Abstract

Social prescribing is a current UK social policy phenomenon but to what extent does it represent a substantive change in the way policymakers think about services for people with multiple and complex needs? I draw on several local studies of social prescribing initiatives to argue that cautious optimism is merited: through the idea of social prescribing ‘plus’ key actors in a number of localities have embraced the principles of asset-based working and collaborative innovation to achieve real change in policy and practice. However, policy interest in social prescribing cannot be decoupled from the public sector austerity and transformation agenda, and the true testing ground will be how local policymakers develop services in future: will they draw on the asset-based collaborative principles of social prescribing ‘plus’; or will it lead to expectations that people and communities do more for themselves without the necessary investment in this alternate model of welfare.

Introduction

Social prescribing has become something of a social policy phenomenon in the UK in recent years. If your local area hasn’t ‘got it’ already then you can be certain that key players from the local voluntary and community sector will be lobbying health and social care policymakers to get it up and running sooner rather than later. But is it just the latest ‘shiny new policy thing’ that will come and go before too or long or does it represent a more substantive change in the way policymakers think about the design and delivery of services for people with multiple and complex needs? This policy commentary draws on more than four years’ experience of research and evaluation with social prescribing initiatives at an area level, and parallel engagement with accompanying policy debates,1 to lay some groundwork for addressing this question. I do this by introducing the idea of social prescribing ‘plus’ and drawing together two emergent theoretical concepts – asset-based approaches to health and care; and collaborative innovation – to reframe social prescribing in the context of broader debates and competing paradigms of public administration. In the process, I hope to stimulate discussion and debate about social prescribing, its place in systems of health and social care service delivery, and the broader processes and principles of public service transformation.

What is social prescribing?

