Summary

This paper employs Gaventa’s ‘powercube’ framework to examine how the Scottish community land movement has woven together different forms and sources of power in pursuit of local development. It finds that, while localism is a strong element in community land action, connections to institutions operating at wider spatial levels have been vital to the growth of the movement. It explores the Scottish Highlands and Islands context that has facilitated these connections. It also discusses the movement’s relationship with states and markets, noting both its emergence in the context of their perceived failures, but also analysing its engagement with them. It draws on primary research carried out by the author in Scotland, including ethnographic research into the working of two community land initiatives at local level, and into the community land movement more widely. It concludes with some remarks about community-led development, states and austerity; and contemporary developments in Scotland.

Introduction

Over the last 20 years, a series of distinctive local initiatives have emerged in the Scottish Highlands and Islands. Initially labelled ‘community buyouts’, thereby counterposing them to ‘management buyouts’ of company shareholdings, they saw locally-constituted organisations pursue development goals through buying control of the land around them. Today, community land initiatives (CLIs) – a term used to refer to any locality-based group that controls, or is considering control of, land in the name of the community – are found across Scotland. In some areas they have become major landowners. They vary in size, activities and other characteristics. However, most are structured as companies, with locally-elected directors, and engaged in multiple economic and social projects in their areas.

From the emphasis on ‘community’ and local control it will be seen that localism is a strong theme in this movement. Yet a considerable factor in its growth has been its success in joining up local action with action at regional and national levels. Local activists formed the core of a wider movement that connected local authorities, development agencies and political bodies to create technical, financial and legal powers for local organisations. This paper briefly tells this story, and considers what it means for the debates over states, markets and the third sector on which this special issue focusses on. It does so by drawing on data collected for the author’s PhD on Scottish community land ownership, including primary qualitative research: at local level with two CLIs, and with the wider community land movement.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section gives a little more detail on what Scottish CLIs are. It then sets out the methodological approach to power and local development, indicating how this drove the author’s research, and underpins the analysis. The wider connections that have facilitated local empowerment will then be explored, looking both at the immediate ‘visible’ links between institutions at various spatial scales, and at the wider cultural and historical context. The picture of the community land movement that has been built up will then be analysed in terms of its implications for contemporary debates about localism and austerity, and the role of states and markets in community development.

Scottish community land initiatives

The first of the contemporary Scottish CLIs was the Assynt Crofters’ Trust in the North West Highlands. In 1992 the landowner of much of Assynt was declared bankrupt and the area put up for sale for the second time in three years. Local crofters1 formed a company to buy the land they lived and worked on; land which had been in the hands of absentee private landowners for generations (MacPhail, 2002; MacAskill, 1999). Other local groups followed, especially in the Western Isles, where today the majority of the land is in community ownership, and the majority of the population live on community-owned land (MacKenzie, 2011). In 2010, the umbrella body Community Land Scotland (CLS) was formed, which today has 54 members (CLS, 2015) – groups who either own land, or plan to do so. But there are many more – the Scottish Community Woodlands Association, for example, has around 200 member organisations across Scotland (CWA, 2015), including some overlap with CLS. A recent survey by the Development Trust Association Scotland found 17 very large-scale community land owners, but a further 287 that owned substantial physical assets, that is to say, more than just the local community centre (Black and Leeman, 2012). And while the large-scale initiatives are concentrated in the West Highlands and Islands, the wider community assets groups can be found across Scotland.

The CLIs, that this article focusses on, are almost all legally structured as companies limited by guarantee. While on the surface these companies are conventional enough, being controlled by shareholders (“members of the company”) that elect the Board of Directors, in practice they are structured so as to act as local democratic organisations. Shares are limited to one per member, are non-tradeable and bring no financial return: they are effectively simply a right to vote on the affairs of the company. Further, membership of the company is generally restricted to residents of the local area, and typically the majority of the Board of Directors must also be local residents. Membership is not automatic: residents do have to make the decision to join the company; however this generally costs £1 or is free.

Their activities are generally very wide-ranging. Like Community Land Trusts elsewhere in the UK, many CLIs do get involved in housing – although generally in partnership with a local Housing Association. But they are much more than housing providers: they are also active in the areas of economic development, social service provision and environmental work. As one activist put it, they are effectively “very local development agencies”. The biggest CLI, Storas Uibhist, owns 90,000 acres, has a 7MW wind farm and is managing a £10m redevelopment of a harbour – as well as several tourism businesses, almost a thousand crofting tenancies, and is constructing storm defences along 20 miles of coastline (Community Land Scotland 2014). Many CLIs could display a similar breadth of activities, if not all on the same scale.

