Abstract

The early to mid-2000s was a period of intense debate within the geographical literature about, in a variety of terms, the ‘relevance’ of the discipline to the policy world ‘out there’ beyond the academy. This article steps back for the first time from that debate in order to reflect critically on, synthesise and reframe analytically key arguments and insights that – despite their potential continued value for the discipline – became lost amidst the frenzied noise of its emotive and crossing conversations. The aim in doing so is to provide an innovative inclusive analytical framework within which to better understand and stimulate productive debate around the diversity of what ‘policy geography’ is and can be right across the discipline without compromising – indeed whilst strengthening – the intellectual quality and integrity of our geographical scholarship.

Introduction

The early to mid-2000s was a period of intense debate within the geographical literature about, in a variety of terms, the ‘relevance’ of the discipline to the policy world ‘out there’ beyond academia. A repeat of the discipline’s similar existential debate in the 1970s (Coppock, 1974), the language used differed widely – “useful knowledge” (Pacione, 1999), “relevance” (Staeheli and Mitchell, 2005), “scholar-activist” (Burgess, 2005), “border geography” (Castree, 2002), “grey geography (Peck, 1999) or “public geographies” (Ward, 2006). Yet despite the differing terminology the debate reflected a shared concern by many scholars of a “growing dealignment” (Peck, 1999: 132) from, and “missing agenda” (Ward, 2005: 311) of, spatially relevant policy engagement and influence. This was seen as a waste of the discipline’s undoubted critical and empirical insights and potential contributions to policy and society as well as a neglect of the significant spatial impacts of policy (whether aspatial or explicitly spatial in their focus)(Martin, 2001; Massey, 2001; Peck, 1999). It was seen too as a problem for the discipline itself through concerns that academic geography was becoming less highly regarded (both inside and outside the academy) and less critically incisive (Dorling and Shaw, 2002; Peck, 1999; Philo and Miller, 2014) via its claimed detachment and insularity.

It was by no means one-way traffic. Not all agreed that the discipline’s engagement with policy was limited or that even if this were true that it should be considered problematic. Indeed, perhaps the best way to summarize the policy geographies debate of the 2000s is disagreement – of positions, interpretations, values and priorities for the future. What is most striking perhaps reflecting back on that debate today is how fleeting, emotive and divisive its burst of intellectual energy was and how frequently lines of enquiry talked across rather than to each other. At the end of it all very little progress was made. As Ward summarised towards the end of the period, “[M]uch fist-shaking and head-nodding has taken place…[A]nd then…silence.” (Ward, 2007: 697).

And so to the present article, a forward-looking revisiting of the policy geographies debate of the 2000s to synthesise and pull through untapped but still relevant value from that literature. The timing is right to reflect back on these debates given the continued, indeed increasingly prominent, role of ‘out there’ academic activities since that time, whether for new research income, profile (individual or institutional), ‘relevance’ or ‘impact’. Within the debate fifteen years ago Castree introduced one of his many contributions by claiming that it was “something of a review, something of a critique, and something of a manifesto” (Castree, 1999: 91). This article takes similar starting points, though with less of a manifesto and instead a desire to step-back for the first time from that debate in order to reflect critically on, synthesise and reframe analytically key arguments and learnings that – despite their potential continued value for the discipline – became lost amidst the crossing conversations of colleagues largely “whining at each other” (Mitchell, 2006: 205). The aim in doing so is to provide an innovative inclusive analytical framework with which to better understand and stimulate more productive debate within the discipline around the diversity of what ‘policy geography’ is and can be. The hope is to enable colleagues right across the disciplinary spectrum to consider the potential value of their geographical insights to policy and the range of equally valid potential means of realising that value without compromising – indeed whilst strengthening – the intellectual quality and integrity of our scholarship.

The policy geographies debate of the 2000s: many storms in many teacups

The policy geographies debate of the 2000s was characterised by fragmentation, disagreement, vested interests and no little emotion. Peck’s interventions in many ways launched and framed the debate, offering an admirably balanced early attempt to convey concern about what he felt was the conspicuous absence of the discipline from important policy debates that it had much to offer across its disciplinary breadth and with its distinctively spatial perspectives and expertise (Peck, 1999; Peck, 2000). The key message was, as Massey later put it, that “we may be underplaying our hand” as a discipline (Massey, 2001: 12).

Others made similar points but more partially and notably more provocatively. Summarising those more extreme views, Anderson and Smith (2001: 7) write that to these more applied scholars the chief focus of concern was the “ostensibly narcissistic extremes” of the discipline’s ‘cultural turn’ over the preceding decade that “seem (to some) to be esoteric, inward looking and apparently oblivious to any ‘real’ world in which injustice abounds”. The post-modern and post-disciplinary currents of the cultural turn undoubtedly brought valuable new analytical richness to the discipline, opening up new research agendas and perspectives. Yet a persistent critique from some quarters of the discipline was that it had also turned swathes of academic human geography ever deeper inwards, subverting and distracting it into “an elaborate language game written by and for a tiny minority of participants” (Hamnett, 1997). Real world research problems that geographers could talk to and affect, it was argued, were being drowned out by “fuzzy conceptualization” (Markusen, 1999) where clear analysis, empirically tested theorisation and benefits beyond the academy were lost amidst “a thicket of linguistic ‘cleverness’ and epistemic relativism” (Martin, 2001: 196) that left some pleading for a “geography without origami” (Hamnett, 2014).

