Abstract

Concerns about a minority of families have resurfaced in social policy at key moments throughout recent history. Whether these families are viewed as having ‘needs’ or ‘problems’; and whether they are seen as primarily ‘troubled’ or ‘troublesome’ shifts and changes along with the solutions put forward. This article considers the ‘Troubled Families Programme’ (TFP) in England as a contemporary response. It draws on research commissioned by a city local authority concerned with profiling key aspects of the needs of 103 families worked with in the early part of the first phase of the TFP. While research and policy have frequently underlined the multiple needs and high level of service involvement characteristic of these families, remarkably little is known about the lived experience of multiply disadvantaged families and the wider context of their lives. In this paper, we place the 103 families’ circumstances within a temporal context by presenting unique historical data on their service involvement. We focus in particular on families’ contact histories with Children’s Social Care. The research presented in the article reveals an extraordinarily high level of involvement with social services across generations among the families referred to the TFP. The article argues that there is a need to better understand families’ pathways through the life course and outwith immediate referral criteria. It also raises important questions about the respective roles for the TFP and social workers.

Introduction

Concerns about a minority of ‘problem’ families have a long history and resurface in social policy at key political moments. The way in which families are characterised and solutions put forward varies according to the wider contexts within which they are embedded (Cairney, 2019; Crossley, 2018). This has led to a range of policy developments, including family intervention projects (FIPs) and the Troubled Families Programme (TFP) designed to address multiple and complex needs through whole-family, multi-agency working.

The TFP only operates in England, other countries of the UK have a different approach to families with multiple needs. It was devised on a Payment by Results model, with local authorities (LAs) paid an attachment fee for each ‘troubled family’ they worked with, and a further allocation of funding dependent on certain outcomes being met. The primary target groups were highly specific – families with co-occurring problems of household welfare reliance; school exclusion, truancy and persistent school absence; youth convictions or youth and/or adult anti-social behaviour; and being in receipt of out of work benefits (DCLG, 2012a). The expansion of the programme to include another 400,000 families (about 6.6 per cent of all families) was announced very quickly (HM Treasury, 2013) and the second phase of the TFP was started early in 2015 in some LAs (ahead of the national evaluation and any independent evidence about outcomes). The funding per family for phase two was halved but the remit was expanded to include younger children, families in debt, drug and alcohol misuse, domestic violence, and mental and physical health problems (DCLG, 2015). Central to the TFP has been the idea that a single point of professional co-ordination and contact within a ‘whole family approach’ will be a better experience for families that should lead to less need for high cost services, such as care and custody.

Research and policy narratives have frequently underlined the multiple adversities of families referred to the TFP, together with the high level of service involvement these families have prior to their engagement with a TFP. Yet, despite such assertions, remarkably little is actually known about the lived experiences and pathways across the life course of families referred to the TFP. It has been argued that there is a need for more research that better understands ‘troubled’ families within their wider context, spatially and temporarily (Jupp, 2017). This article makes a contribution to this ambition by providing important quantitative evidence on service involvement. Drawing on key service data in relation to 449 individuals from 103 families, the article illuminates the extraordinarily high level of social care contacts among families referred to the TFP in one local authority area. It presents unique historical data that illustrates the depth and range of needs, and the long history of social services involvement in most cases. In so doing, the data highlights the extent of the significant overlap between TFP and Children’s Social Care (CSC) populations, and with that the nature and extent of the needs of the family. This also prompts debate about the relationship between social care and the TFP (Davies, 2015).

The paper begins by providing an overview of the TFP, drawing particular attention to its relationship with social services. It goes on to present findings from the study concerned with better understanding the histories of key service involvement of a sample of families referred to a TFP. It draws on research commissioned by a city local authority that profiled key aspects of the needs of 103 families worked with in the early part of the first phase of the TFP. In the final section of the article we discuss the questions that the findings raise and highlight what implications the data has for a future research agenda. We repeat calls for more research into the lived experiences of families including longitudinal or biographical research into the pathways between childhood and adult experiences (Spratt, 2011).

Multiple needs and the TFP

The Coalition-government (2010-2015) brought together a number of familial adversities under the umbrella term ‘Troubled Families’ when it launched the TFP in late 2011 as a way of responding to a range of inter-connected and persistent family-based welfare problems. The first phase (2012-15) of the TFP in England started with the premise that a small number of families (120,000 or nearly two per cent of families) have multiple problems but also cause significant problems; and, that in turn they cost the taxpayer an estimated £9 billion a year, or an average of £75,000 per family (DCLG, 2014).

