Abstract

Prior to the Credit Crunch some economists denied the existence of a housing market bubble because the fundamentals supporting inflation were right. Their analysis relied upon assumptions about households as purchasers as the main drivers of the market (transaction volumes and value). The financial crisis and its fallout have shown us that the beliefs and behaviours of other tightly knit groups such as lenders and developers, or more loosely affiliated groups such as landlords, are also crucial to the operation of markets. Weber would have referred to these as “social carriers” in his multi-causal explanations of society. This paper argues that household driven models of “fundamentals” no longer explain the housing market, if they ever did. The current rise of the private landlord and the decade long decline of home-ownership is the beginning of the return of minority ownership of the UK housing stock, a long term change resulting from changed interests and perceptions among the “social carriers” affecting UK housing markets. This has huge implications for almost all aspects of social, welfare and (probably) economic policy.

Introduction

The roots of the current financial crisis (2007/8 onwards) have been subject to extensive discussion and analysis. Harvey (2005), Dumenil and Levy (2011), Engelen et al (2011), Castells et al (2012), consider it an outcome of neo-liberalism while Shiller (2008), Turner (2008), Turner (2012), among many others have a more technical focus on the operations of the finance industry. The consequences have lingered longer than many initially anticipated1 and the crisis has slowly snowballed from problems of solvency in the banking and other financial industries to a crisis affecting nations, currencies, and at the moment even the viability of the European project.

Given the enormity of this crisis, it may seem rather trivial to highlight the gradual decline of home-ownership in the UK, but tenure change will affect economic and welfare policy for decades, and has a momentum derived from current configurations of circumstances that will make it hard to slow or reverse. There is logic to continued home-ownership decline that has yet to be fully explored. Changes to welfare states driven by neo-liberalism (Hemerijk, 2013) have accelerated rather than reversed as the finance industries draw increasing proportions of international wealth to themselves (Dumenil and Levy, 2011). After this crisis there may be no democratically sustainable solution to housing and welfare problems that looks like past policies including expanded home-ownership which was crucial to the vision of a “property owning democracy”.

Weber (1904-05, 1968) sought understanding of complex social change and identified that economy, technology, or other single factors were unlikely to be the true cause of social change. There is no “’ultimate’ point in the chain of causes” (Kalberg, 2005: 45) because any single factor always links to other factors. His multi-causal effects draw on a range of concepts including that of “social carriers”. A recurring theme in his work, Weber explains social carriers in the following way:

In order for a particular type of organized life […] adapted to the uniqueness of modern capitalism to be “selected” (that is, more than others), obviously they must first have originated among – and as a mode of thinking be carried by – groups of persons rather than simply by isolated individuals. (1904-05: 19)

With specific reference to the rise of the modern economy he says:

…on the threshold of the modern epoch, the capitalist entrepreneurs of the commercial aristocracy were by no means exclusively or predominantly the social carriers of that frame of mind here designated as the spirit of capitalism. On the contrary the upwardly mobile strata of the industrial middle classes were far more so. (1904-05: 27)

Thus groups of individuals or organizations can develop ideas and mechanisms for bringing about change that meets their needs or ideals. As Kalberg (2005) explains:

… [Weber’s] sociology characteristically attends to whether powerful and cohesive groupings appear as social carriers, for only then can the influence of regular action range across decades and even centuries. (ibid: 23)

It is the contention of this paper that mortgage lenders, politicians, and a deepening middle class seeing home as an asset (in financial and social terms) were the social carriers that established the regular action that supported the rise of home-ownership over 80 years to 2000. Lenders particularly had stable and low risk approaches to the long term interests of both their assets and their “members”. Even though economic circumstances changed over time the Building Societies “carried” expanding home-ownership practically and culturally, expanding both popular interest in, and the asset value of, the tenure. By 2000 it was the “tenure of choice” for more than the 70 per cent of households enjoying its benefits.

But the interests of some of the social carriers are no longer so wholly vested in owner-occupation. Crucially there were two major changes affecting mortgage lenders during the 1980s. First the deregulation and restructuring of the mortgage market introduced greater competition (Garnett, 2000; Gibb et al., 1999, Boleat, 1986) and saw the start of the decline of building societies as deposit account holders and mortgage lenders (Buckle and Thompson: 100, 105). Second the effects of the financial “big bang” of the 1980s (see Heffernan, 2005) led to the rapid growth of an almost unregulated finance industry and its ‘innovative products’ generating short term profits for management and operatives that contributed to the Global Financial Crisis (Dumenil and Levy, 2011).

Even after the crisis there remains greater emphasis on short-term shareholder and staff/management interests than in the long term interests of home-owners. Also, as this paper will show, traditional homeowners are no longer the key to sustaining the value of the housing assets that mortgages are secured against. In fact the bubble before the credit crunch took house prices well beyond the means of traditional owner-occupiers at the lower end of the market and these have been replaced by landlords – a newly expanding rentier class owning more than one dwelling (Rugg and Rhodes, 2008). Landlords take on some of the risks associated with sustaining banks’ asset values as will be shown below. We have yet to fully incorporate this change into our thinking about housing policy and related welfare issues.

Beginning with a brief critique of the traditional “fundamentals” approach of economic models of the UK housing market this paper will move towards a multi-causal explanation of housing market change. While I do not suggest that this change will range across centuries, we are clearly moving into the second decade of a major restructuring of housing tenure in the UK and far from it being an anomaly there is a demonstrable logic to the continuation of this trend. Lenders, estate and letting agents, landlords (as a loosely coherent grouping), developers, and government itself (even though it claims to still promote home-ownership through some policies) are acting as the “social carriers” of this fundamental change.