Some went further still, critiquing not only the message but more fundamentally the research substance. Martin argued unequivocally that “much contemporary social and economic geography research renders it of little practical relevance for policy, in some cases of little social relevance at all” (Martin, 2001:189). Dorling and Shaw described the discipline of human geography as “an intellectual safety net, an academic refugee camp” where cultural geographers “feel valued in their irrelevancy” (Dorling and Shaw, 2002: 638) within a discipline that does not value engaged work – their provocative advice to fellow academic geographers being to switch disciplines if ’useful’ research is a research objective. Whilst seeking no doubt to stir positive debate and change, these interventions created an unhelpfully crude and emotive tinderbox that hung over the debate as much as it may have stimulated it, disabling potentially useful analytical conversation by lambasting other types of geography into what were painted as lesser corners of the discipline. Some took aim further still at left-leaning academics themselves who, some argued, had sold out from the revolutionarily Marxist zeal of the 1970s to a form of insular journal-based “paper radicalism” (Pain, 2006: 253). The consequences, it was argued, were a dangerous retreat and separation of academia from the real world injustices that these scholars railed against (Hamnett, 2003) as well as a blunting of the critical edge to their intellectual analyses of these issues (Peck, 1999; Philo and Miller, 2014). Many, rightly, shared Imrie’s view that the zeal and tone of some of the policy advocates ought to be handled with caution in order to “guard against diminution of the intellectual integrity of the subject, or, what I perceive to be, the belittling of particular epistemological positions, modes of inquiry, and forms of expression and writing” (Imrie, 2004: 698). Massey, for instance, summarised the tone of Dorling and Shaw’s provocative interjection as a mixture of “persistent misunderstanding (wilful?), a scatter of insults (gratuitous) and a total inability to detect irony”, even if they claimed to agree with much of their general sentiment that the discipline could do more to make use of its potential contributions to policy (Massey, 2002: 645). In response, personally emotive and professionally invested positions became entrenched and antagonistic. The debate quickly became fractured and bent in myriad directions.

Some denied a problem of relevance existed at all, pointing either to particular policy related studies (Banks and McKian, 2000; Fuller and Kitchin, 2004; Imrie, 2004) or insisting that a broader view of ‘relevance’ would in fact bring most academic geography into scope (Ward, 2005: 316-7). Pacione (1999) offered an interesting historical perspective here, arguing that whilst there may well be an issue with the policy relevance of academic human geography in the mid-2000s that this may well be in the natural cyclical order of things. The discipline, as with all disciplines, moves he argued in cycles between pure and applied emphases depending in significant part upon the nature of the external economic and socio-political context – economic booms enabling greater emphasis on more abstracted pure research whilst economic crises generating pressures towards more applied problem-solving scholarship.

Others agreed with the view that there was an issue and sought explanations or justifications. A widespread view was that academia holds a low valuation of ‘applied’ as compared to ‘pure’ research and that this creates, in various ways, significant challenges to greater academic engagement with policy (Dorling and Shaw, 2002; Martin, 2001; Peck, 1999; Ward, 2005). Hence, whilst some critiqued what they saw as the detached theorising of some parts of the discipline into the academic echo chamber of journals and conferences, Castree argued in response that critical geography had simply “grown fat” (Castree, 2002: 106) by serving up what the rules of the academic game demanded, for which more applied scholars ought to be neither surprised nor blameful.

Interwoven too were a raft of counter-currents where colleagues sought to dilute or resist pleas for more policy relevant geographic research. Some claimed policy makers were disinterested in geographical knowledge (Henry et al., 2001) whilst many (rightly) worried about possible co-option of academic impartiality and integrity by politically motivated policy makers (Imrie, 2004; Staeheli and Mitchell, 2005; Owens, 2005). Far from new concerns, these views were reminiscent of Harvey’s Marxist-inspired fears in the equivalent debate of the mid-1970s that academic human geographers not “prostrate ourselves and prostitute our discipline before ‘national priorities’ and ‘the national interest’” that serve only to maintain – rather than fundamentally disrupt – existing unequal relations of power and wealth (Harvey, 1974: 22). Others felt the opposing pressure and sought to resist what they saw as the creeping instrumentalization of academia towards external agendas and the perceived squeezing out of ‘pure’ research. These types of ‘pure’ research, it was argued, ought to be the appropriate focus of (geography) academics (Burgess, 2005; Smith, 2010) in order to leverage what was described, in a Foucaultian sense, as the “destabilizing effects of knowledge” for others to then make use of in their policy engagements (Imrie, 2004: 702; Mitchell, 2004).

Several complained about what were often described as seemingly impossibly increased demands placed upon academics within modern higher education (Burgess, 2005; Pain et al., 2011; Pollard et al., 2000), a trend that has only escalated further since the 2000s. “Hero researchers” might stay afloat amidst the seemingly ever increasing demands of modern academia to excel in all directions, Owens argued (Owens, 2005: 290), but most would drown. Others looked wider beyond the academy, arguing that the shifts rightwards in the political and economic landscape beyond academia since the 1980s had left an external context unsympathetic if not hostile to many of the discipline’s concerns for justice, equality and progressive change within human geographic scholarship (Castree, 2002; Imrie, 2004). Somewhat distinct, others sought to divert the energy of the debate towards their own desired specific intellectual variant of ‘policy geography’ – the ‘in here’ politics of Castree to transform higher education itself (Castree, 1999), ‘public geographies’ (Ward, 2006), discourse studies (Rydin, 2005), and, at the other extreme, randomised control trials for area-based initiatives (Cummins, 2003). Whilst silently emphasising the potential for plurality the effect was the further fragmentation and disabling of potentially productive inclusive dialogue.

