Summary

This paper compares the increasing use of photography and other media arts within social research with participatory approaches to socially engaged documentary and art based photographic practice. Discussion draws on the author’s own experience as a photographer and filmmaker who has undertaken participatory documentation and research work in a range of different settings. This includes a recent project undertaken as part of a research programme commissioned by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which saw the author working alongside social scientists who were utilising a range of alternative and visual research methods.

In conclusion, it is suggested that convergence and crossover between these different, but increasingly related, practices is deserving of further study. A number of key issues are identified including: the detail of authorship; the influence of participant consent and related ethical concerns relating to engagement and outputs; the role and visibility of the facilitator; and the status of participatory art works as artefacts.

Introduction – Visual Research, Photography and Participation

Writing in 1974, Becker pointed to an historical relationship between photography and sociology and suggested that sociologists should study photography (Becker, 1974). By 1998, Harper observed that sociologists were taking inspiration from documentary photography and that, whilst documentary lacked ‘sociological frames or theories’, it offered a ‘more direct and critical sociology’ (Harper, 1998: 28). In recent years, alternative and visual research methods, often involving photography, have gained increasing, although not unchallenged, acceptance within the social sciences as valuable and credible techniques for collecting data. This interest is evidenced by a growing literature and range of publications on this topic. Such methods allow subjects to adopt the role of more active participants in the research process thus providing opportunities for more collaborative relationships between researchers and their subjects. Participatory photography would seem to offer visual sociologists an ideal opportunity to ‘see through the lenses of the cultural other’ something the postmodern critique demands (Harper, 1998: 34).

It is also becoming increasingly common for photographic practitioners to find themselves working alongside, or collaborating with, researchers on both the collection and dissemination of research in a range of settings. Whilst many of the methods utilised in these different but related practices are paralleled and the resulting images can often appear similar, there are important distinctions between the intent of the work and the context of both the production and dissemination of results. Whilst critique and discussion of these practices is present, to a greater or lesser extent, within their related literatures there is limited reflection across such practices.

This paper attempts to contribute a reflective account of these issues based on the author’s experiences of devising and delivering participatory arts and research projects for clients across a range of settings including arts, education, health, heritage, social care, regeneration and social research.

Visual Research and Photography

Writing in 2001, Marcus Banks suggests that although visual approaches to research are popular and accepted within his field of anthropology, imaged based research is more marginalised and undervalued within the social sciences. Prosser (1998), who explores and explains this marginalisation and ‘limited status’ in some detail, suggests that the root cause is ‘fragmentation’, with researchers who are working in similar ways divided by their different disciplines. This lack of a collective voice then limits the impact of visual researchers on orthodox qualitative research. Attempts have since been made to raise the status of visual research, draw together different approaches and methodologies and outline key issues and considerations in order to highlight the benefits of such methods. In ‘Introducing Visual Methods’, Prosser (2008) provides a useful contemporary overview of visual methods and suggests there has been a ‘sea change’ in methodology leading to increasing interest in ‘beyond text’ practices. He introduces the benefits of visual research as follows:

‘Simply put visual methods can: provide an alternative to the hegemony of a word and number based academy; slow down observation and encourage deeper and more effective reflection on all things visual and visualisable; and with it enhance our understanding of sensory embodiment and communication, and hence reflect more fully the diversity of human experience’ (Prosser, 2008: 4).

Often when methodologies are considered the focus is on a discussion of the role of photography produced or collected by the researcher and its use as data. A common application is the technique of ‘photo-elicitation’, where new or existing photographs are used to promote or extend discussion, and there is a range of literature exploring such uses. Although examples exist, especially from the field of health education in the work of Caroline Wang (Wang and Burris, 1994; Wang et al., 1996; Wang and Redwood-Jones, 2001), there is far less material examining art and media work generated by participants as part of the research process. What does exist tends to focus on the use of film and video rather than photography (Harper, 1998; Banks, 2001).

The collection of participant imagery (drawings, photographs or video), especially when accompanied by participant’s own voice or handwritten text expressing personal thoughts and concerns, has a directness that both personalises issues and engages the viewer and participatory work is often commissioned on this basis.

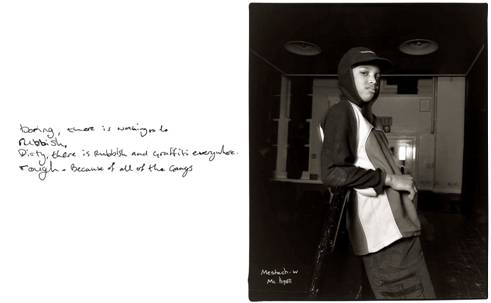

Figure 1: ‘Mesach’ from ‘Voices from The ‘Hood’, 2002 1

For ‘Voices From The ‘Hood’ I was commissioned by Gloucester Neighbourhood Renewal Team to facilitate photography and captioning projects with young people living in a deprived area of Gloucester. A key aim of the commission was to capture an authentic representation of young people’s views, in part to gather opinion, but also in support of a bid for urban renewal funding for the area. It was hoped that the project materials would personalise the issues relating to the bid through individual commentaries (Figure 1). There was also a desire to challenge people’s perceptions of young people as part of the problem, by giving them a voice in the process.

