Abstract

Across the world we are witnessing increased infringements on the right to protest, in both democratic and authoritarian countries. The academic literature on governments’ anti-protest policies consists predominately of legal and sociological perspectives, emphasising breaches of human and civil rights. Others discuss the ethicality of protesters’ methods, such as vandalising public property and blocking public highways. Contributions to these discussions from the field of Security Studies, a sub-discipline of International Relations, are essentially absent. However, by engaging with contemporary theoretical developments, Security Studies can complement the existing discussion by offering meaningful critiques of governments’ anti-protest policies. At the same time, the study of protests through the lens of Security Studies offers a fruitful conceptual space for the development of new ideas of security, such as the concept of protest strand securitization presented in this article.

Introduction

Across the world we are witnessing increased infringements on the right to protest, in both democratic and authoritarian countries. The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) crackdown against pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong resulted in mass-arrests and thousands of casualties among the protesters (Maizland & Fong, 2024). In the USA, instances of police brutality in response to the Black Lives Matter protests have been described by Amnesty International (2020) as a breach of human rights and dignity. In the UK, former Prime Minister Rishi Sunak referred to protests as a type of ‘mob rule’ undermining British democracy (McKiernan & Faulkner, 2024). This prompted civil rights groups to accuse the UK government of demonising and censoring the people’s right to protest (Grierson, 2024).

The academic literature on governments’ anti-protest policies consists predominately of legal and sociological perspectives, emphasising breaches of human and civil rights (see Feldman, 2023; Wall, 2023). Others discuss the ethicality of protesters’ methods, such as vandalising public property and blocking public highways (see Panlee, 2021; Pesarini & Panico, 2021). Contributions to these discussions from the field of Security Studies, a sub-discipline of International Relations, are essentially absent. Moreover, the academic literature is generally critical of security-based perspectives regarding the right to protest (see Moss, 2022; Wall, 2023), because security is often invoked to frame protest as a source of social unrest and thus are used to justify anti-protest policies. For example, in the UK, the former Conservative Government’s MPs’ anti-protest rhetoric has been accompanied by calls for additional funding for greater security measures, including increased police powers (see Maizland & Fong, 2024; Grierson, 2024).

However, by engaging with contemporary theoretical developments, Security Studies can complement the existing discussion by offering meaningful critiques of governments’ anti-protest policies. At the same time, applying the theoretical perspectives of Security Studies to the study of protests and anti-protest policies offers a conceptual space to develop existing security perspectives. In this article, I offer a critique of anti-protest policies from a Security Studies perspective, while also showcasing a theoretical development to Securitization Theory illustrated through the insights achieved from studying protest.

I present the concept of protest strand securitization, which outlines the mechanics by which disempowered groups voice their security concerns through the medium of protest. Using this concept, I levy a Security Studies critique which highlights that, by posing a barrier to disempowered communities voicing their security concerns, anti-protest policies compound civil inequalities while paradoxically making social unrest more likely.

This article proceeds in three sections. The first outlines Securitization Theory, which considers how security issues are socially constructed, as well as the strands of securitization concept, which details specific socio-political securitization mechanics. The second section then presents the protest strand, a new theoretical development of Securitization Theory which considers the specific securitization mechanics of protests related to perceived security issues. This is done with a focus on Chinese protests. The applicability of the concept in other socio-cultural contexts is indicated through briefer preliminary and illustrative examples. The final section considers the significance of the protest strand, using it to contribute to existing critiques of anti-protest policies and offering a Security Studies interpretation of anti-protest policies being more likely to trigger social unrest than prevent it.

Securitization theory

An issue comes to be considered a security threat through a socio-political process referred to as securitization. Securitization Theory explains that securitization occurs when a securitizing actor (usually a social elite) makes a securitizing move in the form of a speech act, invoking their community’s values and ideals to present an issue as a security threat to a referent object, the thing to be protected (Buzan et al., 1998). The audience of the securitizing move can either accept or reject the securitization (Buzan et al., 1998).

Securitization Theory explains that when a community accepts an issue as a security threat, it is considered an existential threat to said community that justifies exceptional measures in its address (Buzan et al., 1998). For a nation-state, this could mean declaring war or restricting individual freedoms. However, securitization can also occur at a sub-state level (Buzan et al., 1998), with groups securitizing perceived threats to their sub-state community as security issues, motivating exceptional behaviours outside of the day-to-day, such as engaging in protest.