The 2011 riots in English cities were an important part of the initial political context for the TFP represented by (then Prime Minister) David Cameron (2011) as symptomatic of a moral collapse within a ‘Broken Society’. The latter was given definition within a narrative of blame and individual deficit that drew heavily on an underclass discourse. The (then) Department for Communities and Local Government (DGLG) (2014: 11) later characterisation of ‘troubled families’ as having ‘multiple and layered problems’ did recognise that some problems are a manifestation or consequence of another – such as behavioural problems in school or poor school attendance when children have witnessed domestic violence. Similarly, in her personal ‘research’ study Listening to Troubled Families, Louise Casey (DCLGb: 2012) suggested that the most striking common themes across the families she interviewed were: a history of sexual and physical abuse, inter-generational transmission of problems, time spent in the care system, having children at a young age, violent relationships, children with behavioural problems ‘leading to exclusion from school, anti-social behaviour and crime’ (DCLG, 2012b: 1). The government narrative however both overstates some problems and potential connections, and overlooks other crucial structural issues entirely, such as being out of work, relative poverty as well as poor health. The potential for stigmatising is also apparent from both the decision to characterise families as ‘troubled’, yet focus on ‘troublesome’ behaviour to the neglect of other issues, circumstances and needs (Wenham, 2017; Levitas, 2012).

Whether the problems families face are primarily understood to be a result of social and economic disadvantage and marginalisation; or, fecklessness and irresponsibility, is a long running debate (Welshman, 2008). Yet notwithstanding the controversy and disparity around definitions of ‘multiple adversities’ (Bunting et al, 2015), there is wide ranging evidence both about the proportion of households in the UK who have multiple needs associated with disadvantage and the negative impact of adversity. For example, the Social Justice Strategy acknowledged that 11 per cent of adults (5.3 million people) in the UK experience three or more of six broad areas of ‘disadvantage’ at any one time. These include: education, health, employment, income, social support, housing and local environment (DWP, 2012: 8). Academic research evidence also suggests that it is the number of problems or issues present in families that is predictive of poor outcomes (Feinstein and Sabates, 2006; Spratt, 2012).

Within the prevailing discourse, families referred for intensive support are not only characterised as having multiple and inter-related support needs, but needs that have not been adequately addressed by other agencies. The TFP is rationalised, in part, therefore as a response to the inability of agencies to support these families: “…public services have previously failed families who have multiple problems because they operate in a siloed and mostly reactive fashion” (MHCLG, 2017a: 10). Although reference is often made to the long documented problems of coordination across agencies, the policy rhetoric commonly places the emphasis not on the failing of state and non-state agencies but as a failure of families’ ability or willingness to engage with welfare agencies and previous state interventions: “they are difficult to deal with” (Respect Taskforce, 2006: 22; Crossley, 2018; Bond-Taylor, 2015; Parr and Nixon, 2009).

As a response to the ‘problems’ presented by families with multiple needs, the TFP represents a non-statutory intervention that is often institutionally located within specific services such as FIPs (run by the statutory or independent sector), although in some locations mainstreamed as the main mechanism for delivering services to the most vulnerable children and families (Batty et al., 2013; Day et al., 2016). Phase one of the TFP was essentially focussed in Tier 3 services in England (see SCIE, 2012), that is referred services such as social services and child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS). They were originally positioned below the threshold criteria for social services involvement and child protection concerns which were not part of the initial focus. Families were asked to sign up to the programme, rather than being told that they must accept the help. However, such families could also be facing other types of more coercive response at the same time, such as a threat of eviction because of rent arrears or prosecution because of persistent absence from school. As such, signing up to the programme was not totally voluntary nor totally coercive, despite some of the tough talking from politicians early on in the programme (Bond-Taylor, 2014). The semi-voluntary nature of the programme is both an advantage of the TFP but also an inherent tension (Parr, 2011). For example, child welfare concerns are likely to be present in many (probably most) of the households and statutory services (such as social services) may have to become involved. Hence, in part, the TFP represents another way of delivering state services to complex families with multiple problems that may initially bypass social services and other types of statutory intervention.

