Abstract

New models of care are being pursued throughout England to balance increasing demand for improved health and social care services against reducing public expenditure. A dominant discourse has emerged about the value of community-based integrated care, despite failures of integrated care programmes to consistently demonstrate reductions in hospital admissions. Discourse analysis of integrated care policy establishes how issues of aging, hospital admissions and fragmentation are problematised, and how solutions of integrated care are made possible by the argumentative structures of the policy. These findings are discussed in relation to historical and political accounts of English health policy to identify the discursive conditions that contribute to making this discourse possible. It is argued that the policy of integrated care works as a discourse to manage tensions associated with health and social care funding, rather than as an intervention that can achieve a reduction in hospital admissions.

Interpretative policy analysis, discourse analysis, integrated health and social care, emergency hospital admissions, chronic health conditions, older people

Integrated care is a long-standing policy response by successive UK governments to concerns about the cost and complexity of the NHS and social services. The policy to integrate health and social care is intended to address inter-related financial, organisational and patient-centred concerns. Policies of integration and joining-up of services, budgets and government departments are neither limited to health policy, nor are new. A case study of the successful integration of health and social care for older people in Torbay (Thistlethwaite, 2011) refers to the Central Policy Review Staff’s Joint Framework for Social Policies produced in 1975 to demonstrate the longevity of an approach that endorses inter-agency working. Similarly to efforts to integrate care, the Joint Framework seeks to constrain expenditure on social programmes and improve co-ordination between services, as well as conducting better analysis of complex problems (HMSO, 1975). Concerns relating to the high proportion of public sector resources people with complex needs consume as they receive a multiplicity of interventions from different organisations are shared beyond health policy, for example by the Troubled Families Programme which targets families experiencing multiple disadvantage (Bond-Taylor, 2017).

Within health policy, the concern to co-ordinate responses to people who use multiple services is incorporated in policies to integrate health and social care. Integrated care is presented as being person-centred and responsive, and therefore better for individuals. It is also regarded as being better for the health system because of its cost-effectiveness. The policy is taken up in NHS strategy as a vision of ‘new models of care’ (NHS England, 2014). New models of care, requiring organisational changes to break down existing barriers between services, are expected to provide more person-centred, proactive and cost-effective care, and to reduce emergency hospital admissions. Older people, being likely to use multiple services across health and social care, and to require hospital admissions, are a major focus of these policies.

Integrated care for older people

Evaluations of English integrated care programmes to improve the co-ordination of health and social care for older people, and to reduce hospital admissions, have shown limited success. The Partnerships for Older People Projects (POPPs) 2006-09 had an effect on emergency bed days (Windle et al., 2009) and the Integrated Care Pioneers launched in 2013 claim some success in reducing the growth of emergency admissions (NHS England, 2017). However, evaluations of the Evercare pilots of case management for older people 2003-05 (Gravelle et al., 2007) and the Integrated Care Pilots 2009-11 (Roland et al., 2012) failed to show the desired impact on emergency admissions, although other benefits of the programmes were identified. A Nuffield Trust review of community-based interventions concluded that out of more than 30 evaluations, only one intervention had reduced emergency hospital admissions and therefore costs to the NHS (Bardsley et al., 2013).

The research evidence reinforces this mixed view of the success of integrated care interventions in reducing hospital admissions. Johri et al’s systematic review of integrated care experiments found integrated care could have beneficial effects on rates of institutionalisation and costs (Johri et al., 2003). However, Ouwens et al’s review of systematic reviews found that although integrated care can lead to improved quality of care, effects on hospitalisation were only significant in three of the 13 reviews included in their study (Ouwens et al., 2005). Purdy et al’s series of systematic reviews of interventions to reduce hospital admissions found some evidence of effectiveness of certain interventions for specific groups of patients, but insufficient evidence that many other schemes reduced unplanned admissions (Purdy et al., 2012). Furthermore, a systematic review of case management, the most common component of integrated health and social care in the UK according to Stokes et al (Stokes et al., 2016), found it did not have an impact on hospital admissions (Huntley et al., 2013). This lack of evidence that integrated care can consistently reduce emergency admissions causes Damery et al, following their umbrella review of systematic reviews, to query the feasibility of integrated care delivering the expected reduction in emergency hospital admissions prescribed in national targets (Damery et al., 2016).

The lack of evidence of effectiveness of integrated care programmes in reducing hospital admissions, and the evidence that shows it is not effective, is not reflected in the dominant policy discourse which consistently and repeatedly frames integrated care as a solution to a range of different problems. Analysis of this policy therefore requires a re-framing of integrated care, not just as an intervention to be evaluated, but as a discourse that requires interpretation. In this paper I ask the research questions: how is this discourse constructed, what conditions make this discourse possible, and what are the consequences? I start by introducing the methodology of interpretative policy analysis.

Methodology: policy as discourse

I use an interpretative approach in this paper to re-frame integrated care as a policy discourse, rather than as an intervention. Interpretative policy analysis asks questions about the underlying arguments, choices and context of policy. The focus is more on understanding the values and beliefs that are expressed through the policy than evaluating effectiveness. An interpretivist epistemological understanding of policy underpins this approach which assumes that a policy is about more than that which is immediately apparent in the text; the policy of integrated care does not simply set out a rational solution to a technical problem. Rather, the policy contains an ‘architecture of meaning’ reflecting wider social issues that can be shown through systematic investigation of aspects of the policy (Yanow, 2000). Analysing policy as discourse draws attention to the argumentative structures that constitute the discourse (Hajer, 2006) including the way in which problems in policy are constituted. To follow Bacchi’s approach to policy as discourse (Bacchi, 2000) is to reject the idea that problems are simply naturally occurring, needing to be solved, but instead that they are constituted in the discourse. This is not to suggest that these problems don’t exist, but that the way in which they are framed requires examination, not least because the framing of problems generates certain solutions, and negates others.