The key argument here is that the correlations associated with traditional economic observations of the housing market (transaction volumes and price movements) during the expansion of owner-occupation no longer apply. The ‘fundamentals’ of this correlation were factors affecting household level consumption such as incomes, household formation etc. (see below) and were the basis of the models of the housing market that so spectacularly failed to understand that market prior to the credit crunch. While house prices in the UK have been sustained, the traditionally understood housing market, based on expanding home ownership driven by first-time-buyer (FTB) acquisitions at the base of the pyramid, has been undermined by the changing imperatives of the “social carriers”. The resultant tenure restructuring is substantial and long term.

Background: Bubbles and fundamentals in the housing market

Theoretical models of the housing market assume individual households to be the purchasers of new and second hand housing (purchasing for their own use as occupiers). Models therefore identify factors that affect, and generate, households, and sustain their aspirations to ownership, as being the ‘fundamentals’ that drive the market (discussed in more detail below). In a market where there is under-supply (as there has been in the UK for three decades) this model commonly predicts continuing asset price inflation and the assumption of endless asset price inflation helped develop and sustain the recent bubble in an extended virtuous circle.

Prior to the global financial crisis residential property asset inflation converged across the globe in an unprecedented way (Shiller, 2005). Dumenil and Levy (2011) argue that the recovery of the financial industries from the dot com bubble of the 1990s was “achieved thanks to the housing boom, itself fuelled by the explosion in households’ indebtedness” (p. 173). The ‘wealth’ generated in one bubble was transferred to a different asset, generating a new asset bubble in its turn, pumping liquidity into generally inflexible/illiquid financial holdings in property. Essentially the market was driven by externally generated liquidity seeking a more secure base rather than any household level fundamentals. Spreading the over-inflation risk across millions of households gave investors and financial modellers a sense of security and sustained further speculative activity where lenders tried to find new ways to direct cash flows into residential property.

Knoop (2008) explains that an asset bubble:

refers to a market in which the prices of assets rise above that which can be justified by the asset’s fundamentals, which includes the characteristics of the asset itself – the expected return and the terms of the financial instrument – as well as the characteristics of the borrower – their credit history, their net worth, and their cash flows. (Ibid, 2008: 164)

Fundamentals should therefore be the factors that determine the baseline of the ‘real’ value of the asset. However the housing market found itself in a situation where inflation itself became a fundamental that drove increased confidence.

A bubble is also “defined in terms of people’s thinking: their expectations about future price increases, their theories about the risk of falling prices, and their worries about being priced out of the housing market in the future if they do not buy” (Case and Shiller, 2003: 301). The latter definition relates to levels of confidence, the former to evidence as to whether that confidence is justified. Economic analysis of the “fundamentals” of the housing market is intended to provide that evidence.

Before the financial crisis the Governor of the Bank of England said:

House prices are high relative to the measures that help to put them into context – average earnings and incomes. By some measures they are remarkably high. (Mervyn King, in Elliott, 2006)

