Abstract

This paper examines the direction of public policy in the UK towards the voluntary sector since 1997. It does this by asking what lessons the new Labour government of Keir Starmer can learn from the period of New Labour government (1997-2010) and the Conservative Party led majority or coalition governments (2010-2024). We look at each period through four lenses: what was the dominant political rhetoric towards the voluntary sector, what key policies the government enacted, which major government funding decisions impacted on the voluntary sector, and how different governments engaged the sector in periods of crisis (such as the financial crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic). The incoming Labour government of 2024 has been almost silent on how it sees its relationship with the voluntary sector, except for announcements about partnership working and the common refrain of engaging communities. This is in sharp contrast to 1997 and 2010: the incoming parties on both occasions had relatively well-formed programmes for government. In part this may reflect the decline in programmatic government and a period of incredible turbulence in British politics. However, the paper concludes that this is a significant risk. Whilst there are lessons from previous governments, the new Labour government of 2024 faces far greater challenges and risks of multiple crises than its predecessors. Identifying a genuine partnership and vision with the diversity of the voluntary sector is one of many pressing issues it faces.

Introduction

Different political regimes have significantly shaped the diverse policy and practice positions of the voluntary sector (Macmillan, 2020). At the heart of current debate is how the policy agendas of the new Labour government elected on 4 July 2024 may engage and impact upon the voluntary sector. On the one hand, with a large parliamentary majority and after 14 years of Conservative led government (in coalition and with a majority) 2024 may come to be seen as a major political disjuncture and a recasting of the policy landscape; perhaps similar to the 1945, 1979 and 1997 UK General Elections. On the other hand, with a weak economy and even weaker prospects for increasing public expenditure, the Labour government may believe its options are severely constrained.

In opposition, the Labour Party said relatively little about how it sees the role of the voluntary sector. The 2024 Labour Party manifesto only mentions the voluntary sector twice, once in relation to employment support for offenders and once in relation to supporting children out of poverty. Charity is not mentioned once although community (usually as a fuzzy term approximating to a host of things from social groups to places) is used 16 times. Keir Starmer’s January 2024 speech to voluntary sector leaders identified many of the roles that charities and voluntary action play but did not reveal any new policy ideas. Its main call was to voluntary sector leaders to work in partnership with a future Labour government. During the recent Labour Party conference in September 2024 the government announced ‘the Covenant’ as a new agreement to reset and improve the state-sector relationship. However, there is scepticism about whether this new partnership pledge is not just warm words. There seems to be considerable scope for the sector’s role in shaping, implementing or challenging future policy to be defined.

This review paper explores what lessons the new Labour government may draw from 1997 and 2010. It explores four interrelated themes: the rhetoric towards the voluntary sector, public policy commitments, funding commitments, and the response and engagement of the sector in periods of crisis (the 2008 global financial crisis and its recessionary aftermath) and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. The impacts of policy commitments or external shocks (such as crises) are rarely even. This is true for the impact on the voluntary sector, as the sector sought to address manifold challenges and their long-term consequences (Dayson et al., 2021; Rees et al., 2024). The binary state-voluntary sector relationship also needs to be seen as limited: there will always be churn and change in the sector, but different policy agendas may bring winners and losers (Taylor et al., 2016; Rees et al., 2024).

With a careful assessment of policy documents around agendas including the Compact and the Big Society, the paper concludes by exploring what ‘who cares’ for the voluntary sector has meant and what lessons can be drawn for the new government. The concept of care is seen from a critical perspective on the voluntary sector’s resources in terms of income and finances and capacity in terms of volunteers and workforce. However, much more could be said about ‘care.’ This largely reflects a resource-based model – i.e. the more we spend on voluntary sector organisations, the more we care about them. Some might argue that the sector requires other support, provided through infrastructure and other bodies. A right-leaning position might argue that it is not the state’s responsibility to ‘care’ for a sector – that what it should care about is outcomes and not how they are delivered.

This review paper charts the historical dilemmas facing the voluntary sector and how this has led to series of unsettlements and uncertainties. It explores the state-voluntary sector relationships in England from 1997 to date (2024) highlighting the key themes of changes in these relationships. The final part revisits the sector’s current dilemmas and considers what likely trajectories or opportunities might open in the post-election environment.