This approach assumes that policy, as discourse, is not produced in isolation, but is related to the social context within which is it produced. Policy also contributes to that context by reproducing power relations through discursive structures. The policy of integrated care as a solution to a range of related problems has persisted throughout different administrations in the UK, suggesting that it is influenced, and made possible, by a wider range of social factors than party politics. Interpretative policy analysis therefore involves analysing the social and political context of the policy (Shaw and Greenhalgh, 2008).

The benefit of this methodological approach is to provide a way of considering policy not just as a solution to a set of problems, but as a reflection of the circumstances which produce it, and, potentially to provide an explanation as to why a policy is pursued despite a lack of consistent evidence of its effectiveness. Analysing policy as discourse can provide insights to the connections between different policies, for example health and economic policy, and therefore a way of studying wider systems of meaning than which otherwise might be apparent. It is therefore an appropriate approach to respond to the research questions posed above. The limitations of this approach are similar to those that apply to interpretative analysis more broadly, in that it produces an interpretation comprising results from systematic analysis of policy, rather than a single claim of truth. Furthermore, this approach will not provide definitive answers about whether the policy works or not, but instead will shed light on questions such as who it works for. The method of analysis, which is described in more detail below, is limited to policy texts and has not encompassed an analysis of the ‘community of meaning’ of policies in practice.

