Abstract

Outsider (mis)representations of Gypsies, Travellers or Roma, especially in populist newsprint and other media are analysed. Given the crisis in newspaper sales, there is greater incentive to create alarmist headlines and melodrama to enhance visibility and increase circulation. Traditionally valued in-depth journalism presupposes detailed enquiry, direct experience and face-to-face questioning. Ideally, the investigative journalist should not uncritically recycle hackneyed clichés. Yet pre-judgement dominates populist news coverage of Gypsies, Travellers and Roma. Centuries’ old stereotypes are recycled with minimum legal protection for the demonised minority.

The exotic and macabre are regularly associated with nomadic peoples: perceived as evading hegemonic control. In contrast to other minorities, there is minimum tradition of ‘The book’ as ethnic testimony, encouraging literate skills in all domains. These are elaborated for knowledge access and survival alongside the dominant society. Such groups refine professional legal and political strategies creating specific niches and with expertise to challenge racism. By contrast, nomads have tended to use movement and invisibility for political/economic survival. Evasion and unpredictability have hitherto been creative, productive strategies.

Select examples reveal continuing stereotypes and imagined practices projected onto Gypsies, Travellers and Roma, too often revealing minimal or indeed no contact with the peoples portrayed. Constructed examples include assertions that: Gypsies steal babies, are work-shy, and remain locked in some primitivised past, while feared as menacing invaders of others’ territory. Such media-enhanced examples are ripe for unravelling and problematisation, thanks to the anthropologist author’s extensive fieldwork, living among Gypsies, long-term ethnographic knowledge and research. Contradictions are exposed. There are contrasts between non-Gypsy hegemonic misrepresentations, indeed inventions, and the Gypsies’ own practices, their alternative values and positionality. Analysis is enhanced by an examination of the wider hegemonic context and changing or continuous anti-Gypsy political agendas.

Media, Non-literacy and Vulnerability

This article examines outsider (mis)representations of Gypsies, Travellers or Roma within the media, especially in populist newsprint. Given the crisis in newspaper sales, there is greater incentive to create alarmist headlines and melodrama to enhance visibility and circulation. Traditionally valued in-depth journalism presupposes detailed enquiry, direct experience and face-to-face questioning, bearing some initial similarities with anthropological fieldwork. Ideally the investigative journalist should not uncritically recycle taken-for-granted, hackneyed clichés. The very meaning of prejudice is now dulled, obliterating the original act of advance judgement. Yet ill informed pre-judgement dominates outsider populist news coverage of Gypsies, Travellers and Roma. Centuries’ old stereotypes are recycled unchallenged.

The exotic and macabre are regularly associated with nomadic peoples: perceived as dangerous strangers. They are threatening when perceived as evading hegemonic control. In contrast to other minorities, there is minimum tradition of a ‘Holy Book’ as ethnic testimony, encouraging literacy in all domains. Elsewhere, literate skills are elaborated for knowledge access and survival alongside, indeed embedded within, the outsider majority.

Such groups, with traditionally integrated literacy, can choose to enter key professions, such as law or medicine, with specific niches publicly respected by the dominant society. Niche occupants access the intimate workings of state hegemony. With this knowledge, politico/legal strategies can be devised which protect the outsider minority. Here, with publicly valued and official profiles, such minority representatives acquire the expertise, on the dominant society’s own terms, to challenge racism and exclusion.

Nomadic Outsiders and Enforced Settlement

In contrast to minority niches exploiting educational integration, nomads have tended to use movement and invisibility for political/economic survival in the midst of a sedentarist polity. Evasion and unpredictability have hitherto been creative, productive strategies. Nevertheless, Gypsies have also had to know the dominant outsider when practicing their own economic niches, at least in the UK. Elsewhere, I elaborate the Gypsies’ unique form of nomadism, ignored in classical anthropological studies which highlighted only hunter-gatherers and pastoralists (Okely, 1983). Already in the 1950s, Rena Cotton, the anthropologist using the term Gypsiology with respect (1954, 1955), highlighted a different nomad. Gypsies were subsequently labelled ‘Service Nomads’, alongside others.

Just as lawyers and doctors from ethnic minorities have had to be familiar with the dominant society, so have Gypsies, but differently. They have sought gaps in the economy for the occasional supply of goods and services. They have exploited their exoticised image to become skilled fortune-tellers, de facto psychotherapists (Okely, 1996: ch. 5).

Given their multi-occupations, a mono identity is rarely maintained when inter-relating with non-Gypsy society. Moreover, the exotic image of fortune-teller is vulnerable to demonization. Other roles may entail hiding ethnicity, e.g. as antique dealer (Okely, 1996: chs 3 and 5).1 During the 197Os and some subsequent years in England, literacy was rarely essential for the variegated, innovative skills among English Gypsies and Irish Travellers. The Gypsies were educated in their own cultural knowledge, not ‘schooled’ for assimilation (Okely, 1997).

In contrast to Northern European groups above, Roma/Gypsy peoples from former communist Eastern/Central Europe have experienced decades of enforced settlement, thanks to brutal regimes. Today, many have internalised a hegemonic hatred of nomadism, thereby obliterating their history. Economic roles and stigmas have turned upside down. Under communism, Hungarian Gypsies were forbidden to work as self-employed but obliged to labour in factories (Stewart, 1997). Kaminski revealed how Gypsies in communist Poland and Slovakia operated as secret traders of consumer goods, risking stigmatisation as ‘enemy’ capitalists (1980).

Since the collapse of communism and state subsidised industries, Roma or Gypsies were invariably the first to be sacked. Simultaneously, their former stigmatised economic activities as mini-capitalists were suddenly legitimised, but appropriated by non-Gypsies. Again, the Gypsies were marginalised, although for the opposite reasons. While a few became enriched by selling scrap metal from derelict factories many, perhaps the majority, were abandoned in extreme poverty (Ries, 2007). Racist views re-emerged with a vengeance. No wonder that Roma or Gypsies from former communist Europe have migrated to Northern Europe. Inevitably, the opening of EU borders to persons from Bulgaria and Romania further fuelled the media panic.

