Abstract

Within the political framework of the European Union (EU), there has been long standing recognition that the on-going exclusion of Roma represents a key challenge for human rights, justice and social inclusion agendas. By introducing a requirement for Member States to produce National Roma Integration Strategies (NRIS), the European Commission hopes that Member States will work in partnership with the EU and key stakeholders to achieve inclusion objectives in respect of housing, health, education and employment. The form and content of the United Kingdom’s (UK) NRIS submission has been criticised in a number of key areas; notably its ‘migrant blind’ approach (Craig, 2011; 2013). This article draws on recent research undertaken by the authors (Brown, Martin and Scullion, 2013), which aimed to estimate the size of the recently arrived Roma population in the UK and document some of the local level responses as a result of this migration. It provides an overview of the context giving rise to the research, and how previous population estimates have been attempted, both across the EU and in the UK. The paper considers whether conventional methodologies can be fit for purpose when attempting to assess the population size of a transnational and highly mobile ethnic group, or whether more experimental approaches might yield a fresh approach. More specifically, it examines the strengths and weaknesses of adopting a place typology approach (Lupton et al., 2011). Finally the paper looks at the publication of research about Roma populations in a highly politicised arena in the wake of ongoing national and international attention on Roma.

Introduction

The social exclusion faced by members of Roma communities living in European Union (EU) Member States has been widely acknowledged (see Amnesty International, 2011; Bartlett, Benini and Gordon, 2011; Brown, Dwyer and Scullion, 2013). Although funding and policy instruments aimed at Roma inclusion have been available for a number of years, the European Commission has argued that there has often been an implementation gap at the national, regional and local levels (Reding, 2012). The main reasons cited for the limited effectiveness of existing mechanisms are a lack of political will, a lack of strong partnerships and coordination mechanisms, but also an unwillingness to acknowledge the needs of Roma as an issue (European Commission, 2010).

In 2011, the European Commission called on all Member States to prepare, or adapt, strategic documents to meet four key EU Roma integration goals: access to education, employment, healthcare and housing (European Commission, 2011). This acknowledged that progress on Roma integration had not been satisfactory and explicitly requested that states develop comprehensive strategies (referred to as National Roma Integration Strategies or NRIS) which included ‘targeted actions and sufficient funding (national, EU and other) to deliver’ on the goals (European Commission, 2011: 4). Later in 2011, all 27 Member States agreed to a set of conclusions that endorsed the EU Framework for coordinating national Roma strategies. As detailed by the Open Society Foundations (2011: 2):

The Conclusions commit member-states to “improve the implementation and strengthen the effectiveness of EU funds”, and make better use of technical assistance. They are much bolder on inclusion of Roma in decision-making processes than the Framework and have a strong focus on Roma empowerment through participation in policy debate and implementation. EPSCO invited the Commission “to pursue rigorous monitoring of the implementation of Council Directive 2000/43/EC”, arguably the EU’s most powerful instrument for combating discrimination based on ethnic origin. EPSCO also highlighted the need to intensify the fight against trafficking of Roma and to guarantee the legal rights of Roma victims of trafficking.

The approach of the United Kingdom

Responsibility for producing the UK NRIS was assumed by the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG). In an explanatory Memorandum to the Parliamentary European Scrutiny Committee, the Minister of State outlined the UK’s position. This Memorandum stated that the EU Framework contained no new proposals for legislation and is intended to ‘complement and reinforce the EU’s equality legislation by creating a political commitment to address the specific needs of Roma in the four integration goal areas’ (cited in the European Scrutiny Committee, Department for Communities and Local Government, 2011). Furthermore, the Minister asserted that:

The Government’s priorities therefore are to ensure that the Conclusions, which will be adopted by 19th May EPSCO encourage those Member States with large, and often seriously disadvantaged Roma populations to take effective action; whilst at the same time not ceding any new powers or competence to the Commission and without accepting additional requirements above what the UK is in any case already doing, such as by ensuring sufficient flexibility around what constitutes national strategy, not imposing unhelpful targets, nor accepting burdensome reporting obligations on those, like the UK, with relatively few Roma citizens [emphasis added] (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2011).