Evaluative studies of the TFP (and FIPs before them) have provided qualitative and quantitative evidence on the prevalence of family problems (usually in the 12 month period) before and at the point of referral, including levels of service contact (e.g. Day et al., 2016; White et al., 2008). Further, there is now a large and growing body of work that has sought to critically examine the role of the TFP in supporting multiply disadvantaged families (Crossley, 2018; Davies et al, 2015; Hayden and Jenkins, 2014; Parr, 2011). Within these studies, there has been some attempts to understand multiple adversities from the accounts of families (Wills et al, 2017; Bond-Taylor, 2016; Bunting et al, 2015); better understand families multiple needs (Boddy et al., 2016); as well as their experiences of multiple service use (Morris, 2013). However, to date, our understanding of the complex realities of families’ lives including their contact and relationships with state agencies and interventions and, in turn, the nature of their support needs has been limited (Jupp, 2017). Indeed, the large majority of scholarly work on ‘the family’ has tended to focus on ‘ordinary’ families and, by contrast, there is limited research that focuses on those that are highly vulnerable (Morris, 2013; Wilson et al., 2012). This article provides important quantitative evidence to this emergent and necessary area of research focusing in particular on social care involvement. While the national evaluation of the second phase of the TFP (MHCLG, 2018) is one of the few studies that has collected data about child safeguarding problems in families referred to the TFP, the data reported in this article goes much further. In what follows, we present findings from a study that interrogated CSC data in considerably more depth looking not just at the number of families that have had involvement with CSC and the nature of that involvement but charting the number of referrals for each family. It presents a detailed examination of the histories and extent of families’ social work involvement, and in so doing gives a unique insight into the needs of the most disadvantaged families.

Researching a local TFP

The data in the article are drawn from a LA funded research project which concluded in 2015. The LA area has a total population of over 200,000; of whom approximately 46,000 are aged 0-19. The population is predominantly White; Black and Minority Ethnic groups make up about 11 per cent of the whole population; and, 14 per cent of children and young people. There are about 86,000 households and 30,000 contain only one person. The city is in the top 100 most deprived local authorities in England and has pockets of severe deprivation. The city scores low (over 300, out of 354 districts, where 354 is the most deprived) on the composite index of child wellbeing developed by the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). The number of children taken into care or custody is between 60 and 70 per year. At any one time, well over 200 children are in care and up to 20 are in custody (under one per cent of all 0-19 year olds).

The overall aim of the research was to provide a statistical profile of the needs of a sample of families referred to the TFP and the history of their key service involvements before referral. This was achieved through an interrogation of the organisational records and administrative data of key LA services. Data analysed included: referral data to the local TFP and CAF (the Common Assessment Framework document) at the time of referral; as well as historical searches on records relating to CSC involvement; educational problems and needs; and, youth offending history. The research was intended to provide insight and understanding about the complexity and intensity of the support needs of families. The research was not concerned with evaluating the TFP service.

The purpose of the research was explained to the families by their TFP support worker and the families gave their informed (signed) consent for the researchers to have access to their data. The research was ethically reviewed by the University of Portsmouth. Gaining signed informed consent from families and then verifying information about family members was a time-consuming process. However, once data on family members was verified with the family’s key worker, historical searches (focussed on social services involvement, youth offending and educational issues within the families) was undertaken by staff within the LA. Data on each family/family member was then passed to the research team who compiled a dataset for further interrogation and analysis.

103 families gave their consent to take part in the research. The 103 families had been referred to the TFP between 2012 and 2014 and represented nearly a fifth of the original target (550 families) for the city. The sample comprised 449 individual family members. In addition, a purposive sample of ten of these families were chosen in order to move beyond statistical profiles of the families and provide further insight into the dynamic and complex issues within individual cases.

The following section reports on key findings from the research, focusing on the nature of CSC involvement with the families. This is supplemented by illustrative evidence from case files. The article then opens up the discussion about what this data might tell us about the needs of TFP families.