Methodology and approach

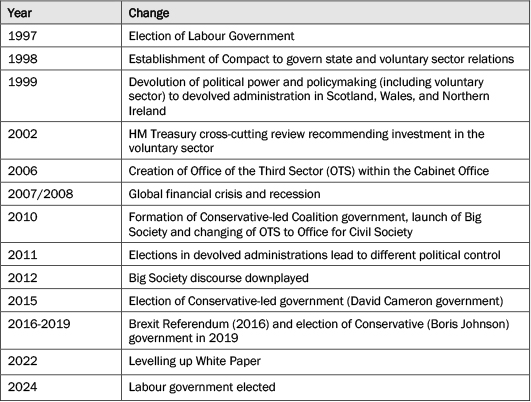

Data for this review paper come primarily from reflections on publicly available policy papers and voluntary sector research reports and studies over the last three decades. Table 1 below shows the broad timeline of relevant political and policy changes since 1997.

The paper explores national and mainstream policies with a bias towards England, which demands a note of caution towards the generalisation of state-voluntary relationships in the devolved nations – Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

Lessons from previous governments

Three key themes emerged from the review of existing evidence about the state-sector relationship. The first was the mainstreaming of the voluntary sector in public service delivery through partnership working. The second was the growing significance placed on ‘value for money’ from 2007, when public sector spending began to overshoot tax receipts. These pressures were amplified by the effects of the global financial crisis and government intervention into financial markets. The third key theme broadly encompassed the era of policy silence on the voluntary sector and the demise of the Big Society agenda from 2013 onwards.

The Partnership Era: late 1990s to 2000s

The dynamics of the relationships between the state and the voluntary sector in the early 1990s are said to be rooted in the idea of partnership working (Powell & Exworthy, 2002). The formalisation of this agenda was heralded by the government’s ‘Third Way’ philosophy, which sought to move beyond simply defined approaches where either the state or the market delivers goods and services to meet social needs (Giddens, 2013). An example of this approach is the ‘continuation’ or ‘extension’ of a quasi-market economy in public services where a mix of providers from the public, private and voluntary sectors are supported and encouraged by the state to provide welfare services to long term unemployed and economically inactive citizens (Alcock & Scott, 2002). The position of the New Labour government was complex: it sought to invest in and build the capacity of the voluntary sector but also to open contracts to competitive tendering instead of grants. To formalise the partnership (non-legal bidding agreement) between the state and the sector, the Compact was introduced in 1998 as a ‘concordat’ to foster practical working relations, collaboration, and cooperation between the two sectors as recommended by the Deakin Commission in 1996 (Deakin Commission, 1996; Davies, 2002).

As a follow up to its manifesto commitments, the Labour government established a ministerial taskforce in Whitehall to coordinate the development of the Compact and modernise the relationship between local government and the voluntary sector. A key mandate of the Compact was to improve relations between the state and the voluntary sector, followed by the development of local Compacts between the sector and local authorities (Craig & Taylor, 2002). The approach hinged on the notion that the voluntary sector is a means to better reach a diversity of people; and from that, that active citizenship supports the delivery of better and more responsible public services. Some researchers have noted that this period witnessed the proliferation of voluntary sector organisations’ involvement in service delivery as seen in the growth in size, scale, and representation of the sector in public service delivery, policy planning and debates (Alcock, 2012b; Damm, 2012; Taylor et al., 2016).

Following a ‘cross-cutting review’ (HM Treasury, 2002), the Labour government rolled out a series of capacity-building and funding projects to support the sector and to create a level playing field in service provision. The first is the Futurebuilders fund over a period of three years (2005-2007), extended from 2008-2010 with an additional £90 million, making a total of £215 million (Wells, 2012). The Communitybuilders fund, worth £70 million, was launched by the Department of Communities and Local Government and the Office of Third Sector in 2008 to support small local and community-based organisations. Meanwhile, the £150 million ChangeUp programme was introduced in 2004 to boost the capacity of infrastructure bodies (such as local Councils for Voluntary Service) to support voluntary organisations. Other contemporary initiatives included the Adventure Capital Fund and the health-focused Social Enterprise Investment Fund (Alcock, 2012a; Alcock et al., 2012a; Alcock, 2016a). The rationale of New Labour from the cross-cutting review onwards was to increase the sector’s capacity to deliver public services (Macmillan, 2010).