Power, place and change

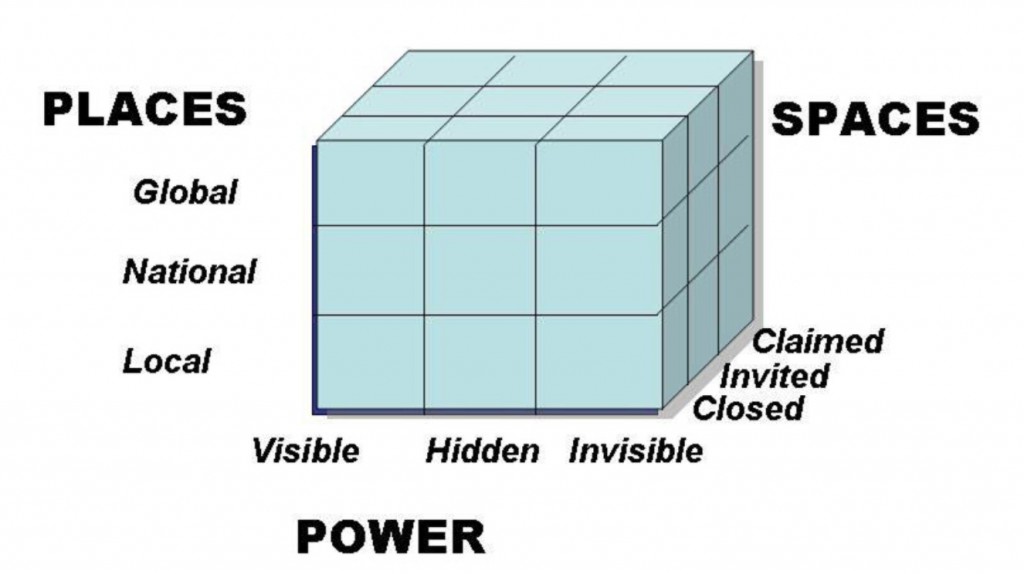

This paper takes power as the key concept for analysing how CLIs have made a difference to the social world. The literature on social power is wide-ranging and contains many competing schools of thought (Haugaard and Clegg, 2008; Scott, 2001); it is even argued that the concept is “essentially contested” (Lukes, 2005). However, as this section will set out, the ‘powercube’ model developed by Gaventa and colleagues fits well with the study of community land, and was chosen to guide the author’s doctoral research.

Firstly, as the diagram makes apparent, the powercube offers a way of integrating concerns with place, and spaces of engagement, with power. ‘Place’ is used to indicate different geographical scales of action. The suggested basic categorisation is threefold: local, national, global. Gaventa suggests that power is found at many different levels of place, and emphasises the importance of connections between levels – ‘vertical links’ – in social change.

Now, CLIs are almost all organised around communities of place – rather than other potential binding factors (e.g. gender, age, ethnicity, or occupation). The importance of local control of resources is prominent in the verbal and written statements produced by CLIs. Yet the issue of community land has attracted attention and action from institutions at many other levels (including the Scottish Government). Therefore, adopting an approach that examines the relationship between power at local level, and at other levels, seemed important for this study.

‘Space’ refers to social ‘spaces for engagement’ (Gaventa, 2006a: 27), any social context or practice where people come together. Focussing on the role of such spaces in power relations, in particular in relation to governance and decision-making, the cube uses a threefold categorisation of ‘closed’, ‘invited’ and ‘claimed/created’ spaces. A space is closed to an actor if they cannot participate directly in it: a space where:

elites (be they bureaucrats, experts or elected representatives) make decisions and provide services to ‘the people’, without the need for broader consultation or involvement. (Gaventa, 2006a: 26)

‘Invited’ spaces are those in which participation is possible, but on the terms of those who created the space. Many of the initiatives associated with the co-production of public services – service user groups and others – broadly have this character. ‘Claimed’ or ‘created’ spaces are those where actors have the power to define the terms of participation – whether by claiming control of a space that was previously less open, or through creating their own space, for example through self-organised social movements. Spaces can be categorised from a range of different actors’ perspectives. The parliamentary committee (or even London gentleman’s club) that is a closed space to most people, may be seen as claimed or created by the MPs who use it. The key insight is that it matters how and by whom a space was created, and what the ‘terms of engagement’ in it are (Gaventa 2006a: 26).

The formation of a CLI creates new spaces for decision-making on resources at local level. These have ‘terms of engagement’ which are different to other pre-existing spaces. The powercube offers a way in to understanding the implications of this. In particular, participation in CLI spaces is formally open to all residents; and it includes the decision-making power, through voting, over the management and activities of the organisation. These ‘terms of engagement’ are different to those governing local authority development planning processes, where final decision-making power rests with officials: these are perhaps ‘invited’ spaces. They are also different to private landowners’ decision-making structures: while some landowners consult with local residents about land use, such consultation tends to be at the invitation of the landowner, and on their terms. It does not amount to decision-making power over their actions: this is often ‘closed’ to most local residents.

Finally, explicitly addressing power, the powercube posits a threefold (again) typology of ‘visible’, ‘hidden’ and ‘invisible’ power, corresponding to Lukes’ three ‘dimensions’ or ‘faces’ of power (Lukes, 2005). ‘Visible’ power we can see in open action and struggle, formal power ‘on paper’ and out in the open. ‘Hidden’ power is behind-the-scenes, whereby regulations and procedures empower some and disempower others. Thirdly, there is the “invisible” power of ideas, habits and culture – affecting patterns of thought and behaviour in ways we may often hardly be aware of.

These tools drove the research. For example, at local level, a range of local perspectives on participation in CLIs, and of local understandings of ‘community’, were explored to see if ‘visible’ power to participate was affected by more ‘hidden’ or ‘invisible’ factors. Beyond the locality, power relations between groups at different geographical levels were considered. Key issues included how external organisations – through funding criteria or their decisions over which local bodies to engage with – might have some power over what kinds of spaces local organisations create.

This study also expanded on the powercube approach to power. Lukes’ original typology of power focussed primarily on conflict in social relationships (whether or not the conflict was ‘visible’). Here, if one actor gains power, the other loses it: this is a ‘zero-sum’ concept of power. The total sum of power is not changed, only its distribution is altered. However, power can also be seen as the capacity for action, and found in a much wider range of relationships. An actor’s power is simply what they are able to do. This is an ‘additive’ concept of power: it is possible for the total sum of power to be increased. This might be by one actor teaching themselves a new skill, but it might also be by two or more actors working together to achieve a goal that they could not achieve on their own: ‘positive sum’ or ‘collective’ power (Mann, 1986), or ‘power with’ (Chambers, 2006). This working together might be on a strictly equal footing, or it might be hierarchical to some degree – and indeed, different sorts of power relationship may well be ‘intertwined’ in ‘most social relations’ (Mann, 1986: 6).

