self-serve salad bar. Getting nearly three hundred children aged between four and eleven through this process is a complex logistical challenge. In many cases these schools did not have spare time or space and so significantly expanding the number of children taking a school meal would represent a challenge. Currently children who bring in a packed lunch require seating space, but because they don’t need to be served, they take up far less time and don’t contribute to queuing pressures.

School space allocation – assumptions and expectations for school lunch

As the school design had been identified as a key issue by a number of research participants, I was directed to speak to a school building architect about their experiences of designing primary schools and look at the area guidelines and space allocation that were used in the design of primary school buildings at the time.

The school architect explained to me that the space allocation for kitchen space was a fixed formula calculated on the number of children in the school and the number of classes in each year group. This space allocation can be found in the scheduling documents for school buildings (Department for Education, 2014), but as with other elements of the school space allocation, it is not clear what assumptions about school lunch preparation work and food storage have informed these calculations.

There is a set formula, for example if you’ve got a two-form entry primary school you get a schedule of accommodation and a target maximum area. Dining areas have been getting smaller and smaller because they say there has been less take up of dinners. (School architect)

The school architect and one of the deputy headteachers who had been involved in the design process for their new school building confirmed that school dining space was seen as flexible space that could be traded for other specialist space provision within the school. The assumption was that other areas in the school, such as the hall could double up as dining space. As the kitchen and food storage sizes are fixed and non-negotiable, the spaces are clearly deemed adequate, and yet the people doing the work of school lunch delivery in these spaces tell me that they barely cope with the current low levels of demand, let alone being able to expand provision to meet policy aims which seek to increase the uptake of school meals whilst offering a range of healthy food options prepared on site (Department for Education, 2023).

Systems diagrams

Figure 2: Systems diagram showing the institutional and policy processes shaping school lunch practices and outcomes

Figure 2 brings together the accounts and observations from fieldwork with the findings from the analysis of texts activated by research participants, visualising this as a system. The most powerful force shown here is the schedule of accommodation, which sets the size of kitchens and dining spaces within which national and local school food policies must be enacted. Schools have no power to change national policies, but they do have some flexibility in how they respond to the pressures exerted by them. The message from school food workers who participated in this study is that any expansion in the uptake of school meals risks compromising meal quality and the dining experience.

Figure 3: How kitchen space and the school lunch offer have changed over time

Figure 3 shows in more detail how the divergence between school food policy and kitchen space allocation over time has created the pressures reported by school food workers, who are now expected to deliver a much more complex range of food options in significantly smaller spaces. Policy aspirations to increase uptake whilst maintaining choice do not appear to take into consideration the significant reduction in food preparation and storage space in the contemporary school kitchen.

Discussion

School food is tasked with supporting improvements in child health through the provision of meals in schools (Illøkken et al., 2021; Dimbleby and Vincent, 2013). These aims are ambitious in their scope and place a significant responsibility on the school meals service to deliver nutritionally balanced but also appealing food options that children and families will choose over packed lunches from home which have been found to contain a higher proportion of ultra-processed foods than school meals, and contain foods that would not be permitted under school food nutritional regulations (Parnham et al., 2022; Andersen et al., 2015). As well as delivering a range of healthy and appealing options, school food policy asks schools to have strategies in place to increase the uptake of school lunch (Department for Education, 2023). There are concerns about the lack of evidence that school food is having the desired impact because many children do not choose a school meal, and due to the prevalence of processed convenience food in the school food offer (Fernandes, 2013; Devi et al., 2010; Parnham et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 2013). School food nutritional policy seeks to improve these health impacts through increased uptake and meal quality, but to deliver on this school kitchens need to be able to meet increased demand for school meals, whilst minimising the use of processed foods, minimising food waste and staying within strict budgets (Dimbleby and Vincent, 2013; Department for Education, 2023).

Framing school lunch as a complex practice, this research has demonstrated how the work of providing school lunch has changed over time, and how this evolution has been shaped by changing institutional processes and policy that have exerted power upon the practice (Shove et al., 2012). My research makes a new contribution to knowledge by working from the accounts of school food workers to offer a new perspective on some of the barriers to policy delivery. These accounts have been largely absent from research into the delivery of school food policy, and they offer new insights into some of the challenges experienced when attempting to deliver policies at the front line. I have mapped institutional processes to show how power imbalances between competing policy areas (food policies and building design and space allocation policies) are shaping and constraining practices in school kitchens, adding a deeper level of explication to these accounts, and showing the textural processes that have led to the ‘problems’ encountered by people doing the work to meet policy aims (Smith and Turner, 2014).

