Abstract

Research on positionality and accessing field work for researchers studying their own communities in Lower Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) is scant. The majority of the literature on this topic emanates from High-Income Countries (HICs). Drawing on ethnographic field work conducted in Kenya and Pakistan, the authors have explored ways in which dialectic relationships between the researcher and participants in various social spaces (SSs) within the place of research (PoR) influences access to the field and data quality. The authors analysed reflective narratives from their fieldwork using Gibbs’s Reflective Cycle (GRC). The findings show that, accessing field work in LMICs where the research agenda is not fully developed with respect to funding and government support presents not only social and practical issues concerning the fieldwork but also ethical dilemmas. SSs in a PoR are powerful in determining both access to the field and data quality. For researchers returning from HICs to study the communities of their origin, being a native does not grant automatic access to research spaces. Gender and power dynamics are not only crucial for accessing the communities which are studied and from which data are collected but can also bring a degree of bias to the data collected. This paper sheds light on issues around positionality, access and doing field work in these contexts. The findings show the complex context in which research is conducted and how positionality is contested. This paper is useful for professionals from LMICs, early career researchers and professionals working in international development.

Introduction

Researchers in various academic fields have conducted research and provided authoritative data which have been used for policy formulation, service improvements, behaviour change and the development of intervention tools. In most of these studies, although the researchers have been quick to point out the limitations of their research or potentials and barriers, they have rarely explained how their multiple identities in various social spaces (SSs) within the place of research (PoR) affect the data which they collect. By large, debates on positionality has focussed on the role of researchers considered as ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders. Such studies on field ‘positionalities’ has often focussed on the researcher’s differences and similarities as a facilitator for accessing field participants, or how their study participants either accepted, rejected or redefined their (the researchers’) identities (DeLyser, 2001; Jacobs-Huey, 2002; Chavez, 2008). Social scientists are increasingly concerned about how their positionality and background might shape the research process from the design, methodology, data analysis and challenges they face in the field as either researcher ‘insiders’ or ‘outsiders’.

The existing literature on the positionality recognise that researcher’s stance/position in relation to wider social, political and cultural context of the research study – the setting (place of research), social spaces, the participants, do influence the entire process of research from the construction of the research question to dissemination of the findings (England, 1994; Alcalde, 2007; Coghlan and Brydon-Miller, 2014; Huisman, 2008). The positionality is not a unitary concept, but a multidimensional process, in which a researcher may be closely positioned on some aspects and not on others. These variations can impact by altering the research process, creating tension in the relationships between the researcher and the participants and changing the study findings (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller, 2014). For instance, Huisman (2008) states that during her fieldwork with Bosnian women, she identifies herself with them as a woman, friend and confidante but she discovered the participants women were on different positions in terms of their life experiences, goals to make a life within refugee families but the common value she found was being a woman that helped her to foster the relationships with the participants as an insider. In the similar vein, Bourke (2014) in his study to explore experiences of black students in a predominantly white university, being a white man, he expected to connect with the white students more easily, but what happened was the opposite. The white participants were reluctant to speak with the researcher as compared to the black participants, who were more open to talk. In Bourdieu’s perspective the field is an arena in which struggle over capitals occurs like a ‘game’ between contestants who hold positions depending on the skills and knowledge (resources) they have (Brosnan, 2010). Similarly, a researcher struggles to align one’s positionality in the ‘field’. We used the concept of field in our research as social spaces of production, reproduction, and exchange of knowledge, and the struggles of positions held by the researcher and the participants for generation of knowledge (Swartz, 2016). In the social spaces various types of tensions are faced by a researcher, the most common is ‘outsider and insider’.

Debates in the existing literature about researchers considered as ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ has shown that, both researchers can bring a degree of biasness in research (Dwyer and Bukle, 2009; Acker, 2000; Narayan, 1993). Scholars have argued that there is no better or worse standpoint in research as both approaches requires openness, honest and a critical reflection on the field work process with respect to how participants experiences are presented, how data is analysed and how results are presented (Fay,1996; Armstrong, 2001). Unlike the ‘outsider’, – an ‘insider’ researcher shares common characteristics, experience and roles with the research participants (Dwyer and Buckle, 2009). These commonalities are assumed to facilitate the research process in terms of acceptance, trust, openness and depth of the data gathered. Yet, just like ‘outsiders’, not all researchers who are considered as ‘insiders’ can be assumed to understand the sub-cultures of the communities in which they live, and thus, they may be considered as ‘outsiders’ in their own communities (Narayan, 1993; Acker, 2000). Being an ‘outsider’ or ‘insider’ can be fluid as participants can put labels on researchers based on their gender, education status, age, marital status, communication competency, class, caste background and family relations (Jacobs-Huey, 2002; Narayan, 1993).

Conversely, disadvantages of researchers considered as ‘insiders’ are well reported in literature (Dwyer and Buckle, 2009; Angrosino,2005). Research on positionality have shown how the insider approach and doing native research process can be influenced by issues of place, culture and identity (Jacobs-Huey, 2002; Apparadurai, 1988; Narayan, 1993). Insiders position can be detrimental to the research process as a researcher can be clouded by his cultural familiarity to the group thus making it difficult to critically understand issues under study. Similarly, research participants are unlikely to delve into their experiences fully on assumption that the researcher already understands them (Armstrong, 2001; Watson, 1999). Since both the ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ position have a degree of biasness particularly in representing participant’s experiences, there has been a call for all researchers to adopt a postmodernism methods in approaching fieldwork and interpreting data by understanding the researcher’s context in terms of language, social cultural norms, gender, class and ethnicity (Hall,1990; Dwyer and Buckle, 2009; Acker, 2000).