It is therefore important to look for whether CLIs have created power, not just for conflicts over its distribution. This might be through enabling intra-community cooperation in ways that had not previously happened; or through accessing new resources. The identification of power with control over resources is perhaps too simplistic –’visible’ control may be influenced by other factors, as suggested above (Lukes, 2005, Kabeer, 1999: 14-17). Nevertheless, when it comes to the power impact of local participation in CLI decision-making, it clearly matters what the CLI owns, and what it is trying to do with it. While power struggles over the village green are one thing (keenly felt though they may be), those over a multi-million pound local development project covering a whole locality are quite another. So, the study of how CLI local development projects were formed, how they were progressing, and what they had achieved, became part of the research – as did the study of the impact of CLIs’ terms of access to resources beyond the locality.

Methodology and research process

The data on CLIs used in this paper was largely collected between 2011 and 2013, for the author’s PhD on Scottish community land ownership. Data collection had two main focii: on community land action at local level, and at connections between the local level and other levels of action. Both elements of the study required the collection and analysis of secondary data: official statistics, reports, material produced by community land advocates and opponents, etc. However, as previously outlined, the research was driven by a conception of power that emphasises getting underneath the ‘visible’ surface evidence of its distribution. Therefore, the approach was primarily qualitative, and included considerable time devoted to primary ‘field’ research.

For the local level element, this involved spending around three months over one year on the Sleat peninsula of the Isle of Skye, studying the two CLIs active there. These are the Sleat Community Trust (SCT), whose remit covers the entire peninsula; and the Camuscross and Duisdale Initiative (CDI), which is concerned with the two neighbouring settlements of its title. In addition to participating widely in local life, the author attended public and private meetings in relation to CLI activities, and interviewed a total of 69 people – just under ten per cent of the adult population (Census, 2011). These were as wide a range of people as possible across various social and demographic characteristics, including – in addition to age, gender, length of residence in the area, etc. – type and extent of participation in community organisations.

For the wider element of the study, nine key individuals active in community land and empowerment beyond Sleat, across the public and third sectors, were interviewed. In addition, two CLS annual conferences and one regional workshop were attended. Clearly, some research time was spent with what was unambiguously the ‘movement’ – CLS and associated activists. However, the wider perspective of what might be termed the community land ‘sector’ – those involved professionally with community land issues, but not campaigning on them nor necessarily exclusively dealing with them – was also sought out. Finally, the PhD and this paper also draw on research conducted with others for a Scottish Parliament study of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 in operation (Macleod et al., 2010), which involved surveys of and interviews with CLIs across Scotland.

Going beyond the local: joined-up action across different spatial-institutional levels

The powercube approach is helpful in understanding community land initiatives in context. Now, it is true that their work at local level is a very significant part of how they build power and make change. By owning an asset – particularly one as multifunctional as land – they put themselves in a position to initiate a wide range of projects, rather than merely react to others’ projects through the planning process. And they are structured to allow local control and give local residents access to decision-making about the use of their local resources – something which helps to engage people and get them to contribute skills, time and energy. More deeply, these initiatives challenge received wisdom – or should that be received pessimism – about what communities can do and what places can be like. All of this is at the heart of what they do.

However, CLIs have also worked carefully beyond their localities to empower themselves, and have in turn benefited from external support designed to nurture the growing movement. In the Highlands and Islands, the regional development agency, Highlands and Islands Enterprise, has been important in providing dedicated advice, support and funding to CLIs through their Community Land Unit (now the Community Assets Team). Support from the region’s local authorities,2 particularly Highland, has also been important.

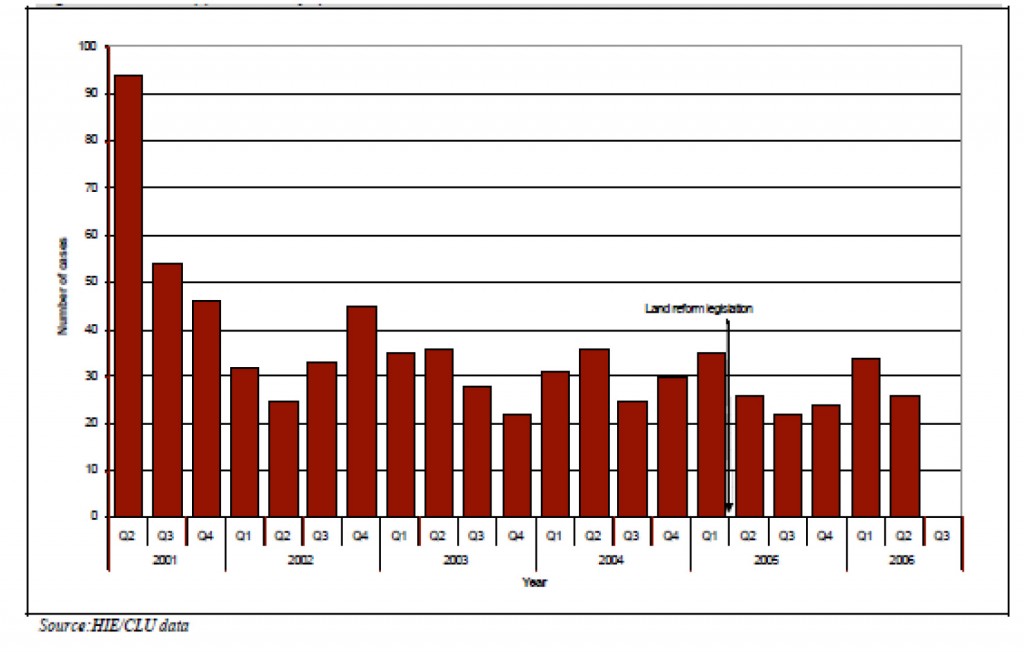

At Scotland level, funding from Lottery programmes for Scotland – particularly the Scottish Land Fund – has been crucial to grow the movement. The first Scottish Land Fund ran from 2001 to 2006. It was specifically designed to aid community acquisition of land, and made grants of over £1m to several high-profile CLIs, as well as many smaller grants to lesser-known bodies (SQW, 2007). After 2006, there was no such dedicated funding for land purchase until 2012 when, following campaigning from land reform activists, the Scottish Government opened a second Scottish Land Fund (administered by the Lottery and HIE) which still operates today.

