Abstract

The European Commission has stated that it does not support a European definition of fuel poverty, and that a common definition would be inappropriate due to the diverse energy contexts found across the European Union. Using official EU policy documents from 2001 to 2014, this paper will demonstrate that contrary to the European Commission’s stance, many of the EU institutions and consultative committees are in favour of a common European definition of fuel poverty, and have been arguing for the establishment of a definition for at least seven years. This paper will argue that a definition is vital for raising the profile of fuel poverty and ensuring it is recognised as a policy issue by all Member States of the EU, particularly at a time of rising energy prices, stagnating wages and growing concerns about energy security and climate change.

Introduction

Fuel poverty occurs when households have insufficient funds to pay for the most basic levels of energy needed to provide them with heating, lighting, cooking, and appliance use (Boardman, 2010). This is often the result of a combination of poor and inefficient equipment and building fabric, high energy costs, and low household income. Additional contributory factors include above average energy needs, perhaps as a consequence of disability (Snell et al., 2015), as well as an absence of savings and living in rented accommodation, both of which limit an occupant’s opportunities to improve their dwelling (Boardman, 2010). Fuel poor households generally have two options:

- Invest an above average amount of their income on heat, cooling, light, cooking, and appliance use, with concomitant effects on how much they are able to invest in other basic needs such as food and transport.

- Go without these essential commodities, resulting in a cold and uncomfortable home, and reduced living standards.

In most cases, studies indicate that households in fuel poverty usually do both, which can result in significant deteriorations to people’s physical health and mental wellbeing (Liddell and Morris, 2010; Marmot Review Team, 2011; Liddell and Guiney, 2014, Snell et al., 2015; Thomson and Thomas, 2015). At worst, fuel poverty can cause premature death, with links to excess winter mortality (Liddell et al., 2016; Healy, 2003). Living in fuel poverty also impacts on everyday practices, lifestyles and social exclusion (Anderson et al., 2010; Brunner et al., 2012; Middlemiss and Gillard, 2015).

Several European countries, such as France, the UK, Ireland, and Slovakia, have begun to signal a greater interest in the societal implications of fuel poverty, as reflected by a growing number of national policy frameworks to define, measure and alleviate the phenomenon. By contrast, policy specifically addressing fuel poverty at the EU-level has been limited and piecemeal, with no dedicated policy package in place to address fuel poverty (Thomson and Snell, 2013). This situation persists in spite of considerable support from EU institutions such as the European Parliament, and the European Economic Social Committee (EESC), for a comprehensive pan-European approach to addressing fuel poverty. As will be elaborated in the following section, policy measures that have the potential to alleviate some aspects of fuel poverty are currently fragmented across a range of EU Directives. The main legislative requirements to address fuel poverty can be found within the 2009 European Council Directives concerning the internal natural gas and electricity markets, which both acknowledge that energy poverty exists and require ‘affected’ States to develop action plans. However, no definition of the problem is provided, nor is criteria for an ‘affected Member State’ given.

The EU is the focal point of this paper as it is the most important agent of change in contemporary government and policymaking in Europe (Wallace et al., 2010: 4); decisions made at the EU scale have considerable impact on policymaking activities in individual countries, for both Member States and their non-EU neighbours alike. Given that many of the drivers and exacerbators of fuel poverty transcend national boundaries, or are strongly influenced by global pressures, affecting change at the EU-level may enable the development of comprehensive alleviation policies, focussed on transnational structural issues. For instance, energy affordability at the national level is influenced, to varying degrees, by volatile global oil prices, EU-mandated climate change levies and obligations, and European-wide energy market liberalisation (Snell and Thomson, 2013). Yet, as Bouzarovski and Petrova (2015a) note, fuel poverty is rarely seen as a European issue.

To date only limited attention has been paid to EU policy discussions on fuel and energy poverty, with just three academic studies by Thomson (2011), Bouzarovski et al. (2012), and Bouzarovski and Petrova (2015a). All three studies have mainly centred on documents and events from 2009 onward, and none of the authors engage with the earliest discussions on fuel poverty and energy poverty at the EU scale. Yet tracing the early emergence of fuel poverty related concerns in EU policymaking is a necessary process for understanding the policy legacies which emerged from earliest deliberations, since these have affected the evolution of many policies and institutional structures which support actions on fuel poverty. This paper begins to address this gap in policy knowledge by examining policy statements over the longue durée, with a central aim of testing whether the European Commission’s stance on defining fuel poverty reflects broader concerns expressed by other policy actors. In doing so, the paper reveals that fuel poverty concerns have been a feature of European discussions since 2001.

The paper is arranged across four sections. The next section provides a short background on terminology, the policy contexts at the Member State and European levels, and the key arguments in favour and against establishing a common definition. The subsequent section outlines the methods and data used. Following on from this, the analysis of EU policy documents is arranged according to three key phases in policy. The concluding section discusses the importance of a pan-EU definition of fuel poverty, and calls for expanded policy protection for fuel poor households.

Background

Use of terms

At the European scale there is an inconsistent use of terminology, with the terms ‘energy poverty’ and ‘fuel poverty’ often being used interchangeably. In reality they can be treated as distinct terms, with energy poverty referring to the lack of access to modern energy services in developing countries (as used by Bazilian et al., 2010; Birol, 2007; and Sagar, 2005), and fuel poverty referring to a problem of affordability in some of the world’s most developed countries (Househam and Musatescu, 2012). Alternatively, they can be treated as related concepts, with the distinction being the fuel types covered by each term. For example, the European Commission (2010a) state that energy poverty refers only to gas and electricity, whilst fuel poverty covers all fuel sources used in the home. Lastly, the terms can be understood to mean the same thing (Boardman, 2010), and indeed, the terms have been used interchangeably in a number of key EU policy documents (for example, European Parliament, 2010; European Commission, 2010a; 2010b; EESC, 2011). More recently, Bouzarovski and Petrova (2015b) have made a persuasive argument in favour of this latter standpoint, stating that all forms of fuel and energy poverty, in both developed and developing countries, are underpinned by a common condition: “the inability to attain a socially and materially necessitated level of domestic energy services” (Bouzarovski and Petrova, 2015b: 31).

This paper adopts the last standpoint, but opts to refer mainly to fuel poverty given the widespread acceptance of the term throughout the industrialised world (Liddell et al., 2012). The exceptions are when quoting directly from sources that use the term energy poverty.