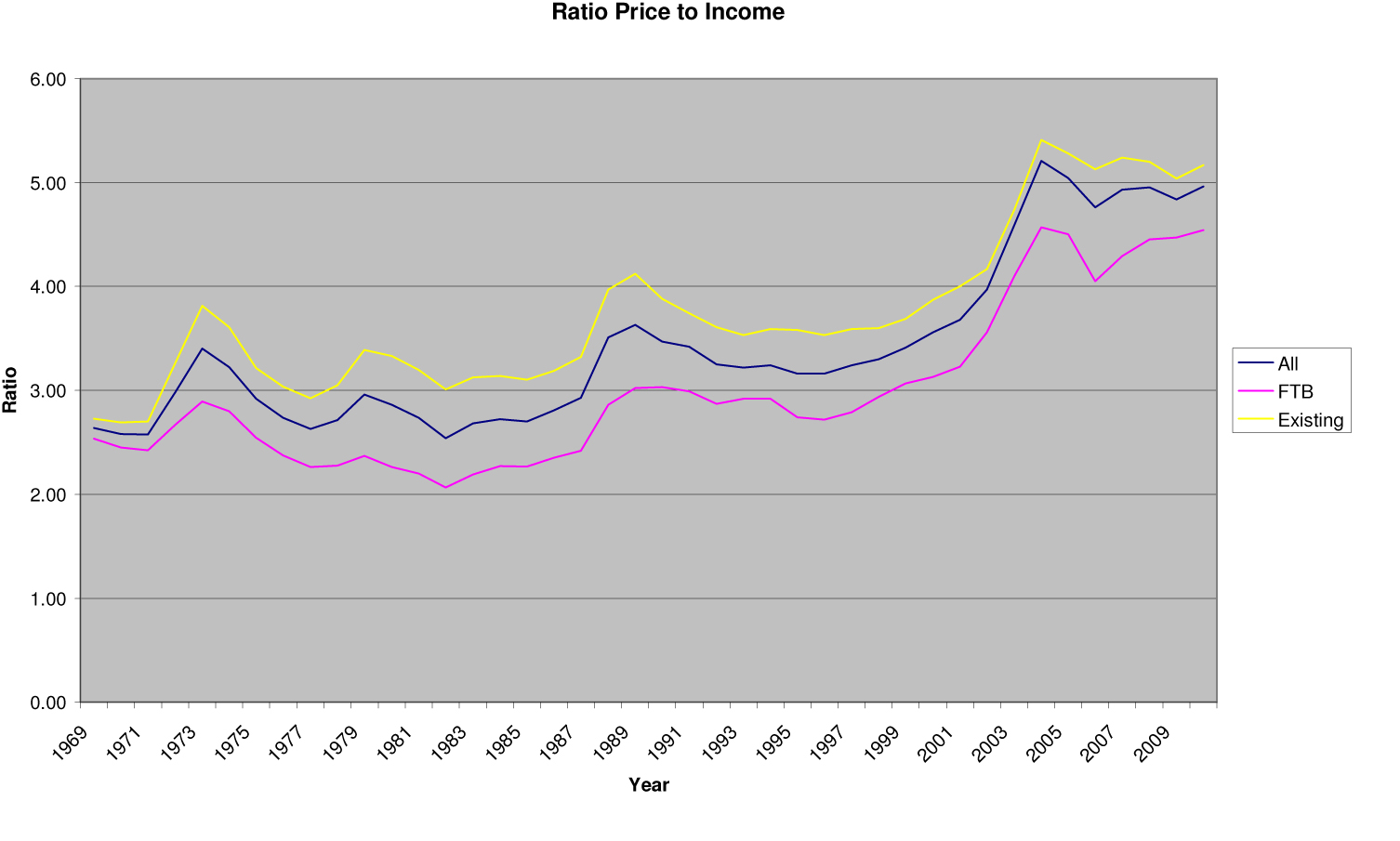

King’s fundamentals as determinants of the ‘real’ value of houses in the UK were average earnings and incomes compared with the average price of houses. This ratio is traditionally seen as healthy when it stands at around 3:1 which it did for many years. Figure 1 shows the 3:1 price to income ratio from 1970 (with fluctuations) over three decades but then rising markedly from around 2002.

Averaging house prices and incomes across the UK (or any large geographical area) tends to damp down the often more extreme local variations. CLG Table 577 (accessed 2/08/12) uses district level median price to median income ratios which reached over 10:1 in several areas and 12:1 in some London Districts. Neighbourhood level variations can be even greater.

Despite this divergence from supposed norms or limits the economic analyses failed to predict problems. The National Housing and Planning Advisory Unit (NHPAU) study of 2008 summarized recent research (e.g. Meen, 2006; Muellbauer and Murphy, 1997; HM Treasury, 1992; Drake, 1993) and stated that:

The econometric work shows that a large proportion of the variance in house prices over time can be explained by fundamental economic and demographic factors. For instance models of the UK housing market show that prices change in relation to real incomes, the number of households, population trends, expectations, credit availability and the cost of borrowing. (NHPAU 2008: 8)

In another study, Cameron et al (2006) explain that:

Our model captures long run fundamentals such as the effect of income, population, age composition, the housing stock, and interest rates on the long-run level of real house prices. It also builds in the effect of house price dynamics, including transmission from leading or adjacent regions on other regions. In the UK, the leading region is London, and the “ripple effect” of changes there impacting on other regions, first on adjacent ones, is a notable feature in the UK. (Ibid: 23)

The NHPAU study of fundamentals concluded that private rented sector (PRS) growth through BTL lending had only added marginally to house price inflation. Cameron et al’s analysis indicated “No evidence for a recent bubble”. The housing market was working normally.

On the other hand the OECD (2005) had, a year earlier, stated that the models “uniformly point to overvaluation in the United Kingdom, Ireland and Spain” (Ibid: 127) and in the case of the UK this overvaluation could be as much as 30 per cent. The OECD used a wider range of criteria for their analysis, noting that investor rather than consumer activity characterized these housing markets. On p.138 they specifically cite investment activity as a potential driver:

Other factors, however, may just raise the price of housing. Buy-to-let markets, which have grown substantially over the past several years in the countries for which data are available (United States, United Kingdom, Australia and Ireland), are one example. […] These markets are, however, dominated by small, first-time investors and their effect on the housing market is not well understood.

Interestingly Cameron et al (2006) had noted above the “ripple effect” that refers to the propensity of London to lead/drive wider UK price rises. London is the largest speculator driven housing market in the UK with the lowest level of home-ownership of all the regions. So the region that ‘leads’ the UK housing market in analysis based on “fundamentals” relating to households is the one already most disconnected from household level demand.

PRS expansion

Although it is often assumed that the Private Rented Sector (PRS) adds to housing supply landlords generally do not build new houses. Instead they buy them from the same pool of housing stock (new and existing) that family households buy them from. As landlords purchase more, other households are able to purchase less in a fixed supply market and the impact of this can be seen in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1: Changing proportions of housing stock in private tenures, Great Britain

|

Year |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

|

Owner Occupiers % |

69.4 |

69.6 |

68.8 |

69.2 |

69.2 |

68.4 |

68.0 |

67.2 |

66.3 |

65.4 |

|

Privately rented % |

9.7 |

9.9 |

11.3 |

11.4 |

12.0 |

12.9 |

13.6 |

14.7 |

15.7 |

16.6 |

Source: Wilcox and Pawson: UK Housing Review 2011/12

Table 2: Volume of annual change in private tenure housing stock, Great Britain

|

Year |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

|

Decline in Home Ownership |

-41,000 |

-120,000 |

-144,000 |

|

Growth of PRS |

+304,000 |

+293,000 |

+271,000 |

Source: Calculated from Wilcox and Pawson: UK Housing Review 2011/12

While annual transaction volumes in the UK have fallen from 1.6m/year to around 0.85m (Wilcox and Pawson, 2012) the level of home-ownership has fallen further reverting to its position a decade ago in terms of numbers and twenty years ago as a percentage of total stock (Ibid, Table 17c). Since 2008 the rate of decline is 1 per cent/year and even without the apparent accelerating trend indicated in Table 2, a decade of decline running simply at the 2010 rate would reduce home-ownership by over 1.4 million dwellings by 2020; almost a complete reversal of the effects of the Right to Buy as one of the biggest single policy boosts to expanding home ownership in the twentieth century (King, 2008, Heywood, 2011). In fact Right to Buy stock features significantly in PRS expansion (Sprigings and Smith, 2012).