The conclusions of the Committee restate that the apparent size of the Roma population in each Member State determines both the extent of the challenge they face and the nature of their response:

It [EU Framework] also recognises that, whilst Roma constitute Europe’s largest minority, the size of the Roma community as a percentage of the total population in each Member State varies significantly, and that the scale of the challenges which Member States face, as well as their starting points for tackling Roma exclusion, are likely to differ in magnitude (European Scrutiny Committee -Twenty-Eighth Report

Documents considered by the Committee on 11 May 2011, 7 DCLG (32664) Integration of Roma, publicly available online at the following link: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmeuleg/428-xxvi/42809.htm

Prior to this, a cross departmental Ministerial Working Group had been established with the task of reviewing the evidence on inequalities experienced by UK Gypsies and Travellers but which also attempted to include issues relating to Central and Eastern European (CEE) Roma, although they featured only minimally (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2012). Indeed, with the exception of issues around education there was no other mention relating to migrant Roma in the UK. At the same time, the European Social Fund allocated at least 20 per cent of a €74billion budget (2014 – 2020) to addressing social inclusion, thus providing significant resource implications for areas which invest in recently arrived disadvantaged populations. However, the lack of a specific and comprehensive NRIS, and particularly a lack of an official estimate by the Government of the number of Roma people who had moved to the UK, was seen by a number of local authorities and community based organisations as a major barrier to gaining high level recognition as to the impact this migration was having at a local level. A number of local authorities and organisations working in the field deemed that there was a clear policy imperative to enumerate the population of CEE Roma residing in the UK in order to overcome the deep social exclusion faced by members of those communities. As Craig (2011: ii) comments:

There is therefore a pressing political and policy agenda to be carried through in the UK, starting from programmes of data collection and monitoring which makes the Roma ‘visible’ as a significant minority in the UK context, and which addresses severe disadvantage across the welfare spectrum.

Such sentiments are shared by Open Society Foundations (2013: 1) who argue for the need to measure population sizes to ensure adequate resource allocations for the amelioration of social divisions:

The official invisibility of Roma people negatively affects public funding that could help Roma communities with healthcare, education, employment, and housing. This invisibility also undermines the potential for Roma political participation and Roma-led social change.

Counting ‘hard to count’ populations

The importance of counting populations has long been recognised, particularly in relation to assisting the planning and delivery of infrastructure and the allocation of resources (Hillygus et al., 2006). However, it is recognised for some groups such endeavours are punctuated by complexity. The UK Census, for example, is used for calculating the resources required in relation to health, social services, housing, transport, etc. However, as Finney and Simpson (2009) reflected in their review of how the ‘ethnic group question’ came into being within the UK’s decennial population census, ‘counting’ people who belong to certain ‘ethnic groups’ can be controversial. The White Paper issued to prepare for the 1981 Census stated that, reliable information about members of ethnic groups living in the UK was required:

In order to help in carrying out their responsibilities under the Race Relations Act, and in developing effective social policies, the Government and local authorities need to know how the family structure, housing, education, employment and unemployment of the ethnic minorities compare with the conditions in the population as a whole (cited in Finney and Simpson, 2009: 32).

However, this led to concerns by Black organisations, as well as organisations who informed the broader statistical community (ibid), about whether this data would be used pejoratively in an atmosphere of far right politics, racist policing and repatriation. However, the question was included in the 1981 Census and has remained a feature ever since. It is now generally considered that the measurement of ethnicity, size and composition, provides a rich source of data for furthering understandings of social differences. Indeed, other attempts to quantify those people belonging to other categories (for example forced labour migrants) argue that attempting to enumerate the issue is essential to inform policy makers and other stakeholders, as well as enabling assessment of progress and impact of specific policy (International Labour Office (ILO), 2012: 7).

For Gypsies and Travellers in the UK, the lack of data regarding the size of the population has been a feature until quite recently. While the commissioning of Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Needs Assessments (GTAAs) has gone someway to enumerate the population (see Niner and Brown, 2011), it was hoped that a more ‘comprehensive’ approach was being undertaken as a result of the subcategory of ‘Gypsy or Irish Traveller’ being included in the 2011 Census in the UK for the first time. Despite this inclusion, however, the 58,000 people who self-ascribed as Gypsy or Irish Traveller is still seen as a significant undercount. Such alleged understatement of the population is attributed to the lack of trust by potential respondents in official ‘counting’ processes coupled with low levels of literacy, awareness, and the failure of the Office for National Statistics to engage marginalised sections of the communities (Irish Traveller Movement in Britain, 2013).

It is recognised, however, that some populations are harder to count than others, and these undercounted populations are ‘disproportionately ethnic and racial minorities’ (Hillygus et al., 2006: 1). For example, the ILO (2012) focused on enumerating the issue of forced labour, while Sigona and Hughes (2012), in a study on ‘irregular’ migrants, provide a ‘tentative’ estimate as to the population size, whilst acknowledging the various attempts that have been deployed previously and the limitations of the source data. Furthermore, recent research from the Office for National Statistics (ONS, 2014) illustrated the difficulty of accurately estimating the population of migrants entering the UK over the 2001-2011 period.