Profiling the TFP Families

Multiple Needs

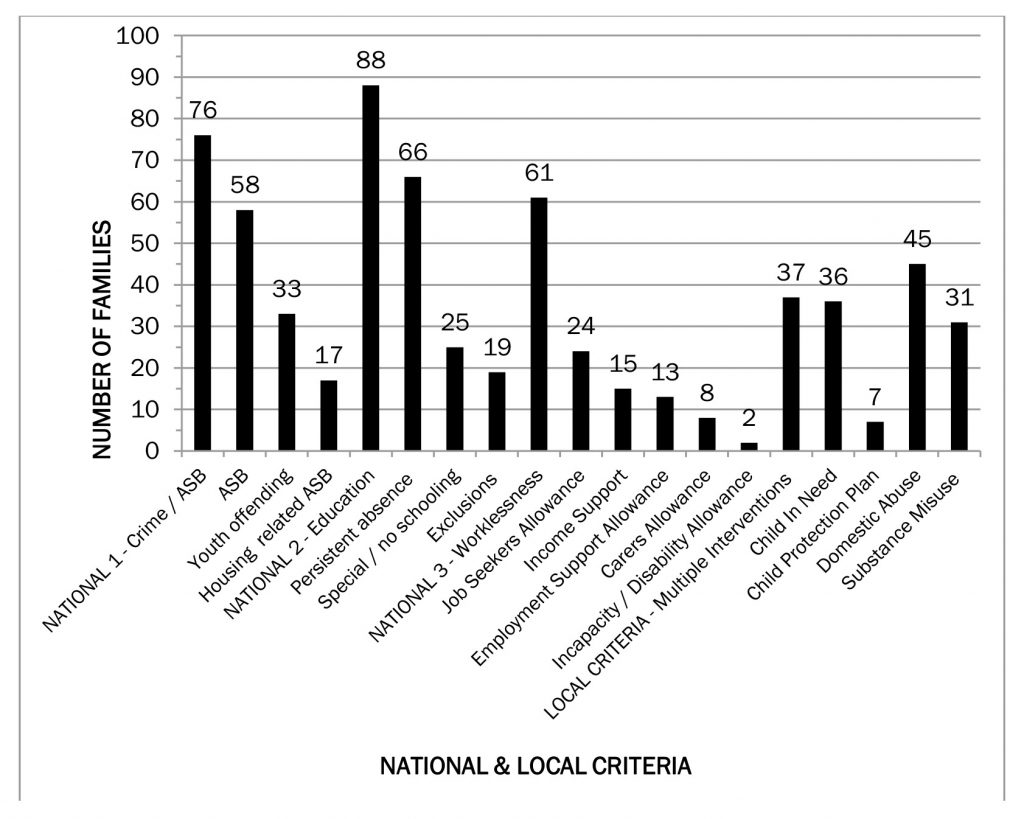

We begin by providing a broad overview of the families and the level of identified need at the point of referral. Although the configuration of multiple and layered problems is specific to each household, the research revealed commonalities across the families. Figure 1 illustrates that some combination of educational need (indicated by persistent absence, special educational need or exclusion from school) was the most common issue across all families (88, 85.4 per cent). This is not surprising as it was one of the national criteria for referral in Phase One. The second most common issue was involvement is crime or anti-social behaviour (76, 73.8 per cent); again this is one of the national criteria. Worklessness, similarly one of the national criteria, was an issue in nearly six in ten families (61, 59.2 per cent). A range of other issues were highlighted by the local referral criteria for the TFP: domestic abuse (45, 43.7 per cent); multiple interventions apparent in the family without any sustained change (37, 35.9 per cent); one or more of the children known to be a ‘child in need’ (36, 34.9 per cent) and substance misuse within the family (31, 30.1 per cent). These latter issues are all national criteria in phase two of the TFP. In a minority of cases the child was already on a Child Protection Plan (CPP) (7, 6.7 per cent) when referred to the TFP.

The ten case studies illustrated other major issues and needs that were not covered by either the national or local criteria for the TFP. It cannot be over-emphasised just how many adversities these families faced. The quotes from case files below provide an indication of how the issues in Figure 1 intersect with others, such as bereavement, sexual abuse, young carers, child to parent violence, poor home conditions and so on. Physical and/or mental health issues were a common feature of case studies, as was significant loss within the family, such as the death of two children in the following case:

“…the family have suffered a traumatic loss in the death of two of the [children]. This is said to have impacted on the family and especially [the mother] who was diagnosed with abnormal grief reaction……….This has, in part, impacted on the family and a caring role for [the 13-year old daughter]. [The mother] has disclosed a history of violence from [current husband]. [She] has stated that she would not call the police as she does not want the further embarrassment of having them involved with her family….”

Trauma, such as sexual abuse, was associated with mental health problems and child to parent violence in another case:

“[the child] still struggles with sleeping with the light off. He has to have the door shut and hear it click and he does not like his TV turned off….. [he] has huge anxiety around bed time. This can often result in [the child] having a panic attack and making himself sick…..Mum worries about [the child’s] temper. She explained that he swears at her and he hits out at her. She informs us that his temper is terrible and he snaps quickly. Mum added that [the child] has shown aggression to her and to his Nan.”

Other issues included children who were regularly reported missing to the police and poor home conditions. In one case, this included no access to hot water, resulting in a teenage girl avoiding school:

“Some of the unauthorised absences are in relation to [her] being home alone and not wanting to attend school as she could not have a bath…….The parents both work and leave the property at 5.30am and the younger siblings are left in the care of the eldest sibling……The family report that they have trouble with the heating and the landlord has been advised ……The family wish to move but housing options have told them they cannot be moved until the arrears are cleared.”