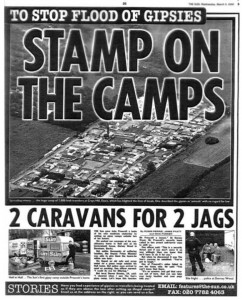

Paradoxically, the English Gypsies documented by Okely (1975, 1983) and Acton (1973), mainly semi-nomadic and useful to capitalism, have in turn become victims of enforced settlement (Smith and Greenfields, 2013). This followed the 1994 abolition of government duty to provide Gypsy sites. Steered through parliament by future Conservative leader, Michael Howard, it decreed that Gypsies should henceforth purchase their own land. Predictably, this proved near impossible. Over 95 per cent of site applications by Gypsies were refused planning permission. The Sun newspaper produced the outrageous headline: ‘Stamp on the Camps’ (see Figure 1).

Anthropology’s Ethnographic Methods

In the light of the political, economic overview above, this article focuses on the consequences for media coverage. Contrasts or continuities in stereotypes and imagined practices projected onto Gypsies, Travellers and Roma, are presented with examples. Such stereotypes reveal minimal or indeed no contact with the peoples portrayed. Instead, the received ‘wisdom’ offers ample potential for alarmist representation. The latest high-speed internet ensures immediate global transmission for unchallenged projection.

The news media reveals very specific examples, consistent with centuries old, outsider constructions. The most prominent in recent assertions include the following: Gypsies are either work shy or wealthy tax avoiders, Gypsies steal babies, Gypsies remain in some primitivised past, while feared as menacing invaders. Media-enhanced misrepresentations are ripe for unravelling, not in terms of specialist media theories, but instead in the light of relevant anthropological literature. This is enhanced by awareness of historical texts, including the work of Gypsiologists.2

The insights from social anthropology draw upon long-term participant observation, ideally co-residence for a year or more. The anthropologist derives specific authority from individual fieldwork (Okely, 2012). In this case, the author’s in-depth experience entailed living among the Gypsies on several encampments from the 1970s, in addition to follow-up visits amounting to over two years (see Figure 2, the first site where Okely lived).

In contrast to some social sciences and linguistics, the research does not depend on data gathering by subordinate assistants under a managerial master who publishes all under his/her one name. The tradition of intensive fieldwork, where the author is both researcher and writer, goes back to the early 20th century with the pioneering Malinowski and Chicago School of Sociology. The latter introduced the term ‘participant observation’. Lived fieldwork provides unique ethnographic knowledge.

Anthropological practice depends on one person as participant observer, note-taker, analyst and author. Since evidence is passed through the one authority, readers from other disciplines may misinterpret the emergent texts as ‘merely personal’. Given that fieldwork is no group exercise, the word ‘I’ frequently appears in the text. Authority indeed rests on individual testimony and experience. The use of ‘I’ has been extensively debated (Clifford and Marcus, 1986). It reminds the reader that ‘the anthropologist was there’, not the reader.

Once considered narcissism to confront the consequences of the fieldworker’s gender, age, ethnicity and personality in gaining access and trust, discussions of the fieldworker’s autobiography as positionality, (Okely and Callaway, 1992), are now taken for granted. Some anthropologists may be accompanied by partner and offspring (Okely, 2012: Ch. 7). The methodological challenges of becoming integrated as outsider among Gypsies were outlined in The Traveller-Gypsies (Okely, 1983: Ch. 3), despite the fact that Okely’s doctoral supervisor, Godfrey Lienhardt, suggested its relegation to an appendix.

Contrary to caricatures, social anthropology does not rest on the study of a people as isolate, divorced from wider history and polity. This anthropologist’s research included intensive studies of localities beyond encampments, including participant observation among council officials, local house-dwellers and law courts. It extended to the collection and interpretation of local newspapers’ coverage of Gypsies and/or Travellers.

Regrettably, a hegemony of quantitative methods risks undermining the qualitative and unique scientific knowledge which emerges (Okely, 1996). Ethnography is a method in its own right emerging from days, weeks, months, sometimes years. The anthropologist is not only co-resident, but may work with the people, attend gatherings and witness the joy and grief of lived events. Often key insights occur during shared activity and experiences (Okely, 1987, 1996: Ch. 1). The now trusted person listens to narratives in context, not in response to formal interviews, let alone clipboard questionnaires administered by strangers in a one-off encounter. Some social scientists and quantitative researchers in other disciplines still trot out the cliché that such research is ‘only anecdotal’. A century or more of research is thus inappropriately demonised and arrogantly ignored.

By contrast, the anecdote may throw light on an entire pattern of behaviour and set of beliefs. This I documented (Okely, 1994), where just one stray footnote by Thompson (1922) recording an anecdote helped explain the system of Gypsy pollution beliefs (Okely, 1983: Ch. 6). Extracts of Okely’s article were reprinted in an Open University methods textbook (Yates, 2004). Student readers were asked to follow her process of discovery, paying special attention to the footnote, which others might have dismissed as mere anecdote. Eureka moments of discovery, while valued in orthodox science, risk being rejected by positivists who retain a fantasy of ‘hard science.’

Professor Stephen Rose, fully qualified in both ‘hard science’ and sociology, has critically problematised what other disciplines call ‘physics envy’ (Okely, 2012: 7-9). Social sciences and other disciplines, including biology, cannot be judged by the same criteria as physics. Okely’s Anthropological Practice: fieldwork and the ethnographic method (2012) reveals that pioneer European fieldworkers, researching in New Guinea, were often trained biologists before becoming social anthropologists. They studied animals or flora in the total context and became more fascinated by the local humans. Eventually they preferred not to extract individuals in one to one interrogations. Emergent anthropologists moved from interviewing via an interpreter, to shared living with unfolding events, narratives and indeed ‘the anecdote’ (ibid. p.18-19).

Granted, there are key demands for quantitative based research. But vital research may emerge only from in depth ethnography where the anthropologist discovers the total system. This may contradict positivist, depersonalised mass surveys, as Edmund Leach (1967) has convincingly argued (Okely, 2012: 13).