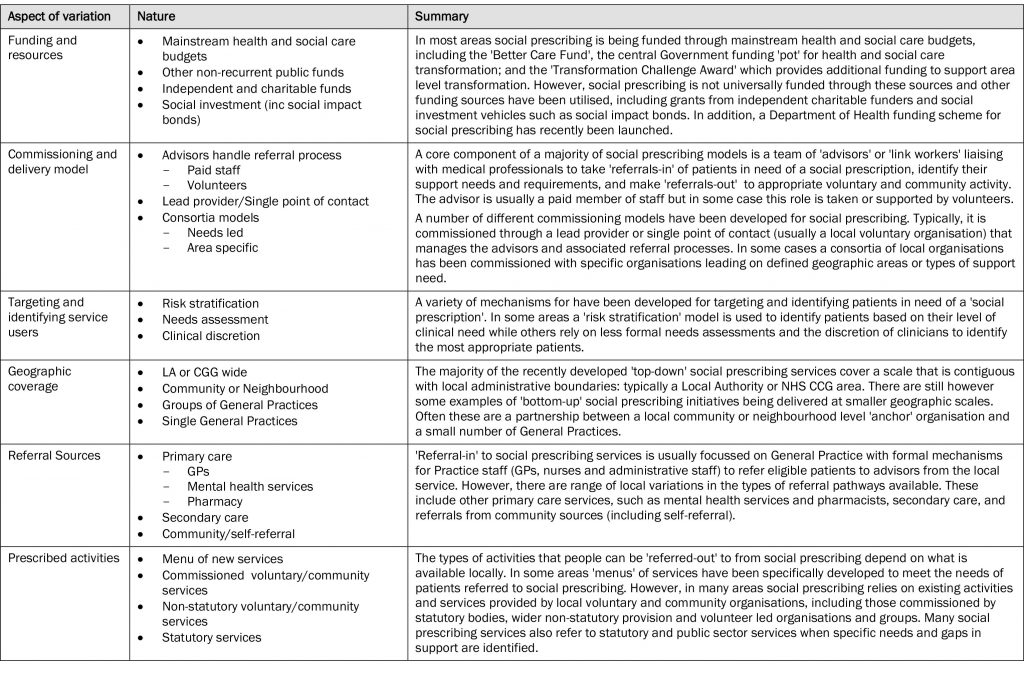

Social prescribing is a recent innovation in public health and social care services through which medical and care professionals – including General Practitioners (GPs), mental health practitioners, nurses and social workers – refer patients with complex health conditions to sources of social support provided by local voluntary and community organisations (South et al, 2008; Kimberlee, 2015; Dayson, 2017). The overarching aims of social prescribing are twofold: to reduce demand on primary, secondary and social care services; and to improve personal well-being and a wider range of social determinants of health such as isolation, self-esteem and social connectedness. In its early days social prescribing was typically delivered from the ‘bottom-up’ by local neighbourhood and community organisations and through volunteers working with single GPs or small groups of practices to link patients with existing activities and opportunities in their community. This work sometimes received small amounts of public funding but was not considered part of mainstream statutory service delivery. However, the period since 2012 has seen the emergence of social prescribing as a ‘top down’ policy agenda, with large ‘services’ increasingly being commissioned as part of area level health and social care integration and transformation programmes (see Hughes, 2017, for a broader discussion of this policy discourse). Despite this mainstreaming of social prescribing there remains considerable difference in the ways in which it is being implemented across the UK with local variations according to level and source of funding, model of commissioning, the targeting and identification of service users, geographic coverage, referral sources, and the breadth of ‘prescribed’ activities. A more detailed overview of these variations is provided in table 1.

Given the growing heterogeneity of social prescribing delivery models and the aims and assumptions that underpin them it is increasingly important to differentiate between approaches to social prescribing, in particular the breadth and depth of models developed in different localities and for different types of patient. An early attempt to codify approaches to social prescribing by Kimberlee (2015) laid them out on a continuum, from ‘light’ at one end through to ‘holistic’ on the other. However, as social prescribing has become part of mainstream commissioned services most approaches could be described as ‘holistic’, and there is a need to distinguish yet further between the these ‘holistic’ approaches. In response, the idea of social prescribing ‘plus’ has emerged from practice as a means of identifying the most extensive and embedded models and setting them apart from other ‘holistic’ approaches.

Although social prescribing ‘plus’ is an emergent concept that has not been formally defined, there are a number of key features and practices that set it apart from other approaches.

- Broad geographic coverage: the service will cover a large geographic area that is contiguous with a local authority or NHS Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) boundary.

- Multiple clearly delineated referral pathways from a variety of health settings: including from GPs and other practitioners at a practice level, statutory mental health services, and secondary care.

- A range of social prescribing specific services and activities are available: social prescribing service users are able to choose from a ‘menu’ of services that have been specifically developed for the service. These services will receive funding to ensure they can meet the demand from social prescribing service users. Where appropriate, service users will be supported to develop their own self-sustaining groups or activities.

- Significant long term investment of strategic funds across multiple service areas: local policymakers will view social prescribing as model for strategic commissioning with the voluntary sector and ensure funding is available over a long time period (three years or more) following a successful pilot phase.

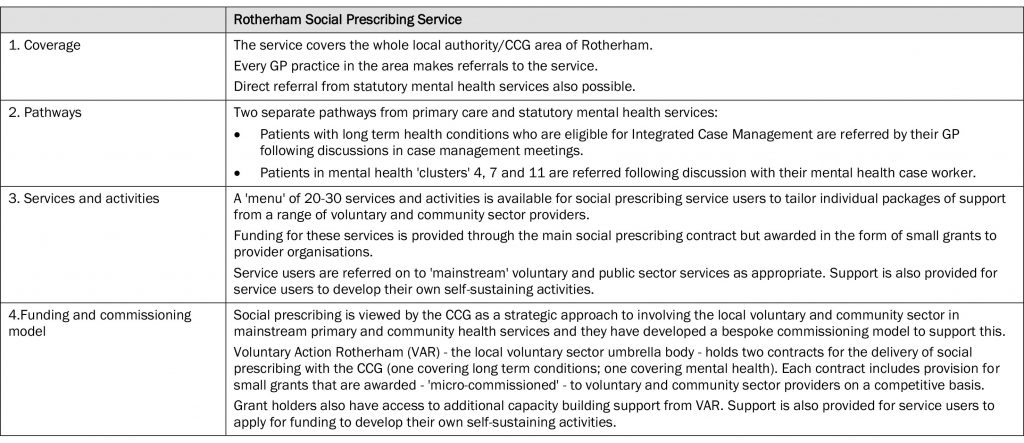

Although an example of social prescribing ‘plus’ would not be expected to exhibit all of these characteristics, it should exhibit a number in combination, and include a commitment to resourcing financially both the referral processes through which service users are identified and directed to support, and the services and activities to which they are referred. In areas where social prescribing ‘plus’ has been implemented it has necessitated step change in local commissioning practices that involve the local voluntary and community sector, from ad hoc and piecemeal awarding of grants and short term contracts, to a more strategic approach. An overview of one prominent example of social prescribing ‘plus’ – the Rotherham Social Prescribing Service – is provided in table 2 for illustrative purposes.