Fuel poverty as a policy problem

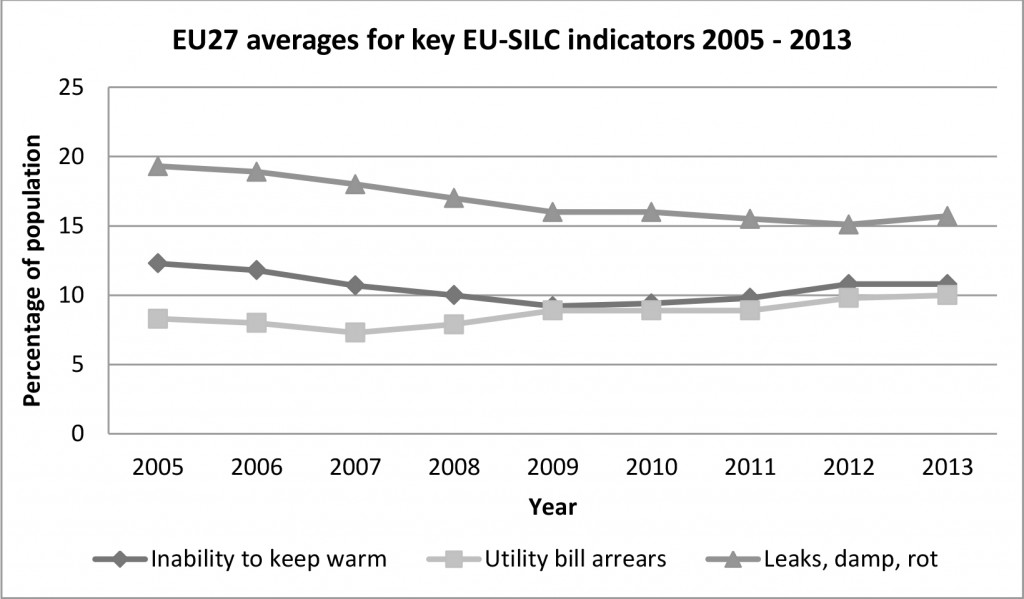

Figure 1 displays the EU27 averages for three widely used indicators from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), for 2005 through to 2013. The data indicates that a sizeable, and rising, proportion of the EU population are struggling to attain adequate warmth, pay their utility bills on time, and live in homes free of damp and mould.

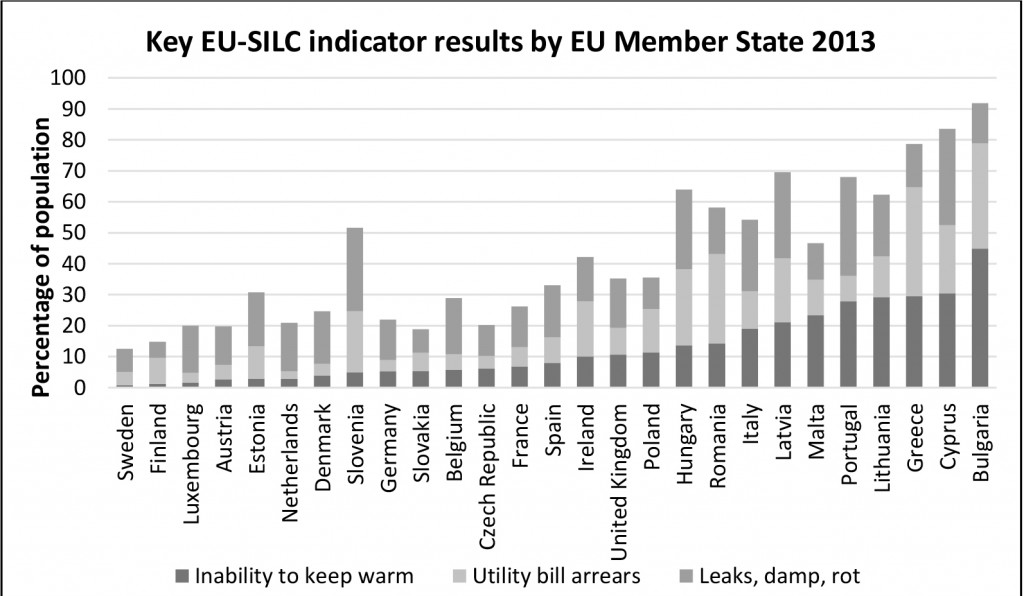

Broadly speaking, previous studies have shown fuel poverty is prevalent across the whole of the EU (Healy and Clinch, 2002; EPEE, 2009; Thomson and Snell, 2013), with a particularly strong concentration in Central and Eastern Europe (see Buzar, 2007; Tirado Herrero and Ürge-Vorsatz, 2012), as the disaggregated EU-SILC results for 2013 in Figure 2 shows.

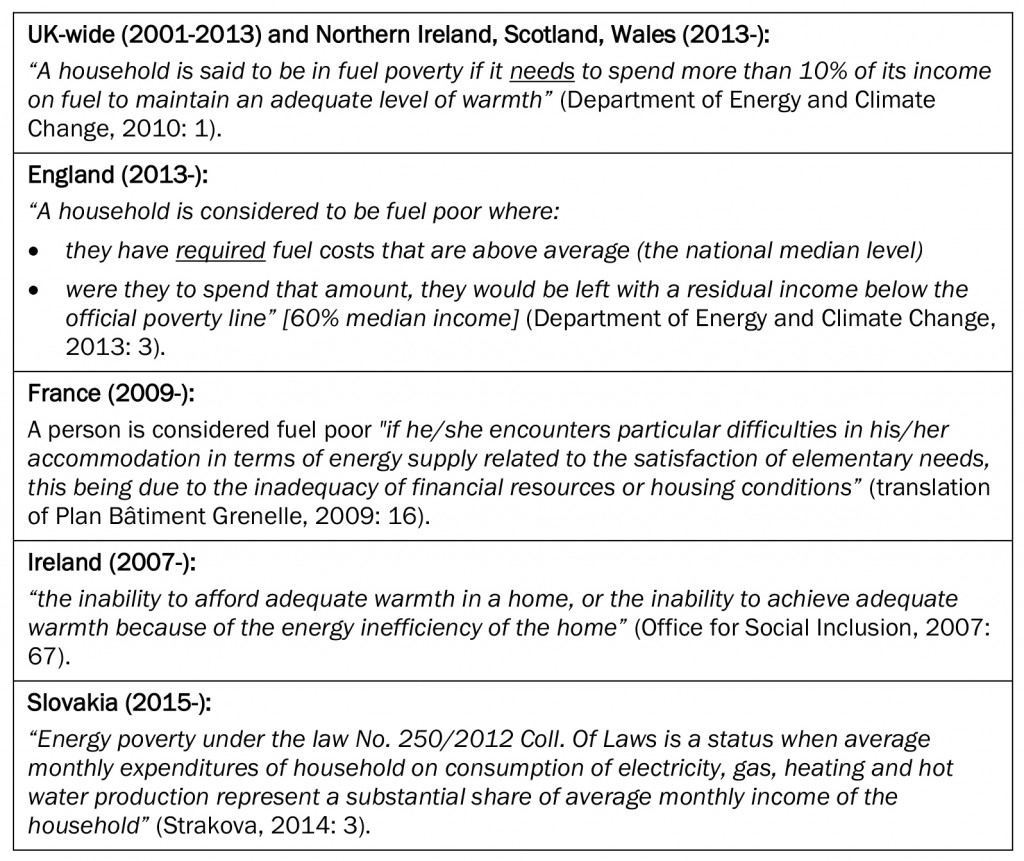

Several countries have begun to signal greater interest in fuel poverty, as reflected by a growing number of national policy frameworks to define, measure and alleviate the issue. At the Member State level four of the twenty-eight EU countries now have an official definition of fuel poverty: the United Kingdom, France, the Republic of Ireland, and more recently Slovakia, as outlined in Table 1. It should be noted that within the UK, fuel poverty is a devolved policy matter, and since the official review of fuel poverty by Professor Hills in 2012, the definition of fuel poverty used by the devolved administrations of the UK has diverged, with Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales opting to retain the 10 per cent measure.