School kitchen size has reduced over time as expectations about the work that would be done there shifted in line with changing ideological approaches to the provision of school meals, from a statutory duty to feed all children from a state-subsidised service to a deregulated free market model with no nutritional responsibilities (Rose et al., 2019). In recent decades there has been a gradual return to the original ideological framing of school food as vital to the health and wellbeing of children (Adamson et al., 2013; School Food Plan, 2014; Department for Education, 2023) but this has not been matched by increased resources. Spatially this can be seen as a shift from full-service kitchens designed to feed all children in the school a single hot meal option prepared from raw ingredients on site, to kitchens that are now half the size but serving up multiple meal options to a reduced number of children and struggling to work within the space and time allocated to the task. Schools want to increase uptake, but there are concerns that in newer buildings there isn’t the capacity to meet increased demand without compromising meal quality, or the working conditions of staff. School food work is still highly gendered and dominated by a female workforce. It has been argued that women ‘put up with’ working conditions and expectations and are willing to do extra work if the role demands it, or to balance work against other life commitments such as caring for families (Boterman and Bridge, 2015; Pilcher, 2000). This willingness to accept lower pay and more challenging working conditions in order to balance competing needs of employment and caring work can be seen as a structural segregation in the labour market (Bettio and Verashchagina, 2009). School food work has followed the pattern of public service restructuring which has exposed the predominantly female workforce to more job insecurity (Bell and Blanchflower, 2011; 2014). The willingness of kitchen staff and lunchtime supervisors to do additional work as an act of goodwill should be seen as potentially exploitative in this context.

School dining rooms also now need to incorporate space for queues, as children can no longer be served a single option at table and must queue and select from a wide range of options. Unsupervised children are known to make poor food choices (D’Angelo et al, 2020) so there is also significant work involved in ensuring they choose and then eat a healthy meal. This requires dining spaces where children can take their time to eat, and staff are able to supervise appropriately.

Conclusions and recommendations

This paper is not presenting a critique of school food policies, but rather arguing that there are spatial barriers to the effective delivery of policy aims. Tracking food policy alongside developments in school building design processes as set out in the Area guidance for Mainstreams Schools policy document (Department for Education, 2014), I argue that there has been a divergence between these two processes, and that food policy aims for increased meal uptake and freshly cooked meal options are not being reflected in the allocation of kitchen and food storage space. Kitchen staff are working at capacity in these spaces, and when they have to meet occasional spikes in demand (such as the annual Christmas dinner) staff have to work additional hours to meet this demand.

Older school buildings have much more generous kitchen and food storage spaces. This space was needed at the time of build because the expectation was that meals would be prepared daily from raw ingredients and that most children would take a school meal (Rose et al., 2019). School food policy and guidelines such as those issued by the Department for Education (2016; 2023) and the Food Foundation (2022) advocate for a return to the days of freshly cooked meals and increased uptake, but with the additional burden of having to provide a range of meal options. In modern school buildings there isn’t the space to store additional ingredients or to cook these additional meals.

Improving child health through the provision of school food is a complex issue with many factors determining success. This paper has focused upon one aspect of findings from a study in a limited number of schools which highlighted the spatial factors that were found to be shaping the way that school food work was taking place. In this context I argue that school building design needs to recognise the value and importance of this work and the role that space allocation plays in the delivery of school food policy, this could apply to the design of new buildings or the retrofitting older schools. School food workers involved in this research demonstrated a passion for the work and a commitment to improving the health and wellbeing of children by feeding them well. However, they are working within institutional constraints beyond their control and in spaces that do not seem to be designed to meet even current levels of demand, or that recognise the complexity of the practice.

I conclude by asking that policy makers value the experience of this committed and highly experienced workforce and make use of their knowledge in the policy design process. To that end I make the following recommendations:

- Policy makers should involve school food workers in school food policy design, with a particular emphasis upon their assessment of the resources needed to deliver changes in the school lunch offer.

- Reconnect school food policy makers, professional kitchen designers and school building designers to discuss the spatial implications of policy decisions connected to school food that make use of the expertise of school food workers.