Counting Roma

There are widely acknowledged complexities and sensitivities around ‘counting’ Gypsies, Travellers and Roma. Long standing exclusion, the fear of, and actual experiences of discrimination (see Clark, 1998; Clark and Greenfields, 2006) have added to this challenging undertaking. Complexity is increased where frequent mobility is an issue (Scullion and Brown, 2013) alongside data collection instruments often recording nationality rather than ethnicity.

A number of recent European studies focussing on particular Member States have attempted to estimate Roma populations using direct sampling of populations (see European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2009). In both the EU-MIDIS and the Roma Pilot survey (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014) a random route and focused enumeration sampling methodology was used. This entailed identifying areas within Member States where Roma were living in higher than average density based on urban/rural distributions (Personal correspondence with FRA team, 2013). However, in order to identify such areas, country specific solutions were adopted. In practice this meant for those countries where ethnicity was collected in the national population census this information was used. In other countries, where the Census did not allow for ethnicity, proxies such as first language were used. Consequently, the construction of sampling frames depended on the information available on the national level, taking into consideration only areas where Roma lived in such concentration that the sampling method would work reasonably well. Whenever possible, the density of Roma in the area compared to the national average was the preferred criterion.

At a European level, the difficulties surrounding the estimation of the Roma population can also be seen in relation to the National Roma Integration Strategies (NRIS) submitted by Member States, which contained estimates of the number of Roma in each respective country. For example, even countries such as the Czech Republic, with an enduring Roma population and a Census category of Roma, indicated that overall estimates tend to be the product of “expert estimates”, rather than comprehensive statistical returns (Minister for Human Rights, 2009). However, for many EU Member States it is noted that the difficulties of ‘counting’ Roma, and the limitations of the data, has not prevented estimates being incorporated into policy documents such as the NRIS.

Previous estimates of the UK Roma population

Within the UK, there have been three notable estimates of the size of the migrant Roma population (European Dialogue, 2009; Equality, 2011; Craig, 2011). Firstly, in 2009, European Dialogue carried out a mapping exercise, involving a survey to local authorities, as well as interviews and focus groups with Roma and statutory and non-statutory practitioners in areas with significant Roma populations (European Dialogue, 2009). Out of a total of 151 local authorities, 103 provided a return (a 68 per cent response rate). Almost half of responding authorities stated there was no or almost no Roma in their area. Statistical data from the 53 local authorities who indicated they did record Roma, suggested a population in England of 24,104, mainly derived from School Census figures (which exclude adults). The interviews and focus groups however, indicated much higher numbers in many locations, raising “serious concerns about accuracy of the data provided” by local authorities (ibid: 35). Consequently, the authors proposed an overall minimum population of 49,204 Roma in England, tempered by significant caveats about the underlying information. The same report took an estimate generated from members of the migrant Roma population who participated in the study and asserted that a possible population figure living in the UK could be 111,022 individuals. Furthermore, drawing on responses from Roma participants, who were asked to count the number of acquaintances, friends and family members who had migrated to the UK, a further potential estimate of between 400,000 – 1 million was asserted. Equality (2011: 23) asserts that the ‘best estimate’ of the Roma population living in the UK at that time was around 500,000. It is not clear from which data this estimate was arrived at; however, a description of this population (in terms of location, country of origin and demographic make-up) draws heavily from the European Dialogue (2009) report. Finally, Craig (2011) produced a Peer Review of the UK’s NRIS submission, reporting that ‘National estimates of the size of the UK Roma vary widely from about 100,000 to one million’ (p. ii). While he noted the disparity of estimates, he attempted a calculation based on migration trends and an average of the existing estimates – a population in the region of 300,000 individuals:

Taking the mean of a number of estimates of Roma in the EU as 11 million, and the mean number who have arrived in the UK since 1993 as 300,000, the proportion of those moving to the UK is around 2.6%, a significantly higher proportion. If there are 300,000 Roma in the UK, they would constitute about 0.5% of the total UK population… (Craig, 2011: 29)

What is clear is that previous estimates of Roma populations – whether based on analysis of existing large scale datasets, obtained from community based studies, or simply based on a number of assumptions – pose methodological issues. However, this does not suggest that such attempts should not be made or that they are not useful indicators in order to understand the nature and magnitude of the policy and service delivery effort required. However, given the various shortcomings of previous approaches to estimate the size of the Roma population, a more experimental but pragmatic approach might be appropriate.

The research approach

Data collection

The investigation of population size in this research was only one aspect of a larger project aiming to fill significant gaps in the knowledge base in relation to migrant Roma in the UK. A self-completion questionnaire was sent out to all local authorities in the UK and. respondents were invited to provide information on a variety of issues including: an estimation of the local migrant Roma population (drawing on official data or informal sources); key issues arising with regards to their work with migrant Roma; their local authority strategy in responding to migrant Roma communities; and local initiatives and projects in place in their area.