One example of a domestic securitizing move is former UK prime minster Boris Johnson’s 2020 announcement of lockdown restrictions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It presented COVID-19 as an existential threat to the British people and the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) which justified the exceptional measures of increased health spending, restrictions of people’s movements and shutting down areas of the economy (Eves & Thedham, 2020). More recently, securitization mechanics can be seen in the rhetoric of speech acts conducted regarding the right to protest. For example, Sunak’s framing of protests as ‘mob rule’ that threatens British democratic values, was used to justify additional security measures in the form of new policing powers to control and deter protests (McKiernan & Faulkner, 2024).

Strands of securitization

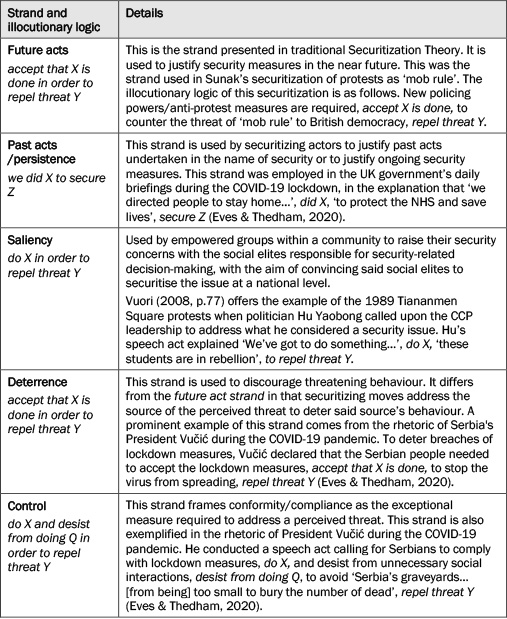

Vuori (2008; 2011) provides more detail on the social mechanics of securitization through their strands of securitization concept. This concept explores the blurring of politics and security, outlining how securitizing mechanics differ depending on the socio-political objectives of the securitizing actor. Vuori (2008; 2011) presents five strands of securitization and argues that traditional securitization only considers the future act strand, but that a community will have preferences for different strands depending on their political culture. Each strand has its own illocutionary logic, the way a request is made of the audience. Vuori’s strand concept offers a framework with which to consider how different communities and groups engage with the securitization process, providing a tool with which to undertake a security-based analysis of protests. The five strands of securitization identified by Vuori are presented in the table below.

With this in mind, applying the strands of securitization concept to examples of political protest in which protesters are voicing security concerns reveals clear securitization mechanics, but also an illocutionary logic distinct from the strands identified by Vuori. Vuori (2008; 2011) explains that there are likely more strands of securitization than the five they outlined, leading to the conclusion that security-related protests employ a distinctive protest strand of securitization.

Protest strand securitization

The protest strand is outlined in this section using the example of the large-scale anti-Japanese protests that occurred in China in 2012. This example is given because it is consistent with Vuori’s (2011) presentation of the original five strands, which were also first identified and presented in the study of Chinese securitizing moves.

In September 2012, mass-protests erupted across China following Japan’s nationalisation of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea, an island-chain administered by Japan but claimed by China. Tens-of-thousands of Chinese protesters gathered outside of the Japanese embassy in Beijing and in over 100 cities across China (Green et al., 2017).

While these were nominally anti-Japanese protests, many protesters used the cover of nationalistic anti-Japanese protests as an opportunity to also protest the CCP’s regime. The CCP’s 2012 leadership contest brought to the surface party infighting and corruption scandals (Hall, 2019). This triggered growing discontent with the political status quo in China, especially after Bo Xilai, a frontrunner to lead the CCP and the preferred candidate of then-president Hu Jintao, was implicated in a murder scandal (Wines, 2012). Within the anti-Japanese protests prompted by Japan’s nationalisation of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, there was a sizeable contingent of protesters calling for an end to corruption and even democratic reforms (Buckley, 2012). To this end, the protests should be considered an effort to raise security concerns about the perceived failings of the Chinese government, triggered by the apparent weakness of what they believed to be a corrupt government in the face of Japanese provocation (Hafeez, 2015).