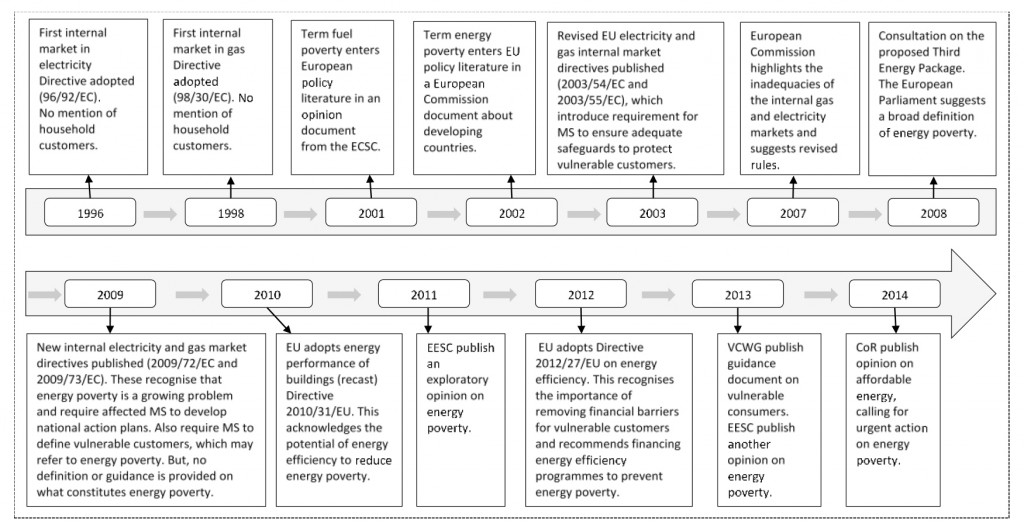

In addition to this, in advance of its 2010 Presidency of the Council of the EU, Belgium requested the EESC to prepare an opinion document on energy poverty in the context of liberalisation and the economic crisis (EESC, 2011). However, elsewhere the issue of fuel poverty has not yet entered official policy agendas. In part, this may be due to the multidimensionality of the phenomenon, meaning that it requires joint multi-agency policy solutions. Findings from decision-maker interviews reported in Bouzarovski et al. (2012: 78) suggest that this situation may also be the result of the limited scientific evidence base, the unwillingness of some Member States to recognise fuel poverty, and the lack of a strong institutional centre within political initiatives to address the problem. The limited policy interest demonstrated at the Member State level is also apparent at the EU-level, since there is no accepted definition of fuel poverty or energy poverty, nor is there a specific legislative programme to address fuel poverty. However, there have been several European Council Directives that contain measures that have the potential to alleviate some aspects of fuel poverty, as the timeline in Figure 3 outlines. The timeline begins in 1996, with the publication of the first EU electricity Directive (96/92/EC), which sets out rules for the creation of an internal market and market opening. Explicit recognition of household customers in energy markets, and in particular vulnerable customers, was first noted in 2003 in revised gas and electricity internal market Directives. Six years later ‘energy poverty’ was given legal recognition in the successive 2009 internal market Directives, and thereafter the link between energy poverty and energy efficiency was made in the 2012 Directive on energy efficiency.

Arguments in favour of a pan-European definition of fuel poverty

Given the body of empirical evidence that shows fuel poverty is both prevalent across Europe, and has wide-ranging societal impacts, coupled with the slow moving policy developments described above, it is argued by some that a pan-European definition is a necessary catalyst for the alleviation of fuel poverty (EPEE, 2009). Indeed, many of the driving factors of fuel poverty transcend national boundaries. For instance, energy prices at the national level are influenced by global oil prices, EU-mandated climate change levies and obligations, and European-wide liberalisation of gas and electricity markets. Increases in extreme weather patterns, which affect heating and cooling demand, can be partially attributed to global greenhouse gas emissions and associated climate change. Similarly, national wealth, employment opportunities and poverty levels are all shaped to some extent by globalisation and the increasing integration of many European economies, principally via the Eurozone. Overall, we identify three main arguments in favour of developing a common EU definition of fuel poverty, namely: recognition; clarification; and policy synergy.

In terms of recognition, Bouzarovski et al. (2012) argue that a common EU-level definition of energy poverty may give the problem better visibility at the Member State level. Whilst the European evidence base is fragmented, all studies published to date indicate that a significant proportion of households across Europe are struggling to achieve adequate energy services (e.g. Buzar, 2007; Thomson and Snell, 2013). Furthermore, consensus exists that fuel poverty is distinct from income poverty (Boardman, 2010; Hills, 2012), being caused primarily by poor energy efficiency and availability of affordable energy carriers. Within this context, increasing recognition of fuel poverty as a policy issue is vital, especially as the majority of Member States have yet to define the phenomenon of fuel poverty, and consequently, have not set any intermediate targets to alleviate it. Strengthening political visibility of fuel poverty at the European-scale may also afford policy actors opportunities to bypass political resistance at the national level. This is particularly pertinent in countries such as Germany, which, in the context of recent energy price rises resulting from its ongoing low-carbon energy transition, has been unwilling to recognise the existence of fuel poverty due to the significant political difficulties it would cause (Bouzarovski and Petrova, 2015a).

As for clarification, a major regulatory impediment to addressing fuel poverty is the unclear and often conflicting definitions of fuel poverty and energy poverty used by different EU institutions and researchers. The lack of clarity and understanding of defining fuel poverty has also led to many researchers inaccurately measuring fuel poverty in some European countries by misapplying the UK’s previous 10 per cent definition (Liddell et al., 2012). The most common inaccuracies result from a failure to understand the historical basis of the 10 per cent definition, which arose from a twice-median expenditure threshold (Boardman, 2010), and from using actual energy expenditure data without recognising the likelihood of underestimating prevalence (see Moore, 2012). Adopting even a general description of fuel or energy poverty at the EU-level would help to resolve the considerable terminological confusion that presently exists, and may pave the way for more detailed national definitions.

In terms of policy synergy, there is potential for achieving synergies both between fuel poverty policy and other policy domains, and with regard to policy cooperation between Member States. As the EESC remark, “Not all Member States are addressing this problem and those that are, act on their own, without seeking synergies with others, which makes it harder to identify, assess and deal with energy poverty at the European level” (EESC, 2011: 4). Furthermore, the EU already has a prominent policymaking role in related areas such as reducing income poverty and social exclusion, and promoting energy security and climate change mitigation, particularly as part of efforts to meet the Europe 2020 goals (European Commission, 2010c). Improving the prominence of fuel poverty as a policy problem might encourage greater collaborative working across departments, particularly if potential policy synergies and conflicts are recognised. For example, targeted energy efficiency investments have the potential to reduce fuel poverty whilst also contributing to climate change goals (Ürge-Vorsatz and Tirado Herrero, 2012; Snell and Thomson, 2013).

Arguments against a pan-European definition of fuel poverty

By contrast, there are a number of reasons why a pan-European definition of fuel poverty may not be desirable. These arguments principally relate to: limited evidence; comparability and relevance; and path dependency.

With regard to limited evidence, knowledge about fuel poverty in many parts of Europe is at a nascent stage. This is compounded by poor data availability, especially energy consumption and expenditure data (Thomson and Snell, 2014), resulting in many countries lacking a detailed understanding of energy expenditure patterns in fuel poor households. In combination this means that it is inadvisable to set fixed quantitative thresholds at the pan-EU scale. For example, whilst twice-median expenditure is one established threshold for indicating fuel poverty within the UK (Moore, 2012), elsewhere disproportionate expenditure may represent three or four times median expenditure.

In terms of comparability and relevance, a shared pan-EU definition would need to be relatively broad in order to accommodate the diversity of contexts found at the Member State-level, in terms of climate conditions, socioeconomic factors, energy markets and more. However, there is a risk that in so doing the definition becomes so broad that it loses relevance. It is clear in this regard that a shared EU definition would not be the finishing point; rather it would need to be expanded on at the Member State-level, with detailed national definitions that are specific to local contexts.

