We are delighted to share the first discussion in our podcast series with Janet Bowstead. Janet spoke to us about her research around ‘journeyscaping’ women’s moves to escape domestic abuse in England. Her qualitative work with women in refuges and analysis of administrative data from support services has shed light on some of the individual and system-led drivers of decisions to remain in place or relocate as a result of domestic abuse.

PPP published a paper by Janet exploring the scale of movement across regions in 2023, and in this podcast Janet joins us to discuss this work.

Additional research reports, visual outputs and resources from Janet’s research can be found on her website.

Listen to the podcast now and follow us on LinkedIn for news of the next release.

Emma Bimpson [00:08]

Hello and welcome to our first People, Place and Policy podcast. True to the ethos of the journal, we are branching out into audio to make our content more accessible.

Our first guest in the series is Janet Bowstead, author of a paper published in PPP in 2022, entitled ‘Journeyscapes, the regional scale of woman’s domestic violence journeys’.

Our conversation was recorded earlier this year, and you can read the paper in full and find a number of other resources from the project on the PPP podcast page.

I’m just going to give a quick overview of some of Janet’s work. Janet has got a long professional background in frontline work policy, Janet’s worked in women’s refuges on helplines, she’s worked with local government in policy and practice development right through to training professionals. Janet’s research spans areas of geography, social policy, sociology, it integrates quantitative, spatial, qualitative and creative methods.

And more recently, in the project that Janet will be talking to us about today, Janet’s work involves mapping national administrative data to participatory photograph work with women who have been relocated due to domestic abuse. So, there’s some really rich and interesting methods that Janet will be talking to us about today. So, Janet’s going to be talking to us today about her British Academy post-doctoral Research Fellowship project, which was called ‘Women on the move Journeyscapes of domestic violence.’

This was based at the Department of Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London. So, without further ado, Janet is going to introduce her PPP paper and I think throughout you’re going to be referring to a number of maps that support the work and some other resources and again, those will be hosted on our PPP podcast page, so you’ll be able to see all of those there.

Janet, do you want to tell us about your – give us a bit of a summary of your PPP paper?

Janet Bowstead [2:13]

Sure. Yes. Thank you very much. So yes, my research is around women relocating due to domestic violence and abuse.

And one of the things that I’m doing is using the framing of internally displaced persons, seeing that individuals who are forced by the human rights violation of violence against women to relocate within a country, but across administrative boundaries, seeing them as internally displaced persons.

To turn the focus really onto the state’s responsibilities rather than just seeing these as lots of very individualised things that that need a welfare response. So, thinking about the, obviously the losses and the harms that are caused by the abuser in intimate partner violence, but being compounded by the losses and the harms which are caused by the state. And particularly this issue of crossing local authority boundaries within the same state.

So, what I was able to do was use administrative data from services which existed England wide for a period. Which is that, you know, a safe way of uncovering these hidden journeys, these abused women, you’re escaping a violent partner. Very hidden, very secret for very good reasons. Unfortunately, the data are no longer available countrywide, so we cannot now sort of analyse the journeys between local authorities, but what I was able to do with this, this large data set was kind of the mapping in every sense of the scale.

The scale in terms of numbers, we’re talking about 10s of thousands of women and children and the wider research involves the individual stories and photography by women themselves who’ve relocated. So, remembering that behind, you know, every line on a flow map every number, there’s individual women’s experiences and insights.

But working at this scale with the administrative data means it can think about geographical scale and from mapping these boundary crosses, discovering how un-self-contained local authorities are.

A third of service contacts for someone you know seeking help you know, because of domestic violence and a half of all those that are involving relocation being from a different local authority, so just to put some figures on it, you know, for one year 25.5 thousand cases of a service access for the primary reason of domestic violence, 31% was staying put and accessing support, so they weren’t going anywhere, but they were accessing service support. 32% remaining local, so staying within that local authority but relocating and 37% going elsewhere, crossing a local authority boundary.

And so that’s, you know, not how policy and law deals with the issue of domestic violence. It treats local authorities as if they’re self-contained. National government, you know, divorce responsibilities both for assessing needs and for providing for service needs to local authorities.

And so you’ve got this real mismatch and the real risk of perverse incentives for local authorities because they’re carrying out the needs assessment. You know, if they don’t provide any kinds of services or anything that means somebody could cross a boundary to access the service. Then it’ll look like there’s no need because you can’t present from elsewhere if the provision isn’t there.