Families’ contacts with children’s social care

The paper is particularly concerned with drawing attention to the findings regarding families’ historical contact with CSC, which was striking. Of those families that we collated data on, a history of social services involvement was the most common factor. The data revealed that all but five families (95.1 per cent, 98) referred to the local TFP were ‘known to’ CSC, that is there was a record of at least one referral. Only four of the 98 families had a referral with no further action. In most cases, families were referred to CSC before they were referred to the local TFP (92.2 per cent of all families, 95 of the 98 families known to CSC). The three additional families became known to CSC after referral to the local TFP.

Families had different levels of support and involvement from CSC. All but four referrals were accepted (94 of 98) but many families (41.7 per cent, 43) were assessed only. However, over a third (35.9 per cent, 37) of the families had at least one child who had been the subject of a Child Protection Plan (CPP) and over a quarter (28.2 per cent, 29) had at least one child who had been ‘looked after’ (LAC). This compares to the national evaluation in which 8.0 per cent of children (within matched comparison groups) had been on a CPP and 1.6 per cent were ‘looked after’ (MHCLG, 2017b). The striking difference in our study is most likely explained by the fact that our study includes historical data on families; that is it includes whether a family has ever been on a CPP or LAC, compared with the national evaluation of phase two which focuses on the situation within the year before the intervention. Of course our data may also be indicative of local referral practices, models of multi-agency working and/or higher numbers of families with child safeguarding issues in the city. On the other hand only a small number of families (six cases or 5.8 per cent) were open to CSC during the local TFP intervention, a percentage comparable with the national evaluation. However, it was the amount of referrals to CSC for these families that was most striking: the mean number of referrals was 11.14 taking place before the family were worked with on the local TFP and 12.09 referrals including the additional referrals during and after TFP involvement.

Of particular note, given the positioning of the TFP nationally below Tier 4 specialist residential services (such as care and custody), is the number of families who had already had a child ‘looked after’ and returned home before referral (11.7 per cent, 12) and those who had started to be looked after (26.2 per cent, 27) before they were referred to the service. In other words, over a quarter of the families already had at least one child who had previously or started being looked after (a Tier 4 service) before referral to the local TFP (a Tier 3 service). The mean age of children at the time of the first referral to CSC was nearly seven years old (6.98) but it took until nearly age ten (9.57) before a referral was accepted, on average.

We were able to undertake further historical analysis into parent contact with CSC for all referrals (not just the current family’s first contact). Again, this represents a unique insight into intergenerational contact with CSC. The data illustrated that in well over a third (38.8 per cent; 38 of 98) of families, a parent had also been referred to CSC as a child. This includes any male or female parental figure such as step parents. Half of these referrals of the parents’ generation were not accepted. Of the referrals accepted (20.2 per cent, 19 of 98), eight families had a parent who had been looked after as a child and four families had a parent who had been on a Child Protection Plan (CPP) as a child.

The ten case studies illustrated in more depth the complex interplay between the role of CSC and the TFP, as well as the concerns raised by schools and the police. All ten cases had CSC involvement, mostly this was clearly some time before the TFP referral. For example, a fifteen year old girl who had left her foster placement was referred to the TFP because she had expressed concerns for her own safety:

“….her stepfather ….. was physically and verbally abusive towards her mother and [she] reports he has punched her mother. [she] also disclosed that her mother was using cannabis on a daily basis and her stepfather was also misusing alcohol on a regular basis. [she] reported to me that she feels that her mother and [stepfather] place their needs before hers. [she] feels that all the income for the household is spent on cannabis and alcohol.”

There appears to be a long history of concern in this latter case:

“[the child] has reported throughout her childhood to her school and her previous social worker that she has been unfed by her mother……..Throughout [her] childhood referrals have been received by the department [CSC] from each of the schools………They have detailed that [she] was coming to school looking unkempt and with untreated head lice.”

The specific behaviours of concern leading to this referral to the TFP included: running away, aggressive behaviour, theft and alcohol use in the park. In the past she had absconded from the school site and was involved in bullying situations (both as the bully and victim). There were a number of CYPRs (children and young person records) from the police including an incident when she absconded with her sister’s 27 year – old boyfriend, after he split up with her sister. Another record related to a police call out to her home where she had got into a physical altercation with her mother who had been drinking all day: her mother was arrested for common assault on the child. There was also evidence of self-harming.