Such work, subjective by its very nature, deals with the specific and the personal rather than with the general and the shared. However, by doing so it can often capture the essence of a situation with a directness that both communicates effectively and imprints itself on the memory. The use of photography in a documentary or research context, however, raises important issues relating to photographic representation and the real that should be considered further.

Photography and the Real

For many commentators photography would seem to have a problematic relationship with its subject. The objective instrumentality of the camera combines with the subjective expression of the photographer leading to a complex treatment of reality. Photographs, on one hand, seem to be quotations from appearances (Berger and Mohr, 1982) or traces, footprints (Sontag, 1979) that somehow connect the viewer to their subject by a kind of umbilical cord (Barthes, 1981). Yet, on the other hand, they are fleeting, two dimensional moments cut from their place in space and time, edited and re-contextualised for display by subjective individuals.

Concerns regarding the indexical nature of the medium have tended to dominate photographic debate for much of the second half of the twentieth century (see ‘The Art Seminar’ in Elkinset al., 2007, pp. 130-155 for an interesting discussion of this). There is, however, a growing acceptance of a more complex relationship between viewer, photograph, photographer and subject. Derrick Price suggests that ‘We are no longer asked to accept that [documentary] images are impartial or disinterested; instead we inhabit a space between scepticism, pleasure and trust, from which we can read documentary images in more complex ways’ (Price, 2004: 101).

Whilst such concerns over photographs are now increasingly recognised, Becker reflects that many of the same problems faced by photography also exist within the social sciences in general and suggests that ‘none of the commonly accepted and widely used sociological methods solves them very well’ (Becker, 1994: 11). Researchers carefully frame interviews, compose their questions, transcribe and edit their responses, code the resultant data and select suitable quotes to illustrate their findings. However, this subjective processing and treatment of material is all accepted practice and undertaken within an established qualitative framework.

The apparent reluctance within the social sciences to accept photographs and other visual research material as valid data may be due to the subjective nature of its production and collection; its lack of scientific objectivity. Becker (1994) (after Stasz, 1979) suggests that at the beginnings of the science of sociology visual materials and photography were perhaps seen as ‘unscientific’ due to their association with early social reform work that was both crusading and ‘mud-raking’ rather than objective and neutral in character. Interestingly, this is in contrast to the general view of photography within the arts at the time, where it was often excluded or derided for being a mechanical, objective depiction of reality.

Despite this underlying reluctance, photographic, visual and other ‘alternative’ research methods are increasingly being used to support or extend conventional research methods. As such approaches gain currency, photographers, filmmakers and other media artists may find themselves commissioned to complement research teams bringing skills from their own practice to enrich research. It may thus prove useful to consider relevant trends within documentary photography in relation to visual research.

Participation and Documentary Photography

It is possible to see the development of a range of alternate approaches towards documentary photographic practice since the 1970s, including subject participation, as both a general move away from modernist photographic practice and its tendency to accept the evidential nature of the medium, and a direct response to the critical issues related to the indexicality of the medium that were (and in many ways still are) being debated by theorists and critics (see Sontag, 1979; Rosler, 1989; Elkins et al., 2007). These developments often explore or critique the photographer’s relationship with their subject and can involve elements of participation resulting in work quite similar in some respects to visual research materials.

Some documentary photographers chose to immerse themselves in projects whereby they come to know their subjects and subject matter over a number of years, producing informed, long term bodies of work (Davidson, 1970; Holt, 1985; Goldberg, 1995). Others turn towards documentation of their own lives, thereby negating accusations of exploitation and authenticity (Clarke, 1971, 1983; Goldin, 1986; Billingham, 1996) or acknowledge their subjective role in the process by including themselves within their images or reflecting on their role (Sultan, 1992).

Another strategy has been to invite participation, whereby some degree of control and thus power and ownership is handed over to the subject, whether in terms of making images or captioning them. In ‘Rich and Poor’, American photographer Jim Goldberg documents people at opposite ends of the social spectrum in their homes including a handwritten, reflective comment from the subject beneath each image. The resulting combination of image and text both creates a sense of authenticity and, to some extent, reveals the photographic process (Goldberg, 1985). Documentary practitioners with an agenda of social reform have frequently turned towards participatory photography for both gathering material and communicating the conditions and experiences of those with limited means or access to the media.

‘Shooting Back’, an ongoing participatory photography project founded by documentary photographer Jim Hubbard, has undertaken participatory projects initially in the USA and subsequently in other countries since the early 1990s (Hubbard, 1991, 2007). Functioning somewhere between documentary photography, journalism and social activism, this work has given voice to marginalised groups and both inspired and trained others to do the same. Such a participatory or collaborative approaches, which give voice to their participants, would seem to go some way to addressing the concerns regarding the authenticity of documentary material and practitioners often cite such reasons for utilising participatory techniques.