The government also enhanced the sector’s role in promoting citizenship and civic engagement through the creation of the Civil Renewal Unit in the Home Office in England in 2004 (Milbourne, 2009). Other relevant policy initiatives included a Treasury-led Charity Tax Review announced in the 1997 Budget, and the creation of the Active Community Unit (formerly, the Voluntary and Community Unit, and Voluntary Services Unit) at the Home Office (Kendall, 2003).

From around 2010 a more animated debate about the mainstreaming of the voluntary sector began to emerge (Kendall, 2003) with a particular focus on its capacity and independence. The central argument was that involvement in the delivery of public services had increasingly led to a diminishing of the sector’s distinctive voice and position, and that the sector had to some extent been co-opted as part of a shadow state (Milbourne, 2013; Duncan, 2018). While there is an argument about whether ‘mainstreaming’ had gone too far, the reality is that the sector continued to be treated as an addendum (Milbourne, 2013). This is evidenced by the historical trend where the state recognised the sector’s expertise on one hand, but at the same time constrained its independence through the marketisation of welfare, increased regulation and monitoring, and dominant managerial cultures (Milbourne, 2013). Several social policy researchers have critiqued the development of the state-sector relationship for promoting a process of homogenisation among voluntary organisations (Milbourne & Murray, 2014; Milbourne & Cushman, 2015).Others argued that the sector is vulnerable to mission drift (Alcock et al., 2004; Cairns et al., 2006; Rees, 2008). Concerns were expressed over how the competitive contracting landscape affected voluntary organisations’ internal structures and capacity to adapt to changing funding rules and variations in expected outcomes or results (Buckingham, 2012; Harlock, 2014).

In practice, the Labour government’s support, seen through the hyperactive mainstreaming and proliferation of the voluntary sector, may not have entirely stemmed out of interest in promoting the sector’s comparative advantage. Rather, it can be seen as part of a focus on improving outcomes across key areas of public policy, with an expectation that funding followed those providers most able to deliver better outcomes.

Austerity and Big Society (2008/2010-2012)

Public expenditure from 2007 began to rise faster than government receipts from taxation. This gap was amplified by the global financial crisis. The Coalition government formed in 2010 sought to distinguish its approach to the voluntary sector. Alcock suggests that this was done in three ways: 1) the term third sector was replaced by civil society; 2) the harnessing ideas of the ‘third way’ were replaced with the Big Society; and most significantly, 3) the Coalition government embarked on an unprecedented programme of public expenditure cuts (Alcock, 2010; 2012a).

The Conservative Party manifesto of 2010 provided a clear statement of its programme for government. The coalition with the Liberal Democrats changed the substance of the manifesto relatively little. The manifesto’s centrepiece was the rapid imposition of public expenditure cuts. Areas where the voluntary sector may have had a significant role, from youth services to partnerships with government or quangos, rapidly disappeared.

A central change was the largescale reform of welfare policy, and especially work-related benefits. The Department for Work and Pensions moved quickly to cut welfare expenditure and increase conditionality (or sanctions) for those receiving work-related benefits. The introduction of the Work Programme in 2011 included contractual commitments that providers would deliver outcomes in terms of benefit recipients moving into employment (Sanderson et al., 2018). Large, mainly private sector providers were given the flexibility to design and deliver services dependent on sustained outcomes. Subcontracting practices were introduced with the aim of improving services (particularly in terms of value for money) whilst managing the risks posed, especially in payment-by-results systems (Finn, 2011; 2012). The Work Programme replaced the previous fragmented programmes: 19 prime providers were commissioned to deliver services to achieve long-term employment outcomes (Finn, 2011). The rationale for this approach was to incentivise providers to utilise innovative ways to achieve expected results. The key argument was that more integrated services and better results would be achieved by transferring the responsibilities for service delivery and managing complex supply chains to the selected prime providers (Finn, 2011; Rees et al., 2015).

Alongside spending cuts and public service restructuring, David Cameron’s Big Society became the dominant rhetoric: the UK’s broken society would be addressed by expanding government support for the voluntary sector (Evans, 2011). The previous vertical relational support between government and the voluntary sector was replaced by a model of horizontal funding and policymaking (Kendall, 2003; Alcock, 2012a). There was an ideological shift from a broadly social democratic and managerialist approach to public policy under Labour to one informed strongly by libertarian paternalism. This is reflected in agendas from the Localism Act (arguably seeking to give ‘local’ people more say over local policy) through to the launch of Big Society Capital (to support a market for greater social action (Jones at al., 2010; Corbett & Walker, 2013). According to Alcock (2012a), the Big Society was aimed at promoting voluntary action and improving inclusion by returning power from the state to the citizen and putting social change in the hands of local communities. But what was cast aside with this agenda was a commitment to some form of territorial justice and redistribution between localities and regions (Wells, 2011).