Path dependency is an additional concern. The concept of path dependency is derived from the historical institutionalist literature (Hall and Taylor, 1996), which argues that “small decisions about institutions and policy tools taken at one time can have a major influence over what is possible and realistic in the future” (Greer, 2008: 220). Path dependency is used to explain why inefficient or sub-optimal outcomes persist (Greer, 2008), with a central argument by Pierson that once a particular path is established, self-reinforcing or positive feedback processes make reversals very difficult (Pierson, 2004: 10). The ‘stickiness’ of fuel poverty definitions is evident from the UK example, where the 10 per cent definition was the official UK-wide definition from 2001-2013, and remains official policy in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. This underscores the importance of developing a pan-EU definition that will retain enduring relevance, but also the importance of developing national definitions that are supported by scientific evidence.

Methods and data

In the context of empirical evidence that indicates fuel poverty is a widespread policy problem, and the existence of EU Directives that suggest a degree of concern about the causes and consequences of fuel poverty, this paper presents a much needed analysis of EU policy documents over the longue durée. The analysis explores the evolution of policy discussions on fuel poverty at the EU-scale, and explicitly considers the following questions in order to examine both the level of concern, and desire for policy change at the EU-level:

- What are the origins of fuel and energy poverty discussions?

- Does the European Commission’s stance on defining fuel poverty reflect broader concerns expressed by other policy actors?

- What suggestions have been made to define fuel and energy poverty?

To address these research questions this paper uses EU policy documents from 2001 to 2014. The collection and selection of data was a two stage process, and formed part of a larger PhD research strategy. In the first stage documents published by EU institutions were obtained through a text search of documents archived on EUR-Lex (n.d.), a website maintained by the EU’s Publications Office that makes EU legal documents available to the public. The first search of EUR-Lex was conducted during March 2013 using the keywords ‘energy poverty’ and ‘fuel poverty’. Truncation was used to ensure that documents which used variants of these keywords, such as ‘energy poor’, were also included. A second EUR-Lex search was undertaken in October 2014, enabling several new policy statements to be included in the analysis. Overall the searches generated 185 unique document hits, originating from various EU institutions, including three advisory committees, and the European Commission, European Council, and European Parliament. The policy documents were coded using NVivo 10 software, and qualitative content analysis was used to analyse the data.

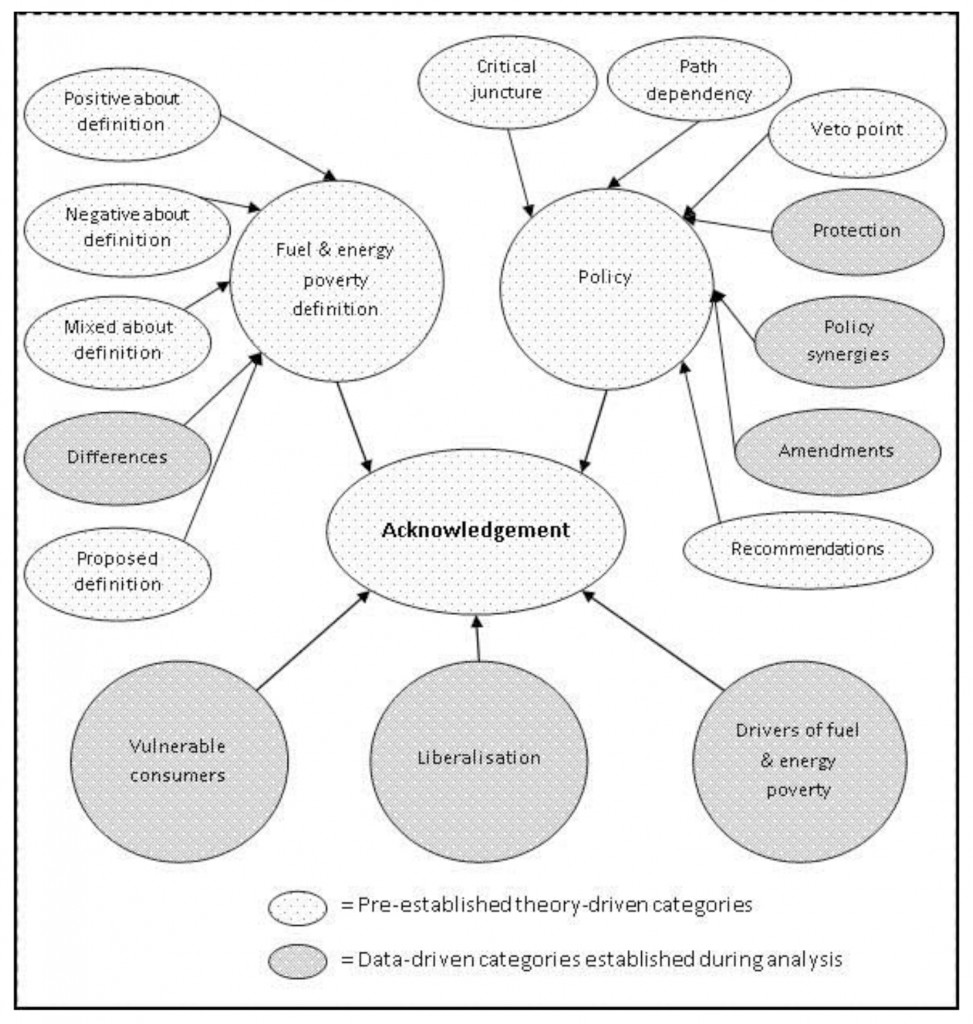

A hybrid process of inductive and deductive content analysis was used for coding categories, whereby theory-driven categories relating to specific research questions were established in advance of coding, and integrated with data-driven categories that emerged during coding. For instance, as displayed in the coding categories model in Figure 4, ‘liberalisation’ and ‘vulnerable consumers’ were two strong themes that emerged during coding, and so categories were created to accommodate these themes.

This method of analysis, which can be classified as a ‘directed content analysis’ (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005), was chosen for its flexibility and because it explicitly acknowledges that a priori knowledge of EU policy concerning fuel poverty and energy poverty exists, particularly as a result of the work undertaken by Thomson (2011), Bouzarovski et al. (2012), and Thomson and Snell (2013).

Tracing the development of EU fuel poverty policy

Overview

From the timeline shown earlier in Figure 3, three key phases in EU policy discussions and events can be identified, namely:

- Preliminary discussion concerning fuel and energy poverty from 2001 to 2006;

- A period of legal recognition for energy poverty from 2007;

- An enhanced focus on energy poverty and vulnerable customers from 2011 onward.