Changed fundamentals for lenders: Landlords or homeowners?

As recently as the mid 1990s First Time Buyers (FTBs) made up 54 per cent of the new mortgage market in the UK with Buy-to-Let mortgages at almost zero as they were only initiated in the mid 1990s (CLG Live Table 513). The recent peak of lending to FTBs was in 1999 with 592,000 loans (comprising 47 per cent of house purchase mortgage loans) falling to 179,000 loans (34 per cent of house purchase mortgage loans) by 2010 (Wilcox and Pawson, 2012). If the estimates of PRS acquisition activity above are anywhere near correct, then PRS acquisition in the market seems to occur significantly at the expense of FTBs. This would be supported by the combined evidence that successful FTBs are now having to buy higher value home types (the proportion of terraced housing and flats they buy has fallen) and to find higher deposits often, as is now commonly reported, with help from parents (who may be releasing equity from their own homes for this purpose). Of course younger households with more flexible lifestyles are often cited (e.g. Pattison et al., 2010: 35; Ball, 2006) as those ‘choosing’ to rent privately for a variety of reasons which is very lucky for the growing number of landlords. Pattison et al (2010) also acknowledge that the PRS may expand as a result of households not having the choice to enter other tenures; real choices can be hard to specify as they are not always made in the conditions of our own choosing.

Demographic fundamentals referred to above assume demand from new households but there is further evidence of the difficulty for younger households to enter the market. For example, in 2002 fewer than 50 per cent of mortgages went to households earning over £30k/year (CLG Table 538) but by 2011 this has risen to 77 per cent of mortgages (ibid) and £30k/year is still well above average salaries or new/young household incomes. The National Housing Federation (NHF, 2012) analysis shows a 94 per cent average increase in house prices in England between 2001 and 2011 (to £236,500) while average salaries increased 29 per cent (to £21,300). So lender priorities in terms of their more desired borrowers are significantly shifting the home-ownership market (and therefore overall market activity) away from younger, lower income, and FTB households.

As the number of high income households moving to high value property is insufficient to sustain mortgage lending the drop in mortgage availability since 2006 is dramatic. CLG Table 544 shows the number of mortgage approvals falling from 1.13m in 2006 to 531,000 in 2010. Assuming that some of the other fundamentals remained (there were households forming, migrants arriving, people wishing to move, interest rates low, etc.) the effects of the lenders decision to reduce access to mortgages on lower value stock is clear. The same CLG Table (544) also shows a long term decline in the value of the loan as a proportion of purchase price. In 2006 the average loan was 67.5 per cent of the price, by 2010 it has fallen to 60.6 per cent (this ratio does fluctuate over longer time periods) so higher deposits are needed. The NHF calculates the rise in deposits as being 386 per cent “so the deposit needed for a typical 75 per cent mortgage leapt to £59,129, almost three years salary.” (NHF, 2012). The 3:1 ratio now relates to the deposit rather than the mortgage value.