Due to the imperative to provide as comprehensive a population estimate as possible we required the response rate to be as high as possible. In partnership with an advisory group for the research – which consisted of local authorities and third sector representatives – it was decided that all local authorities would be assured of anonymity in order for them to feel comfortable that they could draw on a variety of sources (formal and informal) without fear of being singled out by local and national pressures with regards to the size of the migrant Roma population in their area. The return of these questionnaires was vigorously pursued by the research team with every local authority receiving multiple email reminders and, for the vast majority, a phone call to encourage a reply. After exhausting this approach, a sample of responding local authorities was then followed up via semi-structured interviews and their estimates, amongst other issues, checked via local NGOs.

Out of 406 questionnaires issued, 151 returns were received (37 per cent response rate). By nation these were as follows:

- England (326 sent/119 returned) 37 per cent response rate

- Scotland (32 sent/8 returned) 25 per cent response rate

- Wales (22 sent/11 returned) 50 per cent response rate

- Northern Ireland (26 sent/13 returned) 50 per cent response rate.

While the returns only covered 37 per cent of UK local authorities, those authorities that did provide data represented just under half of the total UK population (30 million people out of 63.7 million people in 2012, ONS Annual Mid-year Population Estimates, 2012). However, it was clear that only partial coverage of the UK had been achieved. Within the 151 returns, 100 did not provide numerical estimates for their respective area. Responding local authorities that provided estimates often stated that their data was anecdotal, gathered from front line workers, or based on figures from Children’s Services. Responses providing context to the estimates given bore strong similarities to the comments received by European Dialogue (2009) and Equality (2011). Additional questions in the questionnaire aimed to provide a greater understanding as to how local authorities had derived their responses; for example, their working arrangements (e.g. data and intelligence sharing practices) with other agencies. The comments received to these questions played a part in determining the methodology precisely because they made it clear that statistical data was unavailable, patchy or not reliable. For example, a number of respondents made reference to the fact that data relating to ethnicity was not always collected.

Although arguably the responses to this survey were more comprehensive than previous similar attempts, the paucity of hard data available to local authorities who responded to the survey posed the same problem faced by previous studies. This meant that no simple aggregation of numbers was possible, but it also ruled out statistical calculations based on a sample due to potential skewing arising from those authorities which responded. It was clear that if a national estimate of the size of the Roma community was to be made, an appropriate methodology could not aim for statistical accuracy but produce indicators of the types of places Roma were likely to be found and an approximate sense of scale.

The population estimate methodology adopted

The intrinsic problems in ‘counting’ UK Roma as a migrant, ‘sub-ethnic’ and marginalised group, combined with the limited number of estimates we received meant that no simple aggregation of numbers was possible. It was recognised that the methodology selected was experimental in this particular field and not without risk, but the authors were clear that any estimate was not an end point in itself; rather, an attempt to indicate where migrant Roma populations were likely to be found and some perspective on their scale (Brown, Martin and Scullion, 2013). The adequacy and accuracy of such an approach could then be ‘tested’ further in the field.

In order to achieve this place typology modelling work was applied. Lupton et al (2011: 5) describe place typologies as tools which provide users with the ‘capacity to identify groups of places that are similar to one another…which have similar conditions and outcomes although they are not geographically proximate’. They list four different models, ranging from the simple – a ranking of order based on a single variable such as the amount of social housing in a discrete area– to the complex, which aim to develop a classification on the basis of often very detailed characteristics covering fundamentally different categories: conceptual (e.g. ethnicity, socio-economic), infrastructural e.g. (housing, transport links), as well as physical (size and location). These groups of places are often recognised administrative divisions such as local authority, ward or Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) and tools all offer one or more ‘standardised variables’ or ‘base variables’, offering greater or lesser complexity as required. Examples of this include the MOSAIC tool, developed by Experian plc, now widely used by local authorities, and the CIPFA (The Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy) ‘Nearest Neighbours system’.

Given the multiplicity of factors which affect the movement and settlement of migrant Roma populations, as well as the diversity of local authorities in the UK, a decision was made to adopt a complex model, namely the CIPFA Nearest Neighbours model. This model has been used in a range of applications, but most notably by the Audit Commission to benchmark individual local authorities’ progress against similar locations during the first decade of the 21st century when every area was required to choose performance targets from a central list of indicators to form Local Area Agreements (LAAs). The most valuable reason for the choice was that ‘nearest neighbour models start with a single place and find the most similar places to it’ (Lupton et al., 2011: 13). As such, it does not require total data coverage; rather a sample can be used, which was appropriate given the response rate.