In a commission for the Lowry gallery I worked with children from the three primary schools in the area of Salford immediately adjacent to the multi-million pound docklands development where the new gallery was located. The aim of the project was to give the children and their families from this deprived inner city area a visual presence within the gallery and to convey to the gallery visitors (and staff) both the strength of their community and the hardships they faced (Figure 2).

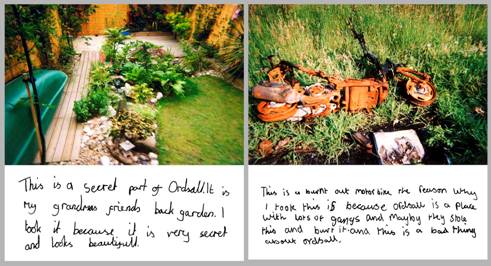

Figure 2: Images from ‘Ordsall A-Z’ 2000

Two images photographed and captioned by a 10-year-old participant on the ‘Ordsall A-Z’ project to demonstrate their likes and dislikes about their neighbourhood through contrasting spaces.

Captioned images were produced by more than 70 children and a selection, including at least one image from each participant, was exhibited at the official opening of the gallery. The project gave the children, their teachers (and indirectly their families) a voice and a presence within the Gallery and revealed aspects of the lives of those who lived in its shadow. Whilst this visual presence only lasted for the three months that the work was on display, the project did succeed in creating lasting links between the three schools and the gallery.

As well as giving voice to participants, projects can help provide alternative views of familiar documentary subjects and challenge traditional aesthetics and practices. Between 1995 and 2002 participatory photography projects were undertaken with street children in the Flavela do Morro do Cascalho in Belo Horizonte, Brazil by photographer Julian Germain, artist Patricia Azevedo and graphic designer Murilo Godoy. In their introduction to the resulting book ‘No Mundo Maravilhoso Do Futebol’ (1998) the artists clearly outline their motives for the project as a reaction against the ‘narrow and clichéd view’ of the traditional reportage photography for which the shantytowns of South America are a typical subject. The traditional approach is seen as being limited ‘both aesthetically and in the way it portrays people and their circumstances’. Conversely the children’s approach is described as ‘direct, curious, candid, unpretentious and honest’ as they ‘were not restrained by conventional notions of what makes a good picture’ (Germain, 1998). Eugenie Dolberg’s project ‘Open Shutters Iraq’ explores the impact of the allied occupation of Iraq on everyday life from the viewpoint of Iraqi women. Dolberg devised the participatory photography project in response to her frustration with the dominance of military and government sources in the media coverage of Iraq along with the difficulty of working there as a journalist. In addition, she questioned the prioritising of a foreigner’s external journalistic view over those of the local inhabitants (Dolberg, 2010).

Participatory projects can also be designed to address other parallel issues such as health, education and social wellbeing. Personal Expressions was a participatory photography project that grew out of a health study of young people in rural farming areas of Derbyshire in the wake of foot and mouth and BSE (Figure 3). Initially designed as an exercise in social wellbeing, the project developed to use photography as a means of empowerment and expression. Working with other photographers, I helped deliver participatory photographic activities to more than 100 young farmers across the Peak District. Many participants were initially sceptical as they felt no one was interested in their plight believing that they were being ignored by politicians of all persuasions and portrayed negatively in the media. A key desire and motivating factor was to have their voices clearly heard. The resulting exhibition toured nationally and was shown at the offices of the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs in London and in the Houses of Parliament (Syson-Nibbs and Robinson, 2009).

A number of common aims and intended benefits related to participatory arts work, within both photographic and research practice, can thus be identified and summarized as follows. Participation aims to directly capture subject voice and opinion and to offer the viewer the chance to experience the world through the eyes of a different individual or group directly involved in the issues concerned. This, it is hoped, will engage the viewer at a deeper, more personal, emotive or memorable level whilst also empowering and giving voice to subjects. Often such techniques are used in an attempt to capture the views of those that conventional techniques might overlook or exclude – marginal or hard to reach groups. Participatory activities can also help to engage subjects in parallel processes such as social, health and education and can encourage reflective discourse. Subject voice and imagery can also both illustrate and authenticate or test related research or journalistic work and prove useful in securing wider dissemination across different media.

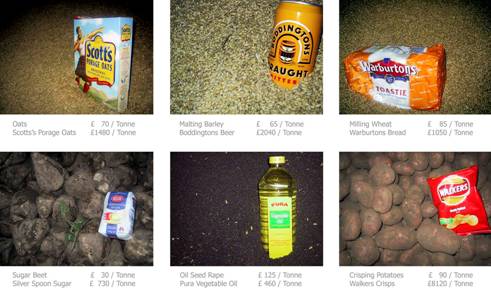

Figure 3: ‘Comparative Costs’ by Paul Spray 2007

Participant artwork produced as part of the ‘Personal Expressions’ a three year project originated by REAP (Rural Education and Arts Projects) and Bakewell Primary Care Trust.