Framing social prescribing ‘plus’ from a policy perspective

Social prescribing is variously described as an ‘asset-based approach’ and a ‘social innovation’, but with limited engagement with the theoretical underpinnings of these terms or the processes associated with them. The following sections aim to provide some theoretical substance to the idea of social prescribing ‘plus’, first as an asset-based approach and then as an example of collaborative innovation, before bringing them together in a re-framing of social prescribing ‘plus’ as a model of policy innovation that combines both sets of ideas.

The possibilities and pitfalls of asset-based approaches to health and care

Although social prescribing is an important social policy development in and of itself, its rise to prominence needs to be understood in the context of the wider propagation of ‘asset-based’ approaches to health and care which have emerged in the past 10-15 years as a way of increasing equity in health. As a discourse it has permeated practice, policy and academia as a critical counterpoint to the (perceived) persistence of deficit-based approaches to health which focus on ‘problems’ that need to be ‘solved’ by health professionals and policymakers (Durie and Wyatt, 2013). The implicit assumption of deficit approaches is that individuals and communities do not have the necessary resources or expertise to address health problems themselves (Warr et al, 2013). In contrast asset-based approaches aim to promote and develop the capabilities and capacities that support good health and well-being whilst ameliorating the symptoms and consequences of poor health (Brooks and Kendall, 2013; Morgan and Zigilo, 2007). Morgan and Ziglio (2007: 18) describe a health asset as:

“…any factor (or resource), which enhances the ability of individuals, groups, communities, populations, social systems and/or communities to maintain and sustain health and well-being and help to reduce health inequalities. These assets can operate at the level of the individual, group, community and/or population as protective (or promoting) factors to buffer against life’s stresses.”

In essence asset-based approaches seek to redress the balance between meeting the needs of people and communities and nurturing their strengths (assets) in support of better health and well-being (McLean, 2011).

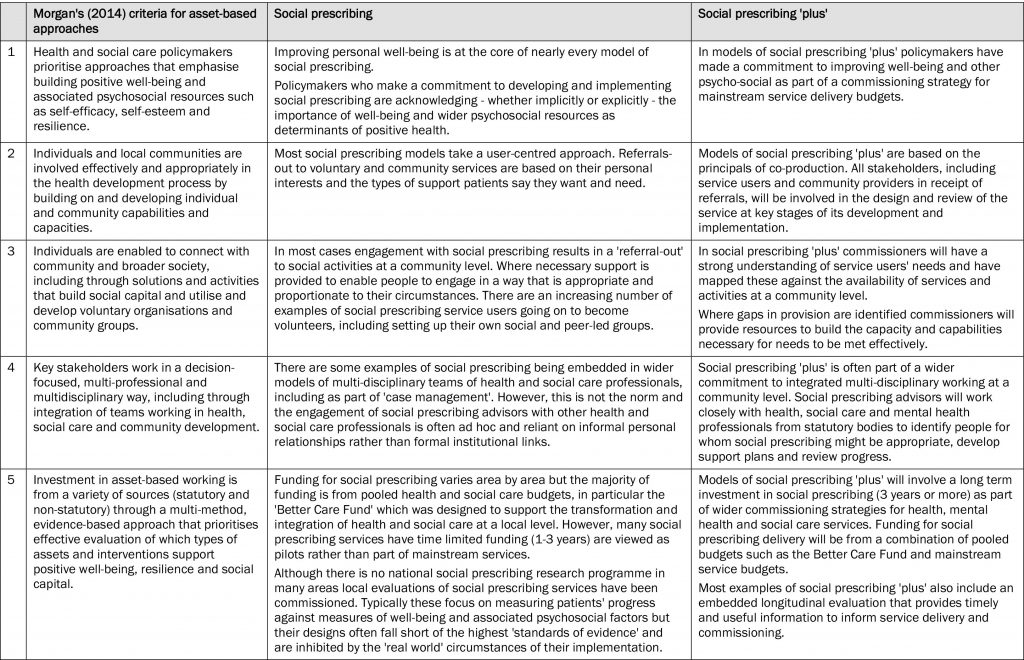

Although the rise to prominence of asset based approaches is evident in international, national and local policy developments (see e.g. WHO, 2012a and 2012b; NHS England, 2014; Department of Health, 2014; NHS North West, 2010) their practical implementation is in its infancy. They have typically been delivered through small projects or pilots rather than large programmes or system wide approaches to implementation. As such, evidence of their efficacy in addressing health inequalities is limited (Hopkins and Rippon, 2015) and very little has been written about the characteristics of a successful asset based approach. An exception is Morgan (2014), who proposed a set of principles against which the practical implementation of asset-based approaches can be assessed. An overview is provided in table 3 along with discussion of the extent to which different approaches to social prescribing meet these criteria. It indicates that whilst much of social prescribing practice mirrors the criteria of effective asset-based working it is social prescribing ‘plus’ that is most closely aligned with the principles Morgan (ibid) proposes.