Nearest Neighbours allows the user to choose single ‘base’ area (Local Authority A) and ask the software to assess how similar this area is to other local authorities on a maximum of 27 variables. The 27 variables include fluid issues such as the age breakdown of a local area, but also more fixed variables such as the size of the local authority area, for example. What was also valuable was that the 27 includes variables whose definition is fairly stable over time such as gender or ethnicity (even if the numbers of ethnic minorities increased or declined). The degree of difference is the variance from the base local authority on a scale of 0-1. This means the nearest may vary only 0.001 from the base using the index of variables, while the furthest may be 0.999. CIPFA calculates the nearest 15, but with different cut off points. Users can also compare the base to either authorities of exactly the same administrative type or a mix (metropolitans, London boroughs, unitary authorities) or all authorities including rural districts. In relation to Brown, Martin and Scullion (2013) the following methodology was applied:

- The individual estimates supplied in survey returns (51 authorities) were taken at face value and were termed ‘primary’ estimates.

- All the 51 authorities who had provided primary estimates were entered into the Nearest Neighbours software in turn and the 15 statistically closest comparisons generated using all 27 variables, to give as close a match as possible. Those 15 could include one or more of the other 50 authorities which had provided their own estimates. The working hypothesis was that if any of the comparisons had NOT returned an estimate to the research team, because they displayed a similar typology, they might be expected to have similar sized Roma population and could be assigned a ‘working’ population of the same size. These were termed ‘secondary’ estimates. Having primary estimates in the base and among the other 14 allowed for some refinement to the secondary estimates by taking an average of all the primary estimates among the comparisons (including the base), rather than just adopting that of the base alone.

- All UK authorities were entered into the Nearest Neighbours tool in turn. They would then generate their own comparators, among which could be authorities with primary estimates, but could also include the secondary estimates generated during Stage 2. In this instance an average of both would be taken. However, secondary estimates could not be used on their own unless they themselves had been produced from at least five primary estimates to ensure the estimate was not more than two removes from a primary.

In each case the base authority was compared to similar types of authority e.g. rural districts with other rural districts. Throughout this approach there were instances where the base had no primary and the ‘Nearest Neighbours’ modelling generated no primary or secondary estimates. Where this occurred it was decided an estimate could not be produced to any degree of certainty, so a population of 0 was assigned.