In summary, the policy geography debate of the 2000s contained an abundance of valuable individual colours, layers and themes. But on stepping back from the canvas it is clear that the picture as a whole remains fragmented and without coherence, engagement or agreement. As such, the debate as a whole – despite the many valuable contributions within it – lacks holistic critical reflection, wastes valuable learnings and fails to exploit its potential for disciplinary progress. The remainder of the article responds to that need. The discussion steps back for the first time to our knowledge from its noisy canvas to offer a valuable synthesis of its key substantive messages and, via the creation of an original inclusive framework to think about what ‘policy geographies’ is and might be, to highlight its key but thus far lost analytical contributions to the discipline that remain as relevant today.

Reflecting back on the debate: key messages lost in the noise

Taking an overarching look back over the literature several themes recur – knowledges, values, incentives, constraints, motivations, audiences, purpose, truths, objectives, possibilities. Whilst diverse in their specific position within the debate these themes can be understood in relation to two long-standing and inter-related conceptual discussions around the nature of ‘policy’ and of academic ‘geography’ respectively (Harvey, 1974).

The (mis)reading of ‘policy’ is a key implicit source of disagreement within the policy geographies debate of the 2000s. It is at the same time a source of inclusive potential once reconsidered in terms of the discipline’s full range of possible contributions to the policy process. A foundational source of disagreement flows from the lack of specificity around the nature of what scholarly policy engagements are or, more helpfully, can be. Somewhat ironically, for some ‘critical scholars’ the depiction of ‘policy work’ slips into crude accusations of uncritical, atheoretical empirical work that responds blindly to the whims and questions of policy makers (Burawoy, 2005b; Fuller and Kitchin, 2004; Imrie, 2004). Ideas of servile contractual and consultancy based relationships around already narrowly pre-defined analyses and evaluations are common targets, mirroring the crude caricatures of critical geographies painted by some more applied colleagues discussed above. Moreover, these empirical analyses it is argued serve to simply reinforce existing power structures and injustices, in contrast to the alleged intrinsically disruptive and progressive nature of ‘critical geography’ (Fuller and Kitchin, 2004; Imrie, 2004). A more nuanced reading of ‘policy’ highlights the deficiencies of this position. Johnston and Plummer (2005) helpfully outline a range of iterative and interacting phases to the policy process from the initial identification of an issue through to the design and implementation of a policy intervention to affect that issue and, eventually, an evaluation of that intervention. This breadth of the policy process into which geographers might seek to engage helpfully opens up the debate by recognising that ‘policy geography’ might more usefully be conceived in a multi-dimensional sense as different types of potential ‘policy geographies’ dependent upon the nature and timing of the scholarly interaction within this multi-stage policy process. In the context of this richer understanding of ‘policy’ the narrowly instrumental and servile caricature of ‘policy geography’ painted by some critical geographers represents just one form of policy scholarship that is described variously in the literature as ‘downstream’, ‘policy-directed’ or ‘shallow’ (Peck, 1999; Peck, 2000), and even here a disparagingly partial view of what such downstream activities are and can affect (Martin, 2001; Peck, 1999).

More pertinent to the present argument are the earlier ‘upstream’ phases of the policy process overlooked by these critical scholars given that the possibilities of this ‘deep’ upstream policy geography negates critiques of instrumental servility, seeking as it does to reconceptualise, reframe and reshape policy issues, questions and making (Martin, 2001; Massey, 2001; Peck, 1999; Peck, 2000; Rydin, 2005). Instead, it is these deep upstream contributions of spatialized policy reimaginings that are emphasised by key scholars such as Peck and Massey as the most powerful way in which the discipline can contribute its unique theoretical and conceptual spatial insights to more fully reconceptualise policy agendas – their issues, nature, problematization and possible solutions – in order both to enhance and gain greater intellectual control over policy processes (Massey, 2001; Peck, 1999; Peck, 2000). As Massey argues, “it is in the formulation of the questions themselves that the most crucial aspects of social science knowledge can be brought to bear. What social science might do more radically is reformulate questions, or point to (the many) questions which ought to be being asked but aren’t” (Massey, 2000: 132). Thus, any depiction of ‘policy geography’ as necessarily servile, atheoretical and ‘less-than-academic’ comes to be seen not only as a uncritical and unwarranted partial reading of what that is and can be but also that is in neglect of the significant upstream conceptual contributions that critical geographical scholarship can contribute to the policy process.

Massey and Peck articulate these key ideas most clearly perhaps within the debate (Massey, 2001; Peck, 1999). Focusing on ideas of “space, and the possibilities for its reimagination” (Massey, 2001: 14) with respect to policies to tackle spatial poverty and inequality, Massey for example argues powerfully that observed spatial distributions of outcomes are not themselves created by spatial processes but rather as a result of inequalities in wider aspatial socio-economic relations – spatial inequality both is and is not a spatial issue. Massey argues that the problem with policy thinking In this context is one of “spatial fetishism” (Massey, 2001: 16) – a misplaced obsession with geographical scales, surfaces and boundaries when the causal processes of persistent geographical poverty and inequality rest instead on a relational view of space rooted in the power-infused webs of social relations across and between places and people. Due to this spatial misreading, the types of spatially rooted local and area-based interventions popular with policy makers prove ill equipped to tackle those aspatial causal processes that underlie persistent patterns of spatial poverty and inequality. However, engaging with policy debates on the issue Massey expressed “gloom not so much at the regional inequality itself as at the whole conceptual framing of the question…[yet] the import of our philosophical and conceptual arguments was nowhere to be seen” (Massey, 2001: 7-8). As with many critical geographers, Peck pleads in response that what is urgently needed is the type of critically rooted “deep, engaged and incisive” (Peck, 2000: 256) policy analysis that “questions the parameters, presumptions and premises of policies, rather than just their outcomes” (Peck, 1999: 133).