With this context in mind, the distinctive illocutionary logic of the protests’ securitizing mechanics is evident in two examples of protester rhetoric. The first is typical of the rhetoric of protesters gathered outside the Japanese embassy in Beijing:

Mao is our hero because he fought the Japanese and won… Our leaders today talk only of peaceful diplomacy and look what happened. They are giving away our land. (cited in Buckley, 2012).

The reference to Mao Zedong is significant. Mao, who led an army against Japan during World War II and led China following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 until his death in the 1970s, is generally considered in China to have been a moral and effective leader of the Chinese nation (Mitter, 2013).

The second example is more typical of the pro-democracy elements among the anti-Japanese protesters:

We think that the government is too soft and we want to show what we think… China should make its own demands as a great power. I feel disappointed in the government. It’s not democratic enough and doesn’t heed our voice. I hope our leaders can catch up. There’s no conflict between democracy and patriotism. (cited in Buckley, 2012).

In the first example, the protesters’ illocutionary logic was: be like Mao and fight the Japanese, do X, peaceful diplomacy is failing China, threat Y, and due to which China is losing its land, warning Q. In the second, pro-democracy example, the illocutionary logic was: our leadership is too weak, threat Y, it needs to listen to the people, do X, otherwise democracy, warning Q.

This illocutionary logic, do X to repel threat Y otherwise warning Q, is unique as it does not align with any of the pre-established strands. Yet, there is overlap in characteristics between the illocutionary logic expressed in these speech acts and that of the saliency, deterrence, and control strands. The overlap with the saliency strand is straightforward. The protesters sought to raise the saliency of their concerns about their country’s leadership, hence the calls upon the CCP to be more like Mao. The overlap with the deterrence strand is found in how the audience of the speech acts was the CCP, the source of the perceived threat of weak leadership and how the protesters were attempting to deter further weakness. The overlap with the control strand is found in the Q element of the illocutionary logic. Of all the pre-established strands, only the control strand issues a warning to desist from Q. However, the protesters’ speech acts evidently issued a warning.

The protesters’ illocutionary logic speaks to a distinct protest strand of securitization, situated in the confluence of the saliency, deterrence and control strands. The protest strand is the strand of securitization employed by disempowered groups (the securitizing actors, in this case protesters disempowered by corruption and perceived government weakness) raising their security concerns with societal elites (the CCP). The securitizing actors call upon these social elites to act to address the group’s insecurity while demanding the cessation of behaviours that disregard the group’s interests and wellbeing, threatening further action if the group’s security concerns are ignored. The protest strand’s bottom-up form of securitization led by disempowered groups is significant. Due to the focus on social elites as securitizing actors (Buzan et al., 1998), traditional Securitization Theory is usually a top-down social process in which disempowered groups have relatively little agency.

The characteristics of the protest strand can also be observed in protests outside of China. For example, the #EndSARS protests in Nigeria, in which young Nigerians called for an end to police brutality, particularly that of the notoriously abusive Special Anti-Robber Squad (SARS), accompanied by the threat of social unrest (see Malumfashi, 2020; Fasakin 2022).

Among chants and placards calling for an end to police brutality, a speech act by a leading protester explained: “We are determined to continue these protests until justice is served. (cited in Malumfashi, 2020)

In this example, the illocutionary logic is ‘end police brutality’, repel threat Y, ‘we are determined to continue these protests’, warning Q, unless ‘justice is served’, do X.

The presence of protest strand mechanics in both China and Nigeria indicates that the use of the protest strand by disempowered groups to raise security concerns through the medium of protest is fairly common. This conclusion is reinforced considering the multitude of protests which serve as potential examples of protest securitization from countries around the world. Other preliminary examples in which protest strand mechanics may be present include the Black Lives Matter protests in the USA following the murder of George Floyd and the vigils held in the UK following the murder of Sarah Everard. Both of these cases align to the core indicators of protest strand secuitization, traditionally disempowered groups raising their security concerns through the medium of protest, calling for social elites to stop ignoring their plight with the threat of further protests if this continues (see Silverstein, 2021; Young, 2021; Ambrose, 2022).

More research is needed to better establish and understand the protest strand in the examples discussed above. This is particularly the case given that the differing cultural and social contexts of these protests will affect how the protest strand and its mechanics manifest. Comparative studies of likely examples of protest strand securitization should help to isolate the protest strand’s mechanics separate from culturally specific variables.

Why does the Protest Strand matter?