Discussion

In this final section we reflect on what the data presented above tells us and how it might inform a future research agenda. In so doing, we are mindful of the limitations of the research. We are not in possession of more qualitative details of individual cases and an understanding of why re-referrals were made to CSC e.g. whether families are being over-referred or re-referred to CSC who shouldn’t be (Bentley et al., 2016; Bilson and Martin, 2016). Furthermore, the research did not involve an examination of the institutional relationships and strategic arrangements between the TFP and SCS in the city. We must therefore be mindful of what we are able to infer from these data and not over-interpreting the findings. Notwithstanding these caveats, the data presented here do provide valuable and unique insight into the intergenerational components of family adversity. What the current research illustrates with clarity is that there is a very high degree of overlap between families in the TFP and those worked with by CSC. There appears to be an unambiguous overlap between TFP and CSC populations, and by implication the nature and extent of the needs of the family. In this context therefore the TFP was not necessarily preventing the escalation of problems, it might be viewed rather as the latest in a series of interventions with families, over a third of whom had similar family problems in relation to the need for social work intervention in the previous generation. These data therefore appear to demonstrate a pattern of history repeating itself.

These data provide important evidence on the nature and extent of families’ historical contact with social services and thereby also provide some indication of the ongoing nature of adversity. The findings echo others work on the TFP which has pointed not only to the complexity and inter-related nature of families’ unmet needs but also the connections between parents’ and children’s needs and well-being, and historic and inter-generational patterns of adversity (Wenham, 2017; Boddy et al., 2016). Moreover, resonating too with studies that have demonstrated a mismatch between state conceptualisations of family ‘troubles’ when compared to the accounts and experiences of those subject to policy intervention (Wenham, 2017), this study provides valuable data that highlights the importance of considering more than just the recent history of family referrals. It is important to note, that acknowledging intergenerational aspects of adversity does not mean subscribing to behavioural understandings of intergenerational transmission of disadvantage such as in the notion of a ‘cycle of deprivation’ (Welshman, 2008) but rather the apparent longevity, complexity and chronicity of families needs. This necessitates recognition that positive change is not straightforward or easily achieved. Although the TFP discourse has moved on from ‘turning families around’ to achieving ‘significant and sustained progress or continuous employment’ (Bate and Bellis, 2018), a better understanding about the nature and extent of family needs enables us to think differently about inciting change within families and the kinds of (probably) long-term support that is required (Jupp, 2017). This in turn reaffirms calls for research that sees and understands families within their longer biographies, in part, to better recognise problems in families who are already known to social care (Spratt, 2011). Such research should seek to identify not just family ‘troubles’ and ‘risk’ but family resources, strengths and resilience, and to also place these within wider landscapes. Jupp (2017: 270) conceptualises this as research which traces “how families may move between problems, troubles, resolutions, coping and ‘normality’: both within cycles of the everyday and also over the life course”.

The data also raises questions about the relationship between the TFP and statutory services, in particular, where the TFP sits in relation to social work (Davies, 2015). The TFP represents an intervention by the state around a highly complex and dynamic set of issues associated with unmet need that is formally distinct from social work with families. This is despite the fact that work practises are very much located on the terrain previously occupied by various forms of family and community work that used to be part of the work of social services departments (Parton, 2014). Within this context, it has been suggested that the TFP might offer an opportunity for social work to reclaim some of its roots including a family orientation and that of relationship-based work (White et al., 2014; Parr, 2009). White et al. (2014) suggest that TFP initiatives might have something to offer in this respect:

“…The national Troubled Families payment-by-results initiative is offering unexpected opportunities for a new type of early help for families. The initiative also offers the possibility for a social work to re-establish a firmer footing in preventive and supportive work that nudges the thresholds of statutory services for children’s social care” (White et al., 2014: 85).

Brandon et al. (2015) also point out that the new occupational role of the family intervention key worker, brought about by the expansion of intensive family support services such as the TFP, potentially brings with it a new role for social workers, working alongside this new workforce. Jones (2015) makes a similar point arguing that multi-agency and inter-professional teams characteristic of troubled families services bring together the dual benefits of specialisation and integration. This greater integration may bring with it alternative responses and interventions to families that may be ‘at risk’ and have histories of social work contact (Bilson and Martin, 2016; English et al., 2000). Such families might be better served on a non-coercive, voluntary basis by the TFP and assessed not investigated (Platt and Turney, 2014). Of course there are also examples of early-intervention social work teams being used as a means to reduce the need for statutory social work intervention (Moran et al., 2007) and Thoburn et al. (2013) have summarised the common elements of successful social work and interdisciplinary services for families with complex difficulties. However, she also warns that:

“The ‘insulation’ at both the national level and in many authorities at the local level too, of the troubled families service from the child and family social work services, can only impede rational policy making about the best way to use limited resources to help the most vulnerable children and their families” (Thoburn, 2013: 475)