Discourse analysis methods

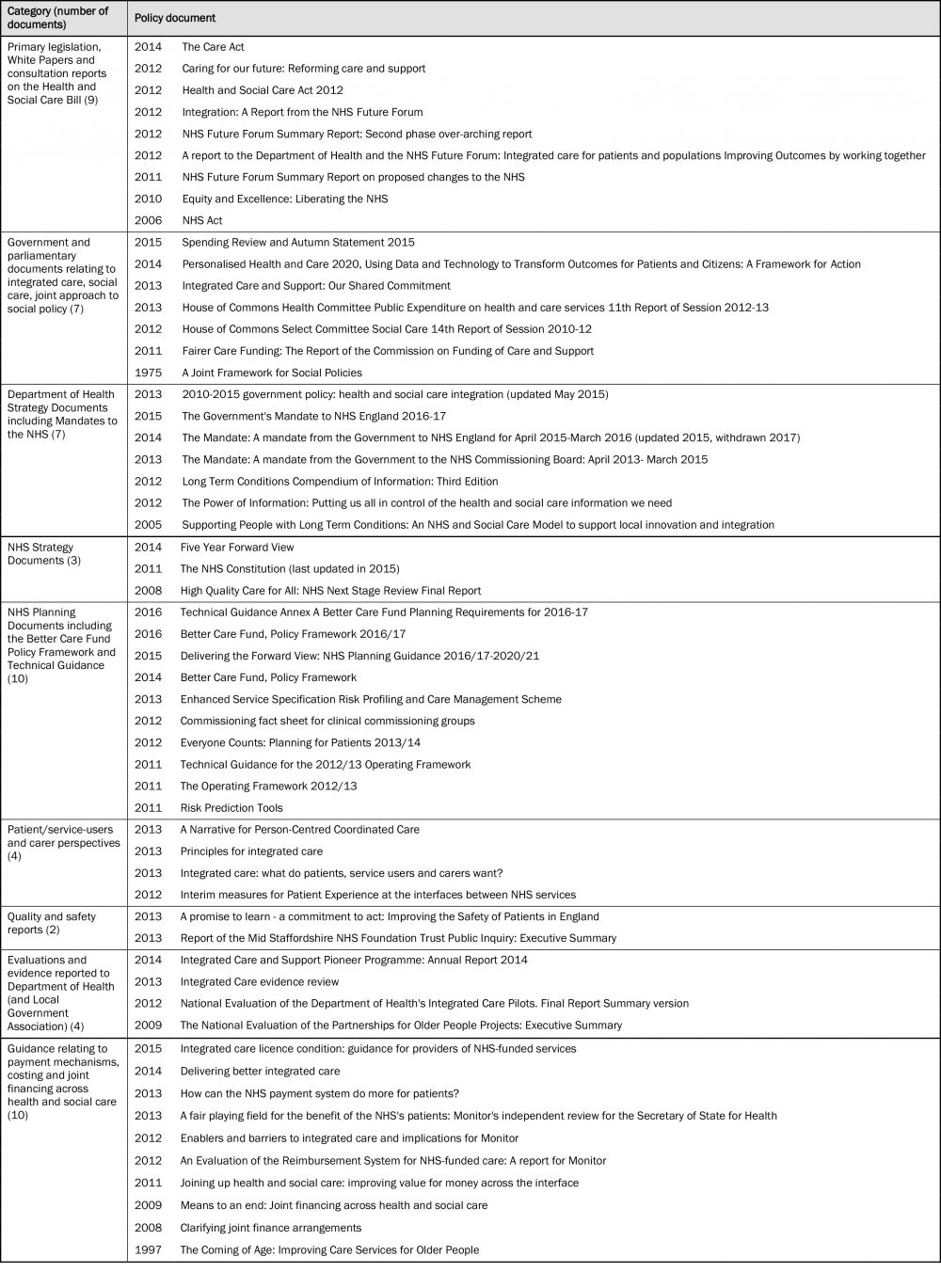

This article presents the findings of a discourse analysis of English policy on integrated care. The analysis was initiated by reading widely about integrated care in the UK, referring to official policy documents, Government legislation, debates, and grey literature including commentary on integrated care, guidance on ‘how to do’ integrated care and evaluations. I identified an over-arching discourse of integrated care from this initial reading, and developed inclusion criteria for documents to be analysed. I analysed 56 documents, selected for their direct relevance to the policy and implementation of integrated care. Documents produced by or for the UK government, or for the arms-length Government bodies charged with supporting the implementation of integrated care in England were included (integration programmes in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales have followed different paths, and are outside of the scope of this paper). Selection of documents was also informed by the wider reading initially undertaken, through a ‘snowballing’ process, with particularly close attention paid to the 2013 government policy statement (HM Government, 2013) and the collaborative statement on integrated care (Department of Health, 2013). Most of the documents (47 of 56) were produced since 2011, reflecting the most recent iterations of policy on integrated care, however earlier legislation and policies with direct relevant to the integrated care discourse were also included.

Documents (listed in Table 1 below) were categorised into nine groups: legislative papers, including Acts of Parliament, White Papers and consultation reports on the Health and Social Care Bill (later the Health and Social Care Act 2012); Government and Parliamentary documents; Department of Health policy and strategy documents; NHS strategy documents; NHS planning documents including those relating to the Better Care Fund; documents focusing on the patient perspective of integrated care; reports concerned with quality and safety; evaluations and evidence reviews relating to Department of Health initiatives; and guidance documents relating to NHS and social care payment systems and joint financing.

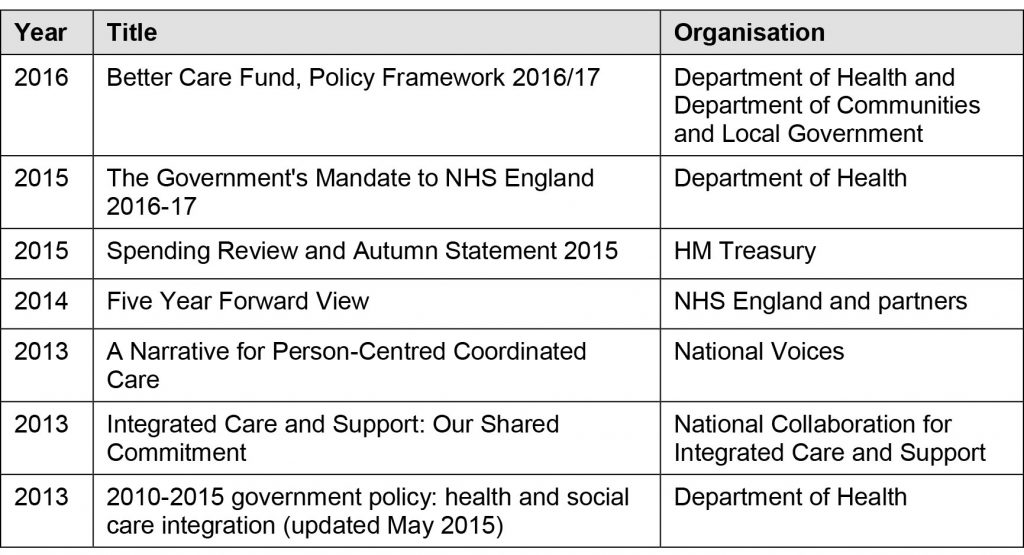

A series of questions were asked about these texts, informed by those used by Greenhalgh et al adapted from Blommaert about the historical context of the document, its purpose, authorship, rhetorical arguments and literary devices (Greenhalgh et al., 2010). This process confirmed the consistent and repeated nature of the policy discourse that had been identified from the wider initial reading. A sample of these documents was selected for detailed thematic (concerned with the policy content) and structural (concerned with the narrative and argumentative form) analysis. The sample (listed in Table 2 below) was selected as being central to current government policy on integrated care, and representing the cumulation of earlier policies. Analysis of the argumentative structures of these documents identified the ways in which the problems the policies were aiming to address were described, the causes of these problems, the solutions and the way in which the future was envisaged following the implementation of these solutions.

Findings from the policy review are provided below, before being discussed in relation to historical and political accounts of health policy.

The discourse of integrated care

A consistent and repeated use of similar concepts and argumentative structures relating to integrated care was found in the selected documents. Integrated care is repeatedly presented as a solution to the combined problems of restricted resources and increasing needs. The weight of expectation for integrated care is apparent in this introduction to a Health Select Committee’s report on expenditure:

‘Only through a new commitment to integration of the different strands of health and social care can the economic requirements of the Nicholson Challenge and the broader objectives of enhancing the quality of health and care services can be met.’ (The Committee Office, 2013)

Integrated care is described here not as a way to both save money and to improve the quality of services, but the only way to achieve this dual goal (the Nicholson Challenge refers to the then CEO of the NHS making a commitment to save £20 billion by 2014/15).