Living Through Change: Visual Methods and Participatory Artwork – a Case Study

A recent three-year project commissioned by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation involved the author working alongside social researchers at the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research (CRESR) at Sheffield Hallam University on a major longitudinal study of the relationship between poverty and place entitled ‘Living Through Change: Life in Challenging Communities’ (CRESR, 2011). The research studied the experiences of residents in six UK neighbourhoods and utilised a range of techniques to collect information including formal qualitative interviews and alternative research methods (photography, photo elicitation and diary keeping) facilitated by the research team and a number of stand-alone participatory arts projects devised and delivered by the author.

The Living Through Change (LTC) project promoted the employment of qualitative methods and emphasised the need for an innovative and original approach to research and dissemination. In response, the project team sought to offer community members an active role in the research process. This involved researchers framing the research but also giving space for subjects to speak for themselves and develop personal narratives relating to key concerns. The inclusion of participatory arts and alternative research methods was seen to offer a range of opportunities for increased engagement (Robinson, 2009a).

The resulting participatory arts projects had two distinct aims: to increase engagement and to extend dissemination. It was hoped that the participatory arts projects would give those who took part a greater sense of involvement, empowerment and ownership and create active rather than passive subjects. Additionally, it was hoped that using a range of participatory methods would engage and capture the views of sections of the community that formal research methods might struggle to reach. Such activities were also intended to provide visible outputs that would help with efforts to feedback findings to the case study communities, as well as allowing dissemination via different media and technologies and thereby broadening the audience for the research.

Ultimately, participatory activity involved a mix of resident photography and captioning, audio interviews and filmmaking, audio and photo walks along with contributions of existing imagery and ephemera. Captioning projects were undertaken with a range of residents across four of the six areas resulting in local exhibitions, posters and short films. Feature length films were produced and publicly screened in two of the areas while short issue based films were created in the other four areas. Material was then reworked and disseminated via both the JRF and CRESR websites before a book and an exhibition of a representative selection of the artwork was created and exhibited in London (Figure 4) before touring to each of the communities concerned.

Figure 4: ‘Communities Under Pressure’ 2011

Installation views of the ‘Communities Under Pressure’ exhibition at New London Architecture, 26 Store Street, London, WC1E 7BT. June 2011.

On reviewing visual materials produced on the LTC project the artist and researchers commented on how the captioned images collected as part of the participatory arts projects closely resembled the captioned images produced by the research team as part of the formal research (Figures 5 and 6). However, although at first sight there appears to be strong similarities, when the context of production and use are considered, along with the intentions of those involved, major differences are also apparent.2

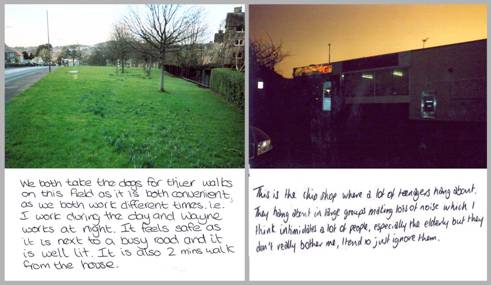

Figure 5: Resident images from Oxgangs, Edinburgh

Captioned images created by residents of Oxgangs that were used to elicit information in interviews as part of the formal research on the ‘Living Through Change’ project.

The intention of the researchers who utilised photography as a research tool was to further engage people who were already involved as interviewees and diary keepers. Disposable cameras were given to a number of interviewees who were asked to use them as an extension of their project diaries. Cameras were returned by post and the resulting photographs edited and captioned by the participants as part of subsequent interviews. For the researchers the photographs and their captioning provided an opportunity to elicit more information than might otherwise be obtained and also allowed the participants to actively engage and drive the discussion rather than to passively answer questions. One of the researchers who conducted the photo-elicitation sessions, reflected that the camera and diary projects also gave participants a greater sense of engagement or ‘buy in’ with the project and helped sustain their interest over different phases of interviews that took place over three years. The research photographs were not used in the final project report although some of the diary text was used in the reports and a book of diary excerpts was included in the final exhibition.

Conversely, the participatory arts projects, whilst related to the formal research, were driven by a different need; to produce creative material for exhibition, public screening or some other form of local output and wider dissemination alongside the final reports. The projects largely recruited their own participants who otherwise might not have been engaged by the project and although those who took part fully realised that their work would contribute to the LTC research, in most cases this was not the motivating factor behind their engagement. They engaged in part to have their voice heard (both locally and in a wider national context), in part to see their work on display and in part for something to do. Feeling ignored and overlooked was a key motivating factor in all the study areas.

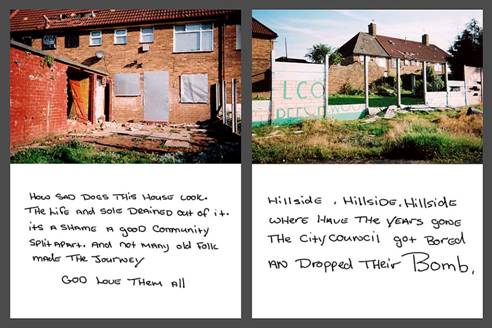

Figure 6: Hillside Estate, Huyton, Knowsley

Captioned images produced by a local resident as part of a ‘Living Through Change’ participatory arts project on the Hillside estate. These images were exhibited locally and then included in on-line material and the final touring exhibition.