Understanding protest as a medium for disempowered groups to raise their security concerns through a distinctive protest strand of securitization is significant for several reasons. The concept of protest strand securitization can offer insights into how protest is used to establish a platform to perform speech acts with a distinctive illocutionary style. Meanwhile, given that protesting is a political act, identifying the specific securitizing mechanics of how protesters engage in securitization helps to explore the blurred line between the realms of politics and security. However, more significant is that the protest strand offers a link between Security Studies and the debate about government’s anti-protest policies. Using this link, Security Studies is able to support existing critiques of anti-protest policies and contribute its own critiques of growing infringements on the right to protest.

Supporting existing critiques

As stated in the introduction, the academic literature on anti-protest policies focuses on human and civil rights narratives regarding the right to protest (see Feldman, 2023; Wall, 2023). By way of the protest strand, Security Studies contributes to this narrative.

Securitization is a societal process in which different communities in a given society engage to voice and shape their overarching security agenda. If protest is a means through which disempowered groups engage in securitization processes, then anti-protest policies raise a barrier to this aspect of civic participation. This is the case because, at least indirectly, anti-protest policies are criminalising the means through which already disempowered people engage in the societal process of securitization and, by extension, criminalising the capability and capacity of disempowered communities to shape their society’s security agenda.

An example of this is the UK 2023 Public Order Act. This Act de facto labels peacefully disruptive protest a serious crime that justifies potentially discriminatory policing powers like suspicion-less stop-and-search (Evans, 2023). Evidence demonstrates that stop-and-search is disproportionately employed against people of colour (Byrne, 2020). The over-policing of these communities using these powers has historically sown mistrust of the police as it is a key example of over-policing as a civil rights issue for communities of colour in the UK (Evans, 2023).

In addition to this established understanding of over-policing as a civil rights issue, increased police power as an anti-protest measure poses an additional barrier to civic participation. Anti-protest policies like the Public Order Act 2023 may deter traditionally disempowered groups in the UK from participating in societal securitizing processes. In doing so, anti-protest policies further suppress disempowered voices in society and the realm of security policy decision-making specifically.

A security studies critique

Through the protest strand, Security Studies is also able to levy its own critiques of anti-protest policies. Namely, anti-protest policies fail to recognise the role of protest as a medium of voicing security concerns, and thus paradoxically, are likely to trigger the social unrest that they were meant to mitigate.

As mentioned, sub-state groups engaging in security-related protests have likely already securitized the perceived threat to justify exceptional measures outside of their day-to-day behaviour, such as engaging in protest. Accordingly, further exceptional measures, such as escalating protests into instances of social unrest, may also be considered justified if authorities engage in anti-protest measures. The protesters may have already stated such in the warning Q component of their illocutionary logic.

An example of this can be observed in China’s 2012 anti-Japanese protests. The CCP, likely eager to avoid tensions with Japan, ignored the protesters and their demands in the earlier phases of the protests (Branigan, 2012). To overcome this barrier, the protests in the city of Shenzen escalated from peaceful demonstrations into social unrest, including a large group of protesters storming a CCP office building (Wallace et al, 2015). Unrest in other cities included hundreds of protesters rushing police lines outside of Japanese owned buildings, including the Japanese embassy in Beijing, and the destruction of private and public property (Wee & Duncan, 2012).

In hindsight, this escalation is unsurprising due to the illocutionary logic of the protest strand, which warns social elites of further action should the protesters’ security concerns be ignored. If disempowered groups believe an escalation of their actions is justified in the face of barriers to their securitizing move and thus protesters’ warning of further action are sincere, it highlights a major flaw in anti-protest policies. This flaw is that rather than discouraging social unrest, by presenting a barrier to overcome while essentially ignoring protesters’ warnings of further action, anti-protest policies seeking to mitigate social unrest are making social unrest more likely.