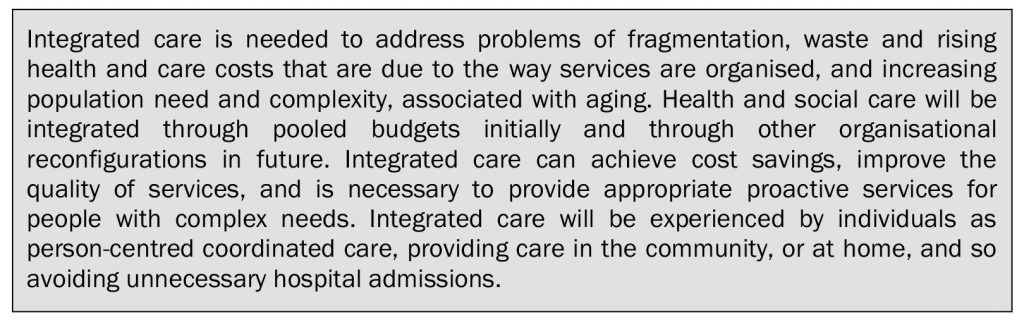

A consistency in the description of the problems that services face, the causes of those problems, and the ways in which integrated care can resolve these was found across the broader policy review which was confirmed by detailed analysis of the content and structure of the smaller sample. A synthesis of the common components and the argumentative structures in this sample is provided as a way of summarising the discourse (Box 1).

A single solution of integrated care promises to simultaneously address a combination of problems: rising costs, services that are not well organised, unnecessary hospital admissions, and increasing numbers of elderly people. An examination of the problematisation of demand for, and supply of, health services follows.

Problematisation of an aging population, hospital admissions and fragmented services

Integrated care policy represents problems in particular ways. Examining problematisation involves unpacking the implicit assumptions that render these issues problems, and therefore in need of solutions. This is not to deny that problems exist, rather it enables a clearer understanding of how problems are constructed in argumentative form, by whom and when.

Integrated health and social care is seen as particularly important for people with multiple chronic conditions, including older people, but is also seen as relevant for children with complex needs, people with mental health and physical health needs or anyone who needs to access a range of different services, indeed the policy aspiration is that integrated care is available to all (Department of Health, 2013). However, the problems associated with an aging population are those that feature most consistently in policy as presenting increasing costs, and complexity of need. The aging population is repeatedly presented as a new challenge to be faced, a growing burden for the twenty-first century as an outcome of increasing longevity. The needs of the aging population are included in the case for change presented in the NHS Five Year Forward View and by the Department of Health:

[The NHS] needs to evolve to meet new challenges: we live longer, with complex health issues, sometimes of our own making.

Over the past five years -despite global recession and austerity -the NHS has generally been successful in responding to a growing population, an ageing population, and a sicker population, as well as new drugs and treatments and cuts in local councils’ social care. (NHS England, 2014)

The number of people in England who have health problems requiring both health and social care is increasing. For example, in the next 20 years, the percentage of people over 85 will double. This means there are likely to be more people with ‘complex health needs’ – more than one health problem – who require a combination of health and social care services. (HM Government, 2013)

Presenting the aging population as a new challenge for the NHS provides a rationale for changing organisational structures, as existing models of care are portrayed as antiquated, not fit for purpose. The use of hospital services by older people has also been of continued concern to health policy, as explored further below.

Reducing emergency, or non-elective, hospital admissions is a specific target of government policy (HM Government, 2016) The problematisation of hospital admissions evokes the high costs of hospital care and therefore the waste associated with avoidable admissions, as well as iatrogenic effects of admission, and individuals’ preferences to be cared for at home rather than to be admitted to hospital. Emergency admissions are regarded as an indicator of poor system performance, with variability being assessed to determine factors that could improve performance (Wilson et al., 2015). An example of the extent to which emergency hospital admissions are problematised is found in a foreword by the then Ministers for Health and Social Care to a policy document in 2013:

We must provide a seamless service focussed on the individual within their own home. A big part of this will be working to ensure that we avoid crises in people’s care which too often result in hospital admissions. This should always be regarded as a failure. If we can do better at preventing deterioration of health then we know that fewer people will end up in hospital. Instead they will receive the right care, when and where they need it. (My emphasis) – Jeremy Hunt and Norman Lamb, Foreword (Department of Health, 2013)

Hospital admissions are presented in this extract as a failure, with the preference for community or home-based care implying that hospital care is the wrong care provided in the wrong place at the wrong time. Amongst other factors, unnecessary hospital care is attributed to a lack of a ‘seamless’ service.

Fragmentation of care

The antithesis of a seamless service is one that is fragmented, which is how health and social care is portrayed. Fragmentation indicates a lack of coordination, leading to wasteful duplication, for example in assessment processes. It implies there are gaps between services through which people can fall, preventing them from accessing the care they need, resulting in worsening conditions and hospital admissions.