The films that the artist produced in Amlwch, Anglesey (Robinson, 2009b) and West Kensington, London involved the collection of raw data in the form of audio and video interviews, a similar technique to that employed in the formal research where interviews were recorded before being transcribed. A key difference here, however, was that the making of the film was driven by the engagement and suggestions of local people and its content determined by the issues that the people themselves raised. In contrast, the formal research interviews, whilst open ended and qualitative, nevertheless explored a predetermined set of questions and themes.

Figure 7: ‘Lucky to Have a Job Here’ 2008

A visual narrative from Amlwch, Anglesey, North Wales, using imagery and interview text from a participatory film created as part of the ‘Living Through Change’ project.

At the same time that the Amlwch footage was being edited and sequenced by the artist, the research team were coding Amlwch interview data into a research database. Both artist and researchers commented on similarities between these processes. Raw film and interview data were initially edited to remove irrelevant material before the remaining content was broken into questions and responses that were then further subdivided into thematically coherent sections (research in the form of quotes and film material in the form of clips). The film was then constructed from the resulting ‘coded’ clips allowing the discussion of similar issues by different participants to be combined in sequence (Figure 7), a process to some extent paralleled in the data processing and report writing.

It is also interesting to note that in almost all cases the independent participatory arts projects identified and explored the same themes and issues as the formal research within the communities concerned. In some of the study areas the artist was aware of emerging issues from the formal research and it is possible that this might have subconsciously guided the work. However, in other areas this was certainly not the case as work either took place contemporaneously with the formal research or the issues were clearly identified and asserted by participants themselves. To this extent, the participatory projects were successful in testing and triangulating the project team’s findings. In addition, the participatory projects in some cases brought to light issues not captured by the formal research or provided greater or different detail on those that were.

One aspect of the project that might have been developed further was the way in which the participatory arts projects contributed to the final research outputs. Although photographic and video material was shared with the team during the project, sat alongside and illustrated the project papers and reports on the CRESR and JRF websites and promoted the findings via exhibition and book, the work did not directly feed into the formal research to any great extent. Both myself and the social researchers involved identified potential ways in which this might happen (for instance having hypertext links embedded in pdf reports that linked to relevant online films or imagery). However, the scope of the project and time constraints prevented these potential synergies from being pursued.

Reflecting on Participatory Practice

The remainder of this paper reflects on three key issues for participatory photographic practice and visual research that have arisen from the LTC project and the other work discussed above.

Facilitator and Participant: The Balance of Authorship

Photography consists of a number of discrete creative activities including: concept; capture; selection; processing (developing, cropping, adjustments, manipulations); context (caption, juxtaposition, sequence) and output (print, exhibition, on-line). Within participatory arts projects some of these creative activities are handed over to project participants, while the artist/photographer retains others. An important question is the extent to which the artist/photographer is willing to relinquish authorship of the work to the participant. In some cases artists may wish to retain creative control of content with participants merely providing raw material for them to work with, while in others the artist’s ideas might find expression through the framing and facilitating of the project with participants taking greater control of not just the image making but also the editing and presentation of the work.

Nevertheless, giving authorship to the participant is not simply a question of stepping back and leaving them unsupported but rather of finding the balance whereby they have sufficient support and encouragement to produce the work successfully, without the facilitator’s personal views or aesthetic coming to dominate. There are also a number of aspects of participatory working that require the facilitator to consciously adopt the role of editor or supervisor and retain control (or authorship) of certain aspects of the work, for if they do not the work will may not be completed or may fail to reach or engage its audience.

Participants involved in photo editing and captioning process almost always require support and encouragement in selecting images and writing captions. From my experience, those left to caption images on their own are likely to write only a word or two, or perhaps a short sentence at most. Often, participant photographers, especially young people and children, struggle to find anything to say. This may be in part a reluctance to write (perhaps due to a lack of confidence) but also reveals a lack of understanding concerning how the image might need to be contextualised to have meaning to someone else.

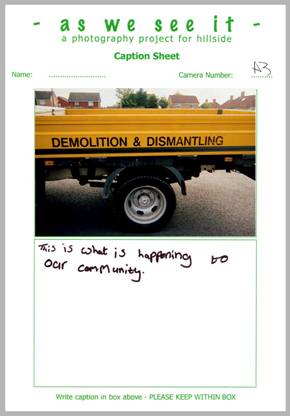

Figure 8: ‘This is what is happening…’ 2007

Caption sheet and image from ‘As We See It’ a photography project for Hillside, Huyton, Knowsley, part of the ‘Living Through Change’ project.