Social Spaces and Place of Research

In this paper, the authors define SSs as micro places which exist within a larger, macro PoR and are multi-dimensional fields of force – the system of relations, alliances and power struggles (Bourdieu, 1990). A PoR is the physical definitive area/perimeter or the geographical area defined in the study. SSs are therefore within a PoR and are spaces where researchers’ positionalities are defined by the participants, knowledge is produced and reproduced, relationships are formed, and meanings are constructed. The SSs in this current paper also represent spaces where participants have control and agency and demonstrate signs of familiarity. These spaces may be static to the participants, but the researchers’ positionalities or their presence change the ways in which both subjects adjust. Thus, the fluidity of these spaces is created and recreated within the PoR and it is unique because it facilitates research in different ways. This paper is based on the reflections of three authors: AL is a Kenyan-descent medical anthropologist who was living in USA at the time of her research and currently lives in Kenya and the UK. Her reflections in this paper are based on her research study exploring the gender impact of water and sanitation in the slums of Kibera in Kenya. SB is a trained social anthropologist and public health professional of Pakistani origin who currently lives in the UK. He drew this account from his PhD fieldwork on the sensitive and politically charged issue of honour-related violence in Pakistan. KM is a Catholic priest of Kenyan origin and currently lives in Kenya. He provided his insights in this paper from his involvement as a representative of the Catholic Church in peace building prior to the 2007/08 Post-Election Violence (PEV) in Kakamega County in Kenya. In this paper, the authors discuss issues around accessing the SSs in which researchers work and the power which SS can have on the quality of the data obtained.

The following sections present first a summary of the three authors and their research sites; second, the methods and data analysis using Gibbs’s (1988) reflective approaches; third, the authors’ insights from the field; fourth, discussions and finally conclusions.

Authors and Research Sites

Author 1 is a medical anthropologist by background and a native Kenyan. She lived in the USA for four years before returning home to conduct her doctoral research. Her ethnographic study was designed to determine the differential gender impact of water and sanitation in the slums of Kibera. Influenced by theories of the political economy of health (Minkler et al., 1994; Rice, 1998; Stiglitz, 2002; Shutt, 1998) and the work of Paul Farmer on structural inequality in Haiti (Farmer et al., 2004; Farmer, 2005), the purpose of her research was to provide insights which could inform policy. Kibera’s slums are constructed in an area with a population of slightly over one million people living on approximately 255 hectares and are extremely overcrowded. The majority of the population is unemployed, households are single-headed, and the feminisation of poverty is very real (Government of Kenya, 2000; World Bank, 2004; 2005). Infrastructure is poor, coupled with poor and inadequate sanitation facilities: trenches filled with household and human waste, and a low ratio of gender-sensitive pit latrines to the population (World Bank, 2004; 2005). Water is scarce and expensive and water sources there are contaminated with human waste (Peters, 1998; Thompson et al., 2001; Lusambili, 2008). The slum is divided into nine ethnic villages with clear but informal boundaries only known to the residents. From an outsider’s point of view, the slums appear homogeneous, but they are actually culturally heterogeneous with their own informal leaders and very stringent rules. SSs vary on the basis of on ethnic affiliations and each ethnic group might occupy spaces based on a clan or on economic activities.

Author 2 conducted fieldwork on honour-based violence (HBV) in a southern province of Pakistan in the summer of 2016 as part of his PhD project. The purpose of the research project was to understand the community perception of the concept of honour and its relations with honour killings of women and girls in the wider socio–cultural, economic and political context. The study was informed by theories of honour (Campbell, 1964; Pitt-Rivers, 1965; Peristiany, 1965), patriarchy (Hunnicutt, 2009), and feminist political economy frameworks (True, 2012). The research site was a junction where the borders of three provinces of Pakistan, Sindh, Punjab and Balochistan, meet. This region is notorious for the murders of women and girls by their family members for the sake of saving or restoring family honour, a phenomenon which is commonly known as ‘honour killings’. In local languages of the region honour killings are known as karo-kari in Sindhi, kala-kali in Punjabi/Seraiki and siyahkari in Balochi.

HBV or honour crimes include a range of harmful practices such as domestic abuse, violence or death threats, sexual and psychological abuse, acid attacks, forced marriage, forced suicide, forced abortion, female genital mutilation, assault, blackmail, marring and the disfigurement of organs, and being held against someone’s will (Hester et al., 2015; Iranian and Kurdish Women’s Rights Organisation, 2014; Nesheiwat, 2005). The perpetrators usually kill a woman, or a girl perceived as having brought shame or dishonour to the family, clan or community (Bhanbhro, 2015). Perceived shame and dishonour might be brought upon a family through involvement in pre-marital sex, adultery, pregnancy out of wedlock, homosexuality and incest (Cetin, 2015; Bhanbhro, 2015; Payton, 2015; Sabbe et al., 2013). In addition, marrying without consent from parents (Sabbe et al., 2013; Gill and Mitra-Kahn, 2012) and marrying outside the clan and/or community (Bhanbhro et al., 2013) can also be considered acts which could bring shame or dishonour to a family, clan or community. Honour and honour killings in Pakistan are under researched, and existing evidence derives largely from human rights and civil society organisations such as the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), Shirkat Gah and the Aurat Foundation. There have been a few small and localised primary research studies conducted in Pakistan such as those of Aase (2002), Shaikh et al. (2010), Bhanbhro et al. (2013) and Shah (2016) but these studies have been limited in respect of the sample.

Author 3 conducted his research between 2011 and 2015 in western Kenya to examine the role of the Catholic Church in the peace-building process following the 2007/08 post-election violence (PEV) in Kakamega County. As a Catholic priest, he was particularly interested in exploring the historical involvement of the Catholic church in peace building prior to the 2007/08 PEV. The church’s peace-building strategies and the challenges faced by the Catholic church in seeking peace and development in the area were all topics of interest to him.

Guided and informed by Emile Durkheim’s (1994) theory of structural functionalism and Galtung et al.’s (2000) theory of structuralism and peace building, author 3 sought to gather views from a wide range of residents in the county in order to evaluate the different functions of the church in the community regarding peace building using mixed-method ethnographic approaches.

The PoR, Kakamega County in western Kenya, experienced significant unrest following the 2007-08 PEV. The area is one of the wealthiest counties in Kenya in terms of natural resources, with fertile agricultural soils, permanent rivers, wetlands and forests (Muchanga, 1998). Yet despite these resources, a government report in 2014 revealed that the region’s economy was under threat and that the county was one of the poorest in Kenya in terms of relative and absolute poverty. Poverty in the county has been attributed to poor leadership, the emigration of able-bodied men to other counties in search of gainful employment, low yields from cash crops, low levels of education and economic inactivity (Aseka, 2014; Miheso, 2014). The area is ethnically diverse and benefits from cultural intermarriage both from within and with the neighbouring border clans in Uganda.

In the following sections, the three authors use narratives from the field to report on their experiences while accessing SSs and how these might have affected the quality of the data obtained.