Emma Bimpson [6:02]

Thanks, Janet. That’s a really clear overview.

I’ve got a question about the sort of the journeys that you’ve mapped there and within the figures that you presented. So, the proportion of people who stayed put gone elsewhere etcetera. Within that, some of those journeys might be the same women, I presume, so the same women and families who might have had to present on numerous occasions.

Janet Bowstead [6:32]

Yes. So, what I’ve been able to do in other parts, it isn’t particularly touched on in the PPP article, is to do some linking so the data are de-identified which makes it safe to use them. But for part of the time there was a variable that could be linked to identify the same individual who might have multiple service access and multiple gaps between service access, and that’s a minority in terms of the time frame of the data because that’s only there for under four years of the data.

But yes, so that was it was possible to look at multiple service access, but a lot of the time in terms of what’s in the record, it’s like just the one service access. But one of the other things that I kind of mapped was sort of the two stages.

So yes, so one of the kind of flow diagrams that I’ve produced maps two of the journeys. So, the local authority before accessing a service, the local authority of the service and the local authority, after leaving of the service, because that again was recorded in the administrative data. So, you see basically journeys from everywhere to everywhere. There’s kind of fewer local authorities in the middle because not every local authority provides services.

But in terms of from and to just those two stages every local authority in England and also comes from Scotland and Wales and elsewhere. So yes, that I mean that’s there are multistage journeys and that raises obviously even more complexity in terms of working directly with women about their experiences again have been able to do journey graphs of multiple relocations and gaps, and maybe resettlement and then having to move again. That’s definitely part of the story.

Emma Bimpson [8:35]

One of the things that I found really interesting about your paper, and I know you’ve talked about it more in previous papers, is that the kind of perverse incentive that’s created in the way that assessments are done and in the way that women present when they are seeking support from, you know, through safe accommodation.

I wondered if you could just explain a little bit more about that in terms of how it works and how it might sort of impact our understanding of need.

Janet Bowstead [9:04]

Yes, I mean that is either the starkest example of the mismatch between what the state chooses to do in terms of how it responds to domestic violence and what you would actually do if you were designing a system that met women and children’s needs and rights. So always, you know, all kinds of governments over the years have devolved responsibilities to local authorities.

And as I said, you know, local authorities just are not self-contained. And so there’s this real, you know, tension there because in terms of local authorities, including somebody in their assessment, the person’s actually got to sort of manage to turn up there and they’re only really going to manage to turn up there if they’ve found a service there, they’ve been able to sort of get a place in a women’s refuge or a homeless hostel or something like that.

You know, local authorities, if they don’t provide any of those kinds of services, they’ll actually appear to have a low level of need because they haven’t provided for anyone to go there. So that’s been the case always in terms of how local government and national government have interacted, as I said, it’s been really compounded most recently by the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, which was highlighted as if it was really going to sort of be a much better way of sort of tackling these issues and it just still doesn’t address what’s actually going on in terms of relocation.

So, Part 4 puts a new duty, which sounds like that’s good, that’s strengthening things, that’s going to make things better, but it puts it on the local authorities. So, in terms of partnership arrangements and provision of safe accommodation, including women’s refuges on tier one local authorities.

And regardless of what their neighbouring authorities do, so you know what my research with these administrative data from an earlier period show is that is that local authorities are just not self-contained. So that having a local authority scale of policy and provision creates these cliff edges at each boundary, which increase the losses and harms of the women and children who have to cross them.

So, in the paper that I did for PPP, I was looking at, well, what might be a more functional scale. And I looked at regions and the most self-contained region is the northeast of England, which is 93%, but there’s still boundary crossing to other regions and from other regions. The least is London, which is only 75% self-contained and so you know 25% leaving and arriving.

What’s really ironic and shows how the Domestic Abuse Act is not evidence based, is that the least self-contained region, London, is actually recognised within the Act as the scale for planning purposes. So London is treated as a region for partnership and safe accommodation, even though it’s the least self-contained region and the others, it’s all at the local authority level again so these cliff edges that women and children you know fall off between neighbouring authorities, you know, evidence was presented to government in the development of the bill and everything and not addressed.