Often meaning is obvious to the maker and text seems an unnecessary addition, thus some amount of encouragement or guidance is needed to elicit a caption. For example, during one of the captioning sessions at the Hillywood centre in Huyton, Knowsley, the young girl who had taken the image in Figure 8 could not think of a caption. When asked why she had taken an image in which the view of her community was blocked by a truck on which was written ‘demolition and dismantling’ she replied ‘because this is what is happening to our community’. This was the text that she then added to the photograph.

Unintentionally, heavy-handed encouragement or guidance might lead to the participant’s voice being dominated by the artist or researcher and care is needed to ensure participant voices find expression. Facilitators can be tempted to slip from supporting into leading participants, especially if strong images are ignored or captioned with throwaway comments when an insightful caption might make a powerful statement. Helpers at such sessions who might be teachers, youth workers or others often encourage participants to rewrite captions to correct spelling, legibility and grammar which can change the meaning and lessen the immediacy of the caption. A certain level of editorial control is, however, required to avoid undue repetition and duplication of subject matter and content and also to maintain both the visual and thematic interest and coherence of the body of work as a whole.

Having some form of visible public presence for the finished work is an important motivating factor for many participants in participatory projects and is also key in providing the extended dissemination of project findings that is often expected of such work. Given that the final output would usually be a public display in the form of an exhibition or publication (physical or virtual), work has to be engaging not just in terms of its expressive or informative content (as it would in a research context) but also in terms of the aesthetic qualities and, to a lesser extent, technique.

Thus, for participatory arts projects it is essential for the facilitator to maintain some control of the technical and aesthetic quality of visual outputs to ensure the acceptance and success of such work in exhibition and publication. This is perhaps a key difference between the use of participant imagery and comment in participatory arts activity as compared to alternative research methods and adds a further dimension to the editing process.

Consent, Engagement and Dissemination

Two key benefits of participatory arts activity within a research context, namely increased subject engagement and wider dissemination and promotion of research, sit somewhat uncomfortably alongside one another. In order to use participant artwork in research and participatory projects and to reproduce this material each subject has to give their informed consent, in the form of a model release, and sign over or license copyright in any artwork produced. This is increasingly important and complex due to the range of outputs now being used in dissemination. The detail and formality of these agreements can prove off-putting and problematic, especially in the sensitive situations with ‘hard to reach’ subjects that such activities are often designed to address.

The very nature of the media concerned (photography, video and audio) is also problematic due to its indexical nature; participants are more clearly visible, their voices are heard, details of their lives are revealed, if not their physical appearance itself, making them far more identifiable than they would be in conventional research practices. Attempts can be made to preserve the anonymity of participants, but this can undermine the sense of authenticity that such methods are designed to bring (Figure 9 and 10). It is also the case that all the subjects of participants photographs should provide informed consent and it is highly unlikely that a participant would be willing or able to obtain consents of releases in such cases (see Figure 10).

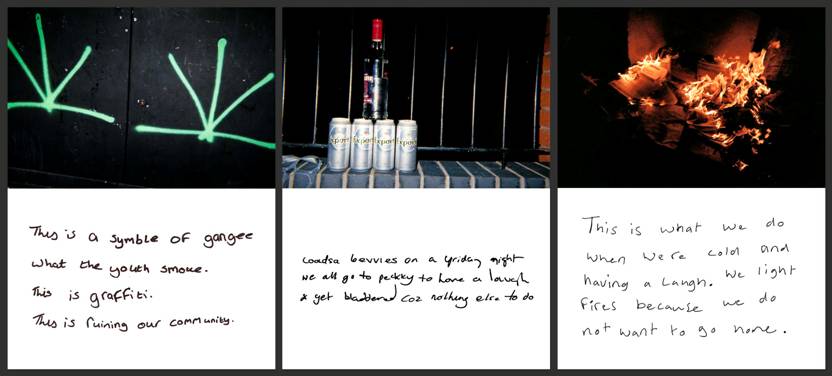

Figure 9: ‘Nothing else to do…’ 2007

Details used in place of images of young people (see Figure 10) in order to preserve anonymity in a visual narrative created for exhibition. Photographs and captions by members of the Hillywood Youth Club, Huyton, Knowsley, as part of the ‘Living Through Change’ project.

Figure 10: Participant Image from Hillside Estate, Huyton, Knowsley

Image taken by Hillside participant selected and caption for inclusion alongside those in Figure 9. Although the participant had provided consent some of his subjects hadn’t and thus the image wasn’t used.

Until recently such concerns were less problematic within documentary practice, where it has been common for UK photographers and filmmakers to have the freedom to use imagery within fine art, documentary, editorial or other non-commercial contexts without obtaining model releases. Increasing litigation is, however, causing both practitioners and clients to frequently request permissions in these situations in order to cover every eventuality, thus perhaps limiting potential subjects and access.

Whilst the issues of consent and copyright are often explored in relation to project ethics and participant rights (see for instance Gross et al., 1998; Prosser and Loxley, 2008; Hubbard, 2007), it is my experience that the different and, at times, conflicting roles that such material is now expected to fulfil are exerting an increasing influence on the design and delivery of projects and the editing of resulting work. The content and appearance of outputs is also being affected as it becomes increasingly difficult to include images of people.