Methods

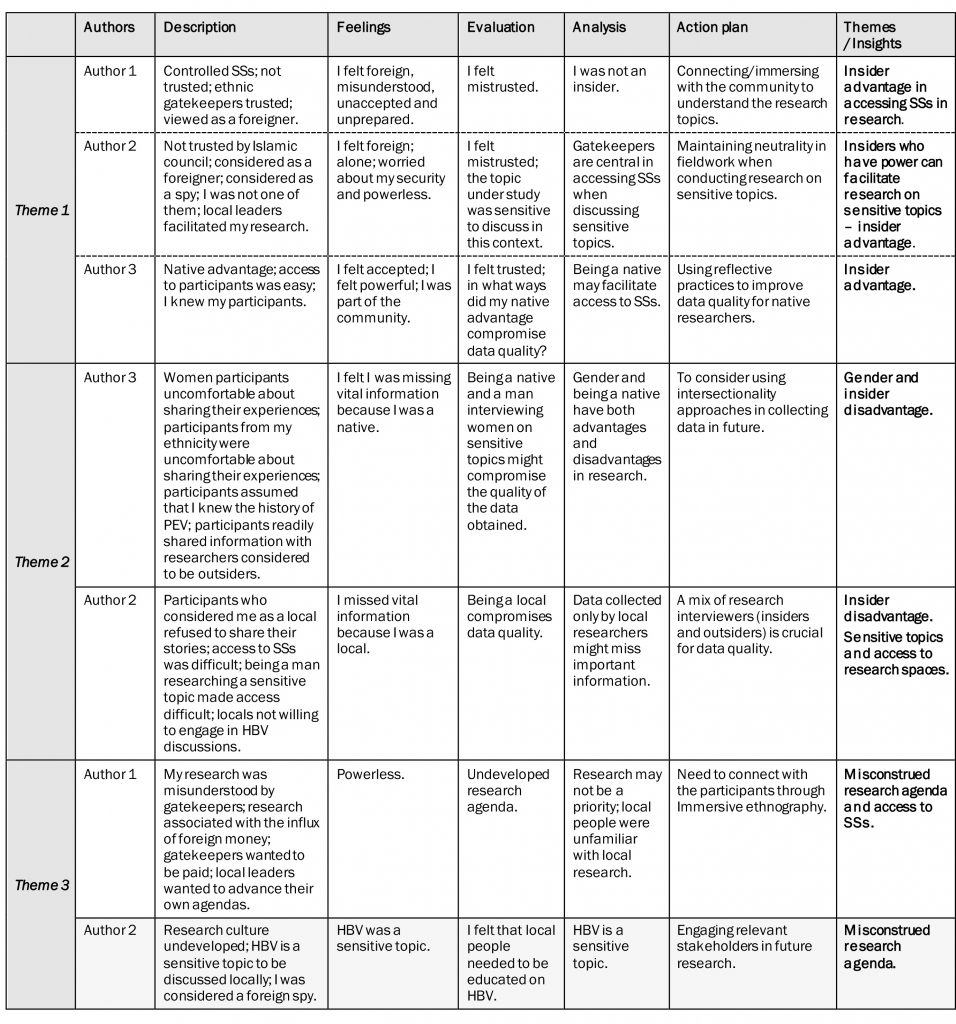

To make sense of their reflective narratives, the authors employed the Gibbs Reflective Cycle (GRC). GRC uses six criteria to assist practitioners to systematically and critically reflect on their experiences in order to be able to make more balanced and precise judgements (Gibbs, 1988). Figure 1 shows that the six stages of analysis entail descriptions of the experience, feelings and thoughts, evaluation of the experience, analysis and action plans. All three authors coded their data using the six criteria separately. Codes which were developed were shared between the authors for review. All three authors reviewed and merged the codes to inform their insights across their experiences.

Insights from the field

Analysis of the reflective narratives from three different research sites delving into different topics using Gibbs’s analysis circle identified three themes relating to positionality and access to SS and PoR:

- Insiders have an advantage in accessing SSs.

- The intersection between gender, insider disadvantage and data quality.

- Context and misconstrued research agenda.

Insider advantage in accessing SSs

The field research experiences of authors 1 and 2 demonstrate the difficulties which native researchers who have lived in developed countries encounter when collecting data in developing countries. Viewed as both natives and foreigners, foreign-educated researchers do not gain automatic access to local study subjects. Author 1 in Kenya and author 2 in Pakistan both found it difficult to establish a working relationship with informants on their research sites, in part because they did not, as outsiders, understand which SSs could acceptably be probed and which could not.

For instance, although author 1 had expected to start gathering information shortly after her arrival in the field, she found it impossible to do so. Social structures were more highly organized than she had thought, and before she began, she needed to gain the trust of locals to help her to build information networks. Her linguistic competence and prior experience of working in city slums, although helpful, did not grant her automatic entry to the slum’s informants in her native land. As she observed:

I quickly realized that each social space has its own private culture, accessible only through the intervention of a trusted intermediary. … I was not immediately welcomed into these controlled social spaces. To an outsider, the slum or rural settlement appears to be homogeneous, but it is in fact a collection of unique social spaces. To gather information from locals, therefore, I had first to master the social norms specific to each space (whether on the street, in school, in sanitation facilities, at water sources, or in informal businesses). In my research area, different people controlled different social spaces. In addition, nine villages in my research area, which was volatile along ethnic lines, were controlled by village watchmen. Upon arriving, I was told by the locals that I could not gather information in the area until I got authorization from the relevant gatekeeper… (Author 1)

Similarly, Author 2, who had lived in the UK for over five years and was a Pakistani with a western education and values, was viewed as a foreigner. While conducting his interviews with the chairperson of the Islamic Council, one of the participants sitting in the room interrupted the discussions on HBV and challenged author 2 for choosing to conduct this research so that he could defame the Pakistani culture to western countries:

… While interviewing the chairman in presence of other audiences, I was surprised when a young man from the audience commented that ‘lagta hey tum foreign agent ho, jo ye masla chuna hey ki bahir Pakistan ko badnaam ker sako’ (‘it looks like you are a foreign agent. That’s why you have chosen this topic [honour killings], to defame Pakistan to foreigners/westerners’). After this encounter, I realised that understanding the social space, and the interviewer’s place in it, is crucial for maintaining the neutrality of the data… (Author 2)