…services often don’t work together very well. For example, people are sent to hospital, or they stay in hospital too long, when it would have been better for them to get care at home. Sometimes people get the same service twice – from the NHS and social care organisations – or an important part of their care is missing. (HM Government, 2013)

The problematisation of fragmentation, whether within health services or between health and social care, leads to a solution of integration and co-ordination. A co-ordinating function is integral to case management, which is seen as being able to reduce hospital admissions by providing preventative care. Preventative care therefore becomes aligned with integrated care, as described in the vision of the future found in the Five Year Forward View:

It is a future that dissolves the classic divide, set almost in stone since 1948, between family doctors and hospitals, between physical and mental health, between health and social care, between prevention and treatment. One that no longer sees expertise locked into often out-dated buildings, with services fragmented, patients having to visit multiple professionals for multiple appointments, endlessly repeating their details because they use separate paper records. One organised to support people with multiple health conditions, not just single diseases. (NHS England, 2014)

The problematisation of the aging population, fragmentation of services and hospital admissions is constructed through the choice of language and argumentative structures in the policy of integrated care, contributing towards the acceptability of integrated care as a solution.

The solution of integrated care models

A better way of managing care for people with long term conditions, and reducing emergency hospital admissions was offered by the Department of Health in 2005 (Department of Health, 2005). Instead of ‘reactive, unplanned and episodic’ care that leads to ‘heavy use’ of hospital services, alternative models of integrated care were proposed based on those used by Evercare and Kaiser Permanente (both US managed care organisations), drawing on the Chronic Care Model. This model has been influential internationally (Nolte and McKee, 2008) and informed the development of the WHO European health systems perspective on integrated care (Grone and Garcia-Barbero, 2001). Since 2005 UK health policy has promoted a version of the Chronic Care Model, as part of the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention programme which aims to improve quality of care whilst managing financial pressures (Department of Health, 2012a).

The influence of American health policy on the UK includes the introduction of ideas in the 1980s that contributed to the development of the internal market (Klein, 2010). However, it appears to have been a direct comparison between Kaiser Permanente and the NHS that led to the importing of the American approach to case management. Feachem et al concluded that the American organisation was more efficient than the NHS because of: integration (particularly disease management of chronic care), lower use of hospital beds, the benefits of competition, and efficient information technology (Feachem et al., 2002). Beliefs about the cost-effectiveness of the NHS were challenged by this comparison which sparked considerable debate about the method of comparison and the validity of the conclusions. Regardless of the fundamental flaws in the methodology set out by Talbot-Smith et al in their refutation of Feachem et al’s conclusions (Talbot-Smith et al., 2004), the possibility that integrated care, and case management, could contain costs by reducing hospital use was taken up by UK health policy. Another American model, Evercare, had also demonstrated a reduction in hospitalisations and costs (Kane et al., 2003). Exchanges of information with the US culminated in United Healthcare running pilots of Evercare in the UK (Boaden et al., 2005), although, as noted above, these failed to demonstrate expected reductions in hospital admissions (Gravelle et al., 2007).

Integration of funding

Integration of funding is a component of the US models. Current English policy seeks to integrate aspects of health and social care funding in the Better Care Fund, with a view to achieving full integration by 2020 (HM Government, 2016). The Better Care Fund is a joint health and social care fund, seen as the starting point from which health systems will graduate to a range of new organisational configurations, such as Accountable Care Organisations, lead commissioning models or devolution. Accountable Care Organisations, based on US organisational models similar to Kaiser Permanente as noted above, take responsibility for providing health care for a defined population, within a set budget. This approach integrates not just different budgets but also brings together purchasers and providers into a single organisational model. The organisational limit on the funding available for services to be provided to the assigned population encourages preventative and proactive care to keep costs down.

Organisational integration risks conflicting with other aspects of English health policy that promote competition and choice, as noted by the NHS Future Forum in relation to the NHS Health and Social Care Bill (Department of Health, 2012b). To respond to these concerns, the 2012 Health and Social Care Act charged Monitor, the then regulator of health services, with the duty of enabling integrated care, expressed in guidance that requires health providers to ‘not act in a way that would be detrimental to enabling integrated care’ (Monitor, 2015). The tension between integration and competition is thus managed.

In summary, the findings of the discourse analysis of integrated care policy were that aging, hospital admissions and fragmentation of services were problematised in the policy discourse, contributing towards creating the discursive conditions for the solutions of integrated care models from the US to be pursued.

Discussion

Having examined the argumentative structures of integrated care policy, I now turn to explore some of the wider discursive conditions that have historically contributed towards creating an environment that makes the current discourse of integrated care possible, and discuss some of the effects of the discourse. The discourse of integrated care is not new. Questions of how to reduce reliance on institutional care, and how to fund and afford the NHS have been discussed continually since at least 1948 and the founding of the Welfare State. Integrated care is one of the answers to these, and other, questions. I argue that the discourse of integrated care helps to manages the inherent tensions of providing universal health care, and means-tested social care, within decreasing funds available for public expenditure.

Ongoing problematisations

Historical and political accounts of the development of health policy, the Welfare State and the NHS (Timmins, 1995; Klein, 2010; Ham, 2009; Webster, 2002; Glasby, 2012) show that concerns about the aging population, admissions to hospitals, and how to best manage and organise services have occurred throughout the history of the NHS, and are closely related to concerns about spiralling costs and the seemingly continual growth in demand. Concerns about the increasing costs of an aging population, associated with the success of the NHS in increasing life expectancy, have been repeatedly voiced, for example by the Conservative Minister for Health, Walker-Smith, in 1958:

…by increasing the expectation of life, we put greater emphasis on the malignant and degenerative diseases which are characteristic of the later years.