Giving Voice, Taking Pictures

Participatory projects allow photographers, filmmakers or researchers to document, by proxy, situations, locations or people that would otherwise be beyond their reach or in some way compromised by their presence. Without doubt, such projects have the potential to engage and empower the subjects of social research or documentary practice, capture views that might otherwise be overlooked or ignored and as such they can ‘give voice’ to participants. Such material also has the potential for presentation and distribution in a range of contexts beyond those usually open to social research or documentary, in part due to its content and in part thanks to the range of media and outputs utilised.

Whilst not denying the value and power of imagery produced through such means, one should perhaps question the authorship of the final work (the balance between ‘facilitator’ and ‘participant’) and examine exactly whose thoughts and opinions are being conveyed and whose voice is actually being heard. Such work often suggests that we are being shown a relatively unmediated, authentic ‘insider’ view rather than that of an outside observer (photographer or researcher) and the crucial roles of devising, briefing, editing and presentation (often undertaken by the facilitator) can be minimised, overlooked or even ignored in favour of a focus on the contribution of the participants.

It should be noted that there is nothing intrinsic to these approaches that in any way guarantees their authenticity or accuracy anymore than there exists with conventional research or documentary photography, even though they may appear more authentic. We are, as ever, reliant on the honesty, authenticity and ethics of the researcher, photographer or facilitator concerned. Brian Winston suggests that ‘We must be sophisticated enough not to believe a photographic image is like a window on the world, a window unmarked by the photographer’s fingerprints; but to acknowledge the presence of the photographer is not necessarily to deny totally that one can still see something of the world. You can.’ (Winston, 2000: p166-167). In the case of participant imagery not only do we have to acknowledge the presence of the participant photographer, but also that of the artist or researcher facilitator who is less visible still, but whose influence is undoubtedly felt.

Participant generated imagery or collected vernacular material can seem to have a direct link to its subject in a way that artist or researcher generated material does not. Both the snapshot, ‘low-fi’ aesthetic of such imagery and the hand written or spoken text that are common in visual research and participatory photography have the feel and character of the artefact. The fact that these objects were created and handled by someone other than the researcher, documenter or artist who is directly experiencing the situation being researched or documented suggests that such work is some how a part of the subject, a fragment or shard of that experience. This quality of the artefact brings a sense of authenticity to participant imagery, artwork and writing.

As part of his practice, Canadian artist Luis Jacob employs appropriation and the reuse of found imagery to produce albums and installations of photographs that suggest new narratives through their juxtaposition and sequencing. This work exploits the ‘artefactness’ of the source imagery that Jacob explains as follows:

“Working with original images gives an artefact quality to the photographs, one that emphasizes not only their image content, but also their original context. Their artefact quality brings not only the imagery into dynamic play within the Album, but also brings into play the various life-worlds that the images originally inhabited”. (Heather, 2008)

Whilst the artefactness of participatory outputs may provide a link to the subject and directly deliver resident or participant voice and views, it can also, quietly, act to mask the role of the facilitator or researcher. Such work is often engaging and appealing and far more likely to be seen as authentic and ‘honest’ by the viewer who is encouraged by both content and aesthetic to take it at face value. This aspect perhaps tempts us to lower our guard in terms of our otherwise increased scepticism regarding photographic truth and authenticity. However such work might just as easily mislead as inform the viewer and disenfranchise as empower the subject.

In viewing such material it is thus essential to ask questions about its production and authorship, to enquire about the relative roles of participant and facilitator and to gain understanding of the editing, selection and presentation of material. In short, we should weigh how much has been given to the participant against how much has been taken from them.

Conclusions

In this paper I have attempted to bring together my thoughts and reflections on two different areas of practice; visual research and participatory documentary photography. I have briefly explored some of the similarities and distinctions between these practices based on my own experiences. Increasingly, social researchers are adopting and applying photographic skills whilst photographers and artists appropriate the techniques of survey and research in their documentary photography and artwork. Indeed, as I have shown, they can sometimes be found working side by side on the same projects. I feel that study of such crossover practice from these different points of view (documentary photography, participatory arts and social science) is beneficial to these fields and underrepresented.

My reflection on these practices and my own experience of working with participatory photography has identified some key issues deserving further study. These issues might be summarised as: the differences between visually similar material produced by social research and participatory arts or documentary photography and a consideration of cross practice contributions; clarity regarding the balance of authorship between facilitator and participant in the planning, delivery and use of participatory materials; the implications and impact of consent and copyright agreements on individual participants and project work; and the masking effect of the artefact based nature of much participatory work in terms of the influence of the editorial control of the facilitator.