As a researcher returning from the UK to study his own people, these sentiments made author 2 powerless and concerned about his physical security. Author 2 realized the sensitivity of discussing the HBV topic in this context. Sensitive topics such as HBV which are not easily discussed in the public domain can be challenging for researchers considered foreigners yet native. Whereas both author 1 and author 2 encountered difficulties in gaining access to informants and interviewing them in different SSs, author 3 – who had never lived outside his native area – found it relatively easy to recruit and interview study participants. Author 3, a male clergyman and a lecturer at the local university who had lived in the PoR for more than 35 years reported his field work experience as follows:

I am a native of Kakamega county in many ways. I was born, raised and went to school in this area. My parents, siblings, extended family and most of my friends live in the area. I am a senior chaplain at the local university, where I also lecture as well as represent the Christian community on the university senate. Besides this, I am the senior priest of the main Catholic church in Kakamega parish, which also hosts the university and the community in which this research was situated. As such, I enjoy a wide range of social networks in the community, at the university and family. Thus, I have found myself taking a leadership role in the community development projects, bringing warring clans together, counselling and taking advisory roles. These roles and positions have given me multiple identities. … my role in the community and the many advantages I enjoyed gave me a position of power and provided a platform for gaining access to study participants … (Author 3)

Author 3’s account shows the intersection between power and the context in which his research was conducted. He conducted research in a culture which is predominantly patriarchal. Being a man, a catholic priest, educated, a native with a prestigious position on the university senate automatically facilitated his access to research spaces and participants. Unlike authors 1 and 2 who were considered foreigners, author 3 had native advantages.

Intersection between gender, insider disadvantage and data quality

The narratives provided by these three authors indicate that the quality of the data collected in the field in large part depends on the researcher’s ability to negotiate different SSs and to obtain the cooperation of local gatekeepers. By the same token, researchers insufficiently aware of the local context, and their position in it, can compromise study results. Even author 3, a well-accepted ‘insider’, was aware that his position in society hindered many participants from openly discussing their thoughts and views with him. Author 3 further recognized that, when they answered questions about PEV, ethnicity determined how the participants responded. For example, author 3 explained that during the PEV, different ethnic clans fought against each other and when he was interviewing some participants, ethnic affiliations influenced how they shared their views with the interviewers.

Ethnic groups not affiliated with my tribe and women did not feel comfortable discussing issues they felt might offend me – although they comfortably did this with the research assistants… (Author 3)

Author 3 further observed that many informants who knew that he had ministered to victims after the violence believed that he already knew the answers to the questions which he asked:

I was always aware I did not enter the field as an outsider. During data collection, some participants in focus group discussions, for instance, made comments about my role, such as “You must know this better [than I do]” or “As you are aware, violence happened due to ethnic …” My research assistants, by contrast, did not hear the same sentiments from interviewees. (Author 3)

Author 3 also commented on ethical and methodological dilemmas faced by researchers who are themselves insiders:

These differences made me question my involvement in the research – to what extent the data being collected was rigorous enough, or how I was going to de-link from the insider’s position to collect and interpret data without bias. Equally, researching and talking with the clergy and the laity with whom we shared a common bond about our experiences with PEV made me realize how crucial it was to step back and reflect critically on the design of the study to meet the expected academic rigour … (Author 3)

Author 2 similarly received a good reception from people who considered him a foreigner and a bad reception from participants who considered him a native:

Those who considered me as a local did not openly respond to my questions, nor were they willing to share their stories. In part, [this was because] many of the stories of honour killings were already in the local media and they assumed that I was already aware of these; they were reluctant to give insider information. On the other hand, those who identified me as outsider [foreigner] were quite free in sharing their stories and provided detailed answers to my questions. In this way, my perceived position greatly influenced the richness and quality of the data. I later realized that being an insider conversant with the topic, I came off as patronizing to the respondents. This I later confirmed when I listened to a couple of interview recordings, and I made a conscious decision to pretend that I knew nothing about the issue under exploration … (Author 2)

Gender had an effect on how all three researchers accessed SSs and participants. Women participants were unwilling to discuss the effect of PEV on their families with author 3, who was a man. Equally, author 2 was unable to recruit enough female participants for his study. Author 1, who had been introduced to men in the slums to introduce her to different SSs, changed her research approach when she realized that male gatekeepers had ignored her research agenda and that she was running out of time. In the following extract, author 1 provides further insights into how she improvised to overcome the barriers to gathering data which she had encountered in the field:

During the first six weeks, when I visited the slums every day, I had observed many women routinely cleaning the streets, trenches and local schools. These women removed heaps of human and household waste, haphazardly thrown around, from the trenches. Aware that I needed to understand the process by which the streets came to be filled with human and household waste, and why women were the primary cleaners, I decided to break loose from the group of men provided by the local chief to interview the women.

Seeking to be accepted as an insider, I dressed in a local print like those worn by local women rather than jeans. Every day for three weeks, I joined the women cleaning the trenches. Facing an ethical dilemma as to whether I should fully explain my research purpose to them, I decided to tone down my explanation. ‘I am a student,’ I explained, ‘and I am here to see what you are doing and learn from you what women do to help keep their environment sanitary’. [Note: Although they later learned that I was studying at a university abroad, the knowledge did not seem to change their views about me.]

Delightedly welcomed by these women, I joined them in cleaning the streets. The first group introduced me to different groups within the slums, in schools and local churches, and even to some local leaders whom I had not met before. It was from joining and cleaning with women on the streets that I learned about the impact of poor sanitation in the slums such as numerous children dying after falling into pit latrines and deep trenches; girls being raped while accessing toilets at night; incidences of trachoma among children, diarrhoea outbreaks and the use of the of ‘flying toilets’ (Lusambili, 2011).

I was able to glean this treasure-trove of information because I aligned myself with these women within their social space. …this cast doubt on the validity of my initial data and made me question whether information collected from participants who were not slum residents could be incorporated in this research. This experience brought to the fore how important it is to know and verify participants’ social context to avoid falsely skewing the information collected. By immersing myself in the women’s social reality, I also became the ultimate ‘insider’, experiencing for myself what was normative in that context. I was aware that this insider position, coupled with the fact of my being a woman, was going to be a challenge facilitating a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with men, who owned most facilities and were used to receiving tokens from agencies seeking research data. I therefore trained my male research assistant to deal with male FGDs. Although I was present during interviews with male locals, I kept my role passive. (Author 1)

For author 2, being a male researcher had both advantages and disadvantages. For instance, being a man was useful in terms of accessing not only male SSs such as a jirga (a traditional assembly of community male leaders who settle a range of community disputes, and in particular they are held to settle disputes related to honour killings of women and girls) and informal gatherings of villagers in an Otaq (a male guest room).It was also challenging to interview or interact with women in the field, as Author 2 explained:

I managed to interview only two women (both respondents were human rights activists and social workers) by myself; other female interviews were conducted by a female researcher who was hired and trained to undertake interviews on my behalf.