Data from the evaluation of the second phase of the TFP suggests that the TFP might be reducing demand on CSC (MHCLG, 2018), yet there is currently a lack of evidence however about the relationship between key working and social work and important questions remain unanswered. Case study research is required that explores how TFP key workers operate across different professional boundaries and the structures and processes that facilitate such patterns of inter-agency working. This work needs to identify examples of how social workers and key workers can work within productive partnerships to best meet the needs of families with complex needs.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented unique, historical data on contact with CSC among a sample of 449 individuals from 103 families referred to a TFP in one LA area. All but five families were known to CSC and the data presents a clear picture of long and complicated histories of CSC involvement. We suggest that these data alert us to a need for more research into the lived experiences of families with complex needs. This research should be informed by a longitudinal perspective in order to understand the extent of inter-generational, enduring and multiple factors. The large number of families referred to the TFP that have had some sort of CSC involvement also demands that we develop a better understanding of how the TFP key worker role is and should be positioned in relation to social work. Ensuring an alignment of the TFP with CSC is a current priority for the Government (MHCLG, 2017a) and it is imperative that the complexity of families’ needs are fully realised as part of this endeavour.

Dr Sadie Parr, CRESR, Sheffield Hallam University, Unit 10 Science Park, Howard Street, Sheffield, S1 1WB. Email: s.parr@shu.ac.uk

Batty, E., Crisp, R., Green, S., Platts-Fowler, D. and Robinson, D. (2013) Key Working and Whole Household Interventions in Sheffield: Key Lessons and Priorities for Action. Sheffield: CRESR/Sheffield City Council.

Bate, A. and Bellis, A. (2018) The Troubled Families Programme (England): Briefing Paper. London: Housing of Commons.

Bentley, H., O’Hagan, O., Raff, A. and Bhatti, I. (2016) How safe are our children? The most comprehensive overview of child protection in the UK. London: NSPCC.

Bilson, A. and Martin, K.E.C. (2016) Referrals and Child Protection in England: One in Five Children Referred to Children’s Services and One in Nineteen Investigated before the Age of Five. British Journal of Social Work, 47, 3, 793-811. CrossRef link

Boddy, J., Statham, J., Warwick, I., Hollingworth, K. and Spencer, G. (2016) What Kind of Trouble? Meeting the Health Needs of ‘Troubled Families’ through Intensive Family Support. Social Policy and Society, 15, 2, 275-288. CrossRef link

Bond-Taylor, S. (2016) Domestic surveillance and the Troubled Families Programme: understanding relationality and constraint in the homes of multiply disadvantaged families. People, Place and Policy, 10, 3, 207-224. CrossRef link

Bond-Taylor, S. (2015) Dimensions of Family Empowerment in Work with So-Called ‘Troubled’ Families. Social Policy and Society, 14, 3, 371–384. CrossRef link

Bond-Taylor, S. (2014) The politics of ‘anti-social’ behaviour within the Troubled Families programme. In: Anti-social behaviour in Britain: Victorian and contemporary perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 141-154. CrossRef link

Bunting, L., Webb, M. A. and Shannon, R. (2015) Looking again at troubled families: parents’ perspectives on multiple adversities. Child & Family Social Work, 22, S3, 31-40. CrossRef link

Cairney, P. (2019) The UK government’s imaginative use of evidence to make policy. British Politics, 14, 1, 1-22. CrossRef link

Cameron, D. (2011) David Cameron’s speech on plans to improve services for troubled families, December 15th. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/troubled-families-speech

Crossley, S. (2018) Troublemakers: the construction of ‘troubled families’ as a social problem. Bristol: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Davies, K. (2015) Social Work Practice with ‘Troubled Families’: A Critical Introduction. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Day, L., Bryson, C., White, C., Purdon, S., Bewley, H., Sala, L.K. and Portes, J. (2016) National Evaluation of the Troubled Families Programme. Final Synthesis Report. London: Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG).

DCLG (2015) Financial Framework for the Expanded Troubled Families Programme. London: Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG).

DCLG (2012a) The Troubled Families Programme. Financial framework for the Troubled Families programme’s payment-by-results scheme for local authorities. London: Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG).

DCLG (2012b) Listening to Troubled Families. London: Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG).

DCLG (2014) Helping Troubled Families Turn Their Lives Around. London: Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/policies/helping-troubled-families-turn-their-lives-around

English, D.J., Wingard, T., Marshall, D., Orme, M and Orme, A (2000) Alternative responses to child protective services: emerging issues and concerns. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24, 3, 375-388. CrossRef link

Feinstein, L. and Sabates, R. (2006) Predicting Adult Life Outcomes from Earlier Signals: Identifying Those at Risk. Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning. London: Institute of Education.