Language, ideas, understandings of issues and their causes – and the distinctively geographical dimensions to these conceptualisations across many fields of policy activity – in these ways become central to what policy geographies can and should be: “[G]eographical imaginations…are not simply mirrors; they are in some sense constitutive figurations; in some sense they ‘produce’ the world in which we live and within which they are themselves constructed” (Massey, 2001: 10). The focus of key upstream policy geographies for Massey, as for Peck, is what sense circulates and prevails within the policy process and how we as academic geographers can reconceptualise and reframe those understandings to enhance policy making and outcomes. These perspectives move the debate towards a Foucaultian inspired recognition of the relevance to policy geographies properly conceived of key linkages between knowledge, power, discourse and ‘truth’ (Pinch, 1998), linkages that some applied protagonists in the debate may mistakenly see as unduly esoteric. The impact of these richer lines of enquiry is to beneficially fracture artificial binaries erected during the debate around the nature of what ‘policy geographies’ is and can be, opening out ‘policy’ to encompasses the full range of phases of the policy process from upstream (re)framing interventions through to downstream directed responses (Johnston and Plummer, 2005) and ‘geography’ to incorporate the full breadth of the discipline.

These openings bring into question the frequently presented dichotomy between ‘pure’ and ‘applied’ research (Fuller and Kitchin, 2004). Many questioned the veracity of this ‘pure’ versus ‘applied’ binary before the debate of the 2000s (Coppock, 1974) as well as within it (Markusen, 1999: 880; Massey, 2001; Massey, 2002; Pain, 2006; Peck, 1999), even if most continued to agree that mainstream academia continues in various ways to elevate high theory (Castree, 2002; Martin, 2001; Staeheli and Mitchell, 2005; Peck, 2000). In contrast, critically engaged applied scholars talk instead of a self-reinforcing virtuous feedback cycle between their theoretical and policy research where neither are separate nor superior (Lee, 2002; Martin, 2001; Massey, 2001; Massey, 2002; Pain, 2006; Pain et al., 2011; Peck, 1999; Staeheli and Mitchell, 2005: 365). Rather, these different types of scholarship are described as “different sides of the same coin” (Peck, 1999: 132) in a “moving-between” (Massey, 2002: 645) of the abstracted, big picture theoretical and the detailed, nuanced and contextualised empirical rigour of the policy minutiae that operates dialogically and reflexively to strengthen the other. In doing so the ‘pure’ work of academic high theory is subjected to the rigour and specificity of the empirical and policy work, sharpening and deepening that theoretical work by rendering it “theory as an embedded mode of being in the world” (Massey, 2001: 13-14) rather than what Markusen sees as the detached and loose ‘fuzzy theorization’ of too much current geographical scholarship (Markusen, 1999: 880).

Though lost at the time amidst the frenzied noise of the exchanges, when reflecting critically over the policy geographies debate of the 2000s it is this richness and flexibility in the breadth and depth of what ‘policy geography’ is and can be that is the key learning to take forwards if we are collectively to develop a more productive set of understandings, exchanges and scholarly practices around policy engaged geographical scholarship. The following section seeks to advance that ambition through the presentation of an original analytical framework within which to encourage the discipline to think holistically, inclusively and flexibly about the full range of what ‘policy geographies’ can be to scholars and scholarship right across the discipline.

Moving forwards with policy geographies: a holistic and inclusive disciplinary framework