These narratives demonstrate how the intersection between gender, being an insider and social context can influence a researcher’s access and the quality of data obtained.

Context and misconstrued research agenda

Our narratives revealed that research agendas are sometimes misconstrued in both Kenya (see Muia and Oringo, 2016) and in Pakistan (see Zaidi, 2002; PATH, 2015) where the culture needed for social research is not fully supported by the government. Research may not be a priority and for sensitive research topics such as HBV, it can be difficult to recruit and engage the local people. Author 2 found it difficult to gain access to informants on the sensitive topic of HBV:

This research involved a sensitive issue and inviting people to participate in such research is even more difficult, especially by a male researcher from the diaspora. Due to some high-profile honour killings such as the murder of a Pakistani social media celebrity Qandeel Baloch in 2016 by her brother, the issue of honour killings has been contentious and precarious to talk about especially with people coming from abroad. (Author 2)

Similarly, Author 1, conducting research in the Kibera slums, found that some Kenyan locals tended to misconstrue her research agenda. When some locals associated her presence with an influx of money, for instance, some local leaders seeking to advance their own agendas frequently took steps which led to delays:

When I entered the Kibera slums, I had to go to the local chief to get a licence to go into different social spaces, and he provided five men to provide security during my visits. … I was told that my escort would introduce me to different village watchmen, or other leaders who could help me recruit study participants, but when we started mapping where to go in the slums, they hijacked the process and led me to business places and schools that did not meet my study criteria. … on two occasions, the chief’s team went to a restaurant, ordered food, and handed me the bill to pay, putting me in an awkward position. (Author 1)

As in Kenya, author 2, working in Pakistan, found that the culture for social science research was underdeveloped, and the general mistrust of field researchers was detrimental to data collection. Author 2 reports how he was able to leverage his multiple national and cultural identities to help him to overcome these obstacles:

I tried to maintain my position in the field as a native who was in a position of power, from having lived and studied abroad. Unlike the anthropologist Malinowski, who likened himself doing fieldwork to a predator ‘spreading his nets in the right place and waiting for what will fall into them’, I reflected on what I knew about HBV before going in the field. Aware that this background knowledge could affect how I interviewed participants, I made a conscious effort to approach the data collection process as a native, but one who had no knowledge about HBV. (Author 2)

Leaders in the target community also have their own requirements, which did not always accord with the researcher’s views. When seeking access to different SSs to gather information about a sensitive topic, author 2, for instance, faced an ethical dilemma. Of his interview with the chairman of the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII) Pakistan, he reported that:

The Chairman of the CII gave me two conditions for the interview: that the interview would be conducted (1) in presence of other party members (around 20 people sitting on the floor in a circle in the hall); and (2) in the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) office. The JUI is a right-wing political party of which the CII Chairman is one of the leaders.

Although obtaining official permission was a necessary first step, it alone did not immediately open doors to local informants. Although a native Kenyan, author 1 found that because she had lived in the US and ethically, she had to inform her subjects about the foreign university where she was studying, some local people saw her as a foreigner. Social science research, moreover, was regarded as something only foreigners did.

… After obtaining my research permit, I was introduced to the chief by a senior government official. The officials had informed the chief about my research – and in my first meeting with the chief, he had commented that “You are loaded with USA dollars. Big money. People coming to do research here have money and we are in good hands.” … I had not thought of the fact that I would be considered as a foreigner. I considered myself a native … (Author 1)

Author 1 explained the ethical dilemma which arose when she began to recruit informants in the Kibera slums, where some men attempted to push their own agendas:

When I began my research project in the field, the local chief accorded me a group of five men as security to assist in recruiting the participants. Unfamiliar with my research goals and requirements, these men pushed me to recruit people they chose but who did not meet the study criteria. Remembering how Clifford Geertz (1973) emphasized that local behaviours must be understood within their social and cultural contexts, I reflected how it looked for me to visit the slums surrounded by five security guards. Concluding that this would certainly affect the quality of data I could collect, especially from women, I decided not to use them. (Author 1)

As a relatively new researcher conducting her doctoral research, Author 1 discovered how forceful local leaders can be, and how detrimental to the research they can be when trying to use researchers to further their own ends. As noted above, Author 1, as a female researcher, looking into the delicate subject of sanitation faced a number of major obstacles from the outset:

… Despite my repeated reminders that I was there to do research, village elders continued to introduce me as a “donor from America”. The chief started out by mentioning the “big money” my research represented, and from then on, the village elders controlled my position within these social spaces. Mindful of the obvious gender power gap (see Hooks, 2004; Lerner 1986 on patriarchy), I became anxious…

Staff assigned by the chief to assist in organizing separate male and female focus group discussions began by selecting participants for the male focus group. They also diverted these discussions from how the lack of sanitation affected the lives of people living in Kibera to what the government was planning to do for them and how I should help them get funding from abroad. Although the female FGD did discuss some issues related to sanitation, I later learned that all the women who the officials had recruited to take part ran informal businesses in the slums and were connected to the local chief. These FGDs were arranged in controlled spaces such as their business premises, and throughout the process women asked for favours such as money to boost their businesses. (Author 1)

The major barrier for author 2 was his introduction by the gatekeepers to the participants as a researcher who had come from London (not even the UK). Despite repeated requests from the researcher to the gatekeepers that it would be better to introduce him as a local who was studying in the UK, they continued to emphasise that he had come from London:

My gatekeepers were of the view that introducing me as coming from London made a good impression on people and it was easy for them to get together people for interviews and focus groups. One of the implications of this was that people who were running or working in voluntary sector organizations did ask for funding for their organizations.

The narratives reported above show that the research process is still underdeveloped in low-resource settings such as Pakistan and Kenya. When research is misconstrued, access by researchers is contested and data quality can be compromised.