This can also be clearly observed in the actions, and the repercussions of said actions, taken by Chinese protesters in 2020. Chinese nationalist groups had been organising to voice concerns that the CCP were not doing enough to counter international condemnation of the crackdown on Hong Kong. Feeling the CCP was too slow to act on, and was even discouraging of their voicing of, their concerns (Eves, 2024), one hacktivist groups hijacked the Twitter account of the Chinese embassy in Paris. In doing so, they escalated international tensions by weaponising the Chinese state’s diplomatic infrastructure, posting images that depicted the USA as the personification of death, trailing blood as it arrived at Hong Kong (Keyzer, 2020). In this escalation, the hacktivists compounded the pressures on the CCP by forcing a diplomatic incident that the CCP had to resolve, while also having to manage the domestic political pressures and fear of unrest arising from increasingly disgruntled nationalist groups (Eves, 2024). In this example, ignoring the protesters concerns evidently caused greater issues for the CCP than might have been if they’d engaged with the protesters earlier on. This showcases the paradox of anti-protest policies as they can escalate matters and lead to the unrest and insecurity that the anti-protest policies sought to avoid.

Conclusion

Security Studies has a meaningful contribution to make to the growing academic literature on anti-protest policies. Through the concept of protest strand securitization, it is possible to understand protest as a medium through which disempowered communities voice their security concerns to social elites.

With this in mind, Security Studies is able to support existing critiques of anti-protest policies, highlighting how presenting a barrier to securitizing protests compounds existing civil inequalities. At the same time, an additional critique can be levied that anti-protest policies aimed at maintaining security by discouraging social unrest paradoxically pose a possible trigger for social unrest, in accordance with the warnings issued by protesting groups.

As a concept, protest strand securitization is in its infancy and requires further research to better establish its exact securitization mechanics. This could be achieved through the application of the concept to other historical examples of protest. This would help establish other case studies in which protest strand securitization was present. This, in turn, would allow for comparative studies of instances in which protests invoked the protest strand, enabling a better understanding of what the protest strand is and the implications of anti-protest policies that present barriers to protest strand securitizations.

Once protest strand securitization is better understood and established, there will likely be opportunities for further research on protest, policy and security. For example, exploring what a successful protest strand securitization looks like in terms of media coverage, policy outcomes and long-term social effects. It may also be possible to research the effectiveness of anti-protest policies in terms of how they disrupt the mechanics of protest strand securitization to supress social movements. Given the existence of protest strand securitization, research could explore notions of protest de-securitization, considering how acts of protest may help to move an issue from being treated as a security issue to a political issue. Alternatively, research could be undertaken to understand the role of the protest strand in counter-protests and whether it is possible for opposing groups of protesters to portray one another as security threats through invocation of the protest strand. Another avenue of research could be to understand how the protest strand is invoked in less verbal forms of protest, such as digital activism and acts of non-violent resistance. Each of these suggestions for future research would further prove the benefit of Security Studies in contribution to the ongoing discussion and critique of anti-protest policies.

*Correspondence address: Lewis Eves, Sheffield Hallam University, Howard St, Sheffield City Centre, Sheffield, S1 1WB. Email: Lewis.eves@shu.ac.uk

Ambrose, T. (2022, June 17). Met Officers ‘feared Sarah Everard vigil had become anti-police protest’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/jun/07/met-officers-feared-sarah-everard-vigil-had-become-anti-police-protest

Amnesty International (2020, August 4). USA: Law enforcement violated Black Lives Matter protesters’ human rights, documents acts of police violence and excessive Force. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2020/08/usa-law-enforcement-violated-black-lives-matter-protesters-human-rights/#:~:text=Today%2C%20Amnesty%20International%20USA%20released,in%20May%20and%20June%20of

Branigan, T. (2012, September 19). Japan’s purchase of disputed islands is a farce, says China’s next leader. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/sep/19/china-japan-senkaku-diaoyu-islands

Buckley, C. (2012, September 19). Analysis: Chinese Leaders may come to Regret Anti-Japanese Protests. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-japan-politics-idUSBRE88I0AU20120919

Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A New Framework For Analysis: USA, Lynne Rienner Publishers. CrossRef link

Byrne, B. (2020). Ethnicity, Race and Inequality in the UK. Bristol: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Evans, C. (2023). The Public Order Act 2023: Has our right to protest been restricted? Saunders Law. https://www.saunders.co.uk/news/the-public-order-act-2023-has-our-right-to-protest-been-restricted/#:~:text=Vague%20and%20widely%20defined%20powers,powers%20against%20ethnic%20minority%20communities

Eves, L., & Thedham, J. (2020, May 14th). Applying Securitization’s Second Generation To COVID-19. E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2020/05/14/applying-securitizations-second-generation-to-covid-19/

Eves, L. (2024). Antagonistic Symbiosis: The Social Construction of China’s Foreign Policy. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 65(1), pp. 123-129. CrossRef link