The Land Reform (Scotland) Act of 2003 (hereafter the ‘Land Reform Act’) has also been important. This gives rural community groups a right of first refusal if land in their area comes up for sale: although this right is conditional on having pre-registered an interest in that land. Ministerial acceptance of a registration of interest is not guaranteed, and is set about with conditions about group constitution, objectives, etc. This registration procedure is quite lengthy and bureaucratic, and very public: it can have a significant impact on community-landowner relations (Macleod et al., 2010: 83-87). Only a minority of community landowners have acquired land through it (Macleod et al., 2010: 19). However, its very existence, and the high profile political process of developing and passing it, has been part of a cultural shift around land ownership that has empowered community initiatives. As one activist put it, when parliament is debating land reform, it creates “a good bargaining environment” (Macleod et al., 2010: 74).

This is not only a story about Scottish institutions. At UK level, renewable energy policy has been important in transforming windswept areas of moorland from burdens on the landowner to sites for potentially lucrative wind farms. However, the emergence of these initiatives in the Highlands and Islands, and the relatively swift and supportive response of regional and Scottish state institutions, is particularly notable. Why did (and do) all these people act to support local community control of land?

Going beyond the foreground: the enabling context

To answer this, it is helpful to return to the “hidden” and “invisible” forms of power discussed earlier. Firstly, there is the historical context of the ‘land question’ in the Highlands. Since the Victorian era, a ‘Balmoralised’ view of the Highlands has held sway, in which the region – symbolised by mountains, whisky, tartan and bagpipes – is seen as the authentic Celtic soul of Scotland (McCrone, 2001: 39-41). Yet ironically, around the same time as this romantic view was taking hold outside the region, within it there was rapid modernisation and social turmoil. The shift from clan feudalism to capitalism saw massive population displacement, often forced to some degree, occasionally violent: the Highland Clearances.

These processes have had cultural and structural consequences. Across Scotland, widespread concern arose in the late 19th and 20th centuries over the ‘Highland problem’ of decline and underdevelopment (Munro and Hart 2000: 10; MacKinnon, 2002: 311; Darling, 1955). Within the region, the cultural legacies of this history include a sense that land ownership is a political issue: it is far from ‘invisible’ or taken-for-granted. There is also a distrust of landowner, and non-local, control of local affairs and resources.

In terms of structural legacies, there are still many large parcels of land – sometimes whole localities – owned by single owners (Wightman, 2010: 106-8, 115-120), and prices for these are low relative to similar acreages elsewhere in the UK. A cultural preference for personal recreational land use, rather than development, among landowners (MacGregor, 1988; MacMillan et al., 2010; Wagstaff et al., 2013) is linked by some to economic and demographic decline (MacGregor, 1998: 403-4; Wightman, 2010: 168). Certainly, demographic decline is a key structural feature of the recent history of the Highlands and Islands. Until recently, populations had been falling across the whole region for over a century; this decline continues in several areas (OECD, 2008: 13; MacKinnon, 2002: 311; Darling, 1955).

Politically, concern across Scotland with the ‘Highland Problem’ led to the creation of specific regional institutions and structures to address it: notably Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE), created in 1965 as the Highlands and Islands Development Board (HIDB). Uniquely for a regional development agency, it has a remit for social as well as economic development. Further, from the start it devoted attention to landownership as a key development issue (Lloyd and Shucksmith, 1985: 119-120), and HIDB was given powers of compulsory purchase of private land, where deemed necessary to progress projects. At a more local level of action, there is also the crofting system. Following post-Clearances reforms, this gives individual crofters very secure tenancies, and creates village-level collective structures (Grazings Committees) with further powers for managing land.

These various legacies of history have led to the development of a broad consensus over goals and approaches to Highland development, existing between a wide range of people – across public, private and third sectors, from ‘ordinary’ Highland residents to its officials and politicians, and across wider Scotland. This includes policy goals of growing the population, as well as the economy; of making modern services and living standards accessible, but also preserving cultural traditions; and a sense that, to date, the operation of markets – in land and other sectors – have tended to hinder, rather than further, these goals. Of course, this consensus is by no means universal, and there are many debates within it. But, there is widespread popular demand for regeneration: ‘lights going back on in the glen’. There are policymakers and officials tasked with achieving such goals, and there is support from public and politicians across Scotland. Thus, as McCrone notes (2001: 40):

the first Scottish government elected in May 1999 let it be known that land reform was to be one of its key priorities, something which in England would cause considerable puzzlement.

It is notable that CLIs themselves often point to demographic indicators before all others, as evidence of their impact (e.g. Bryan and Westbrook, 2014: 1-2; McMorran and Scott, 2013: 146; Campbell, 2008: 32). This may include a focus on school rolls, and numbers of resident children, as indicators of “demographic sustainability” (Bryan and Westbrook, 2014: 2).

In this context, the emergence of efforts to intervene in land markets for developmental reasons is perhaps not surprising. However, what still needs explaining is: why was it community groups that intervened? Why not the state?