Media Madness needs and finds its financial Scapegoat

Contradictions can be exposed in news cuttings on Gypsies, Travellers or Roma. There are contrasts between gorgio (non-Gypsy) hegemonic misrepresentations, indeed inventions, and the Gypsies’ own practices, alternative values and positionality. Analysis is enhanced by an examination of the wider hegemonic context and changing anti-Gypsy political agendas. So-called journalists have succeeded in ‘shock and awe’ against all reasoning. In the 1970s, the Gypsies were mainly non-literate, so saved from full tabloid terror, although today’s headlines and melodramas are more inflated. With visual and other media acceleration, the competition between declining newsprints is ever desperate. In those days, many Gypsies had generator-charged televisions. Word went round the camp if a Gypsy featured.

Today, the media’s ‘Breaking news’ draws in the audience only for a while. Soon the public needs another ‘moral panic’ (McLuhan, 1964). The Gypsies, with centuries of demonization, have become the ideal scapegoat for new uncertainties. With economic downturn, political instability and massive job losses, increasing divisions of wealth and poverty, there is comfort in blaming strangers, seemingly stealing from ‘us’. Simon Jenkins asserts: ‘Everyone is on the take, and whole industries are on white-collar subsidies. Some of us are just much smarter at concealing it’ (2014).

A television series has been used to demonise Gypsies in new ways. When the dreaded Big Fat Gypsy Wedding Channel 4 (2011) series was showing, I was deluged with comments from people who hitherto rarely watched populist programmes. The daughter of an Oxford philosophy Don and beneficiary of an elite public school and university degree, launched into a deluge of anti-Gypsyism. People, who have never knowingly met a Gypsy, are compelled to give me supposed truths (Okely, 2008). The anthropologist becomes the psychotherapist onto whom all fantasies are projected.

In her parental North Oxford house, this usually intelligent young woman declared: ‘Gypsies! They don’t pay taxes!’ Through the kitchen window, was visible a neighbour’s elegant house. Once his permanent abode, it is now inhabited only a few months of the year. Its owner alternates between his other properties around Europe. Once a humble schoolteacher, after patenting an IT system he sold it to state institutions, especially schools. Thanks to massive taxpayers’ public funding, this man is a multi-millionaire. Despite homes in Oxford and elsewhere, his official permanent residence, (for tax avoidance), is a mere garage in the British outpost of Gibraltar. Thus a neighbour’s tax avoidance passes unremarked, while unknown Gypsies are criminalised by media hearsay.

Primitivism

The Channel 4 BFG series inspired Gypsy and Traveller protests outside the London studio. Subsequently, the company was prosecuted for giant posters of a young boy with the title across his image. As feared, Gypsy children were bullied at school. In 2012 the chief creative officer was ‘rapped’ by the Advertising Standards Authority for endorsing “negative stereotypes” (The Independent, 2014: 46). Already the producers, in defence of some of the Gypsy protests outside the studio, declared their filming was merely ‘observational’. They had misleadingly appropriated the anthropological concept of ‘observational filming’ which classically excludes a voice-over (Crawford and Turton, 1992). Instead, total space is given to the voices of the subjects. The participants’ own dialogues, with subtitles, if not English, are the major source of understanding. The priority was to ‘show’, never to ‘tell’ the viewer how to interpret. No one in the media had the curiosity to point out the flagrant subversion of the format. Instead, every opening scene depended on an invisible outsider, the actress Barbara Flynn, who guided viewers’ perception of the already deceptive and voyeuristic editing.

Most inspiring as response, was a morning TV programme where two women, one an English Gypsy and the other an Irish Traveller, were invited to discuss the series. The populist male journalists repeated the ‘observational’ defence, but showed increasing astonishment as they woke up to the brilliant, articulate comments by the two women. In response to another defence as being merely a ‘documentary’, the Gypsy woman replied: ‘It’s not a documentary. It’s a mockumentary’. The journalists were speechless. Against their lazy prejudices, they were confronted by disturbing evidence that Traveller/Gypsy women were superbly intelligent and articulate.

Child Theft

An emergent melodramatic theme in the news media include the centuries’ old belief in child theft by Gypsies, something of which Jews were also once accused (Doughty, 2013). But, given the latter’s relative political integration and Holocaust recognition in the public domain, such racist projections have long disintegrated. In 2013 the alleged theft by dark skinned, dark eyed Greek Roma Gypsies of the blonde blue-eyed, Greek ‘Angel’ Maria created a media storm throughout Europe. A US anthropologist emailed me revealing the news had crossed the Atlantic.

Maria was taken into custody and a photograph, taken presumably by her custodians, shows her weeping and contrasting with the happy images later released by the family. The melodrama spread from Greece to Ireland. The Daily Mirror’s front-page headlines declared:

Abduction panic moves closer

SECOND BLONDE GIRL FOUND LIVING WITH GYPSIES

(23 October 2013)

Someone reported ‘stolen’ fair skinned children with two Roma families who had lived in Dublin and the Irish Midlands for several years. Without further ado, these children were taken into ‘custody’ by the police, i.e. snatched from their parents, for at least one night to an alien place. Subsequent DNA tests proved the children were the offspring of their Roma parents. They were eventually returned (The Guardian, 2013: 32).

Here indeed there is a case of kidnapping, however, not by Gypsies but by non-Gypsy State officials. Finally, Ireland’s justice minister gave the children’s ombudsman special powers to investigate the behaviour of the garda who took into custody blonde children of two Roma couples (The Guardian, 2013: 32). All this is a dark echo of the nursery rhyme:

My Mother said, I never should

Play with the gypsies in the wood.

If I did, she would say;

‘Naughty girl to disobey!

Your hair shan’t curl and your shoes shan’t shine,

You gypsy girl, you shan’t be mine!

The opening lines were repeated in an online image of the social father and mother of the blonde, blue-eyed ‘stolen’ child in Greece. Being darker in skin, it was presumed the girl had come from Northern European, Anglo-Saxon parents, and had certainly been “stolen”. Soon it emerged that the biological parents were Romanian Roma who, after visiting Greece for seasonal farm work, had given the child to Greek Roma parents. The biological parents, dark-skinned with brown eyes, had additional fair haired, pale skin, almost albino children (Daily Mirror, 2013; Daily Mail, 2013). This was a genetic pattern. The Romanian parents had hoped for a better life for Maria, given their own large family and extreme poverty. A small amount of money was given to the adoptive parents. This was exploited by the media as proof of sale. The scandal changed from theft to sale, even though it also emerged that official adoption procedures in Greece were deregulated. The Guardian headlines joined in:

‘Greek child trafficking exposed as Maria’s mother found and more couples charged’

(26 October 2013)

The ensuing texts were more balanced (Doughty, 2013).