Discussion

In this paper, three researchers’ studying their own communities (Kenya and Pakistan) where the research agenda is not fully developed, presented narratives that demonstrated how positionality and access to the research site could be contested. Although studies have shown that being an insider has the advantage of quick access to the study population, recruitment and trust and of greater understanding (Chavez, 2008; O’Connor, 2004; Rooney, 2005), this may not always be the case. Authors 1 and 2’s shared culture and language with the study participant were presumed to facilitate their access to the study area and recruitment of participants. Nevertheless, these similarities did not seem to influence research process during their fieldwork. The experience of author 1 and 2 highlights practical challenges that authors studying their own communities are likely to face. These experiences also contradicts some of the existing research, which puts emphasis on native advantages in accessing the field and interviewing potential participants (see also Dwyer and Bukle, 2009; Acker, 2000; Narayan, 1993). Author 2’s experience with the Islamic Council of Elders is an illustration of how the dialectic relationships between a researcher and participants can shape the research process (see Narayan, 1999). Being an insider or a foreigner (outsider) affected the data in different ways. For example, author 3’s position as an insider who experienced post-election violence in his diocese made his study participants reluctant to fully narrate their experiences, as they saw no need to re-explain this to someone who sheltered victims of violence in his diocese (Armstrong, 2001; Watson, 1999). While, it is not possible to account for the biasness author 3’s or his participants may have brought to the findings, it is clear that being an insider can compromise the data quality. The challenges faced by author 3 are well documented in literature (see Jacob-Huey, 2002; Narayan, 1993). These scholars posited that balancing the subject and object of research could be an issue of conflicts, as participants tend to ascribe specific roles to researchers. In the same vein, handling emotional issues emanating from participants and familiarity with the study problem can compromise objectivity as well as a researcher’s subjectivity (Garvey, 2014; DeLseyer, 2001; Frank, 2000).

Although studies on positionality have emphasized the importance of researchers positioning themselves before and during the research process (Hall, 1990; Merriam et al., 2010). The findings from the three author’s raises questions as to whether researchers conducting social science research in their own communities should approach fieldwork with a fixed standpoint. As social scientists, we must acknowledge who we are as individuals across socio-cultural and political groups in which we study including the social spaces and the PoR as this is crucial for determining the quality of the data we collect (Freire, 2000; Kezar, 2002). For example, due to the fluidity nature of social science research, there is need to negotiate for legitimacy in the field (Jacob-Hueys, 2002), as illustrated by author 1 experience cleaning the streets with potential study participants or author 2 negotiating legitimacy during his fieldwork on HBV. The fluidity of the research process is well documented in the literature (Bondi, 1990; Jacob-Huey, 2002). Researchers and participants’ subjectivity is not static and there has been a call for researchers to take a more critical, reflective stance in examining the conditions under which they collect their data. Furthermore, researchers come from a variety of disciplines and each discipline has different theoretical underpinnings that inform the research design.

We argue that the main task of conducting fieldwork is to generate knowledge about people and their culture, and this has consequences (Hammersley and Atkinson, 2007). In particular, the consequences are more profound when a researcher misrepresents the study participants, their culture and their stories. For example, Hall (1997) argued that the way people are represented is the way they are treated. Therefore, the process of knowledge production needs to be reflective to the extent that it should encompass explicitly stated and critically reflected assumptions of a researcher, positionality, biases and potential impact on the data and the people. Consequently, researchers find themselves focused on aligning their theoretical perspectives to the study participants rather than being more reflective about the SSs and PoRs and the fact that they may not be compatible with their academic theories (Foucault, 2007).

The authors have discussed two key concepts, i.e. social space (SS) and place of research (PoR) in relations to accessing these spaces and their positionality within them. The micro social spaces within the macro place of research were seen as Bourdieu’s concept of field, according to which are “networks of social relations, structured systems of social positions within which struggles, or maneuvers take place over resources, stakes and access”. In line with this view, the researchers not only acknowledged their influences on the data generated from the social spaces but also were reflexive about their positionality, biases and assumptions.

The researchers attempted to be reflective on key three biases i.e. social, field and intellectualist (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992) during the research process. On the social aspect, author 1 and 2 have acknowledged that they were not aware of the influences and challenges of being insiders but living abroad, but they were conscious of impact on the research and research participants being a man or woman. Second, in the field, this bias appears from the researcher’s position in the academia, either as junior or experienced senior researcher. In this context, the researchers did not have to address such filter, as the research participants did not know the research hierarchy in academia. Third, the intellectualist,- the researcher was mindful of such bias as they were clear in their purpose that they were in the social spaces to collect data and interpret it but not solve the problems faced by the participants in their places of research.

The literature shows that personal, cultural, emotional and political variants can all have an impact on research in one way or another (Al-Natour, 2011). The most frequently discussed idea is the insider/outsider position of a researcher; this dichotomy focuses on the positionality of the researcher and its impact on a research project (Naples, 2003; Coloma, 2008).

Conclusion

In this paper, we have examined our experiences of conducting research in LIMCs with respect to positionality, accessing SSs and PoR. We have shown that being an insider or outsider in SSs and PoR presents multiple identities that can have both advantages and disadvantages with regard to accessing field work and data quality. By using GRC six steps framework to analyse our data, we have delved deeper in our narratives to understand positionality from an intersectional approach. The findings of this paper illustrate that, researchers’ multiple social locations during field work are influenced by different social-cultural categories along lines of gender, place of birth, education, power, status and the participants knowledge and attitudes concerning the type and nature of the research topic. The findings in this paper highlight the ethical dilemma of conducting research in different cultures and provide a platform from which future researchers can learn lessons. The authors have also shown that whereas academic discussions around positionality have in the past focussed on the differences and similarities between the researchers and the researched, in future researchers need to delve deeper by explaining how these differences or similarities affect their findings. This is crucial because, by and large, most ethnographic research findings are usually used for policy, so biased findings can lead to a biased policy formulation. Whether approaching field work as an insider or outsider, we suggest that researchers intending to study communities in their countries of origin must use a reflective framework which can help them to explicitly state and critically reflect their assumptions. Researchers must step back and explain ways in which data collection might have been compromised and/or strengthened by their multiple identities. This self-reflective process would improve the transparency and authenticity of the research processes. Moreover, the research implications of the study relate to the research capacity and cultural competencies building for researchers for taking in account the potential complexities and subtleties of fieldwork and interplay between their positionality and its impact on research processes within a place of research.

Author 1 received ethics approval from the Ministry of Education/Kenya and the American University as part of her doctoral field work.

Author 2 received ethics approval from Sheffield Hallam University, Faculty of Health and Wellbeing Research Ethics Committee.