However, the Big Society agenda turned out to be less significant than the political rhetoric suggested. What happened was the end of hyperactive mainstreaming and an intense withdrawal of state support, projected through austerity and budget cuts, greater use of contracts for services, and associated punitive regulatory and accountability frameworks (Smerdon, 2009; Alcock, 2012a). One prominent policy and public service delivery shift was the outsourcing of services in a more competitive quasi-market where private, public and voluntary organisations competed for resources to provide services (Taylor et al., 2016).

These policy changes suggest that in the state’s commitment to reforming the delivery of public services, the voluntary sector was not given enough priority (Alcock, 2012a). This claim was supported by developments such as the emergency budget in summer 2010 followed by the autumn 2010 spending review, and the commitment of the government to cut national spending programmes in addition to reductions in local authority budgets. An effect was to lessen the involvement of voluntary organisations in public service provision, leading to a perception that the sector was being squeezed out (Damm, 2012). While there is not much evidence either to support or refute this claim, it is evident that government support for the voluntary sector declined because of spending cuts, and that the environment of public service provision became more competitive than relational.

Policy silence (from 2013)

The Big Society agenda of giving back power to the community was critiqued by many for its lack of powers to support local and small organisations or to raise communities’ capacity to engage in voluntary action (Corbett & Walker, 2013). The Big Society tapped into a public sense of community solidarity and mobilising but failed to address the fundamental differences and power imbalance in the relationship between the state and the voluntary sector. As the Work Programme example highlights, national and local government funders increasingly expected more from their funding in terms of measurement and demonstration of outcomes, moving from grants to contractual relationships.

In addition, the landscape of public service provision has become fragmented, which some analysts suggest has led to a decline in the health and sustainability of voluntary organisations, especially small and medium-sized ones (Damm, 2012). While the contracting out of public services is not new (the process was introduced with the Manpower Service Commission in the 1980s), the emphasis on outcome-based payment for performance in terms of job starts and retention increased, making the process more stringent for many voluntary organisations.

The argument behind the novel payment-for-result approach (DWP, 2012) hinged on the promotion of a flexible and effective public service structure based on the condition of meeting certain minimum service standards, from bidding to the implementation and evaluation phases (Foster et al., 2014). A key innovation was the development of the prime-model intelligent commissioning and funding principles, based on quality provision and cost containment (value for money). The prime model provides a system where public service contracts are awarded to large organisations which sub-contract to smaller and local service providers or a supply chain of specialist and frontline service providers (Rees et al., 2022). As argued by Finn (2011), the awarding of large contracts to a few large organisations allows for a long-term funding approach and for the state to reap economies of scale through trade-offs between cost and quality of services and outcomes.

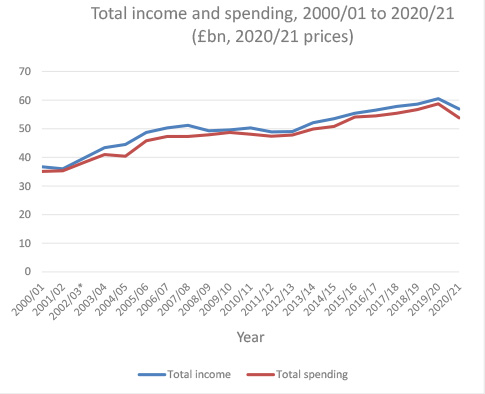

Several authors have identified how voluntary sector organisations are struggling with the turbulent and changing policy and funding landscape (Rees et al., 2022). The NCVO’s annual UK Civil Society Almanac reveals that the sector’s total income in 2020/21 was £56.9bn, compared to £53.8bn in spending (NCVO, 2023). The Almanac shows that whilst the initial programme of austerity led to a plateauing of income, it did not necessarily lead to an overall fall in income across the sector (See NCVO, 2023, Figure 1 below). In fact, the only decline in income came towards the end of the 2010s.