The emergence of community land initiatives

In fact, the state did attempt to intervene. HIDB was set up with powers of compulsory purchase of land, and in the 1970s, it attempted to use them. However, these ‘visible’ powers for state intervention in land markets were undermined by ‘hidden’ power: from the UK Treasury, that controlled the funding necessary for such interventions; and from government legal advisors, who deemed compulsory purchase to be unworkable in practice. Senior HIDB staff requested that the UK government amend and expand its powers to deal with these problems. But as the UK government became increasingly neo-liberal in outlook, especially following the Conservative election victory in 1979, this request was refused (Lloyd and Shucksmith, 1985: 122-125; MacGregor, 1988: 403-4).

With HIDB’s hands tied, any challenge to existing patterns of landownership would have to come from elsewhere. By the late 1980s, some other state bodies were making moves towards this. Michael Forsyth, Secretary of State for Scotland, attempted to sell state-owned crofting lands to crofting groups. Although his offer was seen by some as simply privatisation, and greeted with suspicion by many, the idea of local collective ownership had been given a high profile airing. And at the same time, several members of the Highland Council were advocating local authority intervention in some cases of community dissatisfaction with landowners.

However, when the breakthrough came, it was from ‘below’; the Assynt Crofters Trust, created by members of a local branch of the Crofters’ Union. While they received little financial help from the public sector, there was encouragement and practical assistance in various ways. As those interested in land reform in local authorities and HIE (as it now was) came to realise, the idea of ‘community land’ offered a new way of addressing issues around land and development, that might sidestep both the ‘hidden’ blockages that previous state-led efforts had encountered, and also the democratic deficit of conventional private ownership. Indeed, the Assynt Crofters – who mixed development goals with a strong sense of the injustices of private land ownership – even came to be championed as a Highland success story by the Thatcherite Forsyth.

Action in and by the state remained significant, however. The election of a Labour government at UK level in 1997 changed power relations around land in multiple ways. The new government’s Scottish Office Minister, Brian Wilson, was associated with HIE’s establishment of the Community Land Unit in the same year. Most obviously, the Labour victory led to devolution and new institutions at Scotland level. The Scottish parliament was a new decision-making space, where that hidden, agenda-setting power was not already captured. Not only does England lack a comparable cultural context, the ‘hidden’ power structures are different too. Firstly, the Scottish parliament inevitably has greater interest in Scottish issues than the UK parliament – and more time to consider them. Secondly, the Scottish parliament has no House of Lords. Many Lords are large landowners (Glass et al., 2013: 23; MacKenzie, 2012: 37). It is, perhaps, unlikely that the Land Reform Act that was passed in Edinburgh would have survived at Westminster.

Thus far, this article has outlined the origins and structure of the community land movement in Scotland, showing how the emergence and growth of a locality-based movement was influenced by multifaceted power relationships over much wider spatial and temporal scales. The next two sections will analyse CLI engagement in markets, and with state bodies, in more detail.

Communities and markets: funding and power relations

Historically, land markets were a ‘closed’ space for Highland communities. They were deeply affected by transactions in those markets, but unable to participate in them. The community land movement has changed that.

Crucial to this change has been external funding. The availability of dedicated funds for land purchase from the first Scottish Land Fund had a significant impact on the growth of the community land movement. While early CLIs funded most of their land acquisitions from the general public, this was time-consuming and not necessarily reliable. Commercial finance was also not a viable option. While Highland land is relatively cheap compared to much of rural England, still Highland estates cover large areas and often sell for millions of pounds. However, these prices reflect their value as a status symbol, and perhaps as a long-term investment, more than their operational profitability. Potential revenues from renewable energy may be changing the economic prospects of tracts of windswept moorland, but it is still likely to be very hard for a community group to get a business mortgage to buy a Highland estate.

The generosity of the funding available is significant also. The first Scottish Land Fund sometimes made awards running into the millions of pounds, allowing CLIs to take outright ownership of their localities. The second Fund, currently in operation, has an upper limit of £750,000 for grants. Therefore, to buy a significant acreage of land, CLIs may have to go into partnership. For example, one group has bought a forest part-funded by the Land Fund, but most of the money has come from a commercial timber company; as the company have put up most of the money, they have the commercial forestry rights (Big Lottery Fund, 2013; Colintraive and Glendaruel Trust, 2013). In this case – where the bulk of the land, and any income from it, will be the property of the timber company rather than the community group – community ownership is not quite as empowering as it might have been had the community been able to buy all the land and take full control.

Funding beyond the purchase is also important. Several CLIs are now running at an operating profit, meeting their core staff and other costs from estates that had been loss-making for decades (Hunter, 2012: 110, 162). Still, early years development funding is crucial. It is well-established in land reform literature internationally that simply transferring assets, without attention to post-transfer development, including seed funding, generally leads to new proprietors struggling and having to sell the assets for short-term survival (Deininger, 1999: 5; Chimhowu 2006: 40). This has not happened in Scotland. One reason is that HIE support includes an “aftercare” package, which generally includes funding for a development officer for 3 years. Having a full-time officer to run projects and develop income streams is invaluable to CLIs in the early post-purchase years. Many CLIs will have all but exhausted their resources in their campaigns to acquire land; further, as noted above, the estates they acquire are often not generating much, if any, income at the time of purchase. External funding of such a development officer is intended to help CLIs survive this difficult ‘start-up’ period, and develop income generating activities, with the hope that they should be covering their core costs from these activities by the end of it.

Such an officer typically does the day-to-day work to deliver the land use projects the CLI wishes to undertake; helps run the organisation’s governance and administration; and also works to establish income streams for the organisation. These tasks are evidently key to the future survival and success of the CLI, but are also inevitably difficult for CLIs to fund out of their own resources in the early post-purchase period – it takes times to get projects and income streams running.