Given the media’s obsessive need for demonized marginals, no possible comparisons would be made with celebrities who pay thousands to strangers for renting their wombs. ‘Buying’ and ‘selling’ babies is acceptable for the mainstream but falsely attributed to Gypsies. The Maria myth became an excuse for linking up with the vanished English Madeleine McCann in Portugal (Doughty, 2013). Despite the ultimate discrediting of the myth, The Daily Express, on its front page within months alerted its readers:

‘MADELEINE. POLICE PROBE 2 TRAVELLER CAMPSITES’

(February 4 2014)

Official Theft of Gypsy Children

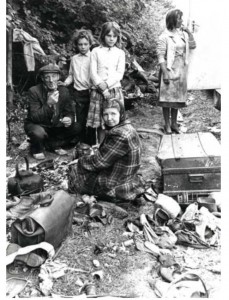

The 1967 Ministry Gypsy Census report privileged children on the photomontage cover (see Figure 3). The implicit message is, even if you dislike these people, at least take pity on the innocent children who do not choose their parentage. When my Gypsy neighbours saw it, several were indignant at an image which emphasized the children’s grubbiness, and with one apparently scratching himself.

The myth of Gypsy theft of children is so ingrained in western hegemony that, not surprisingly, there were resonances during my fieldwork in Southern England, decades ago. One day, several policemen invaded our site, brandishing a photograph of a baby. They were clearly embarrassed, but had been ordered by their superior to search the Gypsy camp for a stolen baby. The latter had disappeared from a pram outside a shop. The Gypsies were very diplomatic to the awkward officers. Their social skills in dealing with officials were impressive. They said what a terrible thing. They would certainly look out for the baby and inform the authorities.

I had, by then, learned from a previous confrontation with the police that it was best to behave with deference, never defiance as when a CND student protester (Okely, 1983: 42-43). But on a Gypsy site, my recovered middle class accent calmed my interrogator. The police did not search our caravans and left. Later, it was found that a mentally deranged house-dweller, having no links with Gypsies, had snatched the baby. Predictably, the police were never ordered to invade and interrogate the local housed community.

The belief in Gypsy child theft has a painful inversion, based on empirical evidence concerning the dominant society’s institutionalized practice. Gradually, I discovered the Gypsies lived with a perpetual fear of child appropriation by gorgios (non-Gypsies). Seemingly unscientific anecdotes or examples have ensured the hitherto hidden Gypsy perspective.

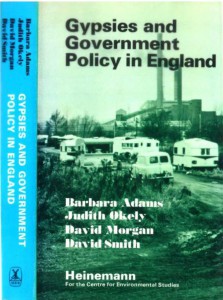

In the 1970s there were still the occasional families who, having abandoned a horse drawn wagon, could not upgrade to a motor vehicle, so lived in tents (see Figure 4). One family walked through several counties, all possessions on a knife-grinding cart (Okely, 1983: 147). One Gypsy woman, who lived in a tent with her family (see also image Okely, 1992: 18), described how a gorgio man accosted her. Her husband was out working. This stranger insisted on inspecting the tent. He declared she could have her children taken away if she did not let him. I naively asked why she was so compliant and what proof she had of his authority. She said it was always best not to resist. The man examined the tent and departed, never to reappear.

The fear of child theft by outsiders was deeply ingrained among the Gypsy children. One evening, I was asked to babysit in a neighbours’ caravan. As was customary, the eldest girl, no more than seven, acted the mother to her younger sister. Tucking her up in bed, she whispered: ‘Its alright, you’re safe here. There’s no gavvers (police), no education officers outside looking to take you away. Go to sleep, me darlin’.

Children were always told to watch out for the “devil” roaming outside the camp. The devil was specifically identified as ‘A man with a brief case’. This, for a largely non-literate community, was the mark of an official. Among the local newspaper photo archives was one clearly taken in the presence of an official (see Figure 5). In the foreground is a briefcase, doubtless owned by a facilitating official. Seemingly the outsider photographer intended to emphasise the external clutter in which the family lived. But the Gypsy boy’s gaze directed at the briefcase tells the anthropologist that behind the camera is a ‘devil’ abductor.

Child theft was not only imagined, but something done with full force of the non-Gypsy law. In contrast to the media enhanced myths of Gypsies stealing children, there is extensive historical evidence of the dominant society’s forceable institutionalization of Gypsy or Roma children, for example in Finland (pc. A.M. Viljan, 2013) and the Pro Juventute policy in Switzerland (Okely, 1997: 73-74; Doughty, 2013). A member of the English Gypsy Council was taken into care. He returned to his people as soon as he reached the age of independence.

The film and book Philomena (Sixsmith, 2009) exposes the institutionalized ‘selling’ of Irish ‘illegitimate’ children for adoption. All this was against the wishes of the teenage mothers who were incarcerated and exploited as near slaves in laundries run by nuns. Similarly, many British children were sent to Australia, having been told wrongly they were orphans, where some were exploited as child labour and sexually abused (Humphreys, 1996). Again, only recently has this been confronted and elicited apologies. There are ever more examples emerging of state instituted seizure of children for ulterior purposes. But the myth of child theft by Gypsies continues, ever enhanced by media inventions.

EU Accession: Migrants not Nomads

Another media panic is migration as invasion, and specifically that of Roma. This coincided with the loosening of the EU borders for Bulgarians and Romanians. As outlined above, the Roma of Central and Eastern Europe were forcibly settled under communism or long before, exploited as slaves. In 2000, fellow anthropologist Marek Kaminski and I visited the Roma museum near Krakow. Here was fully documented the compulsory seizure of Polish Gypsy horses and wagons. Just one wagon was left as ‘authentic’ exhibit in the yard. Bleak photos documented the Gypsies’ incarceration in high-rise concrete flats. All this in the iconic year of 1968 when Paris and beyond, were undergoing a very different revolution in Western and Northern Europe. While Eastern Europe was re-enslaving nomads, enforcing sedentarisation and institutionalizing racism, other parts of Europe were undergoing contrasting, anti-discriminatory transformations.