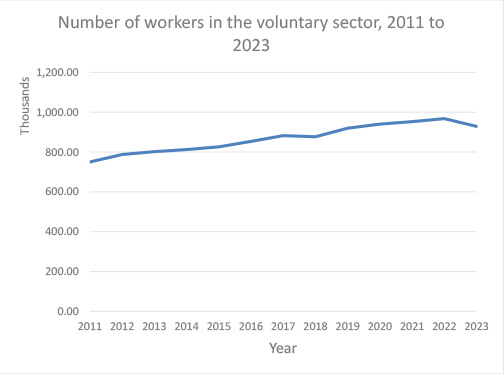

Furthermore, since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the first quarter of 2020, the voluntary sector workforce increased by about 12,000 or four per cent until 2022. However, it then decreased by four per cent from 2022 to 2023, back to 2019 levels of employment. In contrast, the public sector workforce has grown each year, with a two per cent increase from 2022. The private sector (which employs 73 per cent of the total workforce) has remained largely the same size.

The picture is far worse for smaller voluntary organisations who continue to bear the post-COVID-19 economic brunt. Over the longer term, larger organisations have received an increasing amount and share of the sector’s total income, while the income of smaller organisations has shrunk at a much faster rate. The outlook at the local level is more critical as local authority funding fell by 23 per cent (more than £13bn) between 2009/10 and 2020/21 (Pro Bono Economics, 2024). In December 2022 most voluntary sector workers (56 per cent) were employed by organisations with between one to 49 workers with one quarter (25 per cent) working for organisations with one to ten employees. Almost a third (31 per cent) worked for organisations with between 50 and 499 employees and eight per cent worked for organisations with over 500 staff (NCVO, 2023).

What sectoral income levels do not reveal adequately are the increasing burdens caused by rising demand for services. A key cause has been the prolonged period of austerity, increasing levels of poverty and rapidly growing challenges across a range of service areas (from homelessness, to support for young people and mental health, to demands on social care). The income and expenditure picture painted by the Almanacs masks rapidly growing pressures on voluntary organisations.

Discussion and conclusion

The Voluntary Sector amidst its series of unsettlements and uncertainties and navigating the road ahead

In this review paper, we have explored three decades of the state’s approach to the voluntary sector and evidenced a direction of travel in which the landscape of voluntary action has remained unresolved. There are three main themes to this. The first concerns episodes of crises such as the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic that saw public policies and state support geared towards mobilising devolved voluntary action involving collaboration and partnership working with local and community-based voluntary organisations. The second highlights how the growth in spending on public services came to a grinding halt, leading to a shift in focus from building capacity to securing outcomes for the exchequer. The third theme highlights a period where the government began to mainstream policy and funding agendas around contracting, particularly through the payment by results approach that saw many small and medium-sized voluntary sector organisations grappling for financial stability amidst increasing demand for services.

Acknowledging the relatively long years of silence on relationships between the state and the sector, during the election campaign in 2024 Labour leader Kier Starmer pledged to ‘renew’ the relationship between government and voluntary sector (including charities) in his vision for a ‘society of service.’ This would involve an action plan to harness civil society by working in partnership to achieve the Labour Party’s five missions of housebuilding, energy, the NHS, policing and increasing opportunities for all. According to Starmer, the government’s focus is to build a mission-led government which sees civil society as one of the three key engines for renewal, working alongside the public and private sectors (Civil Society, 2024). This position was elaborated by the former Shadow Civil Society Minister, Lilian Greenwood, who highlighted her plans to develop a new strategy (a Covenant), and for civil society to be involved in developing this partnership (Civil Society, 2024).

Rhetoric

The incoming Labour government has said very little about its relationship with the voluntary sector. This is in marked contrast to the New Labour government in 1997 and the Conservative led coalition with the Liberal Democrats in 2010. In 1997, the voluntary sector, rebranded as the Third Sector, was closely aligned to the new politics and policy of the third way. Relationships with the voluntary sector represented a new way of doing government, or rather a model of governance in which partnership with the private sector and the third sector was key.

David Cameron in 2009 announced the Big Society and seized upon the opportunity presented by partnership with the voluntary sector to detoxify the Conservative Party and to develop an alternative approach to welfare policy (both to New Labour and Thatcherism) (Wells, 2011). In spending terms, the Big Society was not much more than a slogan, but it carefully signalled an ideological shift both towards libertarianism but also (in contrast with Thatcherism) towards some concern with society.

The Labour Party in 2024 has not yet signalled any such agenda. Its manifesto was relatively silent on the voluntary sector, although compared with the 1997 and 2010 election manifestos of both major parties it is silent on most things. The era of manifestos as setting out a programme for government may be over.