And by Richard Crossman, Secretary of State for Social Services in 1969:

…the pressure of demography, the pressure of technology, the pressure of democratic equalisation, will always together be sufficient to make the standard of social services regarded as essential to a civilised community far more expensive that that community can afford. (Klein, 2010)

Concerns about hospitalisation of older people are traced to the 1950s by Glasby and Littlechild, in their explanation of the health and social care ‘divide’ for older people (Glasby and Littlechild, 2004). Similar concerns are raised by the Audit Commission in their scrutiny of the appropriateness of hospital admissions for older people in the 1990s (Audit Commission, 1997). During both these periods the availability of resources (residential or intermediate care, and funding for costly hospital care), prompted concerns about hospital admissions. Further, the complex needs of older people were categorised as falling somewhere between health and social care, not acutely ill enough for hospital care, yet unable to manage at home. This division between health and social care is at the heart of much of the so-called fragmentation that integrated care attempts to address, and that leads to the inequities highlighted by the Royal Commission on Long Term Care in 1999 (Glasby, 2003) and again more recently by the Dilnot Commission (Dilnot, 2011) and the Barker Commission (Barker, 2014) whereby needs arising from illness will be met by health funding, but needs relating to social care will not. This divide stems from the NHS Act and the National Assistance Act in 1948; universal health care, free at point of access is provided by the first piece of legislation and social care by the second, through means-testing. Hospital care is therefore provided by the NHS, but residential and domiciliary care is not, making the provision of care for people with both health and social care needs a contested area, played out particularly in the arena of reducing hospital admissions. Integrated care, through pooling health and social care budgets, provides a discursive way of managing these tensions, and through the possibility of reducing overall costs, a way of managing further tensions about the affordability of the NHS.

Continual concerns about costs

Concerns about the cost of the NHS and the difficulties in containing these costs first surfaced only a few months after it was founded. The assumption in the Beveridge Report that health costs would decline as the people become healthier was soon proven wrong (Ham, 2009). Instead, explanations as to why costs were greater than expected were already being made by Bevan, Minister for Health, to the rest of the Cabinet in December 1948 (Klein, 2010). Webster, in his political history of the NHS, asserts that the level of funding made available to the NHS is determined by the state of the economy rather than objective merit (Webster, 2002). The NHS therefore becomes an instrument for rationing resources rather than meeting needs (Klein, 2010, Joyce, 2001). How much money to allocated to the NHS is a political choice, influenced by wider economic circumstances and policies than purely the healthcare needs of the population. Although there have been many myriad factors affecting the level of funding provided to the NHS since its inception, current levels of funding are shaped by the UK government’s policy of austerity, whereby since 2009 public expenditure has been reduced as part of economic policy to strengthen the economy. The Spending Review (HM Treasury, 2015) makes a clear statement that health and social care expenditure drains rather than strengthens the economy, and is only therefore affordable when the economy is strong. Public expenditure is sacrificed to achieve the aim of economic growth, under the slogan of austerity. Economic growth consistently remains the over-riding goal of the UK government with discussions about levels of public spending concerned with whether it will promote or inhibit economic growth (Reeves et al., 2013). This economic discourse is moderated by the persistent public popularity of the NHS, and the political imperative to continue to support this well-loved public institution. The tension between the political desire to contain spending whilst retaining the institution creates a discursive environment that continually seeks efficiencies, value for money, cost containment and returns on investment.

Questions are therefore repeatedly raised about how best to pay for the cost of the NHS, and how to control expenditure. No review has concluded with any better system of financing the NHS than through taxation (Timmins, 1995; Ham, 2009). Within the economic discourse constraining public expenditure, health policy has therefore focused on ways of controlling expenditure and growth. Major restructuring of the NHS in the 1970s sought to achieve more objective allocations of funding and tighter expenditure controls in a national planning system with cash limits (Webster, 2002, Ham, 2009). Competition for resources was introduced by the internal market in the 1990s, when the purchasing of healthcare was split in organisational terms from the provision of healthcare. The mechanisms of purchasing, including commissioning, procurement and contracting, remain as the processes that are expected to lead to integration, whether via the pooling of health and social care budgets, or through personal health budgets and direct payments.

There have been attempts to manage demand for health care as well as supply-side changes. The Wanless report’s ‘fully engaged’ scenario of dramatic improvements in public health predicted a reduction in the need for health care (Wanless, 2002). The current policy of integrated care, or new models of care, offers a way of combining supply-side improvements with reductions in demand for hospital admissions. Integrated care can also smooth over tensions between universal healthcare and means-tested funding by pooling budgets, as well as potentially bringing together providers and commissioners. The link made between these organisational and financial approaches to integration and the benefits for patients make this a ‘compelling narrative’ (Ham and Smith, 2010).

In summary, the architecture of meaning found in integrated care policy is one that serves to maintain and manage current divisions between health and social care. Integrated care works as a policy, not in terms of reducing hospital admissions, but in terms of managing tensions. Repeated policy recommendations for integration, joint commissioning, pooled budgets, and new models of care, serve to manage tensions between the desire to restrict growth in public expenditure whilst maintaining the popular NHS, and to manage tensions between the different funding regimes of health and social care.

Concluding comments

Discourse analysis has: illuminated the underlying arguments and systems of meaning of integrated care; identified some of the conditions that have contributed to the discourse; shown how it ‘works’, not as an intervention that can reduce hospital admissions, but as a way of managing a range of policy tensions. I have located this discourse within the historical and political policy context, showing that there has been a degree of continuity of problematisations of the aging population, hospital admissions and fragmentation of services. I have identified discursive conditions about the funding of the NHS that have permitted this discourse to unfold. The paper locates current health policy, which is concerned with organisational changes that will reduce demand for health services, in a wider discourse about economic growth and public expenditure, and found that the concerns that new models of care attempt to address are not new. The consequences of this discourse are that tensions are managed, and smoothed over. In this way, divisions between health and social care are able to continue, as are policies of austerity that restrict health and social care funding.