These very different histories, through the past half century and more, have implications for the positionality of Western and Northern European Romany Gypsies and Irish or Scottish Travellers, the majority of whom had, until very recently, survived with their preferred habitation which was rarely housing. By contrast, in former communist Europe, Roma and those who opt for the title Gypsy (pc M. Jakoubek) have adjusted to housing, be it neglected shanty slums or hidden luxurious residences. It follows that any movement by such ethnic minorities to the UK or elsewhere in northern Europe, is as migrants not nomads. Given the discriminatory neglect and impoverishment of huge numbers of Roma or Gypsies throughout parts of newly accessed European countries, it is no surprise that many will seek alternative possibilities, fantasy or reality, in previously inaccessible capitalist Northern Europe.

It was the innovative, good intentions of people such as the President of Finland, in a key EU position, who insisted that countries applying to the EU prove that the conditions of their Roma be substantially improved before accession. There seems little evidence this was complied with. The countries were adept at window dressing.

When delivering a keynote in Berlin in 2004, during a celebratory Roma/Gypsy week, I mentioned, in passing, the plight of Gypsies in Romania. Some were unjustly sent to schools for the mentally disadvantaged. Roma suffered discriminatory segregation in other spheres. As I finished speaking, a government representative from Romania, not waiting for questions from the audience, leapt onto the platform, grabbed the microphone and delivered a monologue. The German interpreter was made to inform us that all Gypsy children were happy, well looked after and in normal schools. Not one was in an inappropriate institution. On and on the Romanian official ranted, staring at me in an accusatory fashion. The German professor and interpreter stood helpless. The time for questions from the floor was conveniently taken up. Thus we moved onto the next item.

It transpired the original representative was to be a Roma. Suddenly he was substituted by this non-Roma, a former pop singer/performer. With long-term experience of public appearances, he was not intimidated. It seemed no coincidence that the original Roma invitee was withheld from the visit to Berlin. Intentionally or not, he might have painted a very different picture of his people. Subsequently, researchers with long-term experience of Roma in Romania, reassured me that the inappropriate schooling for ‘normal’ Roma children was correct. We were then treated to an extensive ‘speech’ rather than informed lecture by the same ageing pop star: all was wonderful for Roma in a Romanian utopia.

This episode gives insights into how the EU could have been misled as to the allegedly egalitarian, enhanced conditions for Roma before accession. Subsequent researchers, years later, have proved otherwise. The occasional media venture has displayed Roma abject poverty. Rather than this being used against the Romanian government’s previous pre accession assurances, it has now been used against migration in a UK media panic before January 2014. In-depth media curiosity, if pursued a decade earlier, could have brought political pressure on the nations seeking EU inclusion.

Mislabelling and Re-labelling

The general ethnographic ignorance in key EU institutions might also explain the bizarre decision by the EU to ban the uttering of the very word ‘Gypsy’ in the public domain. This is what I was indeed instructed to respect in Berlin by my hostess, the anthropology professor, before the 2004 keynote. I was on no account to use the word ‘Gypsy’. I remonstrated this was the name used and still used by the people I lived with and studied for years in England: Adams et al. (1975), Okely (1983) and many subsequent articles all highlighted this self-ascribed label (see Figure 6). Other texts like Kenrick and Puxon (1972), Acton (1974) and Rehfisch’s edited Gypsies, Tinkers and other Travellers (1975), one of the pioneer anthropologists to have lived with Scottish Travellers (1958), did not consider the label racist, but celebratory.

Granted, the label is stigmatized by some in post-communist Europe, but the injustice is for this ban to be extended, contrary to their preference, to those who embrace ‘Gypsy’. A comparison can be made with the Impressionist painters who eventually embraced that description as proud title when originally it had been thrown at them by art critics as a term of abuse. ‘Egyptian’ may have been an outsider label but it has been proudly embraced, through history by many. My Masters student, Illiana, a Bulgarian Roma, whose dissertation I supervised at Oxford, (see Okely, 2011: 25, figure 4) recounted how she had met a Pentecostalist preacher in Sussex. Without explaining the sub text, she excitedly repeated how he had said: ‘We Gypsies’. Finally, she was happy that my use of the label for English Gypsies was accurate because self ascribed.

Ironically, when moving to Edinburgh University in 1990, I was invited to join the Scottish Travellers’ Gypsy organization. They had recently inserted ‘Gypsy’ because the label ‘Travellers’ had become conflated with ‘New Age Travellers’. The latter had no ties with such ethnic groups. They had been demonized for rave parties and subject to mass evictions, indeed extreme violence, by the authorities. Supervising an undergraduate dissertation on this group frequenting South West England, I learned that many were art school graduates. Some naively sold their property and lived off the interest of the invested money. They were not even drop-outs from the lumpen-proletariat, as had been presumed.

Horses tolerated over some Humans

Again there are changes in nomads through time. I supervised a Masters dissertation at Bristol University by a now settled New Traveller who studied yet another emergent group- ‘The Horse-Drawns’ (Howarth, 2012). They chose to live in so-called Gypsy wagons they decorated with extra-terrestial or stellar images, inspired by pagan events at Stonehenge. In contrast to the media demonization of Gypsies, the Horse-Drawns were the source of approving fascination by passing motorists who bought their hand carved ornaments. Whereas my former student argued that the passers-by were entranced mainly by the decorated wagons, I suggested that the English house dwellers were even more fascinated and thus tolerant of these ‘nomads’ huge horses. The latter were often of a vanishing breed, known as carthorses.

As the recent horsemeat scandal confirms, it is generally considered taboo in the dominant hegemony to eat horses, just as it has been among Gypsies (Okely, 1983: ch. 6). Thus nomads with horses will continue to inspire tolerance and compassion among English gorgios, even though some still insist that Gypsies steal children. The horse is also at the heart of upper class British culture. Royalty, especially, celebrate horse racing and show jumping. Both the Queen’s daughter and her grand-daughter, have performed as show jumpers, to Olympic standards. Admittedly, Princess Anne has admitted to eating horsemeat (Daily Mail, 2014: 5). Thus the ‘Horse-Drawns’ are fully sensitized to the sentiments of the British ruling ideology. But, unlike the opening shots of ‘Big Fat Gypsy Wedding’ with the Gypsy wagon as celebratory of the Gypsies’ own traditions, the ‘Horse-Drawns’ are not branded as primitives.