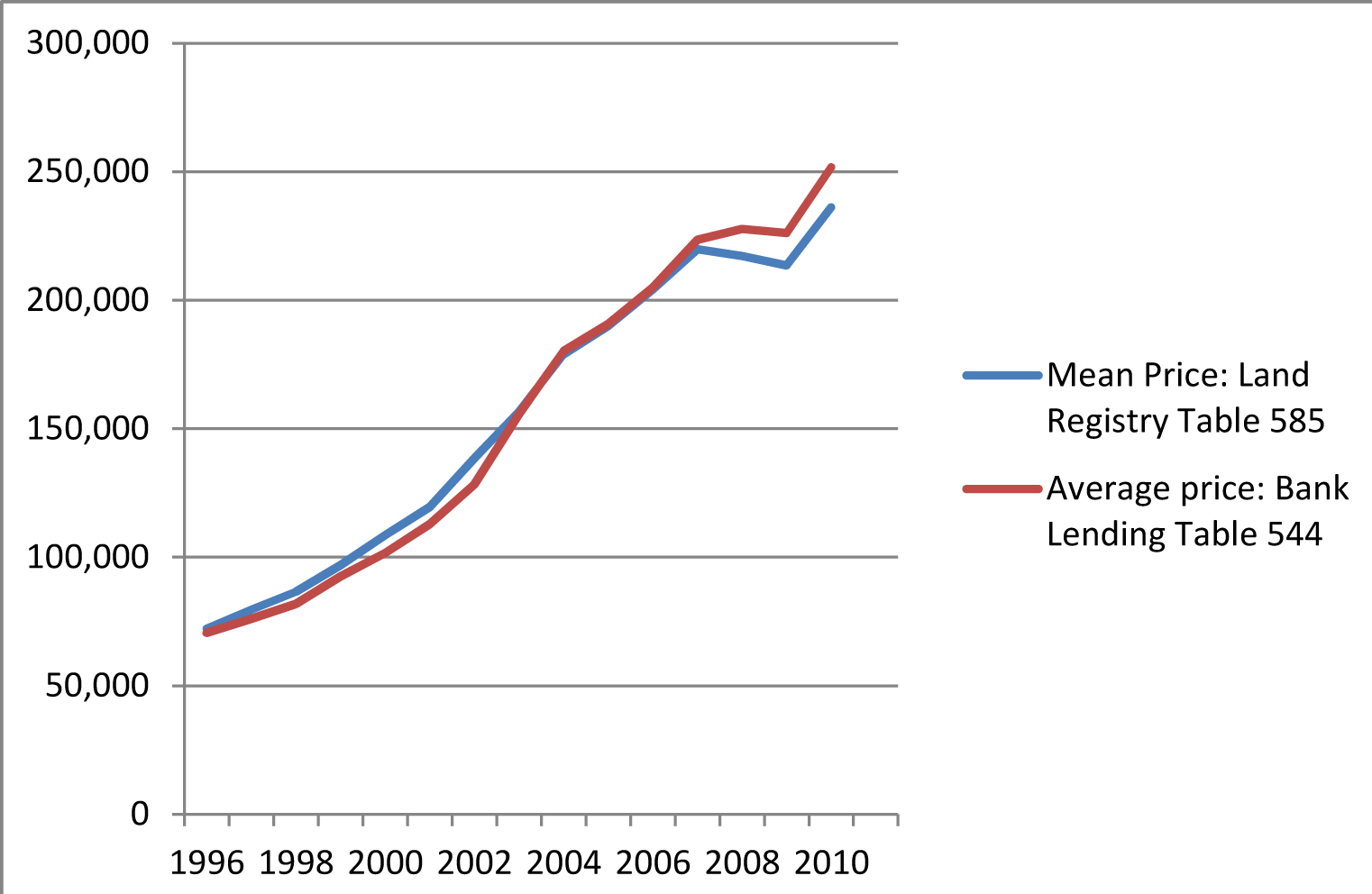

Many of the changes detailed above are designed to protect the interests of lenders in the changed financial climate. One of the key risks to lenders at the moment is the risk of falling asset values – recall the OECD talked of a pre-crash overvaluation of perhaps 30 per cent. The effect of lending restrictions on price indicators is interesting, especially when we consider the simple average prices rather than weighted averages which are created to remove the effect of “exceptional” areas such as London. Below I will use simple averages to reveal some overall changes in the market.

Far from there being a price correction as there has been in the US (Financial Times 10/09/2012 reports that “The US housing market has fallen more than 30 per cent in the past 6 years”), CLG data (Live Table 504) indicates that average house prices rose until the third quarter of 2008 when there was a slight slump followed by recovery. In 2006 the average price of all sales was £199k, by the third quarter of 2008 this was £233k, and at Q3 2011 the figure stands at £254k.

Figure 2 compares house price trends as indicated by the average value of property on which Banks or Building Societies lent for house purchase (red line) and the average price from Land Registry transaction records of all transactions (which will include cash sales). This shows the continued rise in average prices using both measures but also has the interesting feature that prior to the financial crisis the average value of houses on which lenders lent was lower than the average price of all sales. These values merged towards the credit crunch but have subsequently reversed. The average price on which lenders lend is now higher than the average price derived from all sales transactions. There are two simple interpretations of this, both with an element of truth. Lenders now only lending on higher value homes allows them to advise the market of higher average house values thus protecting their exposure to the market by shaping it through their own lending behaviour. Secondly, cash buyers (including landlords) are buying the lower value stock and slightly reducing the overall average price in Land Registry data. Thus increasing average prices are sustained within the context of historically low sales volumes.

Another effect of changing lending criteria and therefore of lending patterns, is the regional impact of loan restrictions. Sales volumes have fallen throughout the UK but at varying rates. The cheaper areas have seen greater falls in transactions than the higher value areas. In Inner London the fall in sales volumes since the 2006 peak is only 43 per cent while in the NE and the NW of England the fall is 57 per cent and 58 per cent respectively. Even this regional average masks bigger local falls. In the NW for example, the fall in transaction volumes in Burnley is 70 per cent (CLG Table 588). The irony of this outcome is that where housing is most affordable are exactly the locations where lenders are least likely to help households buy it.

The final word on this shifting lending priority should go to the Council of Mortgage Lenders (CML) whose director general Paul Smee says:

Even though buy-to-let lending is running at only around a third of its peak levels, the sector is continuing its gradual expansion. It has become an important part of the overall landscape of housing provision in the UK. (CML report on BTL lending May 2012 p2)

So anyone attempting to understand or model the housing market of the past ten years needs to be able to factor in fundamentals that relate not only to owner occupiers and aspiring owner occupiers, but also the very different fundamentals pertinent to lenders, developers, landlords and aspiring landlords. Islam (2013) points out that the rise in total mortgage lending in 2012 (as part of the Bank of England Funding for lending scheme) was entirely due to increases in BTL lending.

One of the intangible impacts of the introduction of BTL was cultural in that it helped legitimize landlord acquisition as an investment activity, promoted rentier rather than productive economic activity and, as an unregulated form of lending with few restrictions in the boom years, it helped to accelerate property asset gains. Such cultural effects are hard to take account of as fundamentals in econometric modelling as the OECD study of 2005 indicated.

Changing fundamentals and transferring risks

The question remains as to why lenders would want to expand their exposure to the private rental business which, as we hear regularly, is plagued by non-paying tenants who destroy property and abscond at the drop of a hat?2 In some ways lenders have little choice as they are now trapped with asset books full of over-valued assets when considered against traditional financial fundamentals (OECD 2005). So one of the key aspects of this crisis for the mortgage lenders, has become the continual management of the risk of declining asset value and the threat of household default like that which has helped to undermine the sub-prime mortgage market in the USA. A replication of this in the UK, throwing tens of thousands of lower value stock onto a ‘distress sales’ market, would have the effect of lowering transaction prices and therefore the values in lenders asset books.