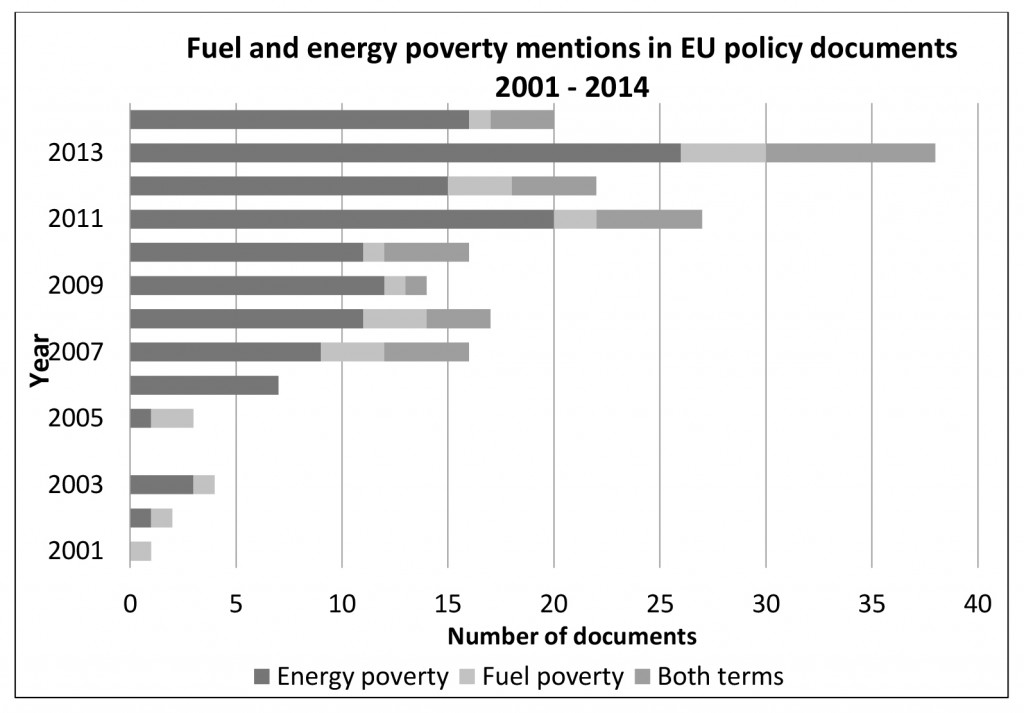

These key phases can also be discerned in Figure 5 below, which shows the number of fuel and energy poverty mentions in all EU policy documents from 2001 to 2014. As can be seen, fuel and energy poverty concerns are first expressed in 2001 and 2002, followed by a substantial increase in mentions only some time later in 2007, and a secondary increase from 2011 onward. Figure 5 also suggests that there may have been a high degree of inconsistency over time with regard to terminology, with a noteworthy proportion of policy documents using both terms. However, it should be noted that when a document uses both terms, it is not necessarily using them interchangeably, rather, they may be treated as separate concepts (as in European Commission, 2010a) – this distinction is not reflected in the figures below.

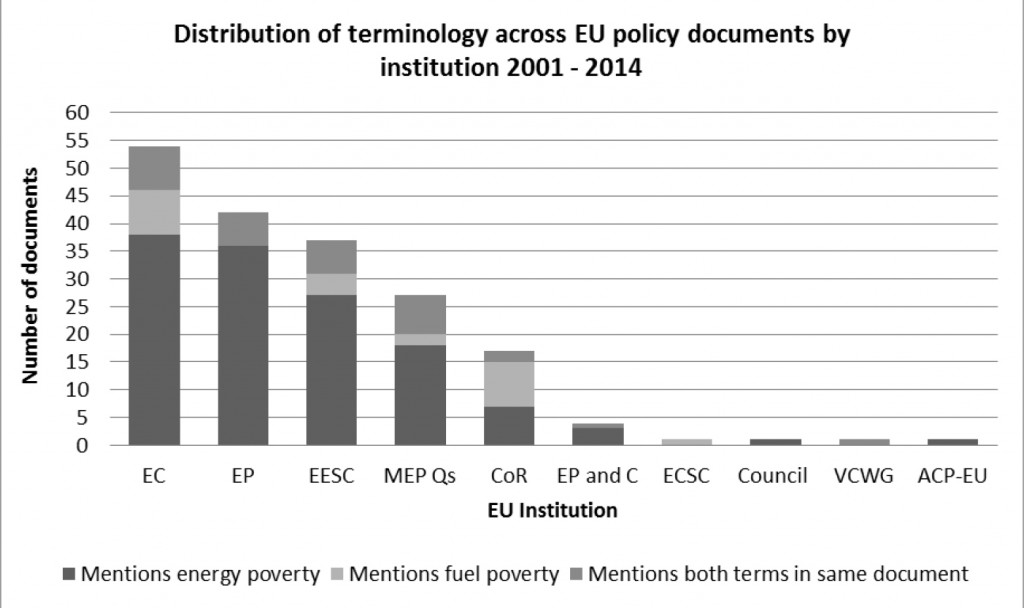

The inconsistency in the use of terms is also evident in Figure 6, which shows the overall distribution of terminology across the various consultative and legislative institutions of the EU. Many of the institutions, including the European Commission, have exclusively used the term fuel poverty at least once across this time frame. Overall, the main contributors to policy discussions are the European Commission, European Parliament and the EESC.

Figure 6: Distribution of terminology across all policy documents

Note: The following abbreviations apply: CoR = Committee of the Regions; ECSC = European Coal and Steel Community Consultative Committee; EC = European Commission; Council = European Council; EESC = European Economic and Social Committee; EP = European Parliament; EP and C = joint documents from the European Parliament and Council; MEP Qs = written questions from MEPs to the European Commission.

Preliminary EU level discussions on fuel and energy poverty 2001 – 2006

Examining the term fuel poverty first, this was introduced to the European policy literature in 2001 by the Consultative Committee of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). In an opinion document on climate change and emissions trading this noted:

“In adopting appropriate measures to encourage improved energy efficiency by the domestic sector, the EU and its Member States should avoid any measures that risk exacerbating fuel poverty” (ECSC, 2001: 2).

Beyond this sentence the ECSC did not elaborate on what they meant by ‘fuel poverty’. Subsequently, a further four documents were published between 2001 and 2006 that briefly discussed fuel poverty. The issue of fuel poverty was also debated in a written question to the European Commission in 2003 from Claude Moraes, a British MEP, who asked whether the Commission had undertaken any research on the issue. The response from the Commission in July 2003 is the earliest instance of the Commission officially engaging with the concept of fuel poverty. The answer clearly states that fuel poverty falls within the remit of energy policy, by way of public service requirements at the Member State level:

“For the Commission the question of fuel poverty enters into the bigger debate of public service aspects under energy policy. The Commission in its proposals amending the Electricity and Gas Directives has substantially strenghtened [sic] the public service aspects of the existing Directives to ensure that vulnerable customers will be sufficiently protected…” (Answer from Mrs de Palacio on behalf of the Commission, 2 July 2003).

The full response from the Commission also strongly implies a de facto usage of the term ‘vulnerable customer’ in place of fuel poverty, although the overlap between the concepts is not discussed, nor is guidance offered on what constitutes a vulnerable customer. The 2003/54/EC and 2003/55/EC Directives referred to in the Commission’s response formally introduced the term vulnerable customer into EU energy law, however, they made no mention of fuel poverty or energy poverty, but rather stated:

“Member States should take the necessary measures to protect vulnerable customers in the context of the internal electricity market. Such measures…may include specific measures relating to the payment of electricity bills, or more general measures taken in the social security system” (Directive 2003/54/EC: 39).

Nevertheless, the 2003 Directives are an important milestone as they incorporated minimum standards of protection for domestic customers into legally binding energy policies.

The origins of discussions on energy poverty in EU policy documents are somewhat different, being first used by the European Commission in a 2002 communication concerning energy cooperation with developing countries, which noted:

“Apart from the absolute priority of guaranteeing access to adequate energy services for the “energy poor”, demand-side cooperation is undoubtedly the most promising avenue of approach…that has to a large extent not been exploited so far in the developing countries” (European Commission, 2002).

However, this was in relation to a lack of access to modern energy services in developing countries. In all, energy poverty is mentioned across 12 documents between 2001 and 2006, but only two of these documents refer to European countries, both of which originate from the European Parliament.