The following chart illustrates further the relative impact of funding and legislation. It shows applications to the first Scottish Land Fund, from its launch in 2001 to its close in 2006. The initial spike of applications indicates how eagerly anticipated it was. It is clear that the coming in to force of the Land Reform Act in 2005 did not provoke any rush in applications to the Fund, even though it was still the primary source of land acquisition finance at that time. It was the funding, rather than the (admittedly cumbersome) legal mechanisms of the Act, that community groups saw as the more powerful tool for them.

So some – even many – CLIs undoubtedly were empowered by their relationship with funding bodies. Yet there is more to the picture than this: the relationship between the funded and the funders is complex. In one view, they are mutually dependent. Certainly, without credible projects and applicants, funding bodies do indeed lose their raison d’être. As a speaker at a CLI public meeting put it:

Funders are our friends! They need us as much as we need them! (CDI Sustainable Community Hub community consultation meeting, May 2012)

Here is a view of the funder-CLI relationship not as zero-sum – with power being transferred from one party to the other; but as collaborative – with both parties benefiting. Money gives CLIs the power to own land and embark on projects; disbursing money for successful projects helps hit funding agencies’ targets and in turn gives them, or groups of staff within them, power in their negotiations with their funders.

In some cases, the power relationship is not so collaborative. Many in the third sector will be familiar with conflicts arising over the details of projects to be funded, and relatedly, the burden on volunteers of complying with accounting and reporting requirements and timescales. The ability to write good application forms and navigate the bureaucratic world of funding agencies is itself a key competence for community activists, and skilled practitioners are recognised and appreciated by their colleagues and community members.

Perhaps more unusually, the community land movement has sometimes seen tensions over definitions of community between CLIs and external agencies. Most funders define the community as all residents in a given area. Yet this definition does not fit the very first CLI: membership of the Assynt Crofters’ Trust is open only to crofters (this has been a source of some tension between the Trust and some public bodies). For one of Sleat’s CLIs, it was Government officials administering the Land Reform Act that disagreed with the local Camuscross Community Initiative as to where the physical boundaries of the community lay. Scottish Government officials thought it included the adjacent settlement of Duisdale; however, the fledgling Camuscross group felt the two communities were distinct, and that they were not yet ready to expand. The officials insisted that use of the Land Reform Act depended on adopting their definition; Duisdale residents voted in favour of joining with Camuscross; and the enlarged Camuscross and Duisdale Initiative went on to successfully use the Act.3 While the new group generally works well, it shows the power that government holds in such cases; and it is to the relationship between community and state bodies that we now turn.

Communities and states: a coalition for development?

In addition to money, CLIs have also built power through engaging with the institutional structures referred to earlier – notably Highlands and Islands Enterprise’s Community Land Unit. These were created specifically to give advice, technical expertise, and indeed moral support, to the community land movement.

This has been another key relationship for many CLIs. Many communities contain a remarkable range of skills and knowledge, from practical land management to community organising to media, financial and legal expertise: but inevitably this is uneven. Support from beyond the local level is required to even out the distribution of such powers. Although self-organised peer networks like Community Land Scotland, Community Energy Scotland and the Community Woods Association have played a role, state agencies have been very important. This contribution is recognised by many, as this quotation from an experienced activist indicates:

To make community landownership work (…) You do need adequate funding. You do need legislation because that demonstrates the political will behind it. And you do need the technical support where it’s missing (…) Personally again I think it’s regrettable that Scottish Enterprise4 do not have a social function, because certainly talking with people in Dumfries and Galloway (…) they can’t do community development the same way we can in the Highlands and Islands, and that’s why it’s happened in the Highlands and Islands, I’m positive. (‘Graham’, community land movement activist, interview with the author: October 2012)

The existence of a broad consensus around certain approaches to Highland development was discussed earlier. What the community land movement has done is build on this to create an informal ‘coalition for Highland development’ around local land ownership. It is notable that this has been fostered not only by shared policy objectives, but also by long-term personal relationships. While the public, private, and the community or third sector may appear separate, in fact some of the people involved have crossed from one to the other. Indeed, many of the leading individuals have been working on these issues, with each other, for over 20 years.

Outside of HIE, members of this coalition can certainly be found elsewhere in the state. At local authority level, there has been a strong tradition of support for CLIs from the principal Councils in the Highlands and Islands. Yet there are tensions also. In this region, the local authorities are not always felt to be very local. Highland Council in particular covers an enormous area – 200 miles from North to South. It is therefore possible that CLIs can be seen as usurping the Councils’ claim to be a ‘local authority’. This status gives CLIs some local legitimacy – enhancing their ‘invisible’ power. At the same time, activists are wary of allowing an expectation to develop that they can simply step into the local authority’s shoes with regard to, for example, the outsourcing of difficult and costly to deliver services in remote areas.

The statutory governance bodies that do exist at local level in Scotland are community councils: but as effectively feedback mechanisms for the local authority, they are clearly a rather limited ‘invited’ space. Some active community councils, including that in Sleat, play a useful role as a space for interaction with a wider range of external bodies, public and private. But they have small budgets and, unlike many European municipalities, they are legally unable to own assets and undertake economic development. This leaves them with little power to initiate any projects of their own. CLIs’ greater powers, including to raise funds, makes them the more attractive vehicle for promoting local development.

Conclusions: new public ownership?