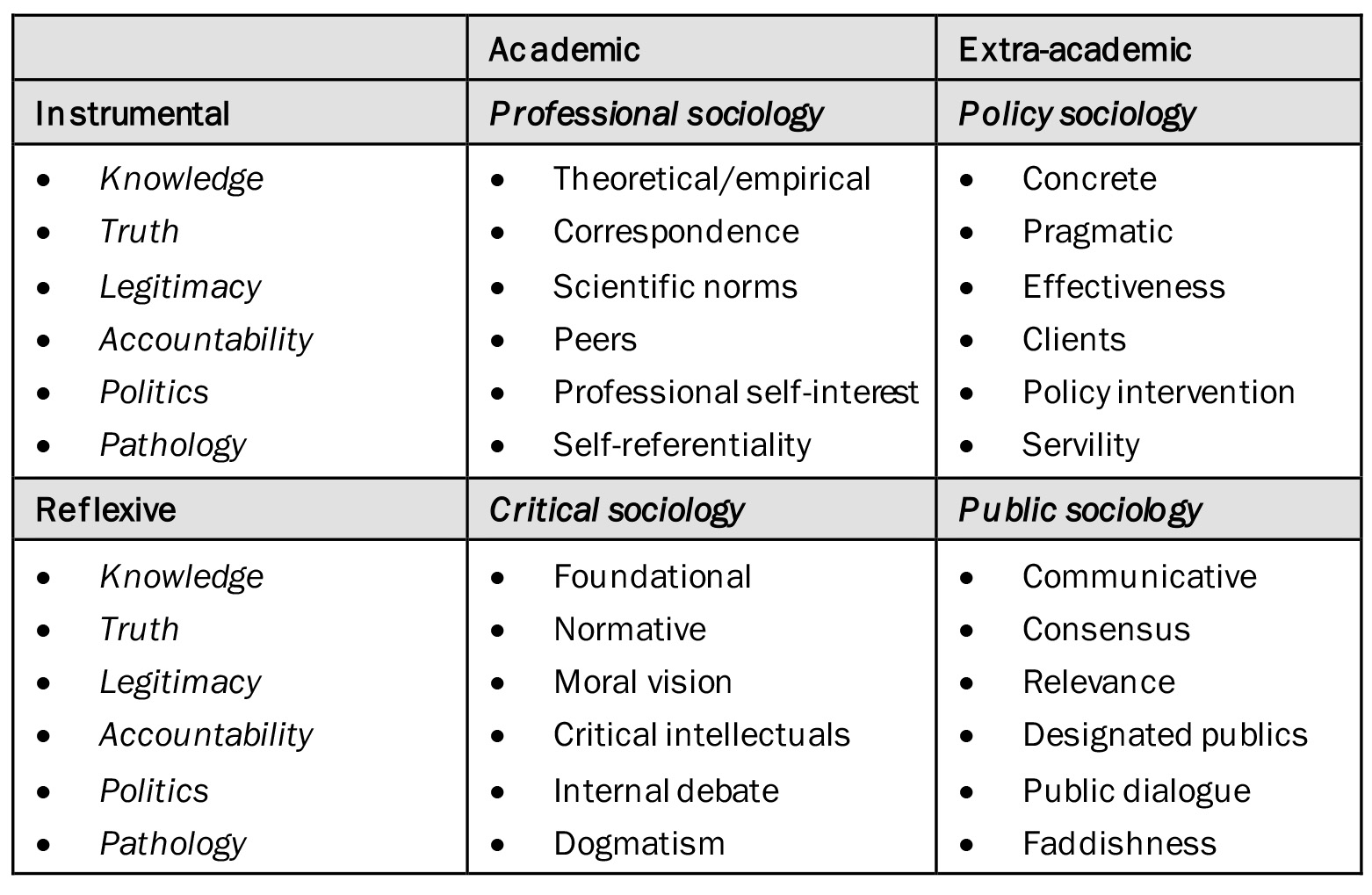

Amongst the divergent voices of the policy geographies debate it is striking how little systematic analytical thinking took place. Brought into the debate by Ward’s related discussion of ‘public geographies’ (Ward, 2006), one analytically helpful way into this task is provided by Burawoy’s four proposed types of sociological knowledge in parallel debates within the sociological literature: professional sociology of the academic discipline as an occupation and sector; critical sociology that represents the theoretical intellectual foundations of academic sociological thinking; public sociology that engages in dialogue and engagement with a range of publics directly or indirectly; and, most relevant to the present focus on policy geographies, policy sociology that engages with and seeks to affect policy makers and the policy process (Burawoy, 2004a; 2004b; 2005a; 2005b).

Table 1 reproduces Burawoy’s typology. His depiction of these four knowledges differentiates them firstly according to whether their knowledge is within or without academia and secondly according to whether it can be considered as instrumental or reflexive knowledge. Policy sociology, for instance, is described in the top right cell as instrumental knowledge beyond academia. Within each cell each type of knowledge is then summarised along six different dimensions that it is suggested define their distinctiveness as a type of sociological knowledge – knowledge, truth, legitimacy, accountability, politics and pathology.

Table 1: Burawoy’s typology of sociological knowledges

Burawoy’s framework helpfully encourages a structured analytical reflection on the nature of policy sociology as well as its distinctiveness from other forms of sociological knowledge. Always a risk in ambitious heuristic exercises such as this, it is however limited as an analytical framework both the validity of its caricatures as well as its implied separations between those caricatures. Focusing on this paper’s key interest in policy knowledges, in its depiction of policy sociologies Burawoy plays into the unrealistically simplistic and unnecessarily pejorative portrayal of policy scholarship critiqued above as servile, unthinking, directed and empirical across its dimensions. In particular, Burawoy suggests that policy geographies are: an instrumental practical concrete knowledge of specific, pre-defined topics rather than having any place for critical thinking or dialogical coproduction with policy makers; that the truth of that policy scholarship is defined by what is politically pragmatic rather than what is right; its legitimacy is based on more effectively delivering, or indeed simply legitimating, pre-existing policies or policy thinking rather than having any place for rethinking, reframing or critiquing issues or policies; its accountability is to policy makers contractually, ceding independence of the framing of questions and policy processes; and with a pathology of servility to potentially ethically questionable, or even conflicting, policy agendas and ends (Burawoy, 2004a; 2004b; 2005a; 2005b).

Hence, whilst Burawoy’s approach offers a helpful general attempt to frame analytically key ideas of the debate, his partial portraitures of these alternative knowledges in order to differentiate them within the framework results in an artificially narrow and contorted caricature of policy knowledges that it is of limited analytical value in thinking critically about what policy geographies is and can be. However, looking back across the policy geographies debate after the event and with a degree of analytical distance highlights that it is possible to identify constructive overarching messages that make possible an analytical view of policy geographies that is inclusive, holistic and flexible to the plurality of what that is and can be across the discipline – even if those messages were lost in the noise of the debate at the time.