Legal recognition of energy poverty 2007-2010

From 2007 onward, fuel and energy poverty concerns were more frequently discussed in EU policy documents, particularly during the preparatory stages of Directives 2009/72/EC and 2009/73/EC. This second phase is characterised by legal recognition of energy poverty in the 2009 internal gas and electricity market Directives, and a focus on the energy performance of buildings (in a 2010 Directive).

Moves to update the 2003 internal gas and electricity market Directives were initiated by the European Commission (2007a), who highlighted the inadequacies of the internal markets, particularly in terms of the lack of meaningful competition in many Member States. Within the communication, both vulnerable consumers and the issue of fuel poverty were noted, and the Commission emphasised the lack of action at the Member State level in defining and protecting vulnerable customers, in spite of binding legislative requirements to do so.

Despite recognising energy poverty in two further communications (2007b; 2007c), and noting the lack of action at Member State level, the Commission initially opted for a ‘soft law’ approach to protecting vulnerable consumers by way of a consumer charter. In a communication that introduced the concept of a European Charter on the Rights of Energy Consumers (2007d), the Commission stated that market mechanisms alone cannot fully ensure consumers’ best interest (2007d: 2). The Commission also reaffirmed the need for the EU to go further in tackling energy poverty, and repeated its earlier criticism of Member States for failing to support vulnerable consumers (2007d: 5). However, the Commission then stated that the charter would not be legally binding, and hence the status quo was preserved.

The decision to use non-binding legislation was bluntly criticised by the EESC, among others, who noted:

“A Charter is being published because the rights that currently exist are not properly respected…transposition into national law has been deficient. The Commission has the power and the responsibility to intervene, but prefers a non-binding instrument, even though it knows full well that the market alone is not in a position to provide appropriate and adequate solutions” (EESC, 2008a: 31).

The EESC also argued for a common definition of a vulnerable customer, later stating that harmonised standards across Europe would prevent discriminating against anyone and avoid distorting competition (EESC, 2008a), particularly as many energy suppliers operate across multiple countries.

Throughout 2008 the majority of publications issued concerned the proposed internal energy market Directives, with numerous opinions produced by the European Parliament, Committee of the Regions (CoR), EESC, and the Commission. The CoR (2008) stressed that discussions should centre on the consumer, and that the proposed European Charter on the Rights of Energy Consumers should have legal force. Similarly, as noted above, the EESC (2008a; 2008b) called for the Commission to highlight the importance of vulnerable consumer protection, and argued that a common definition of energy poverty should be established, although they do not expand on the recommendation.

The European Parliament, which has the power to suggest amendments to Directives, proposed various amendments to the draft internal market Directives (2008a, 2008b), including the addition of two new paragraphs, which introduce a broad description of energy poverty and energy affordability:

“40. “energy poverty” means the situation where the members of a household cannot afford to heat their home to an acceptable standard, based on the levels recommended by the World Health Organisation;

41. “affordable price” means a price defined by Member States at national level in consultation with national regulatory authorities, social partners and relevant stakeholders while taking account of the definition of energy poverty provided for in point 40” (European Parliament, 2008a: 150).

Moreover, the European Parliament amended a paragraph to mandate Member States to explicitly recognise energy poverty:

“3…Member States shall recognise energy poverty and shall provide definitions of vulnerable customers. Member States shall ensure that rights and obligations linked to vulnerable customers are applied …” (European Parliament, 2008a: 150).

An additional amendment added a new paragraph to the Directives that requires Member States to create national definitions of energy poverty and action plans:

“…Member States shall take appropriate measures to address energy poverty in national action plans in order to ensure that the number of people suffering energy poverty decreases in real terms…Each Member State shall be responsible for providing, in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, a definition of energy poverty at national level…” (European Parliament, 2008a: 151).

The European Parliament proposals outlined above would have made defining and addressing energy poverty an explicit necessity within each Member State. However, in the subsequent approval phase via the European Council, the amendments were rejected. In a response document, the European Commission stated, amongst other things, the reasons why it does not support an EU definition of energy poverty:

“Energy poverty is not a concept that has been used in all Member States and measures to address poverty require all aspects of energy and social policy to be taken into account. The Commission believes that using energy policy as the sole tool would distort the operation of the market for energy…” (European Commission, 2008: 6).

The final Directives (2009/72/EC and 2009/73/EC), which are the main pieces of EU legislation currently in place, include the following requirements:

“…Member States which are affected and which have not yet done so should therefore develop national action plans or other appropriate frameworks to tackle energy poverty, aiming at decreasing the number of people suffering such situation” (Directive 2009/72/EC: 7)

“…each Member State shall define the concept of vulnerable customers which may refer to energy poverty and, inter alia, to the prohibition of disconnection of electricity to such customers in critical times” (Directive 2009/72/EC: 11).

Whilst it is undoubtedly an achievement that energy poverty requirements have been included in binding legal documents, this final product does not reflect the opinions expressed by the European Parliament, CoR, or the EESC. The Directives fail to offer even a basic description of energy poverty, nor any guidance on determining whether a Member State is ‘affected’. The loose phrasing of the Directives allows Member States to absolve themselves of responsibility in addressing energy poverty. Similarly, no description or guidance is offered in relation to vulnerable customers, which is remiss given the Commission’s earlier criticism of the Member States.

In a working document produced a year later, the European Commission reaffirmed its opposition to common definitions of energy poverty and vulnerable customers, arguing that it would not be appropriate given the diverse situations of EU energy consumers (European Commission, 2010a: 12). The Commission then goes on to argue that there is no consensus on the concept of energy poverty, and that fuel poverty and energy poverty are separate issues, differentiated by the energy sources covered by each term. The European Commission’s statements exemplifies the confusion that exists in European policymaking. Furthermore, the Commission’s conceptualisation of fuel and energy poverty are at odds with previous statements made by other EU institutions. On a more positive note, their statements have served to highlight a critical issue in current European fuel poverty legislation, namely that only gas and electricity customers are protected by law, and even then only albeit piecemeal.

Enhanced focus on energy poverty and vulnerable consumers 2011 – 2014

The final phase in the development of EU policy is characterised by a growing focus on fuel and energy poverty concerns, and vulnerable consumers. During this latter period, consultative institutions played a larger role in drawing attention to the issues of fuel and energy poverty, as evidenced by the publication of two opinion documents from the EESC specifically on the topic of energy poverty.

The first of the two EESC opinion documents was published in 2011, and at the request of the Belgian government focused on energy poverty in the context of liberalisation. Whilst opinion documents are not binding, they nevertheless play an important role in persuasion and also in offering new interpretations. The EESC argued that energy poverty should be tackled at all tiers of government, and that the EU should adopt a common general definition of energy poverty, which could then be adapted by Member States (EESC, 2011: 1). The EESC highlight the problematic multiplicity of definitions within EU policy documents and across Member States, and suggest that energy poverty could be defined as: “the difficulty or inability to ensure adequate heating in the dwelling and to have access to other essential energy services at a reasonable price” (EESC, 2011: 1). The second EESC opinion document was published in 2013, and is an own-initiative opinion on coordinated European measures to prevent and combat energy poverty. Here, the EESC reiterated their call for a common general definition of energy poverty, and argued that the EU has no definition or indicator of energy poverty, and the problem is dealt with in a piecemeal fashion.

During this latter policy phase, a new energy efficiency Directive was published (2012/27/EU), which recognised the existence of energy poverty and vulnerable customers, and recommended linking energy efficiency financing to targeted programmes to prevent energy poverty. Overall, energy poverty and vulnerable customers receive limited mentions in the Directive, and descriptions are not provided even though definitions are provided for 45 other key terms.