Both markets and the state have been important in the development of the community land movement. The importance of finance for land acquisition arises because Scottish land reform has been ‘market-based’ (Borras, 2003; Deininger, 1999). Land has been transferred for between ‘willing sellers’ and ‘willing buyers’, not through legal confiscation – or popular occupation as in Brazil (Wolford, 2010). In a neo-liberal era, when market solutions enjoy considerable ‘invisible’ power, particularly among policymakers, this has made land reform politically possible. However, it has left it to existing landowners to dictate its pace, through their power to decide whether or not their land enters the market; and it exposes CLIs to market risks. As companies they often take constitutional steps to limit any personal liabilities for community members, and ‘lock’ their assets; but in principle, they could go bankrupt.

Consideration of such issues has led to the community land experience playing a part in inspiring a broader movement in Scotland that is re-imagining the role and nature of the state. From moves to reinvigorate very local democracy (Bort et al., 2012; Commission for Strengthening Local Democracy, 2014; Birnam Land Reform Workshop, 2015), to scholars arguing (Cumbers, 2012: 219) for:

a reconstituted public ownership, framed around economic democracy and public participation in decision-making […which will] involve a rethink of the relations between geographical scales there is a search for new connections between localities and other levels of power that is less bound to market-based solutions.

The role of the state has also clearly been important, not least in assisting community groups with their participation in markets. Both public funding, advice and legislation have altered CLIs’ ‘terms of engagement’ in these spaces. Yet it should not be taken to suggest that CLIs are either the products of either statist intervention (Scottish Daily Mail, 2003), or anti-state neoliberal efforts at government through community (Levitas, 2000; Rose, 1999). Indeed CLIs were not created, or contracted, as vehicles of public policy. Instead, they emerged following the failure of various public policy approaches to the ‘land question’, and pragmatically engaged with states and markets in various forms in pursuit of their goals. Emerging in a neo-liberal era, they took the legal form of companies. However, they also drew on local cultural understandings of the significance of land, and of collective and communal endeavour: a reconfiguration of the ‘public’ to local level, in relation to land ownership. The history of local disempowerment, with decisions over resources made in closed spaces or faraway places, was seen as a key cause of local individuals’ constrained choices and long-term community decline: local decision-making emphasised as the key to building a better future.

Yet from the outset, this movement – while emerging at a very local level, and with a strong attachment to place at its heart – was building extra-local relationships. As the powercube analysis helps make clear, their operation enmeshes them in much wider networks of power relations; what they can do locally is significantly affected by their engagement in these. It is clear that ‘vertical links’, between local and other levels, have been important in their success.

This suggests a key lesson for policymakers who would promote local initiatives in an age of public sector austerity. Simply put, in the short term at least, stimulating or supporting localism demands resources: money, and institutions and people. Increasing local power is not the same as decreasing central power. In fact, successful localist development is not based on a zero-sum relationship, where if one party relinquishes power (and responsibility) the other is automatically empowered. Rather, the promotion of localism should be seen as a collaborative relationship between local and other actors, where power is not only redistributed but also created. This will require the commitment of resources from all parties.

On this note, this paper will conclude with two recent developments in Scotland. Firstly, an interesting process is underway in the Western Isles. The majority of the population here live on land in community ownership; likewise, the majority of the land area is in the hands of CLIs. Comhairle nan Eilean Siar (the local authority) and the combined Western Isles CLIs have begun a series of meetings to develop ‘a shared agenda’ and better ways of ‘joint working’, particularly on ‘the economic development priorities we share’, while acknowledging that they have ‘different responsibilities’ (Community Land Scotland, 2014: 1).

Secondly, the Scottish Government is currently consulting on new land reform legislation which could change property rights across urban as well as rural Scotland; and a Community Empowerment Act has just been passed by the Scottish Parliament, extending the powers in the existing Land Reform Act. Whereas for some years the ‘invisible’ power of the Highlands in Scottish culture also perhaps provided a means of keeping land reform as a regional ‘special case’, it seems that it is now breaking out of the supposedly ‘peripheral’ northwest, and spreading across Scotland. The relationship between power, space and place is being recast again.

1 Crofters are tenants of crofts; a type of agricultural smallholding with complex legal protections that are unique to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland.

2 The Highlands and Islands region contains six local authorities: Highland (the most extensive), Argyll and Bute, Moray, Orkney Islands, Shetland Islands, and Eilean Siar (the Western Isles).

3 They used the Act to purchase a local reservoir that Scottish Water was disposing of. Scottish Water had agreed to halt their auction of the reservoir, on condition that the community group used the Land Reform Act approval and valuation procedures to establish that their purchase was in the public interest and at a fair price.

4 Scottish Enterprise is a Regional Development Agency, similar to those that until recently operated in the regions of England and Wales. Its remit is to promote economic growth; in contrast, Highlands and Islands Enterprise is charged with promoting economic and social development.

Tim Braunholtz-Speight. Email: timbrs@fastmail.fm

Big Lottery Scotland (2013a) Scottish Land Fund – First Awards [Online] [Accessed 14 June 2013]. Available from: www.bigblogscotland.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/22/slf-national-22-02-13.pdf

Birnam Land Reform Workshop (2015) Submission to the Scottish Government consultation on Land Reform. Available from: http://radicalindependence.org/2015/02/23/the-land-belongs-to-everyone-and-to-no-one-a-radical-response-to-the-scottish-governments-land-reform-consultation/

Black, T. and Leeman, L. (2012) Community Ownership in Scotland: a baseline study. Edinburgh: Development Trusts Association Scotland – Community Ownership Support Service.

Borras, S. (2003) Questioning Market-Led Agrarian Reform: Experiences from Brazil, Colombia and South Africa. Journal of Agrarian Change, 3, 3, 367-394. CrossRef link

Bort, E., McAlpine, R. and Morgan, G. (2012) The silent crisis: failure and revival in local democracy in Scotland. Glasgow: Jimmy Reid Foundation.