Key policies

Both New Labour and the Conservative led coalition launched many policies which impacted on the voluntary sector. New Labour had prepared an extensive agenda in opposition which, whilst it was not fully formed, nonetheless presented some clear programmes of work. Central amongst these was the focus on combatting social exclusion, especially at a neighbourhood scale. The approach New Labour took, notably in the National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal and its flagship New Deal for Communities programme, whilst not making the voluntary sector centre stage, saw the importance of partnership working with community organisations at a local level. New Labour’s second term and its focus on ‘delivery’, especially in relation to public services, brought a clear focus for expanding the voluntary sector’s role in service delivery, driven especially by a Treasury’s cross-cutting review.

The Conservative led coalition also had clear programmes to implement. Whilst much work had already been done to establish Big Society Capital, the government quickly moved to shift the focus of the Big Lottery (towards community level social action and away from anything close to public services). The political benefits of the Big Society brand were lost by 2012 as the government focused increasingly on delivering its programme of austerity and welfare reform. An alternative reading, however, is that the Big Society fully achieved its purpose, which was primarily to for the state to have a less interventionist role in the voluntary sector. This is called into question by the passing of the 2014 Transparency of Lobbying, Non-Party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act (also known as the Lobbying Act). It was a direct attempt to limit the scope of charities’ campaigning, especially around election periods. It suggests that the rhetoric of libertarianism was acceptable for the Conservative government only as long as independent organisations did not seek to challenge and criticise government policies.

At the time of writing the new Labour government has not signalled any new policies towards the sector. It thus appears that existing (primarily Conservative) policies will be maintained in the short term. Any change, including charity legislation, is likely to be technocratic rather than informed by a wider government narrative.

Funding

The New Labour government of 1997 inherited relatively benign economic conditions. Through targeted tax rises and growing Treasury receipts from economic growth, funding was found to support major government spending commitments, especially to keynote policies including the New Deal for Communities, Sure Start and the employment New Deals alongside increased investment in schools and incentives for employment (such as tax credits). From 2001 the voluntary sector benefited considerably from a rising tide of public expenditure. Whilst this began to be squeezed by the late 2000s, it was generally a period of growth.

The 2010 election brought this buoyant period to a standstill. In the short term, cuts led to the withdrawal of services and to a greater search for alternative revenue streams. Adept voluntary organisations entered increasingly competitive markets to deliver services under contract. The full impact of the cuts began to be fully apparent by the end of the 2010s. The voluntary sector was squeezed by a smaller revenue base coupled with a growing demand for services.

The incoming Labour government is unlikely to announce major new social programmes that may benefit the sector. Some attempts to address the funding crisis in local government may have medium term impacts. For midsized charities delivering public services the prospects for new support appear limited.

Responding to crises

The 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic were both (largely) unexpected shocks. The global financial crisis was essentially an economic shock; it presaged financial pressures from austerity and for large charities with endowments wiped out asset value gains of the 2000s. But it was time limited, or at least the measures taken to stabilise national and global economies brought medium term sustainability. The COVID-19 pandemic was a crisis of a different order which contained a major economic shock but also wide-ranging health and social crises which are unlikely to be short lived.

Arguably the Labour government of 2024 comes to power in a period of polycrisis in the form of international conflict, the climate emergency, weak economic prospects and growing social pressures. In many ways this exposes the breadth of the voluntary sector and whilst at its core is underpinned by voluntarism, charity and civic action, in its organisational form it is more diverse at any point in its history. Voluntary action is directed to the multitude of crises but very few organisations span these crises.

This presents challenges and opportunities for the sector and for government. Whilst Keir Starmer’s speech in January 2024 talked of partnership between state and sector, the crises facing societies suggest that this relationship needs to urgently go beyond funding and policy debates and towards finding a larger and more purposeful common vision. Arguably, more action is needed to ensure the state’s commitment to the sector is operationalised. This presents a huge opportunity for the voluntary sector to take a fresh approach to deepen its value and to thrive, particularly the small and local organisations that are struggling to keep community public services alive. There is also an urgent need to find a sustainable funding arrangement that would ease the local streams of funding, particularly between local councils who are supporting the local and small voluntary sector organisations that advocate for marginalised people but are themselves being marginalised in the landscape of public and welfare service provision.