Self-Ascriptions and Political Representation

Inevitably labels change through time, especially after stigmatization. Martin Luther King used the now tabooed word ‘Negro’ in his famous ‘I have a Dream’ speech, half a century ago. This was to be replaced by ‘Black’, then ‘African American’. Granted, the linguistic equivalent of ‘Gypsy’ may have been seen as representing the outsider racist term of abuse by some groups in post-communist Europe. But surely the EU, embracing many nations with different histories and sub-groups should have done its homework. The remarkable Gypsy Council, established in England in the mid 1960s, with representatives of Gypsy descent remains. Should the Council also be outlawed by the EU?

Again this reflects the differing histories within Europe. Kaminski elaborated in his monograph (1980) and our frequent exchanges through the 1970s (Okely, 2012), how communist states appointed representatives for different national or ethnic groups. They were given public recognition and substantial salaries. However, Kaminski argued that these unelected, highly skilled state employees were avoided by Polish Gypsies at grass root level. Such ‘leaders’ were even regarded as ritually polluted. This strategy resonated with the British colonial tradition of inventing and rewarding indigenous ‘leaders’. This indirect rule ensured top down stability throughout the Empire, just as in communist Europe.

In contrast to this hierarchical polity, English Gypsies, and often Irish and Scottish Travellers, as nomads have survived with decentralized strategies (Okely, 1983: Ch 10). One Gypsy male friend, a skilled boxer, declared: “Anyone who says he’s ‘King of the Gypsies’ or our ‘leader’ will have to take on every man in a line at Stowe Fair. He’d have to beat each one in a hand-to-hand fight. He should start with me”. Thus the EU had been less likely to consider the long term and cross-cultural contrasts where there is not an established state tradition of formal, let alone salaried, English Gypsy representatives.

The self-ascribed label Gypsy for the English continues proudly today. As recently as 2012, when I convened a panel at the conference ‘Anthropology in the World’ at the British Museum organised by the Royal Anthropological Institute, two participants happily declared their identity as members of ‘The Gypsy People’. Thus it is extraordinary that, way back in 2003/4, the relevant EU decision-makers could not even consult the literature and political practices from across the Channel. The celebration of ‘Gypsy’ is again confirmed by Smith and Greenfields in: Gypsies and Travellers in housing (2013). David Smith the co-author, and senior lecturer at Greenwich University, is proud to identify his Gypsy heritage. I rest my case against the EU dictat.3

Nomadism Celebrated or Destroyed

In contrast to post-communist states, the English Gypsies still celebrate their long history of nomadism. The tragedy is that they have more recently been forcibly settled. In their case, there continues to be a preference for living in caravan trailers or chalets on kin-based sites. Instead, as Smith and Greenfields reveal (2013), Gypsies and Travellers are now living, against their will, in randomly scattered housing. There is depression, thanks to social isolation and lack of employment once based on multi-occupations and mobility. Gypsy housedwellers on ‘sink estates’ fearing bullying and racism, even have to conceal their ethnicity from neighbour residents.

Ironically, while Gypsies are demonized for allegedly being benefit scroungers, their dependence on and cost to the state would be greatly reduced if, as previously, they were permitted land with planning permission for sites. This could either be on land they purchase or that organized by local councils. Here they would provide their own accommodation, freeing up social or privately rented housing for others for whom there is an ever-growing shortage. A kin-based community, with traditions of shared social care and work partnerships would reinvigorate Gypsy/Traveller possibilities for self-employment. Mental wellbeing would be revived, eliminating the current short termism of prescriptions for anti-depressants and other medication for problems which are side effects of an avoidable politically constructed problem (ibid, 2013).

The background to the multi-million destruction of Dale Farm in Essex is outlined elsewhere (Okely, 2011). In contrast to regular small-scale evictions, this gained near global media publicity. The land had been purchased by Irish Travellers hoping to gain retrospective planning permission, as had worked elsewhere. Meanwhile, the news media remained oblivious to the historical context or deliberately judgmental towards the residents facing eviction. Additionally, celebrity supporters of these demonized Travellers, were mocked as ‘Travellers’ toffs’ (Brennan, 2011).

Such was the media hysteria, I was telephoned by several radio stations. But, as already suggested, any politico-cultural explanation proved too complex (Okely, 1983: Ch. 11). These ‘journalists’ only wanted simple sound bites and rang off. A woman from Radio Five Live asked merely why there were no men, just women and children available to be filmed. They said they would be in touch. No one in the populist media wanted to learn about the context, e.g. the 1994 legislation which abolished the decades long duty to provide sites for Gypsies. Colin Clark and I, along with hundreds, had lobbied outside the House of Commons warning of the consequences. No matter that Gypsies were advised by the legislators to buy their own land.

By 2011, the newly elected Coalition Conservative minister for Communities, Eric Pickles, was determined to set an early example. This was illegal residence on Green Belt he argued. In fact, it was the site of a former council scrap metal yard. The subsequent bulldozing of the chalets and concrete driveways has released multiple toxic chemicals into the atmosphere.

Not long after the dramatically televised eviction, the Coalition government began to relax planning restrictions on building houses on green belt land. The Conservative party had indeed received funding from national building companies, now effective lobbyists. The Daily Telegraph headlined:

‘The ‘huge’ lobbying war chest behind the builders’

Property developers, exposed by the National Trust, ‘will give developers carte blanche to build on large parts of rural England’ (18 October 2011).

More recently Dominic Lawson (2014) has proclaimed:

‘Unbuckle the sacred green belt and the housing crisis is solved’

Thus the Eric Pickles ‘Green Belt’ defence of the destruction of Dale Farm is challenged only when housedwellers and builders’ interests predominate.