So, it’s just not based on the evidence which is not based on a on a rights-based thinking because a rights-based duty would ensure that there’s no service eligibility criteria based on location at any stage.

There’s no reason based on location where you’re from, where you’re going to, that should affect your eligibility to services, but that’s not what we choose to do as a state. That’s not what we’re doing as state.

So, you need sufficient capacity. You need different types of services. Yet specialist women’s refuges, non-accommodation services, you need the range of different things across all the country, in all types of locations, but the system that we have actually is creating additional harms and losses over and above those that are caused by the perpetrator.

Emma Bimpson [13:33]

Yeah. And I see in your PPP paper you referred to the domestic abuse Commissioners offices report, which has now been published, I see, and that there’s some interesting data in there around different types of services available.

And but of course your paper is focused primarily on accommodation-based services. So, services are considered safe accommodation. And I think that your human rights framings are really valuable way to kind of highlight just how stark this problem is. I wondered with all of the incredibly rich data that you’ve collected through discussions with women and through the creative methods that you used, did your conversations highlight any more about how those moves were taking place. So obviously there’s a primary issue around the resource that’s actually there. But from speaking to women who participated in your research, what did you learn about the decision-making process and what factors were driving those moves to different locations?

Janet Bowstead [14:41]

Enormously diverse. I think that’s the really sort of important thing to emphasise is that there’s no right journey that should or shouldn’t be made. You know, if you’re coming from a framing of you’ve already experienced human rights violation of this violence, this threat, this abuse. The State should not be making anything any worse for you, so there should be no barriers basically, you know, eligibility barriers, capacity barriers, logistics, you know, can you afford the train fare all those kinds of things to stay put if you can, to be local if you can, to go hundreds of miles away, you know it should be whatever it is that you need to do.

You’ve already been harmed by the abuser and the state should now be putting all the infrastructure in place to minimise any further harms and that’s really not the case. You have these multiple sorts of barriers or lack of options or lack of control over.

I mean both timing and place, yeah, that comes up really strongly from women’s experiences that you know, sometimes they’ve had to relocate in a crisis and then they’re sort of stuck, immobile, but knowing that they’re going to have to move again. But they don’t know when and you know it goes on for months and months and sometimes that can be really positive time of, you know, rebuilding your sense of self, your children and working out what you want to do next where you want to be. Maybe you want to, you want to make another move to an area that’s more suitable for you. You went to some place in crisis and then you actually think, well, where do I want to try and start again? Where would be the best place for me to start again?

But you have very few options and very little control, and then suddenly if you’re relying on, say, local authority rehousing. If that happens, when it happens, it happens very suddenly, so you can have been months and months in a place and then suddenly you’re supposed to move by Tuesday, to another place and, you know, can you hire a removal van? Can you pack up your stuff? What on earth are you going to do? What do you do about the nursery? The school?

And then you know, while you’re in limbo, you think, do I try and do some study? Do I not? Do I enrol anywhere? Do I get on a waiting list for something? All those kinds of things, so there is, you know, forced immobility and this force and this lack of control over the timing and the place makes it so much harsher than it needs to be.

You know, some of those moves would be what you want to do and you end up in the kind of place you want to be, but how you’d plan it if you had any control over it is completely different from how it happens for most women, so very, you know, abrupt very out of control. And when you’ve been in a relationship where there’ll be issues of control and abuse and that kind of thing, you can suddenly be under other control under effectively sort of, you know, authorities control state control and still having no say in what happens.

Emma Bimpson [17:58]

Yeah, absolutely. You can really see how these systems and processes can be re-traumatising to people who’ve already been affected by domestic abuse and other situations. I wondered in all of the discussions that you had with your participants, did you come across any positive or more positive ways of working that did support women to make choices that allowed families to have more control over the situation?

Janet Bowstead [18:31]

So yes, I mean the main thing was something that sort of minimised these barriers really. So, anything that sort of worked across boundaries made a real difference, because what can tend to happen is that even, you know, voluntary sector support services are local authority funded, and they’re not allowed to support anyone from outside the area.

So again, you can have a complete cliff edge from that, you’ve been working with a key worker or support worker or an advocate, you know, for a period of time and then you move, not necessarily very far in mileage, but if you’re crossing a boundary that worker can’t support you anymore because that’s the eligibility criteria that’s put on the funding.