Arguably the biggest development in this phase is the establishment of the Vulnerable Consumer Working Group (VCWG) in 2012, and publication of their guidance document in 2013. The VCWG was established by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Energy, in collaboration with the Directorate-General for Health and Consumers, to explore the concept of a vulnerable customer, and to support Member State implementation of the Third Energy Package. The VCWG received input from various stakeholders, including academia and industry associations, and represents a critical juncture in EU policy.

Guidance issued by the VCWG (2013) is based on a thorough examination of the drivers of consumer vulnerability in energy markets. However, the VCWG conclude that it is not possible to have a single EU-wide definition of a vulnerable customer, and instead list numerous potential drivers of vulnerability. The advantage of this approach is that it broadens the focus of policy away from the prevailing triad of fuel poverty drivers, namely household income, energy efficiency and energy prices. However, the associated risks are that Member States focus on softer consumer regulations at the expense of structural investments in energy efficiency and housing standards.

The most recent policy document is an opinion published by the CoR in 2014 on the topic of affordable energy, which emphasised the extent of energy poverty across Europe, and called for various measures to alleviate the problem. The opinion document is critical of the European Commission’s inaction to date, stating that:

“the European Commission has so far failed to sufficiently address energy poverty as a significant policy challenge, despite pressure from the European Parliament, European Economic and Social Committee and other stakeholders” (CoR, 2014: 16).

Overall, the CoR argue that an elaboration of the definition of energy poverty is essential in order to promote:

“…recognition of the problem at the political level on the one hand, and to ensure legal certainty for measures to combat energy poverty on the other; such a definition should be flexible in view of the diverse circumstances of the Member States and their regions…” (CoR, 2014: 15).

Concluding discussion

Concerns about fuel poverty were first raised within EU policy documents in 2001, since which time there have been three distinct phases in policy development. Whilst it is evident that formal protection for vulnerable consumers and energy poor households has increased considerably over the 2001 to 2014 timeframe, the loose wording of current Directives allows Member States to absolve themselves of responsibility, and fails to provide comprehensive protection for all households at risk of fuel poverty. This is in spite of the clear support implicit in many European policy and opinion pieces for the EU to go much further in addressing fuel and energy poverty.

The multiplicity of both concepts and definitions of concepts is problematic. However, the EESC note that obfuscation could be resolved by adopting a harmonised broad definition at the European-level, which could then be tailored to national contexts. The European Parliament, EESC and CoR have consistently called for a pan-EU definition of fuel poverty since 2008, stating that the benefits include increased political recognition, policy synergies and policy transfer. This corresponds with the sentiments of academic and advocacy groups that support a broad EU definition of fuel poverty (e.g. Morgan, 2008; EPEE, 2009; Boardman, 2010; European Anti-Poverty Network, 2010; Bouzarovski et al., 2012).

A growing discourse on vulnerable customers has further clouded the debate, since the term has received de facto usage by the European Commission as an alternative to fuel poverty or energy poverty. Here too, history may be repeating itself, since Member States seem – to date –equally unwilling to perform their obligations to define vulnerable groups. On the whole, the decisions taken by the European Commission since 2001 illustrate a consistent pattern of veto, which has circumvented the majority of recommendations made by the European Parliament, EESC and CoR.

Overall, we conclude that the benefits of developing a broad common EU definition of fuel poverty outweigh the potential risks. However, the common definition should avoid being overly prescriptive. Instead, Eurostat should be consulted on ways to improve and expand data collection, and Member States should be encouraged to review fuel poverty in their respective countries, and subsequently develop a detailed national definition that builds on the common EU definition and is appropriate to local contexts.

Harriet Thomson, The Department of Social Policy and Social Work, The University of York, Heslington, York, YO10 5DD, UK. Email: hrt500@york.ac.uk

Anderson, W., White, V. and Finney, A. (2010) “You just have to get by” Coping with low incomes and cold homes. Bristol: Centre for Sustainable Energy.

Bazilian, B., Sagar, A., Detchon, R. and Yumkella, K. (2010) More heat and light. Energy Policy, 38, 5409-5412. CrossRef link

Birol, F. (2007) Energy economics: a place for energy poverty in the agenda? The Energy Journal, 28, 1–6. CrossRef link

Boardman, B. (2010) Fixing Fuel Poverty: Challenges and Solutions. London: Earthscan.

Bouzarovski, S. and Petrova, S. (2015a) The EU Energy Poverty and Vulnerability Agenda: An Emergent Domain of Transnational Action. In: J. Tosun, S. Biesenbender, and K. Schulze, (Eds.) Energy Policy Making in the EU: Building the Agenda. Berlin: Springer: 129-144. CrossRef link

Bouzarovski, S. and Petrova, S. (2015b) A global perspective on domestic energy deprivation: Overcoming the energy poverty–fuel poverty binary. Energy Research & Social Science, 10, 31-40. CrossRef link

Bouzarovski, S., Petrova, S. and Sarlamanov, R. (2012) Energy poverty policies in the EU: A critical perspective. Energy Policy, 49, 76-82. CrossRef link

Brunner, K-M., Spitzer, M. and Christanell, A. (2012) Experiencing fuel poverty. Coping strategies of low- income households in Vienna/Austria. Energy Policy, 49, 53-59. CrossRef link

Buzar, S. (2007) Energy Poverty in Eastern Europe: Hidden Geographies of Deprivation. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Committee of the Regions (CoR) (2014) Opinion of the Committee of the Regions – Affordable Energy for All. Official Journal of the European Union, C 174/15.

Committee of the Regions (CoR) (2008) Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Third legislative package on European electricity and gas markets’. Official Journal of the European Union, C 172/55.

Department of Energy and Climate Change (2013) Fuel Poverty Report – Updated. London: HMSO.

Department of Energy and Climate Change (2010) Fuel Poverty Methodology Handbook. London: HMSO.

Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on energy efficiency, amending Directives 2009/125/EC and 2010/30/EU and repealing Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC. Official Journal of the European Union, L 315/1.

Directive 2009/73/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning common rules for the internal market in natural gas and repealing Directive 2003/55/EC. Official Journal of the European Union, L 211/94.

Directive 2009/72/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 2003/54/EC. Official Journal of the European Union, L 211/55.

Directive 2003/55/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2003 concerning common rules for the internal market in natural gas and repealing Directive 98/30/EC. Official Journal of the European Union, L 176/57.

Directive 2003/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2003 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 96/92/EC. Official Journal of the European Union, L 176/37.

Directive 98/30/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 June 1998 concerning common rules for the internal market in natural gas. Official Journal of the European Union, L 176/57.

Directive 96/92/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 December 1996 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity. Official Journal of the European Union, L 027.

EUR-Lex (n.d.) About EUR-Lex [online]. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/content/welcome/about.html (Accessed: 16/10/14).

European Anti-Poverty Network (2010) EAPN Working Paper on Energy Poverty. Brussels: European Anti-Poverty Network.

European Commission (2010a) Commission Staff Working Paper: An Energy Policy for Consumers. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2010b) Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. The European Platform against Poverty and Social Exclusion: A European Framework for social and territorial cohesion (COM. 16.12.2010). Luxembourg: Office for the Official Publications of the European Communities.

European Commission (2010c) Communication from the Commission Europe 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth (COM. 3.3.2010). Luxembourg: Office for the Official Publications of the European Communities.