- Policy makers should consider the work required to not only prepare the food, but to serve it and then encourage children to eat a balanced meal. This work becomes more complex with increased choice and has important spatial requirements.

Anna Hawkins, Department of the Natural and Built Environment, Sheffield Hallam University, S1 1WB. Email: A.hawkins@shu.ac.uk

Adamson, A., Spence, S., Reed, L., Conway, R., Palmer, A., Stewart, E., McBratney, J., Carter, L., Beattie, S. and Nelson, M. (2013) School food standards in the UK: Implementation and evaluation. Public Health Nutrition, 16, 6, 968-81. CrossRef link

Andersen, S.S., Holm, L. and Baarts, C. (2015) School meal sociality or lunch pack individualism? using an intervention study to compare the social impacts of school meals and packed lunches from home. Social Science Information, 54, 3, 394-416. CrossRef link

Batel, S., Castro, P., Devine-Wright, P. and Howarth, C. (2016) Developing a critical agenda to understand pro-environmental actions: contributions from Social Representations and Social Practices Theories. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Climate Change, 7, 5, 727–745. CrossRef link

Bell, D. and Blanchflower, D. (2011) Underemployment in the UK in the great recession. National Institute Economic Review, 215, R23. CrossRef link

Bell, D. and Blanchflower, D. (2014) Labour Market Slack in the UK. National Institute Economic Review, 229, 1, F4-F11. CrossRef link

Best, A. L. (2017) Fast food kids: French fries, lunch lines and social ties. New York: NYU Press.

Bettio, F. and Verashchagina, A. (2009) Gender Segregation in the Labour Market: Root Causes, Implications and Policy Responses in the EU. EU Expert Group on Gender and Employment (EGGE). Luxembourg: European Commission.

Bird, K. and Riehl, J. (2019) Systems Scribing; An Emerging Visual Practice. Available at: www.kelvybird.com [Accessed: 13/12/2022)

Black, A.P., D’Onise, K., McDermott, R., Vally, H. and O’Dea, K. (2017) How effective are family-based and institutional nutrition interventions in improving children’s diet and health? A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 17, 818. CrossRef link

Boterman, W.R. and Bridge, G. (2015) Gender, class and space in the field of parenthood: Comparing middle‐ class fractions in Amsterdam and London. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 40, 2, 249-261. CrossRef link

Briggs, L. and Lake, A.A. (2011) Exploring school and home food environments: Perceptions of 8-10-year-olds and their parents in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Public Health Nutrition, 14, 12, 2227-35. CrossRef link

Burke, C., Cunningham, P. and Grosvenor, I. (2010) Putting education in its place: Space, place and materialities in the history of education. History of Education, 39, 6, 677–680. CrossRef link

Cahill, C. (2007) The personal is political: Developing new subjectivities through participatory action research. Gender, Place & Culture, 14, 3, 267-292. CrossRef link

Campbell, M. and Gregor, F. (2002) Mapping social relations: A primer in doing institutional ethnography. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

D’Angelo, C., Gloinson, ER., Draper, A. and Guthrie, S. (2020) Food Consumption in the UK: Trends attitudes and drivers. Cambridge: The Rand Corporation. CrossRef link

Daniel, P. and Gustafsson, U. (2010) School lunches: Children’s services or children’s spaces? Oxfordshire: Abingdon. CrossRef link

Department for Education (2014) Area Guidelines for mainstream schools: BB103. London: Department for Education.

Department for Education (2016) School food in England: Departmental advice for governing boards. London: Department for Education.

Department for Education (2023) School Food: guidance for governors. London: Department for Education. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-food-standards-resources-for-schools/school-food-guidance-for-governors [Accessed: 15/04/23].

De Vault, M. (2013) Institutional Ethnography: A Feminist Sociology of Institutional Power [Review of Institutional Ethnography: A Feminist Sociology of Institutional Power]. Contemporary Sociology, 42, 3, 332–340. CrossRef link

Devi, A., Surender, R. and Rayner, M. (2010) Improving the food environment in UK schools: Policy opportunities and challenges. Journal of Public Health Policy, 31, 2, 212-226. CrossRef link

Dimbleby, H. and Vincent, J. (2013) The School Food Plan. Available at: http://www.schoolfoodplan.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/School_Food_Plan_2013.pdf [Accessed 09/02/2023].