Fasakin, A. (2022). Subaltern Securitization: The Use of Protest and Violence in Postcolonial Nigeria. Stockholm Studies in International Relations, 2, pp.1-256. https://su.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1615896&dswid=3570

Feldman, D. (2023). The growing complexity of human right to assemble and protest peacefully in the United Kingdom. Victoria University of Wellington Law Review, 54(1), pp. 155-182. CrossRef link

Green, M., Hicks, K., Cooper, Z., Schaus, J., & Douglas, J. (2017, June 14). Counter Coercion Series: Senkaku Islands Nationalization Crisis. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. https://amti.csis.org/counter-co-senkaku-nationalization/

Grierson, J. (2024, March 8). Open letter to Sunak condemns ‘crackdown’ on right to protest. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/mar/08/open-letter-to-rishi-sunak-condemns-crackdown-right-to-protest-amnesty

Hafeez, S.Y. (2015). The Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands Crises of 2004, 2010, and 2012: A Study of Japanese-Chinese Crisis Management. Asia-Pacific Review, 22(1), pp. 73-99. CrossRef link

Hall, T. (2019, September 4). Why The Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands Are Like A Toothpaste Tube. War on the Rocks. https://warontherocks.com/2019/09/why-the-senkaku-diaoyu-islands-are-like-a-toothpaste-tube/

Keyzer, Z. (2020, May 27). Chinese embassy in France tweets anti-US, anti-Israel imagery in error. The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/international/chinese-embassy-in-france-tweets-anti-us-anti-israel-imagery-in-error-629403

Maizland, L., & Fong, C. (2024, March 19). Hong Kong’s Freedoms: What China Promised and How It’s Cracking Down. Council of Foreign Affairs. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/hong-kong-freedoms-democracy-protests-china-crackdown.

Malumfashi, S. (2020, October 22) Nigeria’s SARS: A brief history of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/10/22/sars-a-brief-history-of-a-rogue-unit

McKiernan, J., & Faulkner, D. (2024, February 29). Protests descending into mob rule, Rishi Sunak warns police. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-68429902

Mitter, R. (2013). China’s War with Japan 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival. London: Penguin Books.

Moss, K. (2022) Security or Liberty?: Human Rights and Protest, In M. Gill (ed), The Handbook of Security (pp.751-776). Singapore: Springer. CrossRef link

Panlee, P. (2021). Visualising the right to protest: Graffiti and eviction under Thailand’s military regime. City, 25(3-4), pp. 497-509. CrossRef link https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2021.1943229

Pesarini, A., & Panico, C. (2021). From Colston to Montanelli: Public Memory and Counter-Monuments in the era of Black Lives Matter. From The European South, 9, pp. 99-113. https://hdl.handle.net/10316/96717

Silverstein, J. (2021, June 4). The global impact of George Floyd: How Black Lives Matter Protests Shaped Movements Around The World. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/george-floyd-black-lives-matter-impact/

Vuori, J.A. (2008). Illocutionary Logic and Strands of Securitization: Applying the Theory of Securitization to the Study of Non-Democratic Political Orders. European Journal of International Relations, 14(1), pp. 65-99. CrossRef link

Vuori, J.A. (2011). How To Do Security With Words: A Grammar of Securitization in the People’s Republic of China. Turun, Yliopiston Julkaisuja.

Wall, I.R. (2023). The Right to Protest, The International Journal of Human Rights, 28(8-9), pp. 1378-1393. CrossRef link

Wallace, J.L., & Weiss, J. C. (2015). The Political Geography of Nationalist Protest in China. The China Quarterly, 222, pp. 403-429. CrossRef link

Wee, S. & Duncan, M. (2012). Anti-Japan protests erupt in China over islands row. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/anti-japan-protests-erupt-in-china-over-islands-row-idUSBRE88E01I/

Wines, M. (2012, May 6). In Rise and Fall of China’s Bo Xilai, an Arc of Ruthlessness, The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/07/world/asia/in-rise-and-fall-of-chinas-bo-xilai-a-ruthless-arc.html

Young, K. (2021). Remembering George Floyd and the Movement He Sparked, One Year Later. National Museum of African American History and Culture. https://nmaahc.si.edu/about/news/remembering-george-floyd-and-movement-he-sparked-one-year-later