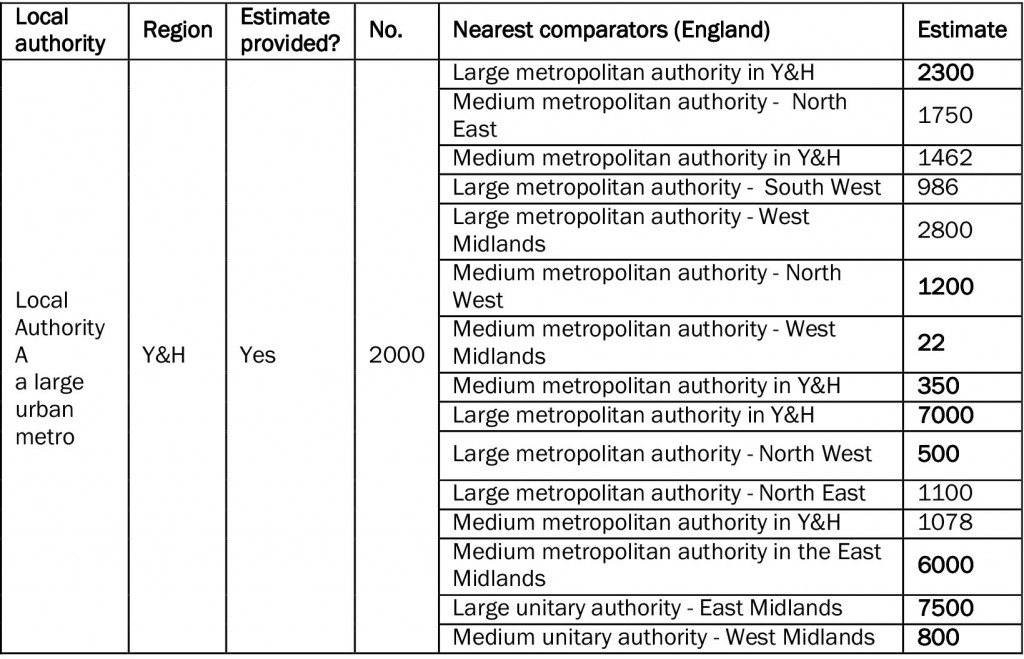

Table 1 provides an illustration as to how this approach was applied. Based on an anonymised contrived example the base authority was a large urban metropolitan borough in the Yorkshire and Humber region. A primary estimate was received of 2,000 individuals. When the ‘nearest neighbour’ authority was calculated, (in Local Authority A’s case it was compared with other metropolitan areas, London boroughs and unitary authorities in England – Scotland, Wales and NI having different systems of local government), 9 of the top 15 had also provided primary estimates (in bold), while the remainder had already generated secondary estimates reasonably comparable in number. The assumption was that similar ‘types’ of places could be reasonably expected to have similarly sized Roma populations. This was replicated for each authority throughout the exercise. Using this technique a large number of secondary estimates were generated and by adding together primary and secondary estimates an overall aggregate figure across England of the UK of 193,297 was produced. It was not possible to replicate this approach in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland due to the low number of local authorities in those nations; as such estimates obtained directly from the survey of authorities were used. Combining the estimate for England with those primary figures received from Scotland (3,030 individuals), Wales (878 individuals) and Northern Ireland (500 individuals) provided an estimated migrant Roma population size of 197,705 individuals for the UK.

Using this approach to estimate the Roma population is experimental but given the lack of adequate or reliable data on migrant Roma that exists at local and national level, a new approach was justified, and perhaps unavoidable. While this approach has not been commonly applied to assessing the size of Gypsy, Roma and Traveller populations, it is legitimately used to measure a wide range of socio-economic patterns, including the settlement of ethnic minority populations. As the authors acknowledged (see Brown, Martin and Scullion, 2013: 74-76) this approach was not without risk. The primary issue was whether it was possible to establish any empirical connection between patterns of settlement by migrant Roma and the measurable datasets in the ‘Nearest Neighbours’ tool. Simply put, are local authorities sharing very similar characteristics across the 27 indicators likely to display similarity in their Roma populations? If so, what is the basis for this? Is there evidence that Roma tend to reside in similar numbers in similar types of local authority?

This type of problem is not unique. As Harris (2013: 2282) suggests in relation to schooling, it is well known that free school meal eligibility is a poor proxy for measuring low family income as well as poverty, deprivation, or social exclusion in general, but despite such evident shortcomings it is the only measure currently used within state-funded schools and continues to operate as an indicator. More importantly, Harris notes that whilst there are valid criticisms of continuing to use such proxies, it does not automatically imply that indices are no longer useful or that it is inevitable that other methods, such as “locally focused case studies represent a superior approach” (ibid, 2285). But in one sense, advocates of alternative methods miss the point:

…we would readily agree that more idiographic and often qualitative case studies…offer important insights about what…choice actually means to people ‘on the ground’ and how they act. (Harris, 2013: 2286)

Although indices, as Harris (2013: 2287) states operate essentially as averages, they:

…emerge as the sum of their parts and can be used to identify interesting localised cases for further study…in any case, we do not want to create a competition between different methodological approaches. Instead, we simply note that judicious use of index values can motivate precisely that sort of work (i.e. more in depth qualitative work)

We acknowledge that there is a question whether the 51 estimates provided by local authorities were robust enough to be used as the baseline from which other comparisons were made, but – as yet – more effective alternative methods are rarely offered when attempting to gauge the size of communities outside traditional monitoring systems. Although a national figure is proposed, we stress its provisionality (see Brown, Martin and Scullion, 2013). An emerging outcome from this approach is the potential development of a place based model which could indicate the type of places Roma could be expected, using approximate evidence (including front line workers knowledge) from which more detailed, local studies can be undertaken. The authors invite others to take up this opportunity.

Conclusion: entering a politicised arena

Roma from across Central and Eastern Europe have been moving more easily across the borders of Member States since the expansion of the EU in 2004. Although synchronous with the general wide scale economic migration of citizens from the ‘accession’ countries from that time on, in part, Roma migration has occurred because countries of origin have not ameliorated the long standing exclusion of Roma communities or have even exacerbated such marginalisation, as liberalisation of markets and return of long suppressed ethnic hostility has exposed Roma to further discrimination. As events throughout 2013 demonstrated (e.g. the case of ‘Maria’ in Greece, various television programmes, and the media attention on the Page Hall area of Sheffield) Roma continue to be a significantly politicised minority across Europe and the UK.

Upon publication, our research generated interest and debate from a range of different parties, including local authorities, Department for Communities and Local Government (CLG), NGOs, academics, politicians and the media. Increasingly, there has been a move towards the need for research to have a ‘practical pay-off’ (e.g. its direct contribution to policy making or practice), ‘this being the other side of the requirement that policy-making and practice should be research or evidence based’ (Hammersley, 2003: 327). In order for practical pay-offs to occur, dissemination of research is essential. However, dissemination is sometimes followed by ‘distortion’, particularly in relation to media representation (see Hammersley, 2003, for example for a discussion of media representation of research on educational attainment of minority ethnic children).