Evans, C.E.L. and Harper, C.E. (2009) A history and review of school meal standards in the UK. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 22, 89-99. CrossRef link

Evans, C., Mandl, V., Christian, M. and Cade, J. (2016) Impact of school lunch type on nutritional quality of English children’s diets. Public Health Nutrition, 19, 1, 36-45. CrossRef link

Farthing, R. (2012) Going Hungry? Young People’s experiences of Free School Meals. London: Child Poverty Action Group. Available at: https://cpag.org.uk/policy-and-campaigns/report/going-hungry-young-peoples-experience-free-school-meals [Accessed: 01/02/2023].

Fernandes, M.M. (2013) A national evaluation of the impact of state policies on competitive foods in schools. Journal of School Health, 83, 4, 249-255. CrossRef link

Fletcher, A., Jamal, F., Fitzgerald-Yau, N. and Bonell, C. (2014) ‘We’ve got some underground business selling junk food’: Qualitative evidence of the unintended effects of English school food policies. Sociology, 48, 3, 500-517. CrossRef link

Food Foundation (2022) The Superpowers of Free School Meals: an evidence pack. Available at: https://foodfoundation.org.uk/publication/superpowers-free-school-meals-evidence-pack [Accessed: 15/05/23].

Giddens, A. (1984) The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity Press.

Gray, J. (2008) Implementation of school food standards in England – a catering perspective. Nutrition Bulletin, 33, 3, 240-244. CrossRef link

Harman, V. and Cappellini, B. (2015) Mothers on display: Lunchboxes, social class and moral accountability. Sociology, 49, 4, 764-781. CrossRef link

Hawkins, A (Forthcoming) Mapping Working Practices as Systems: An analytical model for visualising findings from an Institutional Ethnography. Qualitative Research.

Hawkins, A. and Rundle, R. (Forthcoming) School Food Hero and the Battle of the Food Foes: a story of public health policy, power imbalance and potential. Social Science and Medicine.

Illøkken, K.E., Johannessen, B., Barker, M.E., Hardy-Johnson, P., Øverby, N.C. and Vik, F. N. (2021) Free school meals as an opportunity to target social equality, healthy eating, and school functioning: experiences from students and teachers in Norway. Food & Nutrition Research, 65, 1–13. CrossRef link

Impact on Urban Health (2022) Cost benefit analysis of free school meal provision expansion. Available at: https://urbanhealth.org.uk/insights/reports/expanding-free-school-meals-a-cost-benefit-analysis [Accessed: 07/03/23].

Jaime, P. C. and Lock, K. (2009) Do school based food and nutrition policies improve diet and reduce obesity? Preventive Medicine, 48, 1, 45-53. CrossRef link

Kelly, M.P. and Barker, M. (2016) Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health, 136, 109–116. CrossRef link

Kesby, M. (2007) Spatialising participatory approaches: The contribution of geography to a mature debate (report). Environment & Planning A, 39, 12, 2813-2831. CrossRef link

Kitchen, S., Tanner, E., Brown, V., Payne, C., Crawford, C., Dearden, L., Greaves, E. and Purdon, S. (2010) Evaluation of the Free School Meals Pilot: Impact Report. Department for Education Research Report DFE-RR227. London: Department for Education.

LACA (2015) A professional standard for a midday supervisor. Available at: http://whatworkswell.schoolfoodplan.com/site/article-files/5c8866e7-9964-49fa-9365-7fa04ac79e3c.pdf [Accessed: 14/08/2023].

Lund, R. (2012) Publishing to become an “ideal academic”: An institutional ethnography and a feminist critique. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 28, 3, 218-228. CrossRef link

Mahony, P. and Hextall, I. (2013) “Building Schools for the Future”: “transformation” for social justice or expensive blunder? British Educational Research Journal, 39, 5, 853–871. CrossRef link

Mahony, P., Hextall, I. and Richardson, M. (2011) “Building Schools for the Future”: reflections on a new social architecture. Journal of Education Policy, 26, 3, 341–360. CrossRef link

Mazarello, V., Ong, K. and Lakshman, R (2015) Factors influencing obesogenic dietary intake in young children (0-6): Systematic review of qualitative evidence. BMJ Open, 5, 9. CrossRef link

Morrison, M. (1996) Sharing food at home and school: Perspectives on commensality. The Sociological Review, 44, 4, 648-674. CrossRef link

Murray, O.M. (2022) Text, process, discourse: doing feminist text analysis in institutional ethnography. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 25, 1, 45-57. CrossRef link

Nelson, M., Nicholas, J., Riley, K. and Wood, L. (2012) Seventh annual survey of take up of school lunches in England. Children’s Food Trust. Www.Childrensfoodtrust.Org.uk/assets/research-reports/seventh_annual_survey2011-2012_full_report.Pdf [Accessed: 14/05/2017].