Author 3 received ethics approval from Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology.

All authors contributed equally to the write up of this article. Conflict of interest: None.

Sadiq Bhanbhro, Montgomery House 32 Collegiate Crescent Sheffield S20 2BP. Email: s.bhanbhro@shu.ac.uk

Aase, T. (2002) The prototypical blood feud: Tangir in the Hindu Kush Mountains. In: Aase, T. (Ed). Tournaments of power: Honour and revenge in the contemporary world. Aldershot: Ashgate, 79-100.

Acker, S. (2000) In/Out/Side: Positioning the researcher in feminist qualitative research. Resources for Feminist research, 28, 1/2, 189.

Alcalde, M. (2007) Going Home: A feminist anthropologist’s reflections on dilemmas of power and positionality in the field. Meridians, 7, 2, 143 -162. CrossRef link

Al-Natour, R. (2011) The Impact of the Researcher on the Researched. M/C Journal, 14, 6. Retrieved from http://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/view/428

Angrosino, M.V. (2005) Recontextualizing observation: Ethnography, pedagogy, and the prospects for a progressive political agenda. In: N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincolln (Eds). The sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage: 729-745.

Apparadurai, A. (1988) Putting hierarchy in its place. Cultural Anthropology, 3, 1, 36-49. CrossRef link

Armstrong, M.S. (2001) Women leaving heterosexuality at mid-life: Transformation in self and relations: Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: York University.

Aseka, C. (2014) Is Kakamega the poorest county in Kenya? The Poverist, [online] 5 December 2014. Available at: http://www.povertist.com/is-kakamega-the-poorest-county-in-kenya/

Bhanbhro, S. (2015) Representation of honour killings: Critical discourse analysis of Pakistani English language newspapers, In: Tomas, J. and Epple, N. (eds), Sexuality, Oppression and Human Rights. Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press: 3-16. CrossRef link

Bhanbhro, S., Wassan, M.R., Shah, M.A., Talpur, A.A. and Wassan, A.A. (2013) Karo-kari – the murder of honour in Sindh Pakistan: An ethnographic study. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 3, 7, 1467-84.

Bondi, L. (1990) Progress in geography and gender: Feminism and difference. Progress in Human Geography, 14, 438-45. CrossRef link

Bourdieu, P. (1990) In Other Words: Essays towards a reflexive sociology: Essays toward a reflexive sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P., and Wacquant, L. J. D. (Eds.). (1992) An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bourke, B. (2014) Positionality: Reflecting on the research process. The qualitative report, 19, 33, 1-9.

Brosnan, C. (2010) Making sense of differences between medical schools through Bourdieu’s concept of ‘field’. Medical education, 44, 7, 645-652. CrossRef link

Campbell, J. (1964) Honour, family, and patronage: A study of institutions and moral values in a Greek mountain community. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cetin, I. (2015) Defining recent femicide in modern Turkey: Revolt killing. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 16, 2, 346-60.

Chavez, C. (2008) Conceptualizing from the inside: Advantages, complications, and demands on insider positionality. The Qualitative Report, 13, 3, 474-494.

Coghlan, D., and Brydon-Miller, M. (Eds.) (2014) The SAGE encyclopaedia of action research. London: Sage. CrossRef link

Coloma, R. (2008) Border crossing subjectivities and research: Through the prism of feminists of colour. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 11, 1, 11-27. CrossRef link

DeLyser, D. (2001) Do you really live here? Thoughts on insider researcher. Geographical Review, 9, 1, 441-453. CrossRef link

Durkheim, É. (1994) Social facts. In: Martin, M, McIntyre, L C (eds). Readings in the Philosophy of Social Science. Boston: MIT Press, 433–440.

Dwyer, S.C. and Buckle, J. (2009) The Space Between: on being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8, 1, 54-63. CrossRef link

England, K.V.L. (1994) Getting personal: Reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. The Professional Geographer, 46, 1, 80-9. CrossRef link

Farmer, P.E., Furin J.J. and Katz, J.T. (2004) Global health equity. Lancet, 29, 363, 1832. CrossRef link

Farmer, P. (2005) Pathologies of power: Health, human rights, and the new war on the poor. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press.

Fay, B. (1996) Contemporary philosophy of social science: A multicultural approach. Cambridge, UK: Blackwell.

Foucault, M. (2007) What is Critique? In: Lotringer, S. and Hochroth L. (eds). The Politics of Truth. Los Angeles: Semiotext (e).

Frank, A. W. (2000) The standpoint of the storyteller. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 3, 354-365. CrossRef link

Freire, P. (2000) Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum.

Galtung J., Jacobsen, C.G. and Brand-Jacobsen, K.F. (2000) Searching for peace: The road to transcend. London: Pluto Press.

Garvey, R. (2014) Professor of business Education. York St John University. (Personal communication, 29 April 2014).

Geertz, C. (1973) The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford: Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic.

Gill, A. and Mitra-Kahn, T. (2012) Modernising the other: Assessing the ideological underpinnings of the policy discourse on forced marriage in the UK. Policy and Politics, 40, 1, 107-22. CrossRef link

Government of Kenya (2000) Economic Survey, Nairobi. GOK Publication.

Hall, S. (1990) Cultural identity and diaspora. In: Rutherford, J (ed.) Identity: Community, culture, difference. London: Lawrence & Wisbart: pp. 222-237.

Hall, S. (1997) Introduction. In: Hall, S. (Ed.), Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. London: Sage in association with the Open University.

Hammersley, M., and Atkinson, P. (2007) Ethnography: Principles in practice (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. CrossRef link

Hester, M., Gangoli, G., Gill, A., Mulvihill, N., Bates, L., Matolcsi, A., Walker, S. J., and Yar, K. (2015) Victim/survivor voices – a participatory research project. London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC). Retrieved from https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/university-of-bristol-hbv-study.pdf

Hooks, B. (2004) The will to change: Men, masculinity, and love. New York: Atria Books.

Huisman, K. (2008) “Does this mean you’re not going to come visit me anymore?”: An inquiry into an ethics of reciprocity and positionality in feminist ethnographic research. Sociological Inquiry, 78, 3, 372–396. CrossRef link

Hunnicutt, G. (2009) Varieties of patriarchy and violence against women: Resurrecting “patriarchy” as a theoretical tool. Violence Against Women, 15, 5, 553-573. CrossRef link

Iranian and Kurdish Women’s Rights Organisation (2014) Postcode lottery: police recording of reported ‘honour’ based violence. Iranian and Kurdish Women’s Rights Organisation. Available at: http://ikwro.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2014/02/HBV-FOI-report-Post-code-lottery-04.02.2014-Final.pdf. [Accessed: 01/10/2016].