Processes of collaborative innovation

Social prescribing can be described as a ‘social innovation’ in that it is a new idea that both addresses unmet social needs and works effectively to create social value (Mulgan, 2007; see also Dayson, 2017 for a broader discussion of social prescribing as a social innovation through which social value is created). However, to date, there has been little discussion of the processes of social innovation through which social prescribing has been adopted and diffused across the UK. The idea of collaborative innovation is helpful here because it highlights the importance of multi-actor collaboration during the development and implementation of a new policy (Hartley et al, 2013). In particular, it emphasises the involvement of ‘downstream’ actors, including voluntary and community organisations and service users, alongside ‘upstream’ policy stakeholders, in the creation and diffusion of novel and bold solutions to previously intractable and ‘wicked’ problems (Ansell et al, 2017). This requires a genuine commitment to multi-stakeholder involvement throughout the design and implementation of a policy: from understanding problems and challenges; to developing and testing new ideas; and implementing, adapting and diffusing successful approaches (see Sorensen and Torfing, 2015, for a broader discussion).

Proponents of collaborative innovation situate their arguments in a critique of the New Public Management approaches to public administration that have been predominant since the 1990s in many western democracies. Whereas New Public Management advocated quasi-markets through which public services were contracted out and imported other private sector mechanisms such as performance targets and performance related pay (see e.g. Hood, 1991; Osborne and Gaebler, 1992); collaborative innovation and associated New Public Governance approaches (see Osborne, 2006 and 2010 for a broader discussion) emphasise a more collaborative cross-disciplinary and inter-organisational approach focussed on complex (‘wicked’) problems and the development of bold new solutions to meeting them. Advocates of this type of approach argue that they are more likely to produce public innovations that lead to effective, efficient and higher quality services (Sorensen and Torfing, 2015).

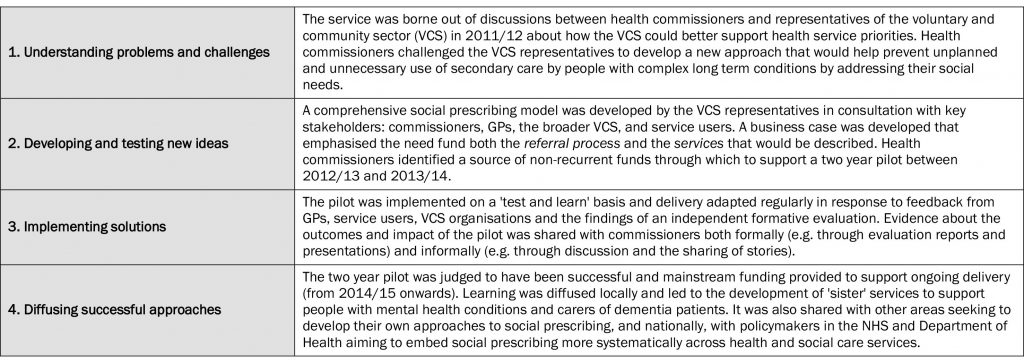

Table 4 draws on the case study of the Rotherham Social Prescribing Service to demonstrate the extent to which the development and implementation of social prescribing ‘plus’ exhibited the characteristics of collaborative innovation. This example highlights the extent of the collaborative processes involved in developing and implementing a social prescribing ‘plus’ model. It demonstrates how key actors in the social prescribing service were able to form a coalition of ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’ actors from the public, voluntary and community sectors to first understand problems and challenges associated with people multiple and complex long term conditions; then develop, test and implement series of new ideas for addressing their needs; before diffusing the approach to other areas of service delivery (mental health) and other parts of the country.

Reframing social prescribing ‘plus’ as a model of asset-based collaborative policy innovation

There are clear synergies between the principles of asset-based health and care and the ideas associated with collaborative innovation, many of which are manifest in the development and implementation of social prescribing ‘plus’ in the Rotherham example. I therefore propose a reframing of social prescribing ‘plus’ as a model of asset-based collaborative policy innovation based on the following principles.