Oluwaferanmi Adeyemo, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research (CRESR), Sheffield Hallam University. Email: O.adeyemo@shu.ac.uk

Alcock, P. (2010). A strategic unity: defining the third sector in the UK. Voluntary Sector Review, 1(1), 5-24. CrossRef link

Alcock, P. (2012a). The Big Society: a new policy environment for the third sector? Working Paper. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

Alcock, P. (2012b). New Policy Spaces: The Impact of Devolution on Third Sector Policy in the UK. Social Policy & Administration, 46, 219-238. CrossRef link

Alcock, P. (2016a). Two: The history of third sector service delivery in the UK. In J. Rees & D. Mullins (eds), The Third Sector Delivering Public Services. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Alcock, P. (2016b). From Partnership to the Big Society: The Third Sector Policy Regime in the UK. Nonprofit Policy Forum, 7(2), 95-116. CrossRef link

Alcock, P., Brannelly, T. & Ross, L. (2004). Formality or Flexibility? Voluntary Sector Contracting in Social Care and Health. Birmingham, University of Birmingham.

Alcock, P., Kendall, J., & Parry, J. (2012a). From the third sector to the Big Society: consensus or contention in the 2010 UK General Election? Voluntary Sector Review, 3(3), 347-363. CrossRef link

Alcock, P., & Scott, D. (2002). Eight: Partnerships with the voluntary sector: can Compacts work? In C. Glendinning, M. Powell & K. Rummery (eds), Partnerships, New Labour, and the governance of welfare. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Buckingham, H. (2012). Capturing diversity: a typology of third sector organisations’ responses to contracting based on empirical evidence from homelessness services. Journal of Social Policy, 41(3), 569-589. CrossRef link

Cairns, B., Harris, M., & Hutchison, R. (2006). Servants of the Community or Agents of Government? The role of community-based organisations and their contribution to public services delivery and civil renewal. London: IVAR.

Civil Society. (2024). Charities welcome Starmer plans for sector partnership and ‘society of service’. Civil Society News, January, 2024. https://www.civilsociety.co.uk/news/starmer-pledges-to-form-partnership-with-charities-and-plans-society-of-service.html

Corbett, S., & Walker, A. (2013). The big society: Rediscovery of ‘the social’ or rhetorical fig-leaf for neo-liberalism? Critical Social Policy, 33(3), 451-472. CrossRef link

Craig, G., & Taylor, M. (2002). Nine: Dangerous liaisons: local government and the voluntary and community sectors. In C. Glendinning, M. Powell & K. Rummery (eds), Partnerships, New Labour and the governance of welfare. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Damm, C. (2012). The third sector delivering employment services: an evidence review. http://tsrc.ac.uk/Research/ServiceDeliverySD/Thethirdsectordeliveringemploymentservices/tabid/873/Default.aspx

Davies, J. S. (2002). Eleven: Regeneration partnerships under New Labour: a case of creeping centralisation. In C. Glendinning, M. Powell & K. Rummery (eds), Partnerships, New Labour, and the governance of welfare. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Dayson, C., Baker, L., Rees, J., Bennett, E., Patmore, B., Turner, K., Jacklin-Jarvis, C., & Terry, V. (2021). The ‘value of small’ in a big crisis: The distinctive contribution, value, and experiences of smaller charities in England and Wales during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sheffield Hallam University.

Deakin Commission (1996). Meeting the Challenge of Change: Voluntary Action into the 21st Century, Report of the Commission on the Future of the Voluntary Sector in England. London: NCVO.

Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) (2012). The Work Programme. http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/the-work-programme.pdf

Duncan, S. (2018). Linda Milbourne and Ursula Murray (eds) (2017) Civil society organizations in turbulent times: A gilded web? Voluntary Sector Review, 9(1), 115. CrossRef link

Evans, K. (2011). ‘Big Society’ in the UK: A policy review. Children & Society, 25(2), 164-171. CrossRef link

Finn, D. (2011). The design of the Work Programme in international context. National Audit Office.

Finn, D. (2012). Subcontracting in public employment services: the design and delivery of ‘outcome based’ and ‘black box’ contracts: analytical paper. The European Commission.

Giddens, A. (2013). The third way and its critics. John Wiley & Sons.