One of the things lenders have learnt from the rise in the BTL supported PRS in this financial crisis is that landlords are generally a safe bet and play a multiple role in securing asset value through continued acquisition activity, and income streams on mortgage payments through risk transfer. Because rental yields continue to rise due to supply shortage landlords are happy to continue purchasing at current prices so they help to sustain asset values. Landlords who have been in the market for some time are often also cash rich so finding a 30 per cent to 40 per cent deposit is not the problem for them as it is for households. The landlord deposit protects lenders from a 30 per cent to 40 per cent fall in prices/values should that come to pass as the OECD implied.

Landlords also protect lenders from the household level effects of recession and default on housing payments. In a recession exacerbated by government policies creating reduced household income (public sector redundancies, reduced full-time working, reduced capital investment projects, benefit cuts to working households etc.) there are clearly increased risks in lending to the expanding range of financially vulnerable households. Lenders responses in restricting lending have been illustrated above and there is no reason to anticipate more generous lending terms and volumes until wages catch up with prices, something that is not going to happen soon (NHF 2012). Lenders also have to show forebearance on increased rates of mortgage arrears so as not to place volumes of repossessed stock on the market with a risk of lowering prices.

In contrast to homeowners BTL landlords are performing well in terms of repayments. Lenders were initially cautious about renewing support for unregulated BTL lending that had found them in markets they had often entered unknowingly by selling BTL mortgages through brokers and not tracking the nature and location of stock being taken onto to their asset books. Exposure to over-valued city centre markets was enormous (Financial Times, 2008). However BTL defaults have remained at low levels and the CML report of May 2012 states that:

In terms of loan performance, the number of buy-to-let mortgages in arrears fell a little in the first quarter of 2012, and the arrears rate on buy-to-let mortgages continues to be lower than in the owner-occupied sector. At the end of the first quarter, around 1.7% of buy-to-let mortgages were in arrears of more than three months (including cases where a receiver of rent has been appointed), compared with around 2% of owner-occupier mortgages. (CML report on BTL lending May 2012 p.1)

Many tenant households are now paying high proportions of their income in order to service their landlord’s BTL loans, but the immediate risk of non-payment arising from benefit cuts, job loss, or reduced working hours, lies with the landlord. In this way the landlord is placed between the lender and the economically vulnerable household. The advantage of this is that since government removed any security or protection for tenants in newly rented property in 1988, landlords can respond easily and quickly to non-payment through eviction and can replace the non-paying tenant with another tenant who may even be able to afford a higher rent if only for the current six month employment contract. In this way the lenders’ interest in the property is protected far better than it would be if they had a direct relationship with an occupant in insecure and/or low paid employment. Landlords often also have another asset that could be used in case of default, either their own home or other properties in their portfolios.

Local Housing Allowance changes are intended to drive down high PRS rents supported through state spending but these changes have yet to have an impact and evidence from pilots and landlord interviews indicates probable inconsistencies in their responses. For example a study in South Yorkshire noted “the new LHA arrangements prompted several specific observations by landlords in terms of effects and impacts” and noted several responses including “avoiding lettings where LHA is involved, increasing rents above LHA levels to recover losses and cover cost increases (more rent collection etc), and attempting to re-negotiate direct payments without the initial rent loss” (ECOTEC, 2009). In the long term it may be that landlords again find ways to insulate lenders from potentially risky welfare cuts.

Landlords also have more than one way to raise rents and secure the mortgage repayment. In some of the interviews conducted in recent research landlords have expressed the intention of responding to government benefit cuts by sub-dividing property (for example, Nevin-Leather et al, 2011). One of the positive and noteworthy features of the initial expansion of the PRS from the mid 1990s was the decline of bedsitland. However the incentives are now in place for its rapid return, especially in poorer areas, as government drives down living standards in order to encourage people into low paid, insecure work and smaller living space. Weber’s “social carriers” are here acting in concert to effect major change in housing standards and expectations as well as the housing market itself.

Conclusions

The trend away from home-ownership, sustained for over a decade, has been outlined above. So have the changes to the fundamentals of the traditional housing market arising from new priorities and risk assessments among the relevant “social carriers”, primarily lenders, whose low risk approach for a century helped to create and sustain a culture promoting home-ownership. Lenders are not the only “social carriers” however, their interests intersect and interact with those of the new rentier class of landlords, professional letting and sales agents, and the policymakers keen to create greater insecurity for households; all these promote the new culture that generates PRS growth. Greater instability in the home-ownership market, which takes a variety of forms, reduces its appeal to young households but high costs needed to protect asset values and changed lending priorities also reduce access for FTBs. This generates a market for rental at the same time as the attraction of landlordism and acquisition capacities of landlords expand. The impacts have been demonstrated above.

It may now be worth reflecting briefly on some of the major aspects of the current market that would have to change soon for the trend to reverse. For home ownership to revive a wide range of current housing market conditions will need to change:

- In government policy the needs of households would have to be brought more to the fore compared to the needs and interests of lenders. A £400m mortgage guarantee scheme pales in its effects alongside £20bn annual BTL lending plus other PRS investment.

- The price/value of houses would need to “correct” dramatically to within the range determined by traditional fundamentals including household incomes. Or household incomes would need to rise rapidly to “correct” to current house prices and make housing accessible to lower income households and FTBs with small deposits again.