Finally, this analysis connects health policy with wider economic policy, which means that the effects of the discourse are not just important for health and social care but also have wider implications for the economy, given that there is evidence (Reeves et al., 2013) that austerity politics are not only damaging for population health but also for the economy.

Gemma Hughes, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom. Email: gemma.hughes@gtc.ox.ac.uk

Audit Commission (1997) The Coming of Age: Improving care services for older people. London: Audit Commission. Available at: http://archive.audit-commission.gov.uk/auditcommission/SiteCollectionDocuments/AuditCommissionReports/NationalStudies/TheComingofAge.pdf [Accessed: 12/05/2014]

Bacchi, C. (2000) Policy as Discourse: What does it mean? Where does it get us? Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 21, 1, 45-57. CrossRef link

Bardsley, M., Steventon, A., Smith, J. and Dixon, J. (2013) Evaluating integrated and community-based care – evaluation summary. London: Nuffield Trust.

Barker, K. (2014) A new settlement for health and social care: Final report. London: The King’s Fund.

Boaden, R., Dusheiko, M., Gravelle, H., Parker, S., Pickard, S. and Roland, M. (2005) Evercare evaluation interim report: implications for supporting people with long-term conditions Manchester: National Primary Care Research and Development Centre. Available at: http://www.population-health.manchester.ac.uk/

primarycare/npcrdc-archive/Publications/evercare%20report1.pdf [Accessed: 11/02/2014]

Bond-Taylor, S. (2017) Domestic Surveillance and the Troubled Families Programme: Understanding relationality and constraint in the homes of multiply disadvantaged families. People, Place and Policy, 10, 3, 207-224.

Damery, S., Flanagan, S. and Combes, G. (2016) Does integrated care reduce hospital activity for patients with chronic diseases? An umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open, 6, 11. CrossRef link

Department of Health (2005) Supporting People with Long Term Conditions. London: Department of Health.

Department of Health (2012a) Long Term Conditions Compendium of Information: Third Edition. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/

system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216528/dh_134486.pdf [Accessed: 21/10/13]

Department of Health (2012b) Integration: A Report from the NHS Future Forum. London: Department of Health. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government

/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216425/dh_132023.pdf [Accessed: 8/12/2013]

Department of Health (2013) Integrated Care and Support – Our Shared Commitment National Collaboration for Integrated Care and Support. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/198748/DEFINITIVE_FINAL_VERSION_Integrated_Care_and_Support_-_Our_Shared_Commitment_2013-05-13.pdf [Accessed: 23/07/2013]

Dilnot, A. (2011) Fairer Care Funding: The Report of the Commission on Funding of Care and Support. London: Commission on Funding of Care and Support. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130221130239/

https://www.wp.dh.gov.uk/carecommission/files/2011/07/Fairer-Care-Funding-Report.pdf [Accessed: 31/03/2014]

Feachem, R. G. A., Sekhri, N. K. and White, K. L. (2002) Getting more for their dollar: a comparison of the NHS with California’s Kaiser Permanente. British Medical Journal, 324, 7330, 135-141. CrossRef link

Glasby, J. (2003) Bringing down the ‘Berlin Wall’: the Health and Social Care Divide. British Journal of Social Work, 33, 7, 969-975. CrossRef link

Glasby, J. and Littlechild, R. (2004) The health and social care divide: the experiences of older people. Rev. 2nd ed. edn. Bristol: Policy Press.

Glasby, J. (2012) Understanding health and social care. Understanding welfare series. 2nd edn. Bristol: Policy Press.

Gravelle, H., Dusheiko, M., Sheaff, R., Sargent, P., Boaden, R., Pickard, S., Parker, S. and Roland, M. (2007) Impact of case management (Evercare) on frail elderly patients: controlled before and after analysis of quantitative outcome data. BMJ, 334, 7583, 31. CrossRef link

Greenhalgh, T., Hinder, S., Stramer, K., Bratan, T. and Russell, J. (2010) Adoption, non-adoption, and abandonment of a personal electronic health record: case study of HealthSpace. BMJ, 341. CrossRef link

Grone, O. and Garcia-Barbero, M. (2001) Integrated care: a position paper of the WHO European Office for Integrated Health Care Services. International Journal Integrated Care, 1, e21. CrossRef link

Hajer, M. A. (2006) Doing discourse analysis: coalitions, practices, meaning, In: van den Brink, M. and Metze, T. (eds.) Words matter in policy and planning: discourse theory and method in the social sciences. Netherlands Geographical Studies. Utrecht: Netherlands Graduate School of Urban and Regional Research: 65-74.

Ham, C. (2009) Health policy in Britain. 6th ed. edn. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. CrossRef link

Ham, C. and Smith, J. (2010) Removing the policy barriers to integrated care in England. London: Nuffield Trust. Available at: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk

/files/2017-01/removing-policy-barriers-integrated-care-web-final.pdf [Accessed: 12/05/2014]

HM Government (2013) 2010 to 2015 government policy: health and social care integration.) Department of Health and The Rt Hon Norman Lamb. First published: 25 March 2013. Last updated: 8 May 2015. London: HM Government. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2010-to-2015-government-policy-health-and-social-care-integration [Accessed: 09/11/2015]

HM Government (2016) Better Care Fund, Policy Framework 2016/17. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/490559/BCF_Policy_Framework_2016-17.pdf [Accessed: 29/02/2016].