Foster, S., Metcalf, H., Purvis, A., Lanceley, L., Foster, R., Lane, P., Tufekci, L., Rolfe, H., Newton, B., Bertram, C., & Garlick, M. (2014). Work Programme evaluation: operation of the commissioning model, finance and programme delivery. London: Department for Work and Pensions. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a804c9440f0b62302692ae6/rr893-summary.pdf

Harlock, J. (2014). Diversity and ambiguity in the English third sector: Responding to contracts and competition in public service delivery. In T. Brandsen, W. Trommel & B Verschuere (eds), Manufacturing civil society: Principles, practices and effects (pp. 34-53). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. CrossRef link

HM Treasury (2002). The role of the voluntary and community sector in service delivery: A cross-cutting review. London: HM Treasury.

Jones, R., Pykett, J., & Whitehead, M. (2010). Big society’s little nudges: The changing politics of health care in an age of austerity. Political Insight, 1(3), 85-87. CrossRef link

Kendall, J. (2003). The Voluntary Sector: Comparative Perspectives in the UK (1st ed.). Routledge. CrossRef link

Macmillan, R. (2010). The third sector delivering public services: an evidence review.

Macmillan, R. (2020). Somewhere over the rainbow – third sector research in and beyond coronavirus. Voluntary Sector Review, 11(2), 129-36. CrossRef link

Milbourne, L. (2009). Remodelling the Third Sector: Advancing Collaboration or Competition in Community-Based Initiatives. Journal of Social Policy, 38(2), 277-97. CrossRef link

Milbourne, L. (2013). Values and visions for a future voluntary sector? In L. Milbourne (ed), Voluntary Sector in Transition (pp. 203-232). Policy Press. CrossRef link

Milbourne, L., & Murray, U. (2014). Governmental organisations: does size matter? Policy and politics, 16, 17 September, Bristol.

Milbourne, L., & Cushman, M. (2015). Complying, transforming or resisting in the new austerity? Realigning social welfare and independent action among English voluntary organisations. Journal of Social Policy, 44(3), 463-485. CrossRef link

NCVO (2023, October 12). Workforce: UK Civil Society Almanac 2023. National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO). https://www.ncvo.org.uk/news-and-insights/news-index/uk-civil-society-almanac-2023/workforce/

Powell, M., & Exworthy, M. (2002). Two: Partnerships, quasi-networks and social policy. In C. Glendinning, M. Powell & K. Rummery (eds), Partnerships, New Labour, and the governance of welfare. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Pro Bono Economics (2024, February 29). Turmoil in local government threatens charity services. Pro Bono Economics. https://www.probonoeconomics.com/news/turmoil-in-local-government-threatens-charity-services

Rees, J. (2008). Who Delivers Services? A Study of Involvement in and Attitudes to Public Service Delivery by the Voluntary and Community Sector in the North West of England. Manchester: Centre for Local Governance, University of Manchester.

Rees, J., Macmillan, R., Dayson, C., Damm, C., & Bynner, C. (Eds.). (2022). COVID-19 and the Voluntary and Community Sector in the UK: Responses, Impacts and Adaptation. Policy Press. CrossRef link

Rees, J., Taylor, R., & Damm, C. (2024). Opening the ‘black box’: Organisational Adaptation and Resistance to institutional isomorphism in a prime-led employment services programme. Public Policy and Administration, 39(1), 106-124. CrossRef link

Rees, J., Whitworth, A., & Carter, E. (2015). Support for All in the UK Work Programme? Differential Payments, Same Old Problem. In M. Considine and S. O’Sullivan (eds), Contracting-out Welfare Services. CrossRef link

Sanderson, M., Allen, P., Gill, R., & Garnett, E. (2018). New models of contracting in the public sector: A review of alliance contracting, prime contracting and outcome‐based contracting literature. Social Policy & Administration, 52(5), 1060-1083. CrossRef link

Smerdon, M. (ed.). (2009). The First Principle of Voluntary Action: Essays on the Independence of the Voluntary Sector from Government in Canada, England, Germany, Northern Ireland, Scotland, United States of America and Wales. London, Baring Foundation.

Taylor, R., Rees, J., & Damm, C. (2016). UK employment services: understanding provider strategies in a dynamic strategic action field. Policy & Politics, 44(2), 253-267. CrossRef link

Wells, P. (2011). Prospects for a big society? People Place and Policy Online, 5(2), 50-54. CrossRef link

Wells, P. (2012). Understanding social investment policy: evidence from the evaluation of Futurebuilders in England. Voluntary Sector Review, 3(2), 157-177. CrossRef link