Where there were, you know, funding programmes that enabled a wider area across boundaries across, you know, maybe the whole of a county if you’re talking about, you know, different local authorities in, in more sort of rural areas and where the support could do that continuity through that enormous upheaval of moving, and even if it’s a positive move, you know to settled accommodation or something, it’s still hard work moving and so if you could have that continuity, so where there was, there’s eligibility to have that continuity and they could support you for another three months or even six months or something in the new place that made such a difference, and because it wasn’t this sort of brutal cut off at the time when you needed the most.

Emma Bimpson [20:07]

Yes, yeah, I suppose it’s allowing flexibility in funding and commissioning not only of the accommodation-based support, but the floating support or whatever else the support provision is.

Janet Bowstead [20:21]

Yes, I mean it’s about actually saying that the infrastructure is supposed to meet women and children’s needs. It’s not being done for the benefit of the authorities or the funders. You know, who’s it for?

But it is about, you know, this fundamental thing – if you devolve things to local authorities, it’s just a mismatch. It’s just a mismatch.

So, you know, that’s why you end up with everything with these really rigid boundaries around it. I mean, that’s the kind of the idea of the journeyscapes that obviously I put into the title of the article.

Is saying that the current, you know, journeyscape for women and children is fragmented, is hostile, it’s unnecessarily difficult to navigate. That’s what she faces when she’s having to relocate.

But it could be journeyscaped by law and policy and provision to say we should actually build an infrastructure, not little pockets of good practice, bad practice, this that and the other, an infrastructure that actually ensured a more effective response that was based on rights and needs across wherever you need to go.

And yeah, that infrastructure also makes it possible to stay put because you can only, you know, try and stay put and hope that he’ll be held accountable for his violence and abuse, his threats. You’ll be able to say, stay put safely if there would be an alternative, if you needed to escape, you know, if there’s no alternative you’re not staying put, you’re just imprisoned.

So, everybody needs an infrastructure for relocation to some extent so that you don’t have to relocate. You know, we all need it so that you can make some real choices, but yeah, the idea that being a coherent infrastructure is so far from what we have at present, it’s got pockets and cliff edges and this hostile, or an environment that you can’t even make sense of.

You just don’t know what you could do. You don’t know what your rights are, and nobody’s with you on that journey, no one’s signposting you, no one’s giving you a lift, no one’s helping you in practical ways, but also in emotional ways to have some continuity in the journey that you’re having to make.

Emma Bimpson [22:56]

Thanks, Janet. That’s a really clear overview.

Janet Bowstead [22:59]

I think that’s it. I mean, obviously we all want a system that holds perpetrators accountable for their abuse and so that nobody’s being forced to flee. That’s not where we’re at at present. So, where we are at at present, we need to be doing all these things. So, all the authorities that should be attacking the perpetrator should be doing more.

But in the meantime, because the other thing can be that if you, you know, flee and relocate at that moment of crisis, because that’s your only option, you can end up finding that the authorities treat you as having sort of burnt your bridges.

And so that if you work out that you could return back or fairly local or whatever, obviously some local authorities may have a couple of different towns within them and you think, well, maybe I could be in a different town or within the same local authority, once you’ve done that initial move, you can’t get back either.

So, nothing’s geared up to you being able to make informed choices, because sometimes you have to flee and escape before anybody starts telling you what on earth rights you’ve got because you’ve been kept isolated in that relationship. And he’s saying to you, no one’s going to help you if you if you leave. If you leave and you find out that people are going to help you with that information, you can work out what you could do and what would be right for you, and then you can find out that again, it’s being blocked by the authorities. It’s not being not to do with him, now it’s the authorities saying that you can’t make your informed choices.

Emma Bimpson [24:29]

I think the way that you’ve sort of conceptualised this messiness through journeyscapes is applicable to so many different authorities. So of course the primary one being the level of funding and administration and provision of safe accommodation that needs to be considered at, at least the regional scale, but really national scale so that you don’t come across these hurdles, so that the moves can happen as they need to as quickly as they need to, but then something you just touched on there was about the fact that women and other survivors can be sort of penalised for making the moves that they need to do.

So, I’m thinking about housing authorities, social housing. If someone was to abscond their tenancy, if someone was to temporarily leave to, you know, take themselves out of danger.