European Commission (2008) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament pursuant to the second subparagraph of Article 251(2) of the EC Treaty concerning the common position of the Council on the adoption of a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 2003/54/EC (COM(2008)906 final). Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2007a) Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament: Prospects for the internal gas and electricity market (COM (2006) 841 final). Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2007b) Commission staff working document – Accompanying the legislative package on the internal market for electricity and gas – Impact Assessment [online]. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52007SC1180:EN:HTML (Accessed: 03/2013).

European Commission (2007c) Communication from the Commission to the European Council and the European Parliament: An Energy Policy for Europe (COM (2007) 1 final). Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2007d) Communication from the Commission: Towards a European Charter on the Rights of Energy Consumers (COM (2007)386 final). Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2002) Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament: Energy cooperation with the developing countries (COM (2002) 408 final). Brussels: European Commission.

European Coal and Steel Community Consultative Committee (ECSC) (2001) Opinion of the ECSC consultative Committee on the European climate change programme and emissions trading. Official Journal of the European Communities, (C 170/8).

European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) (2013) Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on ‘For coordinated European measures to prevent and combat energy poverty’ (own-initiative opinion). Official Journal of the European Union, C 341/21.

European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) (2011) Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on ‘Energy poverty in the context of liberalisation and the economic crisis’ (exploratory opinion). Official Journal of the European Union, C 44/53.

European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) (2008a) Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on the Communication from the Commission: Towards a European Charter on the Rights of Energy Consumers. Official Journal of the European Union, C 151/27.

European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) (2008b) Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on the

— ‘Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2003/54/EC concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity’

— ‘Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2003/55/EC concerning common rules for the internal market in natural gas’

— ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing an Agency for the cooperation of energy regulators’

— ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EC) No 1228/2003 on conditions for access to the network for cross-border exchanges in electricity’

— ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EC) No 1775/2005 on conditions for access to the network for cross-border exchanges in natural gas’. Official Journal of the European Union, C 211/23.

European Fuel Poverty and Energy Efficiency Project (EPEE) (2009) Definition and Evaluation of fuel poverty in Belgium, Spain, France, Italy and the United Kingdom. WP2 – Deliverable 7.

European Parliament (2010) Resolution of 15 December 2010 on Revision of the Energy Efficiency Action Plan (2010/2107(INI)). Official Journal of the European Union, C 169 E/66.

European Parliament (2008a) Legislative resolution of 9 July 2008 on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2003/55/EC concerning common rules for the internal market in natural gas. Official Journal of the European Union, C 294 E/142.

European Parliament (2008b) Legislative resolution of 18 June 2008 on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2003/54/EC concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity. Official Journal of the European Union, C 286 E/106.

Greer, S.L. (2008) Choosing paths in European Union health services policy: a political analysis of a critical juncture. Journal of European Social Policy, 18, 219-231. CrossRef link

Hall, P.A. and Taylor, R.C.R (1996) Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44, 5, 936-957. CrossRef link

Healy, J.D. (2003) Excess winter mortality in Europe: a cross country analysis identifying key risk factors. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 784-789. CrossRef link

Healy, J. D. and Clinch, P. (2002) Fuel poverty in Europe: A cross-country analysis using a new composite measure. Environmental Studies Research Series. Dublin: University College Dublin.

Hills, J. (2012) Getting the measure of fuel poverty: Final Report of the Fuel Poverty Review. Report 72. London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion.

Househam, I. and Musatescu, V. (2012) Improving Energy Efficiency in Low-Income Households and Communities in Romania: Fuel Poverty Draft assessment report. Romania: United Nations Development Programme.

Hsieh, H-F. and Shannon, S.E. (2005) Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277-1288. CrossRef link

Liddell, C., Morris, C., Thomson, H. and Guiney, C. (2016, in press) Excess winter deaths in 32 European countries 1980- 2013: a critical review of methods. Journal of Public Health.

Liddell, C. and Guiney, C. (2014) Living in a cold and damp home: frameworks for understanding impacts on mental well-being. Public Health, 26, 1-9.

Liddell, C., Morris, C., McKenzie, S.J.P. and Rae, G. (2012) Measuring and monitoring fuel poverty in the UK: National and regional perspectives. Energy Policy, 49, 27-32. CrossRef link

Liddell, C. and Morris, C. (2010) Fuel poverty and human health: A review of recent evidence. Energy Policy, 38, 2988-2997. CrossRef link

Middlemiss, L. and Gillard, R. (2015) Fuel poverty from the bottom-up: Characterising household energy vulnerability through the lived experience of the fuel poor. Energy Research & Social Science, 6, 146-154. CrossRef link

Moore, R. (2012) Definitions of fuel poverty: Implications for policy. Energy Policy, 49, 19-26. CrossRef link

Moraes, C. (2003) WRITTEN QUESTION E-1789/03 by Claude Moraes (PSE) to the Commission. Official Journal of the European Union, 2004/C 51 E/155.

Morgan, E. (2008) Energy poverty in the EU. Cardiff: Labour European Office.

Office for Social Inclusion (2007) National Action Plan for Social Inclusion 2007–2016. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Pierson, P. (2004) Politics in time: history, institutions, and social analysis. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Plan Bâtiment Grenelle (2009) Groupe de travail Précarité énergétique Rapport [online]. Available at: http://www.plan-batiment.legrenelle-environnement.fr/index.php/actions-du-plan/rts (Accessed: 16/10/14)

Sagar, A.D. (2005) Alleviating energy poverty for the world’s poor. Energy Policy, 33, 1367–1372. CrossRef link

Snell, C., Bevan, M. and Thomson, H. (2015) Justice, fuel poverty and disabled people in England. Energy Research & Social Science, 10, 123–132. CrossRef link

Snell, C. and Thomson, H. (2013) Reconciling fuel poverty and climate change policy under the Coalition government: Green deal or no deal? In: G. Ramia and K. Farnsworth (eds.) Social Policy Review 25: Analysis and debate in social policy. Bristol: The Policy Press. CrossRef link

Strakova, D. (2014) Energy Poverty in Slovakia. Regulatory Review.

Thomson, H. and Snell, C. (2014) Fuel Poverty Measurement in Europe: a Pilot Study [online]. Available at: http://fuelpoverty.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Fuel-Poverty-Measurement-in-Europe-Final-report-v2.pdf (Accessed 7th December 2015).

Thomson, H. and Snell, C. (2013) Quantifying the prevalence of fuel poverty across the European Union. Energy Policy, 52, 563-572. CrossRef link

Thomson, H. and Thomas, S. (2015) Developing empirically supported theories of change for housing investment and health. Social Science & Medicine, 124, 205-214. CrossRef link

Thomson, H. (2011) Qualifying and quantifying fuel poverty across the 27 EU member states (Master’s dissertation). York: University of York.

Tirado Herrero, S. and Ürge-Vorsatz, D. (2012) Trapped in the heat: A post-communist type of fuel poverty. Energy Policy, 49, 60–68. CrossRef link

Ürge-Vorsatz, D. and Tirado Herrero, S. (2012) Building synergies between climate change mitigation and energy poverty alleviation. Energy Policy, 49, 83-90. CrossRef link

Vulnerable Consumer Working Group (2013) Vulnerable Consumer Working Group Guidance Document on Vulnerable Consumers. Brussels: European Commission.

Wallace, H., Pollack, M.A. and Young, A.R. (2010) Institutions, Process, and Analytical Approaches: An Overview. In: H. Wallace, M.A. Pollack, and A.R. Young., (Eds.) Policy-Making in the European Union, 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 3-13.