A number of commentators have already highlighted examples of negative media representations in relation to migration more broadly (King and Wood, 2002), and particular groups of migrants – for example refugees and asylum seekers (Kaye, 2002) and Roma (Erjavec, 2001). Additionally, it is argued that there has been a change in journalist culture with an increasing commitment to entertainment (ICAR, 2012) or ‘infotainment’, which is described by Greenslade (2005: 10) as a ‘subtle combination’ of information and entertainment. As Greenslade (ibid: 21) suggests, contemporary media has become ‘more hysterical’, but also the stories are more repetitive in nature. Indeed, he refers to a persistent theme in the Express newspaper during 2004/2005 around a supposed ‘influx’ of Roma. It is not the purpose of this paper to look at the evolution of the media, or the historic relationship between media representation and ‘moral panics’, as these interesting discussions can be found elsewhere (see for example, Cohen and Young, 1973; Mai, 2002; Greenslade, 2005). However, it is important to note that a media focus on Roma is not a new phenomenon. More importantly, the response to the findings from this research need to be seen within the wider context of the debates around the UK’s role in Europe, immigration, and ethnic diversity more broadly, which have been a consistent feature of political, public and academic debate.

Returning to one of the core reasons for this research, namely the perceived inadequacy of the UK National Roma Integration Strategy (NRIS) and the need to highlight the challenges faced by local authorities, Roma populations and destination communities, the commentary by Fekete (2013) and the presence of a parliamentary Early Day Motion1 on the issue of Roma inclusion are encouraging. Such statements and support for positive action on the inclusion of Roma in the UK provides hope that the marginalisation and discrimination, from which many Roma are fleeing, may be not be a defining feature of their lives in the UK.

1 Early Day Motion 788 ‘Roma Migrant ‘Communities.

Philip Brown, Sustainable Housing & Urban Studies Unit (SHUSU), University of Salford, M5 4WT. Email: p.brown@salford.ac.uk

Amnesty International (2011) Briefing: human rights on the margins, Roma in Europe. London: Amnesty International.

Bartlett, W., Benini, R. and Gordon, C. (2011) Measures to promote the situation of Roma citizens in the European Union. Report for the European Parliament. Brussels: Directorate-General for Internal Policies, Policy Department C Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs.

Brown, P., Dwyer, P. and Scullion, L. (2013) The Limits of Inclusion? Exploring the views of Roma and non Roma in six European Union Member States. Salford: University of Salford.

Brown, P., Martin, P. and Scullion, L. (2013) Migrant Roma in the United Kingdom: Population size and experiences of local authorities and partners. Salford: The University of Salford.

Clark, C. (1998) Counting Backwards: the Roma ‘numbers game’ in Central and Eastern Europe. Radical Statistics, 68, 4.

Clark, C. and Greenfields, M. (2006) Here to Stay: The Gypsies and Travellers of Britain. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press.

Cohen, S. and Young, J. (1973) (eds) The manufacture of news: social problems, deviance and the mass media. London: Constable.

Craig, G. (2011) The Roma: A Study of National Policies. Brussels: European Commission. Available online at: http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/research/pdf/EURoma.pdf (Accessed 06/03/2014).

Craig, G. (2013) Assessing the implementation of National Roma Integration Strategies: Ad hoc request. EU Network of Independent Experts on Social Inclusion: York Workshops.

Department for Communities and Local Government (2011) Commission Communication: An EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies up to 2020. Available online at: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmeuleg/428-xxvi/42809.htm (Accessed 10/03/2014).

Department for Communities and Local Government (2012) Progress report by the ministerial working group on tackling inequalities experienced by Gypsies and Travellers. London: HMSO.

Equality (2011) From Segregation to inclusion. Roma pupils in the United Kingdom, a pilot research project. Available online at: http://equality.uk.com/Education_files/From%20segregation%20to%20integration_1.pdf (Accessed 10/03/2014)

Erjavec, K. (2001) Media Representation of the Discrimination against the Roma in Eastern Europe: The Case of Slovenia. Discourse & Society, 12, 6, 699-727. CrossRef link

European Commission (2010) Roma in Europe: The Implementation of EU Instruments and Policies for Roma Inclusion – Progress Report 2008-2010. Commission Staff Working Document. Brussels: European Commission. Available online at http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=4823&langId=en (Accessed 13/04/14).

European Commission (2011) An EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies up to 2020. Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Brussels.