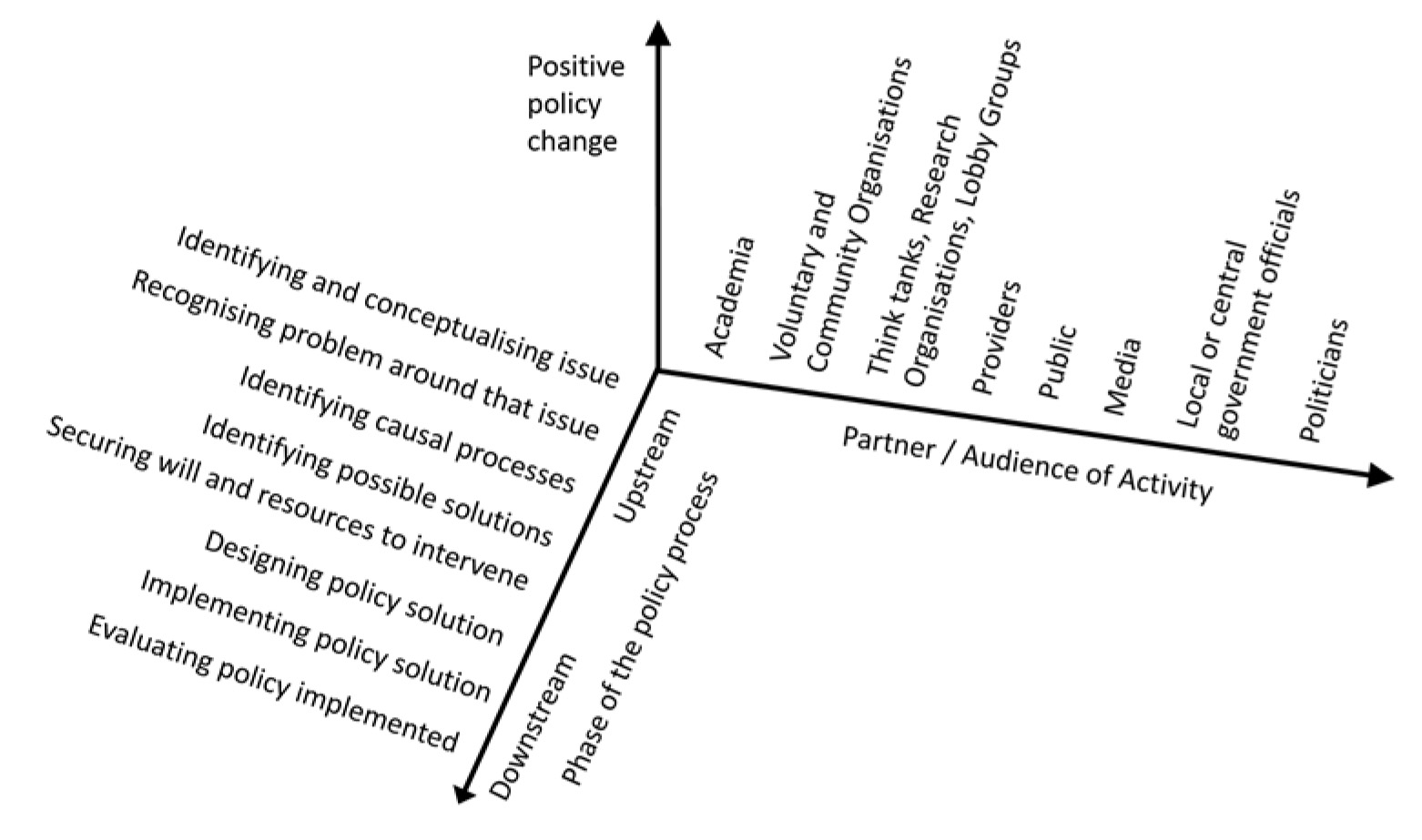

Figure 1 presents a proposed analytical framework to this end, taking forwards concretely for the first time in the literature a response to those isolated voices within the debate of the 2000s that both thought more analytically about the debate’s key messages and possibilities and were sufficiently open to recognise the centrality of pluralism within that analytical thinking and scholarly practice around policy geographies (Pollard et al., 2000). Across one axis on its base lie the key phases of the full policy process into which geographical scholars might engage, amended from those suggested by Johnston and Plummer (2005). Importantly, this proposed policy process encompasses those ‘upstream’ phases of the policy process that relate to the scholarly role in understanding, (re)conceptualising and (re)framing the later phases of the policy process as well as those ‘downstream’ phases themselves that focus more specifically on the design, implementation and evaluation of particular policies. Along the other axis of its base are the main types of partners or audiences that geographical scholars might engage with in order to pull through the potential contributions of their academic research and expertise into those phases of the policy process. These encompass inclusively the ‘in here’ policy geographies of Castree (1999; 2002), the public geographies of Ward (2006), Peck’s ‘high policy’ work with civil servants and politicians (Peck, 1999) as well as the wide range of voluntary, community, media or campaigning organisations at local and national levels that academics can and do work with to seek to affect policy positively.

Both axes emphasise inclusivity and equality such that no element on either axis is seen as superior to any other. Rather, each axis represents categories of different possibilities rather than any continuous scale of progressing/decreasing in any direction. Rather, all activities are understood as equally valid and valuable attempts to maximise the value and potential contributions of the range of disciplinary expertise to the range of key phases of policy processes ‘out there’ in the real world beyond our internal scholarly conversations with each other about those policy processes . Taken together, therefore, the base of the framework is conceived across these two dimensions as a mesh of different but equal approaches that policy geographers can and might adopt to seek to use their academic expertise to benefit policy.