It’s not necessarily easy to go back because you have, you know, technically absconded your tenancy. You might not have been paying your rent for a for a short time because of this period of crisis that you’re in. So, I think this kind of the, the concept of journeyscapes and journeyscaping, is such a valuable way of understanding for a whole range of different services.

Janet Bowstead [25:43]

So yes, I mean like all kinds of systems, none of us know how they work until we actually have to try and use them. And then we find out whether the kind of theory is the same as the practice and if you’ve been isolated in a violent and abusive relationship, you’re even less likely to know how the system works or what your rights are. So, at that escape that might be your first opportunity to find out anything about that.

But as you said, at that point you may have given up a tenancy because you just didn’t know what you could do. You didn’t know there was possibility of actually having rent paid on two places for a period of time to retain a tenancy.

There’s been, you know, notions about should there be if you had a secure tenancy, can you still get another secure tenancy? But if there’s been any kind of gap that’s treated as well, well that’s the end of that. And you’re now on a new you know, temporary tenancy and not a permanent tenancy and things like that.

So yes, I mean, housing rights, but all sorts of other things in terms of your college, your study, your work, your career. You know, if you’re a nurse, you have to keep your registration up to date. If you let that lapse, you have to re-train again. All those things that can lapse because of, you know, what’s been done to you. We shouldn’t be setting up a system that harms you even further beyond the initial harm.

Emma Bimpson [27:09]

No, absolutely. I could happily speak to you all day about this research, but unfortunately, we are going to have to bring the conversation to a close.

But before we finish, I wondered whether you had any plans for taking the research further, because it feels like there’s just, you know, so much opportunity for further research and understanding these issues, I wondered if you’d had any more projects or any more plans to develop the project?

Janet Bowstead [27:40]

It’s interesting because the big picture, as I said that this administrative data that the 10s of thousands that the maps with these flows, you know all across the country from everywhere to everywhere can be a very powerful message, that indicates the scale. But that is simply not possible because there’s no gathering together of the data anymore in any kind of consistent way, so that it’s done by local authorities. So, you just can’t see any of these journeys across local authorities, so that simply isn’t possible, because again of how we choose to collect data or make data available as services are often, you know competitively tendered for. There’s real risks for services to share their data, you know, with their competitors and all those kinds of things.

So, we’ve created a, you know, wilful ignorance of what’s going on beneath the services sort of churn beneath the surface. So, anything we can do now in terms of that mapping is on a much, much more limited scale.

But we can still sort of feed some of that into. I mean things like, you know, some of the provisions of the Domestic Abuse Act are only just starting to be enacted or being evaluated or whatever. So keeping on feeding that into to what’s going on with, with what local authorities doing you know is part of the process that I’m involved in, but the law is so fundamentally flawed in terms of devolving to local authority, this is very difficult to see how that can be influenced when that, political decision has already been made to not take national responsibility and to devolve it to local authorities.

Emma Bimpson [29:30]

Thank you, Janet, for being our first guest and we hope that our listeners have enjoyed the podcast. You can read Janet’s paper and some of the other outputs from her project on our podcast page. We’d also like to thank our listeners and we’ll be back with more of our contributors soon.

Read Janet’s PPP paper, ‘Journeyscapes: the regional scale of women’s domestic violence journeys’

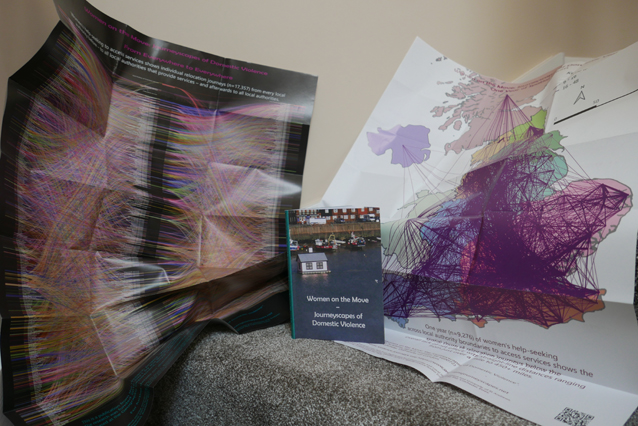

Download a flow map, ‘Women on the Move: Journeyscapes of Domestic Violence One Year of Spatial Churn’

Download a flow diagram, ‘Women on the Move: Journeyscapes of Domestic Violence from Everywhere to Everywhere’