1. Placing service users at the centre of the design and delivery of social prescribing

Service users play a central role in understanding needs – their own needs and the needs of others – and are provided with tailored support to address those needs. The ‘expertise’ of service users should be valued and recognised throughout the social prescribing development and implementation process, with regular opportunities to provide feedback and shape the future delivery of the service.

2. Harnessing and investing in voluntary and community assets through social prescribing

Voluntary and community organisations should be key stakeholders in the design and delivery of social prescribing services. Like service users they should be considered an asset whose expertise and insights are valued at all stages of the development and implementation process. There should also be a commitment to invest financially in organisations where their involvement in social prescribing requires them to deliver additional services or increase capacity in existing services. A further commitment to building the capacity of voluntary organisations involved in the delivery of social prescribing, including support for new user-led groups and activities to develop, will be essential if a voluntary and community asset base capable of supporting social prescribing is to be sustained.

3. Taking on board the needs and views of professionals involved in social prescribing

The development and implementation of social prescribing should also be responsive to the needs and view of professionals involved in social prescribing. For social prescribing to work effectively referral processes and feedback mechanisms should be embedded in existing systems of working such as case management and broader service pathways and transition processes.

4. Multi-stakeholder and inter-disciplinary collaboration throughout the development and implementation of social prescribing

Principles 1-3 highlight the multi-stakeholder and inter-disciplinary nature of social prescribing. Ongoing and effective collaboration between stakeholders and disciplines, based on mutual trust and understanding, is an essential component in the effective development and implementation of social prescribing.

5. Understanding the delivery of social prescribing as a process of adaptive implementation

As a relatively new phenomenon social prescribing services should be developed and implemented adaptively on a ‘test and learn’ basis. This requires commissioners to accept refinements to what and how a service delivers based on lessons learned during its implementation rather than focus on predefined performance targets. It also requires organisations involved in the delivery of social prescribing, and wider stakeholders, to feel confident that they can have a dialogue with commissioners about what needs to change without adversely affecting how ‘performance’ is viewed.

Although these principles have been framed in the context of the development and implementation of social prescribing they ought to have broader applicability to other areas of public service delivery that require the involvement of or engagement with a broad range of upstream and downstream stakeholder perspectives. One area in which they ought to resonate particularly strongly is service areas embarking on processes of transformation, for it is here that the need to provide innovative policy solutions and collaborate with key stakeholders is most clearly evident.

Conclusion

Through this policy commentary I have documented the emergence of social prescribing policy and introduced the idea of social prescribing ‘plus’ as an example of how the policy could evolve in the future. In doing so I have reframed social prescribing in the context of a broader body of literature on asset-based and collaborative approaches to designing and implementing innovative ways to support people with multiple and complex needs through integrated health and social care services. Although the ideas and arguments I have proposed require further empirical and theoretical elaboration they will hopefully provide a start point for critical reflection and debate about if and why social prescribing and associated approaches should become a permanent and central feature of health and social care services across the UK. They ought also to feed into to wider debates about how public sector bodies involve voluntary and community organisations, and the people they represent, in the transformation and commissioning of public services.

Returning to my original question of whether social prescribing represents a more substantive step-change in the way policymakers think about the design and delivery of health and social care policy, the unsatisfactory answer has to be that the jury is still out. The evidence suggest cautious optimism is merited: through social prescribing ‘plus’ in particular policymakers in a number of localities have embraced the principles of asset-based working and collaborative innovation but whether this amounts to a genuine step-change in their approach will need to be assessed over the longer term. The current interest in social prescribing cannot be decoupled from the policy and politics of public sector austerity and transformation and a number of commentators have argued that asset-based approaches could become a smokescreen for reductions in statutory provision of public health, care and welfare services, alongside further marketisation of public services, and the withdrawal of the social rights of citizens (Friedli, 2013). These critics suggest that only when asset-based approaches like social prescribing are adopted and invested in as a mechanism for reducing barriers to the resources necessary for good health, and framed as a core strategy for increasing equity in health (South et al, 2013), should they be embraced as an opportunity to increase the involvement of individuals, communities and organisations that represent and support them, in public services.

In this vein, it seems the true testing ground for social prescribing will be how local policymakers develop policy and commission services moving forward: will their approaches draw on the asset-based collaborative principles that are evident in the development and implementation of social prescribing ‘plus’; or will social prescribing become a convenient way of framing an expectation that people and communities need to do more to help themselves, without significant investment in the capacity and capabilities necessary to support this alternate model of welfare. In practice, this will require a shift in the debate about social prescribing at local and national level, from asking “how can we do social prescribing” to “what does it mean to do it“? I suggest that only if this happens, and asset-based collaboration is embraced, will the potential of social prescribing ‘plus’ to embody a step-change in health social care policy be realised.