Figure 1: A holistic and inclusive framework of – and for – policy geographies

The vertical axis of the framework represents positive policy change and this is suggested to be a continuous axis with increasing amounts of positive change as one moves upwards along the axis. Each of these terms benefits from clarification. ‘Positive’ is presented as inevitably subjective across scholars, hence it is for each person to decide what for them constitutes progress in these activities; no externally imposed definition is considered viable or helpful. ‘Policy’ is conceived in a broad sense such that whilst it may relate to direct scholarly influence on phases of the policy process it may also be understood in terms of indirect influence through, for example, work with media, public or voluntary organisations that affects the wider policy environment within with policy decisions interact and are informed and constrained. And, finally, ‘change’ pushes the academic community to seek to make a tangible contribution to policy – in whatever way and however small. This is considered important to focus minds on closing the gap between policy potential and its realisation within our scholarship and to challenge the view from some that holding a progressive intent or describing but not affecting change within that scholarship is sufficient (Mitchell, 2004; Staeheli and Mitchell, 2005: 363). Hence, the framework is inclusive and pluralistic. But with that also deliberately challenging. For in doing so this implies reciprocal responsibilities for scholars to make efforts to pull through the policy potential of their scholarship – however they best see fit in light of their particular type of geographical scholarship – alongside the recognition within the framework that those potential contributions fall across the full range of the discipline.

Thus, across its axes Figure 1 becomes a three-dimensional space within which policy geographers can think about and locate themselves according to the nature of their policy engagement (as depicted by their position on the two-dimensional base) as well as the influence of their engagement in affecting positive policy change (as depicted by their movement upwards along that vertical axis). Two points are worth noting. First, there is no a priori claim made here as to which type of policy engagement (i.e. location on the base) is either superior or most likely to generate positive policy change upwards along the vertical axis. Second, it seems likely in practice that both the nature of engagements (across the base) and the extent of their policy impacts (upwards along the vertical) will be multiple and variable rather than individual and discrete. Hence, the idea visually of heat maps seems more appropriate than that of single points in the framework’s three-dimensional space. For example, in terms of their policy engagements a scholar may work with third sector organisations, lobby groups and policy makers to rethink the understanding of an issue’s nature, causal processes and potential solutions. Representing this visually across the two-dimensional dimensions of Figure 1 generates a shaded area covering those intersecting elements and not a single discrete location. Similarly, although working across all of those interesting elements it may be that they each achieve different levels of positive policy change. Visually this converts what was a two-dimensional shaded area at the base into a curved plane in three-dimensional space where the differing heights of that surface reflect the differing impacts on policy made with each type of policy engagement undertaken.

To be clear, this is not to suggest that policy geographers ought in our view to start graphing their various policy engagements and quantifying the area under their curves to create some sort of ‘impact metric’ (e.g. the area under the curved plane) equivalent to those now commonplace in relation to publication citations. Rather, it is presented simply as a heuristic device to explain and enable understanding of the framework and its ideas. Nor is it to suggest that taking our scholarship beyond the academy to benefit policy is easy or straightforward, or that all of us should be doing it all of the time. The challenges to this within both academia and policy processes are real and significant, despite the continued sectoral drive for academics to ‘make a difference’. Within UK academia, for example, achieving ‘impact’ has become a powerful and pervasive addition to the way in which grants are awarded, universities are assessed and ranked, and hence how academics are managed. For many voices in this debate this may represent a long overdue revaluation by the sector of a more engaged form of academia. Although there is some truth in this, it is also the case that the narrow, problematic, instrumental and managerial operationalisation of the ‘impact’ agenda in UK academia (Pain et al., 2011) offers ample fuel to the fires of those already critical voices resisting efforts towards greater external engagement of their scholarship.

It is to argue, however, that what is required is “a way to talk about relevance that avoids the dualism between theory and practice and that eschews the temptation to imply that some research traditions are less amenable to relevance than others” (Staeheli and Mitchell, 2005: 359). To this end the present argument has sought to excavate the key lessons lost amidst the noise of the frenetic and emotive policy geographies debate of the 2000s in order to emphasise the plurality of what policy geographies is and can be for the discipline and its scholars, and to highlight in doing so the potential and relevance of policy geographies thus conceived right across the breadth of the discipline. Certainly, there are ways that both the academic and policy sectors can further enable and recognise such work. But, and as other have argued previously (Castree, 2002; Massey, 2000), in that context the harder challenge may instead be for ourselves in the practice of our scholarship – whether we as academic geographers wish to make use of our wide-ranging expertise and potential contributions to policy and to conceive of our role and value in terms larger than our university’s never-ending demands for the next journal article and grant application?

Dr Adam Whitworth, Senior Lecturer in Human Geography, Programme Co-Director MSc Applied GIS, Departmental REF Impact Lead, Department of Geography, University of Sheffield. Email: adam.whitworth@sheffield.ac.uk

Anderson, K. and Smith, S. (2001) Editorial: Emotional geographies. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 26, 7-10. CrossRef link

Banks, M. and MacKian, S. (2000) Jump in! The water’s warm: a comment on Peck’s ‘grey geography’. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 25, 249-254. CrossRef link

Burawoy, R. (2004a) The world needs public sociology. Sosiologisk tidsskrift, 12, 255-272.