1 Further details and more images from this and the author’s other projects referenced in this paper, may be found at: http://anthology.co.uk/photos_part_menu.html

2 Material from the ‘Living Through Change’ project may be found at: http://research.shu.ac.uk/cresr/living-through-change/index.html

Some of the discussion contained in this paper is developed from the authors contribution to an unpublished paper entitled ‘Exploring the Use of Photography in Social Policy Research: A Case Study’ co-written with two colleagues on the ‘Living Through Change’ project; Elaine Batty and Paul Hickman who I would like to thank for their advice and support.

Andrew Robinson, Department of Media Arts and Communication, Sheffield Hallam University, Howard Street, Sheffield S1 1WB. Email: andrew.robinson@shu.ac.uk

Barthes, R. (1981) Camera Lucida. New York: Hill and Wang.

Becker, H.S. (1974) Photography and Sociology, Studies in the anthropology of visual communication, 1,1

Becker, H.S. (1994) Visual Sociology, Documentary Photography, and Photojournalism: It’s (Almost) All a Matter of Context. Visual Sociology, 10, 1-2.

Berger, J. and Mohr, J. (1982) Another Way of Telling. Cambridge: Granta.

Billingham, R. (1996) Ray’s A Laugh. Zurich: Scalo.

Clark, L. (1971) Tulsa. New York City, NY: Lustrum Press.

Clark, L. (1983) Teenage Lust. New York City, NY: Self Published.

CRESR (2011) Living Through Challenges in Low Income Neighbourhoods: Change, Continuity, Contrast. Final Research Report. Sheffield: Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield Hallam University.

Davidson, B. (1970) East 100th Street. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Dolberg, E. (2010) Open Shutters Iraq. London: Trolley Ltd.

Elkins, J. (Ed), Photography Theory (Art Seminar). Routledge; 13 Dec 2006

Germain, J., Azevedo, P. and Godoy, M. (1998) No Mundo Maravilhoso Do Futebol. Amsterdam: Besalt Publishers.

Germain, J., Azevedo, P. and Godoy, M. (2007) Photoworks Magazine, Issue 9, October 2007.

Goldberg, J. (1985) Rich and Poor. New York: Random House.

Goldberg, J. (1995) Raised by Wolves. Zurich, Scalo.

Goldin, N. (1986) The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. New York: Aperture.

Gross, L. Katz, J.S. and Ruby, J. (1988) Image Ethics: The Moral Rights of Subjects in Photographs, Film and Television New York, Oxford University Press.

Harper, D (1998) An Argument for Visual Sociology, in ‘Image Based Research’ Jon Prosser (ed.). Oxon: RoutledgeFalmer.

Heather, R. (2008) Artists at Work: Luis Jacob. Afterall Journal,Published 12.03.2008.

Holdt, J. (1885) American Pictures: A Personal Journey Through the American Underclass. American Pictures Foundation.

Hubbard, J. (1991) Shooting Back: A Photographic View of Life by Homeless Children. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Hubbarb, J. (2007) Shooting Back: Photographic Empowerment and Participatory Photography. PDF available at: http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~cultagen

/programs/files/Hubbard%20-%20Shooting%20Back.pdf

Prosser, J. and Loxley, A. (2008) Introducing Visual Methods ESRC National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper.

Robinson, A. (2009a) Fire, Earth and Water, DVD. Sheffield: CRESR, Sheffield Hallam University. [sections available to view at: http://www.jrf.org.uk/film-gallery/poverty-and-place and http://research.shu.ac.uk/cresr/living-through-change/amlwch.html]

Robinson, A. (2009b) Unpublished interview with ‘Living Through Change’ project. Director Professor Ian Cole.

Robinson, A. (2011) What is Happening to Our Community, Self Published, UK. [Available to view at: http://www.blurb.com/bookstore/detail/2319892]

Rosler, M. (1989) In around and afterthoughts (on Documentary Photography), In: R. Bolton (ed.) The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

Skerrett, P. (2005) In Conversation; Julian Germain and Penny Skerrett, Archive, October 2005. Bradford: National Museum of Photography, Film and Television.

Sontag, S. (1979) On Photography. London: Penguin.

Sultan, L. (1992) Pictures From Home. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Syson-Nibbs, L., Robinson, A. et al (2009) Young Farmers’ Photographic Mental Health Promotion Programme: A Case Study. Arts & Health, 1, 2 (Sept 2009).

Price, D. (2004)Surveyors and Surveyed: Photography Out and About, In: Wells, L (ed.) (2004) Photography: A Critical Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge.

Wang, C. and Burris, M. A. (1994) Empowerment through Photo Novella: Portraits of Participation. Health Education Quarterly, 21, 2, 171-186.

Wang, C., Burris, M.A. and Xiang, Y.P. (1996) Chinese Women As Visual Anthropologists: A Participatory Approach to reaching Policy Makers. Social Science and Medicine, 42, 10, 1391-1400.

Wang, C. and Redwood-Jones, Y. (2001) Photovoice Ethics: Perspectives From Flint Photovoice. Health Education and Behavior, 28, 5, 560-572.

Winston, B. (2000) Lies, Damn Lies and Documentaries. London: British Film Institute p. 166-167.