1 The author has been involved formally in evaluations of four local social prescribing programmes and participated in numerous policy fora aimed at developing local approaches to social prescribing across the UK.

Chris Dayson, CRESR, Sheffield Hallam University, Unit 10, Science Park, Howard Street, Sheffield, S1 1WB. Email: c.dayson@shu.ac.uk

Ansell, C. Sorensen, E. and Torfing, J. (2017) Improving policy implementation through collaborative policymaking. Policy and Politics, 45, 3, 467-486. CrossRef link

Brooks, F. and Kendall, S. (2013) Making sense of assets: what can an assets based approach offer public health? Critical Public Health, 23, 2, 127-130. CrossRef link

Dayson, C, (2017) Evaluating social innovations and their contribution to social value: the benefits of a ‘blended value’ approach. Policy and Politics, 45, 3, 395-411. CrossRef link

Department of Health (2014) Wellbeing and why it matters to health policy. London: Department of Health.

Durie, R. and Wyatt, K. (2013) Connecting communities and complexity: a case study in creating the conditions for transformational change. Critical Public Health 23, 2, 174-187. CrossRef link

Friedli, L. (2013) What we’ve tried, hasn’t worked: the politics of assets based public health. Critical Public Health, 23, 2, 131–145. CrossRef link

Hartley, J., Sorensen, E. and Torfing, J. (2013) Collaborative innovation: a viable alternative to market competition and organizational entrepreneurship. Public Administration Review, 73, 6, 821-30. CrossRef link

Hopkins, T. and Rippon, S. (2015) Head, hands and heart: asset-based approaches in health care: a review of the conceptual evidence and case studies of asset-based approaches in health, care and wellbeing. London: Health Foundation.

Hood, C. (1991) A public administration for all seasons? Public Administration, 69, 1, 1-19. CrossRef link

Hughes, G. (2017) New models of care: the policy discourse of integrated care. People, Policy and Place, 11, 2, 72-89.

Kimberlee, R. (2015) What is social prescribing? Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 2, 1, 102-110. CrossRef link

McLean, J. (2011) Asset Based Approaches to Health Improvement: Redressing the Balance. Briefing Paper 9. Glasgow: Glasgow Centre for Population Health.

Morgan, A. and Ziglio, E. (2007) Revitalising the evidence base for public health: an assets model. Promotion & Education 2007, Suppl 2, 17-22. CrossRef link

Morgan, A. (2014) Revisiting the asset model: a clarification of ideas and terms. Global Health Promotion 21, 2, 3-6. CrossRef link

Mulgan, G. with Tucker, S. Ali, R. and Sanders, B. (2007) Social innovation: what it is, why it matters and how it can be accelerated. Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship Working Paper. Oxford: Said Business School.

NHS (2014) Improving general practice: a call to action (Phase one report). London: NHS England.

NHS North West (2010) Living well across communities: prioritising well-being to reduce inequalities. Manchester: NHS North West.

Osborne, D. and Gaebler, T. (1992) Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley

Osborne, S (2006) The New Public Governance? Public Management Review, 8, 3, 377-388. CrossRef link

Osborne, S (ed.) (2010) The New Public Governance? London: Routledge.

Sorensen, E. and Torfing, J. (2015) Enhancing public innovation through collaboration, leadership and New Public Governance, In: Nicholls, A., Simon, J. and Gabriel, M. (eds) New Frontiers in Social Innovation Research. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. CrossRef link

South, J., Higgins, T., Woodall, J. and White, S. (2008) Can social prescribing provide the missing link? Primary Health Care Research and Development, 9, 4, 310-318. CrossRef link

South J., White J. and Gamsu, M. (2013) People-Centred Public Health. Bristol: Policy Press.

Warr, D., Mann, R. and Kelaher, M. (2013) A Lot of the Things We Do… People Wouldn’t Recognise as Health Promotion: Addressing Health Inequalities in Setting of Neighbourhood Advantage. Critical Public Health, 23, 1, 95-109. CrossRef link

World Health Organisation (2012a) Health 2020: The European policy for health and well-being. Copenhagen: WHO.

World Health Organisation (2012b) Report on social determinants of health and the health divide in the WHO region. Copenhagen: WHO.