Burawoy, R. (2004b) Public sociologies: contradictions, dilemmas, and possibilities. Social Forces, 82, 4, 1603-1618. CrossRef link

Burawoy, R. (2005a) The critical turn to public sociology. Critical Sociology, 31, 3, 313-326. CrossRef link

Burawoy R (2005b) 2004 American Sociological Association Presidential address: For public sociology. The British Journal of Sociology, 56, 2, 259-294. CrossRef link

Burgess, J. (2005) Commentary – Follow the argument where it leads: some personal reflections on ‘policy-relevant’ research. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 30, 273-281. CrossRef link

Castree, N. (1999) ’Out there’? ‘In here’? Domesticating critical geography. Area, 31, 1, 81-86. CrossRef link

Castree, N. (2002) Border geography. Area, 34, 1, 103-108. CrossRef link

Coppock, J. (1974) Geography and public policy: challenges, opportunities and implications. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 63, 1-16. CrossRef link

Cummins, S. (2003) Observation to experimentation: One prescription for a geography of public policy. Area 35, 2, 220-222. CrossRef link

Dorling, D. and Shaw, M. (2002) Geographies of the agenda: public policy, the discipline and its (re)‘turns’. Progress in Human Geography, 26, 5, 629-646. CrossRef link

Fuller, D. and Kitchin, R. (2004) Radical theory/critical praxis: academic geography beyond the academy? In: Fuller, D. and Kitchin, R. (eds) Radical theory/critical praxis: making a difference beyond the academy? Vernon and Victoria, BC: Praxis (e)Press, pp. 1-20.

Hamnett, C. (1997) The sleep of reason? Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 156, 127-128. CrossRef link

Hamnett, C. (2014) The emperor’s new theoretical clothes, or geography without origami. In: Philo, C. and Miller, D. (eds) Market killing: What the free market does and what social scientists should do about it. Routledge: London: 158-169.

Hamnett, C. (2003) Contemporary human geography: fiddling while Rome burns? Geoforum, 34, 1-3. CrossRef link

Harvey, D. (1974) What kind of geography for what kind of public policy? Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 63, 18-24. CrossRef link

Henry, N., Pollard, J. and Sidaway, J. (2001) Beyond the margins of economics: geographers, economists, and policy relevance. Antipode, 33, 200-207. CrossRef link

Imrie, R. (2004) Urban geography, relevance, and resistance to the ‘policy turn’. Urban Geography, 25, 8, 697-708. CrossRef link

Johnston, R. and Plummer, P. (2005) Commentary – What is policy-oriented research? Environment and Planning A, 37, 1521-1526. CrossRef link

Lee, R. (2002) Geography, policy and geographical agendas – a short intervention in a continuing debate. Progress in Human Geography, 26, 5, 627-628. CrossRef link

Markusen, A. (1999) Fuzzy concepts, scanty evidence, policy distance: the case for rigour and policy relevance in critical regional studies. Regional Studies, 33, 9, 869-884. CrossRef link

Martin, R. (2001) Geography and public policy: the case of the missing agenda. Progress in Human Geography, 25, 2, 189-210. CrossRef link

Massey, D. (2000) Editorial: Practising political relevance. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 25, 2, 131-133. CrossRef link

Massey, D. (2001) Geography on the agenda. Progress in Human Geography, 25, 1, 5-17. CrossRef link

Massey, D. (2002) Geography, policy and politics: A response to Dorling and Shaw. Progress in Human Geography, 26, 645-646. CrossRef link

Mitchell, D. (2004) Radical scholarship: A polemic on making a difference outside the academy. In: Fuller, D. and Kitchin, R. (eds) Radical theory/critical praxis: making a difference beyond the academy? Vernon and Victoria, BC: Praxis (e)Press: 21-31.

Mitchell, K. (2006) Writing from Left Field. Antipode, 38, 205-212. CrossRef link

Owens, S. (2005) Commentary – Making a difference? Some perspectives on environmental research and policy. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 30, 287-292. CrossRef link

Pacione, M. (1999) Applied geography: in pursuit of useful knowledge. Applied Geography, 19, 1-12. CrossRef link

Pain, R. (2006) Social geography: seven deadly myths in policy research. Progress in Human Geography, 30, 2, 250-259. CrossRef link

Pain, R., Kesby, M. and Askins, K. (2011) Geographies of impact: power, participation and potential. Area, 43, 2, 183-188. CrossRef link

Peck, J. (1999) Editorial: Grey geography? Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 24, 131-135. CrossRef link

Peck, J. (2000) Jumping in, joining up and getting on. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 25, 255-258. CrossRef link

Philo, C. and Miller, D. (2014) (eds) Market killing: What the free market does and what social scientists should do about it. London: Routledge.

Pinch, S. (1998) Knowledge communities, spatial theory and social policy. Social Policy and Administration, 32, 5, 556-571. CrossRef link

Pollard, J., Henry, N., Bryson, J. and Daniels, P. (2000) Exchange – Shades of grey? Geographers and policy. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 25, 243-248. CrossRef link

Rydin, Y. (2005) Geographical knowledge and policy: the positive contribution of discourse studies. Area, 37, 1, 73-78. CrossRef link

Smith, K. (2010) Research, policy and funding – academic treadmills and the squeeze on intellectual spaces. The British Journal of Sociology, 61, 1, 176-195. CrossRef link

Staeheli, L. and Mitchell, D. (2005) The complex politics of relevance in Geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 95, 2, 357-372. CrossRef link

Ward, K. (2005) Geography and public policy: a recent history of ‘policy relevance. Progress in Human Geography, 29, 3, 310-319. CrossRef link

Ward, K. (2006) Geography and public policy: towards public geographies. Progress in Human Geography, 30, 4, 495-503. CrossRef link

Ward, K. (2007) Geography and public policy: activist, participatory, and policy geographies. Progress in Human Geography, 31, 5, 695-705. CrossRef link