Meanwhile the general media ignorance about Dale Farm extended even to the BBC Radio 4’s early morning ‘Today’ programme. I was telephoned and informed that a car would collect me for interview in the Oxford BBC studio the following morning. I asked the names of the presenters that day. When told one would be Evan Davis, I stupidly commented that he knew nothing about Gypsy economic history. His 2010 BBC TV programme about seasonal agricultural workers in Wisbech had analysed the need for foreign migrants in psychological terms, namely the laziness of local housedwellers (‘The day the Immigrants left’, BBC One, 9pm. February 24th 2010). In fact, all that work, for decades, was done by English Gypsies until greater restrictions on their movement. Hitherto, Gypsies provided their own mobile accommodation, not plastic sheeting as shelter for the mainly single and youthful migrants. Farmers welcomed the Gypsies. The law recognized their essential contribution by excusing Gypsies from prosecution for their children’s absence from school during those key months.

Five minutes after my brief, naïve response, the BBC called back. My interview was cancelled. Presumably, it was insupportable to have a woman Professor challenging the expertise of a presenter in a programme, which one BBC producer had justified for excluding female presenters because it was “high testosterone”. Like Davis, I had studied Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Oxford, but would never have explained economic engagement in terms of psychology.

Online, a photograph depicts Davis in front of the Wisbech ‘Historic Fenland Town’ sign. This town was a major landmark for my Gypsy companions and near neighbours. The vast majority travelled there for seasonal fruit and vegetable picking, just as the Scottish Travellers were responsible for the raspberry harvest in North Eastern Scotland. The very place, Wisbech, is highlighted in my monograph (Okely, 1983: 127 and 139).

Primitivism

These examples of movement have been integral to a nomadic history and its cultural celebration. This contrasts with the differing history of Roma from post-communist states such as Romania, Poland, former Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria.

Regrettably, nomadism is demonized by sedentary states, although Gypsies are acceptable as exoticised, distant ‘other’ if elsewhere in time and space. The populist visual media as in ‘Big Fat Gypsy Wedding’ (2011) delighted in another caricature of nomads. Every opening shot of the series began with a horse drawn Gypsy caravan with the gravitas voice-over of Barbara Flynn declaring that ‘the Gypsies had to be dragged into the 21st century’. It was a deliberate fakery using footage of Gypsies on what some Gypsies identify as an annual pilgrimage to fairs, such as Appleby. This is a special occasion to parade the traditional horse drawn wagon. For the rest of the year, or simultaneously Gypsies drive their motorized vehicles with entirely modernized lifestyles.

Back in the 1970s, a market research employee, examining data from a policy project (Adams, Okely et al 1975) noted excitedly the huge, majority percentage of Gypsy families owning motor vehicles. This contrasted dramatically with the dominant housed population where the car ownership percentage was much lower. By definition, this would be the case with a mobile group dependent on towing homes and needing individual transport for work. Nevertheless, what was recorded as normal and widespread by the mid 1970s, was deliberately misrepresented decades later. No one would have declared that the majority non-Gypsy housed working class, without car ownership in the 1970s, were ‘finally dragged’ into the 21st century. The soon-to-be millionaire producers of the Big Fat Gypsy series thrived on racist primitivism, such is the deeply ingrained mythical history of Europe’s fear of the nomad outsider – elusive and uncontrollable. Simultaneously, these nomads have for centuries been economically interconnected with the dominant sedentary society and economy.

To Conclude

Through the centuries, Gypsies have been demonized long after it was a capital offence to be a Gypsy at the end of the 18th century in England (Okely, 1983: 4). While other minorities may have gained greater acceptance, the Gypsies have continued to be an easily imagined and racist scapegoat. Ancient myths and populist stereotypes are given new life by a ruthless, circulation-driven modern media. Traditional, in-depth journalism is overtaken by the bullet point and any arresting image.

1 Since these articles were published, younger researchers, obsessed with ‘new’ theories, have mistakenly claimed that Okely argued that Gypsy identity is merely ‘performance’, thus ignoring key discussions of the principle of descent (Okely, 1983: ch 5).

2 Contrary to a linguist’s claims that ‘Okely has coined the term(s) Gypsiologist’ (Matras 2004 p.75) as ‘an abstract adversary’ (ibid, 65), Liverpool University Press online reveals it’s much earlier use.

3 Perhaps this anthropologist should be more sympathetic towards the EU as octopus-like organization, when even a UK based professor on an EU funded Romani network, attacks a ‘fellow’ academic for allegedly if not deliberately risking ‘confusion among policy makers’:

‘I strongly agree with Judith Okely that the self ascription of groups must be respected….This point serves to illustrate how important it is for academic researchers to get their own terminology right, to avoid further confusion. …in Britain an academic book appeared some years ago that carried the title ‘The Traveller Gypsies’. I’m not familiar with any group in Britain that uses this label as a self-ascription. There are usually either ‘Travellers’ or ‘Gypsies’. The use of the undifferentiated outsider label ….risks stimulating confusion among policy makers and the general public.’

Professor Yaron Matras

(Sent January 31, 2013) romani_studies_network@yahoogroups.com

This was my reply on the network:

‘Contrary to one linguist’s pronouncement, Okely indeed deferred to self-ascription in The Traveller-Gypsies. In the 1970s, the people with whom I lived on English camps, (as participant-observer not one-off interrogator), preferred the self-identifying ‘Traveller’ when interacting with officials, housedwellers and gorgios with questionnaires. These Gypsies then believed ‘Traveller’ to be suitably neutral without stigma. Given compulsory official site provision, the increasingly negative label ‘Gypsy’ dominated public discourse. Officials visiting a newly opened ‘Gypsy’ site, questioned the residents who politely identified themselves as Travellers, causing confusion. My sensitized companions concealed their Gypsy title. But among themselves, in trusting contexts, they used ‘Gypsy’ with pride.

Acton (1974) and Raywid (pc. 2013) confirm the all-embracing, less stigmatized ‘Traveller’ was acceptable in the 1970s to every UK group. Since my 1983 publication, ‘Traveller’ has again changed in public meanings. In contrast to the English Gypsies, it is now linked more specifically with Irish and Scottish Travellers, especially after ‘Tinker’ became negative in gorgio discourse.

However, by the late 1980s, ‘Traveller’ was increasingly demonized with the emergence of ‘New Age’ Travellers, then triggering the 1994 Act, abolishing site provision. Politicians, such as Jack Straw (Labour) and Michael Howard (Conservative), publicly criminalised Travellers of Gypsy heritage. The Gypsy Council’s attempts to prosecute for racial discrimination failed because ‘Gypsies’ were not labelled. Thus any self-ascribed ethnic identity for ‘Traveller’ was laundered and lost to history.