Bryan, A. and Westbrook, S. (2014) Community Land Scotland: summary of economic indicator data. Tarbert, Isle of Harris: Community Land Scotland.

Campbell, L. (2008) Independent Review of the Knoydart Foundation. Report prepared for HIE, Kiltarlity: Campbell Consulting Ltd.

Chambers, R. (2006) Transforming power: from zero-sum to win-win? IDS Bulletin, 37, 6, 99-110. Brighton: Institute for Development Studies. CrossRef link

Chimhowu, A. (2006) Tinkering on the fringes? Redistributive land reforms and chronic poverty in South Africa, CPRC Working Paper 58. Manchester: Chronic Poverty Research Centre.

Colintraive and Glendaruel Development Trust (2013) Afforestations of delight [Online]. [Accessed 14 June 2013]. Available from: http://cgdt.org/2013/02/afforestations-of-delight/

Commission for Strengthening Local Democracy (2014) Effective democracy: reconnecting with communities.

Community Land Scotland (2014) Autumn Newsletter. Tarbert, Isle of Harris: Community Land Scotland.

Community Land Scotland (2015) Community Land Scotland [Online]. Available from: www.communitylandscotland.org.uk/members

CWA (2015) Community Woodlands Association [Online]. Available from: http://www.communitywoods.org/projects.php

Cumbers, A. (2012) Reclaiming public ownership: making space for economic democracy. London: Zed books.

Darling, F. F. (ed.) (1955) West Highland Survey. London: Oxford University Press.

Deininger, K. (1999) Making Negotiated Land Reform Work: Initial Experience from Brazil, Colombia, and South Africa. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2040, Washington DC: World Bank.

Gaventa, J. (2005) Reflections on the Uses of the ‘Power Cube’ Approach for Analyzing the Spaces, Places and Dynamics of Civil Society Participation and Engagement. CFP evaluation series 2003-2006: no 4. Paper prepared for the Dutch CFA evaluation, ‘Assessing Civil Society Participation’, coordinated by Learning by Design, and supported by Cordaid, Hivos, Novib and Plan Netherlands.

Gaventa, J. (2006) Finding the spaces for change: a power analysis. IDS Bulletin, 37, 6, 23-33. Brighton: Institute for Development Studies. CrossRef link

Haugaard, M., and Clegg, S. (eds) (2008) The Sage Handbook of Social Sciences. London: Sage.

Hunter, J. (2012) From the low tide of the sea to the high mountain tops. Stornoway: Islands Book Trust.

Kabeer, N. (1999) The conditions and consequences of choice: reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. UNRISD Discussion Paper 108, Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

Levitas, R. (2000) Community, utopia and New Labour. Local Economy, 15, 3, 188-197. CrossRef link

Lukes, S. (2005) Power: a radical view, 2nd edition. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

MacAskill, J. (1999) We have won the land: the story of the purchase of the North Lochinver Estate by the Assynt Crofters’ Trust. Stornoway: Acair.

McCrone, D. (2001) Scotland: the sociology of a stateless nation, 2nd edition. London: Routledge.

MacGregor, B. D. (1988) Owner motivation and land use on landed estates in the North-West Highlands of Scotland. Journal of Rural Studies, 4, 4, 389-404. CrossRef link

McKee, A., Warren, C., Glass, J. and Wagstaff, P. (2013) The Scottish private estate, pp63-85 in Glass, J., Price, M., Warren, C. and Scott, A. (eds) (2013) Lairds, Land and Sustainability: Scottish perspectives on upland management. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

MacKinnon, D. (2002) Rural governance and local involvement: assessing state-community relations in the Scottish Highlands. Journal of Rural Studies, 18, 307-324. CrossRef link

Macleod, C., Braunholtz-Speight, T., MacPhail, I., Flynn, D, Allen, S. and Macleod, D. (2010) Post-legislative Scrutiny of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, Report for the Scottish Parliament. Perth: UHI Centre for Mountain Studies.

MacMillan, D., Leitch, K., Wightman, A. and Higgins, P. (2010) The Management and Role of Highland Sporting Estates in the Early Twenty-First Century: The Owner’s View of a Unique but Contested Form of Land Use. Scottish Geographical Journal, 126, 1, 26-40. CrossRef link

McMorran, R. and Scott, A. (2013) Community landownership: rediscovering the road to sustainability, In: Glass, J., Price, M., Warren, C., and Scott, A. (eds) (2013) Lairds, Land and Sustainability: Scottish perspectives on upland management. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press: 139-172.

MacPhail, I. (2002) Land, crofting and the Assynt Crofters Trust: a post-colonial geography? (unpublished PhD thesis) Lampeter: University of Wales.

Mann, M. (1986) The Sources of Social Power: Volume One, a history of power from the beginning to AD 1760. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. CrossRef link

OECD (2008) Rural Policy Review: Scotland, UK. Paris: OECD.

Rose, N. (1999) Powers of freedom: reframing political thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. CrossRef link

Satsangi, M. (2007) Land tenure change and rural housing in Scotland. Scottish Geographical Journal, 123, 1, 33–47. CrossRef link

SQW (2007) Scottish Land Fund Evaluation: Final Report. Edinburgh: SQW Ltd.

Wagstaff, P. (2013) What motivates private landowners? In: Glass, J., Price, M., Warren, C., and Scott, A. (eds) (2013) Lairds, Land and Sustainability: Scottish perspectives on upland management. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press: 86-107.

Weber, M. (1978) Economy and Society. New York: University of California Press.

Wightman, A. (2010) The poor had no lawyers: who owns Scotland and how they got it. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Wolford, W. (2010) The land is ours now: social mobilisation and the meanings of land in Brazil. London: Duke University Press. CrossRef link