- FTBs would need to be confident that entering the current market did not expose them to repossession through job loss or negative equity through price falls in order to encourage them back into the market.

- Lenders would need to be able to absorb the fall in asset prices point two would require. This may imply a further bailout to prevent another round of bankruptcies. Or lenders would need to be confident that wages were permanent and secure in order to protect them against default and price fall risks in the medium term. Negative equity for borrowers is not a problem for lenders as long as mortgage payments are made. Several of the above would probably need to occur simultaneously in order for lenders to increase household lending again to lubricate the owner-occupation market.

For the PRS to stabilize or decline:

- Landlords would need to be able to find a more lucrative location for their investments and to be able to find this quickly (which implies a level of liquidity and movement in the housing market we are not experiencing, and stability of yields in other investment sectors that currently remain volatile). In the current market some landlords may also be trapped.

- Rents would need to fall in order to make landlord yields less attractive compared to other investment opportunities.

- Landlords exiting the market would need to sell to households rather than other landlords/investors.

None of these seem very likely in isolation let alone in the range of combinations that would be necessary for home ownership to begin expanding again.

There are now around 3m landlords3 in the UK owning more housing than social landlords. Their continued expansion is being promoted by a variety of factors discussed above, but also by the very success that the sector is showing in its ability to weather the effects of recession. One of the intangible effects of BTL mortgages was their support for a changing culture that favours rentier income over other forms of economic productivity. This has been sustained by government through a high yield, low risk regulatory and investment framework. While landlords expand their interests and more wealthy households become landlords, fewer newly forming households will be able to access home-ownership and its long term decline will continue. This may not be a bad thing in itself but while policy makers and politicians fail to recognize the long -term nature of this trend of expanding unregulated rented housing supply, there will be only limited discussion of the type and nature of PRS we want to have in the UK and even less thought given to how this might be created.

It is also the case that because household wealth has been so determined by housing wealth over the past 40 years, we now need to consider what social changes will be brought about by home-ownership becoming again a minority tenure. There are implications for consumption in a consumer society (Sprigings and Craven forthcoming); for household formation and secure/stable family life; for welfare in old age and other factors touched on by Heywood (2011). Also the ideal of a “property owning democracy” engages many favourite political assumptions about community creation, stakeholding in society, and likely political allegiance deriving from majority and expanding home-ownership. This may change but the indicators outlined above are that the “social carriers” that promoted home-ownership are now taking us in another direction.

In the words of Engelen et al (2012: 27) the financial crisis “… is a debacle because this defeat is not easily reversible, avoidable, nor fixable”. Heywood (2011) actually suggests politicians are “in denial”. All of which supports Haldane’s conclusion that “the scars from the current crisis seem likely to be felt for a generation” (2010: 87). Whether declining owner-occupation is a scar is another debate but certainly it is likely to be one of the key effects of the continuing crisis and the unregulated PRS as a policy problem will grow as the sector grows through the coming decades.

1 See for example The Deputy Prime Minister, Nick Clegg, on 29th August 2012 saying “What people once thought might have been a short sharp economic battle, a short sharp recession, is clearly turning into a longer term process…” (Guardian 29/8/2012 p1). This would imply that this was the understanding of government and its advisors.

2 Local and national press gives regular coverage to this problem (e.g. Grimsby Telegraph 2013, Middleton 2009, and Lunn 2012) but landlords also highlight the issue through their own campaign, lobby and newsgroups (e.g. Propertyquotedirect.co.uk 2012; Landlordreferencing.co.uk). Landlords also regularly refer to these issues in research interviews with the author (e.g. Hickman et al 2007 and 2008; ECOTEC 2006; and others).

3 The Tax Justice Network report “About 1 million private landlords did not declare any revenue in the past tax year, compared with 1.9 million who did, according to the Exaro investigative website” (http://taxreturnservice.co.uk/one-in-three-buy-to-let-landlords-is-dodging-tax/).

I’d like to thank the referee for their detailed comments on focus and structure which I hope has led to an improved paper, and also the editors for their support and patience.

Nigel Sprigings, Urban Studies, University of Glasgow, 25-29 Bute Gardens, Glasgow G12 8RS. Email: nigel.sprigings@glasgow.ac.uk

Ball, M. (2006) Buy-to-Let: The Revolution 10 Years On – Assessment and Prospects. Amersham: Association of Residential Letting Agents.

Boleat, M. (1986) The Building Society Industry. 2nd edition. London: Allen and Unwin.

Buckle, M. and Thompson, J. (2004) The UK financial system: Theory and practice. 4th Edition. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Cameron, G., Muellbauer, J., and Murphy, A. (2006) Was there a British House Price Bubble? Evidence from a Regional Panel.

Case, K.E. and Shiller, R.J. (2003) Is there a Bubble in the Housing Market. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2003, 2, 299-342. CrossRef link

Castells, M., Caraca, J. and Cardoso, G. eds. (2012) Aftermath: The Cultures of the Economic Crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

CLG (2013) Communities and Local Government Live Tables available on-line and accessed various dates 2012/13.

Council of Mortgage Lenders (CML) On-line statistics and quarterly reports. http://www.cml.org.uk/cml/statistics

Drake, L. (1993) Modelling UK house prices using cointegration: an application of the Johansen technique. Applied Economics, 25, 1225-1228. CrossRef link

Dumenil, G. and Levy, D. (2011) The Crisis of Neoliberalism. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press.