Felitti, V., Anda, R., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D., Spitz, A., Edwards, V., Koss, M. and Marks, J. (1998) Relationship of adult health status to childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 14, 245-58. CrossRef link

Hayden, H. and Jenkins, C. (2014) ‘Troubled Families’ Programme in England: ‘wicked problems’ and policy-based evidence. Policy Studies, 35, 6, 631-649. CrossRef link

HM Treasury (2013) Massive expansion of Troubled Families Programme announced, June 24th. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/massive-expansion-of-troubled-families-programme-announced

Jupp, E. (2017) Families, policy and place in times of austerity. Area, 49, 3, 266-272. CrossRef link

Levitas, R. (2012) There may be ‘trouble’ ahead: what we know about those 120,000 ‘troubled’ families. Policy Response Series No. 3. April. Bristol: University of Bristol.

MHCLG (2018) Supporting Disadvantaged Families: Annual Report of the Troubled Families Programme 2017-18. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG).

MHCLG (2017a) Supporting Disadvantaged Families: Troubled Families Programme 2015-2020: Progress So Far. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG).

MHCLG (2017b) Supporting Disadvantaged Families: Troubled Families Programme 2015-2020: Family Outcomes – national and local datasets. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG).

Moran, P., Jacobs, C., Bunn, A. and Bifulco, A. (2007) Multi–agency working: implications for an early–intervention social work team. Child and Family Social Work, 12, 2, 143–151. CrossRef link

Morris, K. (2012) Troubled families: vulnerable families’ experiences of multiple service use. Child and Family Social Work, 18, 2, 198–206. CrossRef link

NIESR (2016) NIESR Press Release – No evidence Troubled Families Programme had any significant impact on key objectives, NIESR evaluation finds. London: National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR). Available at: http://www.niesr.ac.uk/media/niesr-press-release-%E2%80%93-no-evidence-troubled-families-programme-had-any-significant-impact-key

Parr, S. (2011) Family policy and the governance of anti-social behaviour in the UK: women’s experiences of intensive family support. Journal of Social Policy, 40, 04, 717-737. CrossRef link

Parr, S. (2009) Family Intervention Projects: a site of social work practice. British Journal of Social Work, 39, 7, 1256-1273. CrossRef link

Parr, S. and Nixon, J. (2009) Family Intervention Projects: sites of subversion and resilience. In: Barnes, M. and Prior, D. (Eds) Subversive Citizens Power, Agency and Resistance in Public Services. Bristol: Policy Press. CrossRef link

Parton, N. (2014) The Politics of Child Protection: Contemporary Developments and Future Directions. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Platt, D. and Turney, D. (2014) Making Threshold Decisions in Child Protection: A Conceptual Analysis. British Journal of Social Work, 44, 6, 1472-1490. CrossRef link

SCIE (2012) The wider network: the ‘four-tier model’ of services. London: Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE). Available at: http://www.scie.org.uk/publications/introductionto/childrenssocialcare/furtherinformation.asp

Spratt, T. (2011) Families with multiple problems: Some challenges in identifying and providing services to those experiencing adversities across the life course. Journal of Social Work, 11, 4, 343–357. CrossRef link

Spratt, T. (2012) Why Multiples Matter: Reconceptualising the Population referred to Child and Family Social Workers. British Journal of Social Work, 42, 1574-1591. CrossRef link

Thoburn, J. (2013) Troubled families, troublesome families and the trouble with payment by results. Families, Relationships and Societies, 2, 3, 471-75. CrossRef link

Thoburn, J., Cooper, N., Brandon, M. and Connolly, S. (2013) The place of ‘think family’ approaches in child and family social work: Messages from a process evaluation of an English pathfinder service. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 228–236. CrossRef link

Welshman, J. (2008) The Cycle of Deprivation: Myths and Misconceptions. Children & Society, 22, 2, 75-85. CrossRef link

White, C., Warrener, M., Reeves, A. and LaValle, I. (2008) Family Intervention Projects: An evaluation of their design, set-up and early outcomes. London: Department for Children, Schools & Families.

White, S., Morris, K., Featherstone, B., Brandon, M. and Thoburn, J. (2014) Re-imagining early help: looking forward, looking back. In: M. Blyth (ed.) Moving on from Munro: Improving children’s services. Bristol: Policy Press.

Wills, J., Whittaker, A., Rickard, W. and Felix, C. (2017) Troubled, Troubling or in Trouble: The Stories of ‘Troubled Families’. The British Journal of Social Work, 47, 4, 989–1006. CrossRef link