In my text, having noted the self-selected contextual interchangeability, I alternated ‘Gypsy’ and ‘Traveller’ to challenge any reader’s stereotypes. Unfortunately, decades later, the authenticity of my fieldwork among Gypsies is deemed questionable because ‘among an unspecified community of “Travellers” ’ (Matras 2010: 131). Ethnic denial is reproduced.

As for my title choice, I wanted to emphasise the people’s own public preference for Traveller, in contrast to the then more often privately selected Gypsy. A title such as ‘The Gypsy-Travellers’ would have reinforced the populist privileging of ‘real’ Gypsies in contrast to implicitly downgraded ‘other Travellers’.

Finally, I was inspired by Andrew McCormick’s 1907 classic The Tinkler-Gypsies, a scholarly and first hand overview of tent dwelling nomads, mainly in Scotland. McCormick’s prioritizing of the then positive ‘Tinkler’ emphasized the self-selected external label for groups, often submerged with then over generalized Gypsies. The Traveller-Gypsies deliberately confronted received stereotypes, challenging readers to think through a puzzle.….

Thanks for the network’s informative, creative exchange where a united front against racism is surely the priority, not petty imagined rivalry.’

Professor Judith Okely

(Sent February 05, 2013)

Judith Okely, j.m.okely@hull.ac.uk

Acton, T. (1974) Gypsy politics and social change. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Adams, B. and Okely, J., et al (1975) Gypsies and Government Policy in England. Heinemann Educational Books.

Brennan, Z. (2011) ‘Travellers’ toffs’, Daily Mail, 1 October.

Burrell, I. (2014) ‘Shock and Four’. Profile: Jay Hunt, The Independent, 11 January.

Clifford, J. and Marcus, G. (1986) (eds) Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California press.

Cotten, R.M. (1954) An Anthropologist looks at Gypsiology. J.G.L.S. third series, vol. XXXIII, 3-4, 107-20.

Cotton, R.M. (1955) An Anthropologist looks at Gypsiology. J.G.L.S. third series, vol. XXXIV, 1-2, 20-37.

Crawford, P. and Turton, D. (eds) (1992) Film as Ethnography. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Fabian J. and Ries, J. (eds) (2008) Romani/Gypsy cultures in new perspectives. Leipzig: Leipzig University.

Doughty, L. (2013) ‘Roma myths revisited’, The Guardian, 23 October.

Guy, W. (1975) ‘The Attempt of Socialist Czechoslovakia to Assimilate its Gypsy Population’, Phd. thesis. Bristol: University of Bristol.

Howarth, A. (2012) ‘Horsedrawns’, MA dissertation. Bristol: Bristol University.

Humphreys, M. (1996) Empty Cradles. London: Random House.

Jakoubek M. and Budilova, L. ‘Interview’ Acta 1/11 University of Pilsen.

Jenkins, S. (2014) ‘We are all living on Benefits’, The Guardian, 22 January.

Kaminski, I.M. (1980) The State of ambiguity: studies of Gypsy refugees. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Kenrick, D. and Puxon, G. (1972) The Destiny of Europe’s Gypsies. London: Heinemann.

Lawson, D. (2014) ‘Unbuckle the sacred green belt and the housing crisis is solved’, The Sunday Times, 13 April.

Leach, E. (1967) An Anthropologist’s reflections on a Social survey, In: D. Jongmans and P. Gutkind (eds) Anthropologists in the Field. Assen: von Gorcum: 75-88.

Matras, Y. (2004) The Role of Language in Mystifying and De-mystifying Gypsy Identity, In: N. Saul and S. Tebbutt (eds) The Role of the Romany. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. CrossRef link

Matras, Y. (2010) Romani in Britain: The Afterlife of a Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. CrossRef link

McCormick, A. (1907) The Tinkler-Gypsies. Edinburgh, Dumfries.

McLuhan, M. (1964) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: Signet.

Okely, J. (1983) The Traveller-Gypsies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. CrossRef link

Okely, J. (1992) Anthropology and autobiography: participatory experience and embodied knowledge, In: J. Okely and H. Callaway (eds) Anthropology and Autobiography. London: Routledge. CrossRef link

Okely, J. (1994) Thinking through fieldwork, In: A. Bryman and R.G. Burgess, (eds) Analyzing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge.

Okely, J. (1996) ‘Trading Stereotypes’ Ch.3, In: J. Okely Own or Other Culture. London: Routledge.

Okely, J. (1997) Some political consequences of theories of Gypsy ethnicity: the place of the intellectual, In: A. James, J. Hockey and A. Dawson (eds) After Writing Culture. London: Routledge.

Okely, J. (2011) ‘The Dale Farm eviction: interview with Judith Okely, on Gypsies and Travellers’ with G. Houtman. Anthropology Today, 27, 6, 24-27. CrossRef link

Okely, J. (2008) Knowing without Notes, In: N. Halstead, E. Hirsch and J. Okely (eds) Knowing how to Know: Fieldwork and the Ethnographic Present. Oxford: Berghahn, pp. 55-74.

Okely, J. (2012) Anthropological Practice: fieldwork and the ethnographic method. London: Bloomsbury.

Okely, J. and H. Callaway (eds) (1992) Anthropology and Autobiography. London: Routledge. CrossRef link

Ries, J. (2007) Welten Wanderer. Wurzburg: Ergon.

Rehfisch, F. (1958) The Tinkers of Perthshire and Aberdeenshire. Edinburgh: School of Scottish Studies (unpublished).

Rehfisch, F. (1975) (ed) Gypsies, Tinkers and other Travellers. London: Academic.

Sixsmith, M. (2009) Philomena: A Mother, Her Son and a Fifty-year Search. London: Pan books.

Smith, D.M. and Greenfields, M. (2013) Gypsies and Travellers in housing: the decline of nomadism. Bristol: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Sutherland, A. (1975) Gypsies: the Hidden Americans. London: Tavistock.

Thompson, T.W. (1922) The uncleanliness of women among English Gypsies. Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society 3rd series, 2, 3, 113-39.

Yates, S. (2004) Doing Social Science Research. Open University.