European Dialogue (2009) The movement of Roma from new EU Member States: A mapping survey of A2 and A8 Roma in England, report for the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF). Available online at http://equality.uk.com/Resources_files/movement_of_roma.pdf (Accessed 10/03/2014)

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2009) EU-MIDIS Technical Report: Methodology, Sampling and Fieldwork. Available online at http://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu-midis_technical_report.pdf (Accessed 10/03/2014)

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2014) Roma Pilot Survey – Technical Report: Methodology, Sampling and Fieldwork. Available online at http://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/roma-pilot-survey-technical-report-methodology-sampling-and-fieldwork (Accessed 10/03/2014)

Fekete, L. (2013) A review of the Migrant Roma in the UK research report. Institute of Race Relations. Available at http://www.irr.org.uk/news/no-going-back-for-the-roma/ (Accessed 24/02/2014).

Finney, N. and Simpson, L. (2009) ‘Sleepwalking to segregation’?: challenging myths about race and migration. Bristol: Policy Press.

Greenslade, R. (2005) Seeking Scapegoats: The coverage of asylum in the UK press. Asylum and Migration Working Paper 5. London: Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR).

Hammersley, M. (2003) Media Representation of Research: The case of a review of ethnic minority education. British Educational Research Journal, 29, 3, 327-343. CrossRef link

Harris, R. (2013) Are indices still useful for measuring socioeconomic segregation in UK schools? A response to Watts. Environment and Planning A, 45, 2281–2289. CrossRef link

Hillygus, S., Nie, N., Prewitt, K. and Pals, H. (2006) The Hard Count: The Political and Social Challenges of Census Mobilization. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

ICAR (2012) Asylum Seekers, Refugees and Media, ICAR Briefing, February 2012. Available online at http://www.icar.org.uk/Asylum_Seekers_and_Media_Briefing_ICAR.pdf (Accessed 25/02/2014).

International Labour Office (ILO) (2012) Hard to see, harder to count: Survey guidelines to estimate forced labour of adults and children. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Irish Traveller Movement in Britain (2013) Gypsy and Traveller population in England and the 2011 Census. London: Irish Traveller Movement in Britain. Available at http://irishtraveller.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Gypsy-and-Traveller-population-in-England-policy-report.pdf Accessed 07/03/2014.

Kaye, R. (2002) ‘Blaming the victim’: an analysis of press representation of refugees and asylum seekers in the United Kingdom, In: R. King N. Wood (2002) (eds) Media and Migration: Constructions of Mobility and Difference. London: Routledge, pp. 53-70.

King, R. and Wood, N. (2002) (eds) Media and Migration: Constructions of Mobility and Difference. London: Routledge.

Lupton, R., Tunstall, R., Fenton, A. and Harris, R. (2011) Using and developing place typologies for policy purposes. London: DCLG.

Mai, N. (2002) Myths and moral panics: Italian identity and the media representation of Albanian immigration, In: R. D. Grillo and J. C. Pratt (eds) The Politics of Recognising Difference: Multiculturalism Italian Style. Research in migration and ethnic relations series. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 77-94.

Minister for Human Rights (2009) Roma Integration Concept for 2010-2013. Available online at http://ec.europa.eu/justice/discrimination/files/roma_czech_republic_strategy_en.pdf (Accessed 14/04/2014).

Niner, P. and Brown, P. (2011) The evidence base for Gypsy and Traveller site planning: a story of complexity and tension. Evidence & Policy, 7, 3, 359-77. CrossRef link

ONS (2014) Quality of Long-Term International Migration Estimates from 2001 to 2011. Available online at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/method-quality/specific/population-and-migration/international-migration-methodology/quality-of-long-term-international-migration-estimates-from-2001-to-2011—full-report.pdf (Accessed 14/04/014).

Open Society Foundations (2011) EU Policies for Roma Inclusion. Policy Assessment. Available online at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/2011-07%2520EU%2520Roma%2520Inclusion%2520Policies%2520final.pdf (Accessed 07/03/2014).

Open Society Foundations (2013) Roma Census Success. Factsheet. Available online at http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/fact-sheets/roma-census-success (Accessed 06/03/2014).

Reding, V. (2012) The Commission’s Communication on “National Roma Integration Strategies: a first step in the implementation of the EU Framework. Speech/12/379. Available online at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-12-379_en.htm (Accessed 10/04/2014).

Scullion, L. and Brown, P. (2013) ‘What’s working?’: Promoting the inclusion of Roma in and through education. Salford: The University of Salford.

Sigona, N. and Hughes, V. (2012) No way out, no way in: Irregular migrant children and families in the UK. Oxford: COMPAS.