HMSO (1975) A joint framework for social policies, Staff, C.P.R. (1975). London: HMSO (print).

HM Treasury (2015) Spending Review and Autumn Statement 2015. London: HM Treasury.

Huntley, A. L., Thomas, R., Mann, M., Huws, D., Elwyn, G., Paranjothy, S. and Purdy, S. (2013) Is case management effective in reducing the risk of unplanned hospital admissions for older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Family Practice, 30, 3, 266-275. CrossRef link

Johri, M., Beland, F. and Bergman, H. (2003) International experiments in integrated care for the elderly: a synthesis of the evidence. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18, 3, 222-35. CrossRef link

Joyce, P. (2001) Governmentality and risk: setting priorities in the new NHS. Sociology of Health & Illness, 23, 5, 594-614. CrossRef link

Kane, R. L., Keckhafer, G., Flood, S., Bershadsky, B. and Siadaty, M. S. (2003) The effect of Evercare on hospital use. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51, 10, 1427-34. CrossRef link

Klein, R. (2010) The new politics of the NHS: from creation to reinvention. 6th edn. Oxford: Radcliffe.

Monitor (2015) Integrated care licence condition: guidance for providers of NHS-funded services. London: Monitor. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/

uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/418493/IC_licence_condition_mar15.pdf [Accessed: 9/11/2015]

NHS England (2017) Next Steps on the Five Year Forward View. London: NHS England. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf [Accessed: 06/04/2017]

NHS England (2014) NHS Five Year Forward View. London: NHS England. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf [Accessed: 10/11/2015]

Nolte, E. and McKee, M. (2008) Caring for people with chronic conditions: a health system perspective. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Series. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Ouwens, M., Wollersheim, H., Hermens, R., Hulscher, M. and Grol, R. (2005) Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviews. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 17, 2, 141-6. CrossRef link

Purdy, S., Paranjothy, S., Huntley, A., Thomas, R., Mann, M., Huws, D., Brindle, P. and Elwyn, G. (2012) Interventions to Reduce Unplanned Hospital Admissions: A series of systematic reviews. University of Bristol, Cardiff University, NHS Bristol. Available at: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/primaryhealthcare/docs/projects/

unplannedadmissions.pdf [Accessed: 21/08/2013]

Reeves, A., Basu, S., McKee, M., Meissner, C. and Stuckler, D. (2013) Does investment in the health sector promote or inhibit economic growth? Globalization and Health, 9, 43. CrossRef link

Roland, M., Lewis, R., Steventon, A., Abel, G., Adams, J., Bardsley, M., Brereton, L., Chitnis, X., Conklin, A., Staetsky, L., Tunkel, S. and Ling, T. (2012) Case management for at-risk elderly patients in the English integrated care pilots: observational study of staff and patient experience and secondary care utilisation. International Journal of Integrated Care, 12. CrossRef link

Shaw, S. E. and Greenhalgh, T. (2008) Best research – For what? Best health – For whom? A critical exploration of primary care research using discourse analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 66, 12, 2506-2519. CrossRef link

Stokes, J., Checkland, K. and Kristensen, S. R. (2016) Integrated care: theory to practice. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 21, 4, 282-285. CrossRef link

Talbot-Smith, A., Gnani, S., Pollock, A. M. and Gray, D. P. (2004) Questioning the claims from Kaiser. The British Journal of General Practice, 54, 503, 415-421; discussion 422.

The Committee Office, Health Committee (2013) House of Commons – Health Committee – Eleventh Report: Public expenditure on health and care services. London: House of Commons

Thistlethwaite, P. (2011) Integrating health and social care in Torbay: improving care for Mrs Smith: The King’s Fund. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/integrating-health-social-care-torbay-case-study-kings-fund-march-2011.pdf [Accessed: 20/11/2013]

Timmins, N. (1995) The five giants: a biography of the welfare state. Rev. & updated ed. edn. London: HarperCollins, 2001.

Wanless, D. (2002) Securing Our Future Health: Taking a Long-Term View. London: HM Treasury. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/

www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/consult_wanless_final.htm [Accessed: 01/04/2014]

Webster, C. (2002) The National Health Service: a political history. New edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, A., Baker, R., Bankart, J., Banerjee, J., Bhamra, R., Conroy, S., Kurtev, S., Phelps, K., Regen, E., Rogers, S. and Waring, J. (2015) Establishing and implementing best practice to reduce unplanned admissions in those aged 85 years and over through system change [Establishing System Change for Admissions of People 85+ (ESCAPE 85+)]: a mixed-methods case study approach. Southampton (UK): National Institute for Health Research.

Windle, K., Wagland, R., Forder, J., D’Amico, F., Janssen, J. and Wistow, G. (2009) National Evaluation of Partnerships for Older People Projects: Final Report: University of Kent. Available at: http://www.pssru.ac.uk/publication-details.php?id=1672 [Accessed: 31/03/2014]

Yanow, D. (2000) Conducting Interpretive Policy Analysis. Qualitative Research Methods: SAGE Publications. CrossRef link