Jacobs-Huey, L. (2002) The natives are gazing and talking back: Reviewing the problematics of positionality, voice, and accountability among “Native” anthropologists. American Anthropologist, 104, 3, 791-804. CrossRef link

Kezar, A. (2002) Reconstructing static images of leadership: An application of positionality theory. Journal of Leadership Studies, 8, 3, 94-109. CrossRef link

Lerner, G. (1986) The creation of patriarchy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lusambili, A. (2008) Environmental sanitation and gender among the urban poor: A case study of the Kibera slums, Kenya. Berlin: VDM Verlag Dr. Muller.

Lusambili, A. (2011) It is our dirty little secret: An ethnographic study of the flying toilets in Kibera Slums, Nairobi. STEPS Working Paper 44. Brighton: STEPS Centre. Available at: https://steps-centre.org/publication/it-is-our-dirty-little-secret-an-ethnographic-study-of-the-flying-toilets-in-kibera-slums-nairobi/ [Accessed: 09/05/2018].

Merriam, S. B., Johnson-Bailey, J., Lee, M., Kee, Y., Ntseane, G. and Muhamad, M. (2010) Power and positionality: negotiating insider/outsider status within and across cultures. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 20, 5, 405-416. CrossRef link

Miheso, W. (2014) Factors making Kakamega the poorest in Kenya. The Poverist, [online], 7 December 2014. Available at: www.povertist.com/factors-making-kakamega-the-poorest-county-in-kenya/ [Accessed: 18/11/2016].

Minkler, M., Wallace S. P. and McDonald, M. (1994) The political economy of health: A useful theoretical tool for health education practice. Int Q Community Health Educ, 15, 2, 111-26. CrossRef link

Muchanga, K. L. (1998) Impact of economic activities on the ecology of Isukha and Idakho areas of Western Kenya c.1850-1945. MA thesis, Kenyatta University. Nairobi.

Muia, A., M., and Oringo, J.O (2016) Constraints on research productivity in Kenyan universities: Case study of university of Nairobi, Kenya. International Journal of Recent Advances in Multidisciplinary Research, 3, 8, 1785-1794.

Naples, N. A. (2003) Feminism and method: ethnography, discourse analysis, and activist research. New York: Routledge.

Narayan, K. (1993) How native is a ‘native’ anthropologist? American Anthropologist, 95, 3, 671-86. CrossRef link

Nation Newspaper (2014) Kakamega poverty devolution ministry report. Nation Newspaper Available at: https://www.nation.co.ke/counties/Kakamega-Poverty-Devolution-Ministry-Report/1107872-2517956-30hd8t/index.html [Accessed: 10/11/2016].

Nesheiwat, F. (2005) Honour crimes in Jordan: Their treatment under Islamic and Jordanian criminal laws. Penn State International Law Review, 23, 251–281.

O’Connor, P. (2004) The conditionality of status: Experience based reflections on the insider/outsider issue. Australian Geographer, 35, 2, 169-176. CrossRef link

PATH (2015) Research and development for health in Kenya: Landscape analysis executive summary. Washington, USA: PATH. Available at: https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/APP_kenya_rd_landscape_exec_summaryr1.pdf [Accessed: 03/06/2019].

Payton, J. (2015). For the boys in the family: An investigation into the relationship between ‘honour’-based violence and endogamy. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32, 9, 1-26. CrossRef link

Peristiany, J. G. (eds) (1965) Honour and shame: the values of Mediterranean society. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Peters, K. (1998) Community-based waste management for environmental management and income generation in low-income areas: A case study of Nairobi, Kenya. Canada’s Office of Urban Agriculture: City Farmer Press.

Pitt-Rivers, J. A. (1965) Honour and social status. In: Peristiany, J. G. (eds.) Honour and shame: the values of Mediterranean society. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Rice, T. (1998) The Economics of health reconsidered. Chicago: Health Administration Press.

Rooney, P. (2005) Researching from the inside-does it compromise validity? A discussion Level, 3, 3, 1-19.

Sabbe, A., Oulami, H., Zekraouni, W., Hikmat, H., Temmerman, M. and Leye, E. (2013) Determinants of child and forced marriage in Morocco: Stakeholder perspectives on health, policies and human rights. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 13, 43, 1-12. CrossRef link

Shah, N. (2016) Honour and Violence: Gender, power and law in Southern Pakistan. Oxford: Berghahn Books. CrossRef link

Shaikh, M. A., Shaikh, I. A., Kamal, A., and Masood, S. (2010) Attitudes about honour killing among men and women – perspective from Islamabad. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, 22, 3, 38-41.

Shutt, R. (1998) The trouble with capitalism: An enquiry into the causes of global economic failure. London and New York: Zed Books.

Stiglitz, J. (2002) Globalisation and its discontents. London: Penguin Books.

Swartz, D.L. (2016) Bourdieu’s Concept of Field. Obo in Sociology. CrossRef link

Thompson, J., Porras, I.T. and Tumwine, J.K. (2001) Drawers of water II: 30 years of change in domestic water use and environmental health in East Africa. London: International Institute for Environment and Development. Available at: http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/9049IIED.pdf [Accessed: 09/05/2018].

True, J. (2012) Political economy of violence against women. Oxford: Oxford University Press. CrossRef link

Watson, K.D. (1999) “The way I research is who I am”, The subjective experience of qualitative researchers. Unpublished masters thesis. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: York University.

World Bank (2004) Rogues no more? Water kiosk operators achieve credibility in Kibera (English). Water and sanitation program field note. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/990461468590490933/Rogues-no-more-Water-kiosk-operators-achieve-credibility-in-Kibera [Accessed 09/05/2018].

World Bank (2005) Understanding small scale providers of sanitation services: A case study of Kibera (English). Water supply and sanitation program field note. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/356591468429540855/Understanding-small-scale-providers-of-sanitation-services-a-case-study-of-Kibera [Accessed: 09/05/2018].

Zaidi, A. (2002) Dismal State of Social Sciences in Pakistan. Economic and Political Weekly, 37, 35, 3644-661.