ECOTEC and Sprigings, N. (2006) Private Rented Sector Study. Stoke-on-Trent City Council. On line: www.stoke.gov.uk/ccm/content/hcp/housing_misc/private-rented-sectorresearch-en

ECOTEC and Sprigings, N. (2009) Research into the private rented sector in South Yorkshire: A report for Transform South Yorkshire. Sheffield: Transform South Yorkshire.

Elliott, L. (2006) Bank of England governor rules out new housing boom. Guardian, 11th May.

Engelen, E., Erturk, I., Froud, J., Johal, S., Leaver, A., Moran, M., Nilsson, A. and Williams, K. (2012) After the Great Complacence: Financial Crisis and the Politics of Reform. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Financial Times (21/04/08) UK Housing: areas to watch. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/b23d02dc-0d5e-11dd-b90a-0000779fd2ac.html#axzz25PsOGk2j

Garnett, D. (2000) Housing Finance. Coventry: Chartered Institute of Housing.

Gibb, K., Munro, M. and Satsangi, M. (1999) Housing Finance in the UK: An Introduction. London: Macmillan.

Grimsby Telegraph (2013) Landlord’s fury at ‘drugs filth’ left by bad tenants at house in Grimsby’s Buller Street. Monday 18 February.

HM Treasury (1992) HM Treasury Macroeconomic Model Documentation, December 1992.

Haldane, A. (2010) What is the Contribution of the Financial Sector: Miracle or Mirage? In: Turner, A. et al (eds) The Future of Finance. London: LSE.

Harvey, D. (2005) A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heffernan, S. (2005) Modern Banking. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

Hemerijck, A. (2013) Changing Welfare States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heywood, A. (2011) The End of the Affair: implications of declining homeownership. London: The Smith Institute.

Hickman, P., Sprigings, N., Whittle, S. and Cole, I. (2007) Gateway Private Rented Sector Study: Final Report. Sheffield: CRESR.

Hickman, P., Sprigings, N., McColough, E. and Cole, I. (2008) The Private Rented Sector in West Yorkshire. Bradford: West Yorkshire Housing Partnership.

Islam, F. (2013) The Bank of England funding for landlords scheme. Channel 4. http://blogs.channel4.com/faisal-islam-on-economics/the-bank-of-england-funding-for-landlords-scheme/17880 Accessed 12/03/2013.

Kalberg, S. (ed.) (2005) Max Weber: Readings and Commentary on Modernity. Oxford: Blackwell. CrossRef link

King, P. (2010) Housing Policy Transformed: The right to buy and the desire to own. Bristol: Policy Press.

Knoop, T.A. (2008) Modern Financial Macroeconomics: Panics, Crashes and Crises. Oxford: Blackwell.

Landlordreferencing.co.uk (2013) Tenant alert areas. Accessed 3/05/2013.

Lunn, E. (2012) Tenants and Landlords: now you can air your grievances online. Guardian Friday 9th March.

Martin, R.F. (2008) Housing Market Risks in the United Kingdom. USA: Federal Reserve Board.

Meen, G (2006) ‘Ten new propositions in UK housing macroeconomics: An overview of the first years of the century’ conference paper, ENHR conference “Housing in an expanding Europe: Theory, policy, participation and implementation”, Ljubljana, Slovenia, July 2006.

Middleton, C. (2009) Bad Tenants? Meet the enforcer. Telegraph, 13 May 2009.

Muellbauer, J. and Murphy, A. (1997) Booms and Busts in the UK Housing Market. Economic Journal, 107, 1720-46. CrossRef link

National Housing Federation (2012) House prices rise three times as much as incomes over ten years. http://www.housing.org.uk/media/news/house_prices_rise_three_times.aspx. Accessed 17/08/12)

National Housing and Planning Advice Unit (2008) Buy to Let lending and the impact on UK house prices: a technical report. London: National Housing and Planning Advice Unit.

Nevin Leather Associates and Sprigings, N. (2011) The Private Rented Sector in Cheshire West and Chester. Chester: Cheshire West and Chester Council.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2005) Recent House-Price Development: The Role of Fundamentals. OECD Economic Outlook, 2005, 2. New York: OECD.

Pattison, B., Diacon, D., and Vine, J. (2010) Tenure Trends in the UK Housing System: Will the private rented sector continue to grow? Leicestershire: Building and Social Housing Foundation.

Propertyquotedirect.co.uk (2012) Property Damage posted 11 July 2012. Accessed 3/05/2013.

Rugg, J. and Rhodes, D. (2008) The Private Rented Sector: Its contribution and potential. London: Department of Communities and Local Government. Available at: http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/chp/publications/PDF/prsreviewweb.pdf

Shiller, R.J. (2005 2nd edition) Irrational Exuberance. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Shiller, R.J. (2008) The Subprime Solution: How Today’s Global Financial Crisis Happened and What to Do about It. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Sprigings, N. and Smith, D. (2012) Unintended consequences: Local Housing Allowance meets the Right to Buy. People, Place and Policy Online, 6, 2, 58-75.

Turner, A. (2012) Economics After the Crisis: Objectives and Means. Cambridge: Mass. The MIT Press.

Turner, G. (2008) The Credit Crunch: Housing Bubbles, Globalisation and the Worldwide Economic Crisis. London: Pluto Press.

Weber, M. (1904-05) The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Stephen Kalberg 2002. Oxford: Blackwell. CrossRef link

Weber, M. (1968) Economy and Society, eds G Roth and C Wittich. New York: Bedminster Press.

Wilcox, S. and Pawson, H. (2012) UK Housing Review. York: CIH/Savills/University of York/Herriot Watt University.