Nelson, M., Nicholas, J., Suleiman, S., Davies, O., Prior, G., Hall, L., Wreford, S. and Poulter, J. (2006) School meals in primary schools in England. Research Report No. RR753. Nottingham: DfES Publications.

Parnham, J.C., Chang, K., Rauber, F., Levy, R. B., Millett, C., Laverty, A. A., Stephanie von Hinke, and Vamos, E.P. (2022) The Ultra-Processed Food Content of School Meals and Packed Lunches in the United Kingdom. Nutrients, 14, 14, 2961. CrossRef link

Pilcher, J. (2000) Domestic Divisions of Labour in the Twentieth Century: Change Slow A-Coming. Work, Employment and Society, 14, 771-780. CrossRef link

Ravikumar, D., Spyreli, E., Woodside, J., McKinley, M. and Kelly, C. (2022) Parental perceptions of the food environment and their influence on food decisions among low-income families: a rapid review of qualitative evidence. BMC Public Health, 22, 1, 9-9. CrossRef link

Rose, K., Lake, A.A., Ells, L.J. and Brown, L. (2019) School food provision in England: A historical journey. Nutrition Bulletin, 44, 3, 283–291. CrossRef link

Savin-Baden, M. and Howell Major, C. (2013) Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice. London: Routledge.

School Food Plan (2014) School food standards: A practical guide for schools, their cooks and caterers. (Guidance). London: Department for Education.

School Food Plan (2014) What Works Well. Available at: http://whatworkswell.schoolfoodplan.com/ [Accessed: 14/08/2023].

Shove, E. (2010) Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environment and Planning A, 42, 6, 1273-1285. CrossRef link

Shove, E., Pantzar, M. and Watson, M. (2012) The dynamics of social practice everyday life and how it changes. London: SAGE. CrossRef link

Smith, D.E. (2005) Institutional ethnography: A sociology for people. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

Smith, D.E. (2008) From the 14th floor to the sidewalk: Writing sociology at ground level. Sociological Inquiry, 78, 3, 417-422. CrossRef link

Smith, D.E. and Turner, S.M. (Eds.) (2014) Incorporating texts into institutional ethnography. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. CrossRef link

Stevens, L., Nicholas, J., Wood L. and Nelson, M. (2013) School lunches v. packed lunches: a comparison of secondary schools in England following the introduction of compulsory school food standards. Public Health Nutrition 16, 6, 1037-1042. CrossRef link

The Gas Council (1957) Kitchen Design: Schools, Hospitals, Factories, Hotels, Restaurants and Cafés. Architects’ Journal (London), 126, 3275, 16–17.

Tse, H.M., Learoyd-Smith, S., Stables, A. and Daniels, H. (2015) Continuity and conflict in school design: a case study from Building Schools for the Future. Intelligent Buildings International, 7, 2-3, 64–82. CrossRef link

UK Government (2014) The requirements for school food regulation 2014. (Statutory Legislation). London: UK Government.

UNISON (2005) School Meals, Markets and Quality. London: UNISON.

Van Cauwenberg, E., Maes, L., Spittaels, H., van Lenthe, F.J., Brug, J., Oppert, J. and De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2010) Effectiveness of school-based interventions in Europe to promote healthy nutrition in children and adolescents: Systematic review of published and ‘grey’ literature. British Journal of Nutrition, 103, 6, 781-797. CrossRef link

Vihalemm, T., Keller, M. and Kiisel, M. (2015) From intervention to social change: A guide to reshaping everyday practices. Ashgate. CrossRef link

Walley, JE., (1955) Technical section: 10 design: building types design of school kitchens. Architects’ Journal (London), 121, 3140, 615–618.

Watson, M. (2014) Placing power in practice theory – A DEMAND centre working paper. Unpublished manuscript.

Weis, L. and Fine, M. (2012) Critical bifocality and circuits of privilege: Expanding critical ethnographic theory and design. Harvard Educational Review, 82, 2, 173-201. CrossRef link

Woolner, P. (2010) The design of learning spaces. London: Continuum.